|

France

Louis IV, d’Outremer – King: 936-954 AD

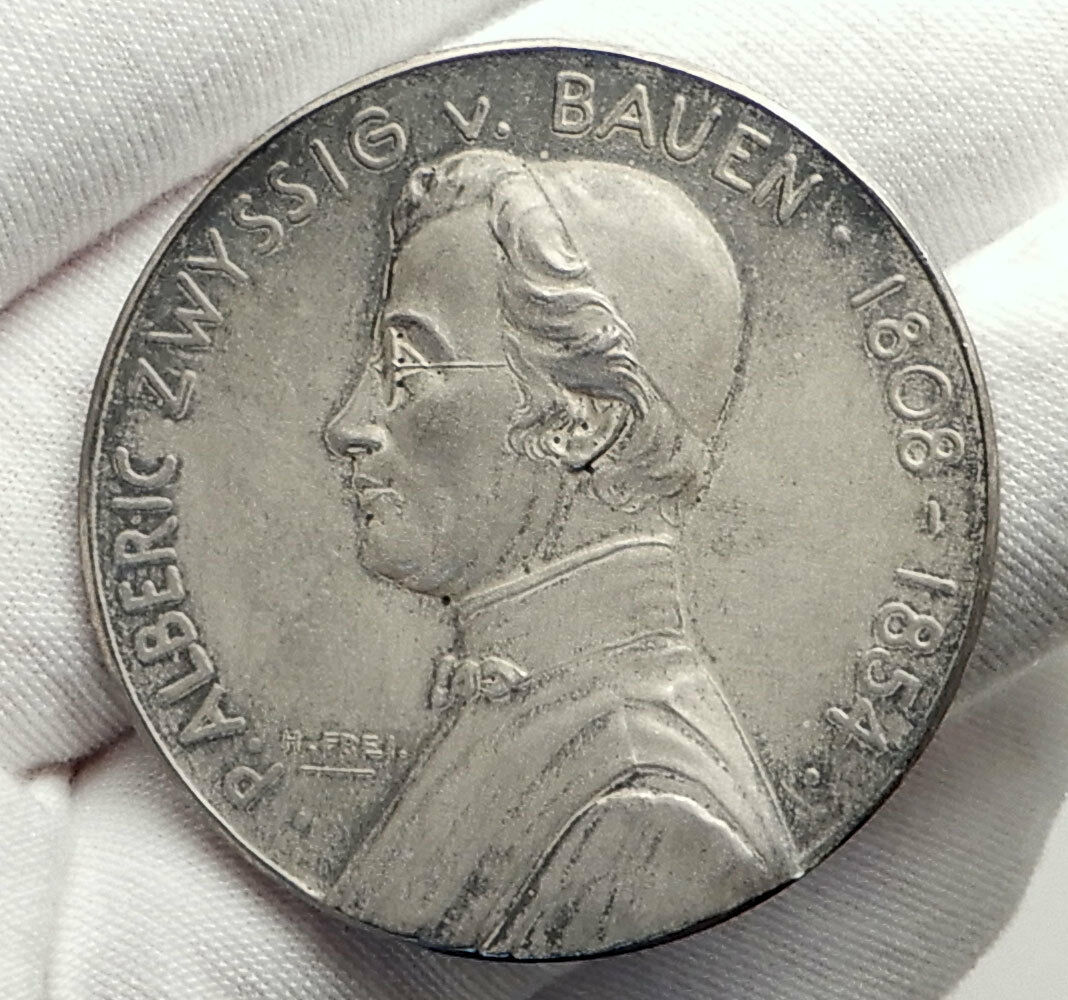

1839 Medal 51mm (66.00 grams)

1839

LOUIS IV DIT D’OUTREMER ROI DE FRANCE CAQUE-F,

King facing right.

LOUIS IV DIT D’OUTREMER. 33 EME ROI. FILS DE

OCARLES LE SIMPLE. NE 921. ROI 936. SEJOUR EN

ANGLETERRE 924 A 936. INVASIONS DES HONGROIS

937. LIGUE DES SEIGNEURS 938. PRISE DE RHIEMS

PAR LES REBELLES 940 GUERRE EN NORMANDI ET

CAPTIVITE DU ROI 942 A 945. RESTITUTION DE LA

NORMANDIE 945. FIN DE LA CAPTIVITE DU ROI

946. LIGUE AVEC OTTON ET ARNOULD 946. CONCILE

D’INGELHEIM 948. TRAITE AVEC HUGUES LE GRAND 950

GUERRE EN AUVERGNE 951. MORT 954., Inscription.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Louis IV (September 920 / September 921 – 10 September 954 called d’Outremer or Transmarinus (both meaning “from overseas”), reigned as king of West Francia from 936 to 954. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, he was the only son of king Charles the Simple and his second wife Eadgifu of Wessex, daughter of King Edward the Elder of Wessex. His reign is mostly known thanks to the Annals of Flodoard and the later Historiae of Richerus.

Having arrived on the continent, Louis IV was a young man of fifteen, who spoke neither Latin nor Old French, but probably spoke Old English. He knew nothing about his new kingdom. Hugh the Great, after negotiating with the most powerful nobles of the Kingdom – (William I Longsword of Normandy, Herbert II of Vermandois and Arnulf of Flanders) – was appointed guardian of the new king.

The young king quickly became a puppet of Hugh the Great, who had reigned de facto since the death of his father Robert in 923. Territorially, Louis IV was quite helpless since he possessed few lands around the ancient Carolingian domains (Compiègne, Quierzy, Verberie, Ver-lès-Chartres and Ponthion), and some abbeys (Saint-Jean in Laon, Saint-Corneille in Compiègne, Corbie and Fleury-sur-Loire) and collected the revenues from the province of Reims. We know that king had the power to appoint the suffragants of the Archbishopric of Reims. During this time Laon became the centre of the small Carolingian heartland, compared with the possessions in the Loire Valley of the Robertians.

Hugh the Great’s power came from the extraordinary title of dux Francorum (duke of the Franks) that Louis IV repeatedly confirmed in 936, 943 and 954; and his rule over the Marches of Neustria, where he reigned as princeps (territorial prince). This title was for the first time formalized by the Royal Chancery.

Thus the royal edicts of the second half of 936 confirm the pervasiveness of Hugh the Great: it is said that Duke of the Franks “in all but reigned over us”.

Hugh also denied the rights to the principality of Burgundy that Hugh the Black thought he had acquired after the death of his brother King Rudolph.

From the beginning of 937 Louis IV, called by some “The King of the Duke” (le roi du duc) tried to halt the virtual regency of the Duke of the Franks; in the contemporary charters, Hugh the Great appears only as “count” as if the ducal title was taken from him by the king. But Louis IV hesitated about this move, because the ducal title was already given to Hugh the Great by Charles the Simple in 914. But a serious misconduct probably took place at that time, because Louis IV removed the title from him. For his part, Hugh the Great continued to claim to be the duke of the Franks. In a letter from 938 the pope called him duke of the Franks, three years later (941) he presided a meeting in Paris during which he raised personally, in the manner of a king, his viscounts to the rank of counts. Finally, Hugh the Great had the decisive respect of the entire episcopate of France.

Louis IV and his supporters, 938–939

The rivalries between the nobility appeared as the only hope for the Louis IV to free himself from the regency of Hugh the Great. In 937 Louis IV began to rely more on his Chancellor Artald, Archbishop of Reims, Hugh the Black and William I Longsword, all enemies of Hugh the Great. He also received the homage of other important nobles like Alan II, Duke of Brittany (who also spent part of his life in England) and Sunyer, Count of Barcelona. Nevertheless, the support for the young king was still limited, until the Pope clearly favored him after he forced the French nobles to renew their homage to the king in 942. The King’s power in the south was symbolic since the death of the last Count of the Spanish March in 878.

Hugh the Great’s response to the King’s alliances approximating Herbert II of Vermandois, a very present ruler in minor France: it possessed a tower, called château Gaillot in the city of Laon. The following year, the King seized the tower but Herbert II conquered the fortresses of Reims. Flodoard related the events as follows:

-

- But Louis, called by the archbishop Artaud returned and besieged Laon where a new citadel was built by Herbert. He undermines and overthrows many machines walls and finally took it with great difficulty.

War over Lotharingia

Louis IV then looked to the Lotharingia, the land of his ancestors and began attempts to conquer it. In 939 Gilbert, Duke of Lotharingia rebelled against King Otto I of East Francia and offered the crown to Louis IV, who received homage of the Lotharingian aristocracy in Verdun on his way to Aachen. On 2 October 939, Gilbert drowned in Rhine while escaping from the forces of Otto I after the defeat at the Battle of Andernach. Louis IV used this opportunity to strengthen his domain over Lotharingia by marrying Giselbert’s widow, Gerberga of Saxony (end 939), without the consent of her brother King Otto I. The wedding did not stop Otto I who, after alliance with Hugh the Great, Herbert II of Vermandois and William I Longsword, resumed his invasion of Lotharingia and advanced towards Reims.

Crisis of the royal power, 940–941

In 940 the East Frankish invaders finally conquered the city of Reims, where archbishop Artald was expelled and replaced by Hugh of Vermandois, younger son of Herbert II, who also seized the patrimony of Saint-Remi. About this, Flodoard wrote:

-

- These are the same Franks who want this King, who crossed the sea at their request, the same ones who sworn loyalty to him and lied to God and that King?

Flodoard also publishes at the end of his Annals the testimony of a girl from Reims (the Visions of Flothilde) who predicted the expulsion of Artald from Reims. Flothilde mentioned that the saints are alarmed about the disloyalty of the nobles against the King. This testimony was widely believed, especially among the population of Reims, who believed that the internal order and peace come from the oaths of loyalty to the King, while Artald was blamed of having forsaken divine service. Contemporary Christian tradition affirmed that Saint Martin attended the coronation of 936. Now the two royal patron saints, Saint Remi and Saint Denis, seem to have turned back to the King’s rule. To soften the anger of the saints, in the middle of the siege of Reims by Hugh the Great and William I Longsword, Louis IV went to Saint Remi Basilica and promised to the saint to pay him a pound of silver every year.

In the meanwhile, Hugh the Great and his vassals had sworn allegiance to Otto I, who moved to the Carolingian Palace of Attigny before his unsuccessful siege of Laon. In 941 the royal army, which tried to oppose Otto’s invasion, was defeated and Artald was forced to submit to the rebels. Now Louis IV was surrendered in the only property that remained in his hands: the city of Laon. Otto I believed that the power Louis IV was sufficiently diminished and proposed a reconciliation with the Duke of the Franks and the Count of Vermandois. From that point on, Otto I was the new arbitrator in the West Francia.

Intervention in Normandy, 943–946

On 17 December 942 William I Longsword was ambushed and killed by men of Arnulf I, Count of Flanders at Picquigny and on 23 February 943 Herbert II, Count of Vermandois died of natural causes. The heir of Duchy of Normandy was Richard I, the ten-year-old son of William born from his Breton concubine, while Herbert II left as heirs four adult sons.

Louis IV took advantage of the internal disorder in the Duchy of Normandy and entered Rouen, where he received the homage from part of the Norman aristocracy and offered his protection to the young Richard I with the help of Hugh the Great. The regency of Normandy was entrusted to the faithful Herluin, Count of Montreuil (who was also a vassal of Hugh the Great), while Richard I was imprisoned first in Laon and then in Château de Coucy. In Vermandois, the King also took measures to diminish the power of Herbert II’s sons by dividing their lands between them: Eudes (as Count of Amiens), Herbert III (as Count of Château-Thierry), Robert (as Count of Meaux) and Albert (as Count of Saint-Quentin). Albert of Vermandois took the side of the King and paid homage to him, while the Abbey of Saint-Crépin in Soissons was finally given to Renaud of Roucy. In 943, during the homage given to the King, Hugh the Great recovered the ducatus Franciae (Duchy of France) title and the rule over Burgundy.

During the summer of 945 Louis IV went to Normandy after being called by his faithful Herluin, who was a victim of a serious revolt. While the two were riding, they were ambushed near Bayeux. Herluin was killed, but Louis IV managed to escape to Rouen; where he was finally captured by the Normans. The kidnappers demanded from Queen Gerberga that she send her two sons Lothair and Charles as hostages in exchange for the release of her husband. The Queen only sent her youngest son Charles, with Bishop Guy of Soissons taking the place of Lothair, the eldest son and heir. Like his father, Louis IV was kept in captivity, then sent to Hugh the Great. On his orders, the king was placed under the custody of Theobald I, Count of Blois for several months. The ambush and capture of the King were probably ordered by Hugh the Great, who wanted to permanently end his attempts of political independence. Ultimately, probably by the pressure of the Frankish nobles and Kings Otto I and Edmund I of England, Hugh the Great decided to release Louis IV.

Hugh was the only one who would decide if Louis IV could be restored or deposed. In return for the release of the King, he demanded the surrender of Laon, which was entrusted to his vassal Thibaud. The Carolingian kinship was in the abyss, because it no longer held or controlled anything.

In June 946, a royal charter called optimistically the “eleventh year of the reign of Louis when he had recovered the Francia“. This charter is the first official text who identified only the Western Frankish kingdom (sometimes called West Francia by some historians). This statement is consistent with the fact that the title of King of the Franks, used since 911 by Charles the Simple was thereafter continuously claimed by the Kings of the Western Kingdom after the Treaty of Verdun, including the non-Carolingians ones. Among the Kings of the East, sometimes called Germanic Kings, this claim was occasional and disappeared completely after the 11th century.

Trial of Hugh the Great, 948–949

Otto I was not satisfied with the growing power of Hugh the Great who, although not accepted by the whole kingdom, respected the division of powers. In 946 Otto I and Conrad I of Burgundy raised an army and tried to take Laon and then Senlis. They invaded Reims with a large army, according to Flodoard. Archbishop Hugh of Vermandois escaped and Artald was restored. “Robert, Archbishop of Trier and Frederick, Archbishop of Mainz take everyone by the hand” (Flodoard). A few months later, Louis IV joined the fight against Hugh the Great and his allies at the Battle of Rouen. In the spring of 947, Louis and his wife Gerberga spent the Easter holidays in Aachen at the court of Otto I, asking him for help in their war against Hugh the Great.

Between late 947 and late 948, four imperial synods were held by Otto I between Meuse and Rhine to settle the fate of the Archbishopric of Reims and Hugh the Great. In Synod of Ingelheim (June 948) participated the apostolic legate, thirty German and Burgundian bishops and finally Artald and his suffragants of Laon among the Frankish clerics. Louis IV presented his claims against Hugh the Great at the synod. The surviving final acts determined: “Anybody had the right to undermine the royal power or treacherously revolted against their King. We therefore decide that Hugh was the invasor and abductor of Louis, and he will be struck with the sword of the excommunication unless he presents himself and give a satisfaction to us for his perversity”.

But the Duke of the Franks, not paying attention to the sentence, devastated Soissons, Reims and profaned dozens of churches. In the meanwhile, his vassal and relative Theobald I, Count of Blois (nicknamed “the Trickster”) who had married Luitgarde of Vermandois, daughter of Herbert II of Vermandois and widow of William I Longsword, had built a fortress in Montaigu in Laon to humiliate the king, and seized the lordship of Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique in Reims. The Synod of Trier (September 948) decided to excommunicate him for his actions. Guy I, Count of Soissons, who ordained Hugh of Vermandois, must repent, while Thibaud of Amiens and Yves of Senlis, who both consecrated Hugh, were excommunicated. The King, with the help of Arnold, deposed Thibaud from the seat of Amiens and placed the faithful Raimbaud in his place (949).

Return of the balance

The last step in the emancipation of Louis IV shows that his reign wasn’t entirely negative. In 949 he entered Laon, where by command of Hugh the Great, Theobald I of Blois surrendered to him the fortress he had built a few months earlier. The King recovered, at the expense of Herbert II’s vassals, the château of Corbeny which his father had given to Saint-Remi of Reims and also authorized archbishop Artald to mint coins in his city.

In 950 Louis IV and Hugh the Great finally reconciled. After the death of Hugh the Black in 952, Hugh the Great captured his half of Burgundy. Louis IV, now allied with Arnulf I of Flanders and Adalbert I, Count of Vermandois, exercised real authority only north of the river Loire. He also rewarded Liétald II of Mâcon and Charles Constantine of Vienne for their loyalty. For a long time Louis IV and his son Lothair were the last kings to venture south of the river Loire.

In 951 Louis IV fell seriously ill during a stay in Auvergne and decided to associate to the throne his eldest son and heir, the ten-year-old Lothair. During his stay, he received homage of Bishop Étienne II, brother of the viscount of Clermont. Louis IV recovered from his disease thanks to the care of his wife Gerberga, who during the reign of her husband had a key role. The royal couple had seven children, of whom only three survived infancy: Lothair, the eldest son and future King – that Flodoard cites not to be confused with the son of Louis the Pious: Lotharius puer, filius Ludowici (infant Lothair, son of Louis)–, Mathilde – who in 964 married King Conrad I of Burgundy – and Charles – who was invested as Duke of Lower Lorraine by his cousin Emperor Otto II in 977–.

During the 950s, the royal power network was entrenched by construction of several palaces in the towns that were recovered by the King. Under Louis IV (and also during the reign of his son), there is a geographical tightening of royal lands around Compiègne, Laon and Reims which eventually gave Laon an incontestable primacy. Thus, through the charters issued by the Royal Chancery, can be followed the stays of Louis IV. The King spent mostly of his time in the palaces of Reims (21% of the charters), Laon (15%), Compiègne and Soissons (2% for each of them).

Flodoard records in 951 that Queen Eadgifu (Ottogeba regina mater Ludowici regis), who since her return with her son to France retired to the Abbey of Notre Dame in Laon (abbatiam sanctæ Mariæ…Lauduni), where she became the Abbess, was abducted from there by Herbert III of Vermandois, Count of Château-Thierry (Heriberti…Adalberti fratris), who married her shortly after; the King, furious about this (rex Ludowicus iratus) confiscated the Abbey of Notre Dame from his mother and donated it to his wife Gerberga (Gerbergæ uxori suæ).

In the early 950s, Queen Gerberga developed an increased eschatological fear, and began to consult Adso of Montier-en-Der; being highly educated, she commissioned to him the De ortu et tempore antichristi (The birth and era of the Antichrist). Adso reassured the Queen that the arrival of the Antichrist would not take place before the end of the Kingdoms of France and Germany, the two Imperia fundamentals of the universe. In consequence, the Frankish King could continue his reign without fear, because Heaven was the door of legitimacy.

At the end of the summer of 954, Louis IV went riding with his companions on the road from Laon to Reims. As he crossed the forest of Voas (near to his palace in Corbeny), he saw a wolf and attempted to capture it. Flodoard, from whom these details are known, said that the King fell from his horse. Urgently carried to Reims, he eventually died from his injuries on 10 September. For the Reims canons, the wolf whom the king tried to hunt wasn’t an animal but a fantastic creature, a divine supernatural intervention.

Flodoard recalled indeed that in 938 Louis IV had captured Corbeny in extreme brutality and without respecting the donations to the monks made by his father. Thus God could punish the King and his descendants with the curse of the wolf as a “plague”. The later events are disturbing. According to Flodoard Louis reportedly died from tuberculosis (then called pesta elephantis); in 986 his son Lothair died by a “plague” after he besieged Verdun, and finally his grandson Louis V died in 987 from injuries received when falling from his horse while hunting, a few months after he besieged Reims for the trial of archbishop Adalberon.

France, officially the French Republic (French: République française), is a sovereign state comprising territory in western Europe and several overseas regions and territories. The European part of France, called Metropolitan France, extends from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea, and from the Rhine to the Atlantic Ocean. France spans 640,679 square kilometres (247,368 sq mi) and has a total population of 67 million. It is a unitary semi-presidential republic with the capital in Paris, the country’s largest city and main cultural and commercial centre. The Constitution of France establishes the state as secular and democratic, with its sovereignty derived from the people. France, officially the French Republic (French: République française), is a sovereign state comprising territory in western Europe and several overseas regions and territories. The European part of France, called Metropolitan France, extends from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea, and from the Rhine to the Atlantic Ocean. France spans 640,679 square kilometres (247,368 sq mi) and has a total population of 67 million. It is a unitary semi-presidential republic with the capital in Paris, the country’s largest city and main cultural and commercial centre. The Constitution of France establishes the state as secular and democratic, with its sovereignty derived from the people.

During the Iron Age, what is now Metropolitan France was inhabited by the Gauls, a Celtic people. The Gauls were conquered in 51 BC by the Roman Empire, which held Gaul until 486. The Gallo-Romans faced raids and migration from the Germanic Franks, who dominated the region for hundreds of years, eventually creating the medieval Kingdom of France. France emerged as a major European power in the Late Middle Ages, with its victory in the Hundred Years’ War (1337 to 1453) strengthening French state-building and paving the way for a future centralized absolute monarchy. During the Renaissance, France experienced a vast cultural development and established the beginning of a global colonial empire. The 16th century was dominated by religious civil wars between Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots).

France became Europe’s dominant cultural, political, and military power under Louis XIV. French philosophers played a key role in the Age of Enlightenment during the 18th century. In 1778, France became the first and the main ally of the new United States in the American Revolutionary War. In the late 18th century, the absolute monarchy was overthrown in the French Revolution. Among its legacies was the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, one of the earliest documents on human rights, which expresses the nation’s ideals to this day. France became one of modern history’s earliest republics until Napoleon took power and launched the First French Empire in 1804. Fighting against a complex set of coalitions during the Napoleonic Wars, he dominated European affairs for over a decade and had a long-lasting impact on Western culture. Following the collapse of the Empire, France endured a tumultuous succession of governments: the monarchy was restored, it was replaced in 1830 by a constitutional monarchy, then briefly by a Second Republic, and then by a Second Empire, until a more lasting French Third Republic was established in 1870. By the 1905 law, France adopted a strict form of secularism, called laïcité, which has become an important federative principle in the modern French society. France became Europe’s dominant cultural, political, and military power under Louis XIV. French philosophers played a key role in the Age of Enlightenment during the 18th century. In 1778, France became the first and the main ally of the new United States in the American Revolutionary War. In the late 18th century, the absolute monarchy was overthrown in the French Revolution. Among its legacies was the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, one of the earliest documents on human rights, which expresses the nation’s ideals to this day. France became one of modern history’s earliest republics until Napoleon took power and launched the First French Empire in 1804. Fighting against a complex set of coalitions during the Napoleonic Wars, he dominated European affairs for over a decade and had a long-lasting impact on Western culture. Following the collapse of the Empire, France endured a tumultuous succession of governments: the monarchy was restored, it was replaced in 1830 by a constitutional monarchy, then briefly by a Second Republic, and then by a Second Empire, until a more lasting French Third Republic was established in 1870. By the 1905 law, France adopted a strict form of secularism, called laïcité, which has become an important federative principle in the modern French society.

France reached its territorial height during the 19th and early 20th centuries, when it ultimately possessed the second-largest colonial empire in the world. In World War I, France was one of the main winners as part of the Triple Entente alliance fighting against the Central Powers. France was also one of the Allied Powers in World War II, but came under occupation by the Axis Powers in 1940. Following liberation in 1944, a Fourth Republic was established and later dissolved in the course of the Algerian War. The Fifth Republic, led by Charles de Gaulle, was formed in 1958 and remains to this day. Following World War II, most of the empire became decolonized.

Throughout its long history, France has been a leading global center of culture, making significant contributions to art, science, and philosophy. It hosts Europe’s third-largest number of cultural UNESCO World Heritage Sites (after Italy and Spain) and receives around 83 million foreign tourists annually, the most of any country in the world. France remains a great power with significant cultural, economic, military, and political influence. It is a developed country with the world’s sixth-largest economy by nominal GDP and eight-largest by purchasing power parity. According to Credit Suisse, France is the fourth wealthiest nation in the world in terms of aggregate household wealth. It also possesses the world’s second-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ), covering 11,035,000 square kilometres (4,261,000 sq mi).

French citizens enjoy a high standard of living, and the country performs well in international rankings of education, health care, life expectancy, civil liberties, and human development. France is a founding member of the United Nations, where it serves as one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. It is a member of the Group of 7, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and La Francophonie. France is a founding and leading member state of the European Union (EU).

|

France, officially the French Republic (French: République française), is a sovereign state comprising territory in western Europe and several overseas regions and territories. The European part of France, called Metropolitan France, extends from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea, and from the Rhine to the Atlantic Ocean. France spans 640,679 square kilometres (247,368 sq mi) and has a total population of 67 million. It is a unitary semi-presidential republic with the capital in Paris, the country’s largest city and main cultural and commercial centre. The Constitution of France establishes the state as secular and democratic, with its sovereignty derived from the people.

France, officially the French Republic (French: République française), is a sovereign state comprising territory in western Europe and several overseas regions and territories. The European part of France, called Metropolitan France, extends from the Mediterranean Sea to the English Channel and the North Sea, and from the Rhine to the Atlantic Ocean. France spans 640,679 square kilometres (247,368 sq mi) and has a total population of 67 million. It is a unitary semi-presidential republic with the capital in Paris, the country’s largest city and main cultural and commercial centre. The Constitution of France establishes the state as secular and democratic, with its sovereignty derived from the people.

France became Europe’s dominant cultural, political, and military power under Louis XIV. French philosophers played a key role in the Age of Enlightenment during the 18th century. In 1778, France became the first and the main ally of the new United States in the American Revolutionary War. In the late 18th century, the absolute monarchy was overthrown in the French Revolution. Among its legacies was the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, one of the earliest documents on human rights, which expresses the nation’s ideals to this day. France became one of modern history’s earliest republics until Napoleon took power and launched the First French Empire in 1804. Fighting against a complex set of coalitions during the Napoleonic Wars, he dominated European affairs for over a decade and had a long-lasting impact on Western culture. Following the collapse of the Empire, France endured a tumultuous succession of governments: the monarchy was restored, it was replaced in 1830 by a constitutional monarchy, then briefly by a Second Republic, and then by a Second Empire, until a more lasting French Third Republic was established in 1870. By the 1905 law, France adopted a strict form of secularism, called laïcité, which has become an important federative principle in the modern French society.

France became Europe’s dominant cultural, political, and military power under Louis XIV. French philosophers played a key role in the Age of Enlightenment during the 18th century. In 1778, France became the first and the main ally of the new United States in the American Revolutionary War. In the late 18th century, the absolute monarchy was overthrown in the French Revolution. Among its legacies was the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, one of the earliest documents on human rights, which expresses the nation’s ideals to this day. France became one of modern history’s earliest republics until Napoleon took power and launched the First French Empire in 1804. Fighting against a complex set of coalitions during the Napoleonic Wars, he dominated European affairs for over a decade and had a long-lasting impact on Western culture. Following the collapse of the Empire, France endured a tumultuous succession of governments: the monarchy was restored, it was replaced in 1830 by a constitutional monarchy, then briefly by a Second Republic, and then by a Second Empire, until a more lasting French Third Republic was established in 1870. By the 1905 law, France adopted a strict form of secularism, called laïcité, which has become an important federative principle in the modern French society.