|

Greek city of Himera in Sicily

Bronze Hemilitron 14mm (2.76 grams) Struck 420-408 B.C.

Reference: Sear 1110; B.M.C. 2.54

Head of nymph Himera left, wearing sphendone; six pellets before.

Six pellets within laurel-wreath.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

A nymph in

Greek mythology

and in

Latin mythology

is a minor female nature deity typically associated with a

particular location or landform. There are 5 different types of nymphs,

Celestial Nymphs, Water Nymphs, Land Nymphs, Plant Nymphs and Underworld Nymphs.

Different from goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as divine spirits who

animate nature, and are usually depicted as beautiful, young

nubile

maidens

who love to dance and sing; their amorous freedom sets them apart from the

restricted and chaste wives and daughters of the Greek

polis

. They

are believed to dwell in mountains and

groves

, by springs and rivers, and also in trees and in valleys and cool

grottoes

.

Although they would never die of old age nor illness, and could give birth to

fully immortal children if mated to a god, they themselves were not necessarily

immortal, and could be beholden to death in various forms.

Charybdis

and Scylla

were

once nymphs.

Other nymphs, always in the shape of young maidens, were part of the

retinue

of a

god, such as Dionysus

, Hermes

, or

Pan

,

or a goddess, generally the huntress

Artemis

.[1]

Nymphs were the frequent target of

satyrs

. They are

frequently associated with the superior divinities: the huntress

Artemis

; the

prophetic Apollo

;

the reveller and god of wine

, Dionysus

; and rustic gods such as Pan and Hermes.

Etymology

Nymphs are personifications of the creative and fostering activities of

nature, most often identified with the life-giving outflow of springs: as

Walter Burkert

(Burkert 1985:III.3.3) remarks, “The idea that rivers are

gods and springs divine nymphs is deeply rooted not only in poetry but in belief

and ritual; the worship of these deities is limited only by the fact that they

are inseparably identified with a specific locality.”

The

Greek

word νύμφη has “bride” and

“veiled” among its meanings: hence a marriageable young woman. Other readers

refer the word (and also

Latin

nubere

and

German

Knospe) to a root expressing the idea of “swelling” (according

to

Hesychius

, one of the meanings of νύμφη

is “rose-bud”).

Greek deities

series |

|

Primordial deities

|

Titans

and

Olympians

|

|

Aquatic deities

|

|

Chthonic deities

|

Personified

concepts

|

|

Other deities |

-

Asclepius

, god of

medicine

- Leto

,

mother of

Apollo

and Artemis

-

Pan

,

shepherd

god

|

|

Nymphs |

- Alseid

-

Auloniad

- Aurai

-

Crinaeae

- Dryads

-

Eleionomae

-

Hamadryads

-

Hesperides

-

Limnades

- Meliae

|

- Naiads

- Napaeae

- Nereids

- Oceanids

- Oreads

- Pegaeae

-

Pegasides

-

Pleiades

-

Potamides

|

Adaptations

The Greek nymphs were spirits invariably bound to places, not unlike the

Latin genius loci

, and the difficulty of transferring their cult may be seen

in the complicated myth that brought

Arethusa

to Sicily. In the works of the Greek-educated

Latin poets

, the nymphs gradually absorbed into their ranks the indigenous

Italian divinities of springs and streams (Juturna,

Egeria

,

Carmentis

, Fontus

), while the

Lymphae

(originally Lumpae), Italian water-goddesses, owing to the accidental similarity

of their names, could be identified with the Greek Nymphae. The mythologies of

classicizing Roman poets were unlikely to have affected the rites and cult of

individual nymphs venerated by country people in the springs and clefts of

Latium

. Among

the Roman

literate class, their sphere of influence was restricted, and they

appear almost exclusively as divinities of the watery element.

In modern Greek

folklore

A Sleeping Nymph Watched by a Shepherd by

Angelica Kauffman

, about 1780, (V&A Museum no. 23-1886)

The ancient Greek belief in nymphs survived in many parts of the country into

the early years of the twentieth century, when they were usually known as “nereids“.

At that time, John Cuthbert Lawson wrote: “…there is probably no nook or

hamlet in all Greece where the womenfolk at least do not scrupulously take

precautions against the thefts and malice of the nereids, while many a man may

still be found to recount in all good faith stories of their beauty, passion and

caprice. Nor is it a matter of faith only; more than once I have been in

villages where certain Nereids were known by sight to several persons (so at

least they averred); and there was a wonderful agreement among the witnesses in

the description of their appearance and dress.”[2]

Nymphs tended to frequent areas distant from humans but could be encountered

by lone travelers outside the village, where their music might be heard, and the

traveler could spy on their dancing or bathing in a stream or pool, either

during the noon heat or in the middle of the night. They might appear in a

whirlwind. Such encounters could be dangerous, bringing dumbness, besotted

infatuation, madness or stroke to the unfortunate human. When parents believed

their child to be nereid-struck, they would pray to Saint Artemidos.[3][4]

Modern sexual

connotations

The Head of a Nymph by

Sophie Anderson

Due to the depiction of the mythological nymphs as females who mate with men

or women at their own volition, and are completely outside male control, the

term is often used for women who are perceived as behaving similarly. (For

example, the title of the

Perry

Mason

detective novel The Case of the Negligent Nymph (1956) by

Erle Stanley Gardner

is derived from this meaning of the word.)

The term

nymphomania

was created by modern

psychology

as referring to a “desire to engage in

human sexual behavior

at a level high enough to be considered clinically

significant”, nymphomaniac being the person suffering from such a

disorder. Due to widespread use of the term among lay persons (often shortened

to nympho) and stereotypes attached, professionals nowadays prefer the

term

hypersexuality

, which can refer to males and females alike.

The word

nymphet

is used to identify a sexually precocious girl. The term was

made famous in the novel

Lolita

by

Vladimir Nabokov

. The main character,

Humbert Humbert

, uses the term many times, usually in reference to the title

character.

Classification

As

H.J. Rose

states, all the names for various classes of nymphs are plural

feminine adjectives agreeing with the substantive nymphai, and there was

no single classification that could be seen as canonical and exhaustive. Thus

the classes of nymphs tend to overlap, which complicates the task of precise

classification. Rose mentions

dryads

and

hamadryads

as nymphs of trees generally,

meliai

as nymphs of

ash trees

, and naiads

as nymphs of water, but no others specifically.[5]

Classification by type of dwelling

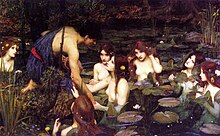

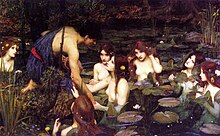

Hylas

and the Nymphs by

John William Waterhouse

, 1896

The following[6]

is not the authentic Greek classification, but is intended simply as a guide:

- Celestial nymphs

-

Aurae

(breezes), also called Aetae or Pnoae

- Asteriae (stars), mainly comprising the Atlantides (daughters of

Atlas

)

-

Hesperides

(nymphs of the West, daughters of Atlas; also had

attributes of the

Hamadryads

)

-

Aegle

(“dazzling light”)

-

Arethusa

-

Erytheia

(or Eratheis)

-

Hesperia

(or Hispereia)

-

Hyades

(star cluster; sent rain)

-

Pleiades

(daughters of

Atlas

and

Pleione

; constellation; also were classed as

Oreads

)

Himera (Greek:

Ἱμέρα), was an important

ancient Greek

city of

Sicily

,

situated on the north coast of the island, at the mouth of the river of the same

name (the modern

Grande

), between Panormus (modern

Palermo

) and

Cephaloedium (modern

Cefalù

). Its

remains lie within the borders of the modern

comune

of

Termini Imerese

.

Remains of the Temple of Victory.

Ideal reconstruction of the Temple of Victory.

//

History

Foundation

and earliest history

It was the first Greek settlement on this part of the island and was a

strategic outpost just outside the eastern boundary of the

Carthaginian

-controlled west.

Thucydides

says it was the only Greek city on this coast of Sicily,[1]

which must however be understood with reference only to independent cities;

Mylae

, which was also on the north coast, and certainly of Greek origin,

being a dependency of

Zancle

(modern

Messina

). All

authorities agree that Himera was a colony of Zancle, but Thucydides tells us

that, with the emigrants from Zancle, who were of Chalcidic origin, were mingled

a number of

Syracusan

exiles, the consequence of which was, that, though the

institutions (νόμιμα) of the new city

were Chalcidic, its dialect had a mixture of

Doric

.

The foundation of Himera is placed subsequent to that of Mylae (as, from

their relative positions, might naturally have been expected) both by

Strabo

and

Scymnus Chius

:

its date is not mentioned by Thucydides, but

Diodorus

tells us that it had existed 240 years at the time of its

destruction by the Carthaginians, which would fix its first settlement in

648 BCE

.[2]

We have very little information as to its early history: an obscure notice in

Aristotle

,[3]

from which it appears to have at one time fallen under the dominion of the

tyrant Phalaris

,

being the only mention we find of it, until about

490 BCE

,

when it afforded a temporary refuge to

Scythes

,

tyrant of Zancle, after his expulsion from the latter city.[4]

Not long after this event, Himera fell itself under the yoke of a despot named

Terillus

,

who sought to fortify his power by contracting a close alliance with

Anaxilas

,

at that time ruler both of Rhegium (modern

Reggio di Calabria

) and Zancle. But Terillus was unable to resist the power

of

Theron

,

despot of Agrigentum (modern

Agrigento

),

and, being expelled by him from Himera, had recourse to the assistance of the

Carthaginians, a circumstance which became the immediate occasion of the first

great expedition of that people to Sicily,

480 BCE

.[5]

First

interaction with Carthage

The magnitude of the armament sent under

Hamilcar

,

who is said to have landed in Sicily with an army of 300,000 men, in itself

sufficiently proves that the conquest of Himera was rather the pretext, than the

object, of the war: but it is likely that the growing power of that city, in the

immediate neighborhood of the Carthaginian settlements of Panormus and

Solus

, had already given umbrage to the latter people. Hence it was against

Himera that the first efforts of Hamilcar were directed: but Theron, who had

thrown himself into the city with all the forces at his command, was able to

maintain its defence till the arrival of

Gelon of Syracuse

, who, notwithstanding the numerical inferiority of his

forces, defeated the vast army of the Carthaginians with such slaughter that the

Battle of Himera

was regarded by the Greeks of Sicily as worthy of

comparison with the contemporary victory of

Salamis

.[6]

The same feeling probably gave rise to the tradition or belief, that both

triumphs were achieved on the very same day.[7]

After

the Battle of Himera

This great victory left Theron in the undisputed possession of the

sovereignty of Himera, as well as of that of Agrigentum; but he appears to have

bestowed his principal attention upon the latter city, and consigned the

government of Himera to his son

Thrasydaeus

. But the young man, by his violent and oppressive rule, soon

alienated the minds of the citizens, who in consequence applied for relief to

Hieron of Syracuse

, at that time on terms of hostility with Theron. The

Syracusan despot, however, instead of lending assistance to the discontented

party at Himera, betrayed their overtures to Theron, who took signal vengeance

on the unfortunate Himeraeans, putting to death a large number of the

disaffected citizens, and driving others into exile.[8]

Shortly after, seeing that the city had suffered greatly from these severities,

and that its population was much diminished, he sought to restore its prosperity

by establishing there a new body of citizens, whom he collected from various

quarters. The greater part of these new colonists were of

Dorian

extraction; and though the two bodies of citizens were blended into one, and

continued to live harmoniously together, we find that from this period Himera

became a Doric city, and both adopted the institutions, and followed the policy,

of the other Doric states of Sicily.[9]

This settlement seems to have taken place in

476 BCE

,[10]

and Himera continued subject to Theron till his death, in

472 BCE

: but Thrasydaeus retained possession of the sovereignty for a very

short time after the death of his father, and his defeat by Hieron of Syracuse

was speedily followed by his expulsion both from Agrigentum and Himera.[11]

In

466 BCE

we find the Himeraeans, in their turn, sending a force to assist the

Syracusans in throwing off the yoke of

Thrasybulus

; and, in the general settlement of affairs which followed soon

after, the exiles were allowed to return to Himera, where they appear to have

settled quietly together with the new citizens.

[12]

From

this period Diodorus expressly tells us that Himera was fortunate enough to

escape from civil dissensions,[13]

and this good government must have secured to it no small share of the

prosperity which was enjoyed by the Sicilian cities in general during the

succeeding half-century.

But though we are told in general terms that the period which elapsed from

this re-settlement of Himera till its destruction by the Carthaginians (461–408

BCE), was one of peace and prosperity, the only notices we find of the city

during this interval refer to the part it took at the time of the

Athenian

expedition to Sicily,

415 BCE

. On that occasion, the Himeraeans were among the first to promise

their support to Syracuse: hence, when

Nicias

presented himself before their port with the Athenian fleet, they altogether

refused to receive him; and, shortly after, it was at Himera that

Gylippus

landed, and from whence he marched across the island to Syracuse, at the head of

a force composed in great part of Himeraean citizens.[14]

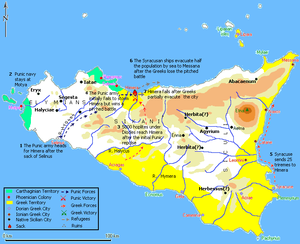

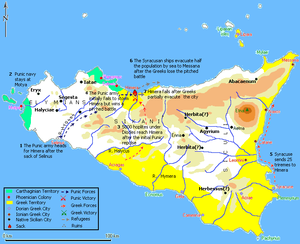

Destruction

by Carthage

A few years after this the prosperity of the city was brought to a sudden and

abrupt termination by the great Carthaginian expedition to Sicily,

408 BCE

. Though the ostensible object of that armament, as it had been of

the Athenian, was the support of the

Segestans

against their neighbors, the

Selinuntines

,

yet there can be no doubt that the Carthaginians, from the first, entertained

more extensive designs; and, immediately after the destruction of Selinus,

Hannibal Mago

, who commanded the expedition, hastened to turn his arms

against Himera. That city was ill-prepared for defence; its fortifications were

of little strength, but the citizens made a desperate resistance, and by a

vigorous sally inflicted severe loss on the Carthaginians. They were at first

supported by a force of about 4000 auxiliaries from Syracuse, under the command

of

Diocles

; but that general became seized with a panic fear for the safety of

Syracuse itself, and precipitately abandoned Himera, leaving the unfortunate

citizens to contend singlehanded against the Carthaginian power. The result

could not be doubtful, and the city was soon taken by storm: a large part of the

citizens were put to the sword, and not less than 3000 of them, who had been

taken prisoners, were put to death in cold blood by Hannibal, as a sacrifice to

the memory of his grandfather Hamilcar.[15]

The city itself was utterly destroyed, its buildings razed to the ground, and

even the temples themselves were not spared; the Carthaginian general being

evidently desirous to obliterate all trace of a city whose name was associated

with the great defeat of his countrymen.

Diodorus, who relates the total destruction of Himera, tells us expressly

that it was never rebuilt, and that the site remained uninhabited down to his

own times.[16]

It seems at first in contradiction with this statement, that he elsewhere

includes the Himeraeans, as well as the Selinuntines and Agrigentines, among the

exiled citizens that were allowed by the treaty, concluded with Carthage, in

405 BCE

, to return to their homes, and inhabit their own cities, on

condition of paying tribute to Carthage and not restoring their fortifications.

[17]

And it

seems clear that many of them at least availed themselves of this permission, as

we find the Himeraeans subsequently mentioned among the states that declared in

favour of

Dionysius I of Syracuse

, at the commencement of his great war with Carthage

in

397 BCE

; though they quickly returned to the Carthaginian alliance in the

following year.[18]

The explanation of this difficulty is furnished by

Cicero

, who

tells us that, after the destruction of Himera, those citizens who had survived

the calamity of the war established themselves at

Thermae

, within

the confines of the same territory, and not far from their old town.[19]

Diodorus gives a somewhat different account of the foundation of Thermae, which

he represents as established by the Carthaginians themselves before the close of

the war, in

407 BCE

.[20]

But it is probable that both statements are substantially correct, and that the

Carthaginians founded the new town in the immediate neighbourhood of Himera, in

order to prevent the old site being again occupied; while the Himeraean exiles,

when they returned thither, though they settled in the new town, naturally

regarded themselves as still the same people, and would continue to bear the

name of Himeraeans. How completely, even at a much later period, the one city

was regarded as the representative of the other, appears from the statement of

Cicero, that when

Scipio Africanus

, after the capture of Carthage, restored to the

Agrigentines and Gelenses the statues that had been carried off from their

respective cities, he at the same time restored to the citizens of Thermae those

that had been taken from Himera.[21]

Hence we cannot be surprised to find that, not only are the Himeraeans still

spoken of as an existing people, but even that the name of Himera itself is

sometimes inadvertently used as that of their city. Thus, in

314 BCE

, Diodorus tells us that, by the treaty between

Agathocles

and the Carthaginians, it was stipulated that

Heracleia

, Selinus, and Himera should continue subject to Carthage as they

had been before.

[22]

It is

much more strange that we find the name of Himera reappear both in

Mela and

Pliny

, though we

know from the distinct statements of Cicero and Strabo, as well as Diodorus,

that it had ceased to exist centuries before.[23]

Foundation

of Thermae

Main article:

Termini Imerese

The new town of Thermae or Therma called for the sake of distinction Thermae

Himerenses,[24]

which thus took the place of Himera, obviously derived its name from the hot

springs for which it was celebrated, and the first discovery of which was

connected by legends with the wanderings of

Hercules

.[25]

It appears to have early become a considerable town, though it continued, with

few and brief exceptions, to be subject to the Carthaginian rule. In the

First Punic War its

name is repeatedly mentioned. Thus, in

260 BCE

, a body of

Roman

troops were encamped in the neighborhood, when they were attacked by

Hamilcar

,

and defeated with heavy loss.[26]

Before the close of the war, Thermae itself was besieged and taken by the

Romans.[27]

Cicero relates that the Roman government restored to the Thermitani their city

and territory, with the free use of their own laws, as a reward for their steady

fidelity.

[28]

They

were on hostile terms with Rome during the First Punic War, so it can only be to

the subsequent period that these expressions apply; but the occasion to which

they refer is unknown. In the time of Cicero, Thermae appears to have been a

flourishing place, carrying on a considerable amount of trade, though the orator

speaks, of it as oppidum non maximum.[29]

It seems to have received a

colony

in

the time of Augustus

, whence we find mention in inscriptions of the Ordo et Populus

splendidissimae Coloniae Augustae Himeraeorum Thermitanorum:

[30]

and

there can be little doubt that the Thermae colonia of

Pliny

in reality

refers to this town, though he evidently understood it to be Thermae Selinuntiae

(modern Sciacca

),

as he places it on the south coast between Agrigentum and Selinus.

[31]

There

is little subsequent account of Thermae; but, as its name is found in

Ptolemy

and

the Itineraries, it appears to have continued in existence throughout the period

of the Roman Empire

, and probably never ceased to be inhabited, as the modern town

of

Termini Imerese

retains the ancient site as well as name.[32]

The magnificence of the ancient city, and the taste of its citizens for the

encouragement of art, are attested by Cicero, who calls it in primis Siciliae

clarum et ornatum; and some evidence of it remained, even in the days of

that orator, in the statues preserved by the Thermitani, to whom they had been

restored by Scipio, after the conquest of Carthage; and which were valuable, not

only as relics of the past, but from their high merit as works of art.[33]

The numerous examples of coins from Himera testify to the city’s wealth in

antiquity.

Current

situation

Because of extensive remains, no doubt can therefore exist with regard to the

site of Thermae, which would be, indeed, sufficiently marked by the hot springs

themselves; but the exact position of the more ancient city of Himera was a

subject of controversy until recent times. The opinion of

Cluverius

, which has been followed by almost all subsequent writers into the

19th century, would place it on the left bank of the river which flows by

Termini on the west, and is thence commonly known as the Fiume di Termini,

though called in the upper part of its course Fiume San Leonardo. On this

supposition the inhabitants merely removed from one bank of the river to the

other; and this would readily explain the passages in which Himera and Thermae

appear to be regarded as identical, and where the river Himera (which

unquestionably gave name to the older city) is represented at the same time as

flowing by Thermae.[34]

On the other hand, there is great difficulty in supposing that the Fiume San

Leonardo can be the river Himera; and all our data with regard to the latter

would seem to support which the view of

Fazello

, who identifies it with the

Fiume Grande

, the mouth of which is distant just 8 miles from Termini. This

is the view adopted by most modern scholarship.[35]

This distance can hardly be said to be too great to be reconciled with Cicero’s

expression, that the new settlement was established non longe ab oppido

antique;[36]

while the addition that it was in the same territory

[37]

would

seem to imply that it was not very near the old site. It may be added, that, in

this case, the new site would have had the recommendation in the eyes of the

Carthaginians of being nearer to their own settlements of Solus and Panormus,

and, consequently, more within their command. But Fazello’s view derives a

strong confirmation from the circumstance, stated by him, that the site which he

indicates, marked by the Torre di Bonfornello on the seacoast (on the left bank

of the Fiume Grande, close to its mouth), though presenting no ruins, abounded

in ancient relics, such as vases and bronzes; and numerous sepulchres had also

been brought to light.[38]

On the other hand, neither Cluverius nor any other writer has noticed the

existence of any ancient remains on the west bank of the Himera; nor does it

appear that the site so fixed is one adapted for a city of importance.

Archaeology

The only recognizable ruin in this city is the Tempio della Vittoria (Temple

of Victory), a

Doric

structure supposedly built to commemorate the defeat of the Carthaginians

(although recently some scholars have come to doubt this hypothesis). To the

south of the temple was the town’s

necropolis

. Some artifacts recovered from this site are kept in a small

antiquarium

. However, the more impressive displays are in

Palermo

‘s

Museo Archeologico Regionale.

Famous

people

Himera was celebrated in antiquity as the birth place of the poet

Stesichorus

, who appears, from an anecdote preserved by

Aristotle

,

to have taken considerable part in the political affairs of his native city. His

statue was still preserved at Thermae in the days of Cicero, and regarded with

the utmost veneration.

Ergoteles

, whose victory at the

Olympic games

is celebrated by

Pindar

, was a

citizen, but not a native, of Himera.

On the other hand, Thermae had the honour of being the birthplace of the tyrant

Agathocles

.

|