|

China – Northern Dynasties – Northern Zhou (557-581)

Wu: Emperor 561-578 AD

Bronze Bu Quan Cash Token 26mm, Struck 561-578 AD

Reference: H# 13.29

Chinese Symbols.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The Northern Zhou (/dʒoʊ/; Chinese: 北周; pinyin: Bĕi Zhōu) followed the Western Wei, and ruled northern China from 557 to 581 AD. The last of the Northern Dynasties of China’s Northern and Southern dynasties period, it was eventually overthrown by the Sui Dynasty. Like the preceding Western and Northern Wei dynasties, the Northern Zhou emperors were of Xianbei descent. The Northern Zhou (/dʒoʊ/; Chinese: 北周; pinyin: Bĕi Zhōu) followed the Western Wei, and ruled northern China from 557 to 581 AD. The last of the Northern Dynasties of China’s Northern and Southern dynasties period, it was eventually overthrown by the Sui Dynasty. Like the preceding Western and Northern Wei dynasties, the Northern Zhou emperors were of Xianbei descent.

The Northern Zhou’s basis of power was established by Yuwen Tai, who was paramount general of Western Wei, following the split of Northern Wei into Western Wei and Eastern Wei in 535. After Yuwen Tai’s death in 556, Yuwen Tai’s nephew Yuwen Hu forced Emperor Gong of Western Wei to yield the throne to Yuwen Tai’s son Yuwen Jue (Emperor Xiaomin), establishing Northern Zhou. The reigns of the first three emperors (Yuwen Tai’s sons) – Emperor Xiaomin, Emperor Ming, and Emperor Wu were dominated by Yuwen Hu, until Emperor Wu ambushed and killed Yuwen Hu in 572 and assumed power personally. With Emperor Wu as a capable ruler, Northern Zhou destroyed rival Northern Qi in 577, taking over Northern Qi’s territory. However, Emperor Wu’s death in 578 doomed the state, as his son Emperor Xuan was an arbitrary and violent ruler whose unorthodox behavior greatly weakened the state. After his death in 580, when he was already nominally retired (Taishang Huang), Xuan’s father-in-law Yang Jian took power, and in 581 seized the throne from Emperor Xuan’s son Emperor Jing, establishing Sui. The young Emperor Jing and the imperial Yuwen clan, were subsequently slaughtered by Yang Jian.

The area was known as Guannei 關內. The Northern Zhou drew upon the Zhou dynasty for inspiration. The Northern Zhou military included Han Chinese.

The Northern dynasties began when the Northern Wei conquered the Northern Liang to unite northern China and ended in 589 when Sui dynasty extinguished the Chen dynasty. It can be divided into three time periods: Northern Wei; Eastern and Western Weis; Northern Qi and Northern Zhou. The Northern, Eastern, and Western Wei along with the Northern Zhou were established by the Xianbei people while the Northern Qi was established by Sinicized barbarians. The Northern dynasties began when the Northern Wei conquered the Northern Liang to unite northern China and ended in 589 when Sui dynasty extinguished the Chen dynasty. It can be divided into three time periods: Northern Wei; Eastern and Western Weis; Northern Qi and Northern Zhou. The Northern, Eastern, and Western Wei along with the Northern Zhou were established by the Xianbei people while the Northern Qi was established by Sinicized barbarians.

In the north, local Han Chinese gentry clans had consolidated themselves by constructing fortified villages. A clan would carve out a de facto fief through a highly cohesive family-based self-defense community. Lesser peasant families would work for the dominant clan as tenants or serfs. This was a response to the chaotic political environment, and these Han Chinese gentry families largely avoided government service before the Northern Wei court launched the sinicization movement. The northern gentry was therefore highly militarized as compared to the refined southern aristocrats, and this distinction persisted well into the Sui and Tang dynasties centuries later.

Rise of Northern Wei (386–535) and the Sinicization movement

In the Sixteen Kingdoms period, the Tuoba family of the Xianbei were the rulers of the state of Dai (Sixteen Kingdoms). Although it was conquered by the Former Qin, the defeat of the Former Qin at the Battle of Fei River resulted in the collapse of the Former Qin. The grandson of the last prince of Dai Tuoba Shiyijian, Tuoba Gui restored the fortunes of the Tuoba clan, renaming his state Wei (now known as Northern Wei) with its capital at Shengle (near modern Hohhot). Under the rule of Emperors Daowu (Tuoba Gui), Mingyuan, and Taiwu, the Northern Wei progressively expanded. The establishment of the early Northern Wei state and the economy were also greatly indebted to the father-son pair of Cui Hong and Cui Hao. Tuoba Gui engaged in numerous conflicts with the Later Yan that ended favorably for the Northern Wei after they received help from Zhang Gun that allowed them to destroy the Later Yan army at the Battle of Canhe Slope. Following this victory, Tuoba Gui conquered the Later Yan capital of Pingcheng (modern-day Datong). That same year he declared himself Emperor Daowu.

Due to Emperor Daowu’s cruelty, he was killed by his son Tuoba Shao, but crown prince Tuoba Si managed to defeat Tuoba Shao and took the throne as Emperor Mingyuan. Though he managed to conquer Liu Song’s province of Henan, he died soon afterward. Emperor Mingyuan’s son Tuoba Tao took the throne as Emperor Taiwu. Due to Emperor Taiwu’s energetic efforts, Northern Wei’s strength greatly increased, allowing them to repeatedly attack Liu Song. After dealing with the Rouran threat to his northern flank, he engaged in a war to unite northern China. With the fall of the Northern Liang in 439, Emperor Taiwu united northern China, ending the Sixteen Kingdoms period and beginning the Northern and Southern dynasties period with their southern rivals, the Liu Song.

Even though it was a time of great military strength for the Northern Wei, because of Rouran harassment in the north, they could not fully focus on their southern expeditions. After uniting the north, Emperor Taiwu also conquered the strong Shanshan kingdom and subjugated the other kingdoms of Xiyu, or the Western Regions. In 450, Emperor Taiwu once again attacked the Liu Song and reached Guabu (瓜步, in modern Nanjing, Jiangsu), threatening to cross the river to attack Jiankang, the Liu Song capital. Though up to this point, the Northern Wei military forces dominated the Liu Song forces, they took heavy casualties. The Northern Wei forces plundered numerous households before returning north.

At this point, followers of the Buddhist Gai Wu (蓋吳) rebelled. After pacifying this rebellion, Emperor Taiwu, under the advice of his Daoist prime minister Cui Hao, proscribed Buddhism, in the first of the Three Disasters of Wu. At this late stage in his life, Emperor Taiwu meted out cruel punishments, which led to his death in 452 at the hands of the eunuch Zong Ai. This sparked off turmoil that only ended with the ascension of Emperor Wencheng later that same year.

In the first half of the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534), the Xianbei steppe tribesmen who dominated northern China kept a policy of strict social distinction between them and their Chinese subjects. Chinese were drafted into the bureaucracy, employed as officials to collect taxes, etc. However, the Chinese were kept out of many higher positions of power. They also represented the minority of the populace where centers of power were located.

In 446 an ethnic Qiang rebellion was crushed by the Northern Wei. Wang Yu (王遇) was an ethnic Qiang eunuch and he may have been castrated during the rebellion since the Northern Wei would castrated the rebel tribe’s young elite. Fengyi prefecture’s Lirun town according to the Weishu was where Wang Yu was born , Lirun was to Xi’ans’s northeast by 100 miles and modern day Chengcheng stands at it’s site. Wang Yu patronized Buddhism and in 488 had a temple constructed in his birth place.

Widespread social and cultural transformation in northern China came with Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei (reigned 471–499), whose father was a Xianbei, but whose mother was Chinese. Although of the Tuoba Clan from the Xianbei tribe, Emperor Xiaowen asserted his dual Xianbei-Chinese identity, renaming his own clan after the Chinese Yuan (元 meaning “elemental” or “origin”). In the year 493 Emperor Xiaowen instituted a new signification program that had the Xianbei elites conform to many Chinese standards. These social reforms included donning Chinese clothing (banning Xianbei clothing at court), learning the Chinese language (if under the age of thirty), applied one-character Chinese surnames to Xianbei families, and encouraged the clans of high-ranking Xianbei and Chinese families to intermarry. Emperor Xiaowen also moved the capital city from Pingcheng to one of China’s old imperial sites, Luoyang, which had been the capital during the earlier Eastern Han and Western Jin dynasties. The new capital at Luoyang was revived and transformed, with roughly 150,000 Xianbei and other northern warriors moved from north to south to fill new ranks for the capital by the year 495. Within a couple of decades, the population rose to about half a million residents and was famed for being home to over a thousand Buddhist temples. Defectors from the south, such as Wang Su of the prestigious Langye Wang family, were largely accommodated and felt at home with the establishment of their own Wu quarter in Luoyang (this quarter of the city was home to over three thousand families). They were even served tea (by this time gaining popularity in southern China) at court instead of yogurt drinks commonly found in the north.

In the year 523, Prince Dongyang of the Northern Wei was sent to Dunhuang to serve as its governor for a term of fifteen years. With the religious force of Buddhism gaining mainstream acceptance in Chinese society, Prince Dongyang and local wealthy families set out to establish a monumental project in honor of Buddhism, carving and decorating Cave 285 of the Mogao Caves with beautiful statues and murals. This promotion of the arts would continue for centuries at Dunhuang and is now one of China’s greatest tourist attractions. In the year 523, Prince Dongyang of the Northern Wei was sent to Dunhuang to serve as its governor for a term of fifteen years. With the religious force of Buddhism gaining mainstream acceptance in Chinese society, Prince Dongyang and local wealthy families set out to establish a monumental project in honor of Buddhism, carving and decorating Cave 285 of the Mogao Caves with beautiful statues and murals. This promotion of the arts would continue for centuries at Dunhuang and is now one of China’s greatest tourist attractions.

The Northern Wei started to arrange for Han Chinese elites to marry daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba royal family in the 480s. More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Han Chinese men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei. Some Han Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Han Chinese elites, the Liu Song royal Liu Hui (刘辉), married Princess Lanling (蘭陵公主) of the Northern Wei, Princess Huayang (華陽公主) to Sima Fei (司馬朏), a descendant of Jin dynasty (266–420) royalty, Princess Jinan (濟南公主) to Lu Daoqian (盧道虔), Princess Nanyang (南阳长公主) to Xiao Baoyin (萧宝夤), a member of Southern Qi royalty. Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei’s sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to The Liang dynasty ruler Emperor Wu of Liang’s son Xiao Zong 蕭綜. One of Emperor Xiaowu of Northern Wei’s sisters was married to Zhang Huan, a Han Chinese, according to the Book of Zhou (Zhoushu). His name is given as Zhang Xin in the Book of Northern Qi (Bei Qishu) and History of the Northern Dynasties (Beishi) which mention his mariage to a Xianbei princess of Wei. His personal name was changed due to a naming taboo on the emperor’s name. He was the son of Zhang Qiong.

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi (司馬楚之) as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong (司馬金龍). Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian’s daughter married Sima Jinlong.

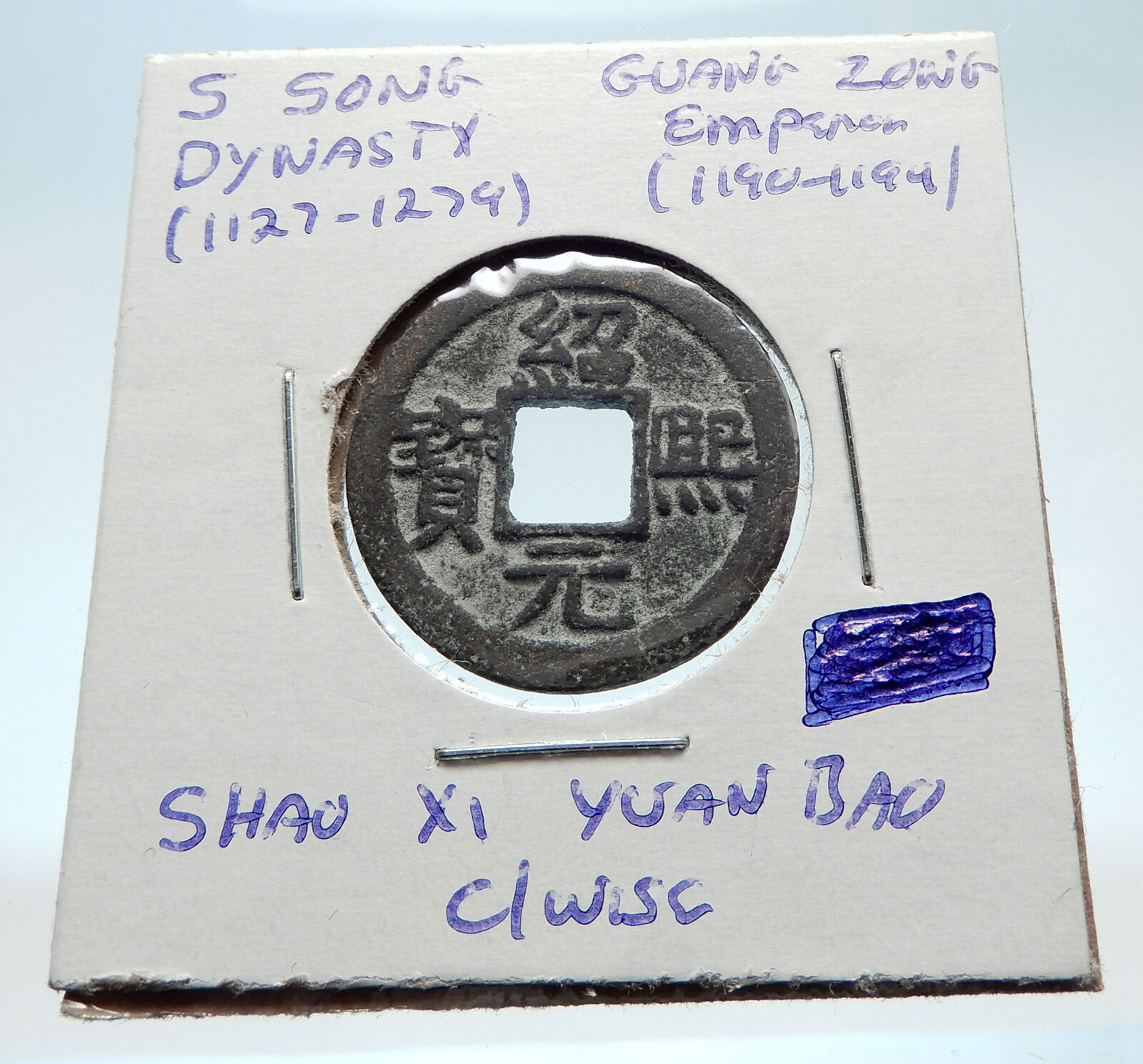

Cash was a type of coin of China and East Asia, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD. Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China as well as under Mongol, and Manchu rule. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast but, during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century.

In the modern era, these coins are considered to be Chinese “good luck coins”; they are hung on strings and round the necks of children, or over the beds of sick people. They hold a place in various superstitions, as well as Traditional Chinese medicine, and Feng shui. Currencies based on the Chinese cash coins include the Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn.

|

The Northern Zhou (/dʒoʊ/; Chinese: 北周; pinyin: Bĕi Zhōu) followed the Western Wei, and ruled northern China from 557 to 581 AD. The last of the Northern Dynasties of China’s Northern and Southern dynasties period, it was eventually overthrown by the Sui Dynasty. Like the preceding Western and Northern Wei dynasties, the Northern Zhou emperors were of Xianbei descent.

The Northern Zhou (/dʒoʊ/; Chinese: 北周; pinyin: Bĕi Zhōu) followed the Western Wei, and ruled northern China from 557 to 581 AD. The last of the Northern Dynasties of China’s Northern and Southern dynasties period, it was eventually overthrown by the Sui Dynasty. Like the preceding Western and Northern Wei dynasties, the Northern Zhou emperors were of Xianbei descent. The Northern dynasties began when the Northern Wei conquered the Northern Liang to unite northern China and ended in 589 when Sui dynasty extinguished the Chen dynasty. It can be divided into three time periods: Northern Wei; Eastern and Western Weis; Northern Qi and Northern Zhou. The Northern, Eastern, and Western Wei along with the Northern Zhou were established by the Xianbei people while the Northern Qi was established by Sinicized barbarians.

The Northern dynasties began when the Northern Wei conquered the Northern Liang to unite northern China and ended in 589 when Sui dynasty extinguished the Chen dynasty. It can be divided into three time periods: Northern Wei; Eastern and Western Weis; Northern Qi and Northern Zhou. The Northern, Eastern, and Western Wei along with the Northern Zhou were established by the Xianbei people while the Northern Qi was established by Sinicized barbarians.

In the year 523, Prince Dongyang of the Northern Wei was sent to Dunhuang to serve as its governor for a term of fifteen years. With the religious force of Buddhism gaining mainstream acceptance in Chinese society, Prince Dongyang and local wealthy families set out to establish a monumental project in honor of Buddhism, carving and decorating Cave 285 of the Mogao Caves with beautiful statues and murals. This promotion of the arts would continue for centuries at Dunhuang and is now one of China’s greatest tourist attractions.

In the year 523, Prince Dongyang of the Northern Wei was sent to Dunhuang to serve as its governor for a term of fifteen years. With the religious force of Buddhism gaining mainstream acceptance in Chinese society, Prince Dongyang and local wealthy families set out to establish a monumental project in honor of Buddhism, carving and decorating Cave 285 of the Mogao Caves with beautiful statues and murals. This promotion of the arts would continue for centuries at Dunhuang and is now one of China’s greatest tourist attractions.