Modern-era

|

|

Licinius I (Latin:

Gaius Valerius Licinianus Licinius Augustus[note

1 c. 263 – 325), was

Roman Emperor

from 308 to 324. For the majority

of his reign he was the colleague and rival of

Constantine I

, with whom he co-authored the

Edict of Milan

that granted official toleration

to Christians in the Roman Empire. He was finally defeated at the

Battle of Chrysopolis

, before being executed on

the orders of Constantine I.

Constantine I

(right).

Early reign

Born to a Dacian

[5][6]

peasant family in Moesia

Superior, Licinius accompanied his close

childhood friend, the future emperor

Galerius

, on the Persian expedition in 298.[5]

He was trusted enough by Galerius that in 307 he was sent as an envoy to

Maxentius

in

Italy

to attempt to reach some agreement about

his illegitimate status.[5]

Galerius then trusted the eastern provinces to Licinius when he went to deal

with Maxentius personally after the death of

Flavius Valerius Severus

.[7]

Upon his return to the east Galerius elevated Licinius to the rank of

Augustus in the West

on November 11, 308. He

received as his immediate command the provinces of

Illyricum

,

Thrace

and

Pannonia

.[6]

In 310 he took command of the war against the

Sarmatians

, inflicting a severe defeat on them

and emerging victorious.[3]

On the death of Galerius in May 311, Licinius entered into an agreement with

Maximinus II

(Daia) to share the eastern

provinces between them. By this point, not only was Licinius the official

Augustus of the west, but he also possessed part of the eastern provinces as

well, as the

Hellespont

and the

Bosporus

became the dividing line, with

Licinius taking the European provinces and Maximinus taking the Asian.[6]

An alliance between Maximinus and Maxentius forced the two remaining emperors

to enter into a formal agreement with each other.[7]

So in March 313 Licinius married

Flavia Julia Constantia

, half-sister of

Constantine I

,[4]

at Mediolanum (now Milan

); they had a son,

Licinius the Younger

, in 315. Their marriage

was the occasion for the jointly-issued “Edict

of Milan” that reissued Galerius’ previous edict allowing

Christianity

to be professed in the Empire,[6]

with additional dispositions that restored confiscated properties to Christian

congregations and exempted Christian clergy from municipal civic duties.[8]

The redaction of the edict as reproduced by

Lactantius

– who follows the text affixed by

Licinius in Nicomedia

on June 14 313, after Maximinus’

defeat – uses a neutral language, expressing a will to propitiate “any Divinity

whatsoever in the seat of the heavens”.

Coin of Licinius

Daia in the meantime decided to attack Licinius. Leaving Syria with 70,000

men, he reached Bithynia

, although harsh weather he encountered

along the way had gravely weakened his army. In April 313, he crossed the

Bosporus

and went to

Byzantium

, which was held by Licinius’ troops.

Undeterred, he took the town after an eleven-day siege. He moved to Heraclea,

which he captured after a short siege, before moving his forces to the first

posting station. With a much smaller body of men, possibly around 30,000,[10]

Licinius arrived at

Adrianople

while Daia was still besieging

Heraclea

. Before the decisive engagement,

Licinius allegedly had a vision in which an angel recited him a generic prayer

that could be adopted by all cults and which Licinius then repeated to his

soldiers.[11]

On 30 April 313, the two armies clashed at the

Battle of Tzirallum

, and in the ensuing battle

Daia’s forces were crushed. Ridding himself of the imperial purple and dressing

like a slave, Daia fled to

Nicomedia

.[7]

Believing he still had a chance to come out victorious, Daia attempted to stop

the advance of Licinius at the

Cilician Gates

by establishing fortifications

there. Unfortunately for Daia, Licinius’ army succeeded in breaking through,

forcing Daia to retreat to

Tarsus

where Licinius continued to press him on

land and sea. The war between them only ended with Daia’s death in August 313.[6]

Given that Constantine had already crushed his rival Maxentius in 312, the

two men decided to divide the Roman world between them. As a result of this

settlement, Licinius became sole Augustus in the East, while his brother-in-law,

Constantine, was supreme in the West. Licinius immediately rushed to the east to

deal with another threat, this time from the Persian

Sassanids

.[7]

Conflict with

Constantine I

In 314, a civil war erupted between Licinius and Constantine, in which

Constantine used the pretext that Licinius was harbouring Senecio, whom

Constantine accused of plotting to overthrow him.[7]

Constantine prevailed at the

Battle of Cibalae

in

Pannonia

(October 8, 314).[6]

Although the situation was temporarily settled, with both men sharing the

consulship

in 315, it was but a lull in the

storm. The next year a new war erupted, when Licinius named

Valerius Valens

co-emperor,[4]

only for Licinius to suffer a humiliating defeat on the plain of

Mardia

(also known as

Campus Ardiensis

) in

Thrace

. The emperors were reconciled after

these two battles and Licinius had his co-emperor Valens killed.[6]

Over the next ten years, the two imperial colleagues maintained an uneasy

truce.[7]

Licinius kept himself busy with a campaign against the Sarmatians in 318,[6]

but temperatures rose again in 321 when Constantine pursued some Sarmatians, who

had been ravaging some territory in his realm, across the Danube into what was

technically Licinius’s territory.[6]

When he repeated this with another invasion, this time by the

Goths

who were pillaging

Thrace

, Licinius complained that Constantine

had broken the treaty between them.

Constantine wasted no time going on the offensive. Licinius’s fleet of 350

ships was defeated by Constantine I’s fleet in 323. Then in 324, Constantine,

tempted by the “advanced age and unpopular vices”[7]

of his colleague, again declared war against him, and, having defeated his army

of 170,000 men[dubious

] at the

Battle of Adrianople

(July 3, 324), succeeded

in shutting him up within the walls of

Byzantium

.[6]

The defeat of the superior fleet of Licinius in the

Battle of the Hellespont

by

Crispus

, Constantine’s eldest son and

Caesar

, compelled his withdrawal to

Bithynia

, where a last stand was made; the

Battle of Chrysopolis

, near

Chalcedon

(September 18), resulted in Licinius’

final submission.[7]

While Licinius’ co-emperor

Sextus Martinianus

was killed, Licinius himself

was spared due to the pleas of his wife, Constantine’s sister, and interned at

Thessalonica

.[4]

The next year, Constantine had him hanged, accusing him of conspiring to raise

troops among the barbarians.[7]

Character and legacy

Constantine made every effort to blacken the reputation of his imperial

colleague. To this end, stories began circulating about Licinius’s cruelty. It

was said that he had put to death Severianus, the son of the emperor Severus, as

well as Candidianus, the son of Galerius.[7]

To this was added the execution of the wife and daughter of the Emperor

Diocletian

, who had fled from the court of

Licinius before being discovered at

Thessalonica

.[7]

Much of this can be considered imperial propaganda on the part of Constantine.

In addition, as part of Constantine’s attempts to decrease Licinius’s

popularity, he actively portrayed his brother-in-law as a pagan supporter. This

was not the case; contemporary evidence tends to suggest that he was at least a

committed supporter of Christians.[4]

He co-authored the Edict of Milan which ended the

Great Persecution

, and re-affirmed the rights

of Christians in his half of the empire. He also added the Christian symbol to

his armies, and attempted to regulate the affairs of the Church hierarchy just

as Constantine and his successors were to do. His wife was a devout Christian.[12]

It is even a possibility that he converted.[4]

However,

Eusebius of Caesarea

, writing under the rule of

Constantine, charges him with expelling Christians from the Palace and ordering

military sacrifice, as well as interfering with the Church’s internal procedures

and organization.[13]

According to Eusebius, this turned what appeared to be a committed Christian

into a man who feigned sympathy for the sect but who eventually exposed his true

bloodthirsty pagan nature, only to be stopped by the virtuous Constantine.[4]

repoussé

silver

disc of Sol Invictus (3rd

century), found at

Pessinus

(British

Museum)

Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) was the official

sun god

of the later

Roman Empire

and a patron of soldiers. In 274

the Roman emperor

Aurelian

made it an official

cult alongside the traditional Roman cults. Scholars disagree whether

the new deity was a refoundation of the ancient

Latin

cult of

Sol

,

a revival of the cult of

Elagabalus

or completely new.The god was

favored by emperors after Aurelian and appeared on their coins until

Constantine

.The last inscription referring to

Sol Invictus dates to 387 AD and there were enough devotees in the 5th century

that

Augustine

found it necessary to preach against

them.

It is commonly claimed that the date of 25 December for

Christmas

was selected in order to correspond

with the Roman festival of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or “Birthday of

the Unconquered Sun”, but this view is challenged

Invictus as

epithet

Invictus

(“Unconquered, Invincible”) was an

epithet

for

several deities

of

classical Roman religion

, including the supreme

deity

Jupiter

, the war god

Mars

,

Hercules

,

Apollo

and

Silvanus

.[8]

Invictus was in use from the 3rd century BC, and was well-established as

a

cult

title when applied to

Mithras

from the 2nd century onwards. It has a

clear association[vague]

with solar deities and solar monism; as such, it became the preferred epithet of

Rome’s traditional

Sol

and the novel, short-lived Roman state cult

to

Elagabalus

, an

Emesan

solar deity who headed Rome’s official

pantheon under his

namesake emperor

.

The earliest dated use of Sol invictus is in a dedication from Rome,

AD 158. Another, stylistically dated to the 2nd century AD, is inscribed on a

Roman

phalera

: “inventori lucis soli invicto

augusto” (to the contriver of light, sol invictus augustus ). Here

“augustus” is most likely a further epithet of Sol as “august” (an elevated

being, divine or close to divinity), though the association of Sol with the

Imperial house would have been unmistakable and was already established in

iconography and stoic monism. These are the earliest attested examples of Sol as

invictus, but in AD 102 a certain

Anicetus

restored a shrine of Sol; Hijmans

(2009, 486, n. 22) is tempted “to link Anicetus’ predilection for Sol with his

name, the

Latinized

form of the Greek word ἀνίκητος,

which means invictus“.

Elagabalus

The first sun god consistently termed invictus was the

provincial Syrian

god

Elagabalus

. According to the

Historia Augusta

, the

teenaged Severan heir

adopted the name of his

deity and brought his cult image from Emesa to Rome. Once installed as emperor,

he neglected Rome’s traditional State deities and promoted his own as Rome’s

most powerful deity. This ended with his murder in 222.

The Historia Augusta refers to the deity Elagabalus as “also called

Jupiter and Sol” (fuit autem Heliogabali vel Iovis vel Solis).This has

been seen as an abortive attempt to impose the Syrian sun god on Rome;

but because it is now clear that the Roman cult of Sol remained

firmly established in Rome throughout the Roman period,this Syrian

Sol Elagabalus

has become no more relevant to

our understanding of the Roman

Sol

than, for example, the Syrian

Jupiter Dolichenus

is for our understanding of

the Roman Jupiter.

Sol Invictus

Aurelian

The Roman gens

Aurelian was associated with the cult

of Sol. After his victories in the East, the Emperor

Aurelian

thoroughly reformed the Roman cult of

Sol, elevating the sun-god to one of the premier divinities of the Empire. Where

previously priests of Sol had been simply

sacerdotes

and tended to belong to lower

ranks of Roman society, they were now pontifices and members of the new

college of pontifices

instituted by Aurelian.

Every pontifex of Sol was a member of the senatorial elite, indicating that the

priesthood of Sol was now highly prestigious. Almost all these senators held

other priesthoods as well, however, and some of these other priesthoods take

precedence in the inscriptions in which they are listed, suggesting that they

were considered more prestigious than the priesthood of Sol.Aurelian also built

a new temple for Sol, bringing the total number of temples for the god in Rome

to (at least) four[21]

He also instituted games in honor of the sun god, held every four years from AD

274 onwards.

The identity of Aurelian’s Sol Invictus has long been a subject of scholarly

debate. Based on the

Historia Augusta

, some scholars have argued

that it was based on

Sol Elagablus

(or Elagabla) of

Emesa

. Others, basing their argument on

Zosimus

, suggest that it was based on the

Helios

, the solar god of

Palmyra

on the grounds that Aurelian placed and

consecrated a cult statue of Helios looted from Palmyra in the temple of Sol

Invictus. Professor Gary Forsythe discusses these arguments and add a third more

recent one based on the work of Steven Hijmans. Hijmans argues that Aurelian’s

solar deity was simply the traditional Greco-Roman Sol Invictus.

Constantine

Emperors portrayed Sol Invictus on their official coinage, with a wide range

of legends, only a few of which incorporated the epithet invictus, such

as the legend SOLI INVICTO COMITI, claiming the Unconquered Sun

as a companion to the Emperor, used with particular frequency by Constantine.

Statuettes of Sol Invictus, carried by the standard-bearers,

appear in three places in reliefs on the

Arch of Constantine

. Constantine’s official

coinage continues to bear images of Sol until 325/6. A

solidus

of Constantine as well as a gold

medallion from his reign depict the Emperor’s bust in profile twinned (“jugate”)

with Sol Invictus, with the legend INVICTUS CONSTANTINUS

Constantine decreed (March 7, 321) dies Solis—day of the sun, “Sunday“—as

the Roman day of rest [CJ3.12.2]:

- On the venerable day of the Sun let the magistrates and people residing

in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed. In the country however

persons engaged in agriculture may freely and lawfully continue their

pursuits because it often happens that another day is not suitable for

grain-sowing or vine planting; lest by neglecting the proper moment for such

operations the bounty of heaven should be lost.

Constantine’s triumphal arch was carefully positioned to align with the

colossal statue of Sol

by the

Colosseum

, so that Sol formed the dominant

backdrop when seen from the direction of the main approach towards the arch.[26]

Sol and the

other Roman Emperors

Berrens

deals with coin-evidence of Imperial connection to the Solar

cult. Sol is depicted sporadically on imperial coins in the 1st and 2nd

centuries AD, then more frequently from

Septimius Severus

onwards until AD 325/6.

Sol invictus appears on coin legends from AD 261, well before the reign of

Aurelian.

Connections between the imperial radiate crown and the cult of

Sol are postulated.

Augustus

was posthumously depicted with radiate

crown, as were living emperors from

Nero (after AD 65) to

Constantine

. Some modern scholarship interprets

the imperial radiate crown as a divine, solar association rather than an overt

symbol of Sol; Bergmann calls it a pseudo-object designed to disguise the divine

and solar connotations that would otherwise be politically controversial

but there is broad agreement that coin-images showing the

imperial radiate crown are stylistically distinct from those of the solar crown

of rays; the imperial radiate crown is depicted as a real object rather than as

symbolic light. Hijmans argues that the Imperial radiate crown represents the

honorary wreath awarded to

Augustus

, perhaps posthumously, to commemorate

his victory at the

battle of Actium

; he points out that

henceforth, living emperors were depicted with radiate crowns, but state divi

were not. To Hijmans this implies the radiate crown of living emperors as a link

to Augustus. His successors automatically inherited (or sometimes acquired) the

same offices and honours due to Octavian as “saviour of the Republic” through

his victory at Actium, piously attributed to Apollo-Helios. Wreaths awarded to

victors at the Actian Games were radiate.

Sol

Invictus and Christianity and Judaism

Sol

or

Apollo-Helios

in Mausoleum M in the

pre-4th-century necropolis beneath[33]

St. Peter’s in the Vatican

, which

many interpret as representing Christ

The

Philocalian calendar

of AD 354 gives a festival

of “Natalis Invicti” on 25 December. There is limited evidence that this

festival was celebrated before the mid-4th century.

The idea that Christians chose to celebrate the birth of Jesus on 25 December

because this was the date of an already existing festival of the Sol Invictus

was expressed in an annotation to a manuscript of a work by 12th-century Syrian

bishop

Jacob Bar-Salibi

. The scribe who added it

wrote: “It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the

birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In

these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when

the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this

festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be

solemnised on that day.”

This idea became popular especially in the 18th and 19th centuries

and is still widely accepted.

In the judgement of the Church of England Liturgical Commission, this view

has been seriously challenged

by a view based on an old tradition, according to which the

date of Christmas was fixed at nine months after 25 March, the date of the

vernal equinox, on which the

Annunciation

was celebrated.

The Jewish calendar date of 14 Nisan was believed to be that

of the beginning of creation, as well as of the Exodus and so of Passover, and

Christians held that the new creation, both the death of Jesus and the beginning

of his human life, occurred on the same date, which some put at 25 March in the

Julian calendar.[40][42][43]

It was a traditional Jewish belief that great men lived a whole number of years,

without fractions, so that Jesus was considered to have been conceived on 25

March, as he died on 25 March, which was calculated to have coincided with 14

Nisan.[44]

Sextus Julius Africanus

(c.160 – c.240) gave 25

March as the day of creation and of the conception of Jesus.

The tractate De solstitia et aequinoctia conceptionis et

nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae falsely

attributed to

John Chrysostom

also argued that Jesus was

conceived and crucified on the same day of the year and calculated this as 25

March.

A passage of the Commentary on the prophet Daniel by

Hippolytus of Rome

, written in about 204, has

also been appealed to.

Among those who have put forward this view are Louis Duchesne,Thomas J.

Talley, David J. Rothenberg, J. Neil Alexander, and Hugh Wybrew.

Not all scholars who view the celebration of the birth of Jesus on 25

December as motivated by the choice of the winter solstice rather than

calculated on the basis of the belief that he was conceived and died on 25 March

agree that it constituted a deliberate Christianization of a festival of the

Birthday of the Unconquered Sun. Michael Alan Anderson writes:

Both the sun and Christ were said to be born anew on December 25. But

while the solar associations with the birth of Christ created powerful

metaphors, the surviving evidence does not support such a direct association

with the Roman solar festivals. The earliest documentary evidence for the

feast of Christmas makes no mention of the coincidence with the winter

solstice. Thomas Talley has shown that, although the Emperor Aurelian’s

dedication of a temple to the sun god in the Campus Martius (C.E. 274)

probably took place on the ‘Birthday of the Invincible Sun’ on December 25,

the cult of the sun in pagan Rome ironically did not celebrate the winter

solstice nor any of the other quarter-tense days, as one might expect. The

origins of Christmas, then, may not be expressly rooted in the Roman

festival.

The same point is made by Hijmans: “It is cosmic symbolism…which inspired

the Church leadership in Rome to elect the southern solstice, December 25, as

the birthday of Christ … While they were aware that pagans called this day the

‘birthday’ of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any

role in their choice of date for Christmas.” He also states that, “while the

winter solstice on or around December 25 was well established in the Roman

imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on

that day antedated the celebration of Christmas”.

The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought also remarks on the

uncertainty about the order of precedence between the celebrations of the

Birthday of the Unconquered Sun and the birthday of Jesus: “This ‘calculations’

hypothesis potentially establishes 25 December as a Christian festival before

Aurelian’s decree, which, when promulgated, might have provided for the

Christian feast both opportunity and challenge.”

Susan K. Roll also calls “most extreme” the unproven hypothesis that “would

call Christmas point-blank a ‘christianization’ of Natalis Solis Invicti, a

direct conscious appropriation of the pre-Christian feast, arbitrarily placed on

the same calendar date, assimilating and adapting some of its cosmic symbolism

and abruptly usurping any lingering habitual loyalty that newly-converted

Christians might feel to the feasts of the state gods”.

The comparison of Christ with the astronomical

Sun

is common in ancient Christian writings.

In the 5th century,

Pope Leo I

(the Great) spoke in several sermons

on the Feast of the Nativity of how the celebration of Christ’s birth coincided

with increase of the sun’s position in the sky. An example is: “But this

Nativity which is to be adored in heaven and on earth is suggested to us by no

day more than this when, with the early light still shedding its rays on nature,

there is borne in upon our senses the brightness of this wondrous mystery.

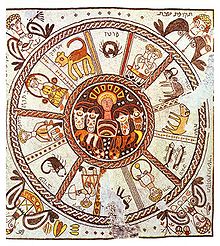

Beth Alpha

synagogue, with the sun

in the centre, surrounded by the twelve zodiac constellations and

with the four seasons associated inaccurately with the

constellations

A study of

Augustine of Hippo

remarks that his exhortation

in a Christmas sermon, “Let us celebrate this day as a feast not for the sake of

this sun, which is beheld by believers as much as by ourselves, but for the sake

of him who created the sun”, shows that he was aware of the coincidence of the

celebration of Christmas and the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun, although this

pagan festival was celebrated at only a few places and was originally a

peculiarity of the Roman city calendar. It adds: “He also believes, however,

that there is a reliable tradition which gives 25 December as the actual date of

the birth of our Lord.”

By “the sun of righteousness” in

Malachi 4:2

“the

fathers

, from

Justin

downward, and nearly all the earlier

commentators understand Christ, who is supposed to be described as the

rising sun”.

The

New Testament

itself contains a hymn fragment:

“Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you.”

Clement of Alexandria

wrote of “the Sun of the

Resurrection, he who was born before the dawn, whose beams give light”.

Christians adopted the image of the Sun (Helios

or Sol Invictus) to represent Christ. In this portrayal he is a beardless figure

with a flowing cloak in a chariot drawn by four white horses, as in the mosaic

in Mausoleum M discovered under

Saint Peter’s Basilica

and in an

early-4th-century catacomb fresco.

Clement of Alexandria had spoken of Christ driving his chariot

in this way across the sky. The nimbus of the figure under Saint Peter’s

Basilica is described by some as rayed,

as in traditional pre-Christian representations, but another

has said: “Only the cross-shaped nimbus makes the Christian significance

apparent” (emphasis added). Yet another has interpreted the figure as a

representation of the sun with no explicit religious reference whatever, pagan

or Christian.

The traditional image of the sun is used also in Jewish art. A mosaic floor

in Hamat Tiberias

presents

David

as Helios surrounded by a ring with the

signs of the zodiac

.As well as in Hamat Tiberias, figures of

Helios or Sol Invictus also appear in several of the very few surviving schemes

of decoration surviving from Late Antique

synagogues

, including

Beth Alpha

,

Husefah

(Husefa) and

Naaran

, all now in

Israel

. He is shown in floor mosaics, with the

usual radiate halo, and sometimes in a

quadriga

, in the central roundel of a circular

representation of the zodiac or the seasons. These combinations “may have

represented to an agricultural Jewish community the perpetuation of the annual

cycle of the universe or … the central part of a calendar”.

Finally, on Licinius’s death, his memory was branded with infamy; his statues

were thrown down; and by edict, all his laws and judicial proceedings during his

reign were abolished

|

|

|

Frequently Asked d Questions How long until my order is shipped?: shipment of your order after the receipt of payment. How will I know when the order was shipped?: date should be used as a basis of estimating an arrival date. After you shipped the order, how long will the mail take? international shipping times cannot be estimated as they vary from country to country. I am not responsible for any USPS delivery delays, especially for an international package. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? and a Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity, issued by a world-renowned numismatic and antique expert that has identified over 10000 ancient coins and has provided them with the same guarantee. You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Compared to other certification companies, the certificate of authenticity is a $25-50 value. So buy a coin today and own a piece of history, guaranteed. Is there a money back guarantee? I offer a 30 day unconditional money back guarantee. I stand behind my coins and would be willing to exchange your order for either store credit towards other coins, or refund, minus shipping expenses, within 30 days from the receipt of your order. My goal is to have the returning customers for a lifetime, and I am so sure in my coins, their authenticity, numismatic value and beauty, I can offer such a guarantee. Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order?

You can contact me directly via ask seller a question and request my telephone number, or go to my About Me Page to get my contact information only in regards to items purchased on eBay. When should I leave feedback? order, please leave a positive. Please don’t leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. Also, if you sent an email, make sure to check for my reply in your messages before claiming that you didn’t receive a response. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. |