|

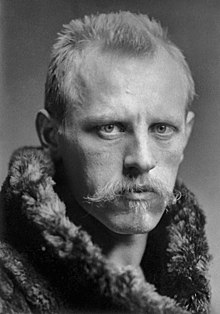

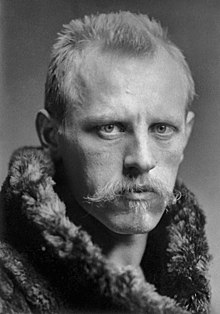

Cook Islands – Great Explorers Series – Fridtjof Nansen

1988 Silver 50 Dollars 38mm (19.15 grams) 0.925 Silver (0.6227 oz. ASW)

Reference: KM# 108

ELIZABETH II COOK ISLANDS RDM 1988, Effigy of queen Elizabeth II facing right, date below.

FRIDTJOF NANSEN $50 FM, Fridtjof Nansen, with ship to right.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Fridtjof Nansen (Norwegian: [²fɾɪtːjɔf ˈnɑnsn̩]; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth he was a champion skier and ice skater. He led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, traversing the island on cross-country skis. He won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°14′ during his Fram expedition of 1893-1896. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions. Fridtjof Nansen (Norwegian: [²fɾɪtːjɔf ˈnɑnsn̩]; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth he was a champion skier and ice skater. He led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, traversing the island on cross-country skis. He won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°14′ during his Fram expedition of 1893-1896. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.

Nansen studied zoology at the Royal Frederick University in Christiania and later worked as a curator at the University Museum of Bergen where his research on the central nervous system of lower marine creatures earned him a doctorate and helped establish neuron doctrine. Later, famed neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal would win the 1906 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his research on the same subject, though “technical priority” for the theory is given to Nansen. After 1896 his main scientific interest switched to oceanography; in the course of his research he made many scientific cruises, mainly in the North Atlantic, and contributed to the development of modern oceanographic equipment. As one of his country’s leading citizens, in 1905 Nansen spoke out for the ending of Norway’s union with Sweden, and was instrumental in persuading Prince Carl of Denmark to accept the throne of the newly independent Norway. Between 1906 and 1908 he served as the Norwegian representative in London, where he helped negotiate the Integrity Treaty that guaranteed Norway’s independent status.

In the final decade of his life, Nansen devoted himself primarily to the League of Nations, following his appointment in 1921 as the League’s High Commissioner for Refugees. In 1922 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on behalf of the displaced victims of the First World War and related conflicts. Among the initiatives he introduced was the “Nansen passport” for stateless persons, a certificate that used to be recognised by more than 50 countries. He worked on behalf of refugees until his sudden death in 1930, after which the League established the Nansen International Office for Refugees to ensure that his work continued. This office received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938. His name is commemorated in numerous geographical features, particularly in the polar regions.

Expedition

The sealer Jason picked up Nansen’s party on 3 June 1888 from the Icelandic port of Ísafjörður. They sighted the Greenland coast a week later, but thick pack ice hindered progress. With the coast still 20 kilometres (12 mi) away, Nansen decided to launch the small boats. They were within sight of Sermilik Fjord on 17 July; Nansen believed it would offer a route up the icecap. The sealer Jason picked up Nansen’s party on 3 June 1888 from the Icelandic port of Ísafjörður. They sighted the Greenland coast a week later, but thick pack ice hindered progress. With the coast still 20 kilometres (12 mi) away, Nansen decided to launch the small boats. They were within sight of Sermilik Fjord on 17 July; Nansen believed it would offer a route up the icecap.

The expedition left Jason “in good spirits and with the highest hopes of a fortunate result.” Days of extreme frustration followed as they drifted south. Weather and sea conditions prevented them from reaching the shore. They spent most time camping on the ice itself-it was too dangerous to launch the boats.

By 29 July, they found themselves 380 kilometres (240 mi) south of the point where they left the ship. That day they finally reached land but were too far south to begin the crossing. Nansen ordered the team back into the boats after a brief rest and to begin rowing north. The party battled northward along the coast through the ice floes for the next 12 days. They encountered a large Eskimo encampment on the first day, near Cape Steen Bille. Occasional contacts with the nomadic native population continued as the journey progressed.

The party reached Umivik Bay on 11 August, after covering 200 kilometres (120 mi). Nansen decided they needed to begin the crossing. Although they were still far south of his intended starting place; the season was becoming too advanced. After they landed at Umivik, they spent the next four days preparing for their journey. They set out on the evening of 15 August, heading north-west towards Christianhaab on the western shore of Disko Bay-600 kilometres (370 mi) away.

Over the next few days, the party struggled to ascend. The inland ice had a treacherous surface with many hidden crevasses and the weather was bad. Progress stopped for three days because of violent storms and continuous rain one time. The last ship was due to leave Christianhaab by mid-September. They would not be able to reach it in time, Nansen concluded on 26 August. He ordered a change of course due west, towards Godthaab; a shorter journey by at least 150 kilometres (93 mi). The rest of the party, according to Nansen, “hailed the change of plan with acclamation.”

They continued climbing until 11 September and reached a height of 2,719 metres (8,921 ft) above sea level. Temperatures on the icecap summit of the icecap dropped to −45 °C (−49 °F) at night. From then on the downward slope made travelling easier. Yet, the terrain was rugged and the weather remained hostile. Progress was slow: fresh snowfalls made dragging the sledges like pulling them through sand.

On 26 September, they battled their way down the edge of a fjord westward towards Godthaab. Sverdrup constructed a makeshift boat out of parts of the sledges, willows, and their tent. Three days later, Nansen and Sverdrup began the last stage of the journey; rowing down the fjord.

On 3 October, they reached Godthaab, where the Danish town representative greeted them. He first informed Nansen that he secured his doctorate, a matter that “could not have been more remote from [Nansen’s] thoughts at that moment.” The team accomplished their crossing in 49 days. Throughout the journey, they maintained meteorological and geographical and other records relating to the previously unexplored interior.

The rest of the team arrived in Godthaab on 12 October. Nansen soon learned no ship was likely to call at Godthaab until the following spring. Still, they were able to send letters back to Norway via a boat leaving Ivigtut at the end of October. He and his party spent the next seven months in Greenland. On 15 April 1889, the Danish ship Hvidbjørnen finally entered the harbour. Nansen recorded: “It was not without sorrow that we left this place and these people, among whom we had enjoyed ourselves so well.”

With the ship’s latitude at 84°4′N and after two false starts, Nansen and Johansen began their journey on 14 March 1895. Nansen allowed 50 days to cover the 356 nautical miles (660 km; 410 mi) to the pole, an average daily journey of seven nautical miles (13 km; 8 mi). After a week of travel, a sextant observation indicated they averaged nine nautical miles (17 km; 10 mi) per day, which put them ahead of schedule. However, uneven surfaces made skiing more difficult, and their speeds slowed. They also realised they were marching against a southerly drift, and that distances travelled did not necessarily equate to distance progressed.

On 3 April, Nansen began to doubt whether the pole was attainable. Unless their speed improved, their food would not last them to the pole and back to Franz Josef Land. He confided in his diary: “I have become more and more convinced we ought to turn before time.” Four days later, after making camp, he observed the way ahead was “… a veritable chaos of iceblocks stretching as far as the horizon.” Nansen recorded their latitude as 86°13′6″N-almost three degrees beyond the previous record-and decided to turn around and head back south.

At first Nansen and Johansen made good progress south, but suffered a serious setback on 13 April, when in his eagerness to break camp, he had forgotten to wind both of their chronometers, which made it impossible to calculate their longitude and accurately navigate to Franz Josef Land. They restarted the watches based on Nansen’s guess they were at 86°E. From then on were uncertain of their true position. The tracks of an Arctic fox were observed towards the end of April. It was the first trace of a living creature other than their dogs since they left Fram. They soon saw bear tracks and by the end of May saw evidence of nearby seals, gulls and whales. At first Nansen and Johansen made good progress south, but suffered a serious setback on 13 April, when in his eagerness to break camp, he had forgotten to wind both of their chronometers, which made it impossible to calculate their longitude and accurately navigate to Franz Josef Land. They restarted the watches based on Nansen’s guess they were at 86°E. From then on were uncertain of their true position. The tracks of an Arctic fox were observed towards the end of April. It was the first trace of a living creature other than their dogs since they left Fram. They soon saw bear tracks and by the end of May saw evidence of nearby seals, gulls and whales.

On 31 May, Nansen calculated they were only 50 nautical miles (93 km; 58 mi) from Cape Fligely, Franz Josef Land’s northernmost point. Travel conditions worsened as increasingly warmer weather caused the ice to break up. On 22 June, the pair decided to rest on a stable ice floe while they repaired their equipment and gathered strength for the next stage of their journey. They remained on the floe for a month.

The day after leaving this camp, Nansen recorded: “At last the marvel has come to pass-land, land, and after we had almost given up our belief in it!” Whether this still-distant land was Franz Josef Land or a new discovery they did not know-they had only a rough sketch map to guide them. The edge of the pack ice was reached on 6 August and they shot the last of their dogs-the weakest of which they killed regularly to feed the others since 24 April. The two kayaks were lashed together, a sail was raised, and they made for the land.

It soon became clear this land was part of an archipelago. As they moved southwards, Nansen tentatively identified a headland as Cape Felder on the western edge of Franz Josef Land. Towards the end of August, as the weather grew colder and travel became increasingly difficult, Nansen decided to camp for the winter. In a sheltered cove, with stones and moss for building materials, the pair erected a hut which was to be their home for the next eight months. With ready supplies of bear, walrus and seal to keep their larder stocked, their principal enemy was not hunger but inactivity. After muted Christmas and New Year celebrations, in slowly improving weather, they began to prepare to leave their refuge, but it was 19 May 1896 before they were able to resume their journey.

Rescue and return

On 17 June, during a stop for repairs after the kayaks had been attacked by a walrus, Nansen thought he heard a dog barking as well as human voices. He went to investigate, and a few minutes later saw the figure of a man approaching. It was the British explorer Frederick Jackson, who was leading an expedition to Franz Josef Land and was camped at Cape Flora on nearby Northbrook Island. The two were equally astonished by their encounter; after some awkward hesitation Jackson asked: “You are Nansen, aren’t you?”, and received the reply “Yes, I am Nansen.”

Johansen was picked up and the pair were taken to Cape Flora where, during the following weeks, they recuperated from their ordeal. Nansen later wrote that he could “still scarcely grasp” their sudden change of fortune; had it not been for the walrus attack that caused the delay, the two parties might have been unaware of each other’s existence.

On 7 August, Nansen and Johansen boarded Jackson’s supply ship Windward, and sailed for Vardø where they arrived on the 13th. They were greeted by Hans Mohn, the originator of the polar drift theory, who was in the town by chance. The world was quickly informed by telegram of Nansen’s safe return, but as yet there was no news of Fram.

Taking the weekly mail steamer south, Nansen and Johansen reached Hammerfest on 18 August, where they learned that Fram had been sighted. She had emerged from the ice north and west of Spitsbergen, as Nansen had predicted, and was now on her way to Tromsø. She had not passed over the pole, nor exceeded Nansen’s northern mark. Without delay Nansen and Johansen sailed for Tromsø, where they were reunited with their comrades.

The homeward voyage to Christiania was a series of triumphant receptions at every port. On 9 September, Fram was escorted into Christiania’s harbour and welcomed by the largest crowds the city had ever seen. The crew were received by King Oscar, and Nansen, reunited with family, remained at the palace for several days as special guests. Tributes arrived from all over the world; typical was that from the British mountaineer Edward Whymper, who wrote that Nansen had made “almost as great an advance as has been accomplished by all other voyages in the nineteenth century put together”.

Nansen died of a heart attack on 13 May 1930. He was given a non-religious state funeral before cremation, after which his ashes were laid under a tree at Polhøgda. Nansen’s daughter Liv recorded that there were no speeches, just music: Schubert’s Death and the Maiden, which Eva used to sing.

The Cook Islands (Cook Islands Māori: Kūki ‘Āirani) is a self-governing island country in the South Pacific Ocean in free association with New Zealand. It comprises 15 islands whose total land area is 240 square kilometres (92.7 sq mi). The Cook Islands’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers 1,800,000 square kilometres (690,000 sq mi) of ocean. The Cook Islands (Cook Islands Māori: Kūki ‘Āirani) is a self-governing island country in the South Pacific Ocean in free association with New Zealand. It comprises 15 islands whose total land area is 240 square kilometres (92.7 sq mi). The Cook Islands’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers 1,800,000 square kilometres (690,000 sq mi) of ocean.

New Zealand is responsible for the Cook Islands’ defence and foreign affairs, but they are exercised in consultation with the Cook Islands. In recent times, the Cook Islands have adopted an increasingly independent foreign policy. Although Cook Islanders are citizens of New Zealand, they have the status of Cook Islands nationals, which is not given to other New Zealand citizens.

.svg/250px-Cook_Islands_on_the_globe_(Polynesia_centered).svg.png) The Cook Islands’ main population centres are on the island of Rarotonga (10,572 in 2011), where there is an international airport. There is a larger population of Cook Islanders in New Zealand itself; in the 2013 census, 61,839 people said they were Cook Islanders, or of Cook Islands descent. The Cook Islands’ main population centres are on the island of Rarotonga (10,572 in 2011), where there is an international airport. There is a larger population of Cook Islanders in New Zealand itself; in the 2013 census, 61,839 people said they were Cook Islanders, or of Cook Islands descent.

With about 100,000 visitors travelling to the islands in the 2010-11 financial year, tourism is the country’s main industry, and the leading element of the economy, ahead of offshore banking, pearls, and marine and fruit exports.

|

Fridtjof Nansen (Norwegian: [²fɾɪtːjɔf ˈnɑnsn̩]; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth he was a champion skier and ice skater. He led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, traversing the island on cross-country skis. He won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°14′ during his Fram expedition of 1893-1896. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.

Fridtjof Nansen (Norwegian: [²fɾɪtːjɔf ˈnɑnsn̩]; 10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth he was a champion skier and ice skater. He led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, traversing the island on cross-country skis. He won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°14′ during his Fram expedition of 1893-1896. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.  The sealer Jason picked up Nansen’s party on 3 June 1888 from the Icelandic port of Ísafjörður. They sighted the Greenland coast a week later, but thick pack ice hindered progress. With the coast still 20 kilometres (12 mi) away, Nansen decided to launch the small boats. They were within sight of Sermilik Fjord on 17 July; Nansen believed it would offer a route up the icecap.

The sealer Jason picked up Nansen’s party on 3 June 1888 from the Icelandic port of Ísafjörður. They sighted the Greenland coast a week later, but thick pack ice hindered progress. With the coast still 20 kilometres (12 mi) away, Nansen decided to launch the small boats. They were within sight of Sermilik Fjord on 17 July; Nansen believed it would offer a route up the icecap.  At first Nansen and Johansen made good progress south, but suffered a serious setback on 13 April, when in his eagerness to break camp, he had forgotten to wind both of their chronometers, which made it impossible to calculate their longitude and accurately navigate to Franz Josef Land. They restarted the watches based on Nansen’s guess they were at 86°E. From then on were uncertain of their true position. The tracks of an Arctic fox were observed towards the end of April. It was the first trace of a living creature other than their dogs since they left Fram. They soon saw bear tracks and by the end of May saw evidence of nearby seals, gulls and whales.

At first Nansen and Johansen made good progress south, but suffered a serious setback on 13 April, when in his eagerness to break camp, he had forgotten to wind both of their chronometers, which made it impossible to calculate their longitude and accurately navigate to Franz Josef Land. They restarted the watches based on Nansen’s guess they were at 86°E. From then on were uncertain of their true position. The tracks of an Arctic fox were observed towards the end of April. It was the first trace of a living creature other than their dogs since they left Fram. They soon saw bear tracks and by the end of May saw evidence of nearby seals, gulls and whales.  The Cook Islands (Cook Islands Māori: Kūki ‘Āirani) is a self-governing island country in the South Pacific Ocean in free association with New Zealand. It comprises 15 islands whose total land area is 240 square kilometres (92.7 sq mi). The Cook Islands’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers 1,800,000 square kilometres (690,000 sq mi) of ocean.

The Cook Islands (Cook Islands Māori: Kūki ‘Āirani) is a self-governing island country in the South Pacific Ocean in free association with New Zealand. It comprises 15 islands whose total land area is 240 square kilometres (92.7 sq mi). The Cook Islands’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers 1,800,000 square kilometres (690,000 sq mi) of ocean.

.svg/250px-Cook_Islands_on_the_globe_(Polynesia_centered).svg.png) The Cook Islands’ main population centres are on the island of Rarotonga (10,572 in 2011), where there is an international airport. There is a larger population of Cook Islanders in New Zealand itself; in the 2013 census, 61,839 people said they were Cook Islanders, or of Cook Islands descent.

The Cook Islands’ main population centres are on the island of Rarotonga (10,572 in 2011), where there is an international airport. There is a larger population of Cook Islanders in New Zealand itself; in the 2013 census, 61,839 people said they were Cook Islanders, or of Cook Islands descent.