|

Amyntas III – Grandfather of

Alexander III the Great

Macedonian King: 389-383

and 381-369 B.C.

Bronze 16mm (3.28 grams) Struck circa 389-369 B.C.

Reference: Sear 1512; B.M.C. 5. 17-22

Head of young Hercules right, wearing lion’s skin. Countermark.

AMYNTA above eagle standing right, wings closed, devouring serpent held in

talons.

Martin Price, in ‘Coins of the Macedonians’ (p.21), makes the interesting

suggestion that this type belongs to the reign of the infant Amyntas IV (359-357

B.C.), for whom Philip II was regent. This can scarcely be considered proven,

however, and the style of the coins seems to be more akin to the issues of the

early part

of the 4th Cent. B.C.

A great-grandson of Alexander I, Amyntas dethroned the usurper

Pausanias in 389 B.C. He was temporarily expelled from his Kingdom by the

Illyrians in 383, but returned two years later with Spartan assistance.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Serpents

and snakes play a role in many of the world’s myths and legends. Sometimes these

mythic beasts appear as ordinary snakes. At other times, they take on magical or

monstrous forms. Serpents and snakes have long been associated with good as well

as with evil, representing both life and death, creation and destruction.

Serpents and Snakes as Symbols. In religion, mythology, and

literature, serpents and snakes often stand for fertility or a creative life

force—partly because the creatures can be seen as symbols of the male sex organ.

They have also been associated with water and earth because many kinds of snakes

live in the water or in holes in the ground. The ancient Chinese connected

serpents with life-giving rain. Traditional beliefs in Australia, India, North

America, and Africa have linked snakes with rainbows, which in turn are often

related to rain and fertility.

As snakes grow, many of them shed their skin at various times, revealing a

shiny new skin underneath. For this reason snakes have become symbols of

rebirth, transformation, immortality, and healing. The ancient Greeks

considered snakes sacred to Asclepius, the god of medicine. He carried a

caduceus, a staff with one or two serpents wrapped around it, which has become

the symbol of modern physicians.

For both the Greeks and the Egyptians, the snake represented eternity.

Ouroboros, the Greek symbol of eternity, consisted of a snake curled into a

circle or hoop, biting its own tail. The Ouroboros grew out of the belief that

serpents eat themselves and are reborn from themselves in an endless cycle of

destruction and creation.

Serpents figured prominently in archaic Greek myths. According to some

sources,

Ophion (“serpent”, a.k.a. Ophioneus), ruled the world with Eurynome

before the two of them were cast down by Cronus and Rhea. The oracles of the

Ancient Greeks were said to have been the continuation of the tradition begun

with the worship of the Egyptian cobra goddess,

Wadjet.

The

Minoan

Snake

Goddess brandished a serpent in either hand, perhaps evoking her role

as source of wisdom, rather than her role as Mistress of the Animals (Potnia

theron), with a leopard

under each arm. She is a Minoan version

of the Canaanite

fertility goddess

Asherah.

It is not by accident that later the infant

Heracles,

a liminal hero on the threshold between the old ways and the new Olympian world,

also brandished the two serpents that “threatened” him in his cradle. Classical

Greeks did not perceive that the threat was merely the threat of wisdom. But the

gesture is the same as that of the Cretan goddess.

Typhon

the enemy of the Olympian gods is described as a vast grisly monster with a

hundred heads and a hundred serpents issuing from his thighs, who was conquered

and cast into Tartarus

by

Zeus,

or confined beneath volcanic regions, where he is the cause of eruptions. Typhon

is thus the chthonic figuration of volcanic forces. Amongst his children by

Echidna are Cerberus

(a monstrous three-headed dog with a

snake for a tail and a serpentine mane), the serpent tailed

Chimaera

, the serpent-like chthonic water beast

Lernaean Hydra and the hundred-headed serpentine dragon

Ladon.

Both the Lernaean Hydra and Ladon were slain by

Heracles.

Python

was the earth-dragon of

Delphi,

she always was represented in the vase-paintings and by sculptors as a serpent.

Pytho was the chthonic enemy of Apollo

, who slew her and remade her former home

his own oracle, the most famous in Classical Greece.

Amphisbaena a Greek word, from amphis, meaning “both ways”, and

bainein, meaning “to go”, also called the “Mother of Ants”, is a mythological,

ant-eating serpent with a head at each end. According to Greek mythology, the

mythological amphisbaena was spawned from the blood that dripped from

Medusa

the Gorgon‘s

head as

Perseus flew over the Libyan Desert with her head in his hand.

Medusa and the other Gorgons were vicious female monsters with sharp fangs

and hair of living, venomous snakes whose origins predate the written myths of

Greece and who were the protectors of the most ancient ritual secrets. The

Gorgons wore a belt of two intertwined serpents in the same configuration of the

caduceus.

The Gorgon was placed at the highest point and central of the relief on the

Parthenon.

Asclepius, the son of Apollo and Koronis, learned the secrets of

keeping death at bay after observing one serpent bringing another (which

Asclepius himself had fatally wounded) healing herbs. To prevent the entire

human race from becoming immortal under Asclepius’s care, Zeus killed him with a

bolt of lightning. Asclepius’ death at the hands of Zeus illustrates man’s

inability to challenge the natural order that separates mortal men from the

gods. In honor of Asclepius, snakes were often used in healing rituals.

Non-poisonous snakes were left to crawl on the floor in dormitories where the

sick and injured slept. In

The Library

,

Apollodorus claimed that

Athena

gave Asclepius a vial of blood from the Gorgons. Gorgon blood had magical

properties: if taken from the left side of the Gorgon, it was a fatal poison;

from the right side, the blood was capable of bringing the dead back to life.

However

Euripides wrote in his tragedy

Ion

that the Athenian queen Creusa had

inherited this vial from her ancestor Erichthonios, who was a snake himself and

receiving the vial from Athena. In this version the blood of Medusa had the

healing power while the lethal poison originated from Medusa’s serpents.

Laocoön

was allegedly a priest of Poseidon

(or of Apollo, by some accounts) at

Troy;

he was famous for warning the Trojans in vain against accepting the Trojan Horse

from the Greeks, and for his subsequent divine execution. Poseidon (some say

Athena),

who was supporting the Greeks, subsequently sent sea-serpents to strangle

Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. Another tradition states

that Apollo sent the serpents for an unrelated offense, and only unlucky timing

caused the Trojans to misinterpret them as punishment for striking the Horse.

Olympias, the mother of

Alexander the Great

and a princess of the

primitive land of

Epirus

, had the reputation of a snake-handler,

and it was in serpent form that Zeus was said to have fathered Alexander upon

her; tame snakes were still to be found at Macedonian

Pella

in the 2nd century AD (Lucian,

Alexander the false prophet

) and at

Ostia

a bas-relief shows paired coiled serpents

flanking a dressed altar, symbols or embodiments of the

Lares

of the household, worthy of veneration (Veyne 1987 illus p 211).

Aeetes

, the king of

Colchis

and father of the sorceress Medea

, possessed the

Golden Fleece. He guarded it with a massive serpent that never slept.

Medea, who had fallen in love with Jason

of the

Argonauts,

enchanted it to sleep so Jason could seize the Fleece.

Amyntas III (died 370 BC), son of Arrhidaeus and father of

Philip II

, was king of

Macedon

in 393 BC, and again from 392 to 370

BC. He was also a paternal grandfather of

Alexander the Great

.

Reign

He came to the throne after the ten years of confusion which followed the

death of

Archelaus I

. But he had many enemies at home;

in 393 he was driven out by the

Illyrians

, but in the following year, with the

aid of the

Thessalians

, he recovered his kingdom. Medius,

head of the house of the

Aleuadae

of

Larissa

, is believed to have provided aid to

Amyntas in recovering his throne. The mutual relationship between the

Argeadae

and the Aleuadae dates to the time of

Archelaus.

To shore up his country against the threat of the Illyrians, Amyntas

established an alliance with the

Chalkidian League

led by

Olynthus

. In exchange for this support, Amyntas

granted them rights to Macedonian timber, which was sent back to Athens to help

fortify their fleet. With

money

flowing into Olynthus from these exports,

their power grew. In response, Amyntas sought additional allies. He established

connections with Kotys

, chief of the

Odrysians

. Kotys had already married his

daughter to the Athenian general

Iphicrates

. Prevented from marrying into Kotys’

family, Amyntas soon adopted Iphicrates as his son.

After the King’s Peace 387 BC,

Sparta

was anxious to re-establish its presence

in the north of Greece. In 385 BC,

Bardylis

and his

Illyrians

attacked

Epirus

instigated and aided by

Dionysius of Syracuse

,[1]

in an attempt to restore the

Molossian

king

Alcetas I of Epirus

to the throne. When Amyntas

sought Spartan aid against the growing threat of Olynthus, the Spartans eagerly

responded. That Olynthus was backed by Athens and Thebes, rivals to Sparta for

the control of Greece, provided them with an additional incentive to break up

this growing power in the north. Amyntas thus concluded a treaty with the

Spartans, who assisted him to reduce

Olynthus

(379). He also entered into a league

with

Jason of Pherae

, and assiduously cultivated the

friendship of Athens

. In 371 BC at a Panhellenic congress of

the

Lacedaemonian

allies, he voted in support of

the

Athenians

‘ claim and joined other Greeks in

voting to help Athens to recover possession of

Amphipolis

.[2][3]

With Olynthus defeated, Amyntas was now able to conclude a treaty with Athens

and keep the timber revenues for himself. Amyntas shipped the timber to the

house of the Athenian

Timotheus

, in the

Piraeus

.

Family

By his wife

Eurydice

, Amyntas had three sons,

Alexander II

,

Perdiccas III

and the youngest of whom was the

famous

Philip II of Macedon

. Amyntas died at an

advanced age, leaving his throne to his eldest son.

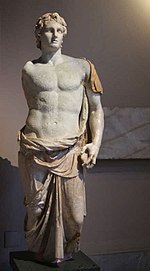

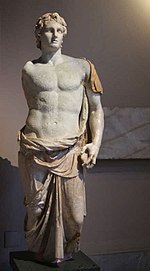

Alexander III of Macedon

, popularly known to history as Alexander

the Great,

(“Mégas Aléxandros“)

was an

Ancient Greek

king (basileus)

of

Macedon

. Born in 356 BC, Alexander succeeded his father

Philip II of Macedon

to the throne in 336 BC, and died in

Bablyon

in 323 BC at the age of 32.

Alexander was one of the most successful military commanders of all time and

it is presumed that he was undefeated in battle. By the time of his death, he

had conquered the

Achaemenid Persian Empire

, adding it to Macedon’s European territories;

according to some modern writers, this was much of the world then known to the

ancient Greeks (the ‘Ecumene‘).

His father, Philip, had unified most of the

city-states

of mainland Greece under Macedonian

hegemony

in

the

League of Corinth

. As well as inheriting hegemony over the Greeks, Alexander

also inherited the Greeks’ long-running feud with the

Achaemenid Empire

of

Persia

. After reconfirming Macedonian rule by quashing a rebellion of

southern Greek city-states, Alexander launched a short but successful campaign

against Macedon’s northern neighbours. He was then able to turn his attention

towards the east and the Persians. In a

series of campaigns

lasting 10 years, Alexander’s armies repeatedly defeated

the Persians in battle, in the process conquering the entirety of the Empire. He

then, following his desire to reach the ‘ends of the world and the Great Outer

Sea’, invaded India, but was eventually forced to turn back by the near-mutiny

of his troops.

Alexander died after twelve years of constant military campaigning, possibly

a result of malaria

, poisoning

,

typhoid fever

, viral

encephalitis

or the consequences of alcoholism. His legacy and conquests

lived on long after him and ushered in centuries of Greek settlement and

cultural influence over distant areas. This period is known as the

Hellenistic period

, which featured a combination of

Greek

,

Middle

Eastern

and

Indian culture

. Alexander himself featured prominently in the history and

myth of both Greek and non-Greek cultures. His exploits inspired a literary

tradition in which he appeared as a legendary

hero in the

tradition of Achilles

.

Alexander fighting Persian king Darius III. From Alexander

Mosaic, from Pompeii, Naples, Naples National

|