|

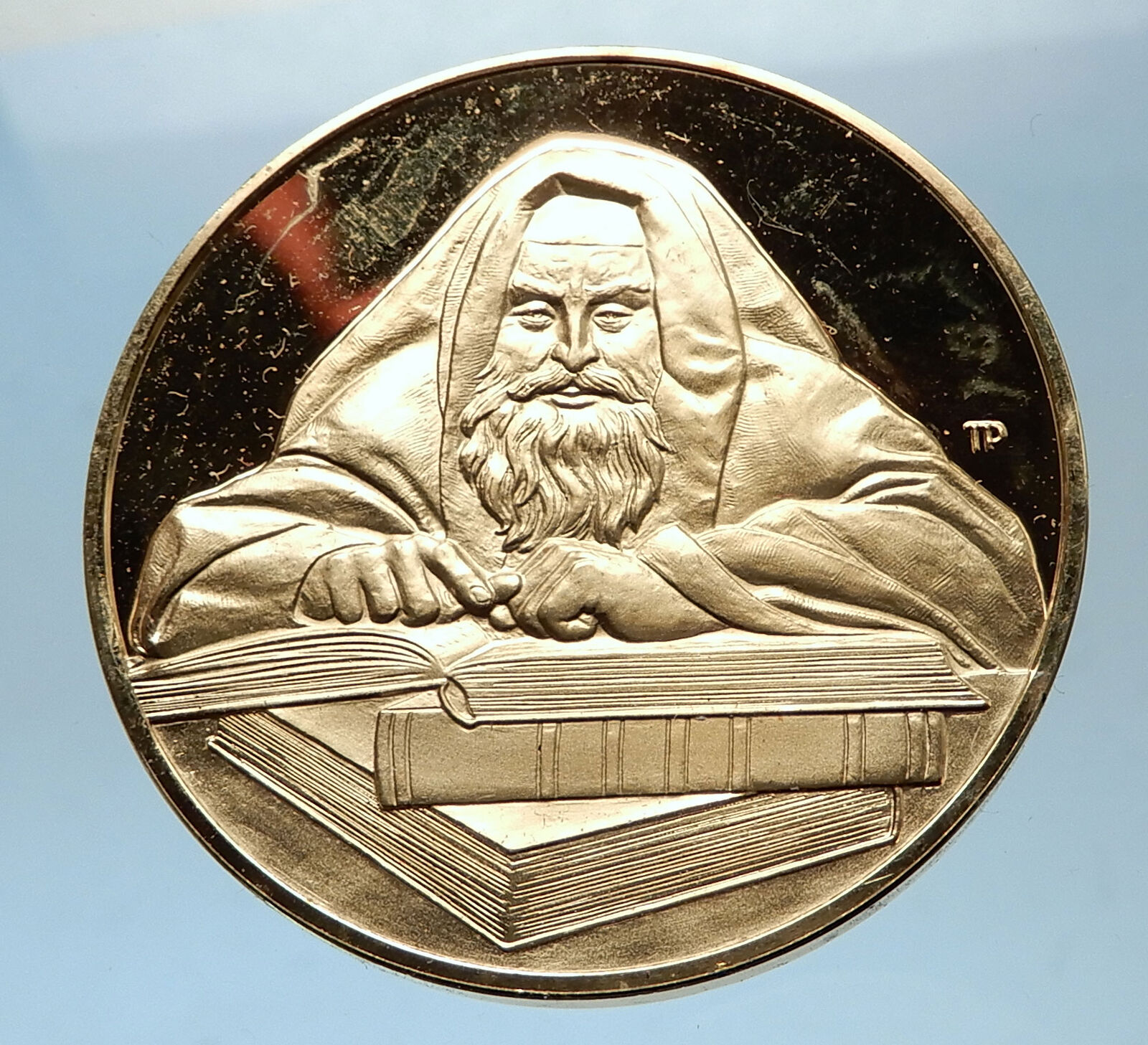

Austria – Franz Joseph I – Emperor: 2 December 1848 – 21 November 1916

Vienna World Exposition

1873 Bronze Medal 70mm (157.91 grams)

FRANZ JOSEPH I., KAISER VON OESTERREICH, KOENIG VON BOEHMEN ETC., APOT.

KOENIG VON UNGARAN * J. TAUTENHAYN, Franz facing right.

DEM FORTSCHRITTE WELTAUSSTELLUNG 1873 * WEIN *, Seated

female left, moving right: angel with wreath, two women, holding hands with

scepter and torch, gear and globe behind.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair (German: Weltausstellung 1873 Wien) was the large world exposition that was held in 1873 in the Austria-Hungarian capital Vienna. Its motto was “Culture and Education” (Kultur und Erziehung). The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair (German: Weltausstellung 1873 Wien) was the large world exposition that was held in 1873 in the Austria-Hungarian capital Vienna. Its motto was “Culture and Education” (Kultur und Erziehung).

As well as being a chance to showcase Austro-Hungarian industry and culture, the World’s Fair in Vienna commemorated Franz Joseph I’s 25th year as emperor.The main grounds were in the Prater, a park near the Danube River, and preparations cost £23.4 million.It lasted from May 1st to November 2nd, hosting about 7,225,000 visitors.

There were almost 26,000 exhibitorshoused in different buildings that were erected for this exposition, including the Rotunda (Rotunde), a large circular building in the great park of Prater designed by the Scottish engineer John Scott Russell. (The fair Rotunda was destroyed by fire on 17 September 1937.)

Russian pavilion

The Russian pavilion had a naval section designed by Viktor Hartmann. Exhibits included models of the Port of Rijekaand the Illés Relief model of Jerusalem.

Japanese pavilion

The Japanese exhibition at the fair was the product of years of preparation. The empire had received its invitation in 1871, close on the heels of the Meiji Restoration, and a government bureau was established to produce an appropriate response. Shigenobu Okuma, Tsunetami Sano, and its other officials were keen to use the event to raise the international standing of Japanese manufactures and boost exports. 24 engineers were also sent with its delegation to study cutting-edge Western engineering at the fair for use in Japanese industry.Art and cultural relics at the exhibit were verified by the Jinshin Survey, a months-long inspection tour of various imperial, noble, and temple holdings around the country.The most important products of each province were listed and two specimens of each were collected, one for display in Vienna and the other for preservation and display within Japan.Large-scale preparatory exhibitions with this second set of objects were conducted within Japan at the Tokyo Kaisei School (today the University of Tokyo) in 1871 and at the capital’s Confucian Temple in 1872; they eventually formed the core collection of the institution that became the Tokyo National Museum.

41 Japanese officials and government interpreters, as well as 6 Europeans in Japanese employ, came to Vienna to oversee the pavilion and the fair’s cultural events. 25 craftsmen and gardeners created the main pavilion, as well as a full Japanese garden with shrine and a model of the former pagoda at Tokyo’s imperial temple.Apart from the collection of regional objects, which focused on ceramics, cloisonné wares, lacquerware, and textiles, the displays also included the female golden shachi from Nagoya Castle and a papier-maché copy of the Kamakura Buddha.The year after the fair, Sano compiled a report on it which ran to 96 volumes divided into 16 parts, including a strong plea for the creation of a museum on western lines in the Japanese capital; the government further began hosting national industrial exhibitions at Ueno Park in 1877. 41 Japanese officials and government interpreters, as well as 6 Europeans in Japanese employ, came to Vienna to oversee the pavilion and the fair’s cultural events. 25 craftsmen and gardeners created the main pavilion, as well as a full Japanese garden with shrine and a model of the former pagoda at Tokyo’s imperial temple.Apart from the collection of regional objects, which focused on ceramics, cloisonné wares, lacquerware, and textiles, the displays also included the female golden shachi from Nagoya Castle and a papier-maché copy of the Kamakura Buddha.The year after the fair, Sano compiled a report on it which ran to 96 volumes divided into 16 parts, including a strong plea for the creation of a museum on western lines in the Japanese capital; the government further began hosting national industrial exhibitions at Ueno Park in 1877.

Ottoman pavilion

Osman Hamdi Bey, an archaeologist and painter, was chosen by the Ottoman government as commissary of the empire’s exhibits in Vienna. He organized the Ottoman pavilion with Victor Marie de Launay, a French-born Ottoman official and archivist, who had written the catalogue for the Ottoman Empire’s exhibition at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair.The Ottoman pavilion, located near the Egyptian pavilion (which had its own pavilion despite being a territory of the Ottoman Empire),in the park outside the Rotunde, included small replicas of notable Ottoman buildings and models of vernacular architecture: a replica of the Sultan Ahmed Fountain in the Topkapı Palace, a model Istanbul residence, a representative Turkish bath, a cafe, and a bazaar.The 1873 Ottoman pavilion was more prominent than its pavilion in 1867. The Vienna exhibition set off Western nations’ Osman Hamdi Bey, an archaeologist and painter, was chosen by the Ottoman government as commissary of the empire’s exhibits in Vienna. He organized the Ottoman pavilion with Victor Marie de Launay, a French-born Ottoman official and archivist, who had written the catalogue for the Ottoman Empire’s exhibition at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair.The Ottoman pavilion, located near the Egyptian pavilion (which had its own pavilion despite being a territory of the Ottoman Empire),in the park outside the Rotunde, included small replicas of notable Ottoman buildings and models of vernacular architecture: a replica of the Sultan Ahmed Fountain in the Topkapı Palace, a model Istanbul residence, a representative Turkish bath, a cafe, and a bazaar.The 1873 Ottoman pavilion was more prominent than its pavilion in 1867. The Vienna exhibition set off Western nations’  pavilions against Eastern pavilions, with the host, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, setting itself at the juncture between East and West.A report by the Ottoman commission for the exhibition expressed a goal of inspiring with their display “a serious interest Ottoman Empire on the part of the industrialists, traders, artists, and scholars of other nations….” pavilions against Eastern pavilions, with the host, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, setting itself at the juncture between East and West.A report by the Ottoman commission for the exhibition expressed a goal of inspiring with their display “a serious interest Ottoman Empire on the part of the industrialists, traders, artists, and scholars of other nations….”

The Ottoman pavilion included a gallery of mannequins wearing the traditional costumes of many of the varied ethnic groups of the Ottoman Empire. To supplement the cases of costumes, Osman Hamdi and de Launay created a photographic book of Ottoman costumes, the Elbise-i ‘Osmaniyye (Les costumes populaires de la Turquie), with photographs by Pascal Sébah. The photographic plates of the Elbise depicted traditional Ottoman costumes, commissioned from artisans working in the administrative divisions (vilayets) of the Empire, worn by men, women, and children who resembled the various ethnic and religious types of the empire, though the models were all found in Istanbul. The photographs are accompanied by texts describing the costumes in detail and commenting on the rituals and habits of the regions and ethnic groups in question.

Italian pavilion

Professor Lodovico Brunetti of Padua, Italy first displayed cremated ashes at the exhibition. He showed a model of the crematory, one of the first modern ones. He exhibited it with a sign reading, “Vermibus erepti, puro consummimur igni,” in english, “Saved from the worms, we are consumed by the flames.”

The online JS compressor tool will help you to optimize your scripts for a faster page loading.

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (Franz Joseph Karl; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and monarch of other states in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, from 2 December 1848 to his death. From 1 May 1850 to 24 August 1866 he was also President of the German Confederation. He was the longest-reigning Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, as well as the third-longest-reigning monarch of any country in European history, after Louis XIV of France and Johann II of Liechtenstein. Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (Franz Joseph Karl; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and monarch of other states in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, from 2 December 1848 to his death. From 1 May 1850 to 24 August 1866 he was also President of the German Confederation. He was the longest-reigning Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, as well as the third-longest-reigning monarch of any country in European history, after Louis XIV of France and Johann II of Liechtenstein.

In December 1848, Emperor Ferdinand abdicated the throne at Olomouc, as part of Minister-president Felix zu Schwarzenberg’s plan to end the Revolutions of 1848 in Hungary. This allowed Ferdinand’s nephew Franz Joseph to accede to the throne. Largely considered to be a reactionary, Franz Joseph spent his early reign resisting constitutionalism in his domains. The Austrian Empire was forced to cede its influence over Tuscany and most of its claim to Lombardy-Venetia to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, following the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859 and the Third Italian War of Independence in 1866. Although Franz Joseph ceded no territory to the Kingdom of Prussia after the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, the Peace of Prague (23 August 1866) settled the German question in favour of Prussia, which prevented the Unification of Germany from occurring under the House of Habsburg.

Franz Joseph was troubled by nationalism during his entire reign. He concluded the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which granted greater autonomy to Hungary and transformed the Austrian Empire into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, under his dual monarchy. His domains were then ruled peacefully for the next 45 years, but Franz Joseph personally suffered the tragedies of the execution of his brother Emperor Maximilian of Mexico in 1867, the suicide of his only son and heir, Crown Prince Rudolf, in 1889, and the assassination of his wife, Empress Elisabeth, in 1898.

After the Austro-Prussian War, Austria-Hungary turned its attention to the Balkans, which was a hotspot of international tension because of conflicting interests with the Russian Empire. The Bosnian Crisis was a result of Franz Joseph’s annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, which had been occupied by his troops since the Congress of Berlin (1878).

On 28 June 1914, the assassination of his nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo resulted in Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against the Kingdom of Serbia, which was Russia’s ally. That activated a system of alliances which resulted in World War I.

Franz Joseph died on 21 November 1916, after ruling his domains for almost 68 years. He was succeeded by his grandnephew Charles.

Austria, officially the Republic of Austria (German: Republik Österreich), is a federal republic and a landlocked country of over 8.5 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Hungary and Slovakia to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the west. The territory of Austria covers 83,879 square kilometres (32,386 sq mi). Austria’s terrain is highly mountainous, lying within the Alps; only 32% of the country is below 500 metres (1,640 ft), and its highest point is 3,798 metres (12,461 ft). The majority of the population speak local Bavarian dialects of German as their native language, and Austrian German in its standard form is the country’s official language. Other local official languages are Hungarian, Burgenland Croatian, and Slovene. Austria, officially the Republic of Austria (German: Republik Österreich), is a federal republic and a landlocked country of over 8.5 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Hungary and Slovakia to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the west. The territory of Austria covers 83,879 square kilometres (32,386 sq mi). Austria’s terrain is highly mountainous, lying within the Alps; only 32% of the country is below 500 metres (1,640 ft), and its highest point is 3,798 metres (12,461 ft). The majority of the population speak local Bavarian dialects of German as their native language, and Austrian German in its standard form is the country’s official language. Other local official languages are Hungarian, Burgenland Croatian, and Slovene.

The origins of modern-day Austria date back to the time of the Habsburg dynasty when the vast majority of the country was a part of the Holy Roman Empire. From the time of the Reformation, many Northern German princes, resenting the authority of the Emperor, used Protestantism as a flag of rebellion. The Thirty Years War, the influence of the Kingdom of Sweden and Kingdom of France, the rise of the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Napoleonic invasions all weakened the power of the Emperor in the North of Germany, but in the South, and in non-German areas of the Empire, the Emperor and Catholicism maintained control. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Austria was able to retain its position as one of the great powers of Europe and, in response to the coronation of Napoleon as the Emperor of the French, the Austrian Empire was officially proclaimed in 1804. Following Napoleon’s defeat, Prussia emerged as Austria’s chief competitor for rule of a larger Germany. Austria’s defeat by Prussia at the Battle of Königgrätz, during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 cleared the way for Prussia to assert control over the rest of Germany. In 1867, the empire was reformed into Austria-Hungary. After the defeat of France in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Austria was left out of the formation of a new German Empire, although in the following decades its politics, and its foreign policy, increasingly converged with those of the Prussian-led Empire. During the 1914 July Crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Germany guided Austria in issuing the ultimatum to Serbia that led to the declaration of World War I. The origins of modern-day Austria date back to the time of the Habsburg dynasty when the vast majority of the country was a part of the Holy Roman Empire. From the time of the Reformation, many Northern German princes, resenting the authority of the Emperor, used Protestantism as a flag of rebellion. The Thirty Years War, the influence of the Kingdom of Sweden and Kingdom of France, the rise of the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Napoleonic invasions all weakened the power of the Emperor in the North of Germany, but in the South, and in non-German areas of the Empire, the Emperor and Catholicism maintained control. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Austria was able to retain its position as one of the great powers of Europe and, in response to the coronation of Napoleon as the Emperor of the French, the Austrian Empire was officially proclaimed in 1804. Following Napoleon’s defeat, Prussia emerged as Austria’s chief competitor for rule of a larger Germany. Austria’s defeat by Prussia at the Battle of Königgrätz, during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 cleared the way for Prussia to assert control over the rest of Germany. In 1867, the empire was reformed into Austria-Hungary. After the defeat of France in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Austria was left out of the formation of a new German Empire, although in the following decades its politics, and its foreign policy, increasingly converged with those of the Prussian-led Empire. During the 1914 July Crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Germany guided Austria in issuing the ultimatum to Serbia that led to the declaration of World War I.

After the collapse of the Habsburg (Austro-Hungarian) Empire in 1918 at the end of World War I, Austria adopted and used the name the Republic of German-Austria (Deutschösterreich, later Österreich) in an attempt for union with Germany, but was forbidden due to the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919). The First Austrian Republic was established in 1919. In the 1938 Anschluss, Austria was occupied and annexed by Nazi Germany. This lasted until the end of World War II in 1945, after which Germany was occupied by the Allies and Austria’s former democratic constitution was restored. In 1955, the Austrian State Treaty re-established Austria as a sovereign state, ending the occupation. In the same year, the Austrian Parliament created the Declaration of Neutrality which declared that the Second Austrian Republic would become permanently neutral.

Today, Austria is a parliamentary representative democracy comprising nine federal states. The capital and largest city, with a population exceeding 1.7 million, is Vienna. Austria is one of the richest countries in the world, with a nominal per capita GDP of $52,216 (2014 est.). The country has developed a high standard of living and in 2014 was ranked 21st in the world for its Human Development Index. Austria has been a member of the United Nations since 1955, joined the European Union in 1995, and is a founder of the OECD. Austria also signed the Schengen Agreement in 1995, and adopted the euro in 1999.

|

The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair (German: Weltausstellung 1873 Wien) was the large world exposition that was held in 1873 in the Austria-Hungarian capital Vienna. Its motto was “Culture and Education” (Kultur und Erziehung).

The 1873 Vienna World’s Fair (German: Weltausstellung 1873 Wien) was the large world exposition that was held in 1873 in the Austria-Hungarian capital Vienna. Its motto was “Culture and Education” (Kultur und Erziehung). 41 Japanese officials and government interpreters, as well as 6 Europeans in Japanese employ, came to Vienna to oversee the pavilion and the fair’s cultural events. 25 craftsmen and gardeners created the main pavilion, as well as a full Japanese garden with shrine and a model of the former pagoda at Tokyo’s imperial temple.Apart from the collection of regional objects, which focused on ceramics, cloisonné wares, lacquerware, and textiles, the displays also included the female golden shachi from Nagoya Castle and a papier-maché copy of the Kamakura Buddha.The year after the fair, Sano compiled a report on it which ran to 96 volumes divided into 16 parts, including a strong plea for the creation of a museum on western lines in the Japanese capital; the government further began hosting national industrial exhibitions at Ueno Park in 1877.

41 Japanese officials and government interpreters, as well as 6 Europeans in Japanese employ, came to Vienna to oversee the pavilion and the fair’s cultural events. 25 craftsmen and gardeners created the main pavilion, as well as a full Japanese garden with shrine and a model of the former pagoda at Tokyo’s imperial temple.Apart from the collection of regional objects, which focused on ceramics, cloisonné wares, lacquerware, and textiles, the displays also included the female golden shachi from Nagoya Castle and a papier-maché copy of the Kamakura Buddha.The year after the fair, Sano compiled a report on it which ran to 96 volumes divided into 16 parts, including a strong plea for the creation of a museum on western lines in the Japanese capital; the government further began hosting national industrial exhibitions at Ueno Park in 1877. Osman Hamdi Bey, an archaeologist and painter, was chosen by the Ottoman government as commissary of the empire’s exhibits in Vienna. He organized the Ottoman pavilion with Victor Marie de Launay, a French-born Ottoman official and archivist, who had written the catalogue for the Ottoman Empire’s exhibition at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair.The Ottoman pavilion, located near the Egyptian pavilion (which had its own pavilion despite being a territory of the Ottoman Empire),in the park outside the Rotunde, included small replicas of notable Ottoman buildings and models of vernacular architecture: a replica of the Sultan Ahmed Fountain in the Topkapı Palace, a model Istanbul residence, a representative Turkish bath, a cafe, and a bazaar.The 1873 Ottoman pavilion was more prominent than its pavilion in 1867. The Vienna exhibition set off Western nations’

Osman Hamdi Bey, an archaeologist and painter, was chosen by the Ottoman government as commissary of the empire’s exhibits in Vienna. He organized the Ottoman pavilion with Victor Marie de Launay, a French-born Ottoman official and archivist, who had written the catalogue for the Ottoman Empire’s exhibition at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair.The Ottoman pavilion, located near the Egyptian pavilion (which had its own pavilion despite being a territory of the Ottoman Empire),in the park outside the Rotunde, included small replicas of notable Ottoman buildings and models of vernacular architecture: a replica of the Sultan Ahmed Fountain in the Topkapı Palace, a model Istanbul residence, a representative Turkish bath, a cafe, and a bazaar.The 1873 Ottoman pavilion was more prominent than its pavilion in 1867. The Vienna exhibition set off Western nations’  pavilions against Eastern pavilions, with the host, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, setting itself at the juncture between East and West.A report by the Ottoman commission for the exhibition expressed a goal of inspiring with their display “a serious interest Ottoman Empire on the part of the industrialists, traders, artists, and scholars of other nations….”

pavilions against Eastern pavilions, with the host, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, setting itself at the juncture between East and West.A report by the Ottoman commission for the exhibition expressed a goal of inspiring with their display “a serious interest Ottoman Empire on the part of the industrialists, traders, artists, and scholars of other nations….” Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (Franz Joseph Karl; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and monarch of other states in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, from 2 December 1848 to his death. From 1 May 1850 to 24 August 1866 he was also President of the German Confederation. He was the longest-reigning Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, as well as the third-longest-reigning monarch of any country in European history, after Louis XIV of France and Johann II of Liechtenstein.

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (Franz Joseph Karl; 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and monarch of other states in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, from 2 December 1848 to his death. From 1 May 1850 to 24 August 1866 he was also President of the German Confederation. He was the longest-reigning Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, as well as the third-longest-reigning monarch of any country in European history, after Louis XIV of France and Johann II of Liechtenstein.

Austria, officially the Republic of Austria (German: Republik Österreich), is a federal republic and a landlocked country of over 8.5 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Hungary and Slovakia to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the west. The territory of Austria covers 83,879 square kilometres (32,386 sq mi). Austria’s terrain is highly mountainous, lying within the Alps; only 32% of the country is below 500 metres (1,640 ft), and its highest point is 3,798 metres (12,461 ft). The majority of the population speak local Bavarian dialects of German as their native language, and Austrian German in its standard form is the country’s official language. Other local official languages are Hungarian, Burgenland Croatian, and Slovene.

Austria, officially the Republic of Austria (German: Republik Österreich), is a federal republic and a landlocked country of over 8.5 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Hungary and Slovakia to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the west. The territory of Austria covers 83,879 square kilometres (32,386 sq mi). Austria’s terrain is highly mountainous, lying within the Alps; only 32% of the country is below 500 metres (1,640 ft), and its highest point is 3,798 metres (12,461 ft). The majority of the population speak local Bavarian dialects of German as their native language, and Austrian German in its standard form is the country’s official language. Other local official languages are Hungarian, Burgenland Croatian, and Slovene. The origins of modern-day Austria date back to the time of the Habsburg dynasty when the vast majority of the country was a part of the Holy Roman Empire. From the time of the Reformation, many Northern German princes, resenting the authority of the Emperor, used Protestantism as a flag of rebellion. The Thirty Years War, the influence of the Kingdom of Sweden and Kingdom of France, the rise of the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Napoleonic invasions all weakened the power of the Emperor in the North of Germany, but in the South, and in non-German areas of the Empire, the Emperor and Catholicism maintained control. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Austria was able to retain its position as one of the great powers of Europe and, in response to the coronation of Napoleon as the Emperor of the French, the Austrian Empire was officially proclaimed in 1804. Following Napoleon’s defeat, Prussia emerged as Austria’s chief competitor for rule of a larger Germany. Austria’s defeat by Prussia at the Battle of Königgrätz, during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 cleared the way for Prussia to assert control over the rest of Germany. In 1867, the empire was reformed into Austria-Hungary. After the defeat of France in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Austria was left out of the formation of a new German Empire, although in the following decades its politics, and its foreign policy, increasingly converged with those of the Prussian-led Empire. During the 1914 July Crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Germany guided Austria in issuing the ultimatum to Serbia that led to the declaration of World War I.

The origins of modern-day Austria date back to the time of the Habsburg dynasty when the vast majority of the country was a part of the Holy Roman Empire. From the time of the Reformation, many Northern German princes, resenting the authority of the Emperor, used Protestantism as a flag of rebellion. The Thirty Years War, the influence of the Kingdom of Sweden and Kingdom of France, the rise of the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Napoleonic invasions all weakened the power of the Emperor in the North of Germany, but in the South, and in non-German areas of the Empire, the Emperor and Catholicism maintained control. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Austria was able to retain its position as one of the great powers of Europe and, in response to the coronation of Napoleon as the Emperor of the French, the Austrian Empire was officially proclaimed in 1804. Following Napoleon’s defeat, Prussia emerged as Austria’s chief competitor for rule of a larger Germany. Austria’s defeat by Prussia at the Battle of Königgrätz, during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 cleared the way for Prussia to assert control over the rest of Germany. In 1867, the empire was reformed into Austria-Hungary. After the defeat of France in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Austria was left out of the formation of a new German Empire, although in the following decades its politics, and its foreign policy, increasingly converged with those of the Prussian-led Empire. During the 1914 July Crisis that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Germany guided Austria in issuing the ultimatum to Serbia that led to the declaration of World War I.