|

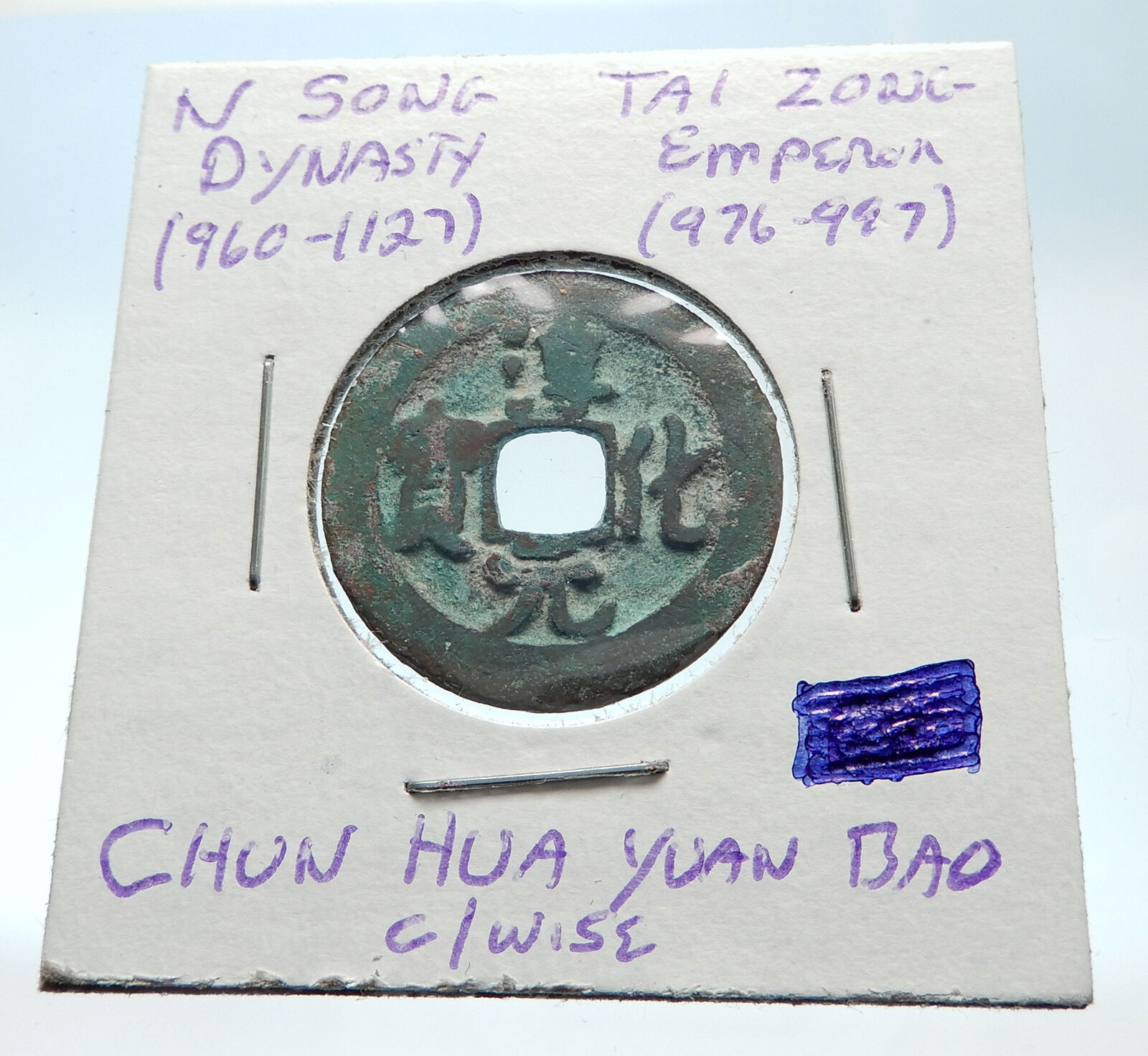

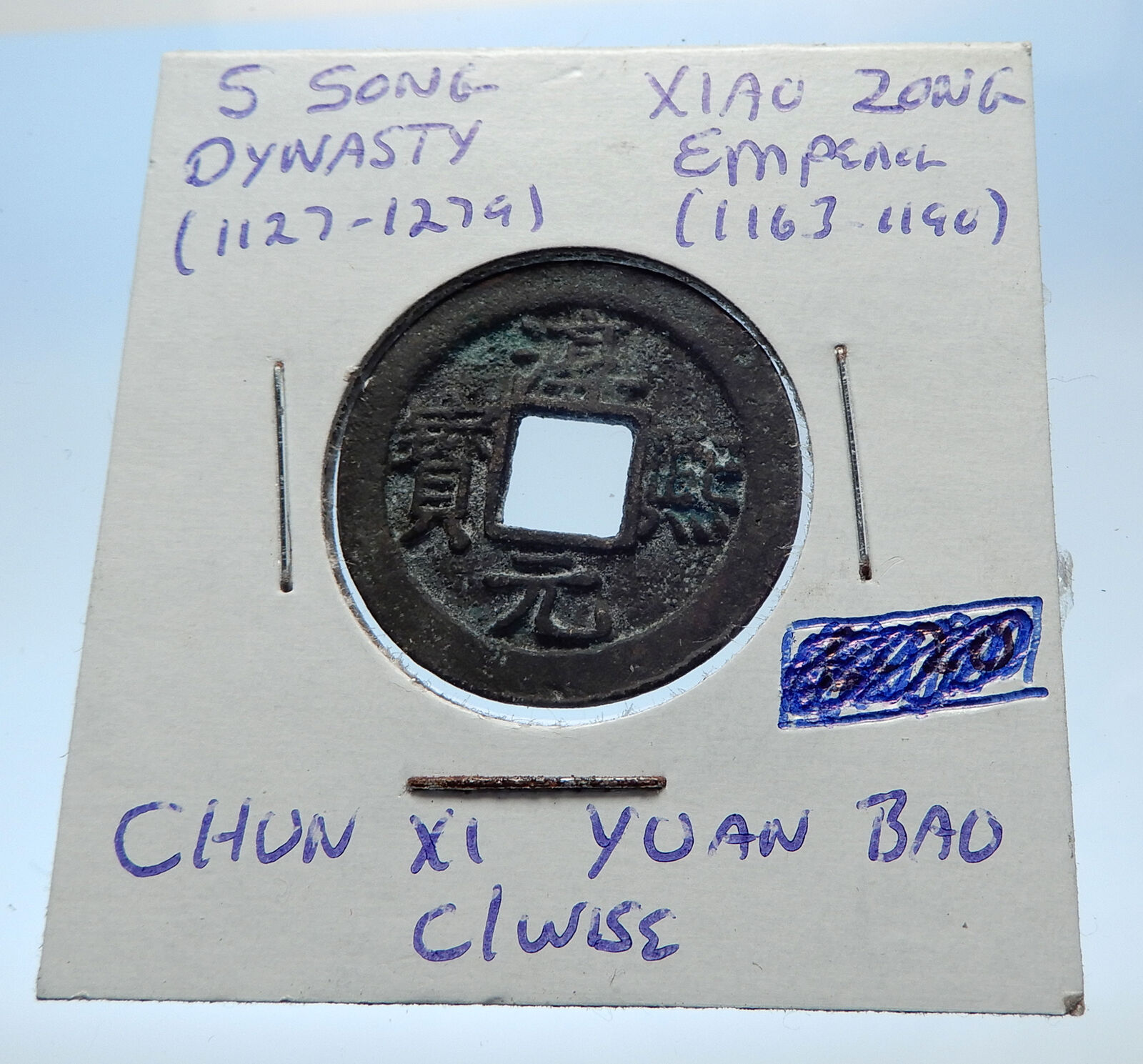

China – Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127 A.D.)

Hui Zong – Emperor: 1101-1125 A.D.

Cash 33mm

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Emperor Huizong of Song (7 June 1082 – 4 June 1135), personal name Zhao Ji, was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty in China. He was also a very well-known calligrapher. Born as the 11th son of Emperor Shenzong, he ascended the throne in 1100 upon the death of his elder brother and predecessor, Emperor Zhezong, because Emperor Zhezong’s only son died prematurely. He lived in luxury, sophistication and art in the first half of his life. In 1126, when the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty invaded the Song dynasty during the Jin-Song Wars, Emperor Huizong abdicated and passed on his throne to his eldest son, Emperor Qinzong , while he assumed the honorary title of Taishang Huang (or “Retired Emperor”). The following year, the Song capital, Bianjing, was conquered by Jin forces in an event historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Emperor Huizong, along with Emperor Qinzong and the rest of their family, were taken captive by the Jurchens and brought back to the Jin capital, Huining Prefecture in 1128. The Jurchen ruler, Emperor Taizong of Jin, gave the former Emperor Huizong a title, Duke Hunde (literally “Besotted Duke”), to humiliate him. After his surviving son, Zhao Gou, declared himself as the dynasty’s tenth emperor as Emperor Gaozong, the Jurchens used him, Qinzong, and other imperial family members to put pressure on Gaozong and his court to surrender. Emperor Huizong died in Wuguo after spending about nine years in captivity. Emperor Huizong of Song (7 June 1082 – 4 June 1135), personal name Zhao Ji, was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty in China. He was also a very well-known calligrapher. Born as the 11th son of Emperor Shenzong, he ascended the throne in 1100 upon the death of his elder brother and predecessor, Emperor Zhezong, because Emperor Zhezong’s only son died prematurely. He lived in luxury, sophistication and art in the first half of his life. In 1126, when the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty invaded the Song dynasty during the Jin-Song Wars, Emperor Huizong abdicated and passed on his throne to his eldest son, Emperor Qinzong , while he assumed the honorary title of Taishang Huang (or “Retired Emperor”). The following year, the Song capital, Bianjing, was conquered by Jin forces in an event historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Emperor Huizong, along with Emperor Qinzong and the rest of their family, were taken captive by the Jurchens and brought back to the Jin capital, Huining Prefecture in 1128. The Jurchen ruler, Emperor Taizong of Jin, gave the former Emperor Huizong a title, Duke Hunde (literally “Besotted Duke”), to humiliate him. After his surviving son, Zhao Gou, declared himself as the dynasty’s tenth emperor as Emperor Gaozong, the Jurchens used him, Qinzong, and other imperial family members to put pressure on Gaozong and his court to surrender. Emperor Huizong died in Wuguo after spending about nine years in captivity.

Despite his incompetence in rulership, Emperor Huizong was known for his promotion of Taoism and talents in poetry, painting, calligraphy and music. He sponsored numerous artists at his imperial court, and the catalogue of his collection listed over 6,000 known paintings.

Cash was a type of coin of China and East Asia, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD. Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China as well as under Mongol, and Manchu rule. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast but, during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century.

In the modern era, these coins are considered to be Chinese “good luck coins”; they are hung on strings and round the necks of children, or over the beds of sick people. They hold a place in various superstitions, as well as Traditional Chinese medicine, and Feng shui. Currencies based on the Chinese cash coins include the Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn.

The Northern Song Dynasty(4 February, 960 – 20 March, 1127) is an era during the Song Dynasty. It came to an end when its capital city, the city of Kaifeng, was conquered by enemies from the north. Later, the provisional capital of the Northern Song Dynasty was founded in Ying Tian Fu (present-day Shangqiu of Henan). Historically, the Song Dynasty include both the Northern and the Southern Song. It is named “Northern” to distinguish from the “Southern”, which resided mainly in Southern China. Emperor Taizu of Song elaborated a mutiny and usurped the throne of the Later Zhou (the last in a succession of five dynasties), which marked the beginning of the Dynasty. In 1127, its capital city Kaifeng fell into the hand of the state of Jin, during which time the emperor and his family all fell captive. The Northern Song came to its end the next year. It was ruled by nine emperors, and lasted for 127 years.

The ruled area of the Northern Song extended to the southeastern coast. Its Northern Border with the Liao state was the Hai River, Ba Zhou city, Hebei province, and Yanmen Pass, Shanxi (Jin) province, an essential pass of the Great wall. Its reign reached northwest to the Hengshan Mountain in Shaanxi (Shan/Qin), the east of Gansu province, and the Huangshui River of Qinghai, all the way to the border with the state of Liao. In the west, it shared the boundary line of Min Mountains and Dadu River (Sichuan) with Tibet and Dali Kingdom. It was also adjacent with Vietnam across Guangxi province. Still, the Northern Song Dynasty had been the smallest in terms of land area among all the united empires that were established on the vast Central Plains. As was recorded by Taiping Huanyu Ji, the population of the Northern Song Dynasty exploded from 32,500,000 in 980 C.E. to 100,001,200 in 1110 C.E..

The founding

Taizu, the first emperor of Song, Zhao Kuang Yin was a professional soldier. He was a Lifeguard in charge of the troops in front of the emperor’s palace in the Later Zhou. Zhao had become an essential military figure during the reign of emperor Shizong owing to his outstanding military exploits. After Shizong died, the young Gongdi emperor ascended the throne. Zhao later seized power through the Chenqiao Mutiny, and established the Song. He adopted an authoritarian centralized system to uproot the potential dictatorship and autocracy of senior officials, which had long been a threat ever since the mid-Tang Dynasty, and to solidify the authoritarian central government, a contributing factor to the stability and growth of the feudal social economy. On the other hand, the redundant bureaucracy and unnecessary official posts led to a terrible decline in efficiency and subsequently financial difficulties.

In the field of military, the Northern Song expanded troops, weakened the military power of generals by separating the power to different persons, and shortened their service term at one official post so that they would not have the chance to accumulate that much power before it threatened the central. The constant change of the general, however, resulted in the decline of fighting capacity of the soldiers, and the Northern Song troops had suffered repeated defeats against minority groups like the Liao and Western Xia. The frontier defense thus became empty and feeble, which was detrimental to national security. Overall, the authoritarian centralized system had to some extents contributed to the unification and stability of the feudal state, preventing the local separatism and peasant revolts from happening, but it also foreshadowed the deepening impoverished and enfeebled from the mid Northern Song.

During the spring festival in 960, Zhao’s partisan fellows made up false intelligence that the Liao state was to invade. The prime minister (in feudal China) then immediately commanded Zhao to go to the frontier to defend. On the third day of the first lunar month, Zhao arrived at Chenqiao, and was draped with the imperial yellow robe by his supporters (a ritual of admitting someone as the emperor, kind of like coronation) that night. The officials of the later Zhou deemed it as irreversible and did nothing but accepted the reality. The Gondi of later Zhou was forced to leave the throne, and Zhao subsequently became the Taizu of the Song dynasty.

In 961 and 969, during banquets, and while drunken (or pretended to be) Zhao threatened the generals for twice not to rebel against the Song just like he himself had done against the later Zhou, and deprived them of the power they used to have by assigning them to merely nominal positions while appointing civil officials as commanders in troops, to centralize the military power. The Northern Song dynasty was thus free from local military separatists, but at the same time the local resources were limited. It all led to its defeats in battles against the northern tribes.。

|

Emperor Huizong of Song (7 June 1082 – 4 June 1135), personal name Zhao Ji, was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty in China. He was also a very well-known calligrapher. Born as the 11th son of Emperor Shenzong, he ascended the throne in 1100 upon the death of his elder brother and predecessor, Emperor Zhezong, because Emperor Zhezong’s only son died prematurely. He lived in luxury, sophistication and art in the first half of his life. In 1126, when the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty invaded the Song dynasty during the Jin-Song Wars, Emperor Huizong abdicated and passed on his throne to his eldest son, Emperor Qinzong , while he assumed the honorary title of Taishang Huang (or “Retired Emperor”). The following year, the Song capital, Bianjing, was conquered by Jin forces in an event historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Emperor Huizong, along with Emperor Qinzong and the rest of their family, were taken captive by the Jurchens and brought back to the Jin capital, Huining Prefecture in 1128. The Jurchen ruler, Emperor Taizong of Jin, gave the former Emperor Huizong a title, Duke Hunde (literally “Besotted Duke”), to humiliate him. After his surviving son, Zhao Gou, declared himself as the dynasty’s tenth emperor as Emperor Gaozong, the Jurchens used him, Qinzong, and other imperial family members to put pressure on Gaozong and his court to surrender. Emperor Huizong died in Wuguo after spending about nine years in captivity.

Emperor Huizong of Song (7 June 1082 – 4 June 1135), personal name Zhao Ji, was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty in China. He was also a very well-known calligrapher. Born as the 11th son of Emperor Shenzong, he ascended the throne in 1100 upon the death of his elder brother and predecessor, Emperor Zhezong, because Emperor Zhezong’s only son died prematurely. He lived in luxury, sophistication and art in the first half of his life. In 1126, when the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty invaded the Song dynasty during the Jin-Song Wars, Emperor Huizong abdicated and passed on his throne to his eldest son, Emperor Qinzong , while he assumed the honorary title of Taishang Huang (or “Retired Emperor”). The following year, the Song capital, Bianjing, was conquered by Jin forces in an event historically known as the Jingkang Incident. Emperor Huizong, along with Emperor Qinzong and the rest of their family, were taken captive by the Jurchens and brought back to the Jin capital, Huining Prefecture in 1128. The Jurchen ruler, Emperor Taizong of Jin, gave the former Emperor Huizong a title, Duke Hunde (literally “Besotted Duke”), to humiliate him. After his surviving son, Zhao Gou, declared himself as the dynasty’s tenth emperor as Emperor Gaozong, the Jurchens used him, Qinzong, and other imperial family members to put pressure on Gaozong and his court to surrender. Emperor Huizong died in Wuguo after spending about nine years in captivity.