|

Greek Macedonia during the Interregnum

Bronze 17mm (3.40 grams) Miletos or Mylasa Mint, circa 320 B.C.

Reference: Sear 6781 var.; Vecchi 14,413; Liampi, 193-217; Price, 2064

Macedonian shield with Gorgon’s head at center.

Macedonian helmet dividing B – A ; in lower field to left, double-axe; to right,

K.

Following Demetrios’ overthrow by Lysimachos and Pyrrhos,

Macedon underwent a decade during which no ruler was able to control the country

for any length of time. Most of the bronze coins issued in this period were

anonymous, though a few have the name of Pyrrhos in monogrammed form.

Lysimachos also struck some tetradrachms of his usual type at the Amphipolis mint.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

In

Greek mythology

Medusa (Greek:

Μέδουσα (Médousa), “guardian, protectress”)

was a monster

, a

Gorgon

, generally described as having the face

of a hideous human female with living venomous snakes in place of hair. Gazing

directly upon her would turn onlookers to stone. Most sources describe her as

the daughter of Phorcys

and

Ceto, though the author

Hyginus

(Fabulae,

151) interposes a generation and gives Medusa another chthonic pair as parents.

Medusa was beheaded by the hero

Perseus

, who thereafter used her head as a

weapon until he gave it to the goddess

Athena

to place on her

shield

. In

classical antiquity

the image of the head of

Medusa appeared in the

evil-averting device

known as the

Gorgoneion

.

Medusa in

classical mythology

Perseus with the Head of Medusa

,

by

Benvenuto Cellini

, installed 1554

The three Gorgon

sisters—Medusa,

Stheno

, and

Euryale

—were all children of the ancient marine

deities Phorcys

(or Phorkys) and his sister

Ceto (or Keto),

chthonic

monsters from an

archaic

world. Their genealogy is shared with

other sisters, the Graeae

, as in

Aeschylus

‘s

Prometheus Bound

, which places both

trinities of sisters far off “on Kisthene’s dreadful plain”:

Near them their sisters three, the Gorgons, winged

With snakes for hair— hated of mortal man—

While ancient Greek vase-painters and relief carvers imagined Medusa and her

sisters as beings born of monstrous form, sculptors and vase-painters of the

fifth century began to envisage her as being beautiful as well as terrifying. In

an ode written in 490 BC

Pindar

already speaks of “fair-cheeked Medusa”.

In a late version of the Medusa myth, related by the Roman poet

Ovid (Metamorphoses 4.770), Medusa was originally a

ravishingly beautiful maiden, “the jealous aspiration of many suitors,”

priestess in Athena’s temple, but when she was caught being raped by the “Lord

of the Sea” Poseidon

in

Athena

‘s temple, the enraged Athena transformed

Medusa’s beautiful hair to serpents and made her face so terrible to behold that

the mere sight of it would turn onlookers to stone. In Ovid’s telling, Perseus

describes Medusa’s punishment by Minerva (Athena) as just and well earned.

Death

In most versions of the story, she was

beheaded

by the

hero

Perseus

, who was sent to fetch her head by King

Polydectes

of Seriphus. In his conquest, he

received a mirrored shield from

Athena

, gold, winged sandals from

Hermes

, a sword from

Hephaestus

and Hades’ helm of invisibility.

Medusa was the only one of the three Gorgons who was mortal, so Perseus was able

to slay her while looking at the reflection from the mirrored shield he received

from Athena. During that time, Medusa was pregnant by

Poseidon

. When Perseus beheaded her,

Pegasus

, a winged horse, and

Chrysaor

, a golden sword-wielding giant, sprang

from her body.

Head of Medusa, gate of the

Royal Palace of Turin

Jane Ellen Harrison

argues that “her potency

only begins when her head is severed, and that potency resides in the head; she

is in a word a mask with a body later appended… the basis of the

Gorgoneion

is a

cultus object

, a ritual mask misunderstood.”[6]

In the Odyssey

xi,

Homer

does not specifically mention the

Gorgon

Medusa:

Lest for my daring

Persephone

the dread,

From Hades should send up an awful monster’s grisly head.

Harrison’s translation states “the Gorgon was made out of the terror, not the

terror out of the Gorgon.”According to

Ovid, in northwest Africa, Perseus flew past the

Titan

Atlas

, who stood holding the sky aloft, and

transformed him into stone when he tried to attack him. In a similar manner, the

corals

of the

Red Sea

were said to have been formed of

Medusa’s blood spilled onto

seaweed

when Perseus laid down the petrifying

head beside the shore during his short stay in

Ethiopia

where he saved and wed his future

wife, the lovely princess

Andromeda

. Furthermore the poisonous vipers of

the Sahara

, in the

Argonautica

4.1515, Ovid’s

Metamorphoses

4.770 and Lucan’s

Pharsalia

9.820, were said to have grown

from spilt drops of her blood. The blood of Medusa also spawned the

Amphisbaena

(a horned dragon-like creature with

a snake-headed tail).

Perseus then flew to Seriphos, where his mother was about to be forced into

marriage with the king. King Polydectes was turned into stone by the gaze of

Medusa’s head. Then Perseus gave the Gorgon’s head to Athena, who placed it on

her shield, the Aegis

.

Some classical references refer to three Gorgons; Harrison considered that

the tripling of Medusa into a trio of sisters was a secondary feature in the

myth:

The triple form is not primitive, it is merely an instance of a general

tendency… which makes of each woman goddess a trinity, which has given

us the Horae

, the

Charites

, the

Semnai

, and a host of other triple

groups. It is immediately obvious that the Gorgons are not really three

but one + two. The two unslain sisters are mere appendages due to

custom; the real Gorgon is Medusa.

Modern interpretations

Psychoanalysis

An

archaic

Medusa wearing the belt of

the intertwined snakes, a fertility symbol, as depicted on the west

pediment

of the

Artemis Temple in Corfu

, exhibited

at the

Archaeological Museum of Corfu

In 1940,

Sigmund Freud

‘s Das Medusenhaupt (Medusa’s

Head) was published posthumously. This article laid the framework

for his significant contribution to a body of criticism surrounding the monster.

Medusa is presented as “the supreme

talisman

who provides the image of

castration

— associated in the child’s mind

with the discovery of maternal sexuality — and its denial.”

Psychoanalysis

continue

archetypal literary criticism

to the present

day:

Beth Seelig

analyzes Medusa’s punishment from

the aspect of the crime of having been raped rather than having willingly

consented in Athena’s temple as an outcome of the goddess’ unresolved conflicts

with her own father, Zeus

.

Feminism

In the 20th century,

feminists

reassessed Medusa’s appearances in

literature and in modern culture, including the use of Medusa as a

logo by fashion company

Versace

. The name “Medusa” itself is often used

in ways not directly connected to the mythological figure but to suggest the

gorgon’s abilities or to

connote

malevolence; despite her origins as a

beauty, the name in common usage “came to mean monster.” The book Female

Rage: Unlocking Its Secrets, Claiming Its Power by Mary Valentis and Anne

Devane notes that “When we asked women what female rage looks like to them, it

was always Medusa, the snaky-haired monster of myth, who came to mind … In one

interview after another we were told that Medusa is ‘the most horrific woman in

the world’ … [though] none of the women we interviewed could remember the

details of the myth.”[15]

Medusa mosaic (Roman period),

National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Medusa’s visage has since been adopted by many women as a symbol of female

rage; one of the first publications to express this idea was a 1978 issue of

Women: A Journal of Liberation. The cover featured the image of a Gorgon,

which the editors explained “can be a map to guide us through our terrors,

through the depths of our anger into the sources of our power as women.”[15]

In a 1986 article for Women of Power magazine called “Ancient Gorgons: A

Face for Contemporary Women’s Rage,” Emily Erwin Culpepper wrote that “The

Amazon Gorgon face is female fury personified. The Gorgon/Medusa image has been

rapidly adopted by large numbers of feminists who recognize her as one face of

our own rage.”

In Ancient Greece

, the Gorgoneion (Greek:

Γοργόνειον) was originally a horror-creating

apotropaic

pendant

showing the

Gorgon‘s head. It was assimilated by the

Olympian deities

Zeus

and Athena:

both are said to have worn it as a protective

pendant.

It was assumed, among other godlike attributes, as a royal

aegis,

by rulers of the Hellenistic age, as shown, for instance, on the

Alexander Mosaic and the

Gonzaga Cameo.

Homer

refers to the Gorgon on four occasions, each time alluding to the head alone, as

if the creature had no body.

Jane Ellen Harrison

notes that “Medusa is a

head and nothing more…a mask

with a body later appended”. Up to the 5th

century BC, the head was depicted as particularly ugly, with a protruding

tongue,

boar

tusks, puffy cheeks, her eyeballs staring fixedly on the viewer and

the snakes twisting all around her.

The direct frontal stare, “seemingly looking out from its own iconographical

context and directly challenging the viewer”, was highly unusual in ancient

Greek art. In some instances a beard (probably standing for streaks of blood)

was appended to her chin, making her appear as an

orgiastic deity

akin to

Dionysus.

Gorgoneia that decorate the shields of warriors on mid-5th century Greek

vases are considerably less grotesque and menacing. By that time, the Gorgon had

lost her tusks and the snakes were rather stylized. The

Hellenistic

marble known as the

Medusa Rondanini illustrates the Gorgon’s eventual transformation

into a beautiful woman.

Macedonia or Macedon (from

Greek

: Μακεδονία,

Makedonía) was an ancient

kingdom

,

centered in the northeastern part of the

Greek peninsula

[1],

bordered by

Epirus

to the west,

Paionia

to the north, the region of

Thrace

to the

east and Thessaly

to the south. For a brief period, after the conquests of

Alexander the Great

, it became the most powerful state in the world,

controlling a territory that included most of

Greece

and

Persia

, stretching as far as the

Indus

River

; at that time it inaugurated the

Hellenistic period

of

history

.

//

Name

The name Macedonia (Greek:

Μακεδονία,

Makedonía) is related to

the ancient Greek word μακεδνός (Makednos).

It is commonly explained as having originally meant ‘a tall one’ or

‘highlander’, possibly descriptive of the

people

.[2][3]

The shorter English name variant Macedon developed in Middle English,

based on a borrowing from the French form of the name, Macédoine.[4]

History

Early history and

legend

The lands around Aegae, the first Macedonian capital, were home to various

peoples. Macedonia was called Emathia (from king Emathion) and the city of Aiges

was called Edessa, the capital of fabled king Midas. According to legend,

Caranus, accompanied by a multitude of Greeks came to the area in search for a

new homeland

[5]

took Edessa and renamed it to Aegae. Subsequently, he expelled Midas and other

kings off the lands and he formed his new kingdom. According to Herodot, it was

Dorus, the son of Hellen who led his people to Histaeotis, whence they were

driven off by the Cadmeians into Pindus, where they settled as Macedonians.

Later, a branch would migrate further south to be called Dorians

[6]

.

It seems that the first

Macedonian

state emerged in the

8th

or early

7th

century BC

under the

Argead Dynasty

, who, according to legend, migrated to the region from the

Greek city

of

Argos

in

Peloponnesus (thus the name Argead).[7]

It should be mentioned that the Macedonian tribe ruled by the Argeads, was

itself called Argead (which translates as “descended from Argos”).

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers

Haliacmon

and Axius

, called

Lower Macedonia, north of the mountain

Olympus

. Around the time of

Alexander I of Macedon

, the Argead Macedonians started to expand into

Upper Macedonia

, lands inhabited by independent Macedonian tribes like the

Lyncestae and the Elmiotae and to the West, beyond Axius river, into

Eordaia

, Bottiaea

, Mygdonia

, and Almopia

-, regions settled by, among others, many Thracian tribes.[8]

Near the modern city of

Veria

,

Perdiccas I

(or, more likely, his son,

Argaeus I

) built his capital, Aigai (modern

Vergina

).

After a brief period under

Persian

rule under

Darius Hystaspes

, the state regained its independence under King

Alexander II

(495–450

BC).

Macedon during the

Peloponnesian Warr

around 431 BC.

In the long

Peloponnesian War

Macedon was a secondary power that alternated in support

between Sparta and Athens.[9]

Involvement in

the Greek world

Prior to the

4th

century BC

, the kingdom covered a region approximately corresponding to the

province of Macedonia

of modern

Greece

Amyntas III

(c. 393

–370 BC),

though it still retained strong contrasts between the cattle-rich coastal plain

and the fierce isolated tribal hinterland, allied to the king by marriage ties.

They controlled the passes through which barbarian invasions came from

Illyria

to

the north and northwest. It became increasingly

Atticised

during this period, though prominent

Athenians

appear to have regarded the Macedonians as uncouth.[10]

Before the establishment of the

League of Corinth

, even though the Macedonians apparently spoke a dialect of

the Greek language and claimed proudly that they were Greeks, they were not

considered to fully share the

classical Greek

culture by many of the inhabitants of the southern city

states, because they did not share the

polis

based style

of government of the southerners.[9]

Herodotus

,

being one of the foremost biographer in antiquity who lived in Greece at the

time when the Macedonian king

Alexander I

was in power, mentioned: “I happen to know, and I will

demonstrate in a subsequent chapter of this history, that these descendants of

Perdiccas are, as they themselves claim, of Greek nationality. This was,

moreover, recognized by the managers of the

Olympic games

, on the occasion when

Alexander

wished to compete and his Greek competitors tried to exclude him

on the ground that foreigners were not allowed to take part. Alexander, however,

proved his Argive descent, and so was accepted as a Greek and allowed to enter

for the foot-race. He came in equal first”..[11]

Over the 4th century Macedon became more politically involved with the

south-central city-states of

Ancient GreecePella

, resembling

Mycenaean

culture more than classic

Hellenic

city-states, and other archaic customs, like Philip’s multiple

wives in addition to his Epirote queen

Olympias

,

mother of Alexander.

Another archaic remnant was the very persistence of a

hereditary

monarchy

which wielded formidable – sometimes absolute – power, although

this was at times checked by the landed aristocracy, and often disturbed by

power struggles within the royal family itself. This contrasted sharply with the

Greek cultures further south, where the ubiquitous city-states mostly possessed

aristocratic or democratic institutions; the

de facto

monarchy of tyrants

,

in which heredity was usually more of an ambition rather than the accepted rule;

and the limited, predominantly military and sacerdotal, power of the twin

hereditary Spartan

kings. The same might have held true of

feudal

institutions like

serfdom

,

which may have persisted in Macedon well into historical times. Such

institutions were abolished by city-states well before Macedon’s rise (most

notably by the Athenian legislator

Solon

‘s famous

σεισάχθεια

seisachtheia

laws)..

Amyntas had three sons; the first two,

Alexander II

and

Perdiccas III

reigned only briefly. Perdiccas III’s infant heir was deposed

by Amyntas’ third son,

Philip II of Macedon

, who made himself king and ushered in a period of

Macedonian dominance of Greece. Under Philip II, (359–336

BC), Macedon expanded into the territory of the

Paionians

,

Thracians

,

and Illyrians

.

Among other conquests, he annexed the regions of

Pelagonia

and Southern

Paionia

.[12]]

Kingdom of Macedon after Philip’s II death.

Philip redesigned the

army of Macedon

adding a number of variations to the traditional

hoplite

hetairoi

, a well armoured heavy cavalry, and more light infantry, both

of which added greater flexibility and responsiveness to the force. He also

lengthened the spear and shrank the shield of the main infantry force,

increasing its offensive capabilities.

Philip began to rapidly expand the borders of his kingdom. He first

campaigned in the north against non-Greek peoples such as the

IllyriansAmphipolis

,

which controlled the way into

Thracee

and also

was near valuable silver mines. This region had been part of the

Athenian Empire

, and Athens still considered it as in their sphere. The

Athenians attempted to curb the growing power of Macedonia, but were limited by

the outbreak of the

Social War

. They could also do little to halt Philip when he turned his

armies south and took over most of

Thessaly

.

Control of Thessaly meant Philip was now closely involved in the politics of

central Greece. 356 BCE saw the outbreak of the

Third Sacred War

that pitted

Phocis

against

Thebes

and its allies. Thebes recruited the Macedonians to join them and at

the

Battle of Crocus Field

Phillip decisively defeated Phocis and its Athenian

allies. As a result Macedonia became the leading state in the

Amphictyonic League

and Phillip became head of the Pythian Games, firmly

putting the Macedonian leader at the centre of the Greek political world.

In the continuing conflict with Athens Philip marched east through Thrace in

an attempt to capture

Byzantium

and the Bosphorus

, thus cutting off the Black Sea grain supply that provided Athens

with much of its food. The siege of Byzantium failed, but Athens realized the

grave danger the rise of Macedon presented and under

Demosthenes

built a coalition of many of the major states to oppose the

Macedonians. Most importantly Thebes, which had the strongest ground force of

any of the city states, joined the effort. The allies met the Macedonians at the

Battle of Chaeronea

and were decisively defeated, leaving Philip and the

Macedonians the unquestioned master of Greece.

Empire

Further information:

Conquests of Alexander the Great

, Wars

of the Diadochi, Seleucid

Empire, and Diadochi

Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion

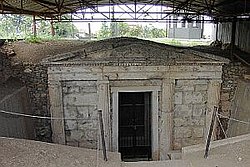

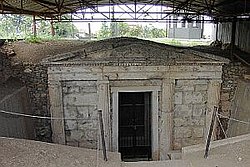

The entrance to one of the royal tombs at Vergina, a UNESCO World

Heritage site.

Philip’s son,

Alexander the Great

(356–323

BC), managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the central

Greek city-states, but also to the

Persian empire

, including

Egypt

and lands

as far east as the fringes of

India

. Alexander’s adoption of the styles of government of the conquered

territories was accompanied by the spread of Greek culture and learning through

his vast empire. Although the empire fractured into multiple Hellenic regimes

shortly after his death, his conquests left a lasting legacy, not least in the

new Greek-speaking cities founded across Persia’s western territories, heralding

the

Hellenistic

Diadochi,

Macedonia fell to the

Antipatrid dynasty

, which was overthrown by the

Antigonid dynasty

after only a few years, in 294 BC..

Hellenistic era

Antipater

and his son Cassander

gained control of Macedonia but it slid into a long period of

civil strife following Cassander’s death in

297 BC

. It was

ruled for a while by

Demetrius I

(294–288

BC) but fell into civil war.

Demetrius’ son,

Antigonus II

(277–239

BC), defeated a

Galatian

invasion as a

condottiere

, and regained his family’s position in Macedonia; he

successfully restored order and prosperity there, though he lost control of many

of the Greek city-states. He established a stable monarchy under the

Antigonid dynasty

.

Antigonus III

((239–221

BC) built on these gains by re-establishing Macedonian power across the

region.

What is notable about the Macedonian regime during the Hellenistic times is

that it was the only successor state to the Empire that maintained the old

archaic perception of Kingship, and never adopted the ways of the Hellenistic

Monarchy. Thus the king was never deified in the same way that Ptolemies and

Seleucids were in Egypt and Asia respectively, and never adopted the custom of

Proskynesis

. The ancient Macedonians during the Hellenistic times were still

addressing their kings in a far more casual way than the subjects of the rest of

the Diadochi, and the Kings were still consulting with their aristocracy

(Philoi) in the process of making their decisions.

Conflict with Rome

Kingdom of Macedon under Philip V.

Under

Philip V of Macedon

(221–179

BC

Perseus of Macedon (179–168

BC), the kingdom clashed with the rising power of the

Roman Republic

. During the

2nd

and 1st centuries BC

, Macedon fought a

series of wars

with Rome. Two major losses that led to their inevitable

defeat were in 197

BC

when Rome defeated Philip V, and

168 BC

when

Rome defeated Perseus. The overall losses resulted in the defeat of Macedon, the

deposition of the Antigonid dynasty and the dismantling of the Macedonian

kingdom. Andriscus

‘ brief success at reestablishing the monarchy in

149 BCC

was

quickly followed by his defeat the following year and the establishment of

direct

Roman

rule and the organization of Macedon as the

Roman province of Macedonia

.

Institutions

éthnē), and between the two, the districts. The

study of these different institutions has been considerably renewed thanks to

epigraphy

,

which has given us the possibility to reread the indications given us by ancient

literary sources such as

Livy and

Polybius

.

They show that the Macedonian institutions were near to those of the Greek

federal states, like the

Aetolian

and

Achaeann

leagues, whose unity was reinforced by the presence of the king.

The

Vergina Sun

, the 16-ray star covering what appears to be the

royal burial larnax of Philip II of Macedon, discovered in Vergina,

Greece.

The King

The king<!– (

Βασιλεύς,

Basileús) headed the

central administration: he led the kingdom from its capital, Pella, and in his

royal palace was conserved the state’s archive. He was helped in carrying out

his work by the Royal Secretary (βασιλικὸς

γραμματεύς, basilikós

grammateús), whose work was of primary importance, and by the

Council

.

The king was commander of the army, head of the Macedonian religion, and

director of diplomacy. Also, only he could conclude treaties, and, until

Philip V

, mint coins.

The number of civil servants was limited: the king directed his kingdom

mostly in an indirect way, supporting himself principally through the local

magistrates, the epistates, with whom he constantly kept in touch.

Successionon

Royal succession in Macedon was hereditary, male,

patrilineal

and generally respected the principle of

primogeniture

. There was also an elective element: when the king died, his

designated heir, generally but not always the eldest son, had first to be

accepted by the council and then presented to the general Assembly to be

acclaimed king and obtain the oath of fidelity.

Perdiccas III, slain by the

Illyrians

,

Philip II

assassinated by

Pausanias of Orestis

,

Alexander the Great

, suddenly died of malady, etc. Succession crises were

frequent, especially up to the

4th

century BC

, when the magnate families of Upper Macedonia still cultivated

the ambition of overthrowing the Argaead dynasty and to ascend to the throne.

An atrium with a pebble-mosaic paving, in Pella, Greece

Financesces

The king was the simple guardian and administrator of the treasure of Macedon

and of the king’s incomes (βασιλικά,

basiliká), which belonged

to the Macedonians: and the tributes that came to the kingdom thanks to the

treaties with the defeated people also went to the Macedonian people, and not to

the king. Even if the king was not accountable for his management of the

kingdom’s entries, he may have felt responsible to defend his administration on

certain occasions: Arrian

tells us that during the

mutiny

of

Alexander’s soldiers at Opis

in 324 BC BC

,

Alexander detailed the possessions of his father at his death to prove he had

not abused his charge.

It is known from Livy and Polybius that the basiliká included the

following sources of income:

- The mines of gold and silver (for example those of the

Pangaeus

), which were the exclusive possession of the king, and which

permitted him to strike currency, as already said his sole privilege till

Philip V, who conceded to cities and districts the right of coinage for the

lesser denominations, like bronze.

- The forests, whose timber was very appreciated by the Greek

cities to build their ships: in particular, it is known that

Athens

made

commercial treaties with Macedon in the

5th century BC

to import the timber necessary for the construction and

the maintenance of its fleet of war.

- The royal landed properties, lands that were annexed to the royal

domain through conquest, and that the king exploited either directly, in

particular through servile workforce made up of prisoners of war, or

indirectly through a leasing system.

- The port duties on commerce (importation and exportation taxes).

The most common way to exploit these different sources of income was by

leasing: the Pseudo-Aristotle

reports in the

Oeconomica

that

Amyntas III

(or maybe Philip II) doubled the kingdom’s port revenues with

the help of

Callistratus

, who had taken refuge in Macedon, bringing them from 20 to 40

talents

per year. To do this, the exploitation of the harbour taxes was

given every year at the private offering the highest bidding. It is also known

from Livy that the mines and the forests were leased for a fixed sum under

Philip V, and it appears that the same happened under the Argaead dynasty: from

here possibly comes the leasing system that was used in

Ptolemaic Egypt

.

Except for the king’s properties, land in Macedon was free: Macedonians were

free men and did not pay land taxes on private grounds. Even extraordinary taxes

like those paid by the Athenians in times of war did not exist. Even in

conditions of economic peril, like what happened to Alexander in

334 BC< and

Perseus in

168 BC

,

the monarchy did not tax its subjects but raised funds through loans, first of

all by his Companions, or raised the cost of the leases.

The king could grant the atelíē (ἀτελίη),

a privilege of tax exemption, as Alexander did with those Macedonian families

which had losses in the

battle of the Granicus

in May

334334

: they were

exempted from paying tribute for leasing royal grounds and commercial taxes.

Extraordinary incomes came from the spoils of war, which were divided between

the king and his men. At the time of Philip II and Alexander, this was a

considerable source of income. A considerable part of the gold and silver

objects taken at the time of the European and Asian campaigns were melted in

ingots and then sent to the monetary foundries of

Pella

Amphipolis,

most active of the kingdom at that time: an estimate judges that during the

reign of Alexander only the mint of Amphipolis struck about 13 million silver

tetradrachms

.

The Assembly

All the kingdom’s citizen-soldiers gather in a popular assembly, which is

held at least twice a year, in spring and in autumn, with the opening and the

closing of the campaigning season.

This assembly (koinê ekklesia

or koinon makedonôn), of

the army in times of war, of the people in times of peace, is called by the king

and plays a significant role through the acclamation of the kings and in capital

trials; it can be consulted (without obligation) for the foreign politics

(declarations of war, treaties) and for the appointment of high state officials.

In the majority of these occasions, the Assembly does nothing but ratify the

proposals of a smaller body, the Council. It is also the Assembly which votes

the honors, sends embassies, during its two annual meetings. It was abolished by

the Romans

at the time of their reorganization of Macedonia in

167 BC

, to

prevent, according to Livy

, that a demagogue could make use of it as a mean to revolt against

their authority.

The Friends (philoi)

or the king’s Companions (basilikoi

hetairoi

) were named for life by the king among the Macedonian

aristocracy.cy.

The most important generals of the army (hégémones tôn taxéôn),

also named by the king.

The king had in reality less power in the choice of the members of the

Council than appearances would warrant; this was because many of the kingdom’s

most important noblemen were members of the Council by birth-right.

The Council primarily exerted a probouleutic function with respect to the

Assembly: it prepared and proposed the decisions which the Assembly would have

discussed and voted, working in many fields such as the designation of kings and

regents, as of that of the high administrators and the declarations of war. It

was also the first and final authority for all the cases which did not involve

capital punishment.

The Council gathered frequently and represented the principal body of

government of the kingdom. Any important decision taken by the king was

subjected before it for deliberation.on.

Inside the Council ruled the democratic principles of iségoria

(equality of word) and of parrhésia (freedom of speech), to which even

the king subjected himself.

After the removal of the

Antigonid dynasty

by the Romans in

167 BC

, it is

possible that the synedrion remained, unlike the Assembly, representing the sole

federal authority in Macedonia after the country’s division in four merides.

Regional

districts (Merides)

The creation of an intermediate territorial administrative level between the

central government and the cities should probably be attributed to Philip II:

this reform corresponded with the need to adapt the kingdom’s institutions to

the great expansion of Macedon under his rule. It was no longer practical to

convene all the Macedonians in a single general assembly, and the answer to this

problem was the creation of four regional districts, each with a regional

assembly. These territorial divisions clearly did not follow any historical or

traditional internal divisions; they were simply artificial administrative

lines.

This said, it should be noted that the existence of these districts is not

attested with certainty (by

numismatics

) before the beginning of the

2nd

century BC

.

|