|

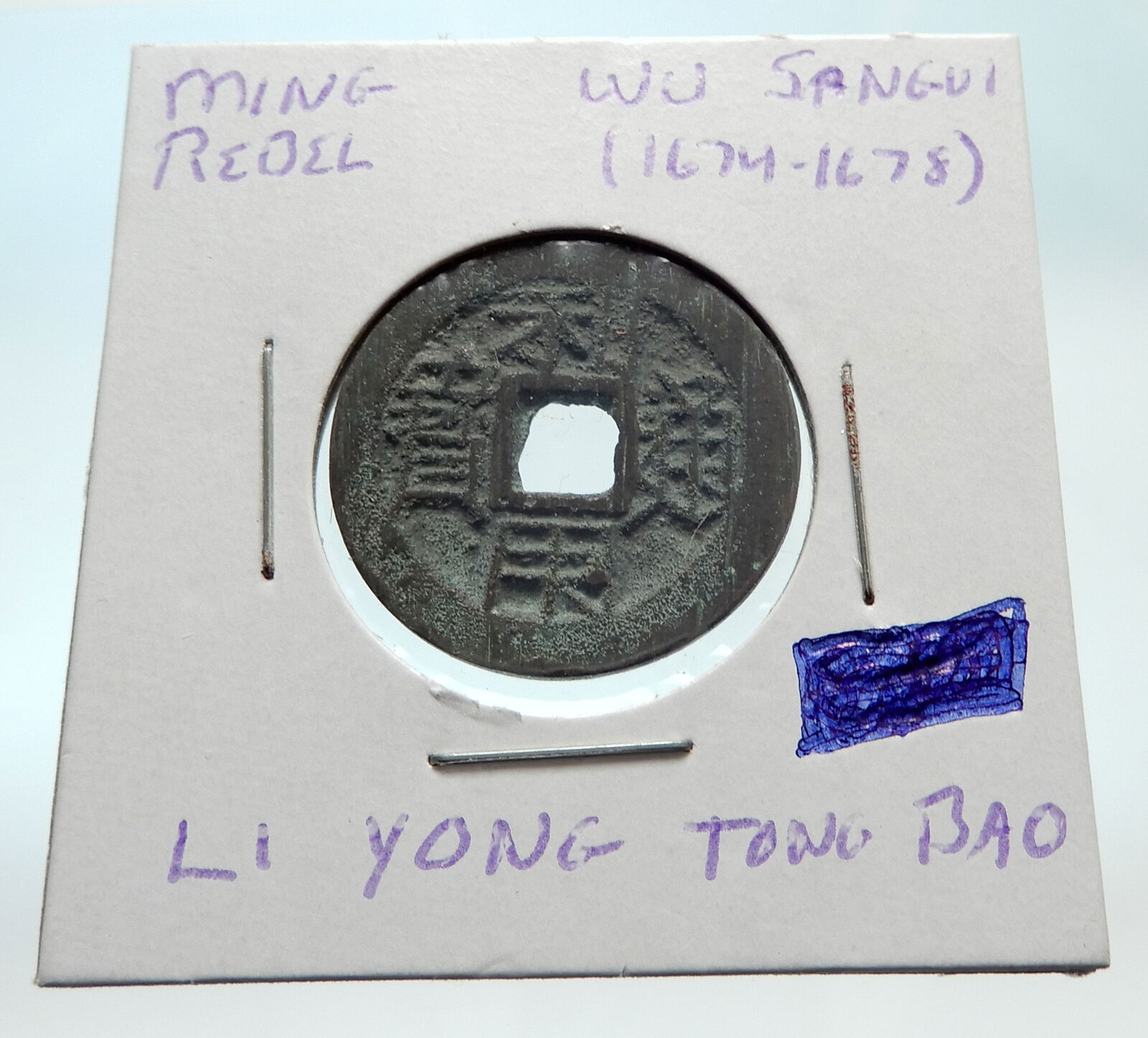

China – Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 A.D.) – Pre-Ming

Zhu Yuanzhang – Prince of Wu: 1361-1368 A.D.

Bronze Da Zong Tong Bao 2 Cash 42mm, Struck 1361-1368 AD

Reference: H# 20.22

Four Chinese characters, square hole within.

Zhe above: Zhejian province mint.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328 – 24 June 1398), personal name Zhu Yuanzhang (Chinese: 朱元璋; Wade–Giles: Chu Yuan-chang), courtesy name Guorui (simplified Chinese: 国瑞; traditional Chinese: 國瑞), was the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1368 to 1398.

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts increased across China in the 14th century, Zhu Yuanzhang rose to command the forces that conquered China, ending the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and forcing the Mongols to retreat to the Eurasian Steppe. Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and established the Ming dynasty at the beginning of 1368 and occupied the Yuan capital, Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing), with his army that same year. Trusting only his family, he made his many sons feudal princes along the northern marches and the Yangtze valley. Having outlived his eldest son Zhu Biao, Zhu enthroned Zhu Biao’s son via a series of instructions. This ended in failure when the Jianwen Emperor’s attempts to unseat his uncles led to the Jingnan Rebellion. As famine, plagues and peasant revolts increased across China in the 14th century, Zhu Yuanzhang rose to command the forces that conquered China, ending the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and forcing the Mongols to retreat to the Eurasian Steppe. Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and established the Ming dynasty at the beginning of 1368 and occupied the Yuan capital, Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing), with his army that same year. Trusting only his family, he made his many sons feudal princes along the northern marches and the Yangtze valley. Having outlived his eldest son Zhu Biao, Zhu enthroned Zhu Biao’s son via a series of instructions. This ended in failure when the Jianwen Emperor’s attempts to unseat his uncles led to the Jingnan Rebellion.

The era of Hongwu was noted for its tolerance of minorities and religions; Ma Zhou, the Chinese historian indicates that the Hongwu ordered the renovation and construction of many mosques in Xi’an and Nanjing. Wang Daiyu also recorded that the emperor wrote 100 characters praising Islam, Baizi zan.

The reign of the Hongwu Emperor is notable for his unprecedented political reforms. The emperor abolished the position of chancellor, drastically reduced the role of court eunuchs, and adopted draconian measures to address corruption. He also established the Embroidered Uniform Guard, one of the best known secret police organizations in imperial China. In the 1380s and 1390s a series of purges were launched to eliminate his high-ranked officials and generals; tens of thousands were executed. The reign of Hongwu also witnessed much cruelty. Various cruel methods of execution was introduced for punishable crimes and for those who directly criticized the emperor, and massacres were also carried out against everyone who resisted his rule.

The emperor encouraged agriculture, reduced taxes, incentivized the cultivation of new land, and established laws protecting peasants’ property. He also confiscated land held by large estates and forbade private slavery. At the same time, he banned free movement in the empire and assigned hereditary occupational categories to households. Through these measures, Zhu Yuanzhang attempted to rebuild a country that had been ravaged by war, limit and control its social groups, and instill orthodox values in his subjects, eventually creating a strictly regimented society of self-sufficient farming communities.

The Ming dynasty was the ruling dynasty of China – then known as the Great Ming Empire – for 276 years (1368-1644) following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last imperial dynasty in China ruled by ethnic Han Chinese. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng (who established the Shun dynasty, soon replaced by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty), regimes loyal to the Ming throne – collectively called the Southern Ming – survived until 1683.

.svg/280px-Ming_Empire_cca_1580_(en).svg.png)

Ming China around 1580

The Hongwu Emperor (ruled 1368-98) attempted to create a society of self-sufficient rural communities ordered in a rigid, immobile system that would guarantee and support a permanent class of soldiers for his dynasty: the empire’s standing army exceeded one million troops and the navy’s dockyards in Nanjing were the largest in the world. He also took great care breaking the power of the court eunuchs[6] and unrelated magnates, enfeoffing his many sons throughout China and attempting to guide these princes through the Huang-Ming Zuxun, a set of published dynastic instructions. This failed spectacularly when his teenage successor, the Jianwen Emperor, attempted to curtail his uncles’ power, prompting the Jingnan Campaign, an uprising that placed the Prince of Yan upon the throne as the Yongle Emperor in 1402. The Yongle Emperor established Yan as a secondary capital and renamed it Beijing, constructed the Forbidden City, and restored the Grand Canal and the primacy of the imperial examinations in official appointments. He rewarded his eunuch supporters and employed them as a counterweight against the Confucian scholar-bureaucrats. One, Zheng He, led seven enormous voyages of exploration into the Indian Ocean as far as Arabia and the eastern coasts of Africa.

The rise of new emperors and new factions diminished such extravagances; the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor during the 1449 Tumu Crisis ended them completely. The imperial navy was allowed to fall into disrepair while forced labor constructed the Liaodong palisade and connected and fortified the Great Wall of China into its modern form. Wide-ranging censuses of the entire empire were conducted decennially, but the desire to avoid labor and taxes and the difficulty of storing and reviewing the enormous archives at Nanjing hampered accurate figures. Estimates for the late-Ming population vary from 160 to 200 million, but necessary revenues were squeezed out of smaller and smaller numbers of farmers as more disappeared from the official records or “donated” their lands to tax-exempt eunuchs or temples. Haijin laws intended to protect the coasts from “Japanese” pirates instead turned many into smugglers and pirates themselves.

By the 16th century, however, the expansion of European trade – albeit restricted to islands near Guangzhou like Macau – spread the Columbian Exchange of crops, plants, and animals into China, introducing chili peppers to Sichuan cuisine and highly productive corn and potatoes, which diminished famines and spurred population growth. The growth of Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch trade created new demand for Chinese products and produced a massive influx of Japanese and American silver. This abundance of specie remonetized the Ming economy, whose paper money had suffered repeated hyperinflation and was no longer trusted. While traditional Confucians opposed such a prominent role for commerce and the newly rich it created, the heterodoxy introduced by Wang Yangming permitted a more accommodating attitude. Zhang Juzheng’s initially successful reforms proved devastating when a slowdown in agriculture produced by the Little Ice Age joined changes in Japanese and Spanish policy that quickly cut off the supply of silver now necessary for farmers to be able to pay their taxes. Combined with crop failure, floods, and epidemic, the dynasty collapsed before the rebel leader Li Zicheng, who was defeated by the Manchu-led Eight Banner armies who founded the Qing dynasty.

|

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts increased across China in the 14th century, Zhu Yuanzhang rose to command the forces that conquered China, ending the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and forcing the Mongols to retreat to the Eurasian Steppe. Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and established the Ming dynasty at the beginning of 1368 and occupied the Yuan capital, Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing), with his army that same year. Trusting only his family, he made his many sons feudal princes along the northern marches and the Yangtze valley. Having outlived his eldest son Zhu Biao, Zhu enthroned Zhu Biao’s son via a series of instructions. This ended in failure when the Jianwen Emperor’s attempts to unseat his uncles led to the Jingnan Rebellion.

As famine, plagues and peasant revolts increased across China in the 14th century, Zhu Yuanzhang rose to command the forces that conquered China, ending the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and forcing the Mongols to retreat to the Eurasian Steppe. Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and established the Ming dynasty at the beginning of 1368 and occupied the Yuan capital, Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing), with his army that same year. Trusting only his family, he made his many sons feudal princes along the northern marches and the Yangtze valley. Having outlived his eldest son Zhu Biao, Zhu enthroned Zhu Biao’s son via a series of instructions. This ended in failure when the Jianwen Emperor’s attempts to unseat his uncles led to the Jingnan Rebellion..svg/280px-Ming_Empire_cca_1580_(en).svg.png)