|

Roman Fascinus Phallic Amulet from circa 200 B.C. – 100 A.D.

Bronze measuring

27mm x 44mm and weighs 8.70 grams

Provenance: From private collection in the United States of America.

Ownership History: From private collection in the United States, bought

in private sale in the United States of America.

This kind of phallic amulet jewelry was worn in ancient Greek and Roman times to ward off the Evil Eye. Roman myths, such as the begetting of Servius Tullius, suggest that this phallus was an embodiment of a masculine generative power located within the hearth, regarded as sacred. The fascinus was thought particularly to ward off evil from children, mainly boys, and from conquering generals. Intriguing authentic ancient Roman artifact.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

In ancient Roman religion and magic, the fascinus or fascinum was the embodiment of the divine phallus. The word can refer to the deity himself (Fascinus), to phallus effigies and amulets, and to the spells used to invoke his divine protection. Pliny calls it a medicus invidiae, a “doctor” or remedy for envy (invidia, a “looking upon”) or the evil eye.

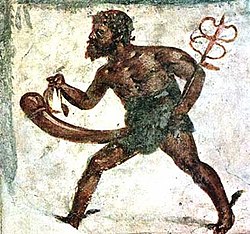

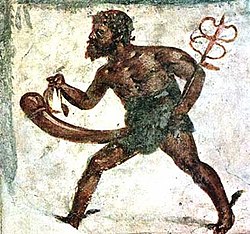

A graphic representation of the power of the fascinus to ward off the evil eye is found on a Roman mosaic that depicts a phallus ejaculating into a disembodied eye; a 1st-century BC terracotta figurine shows “two little phallus-men sawing an eyeball in half.” As a divinized phallus, the fascinus shared attributes with Mutunus Tutunus, whose shrine was supposed to date from the founding of the city, and the imported Greek god Priapus.

The Vestal Virgins tended the cult of the fascinus populi Romani, the sacred image of the phallus that was one of the tokens of the safety of the state. It was thus associated with the Palladium. Roman myths, such as the begetting of Servius Tullius, suggest that this phallus was an embodiment of a masculine generative power located within the hearth, regarded as sacred. Augustine, whose primary source on Roman religion was the lost theological works of Varro, notes that a phallic image was carried in procession annually at the festival of Father Liber, the Roman god identified with Dionysus or Bacchus, for the purpose of protecting the fields from fascinatio, magic compulsion:

| “ |

Varro says that certain rites of Liber were celebrated in Italy which were of such unrestrained wickedness that the shameful parts of the male were worshipped at crossroads in his honour. … For, during the days of the festival of Liber, this obscene member, placed on a little trolley, was first exhibited with great honour at the crossroads in the countryside, and then conveyed into the city itself. … In this way, it seems, the god Liber was to be propitiated, in order to secure the growth of seeds and to repel enchantment (fascinatio) from the fields. |

” |

Phallic charms, often winged, were ubiquitous in Roman culture, from jewelry to bells and windchimes to lamps. The fascinus was thought particularly to ward off evil from children, mainly boys, and from conquering generals. Pliny notes the custom of hanging a phallic charm on a baby’s neck, and examples have been found of phallus-bearing rings too small to be worn except by children. When a general celebrated a triumph, the Vestals hung an effigy of the fascinus on the underside of his chariot to protect him from invidia.

The “fist and phallus” amulet was prevalent amongst soldiers. These are phallic pendants with a representation of a (usually) clenched fist at the bottom of the shaft, facing away from the glans. Several examples show the fist making the manus fica or “fig sign”, a symbol of good luck. The largest known collection comes from Camulodunum.

The English word “fascinate” ultimately derives from Latin fascinum and the related verb fascinare, “to use the power of the fascinus,” that is, “to practice magic” and hence “to enchant, bewitch.” Catullus uses the verb at the end of Carmen 7, a hendecasyllabic poem addressing his lover Lesbia; he expresses his infinite desire for kisses that cannot be counted by voyeurs nor “fascinated” (put under a spell) by a malicious tongue; such bliss, as also in Carmen 5, potentially attracts invidia.

Fescennine verses, the satiric and often lewd songs or chants performed on various social occasions, may have been so-named from the fascinum; ancient sources propose this etymology along with an alternative origin from Fescennia, a small town in Etruria.

A phallus is a penis, especially when erect, an object that resembles a penis, or a mimetic image of an erect penis.

Any object that symbolically — or, more precisely, iconically — resembles a penis may also be referred to as a phallus; however, such objects are more often referred to as being phallic (as in “phallic symbol“). Such symbols often represent fertility and cultural implications that are associated with the male sexual organ, as well as the male orgasm.

Polyphallic wind chime from Pompeii; a bell hung from each phallus

|