|

United States of America

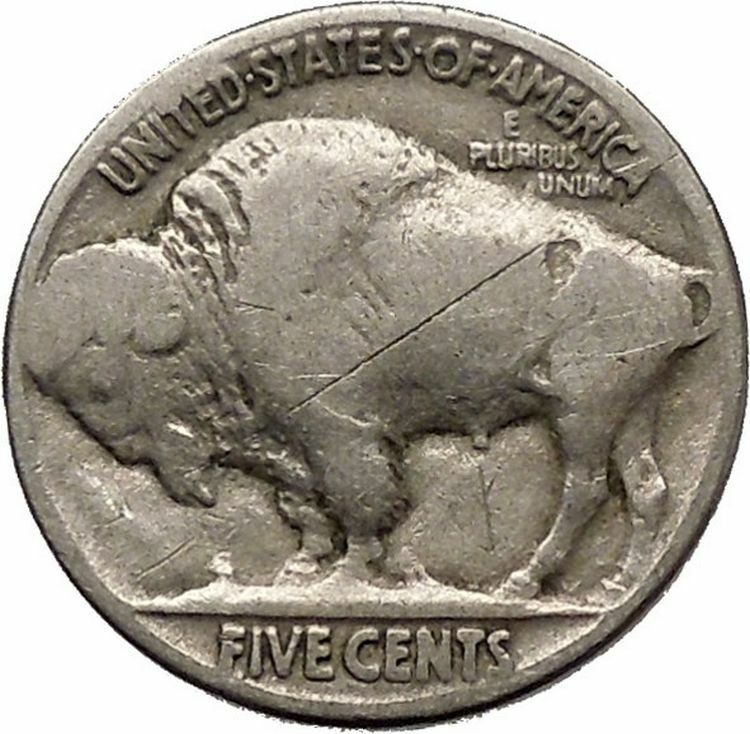

1936 Buffalo Nickel Five Cent Coin 21.21 mm (5.08 grams)

Head of American Indian right, LIBERTY to right, initial of designer, F below date.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA E PLURIBUS UNUM FIVE CENTS, American buffalo standing left.

James Earle Fraser designed this nickel, coming up with design from three models of Native Americans. The bison from New York Central Park zoo called “Black Diamond” is supposedly the model he used for this coin.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel was a copper-nickel five-cent piece struck by the United States Mint from 1913 to 1938. It was designed by sculptor James Earle Fraser .

As part of a drive to beautify the coinage, five denominations of US coins had received new designs between 1907 and 1909. In 1911, Taft administration officials decided to replace Charles E. Barber ‘s Liberty Head design for the nickel, and commissioned Fraser to do the work. They were impressed by Fraser’s designs showing a Native American and an American bison . The designs were approved in 1912, but were delayed several months because of objections from the Hobbs Manufacturing Company, which made mechanisms to detect slugs in nickel-operated machines. The company was not satisfied by changes made in the coin by Fraser, and in February 1913, Treasury Secretary Franklin MacVeagh decided to issue the coins despite the objections.

Despite attempts by the Mint to adjust the design, the coins proved to strike indistinctly, and to be subject to wear—the dates were easily worn away in circulation. In 1938, after the minimum 25-year period during which the design could not be replaced without congressional authorization had expired, it was replaced by the Jefferson nickel designed by Felix Schlag.

The first coins to be distributed were given out on February 22, 1913, when Taft presided at groundbreaking ceremonies for the National American Indian Memorial at Fort Wadsworth , Staten Island, New York . The memorial, a project of department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker , was never built, and today the site is occupied by an abutment for the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge . Forty nickels were sent by the Mint for the ceremony; most were distributed to the Native American chiefs who participated. Payment for Fraser’s work was approved on March 3, 1913, the final full day of the Taft administration. In addition to the $2,500 agreed upon, Fraser received $666.15 (US$15,900 with inflation) for extra work and expenses through February 14.

The coins were officially released to circulation on March 4, 1913, and quickly gained positive comments as depicting truly American themes. However, The New York Times stated in an editorial that “The new ‘nickel’ is a striking example of what a coin intended for wide circulation should not be … is not pleasing to look at when new and shiny, and will be an abomination when old and dull.” The Numismatist , in March and May 1913 editorials, gave the new coin a lukewarm review, suggesting that the Indian’s head be reduced in size and the bison be eliminated from the reverse.

With the coin now in production, Barber monitored the rate at which dies were expended, as it was the responsibility of his Engraver’s Department to supply all three mints with working dies. On March 11, 1913, he wrote to Landis that the dies were being used up three times faster than with the Liberty Head nickel. His department was straining to produce enough new dies to meet production. In addition, the date and denomination were the points on the coin most subject to wear, and Landis feared the value on the coin would be worn away. Barber made proposed revisions, which Fraser approved after being sent samples. These changes enlarged the legend “FIVE CENTS” and changed the ground on which the bison stands from a hill to flat ground. According to data compiled by numismatic historian David Lange from the National Archives , the changes to what are known as Type II nickels (with the originals Type I) actually decreased the die life. The new Treasury Secretary, William G. McAdoo , wanted further changes in the coin, but Fraser had moved on to other projects and was uninterested in revisiting the nickel. The thickness of the numerals in the date was gradually increased, making them more durable; however the problem was never addressed with complete success, and even many later-date Buffalo nickels have the date worn away.

The Buffalo nickel saw minor changes to the design in 1916. The word “LIBERTY” was given more emphasis and moved slightly; however many Denver and San Francisco issues of the 1920s exhibit weak striking of the word, the Denver issue of 1926 especially; Bowers questions whether any change was made to the portrait of the Indian, though Walter Breen in his reference work on United States coins states that Barber made the Indian’s nose slightly longer. According to Breen, however, none of these modifications helped, with the coin rarely found well-struck and with the design subject to considerable wear throughout the remainder of its run. The bison’s horn and tail also posed striking problems, again with the Denver and San Francisco issues of the 1920s in general, and 1926-D in particular, showing the greatest propensity for these deficiencies.

The piece was struck by the tens of millions, at all three mints (Philadelphia, Denver and San Francisco ), through the remainder of the 1910s. In 1921, a recession began, and no nickels at all were struck the following year. The low mintage for the series was the 1926-S, at 970,000 — the only date-mint combination with a mintage of less than 1 million. The second lowest mintage for the series came with the 1931 nickel struck at the San Francisco Mint . The 1931-S was minted in a quantity of 194,000 early in the year. There was no need for more to be struck, but Acting Mint Director Mary Margaret O’Reilly asked the San Francisco Mint to strike more so that the pieces would not be hoarded. Using materials on hand, including the melting down of worn-out nickels, San Francisco found enough metal to strike 1,000,000 more pieces. Large quantities were saved in the hope they would become valuable, and the coin is not particularly rare today despite the low mintage.

A well-known variety in the series is the 1937–D “three-legged” nickel, on which one of the buffalo’s legs is missing. Breen relates that this variety was caused by a pressman, Mr. Young, at the Denver Mint , who in seeking to remove marks from a reverse die (caused by the dies making contact with each other), accidentally removed or greatly weakened one of the animal’s legs. By the time Mint inspectors discovered and condemned the die, thousands of pieces had been struck and mixed with other coins.

Another variety is the 1938-D/S, caused by dies bearing an “S” mintmark being repunched with a “D” and used to strike coins at Denver. While the actual course of events is uncertain, Bowers is convinced that the variety was created because Buffalo nickel dies intended for the San Francisco mint were repunched with the “D” and sent to Denver so they would not be wasted—no San Francisco Buffalo nickels were struck in 1938, but they were produced at Denver, and it was already known that a new design would be introduced. The 1938-D/S was the first repunched mintmark of any US coin to be discovered, causing great excitement among numismatists when the variety came to light in 1962.

When the Buffalo nickel had been in circulation for the minimum 25 years, it was replaced with little discussion or protest. The problems of die life and weak striking had never been solved, and Mint officials advocated its replacement. In January 1938, the Mint announced an open competition for a new nickel design, to feature early President Thomas Jefferson on the obverse, and Jefferson’s home, Monticello on the reverse. In April, Felix Schlag was announced as the winner. The last Buffalo nickels were struck in April 1938, at the Denver Mint, the only mint to strike them that year. On October 3, 1938, production of the Jefferson nickel began, and they were released into circulation on November 15.

Design, models, and name controversy

In a 1947 radio interview, Fraser discussed his design:

Well, when I was asked to do a nickel, I felt I wanted to do something totally American—a coin that could not be mistaken for any other country’s coin. It occurred to me that the buffalo, as part of our western background, was 100% American, and that our North American Indian fitted into the picture perfectly.

The visage of the Indian which dominates Fraser’s obverse design was a composite of several Native Americans. Breen noted (before the advent of the Sacagawea dollar ) that Fraser’s design was the second and last US coin design to feature a realistic portrait of an Indian, after Bela Pratt ‘s 1908 design for the half eagle and quarter eagle .

The identity of the Indians whom Fraser used as models is somewhat uncertain,

as Fraser told various and not always consistent stories during the forty years

he lived after designing the nickel. In December 1913, he wrote to Mint Director

Roberts that ” before the nickel was made I had done several portraits of Indians, among them Iron Tail , Two Moons , and one or two others, and probably got characteristics from those men in the head on the coins, but my purpose was not to make a portrait but a type.”

By 1931, Two Guns White Calf, son of the last Blackfoot tribal chief, was capitalizing off his claim to be the model for the coin. To try to put an end to the claim, Fraser wrote that he had used three Indians for the piece, including “Iron Tail, the best Indian head I can remember. The other one was Two Moons, the other I cannot recall.” In 1938, Fraser stated that the three Indians had been “Iron Tail, a Sioux, Big Tree , a Kiowa, and Two Moons , a Cheyenne”. Despite the sculptor’s efforts, he (and the Mint) continued to receive inquiries about the identity of the Indian model until his 1953 death.

Nevertheless, John Big Tree , a Seneca , claimed to be a model for Fraser’s coin, and made many public appearances as the “nickel Indian” until his 1967 death at the age of 92 (though he sometimes alleged he was over 100 years of age). Big Tree was identified as the model for the nickel in wire service reports about his death, and he had appeared in that capacity at the Texas Numismatic Association convention in 1966. After Big Tree ‘s death, the Mint stated that he most likely was not one of the models for the nickel. There have been other claimants: in 1964, Montana Senator Mike Mansfield wrote to Mint Director Eva B. Adams , enquiring if Sam Resurrection, a Choctaw was a model for the nickel. Adams wrote in reply, “According to our records, the portrait is a composite. There have been many claimants for this honor, all of whom are undoubtedly sincere in the belief that theirs is the one that adorns the nickel.”

According to Fraser, the animal that appears on the reverse is the American bison Black Diamond . In an interview published in the New York Herald on January 27, 1913, Fraser was quoted as saying that the animal, which he did not name, was a “typical and shaggy specimen” which he found at the Bronx Zoo . Fraser later wrote that the model “was not a plains buffalo, but none other than Black Diamond, the contrariest animal in the Bronx Zoo. I stood for hours … He refused point blank to permit me to get side views of him, and stubbornly showed his front face most of the time.” However, Black Diamond was never at the Bronx Zoo, but instead lived at the Central Park Zoo until he was sold and slaughtered in 1915. Black Diamond’s mounted head is still extant, and has been exhibited at coin conventions. The placement of Black Diamond’s horns differs considerably from that of the animal on the nickel, leading to doubts that Black Diamond was Fraser’s model. One candidate cited by Bowers is Bronx, a bison who was for many years the herd leader of the bison at the Bronx Zoo.

From its inception, the coin was referred to as the “Buffalo nickel”, reflecting the American colloquialism for the North American bison. As the piece is 75% copper and 25% nickel, prominent numismatist Stuart Mosher objected to the nomenclature in the 1940s, writing that he was “uncertain why it is called a ‘Buffalo nickel’ although the name is preferable to ‘Bison copper'”. The numismatic publication with the greatest circulation, Coin World , calls it an Indian head nickel, while R.S. Yeoman ‘s Red Book refers to it as an “Indian Head or Buffalo type”.

In 2001, the design was adopted for use on a commemorative silver dollar. In 2006, the Mint began striking American Buffalo gold bullion pieces, using a modification of Fraser’s Type I design.

|