|

Portugal

400th Anniversary of “Os Lusiadas”

1972 Silver 50 Escudos 34mm (18.03 grams) 0.650 Silver (0.3762 oz. ASW)

Reference: KM# 602

REPVBLICA·PORTVGVESA *50·ESCVDOS*, Book appears as part of Quinas Cross, all within circle.

victory within design flanked by dates, all within circle.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

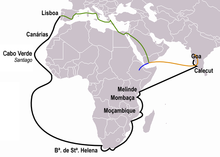

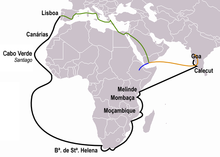

Os Lusíadas (Portuguese pronunciation: [uʒ luˈzi.ɐðɐʃ]), usually translated as The Lusiads, is a Portuguese epic poem written by Luís Vaz de Camões (c. 1524/5 – 1580) and first published in 1572. It is widely regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature and is frequently compared to Virgil’s Aeneid (1st c. BC). The work celebrates the discovery of a sea route to India by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama (1469-1524). The ten cantos of the poem are in ottava rima and total 1,102 stanzas. Os Lusíadas (Portuguese pronunciation: [uʒ luˈzi.ɐðɐʃ]), usually translated as The Lusiads, is a Portuguese epic poem written by Luís Vaz de Camões (c. 1524/5 – 1580) and first published in 1572. It is widely regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature and is frequently compared to Virgil’s Aeneid (1st c. BC). The work celebrates the discovery of a sea route to India by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama (1469-1524). The ten cantos of the poem are in ottava rima and total 1,102 stanzas.

Written in Homeric fashion, the poem focuses mainly on a fantastical interpretation of the Portuguese voyages of discovery during the 15th and 16th centuries. Os Lusíadas is often regarded as Portugal’s national epic, much as Virgil’s Aeneid was for the Ancient Romans, or Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey for the Ancient Greeks. It was written when Camões was an exile in Macau and was first printed in 1572, three years after the author returned from the Indies.

The poem consists of ten cantos, each with a different number of stanzas (1102 in total). It is written in the decasyllabic ottava rima, which has the rhyme scheme ABABABCC, and contains a total of 8816 lines of verse.

The poem is made up of four sections:

- An introduction (proposition – presentation of the theme and heroes of the poem)

- Invocation – a prayer to the Tágides, the nymphs of the Tagus;

- A dedication – (to Sebastian of Portugal)

- Narration (the epic itself) – starting in stanza 19 of canto I, in media res, starting in the midst of the action, with the background story being told later in the epic.

The narration concludes with an epilogue, starting in stanza 145 of canto X. The most important part of Os Lusíadas, the arrival in India, was placed at the point in the poem that divides the work according to the golden section at the beginning of Canto VII.

The heroes

The heroes of the epic are the Lusiads (Lusíadas), the sons of Lusus-in other words, the Portuguese. The initial strophes of Jupiter’s speech in the Concílio dos Deuses Olímpicos (Council of the Olympian Gods), which open the narrative part, highlight the laudatory orientation of the author.

In these strophes, Camões speaks of Viriatus and Quintus Sertorius, the people of Lusus, a people predestined by the Fates to accomplish great deeds. Jupiter says that their history proves it because, having emerged victorious against the Moors and Castilians, this tiny nation has gone on to discover new worlds and impose its law in the concert of the nations. At the end of the poem, on the Island of Love, the fictional finale to the glorious tour of Portuguese history, Camões writes that the fear once expressed by Bacchus has been confirmed: that the Portuguese would become gods.

The extraordinary Portuguese discoveries and the “new kingdom that they exalted so much” (“novo reino que tanto sublimaram“) in the East, and certainly the recent and extraordinary deeds of the “strong Castro” (“Castro forte“, the viceroy Dom João de Castro), who had died some years before the poet’s arrival to Indian lands, were the decisive factors in Camões’ completion of the Portuguese epic. Camões dedicated his masterpiece to King Sebastian of Portugal.

The narrators and their speeches

The vast majority of the narration in Os Lusíadas consists of grandiloquent speeches by various orators: the main narrator; Vasco da Gama, recognized as “eloquent captain” (“facundo capitão“); Paulo da Gama; Thetis; and the Siren who tells the future in Canto X. The poet asks the Tágides (nymphs of the river Tagus) to give him “a high and sublime sound,/ a grandiloquent and flowing style” (“um som alto e sublimado, / Um estilo grandíloquo e corrente“). In contrast to the style of lyric poetry, or “humble verse” (“verso humilde“), he is thinking about this exciting tone of oratory. There are in the poem some speeches that are brief but notable, including Jupiter’s and the Old Man of the Restelo’s.

There are also descriptive passages, like the description of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim of Calicute, the locus amoenus of the Island of Love (Canto IX), the dinner in the palace of Thetis (Canto X), and Gama’s cloth (end of Canto II). Sometimes these descriptions are like a slide show, in which someone shows each of the things described there; examples include the geographic start of Gama’s speech to the king of Melinde, certain sculptures of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim, the speech of Paulo da Gama to the Catual, and the Machine of the World (Máquina do Mundo). There are also descriptive passages, like the description of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim of Calicute, the locus amoenus of the Island of Love (Canto IX), the dinner in the palace of Thetis (Canto X), and Gama’s cloth (end of Canto II). Sometimes these descriptions are like a slide show, in which someone shows each of the things described there; examples include the geographic start of Gama’s speech to the king of Melinde, certain sculptures of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim, the speech of Paulo da Gama to the Catual, and the Machine of the World (Máquina do Mundo).

Examples of dynamic descriptions include the “battle” of the Island of Mozambique, the battles of Ourique and Aljubarrota, and the storm. Camões is a master in these descriptions, marked by the verbs of movement, the abundance of visual and acoustic sensations, and expressive alliterations. There are also many lyrical moments. Those texts are normally narrative-descriptive. This is the case with the initial part of the episode of the Sad Inês, the final part of the episode of the Adamastor, and the encounter on the Island of Love (Canto IX). All these cases resemble eclogues.

On several occasions the poet assumes a tone of lamentation, as at the end of Canto I, in parts of the speech of the Old Man of the Restelo, the end of Canto V, the beginning and end of Canto VII, and the final strophes of the poem. Many times, da Gama bursts into oration at challenging moments: in Mombasa (Canto II), on the appearance of Adamastor, and in the middle of the terror of the storm. The poet’s invocations to the Tágides and nymphs of Mondego (Cantos I and VII) and to Calliope (beginning of Cantos III and X), in typological terms, are also orations. Each one of these types of speech shows stylistic peculiarities.

Synopses of Cantos

Canto I

The epic begins with a dedication section, with the poet paying homage to Virgil and Homer. The first line mimics the opening line of the Aeneid, and pays a hopeful tribute to the young King Sebastião. The story, then (in imitation of the classical epics) portrays the gods of Greece watching over the voyage of Vasco da Gama. Just as the gods had divided loyalties during the voyages of Odysseus and Aeneas, here Venus, who favors the Portuguese, is opposed by Bacchus, who is here associated with the east and resents the encroachment on his territory. We encounter Vasco da Gama’s voyage in medias res as they have already rounded the Cape of Good Hope. At the urging of Bacchus, who is disguised as a Moor, the local Muslims plot to attack the explorer and his crew.

Canto II

Two scouts sent by Vasco da Gama are fooled by a fake altar created by Bacchus into thinking that there are Christians among the Muslims. Thus, the explorers are lured into an ambush but successfully survive with the aid of Venus. Venus pleads with her father Jove, who predicts great fortunes for the Portuguese in the east. The fleet lands at Melinde where it is welcomed by a friendly Sultan.

Canto III

After an appeal by the poet to Calliope, the Greek muse of epic poetry, Vasco da Gama begins to narrate the history of Portugal. He starts by referring to the situation of Portugal in Europe and the legendary story of Lusus and Viriathus. This is followed by passages on the meaning of Portuguese nationality and then by an enumeration of the warrior deeds of the 1st Dynasty kings, from Dom Afonso Henriques to Dom Fernando. Episodes that stand out include Egas Moniz and the Battle of Ourique during Dom Afonso Henriques’ reign, formosíssima Maria (the beautiful Maria) in the Battle of Salado, and Inês de Castro during Dom Afonso IV’s reign. After an appeal by the poet to Calliope, the Greek muse of epic poetry, Vasco da Gama begins to narrate the history of Portugal. He starts by referring to the situation of Portugal in Europe and the legendary story of Lusus and Viriathus. This is followed by passages on the meaning of Portuguese nationality and then by an enumeration of the warrior deeds of the 1st Dynasty kings, from Dom Afonso Henriques to Dom Fernando. Episodes that stand out include Egas Moniz and the Battle of Ourique during Dom Afonso Henriques’ reign, formosíssima Maria (the beautiful Maria) in the Battle of Salado, and Inês de Castro during Dom Afonso IV’s reign.

Canto IV

Vasco da Gama continues the narrative of the history of Portugal by recounting the story of the House of Aviz from the 1383-85 Crisis until the moment during the reign of Dom Manuel I when the armada of Vasco da Gama sails to India. The narrative of the Crisis of 1383-85, which focuses mainly on the figure of Nuno Álvares Pereira and the Battle of Aljubarrota, is followed by the events of the reigns of Dom João II, especially those related to expansion into Africa.

Following this incident, the poem narrates the maritime journey to India-an aim that Dom João II did not accomplish during his lifetime, but would come true with Dom Manuel, to whom the rivers Indus and Ganges appeared in dreams foretelling the future glories of the Orient. This canto ends with the sailing of the Armada, the sailors in which are surprised by the prophetically pessimistic words of an old man who was on the beach among the crowd. This is the episode of the Old Man of the Restelo.

Canto V

The story moves on to the King of Melinde, describing the journey of the Armada from Lisbon to Melinde. During the voyage, the sailors see the Southern Cross, St. Elmo’s Fire (maritime whirlwind), and face a variety of dangers and obstacles such as the hostility of natives in the episode of Fernão Veloso, the fury of a monster in the episode of the giant Adamastor, and the disease and death caused by scurvy. Canto V ends with the poet’s censure of his contemporaries who despise poetry.

Canto VI

After Vasco da Gama’s narrative, the armada sails from Melinde guided by a pilot to teach them the way to Calicut. Bacchus, seeing that the Portuguese are about to arrive in India, asks for help of Neptune, who convenes a “Concílio dos Deuses Marinhos” (Council of the Sea Gods) whose decision is to support Bacchus and unleash powerful winds to sink the armada. Then, while the sailors are listening to Fernão Veloso telling the legendary and chivalrous episode of Os Doze de Inglaterra (The Twelve Men of England), a storm strikes.

Vasco da Gama, seeing the near destruction of his caravels, prays to his own God, but it is Venus who helps the Portuguese by sending the Nymphs to seduce the winds and calm them down. After the storm, the armada sights Calicut, and Vasco da Gama gives thanks to God. The canto ends with the poet speculating about the value of the fame and glory reached through great deeds.

Canto VII

After condemning some of the other nations of Europe (who in his opinion fail to live up to Christian ideals), the poet tells of the Portuguese fleet reaching the Indian city of Calicut. A Muslim named Monçaide greets the fleet and tells the explorers about the lands they have reached. The king, Samorin, hears of the newcomers and summons them. A governor and official of the king, called the Catual, leads the Portuguese to the king, who receives them well. The Catual speaks with Monçaide to learn more about the new arrivals. The Catual then goes to the Portuguese ships himself to confirm what Monsayeed has told him and is treated well.

Canto VIII

The Catual sees a number of paintings that depict significant figures and events from Portuguese history, all of which are detailed by the author. Bacchus appears in a vision to a Muslim priest in Samorin’s court and convinces him that the explorers are a threat. The priest spreads the warnings among the Catuals and the court, prompting Samorin to confront da Gama on his intentions. Da Gama insists that the Portuguese are traders, not buccaneers. The king then demands proof from da Gama’s ships, but when he tries to return to the fleet, da Gama finds that the Catual, who has been corrupted by the Muslim leaders, refuses to lend him a boat at the harbor and holds him prisoner. Da Gama manages to get free only after agreeing to have all of the goods on the ships brought to shore to be sold.

Canto IX

The Muslims plot to detain the Portuguese until the annual trading fleet from Mecca can arrive to attack them, but Monçaide tells da Gama of the conspiracy, and the ships escape from Calicut. To reward the explorers for their efforts, Venus prepares an island for them to rest on and asks her son Cupid to inspire Nereids with desire for them. When the sailors arrive on the Isle of Love, the ocean nymphs make a pretense of running but surrender quickly.

Canto X

During a sumptuous feast on the Isle of Love, Tethys, who is now the lover of da Gama, prophecies the future of Portuguese exploration and conquest. She tells of Duarte Pacheco Pereira’s defense of Cochin (Battle of Cochin); the Battle of Diu fought by Francisco de Almeida and his son Lourenço de Almeida against combined Gujarati-Egyptian fleets; the deeds of Tristão da Cunha, Pedro de Mascarenhas, Lopo Vaz de Sampaio and Nuno da Cunha; and battles fought by Martim Afonso de Sousa and João de Castro. Tethys then guides da Gama to a summit and reveals to him a vision of how the (Ptolemaic) universe operates. The tour continues with glimpses of the lands of Africa and Asia. The legend of the martyrdom of the apostle St. Thomas in India is told at this point. Finally, Tethys relates the voyage of Magellan. The epic concludes with more advice to young King Sebastião.

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: República Portuguesa), is a country on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe. It is the westernmost country of mainland Europe, being bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and south and by Spain to the north and east. The Portugal-Spain border is 1,214 km (754 mi) long and considered the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union. The republic also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, both autonomous regions with their own regional governments. Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: República Portuguesa), is a country on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe. It is the westernmost country of mainland Europe, being bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and south and by Spain to the north and east. The Portugal-Spain border is 1,214 km (754 mi) long and considered the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union. The republic also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, both autonomous regions with their own regional governments.

The territory of modern Portugal has been continuously settled, invaded and fought over since prehistoric times. The Pre-Celts, Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and the Romans were followed by the invasions of the Visigothic and the Suebi Germanic peoples, who were themselves later invaded by the Moors. These Muslim peoples were eventually expelled during the Christian Reconquista. Portuguese nationality can be traced back to the creation of the First County of Portugal, in 868. In 1139, Afonso Henriques was proclaimed King of Portugal, thus firmly establishing Portuguese independence, under the Portuguese House of Burgundy. The territory of modern Portugal has been continuously settled, invaded and fought over since prehistoric times. The Pre-Celts, Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and the Romans were followed by the invasions of the Visigothic and the Suebi Germanic peoples, who were themselves later invaded by the Moors. These Muslim peoples were eventually expelled during the Christian Reconquista. Portuguese nationality can be traced back to the creation of the First County of Portugal, in 868. In 1139, Afonso Henriques was proclaimed King of Portugal, thus firmly establishing Portuguese independence, under the Portuguese House of Burgundy.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, under the House of Aviz, which took power following the 1383-85 Crisis, Portugal expanded Western influence and established the first global empire, becoming one of the world’s major economic, political and military powers. During this time, Portuguese explorers pioneered maritime exploration in the Age of Discovery, notably under royal patronage of Prince Henry the Navigator and King João II, with such notable discoveries as Vasco da Gama’s sea route to India (1497-98), Pedro Álvares Cabral’s discovery of Brazil (1500), and Bartolomeu Dias’s reaching of the Cape of Good Hope. Portugal monopolized the spice trade during this time, under royal command of the Casa da Índia, and the Portuguese Empire expanded with military campaigns led in Asia, notably under Afonso de Albuquerque, who was known as the “Caesar of the East”.

The destruction of Lisbon in a 1755 earthquake, the country’s occupation during the Napoleonic Wars, the independence of Brazil (1822), and the Liberal Wars (1828-1834), all left Portugal crippled from war and diminished in its world power. After the 1910 revolution deposed the monarchy, the democratic but unstable Portuguese First Republic was established, later being superseded by the “Estado Novo” right-wing authoritarian regime. Democracy was restored after the Portuguese Colonial War and the Carnation Revolution in 1974. Shortly after, independence was granted to all its colonies and East Timor, with the exception of Macau, which was handed over to China in 1999. This marked the end of the longest-lived European colonial empire, leaving a profound cultural and architectural influence across the globe and a legacy of over 250 million Portuguese speakers today.

Portugal is a developed country with a high-income advanced economy and high living standards. It is the 5th most peaceful country in the world, maintaining a unitary semi-presidential republican form of government. It has the 18th highest Social Progress in the world, putting it ahead of other Western European countries like France, Spain and Italy. It is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations, the European Union, the eurozone, OECD, NATO and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries. Portugal is also known for having decriminalized the usage of all common drugs in 2001, the first country in the world to do so. However, the sale and distribution of these drugs is still illegal in Portugal.

|

Os Lusíadas (Portuguese pronunciation: [uʒ luˈzi.ɐðɐʃ]), usually translated as The Lusiads, is a Portuguese epic poem written by Luís Vaz de Camões (c. 1524/5 – 1580) and first published in 1572. It is widely regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature and is frequently compared to Virgil’s Aeneid (1st c. BC). The work celebrates the discovery of a sea route to India by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama (1469-1524). The ten cantos of the poem are in ottava rima and total 1,102 stanzas.

Os Lusíadas (Portuguese pronunciation: [uʒ luˈzi.ɐðɐʃ]), usually translated as The Lusiads, is a Portuguese epic poem written by Luís Vaz de Camões (c. 1524/5 – 1580) and first published in 1572. It is widely regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature and is frequently compared to Virgil’s Aeneid (1st c. BC). The work celebrates the discovery of a sea route to India by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama (1469-1524). The ten cantos of the poem are in ottava rima and total 1,102 stanzas.  There are also descriptive passages, like the description of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim of Calicute, the locus amoenus of the Island of Love (Canto IX), the dinner in the palace of Thetis (Canto X), and Gama’s cloth (end of Canto II). Sometimes these descriptions are like a slide show, in which someone shows each of the things described there; examples include the geographic start of Gama’s speech to the king of Melinde, certain sculptures of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim, the speech of Paulo da Gama to the Catual, and the Machine of the World (Máquina do Mundo).

There are also descriptive passages, like the description of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim of Calicute, the locus amoenus of the Island of Love (Canto IX), the dinner in the palace of Thetis (Canto X), and Gama’s cloth (end of Canto II). Sometimes these descriptions are like a slide show, in which someone shows each of the things described there; examples include the geographic start of Gama’s speech to the king of Melinde, certain sculptures of the palaces of Neptune and the Samorim, the speech of Paulo da Gama to the Catual, and the Machine of the World (Máquina do Mundo).  After an appeal by the poet to Calliope, the Greek muse of epic poetry, Vasco da Gama begins to narrate the history of Portugal. He starts by referring to the situation of Portugal in Europe and the legendary story of Lusus and Viriathus. This is followed by passages on the meaning of Portuguese nationality and then by an enumeration of the warrior deeds of the 1st Dynasty kings, from Dom Afonso Henriques to Dom Fernando. Episodes that stand out include Egas Moniz and the Battle of Ourique during Dom Afonso Henriques’ reign, formosíssima Maria (the beautiful Maria) in the Battle of Salado, and Inês de Castro during Dom Afonso IV’s reign.

After an appeal by the poet to Calliope, the Greek muse of epic poetry, Vasco da Gama begins to narrate the history of Portugal. He starts by referring to the situation of Portugal in Europe and the legendary story of Lusus and Viriathus. This is followed by passages on the meaning of Portuguese nationality and then by an enumeration of the warrior deeds of the 1st Dynasty kings, from Dom Afonso Henriques to Dom Fernando. Episodes that stand out include Egas Moniz and the Battle of Ourique during Dom Afonso Henriques’ reign, formosíssima Maria (the beautiful Maria) in the Battle of Salado, and Inês de Castro during Dom Afonso IV’s reign.

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: República Portuguesa), is a country on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe. It is the westernmost country of mainland Europe, being bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and south and by Spain to the north and east. The Portugal-Spain border is 1,214 km (754 mi) long and considered the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union. The republic also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, both autonomous regions with their own regional governments.

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic (Portuguese: República Portuguesa), is a country on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe. It is the westernmost country of mainland Europe, being bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and south and by Spain to the north and east. The Portugal-Spain border is 1,214 km (754 mi) long and considered the longest uninterrupted border within the European Union. The republic also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, both autonomous regions with their own regional governments. The territory of modern Portugal has been continuously settled, invaded and fought over since prehistoric times. The Pre-Celts, Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and the Romans were followed by the invasions of the Visigothic and the Suebi Germanic peoples, who were themselves later invaded by the Moors. These Muslim peoples were eventually expelled during the Christian Reconquista. Portuguese nationality can be traced back to the creation of the First County of Portugal, in 868. In 1139, Afonso Henriques was proclaimed King of Portugal, thus firmly establishing Portuguese independence, under the Portuguese House of Burgundy.

The territory of modern Portugal has been continuously settled, invaded and fought over since prehistoric times. The Pre-Celts, Celts, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and the Romans were followed by the invasions of the Visigothic and the Suebi Germanic peoples, who were themselves later invaded by the Moors. These Muslim peoples were eventually expelled during the Christian Reconquista. Portuguese nationality can be traced back to the creation of the First County of Portugal, in 868. In 1139, Afonso Henriques was proclaimed King of Portugal, thus firmly establishing Portuguese independence, under the Portuguese House of Burgundy.