|

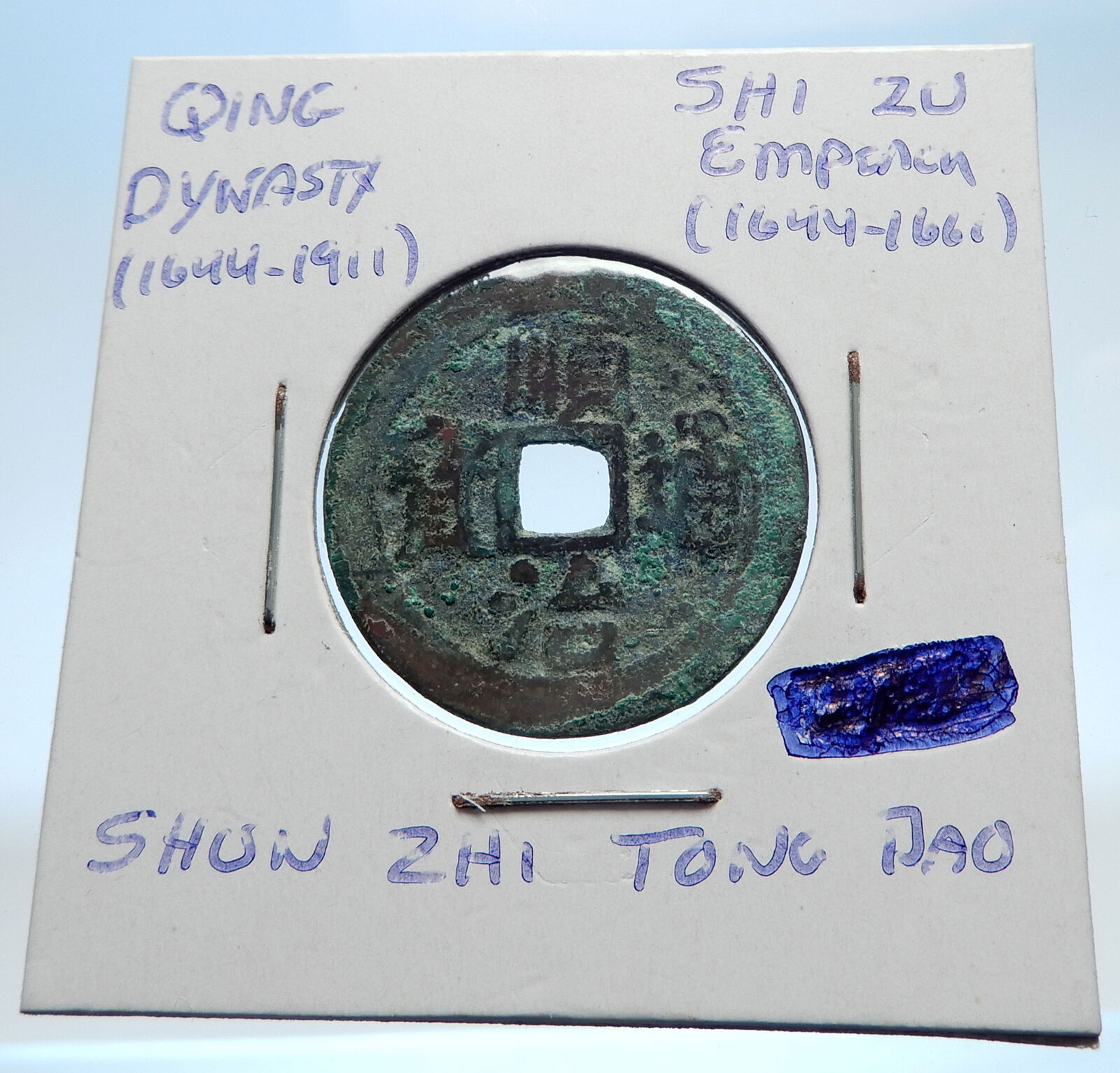

China – Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 A.D.)

Si Zong – Emperor: 1628-1644 A.D.

Bronze Cash 23mm

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The Chongzhen Emperor (Chinese: 崇禎; pinyin: Chóngzhēn; 6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian (Chinese: 朱由檢; pinyin: Zhū Yóujiǎn), was the 17th and last emperor of the Ming dynasty in China. “Chongzhen,” the era name of his reign, means “honorable and auspicious.” The Chongzhen Emperor (Chinese: 崇禎; pinyin: Chóngzhēn; 6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian (Chinese: 朱由檢; pinyin: Zhū Yóujiǎn), was the 17th and last emperor of the Ming dynasty in China. “Chongzhen,” the era name of his reign, means “honorable and auspicious.”

Zhu Youjian was son of the Taichang Emperor and younger brother of the Tianqi Emperor, whom he succeeded to the throne in 1627. He battled peasant rebellions and was not able to defend the northern frontier against the Manchu. When rebels reached the capital Beijing in 1644, he committed suicide, ending the Ming dynasty. The Manchu formed the succeeding Qing dynasty.

Legacy

While the Chongzhen Emperor was not especially incompetent by the standards of the later Ming, he nevertheless sealed the fate of the Ming dynasty. In ways, he did his best to save the dynasty. However, despite a reputation for hard work, the emperor’s paranoia, impatience, stubbornness and lack of regard for the plight of his people doomed his crumbling empire. His attempts at reform did not take into account the considerable decline of Ming power, which was already far advanced at the time of his accession. Over the course of his 17-year reign, the Chongzhen Emperor executed seven military governors, 11 regional commanders, replaced his minister of defence 14 times, and appointed an unprecedented 50 ministers to the Grand Secretariat (equivalent to the cabinet and chancellor). Even though the Ming dynasty still possessed capable commanders and skilled politicians in its dying years, the Chongzhen Emperor’s impatience and paranoid personality prevented any of them from enacting any real plan to salvage a perilous situation.

In particular, the Chongzhen Emperor’s execution of Yuan Chonghuan on extremely flimsy grounds was regarded as the decisively fatal blow. At the time of his death, Yuan was supreme commander of all Ming forces in the northeast, and had just rushed from the borders to defend the capital against a surprise Manchu invasion. For much of the preceding decade, Yuan had served as the Ming Empire’s bulwark in the north, where he was responsible for securing Ming borders at a time when the Empire was suffering humiliating defeat after defeat. His unjust death destroyed Ming military morale and removed one of the greatest obstacles to the eventual Manchu conquest of China.

The Ming dynasty was the ruling dynasty of China – then known as the Great Ming Empire – for 276 years (1368-1644) following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last imperial dynasty in China ruled by ethnic Han Chinese. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng (who established the Shun dynasty, soon replaced by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty), regimes loyal to the Ming throne – collectively called the Southern Ming – survived until 1683.

.svg/280px-Ming_Empire_cca_1580_(en).svg.png)

Ming China around 1580

The Hongwu Emperor (ruled 1368-98) attempted to create a society of self-sufficient rural communities ordered in a rigid, immobile system that would guarantee and support a permanent class of soldiers for his dynasty: the empire’s standing army exceeded one million troops and the navy’s dockyards in Nanjing were the largest in the world. He also took great care breaking the power of the court eunuchs[6] and unrelated magnates, enfeoffing his many sons throughout China and attempting to guide these princes through the Huang-Ming Zuxun, a set of published dynastic instructions. This failed spectacularly when his teenage successor, the Jianwen Emperor, attempted to curtail his uncles’ power, prompting the Jingnan Campaign, an uprising that placed the Prince of Yan upon the throne as the Yongle Emperor in 1402. The Yongle Emperor established Yan as a secondary capital and renamed it Beijing, constructed the Forbidden City, and restored the Grand Canal and the primacy of the imperial examinations in official appointments. He rewarded his eunuch supporters and employed them as a counterweight against the Confucian scholar-bureaucrats. One, Zheng He, led seven enormous voyages of exploration into the Indian Ocean as far as Arabia and the eastern coasts of Africa.

The rise of new emperors and new factions diminished such extravagances; the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor during the 1449 Tumu Crisis ended them completely. The imperial navy was allowed to fall into disrepair while forced labor constructed the Liaodong palisade and connected and fortified the Great Wall of China into its modern form. Wide-ranging censuses of the entire empire were conducted decennially, but the desire to avoid labor and taxes and the difficulty of storing and reviewing the enormous archives at Nanjing hampered accurate figures. Estimates for the late-Ming population vary from 160 to 200 million, but necessary revenues were squeezed out of smaller and smaller numbers of farmers as more disappeared from the official records or “donated” their lands to tax-exempt eunuchs or temples. Haijin laws intended to protect the coasts from “Japanese” pirates instead turned many into smugglers and pirates themselves.

By the 16th century, however, the expansion of European trade – albeit restricted to islands near Guangzhou like Macau – spread the Columbian Exchange of crops, plants, and animals into China, introducing chili peppers to Sichuan cuisine and highly productive corn and potatoes, which diminished famines and spurred population growth. The growth of Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch trade created new demand for Chinese products and produced a massive influx of Japanese and American silver. This abundance of specie remonetized the Ming economy, whose paper money had suffered repeated hyperinflation and was no longer trusted. While traditional Confucians opposed such a prominent role for commerce and the newly rich it created, the heterodoxy introduced by Wang Yangming permitted a more accommodating attitude. Zhang Juzheng’s initially successful reforms proved devastating when a slowdown in agriculture produced by the Little Ice Age joined changes in Japanese and Spanish policy that quickly cut off the supply of silver now necessary for farmers to be able to pay their taxes. Combined with crop failure, floods, and epidemic, the dynasty collapsed before the rebel leader Li Zicheng, who was defeated by the Manchu-led Eight Banner armies who founded the Qing dynasty.

|

The Chongzhen Emperor (Chinese: 崇禎; pinyin: Chóngzhēn; 6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian (Chinese: 朱由檢; pinyin: Zhū Yóujiǎn), was the 17th and last emperor of the Ming dynasty in China. “Chongzhen,” the era name of his reign, means “honorable and auspicious.”

The Chongzhen Emperor (Chinese: 崇禎; pinyin: Chóngzhēn; 6 February 1611 – 25 April 1644), personal name Zhu Youjian (Chinese: 朱由檢; pinyin: Zhū Yóujiǎn), was the 17th and last emperor of the Ming dynasty in China. “Chongzhen,” the era name of his reign, means “honorable and auspicious.” .svg/280px-Ming_Empire_cca_1580_(en).svg.png)