|

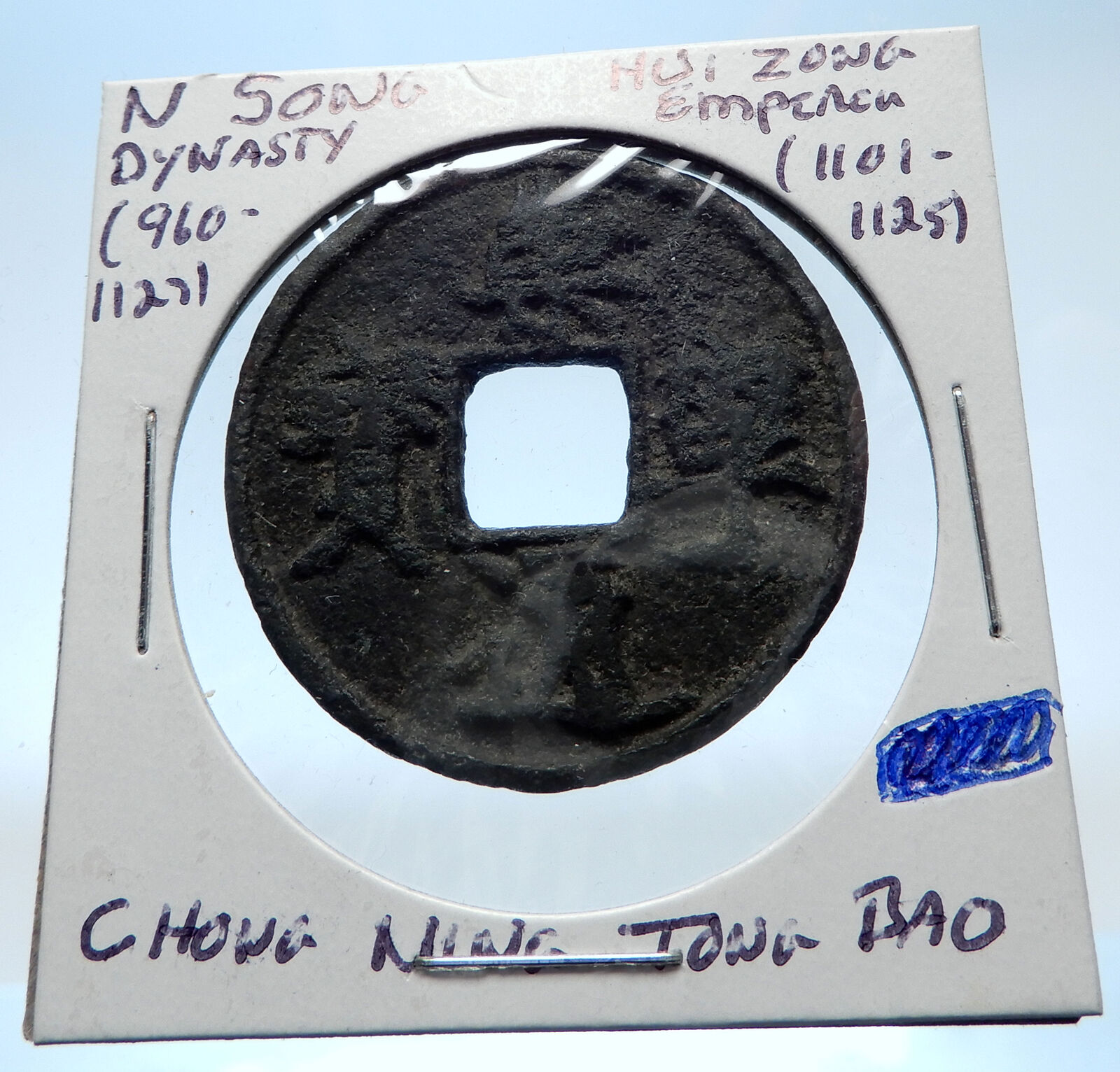

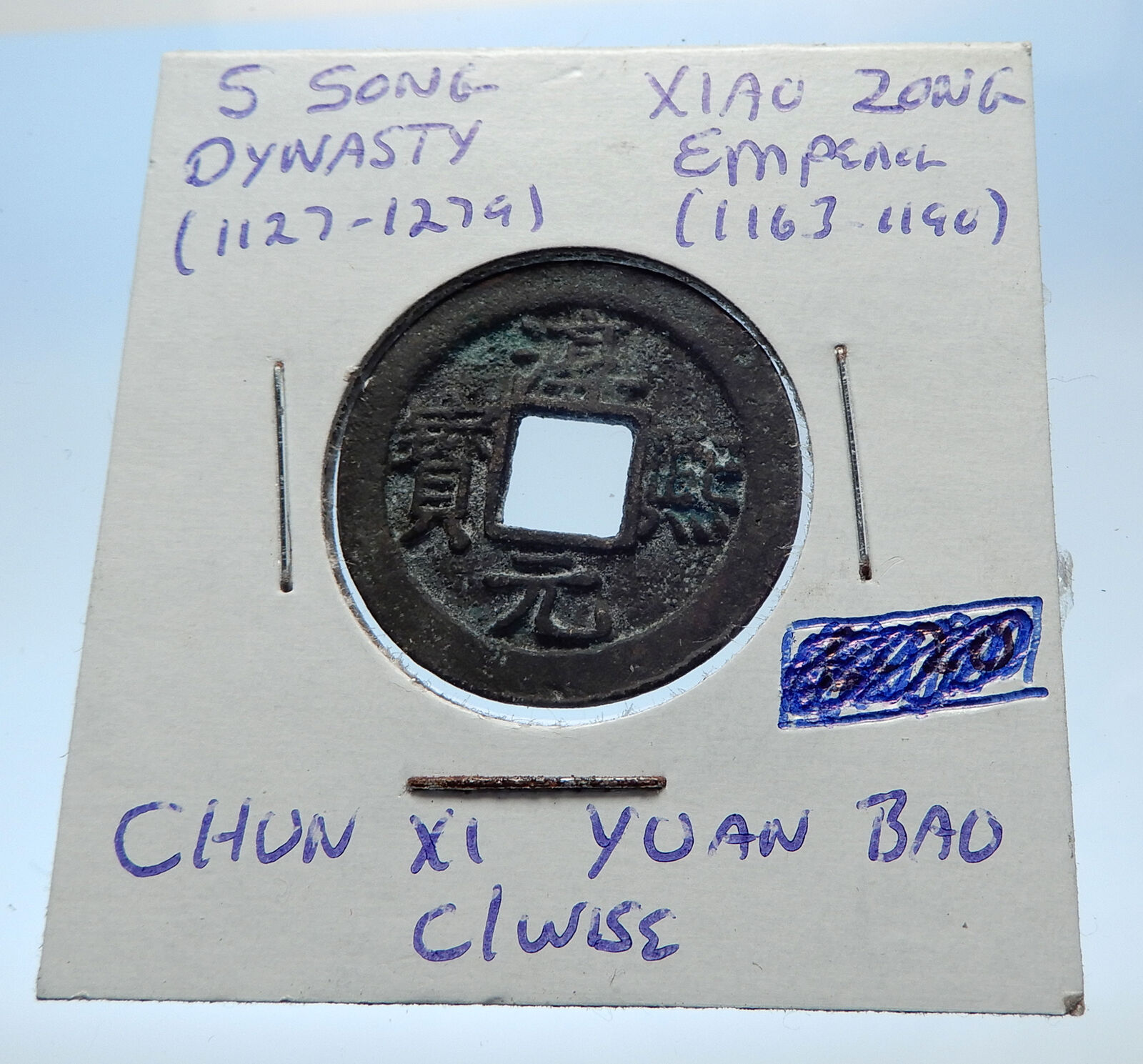

China – Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.)

Wu Zong – Emperor: 845-846 AD

Bronze Tai Yuan Tong Bao Cash 22mm, Struck

845-846

AD

Reference: H# 14.50

開元通寶, Four Chinese characters, square hole within.

No shoulder. Chang, Huichang Period Tithe.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Emperor Wuzong of Tang (July 2, 814 – April 22, 846), né Li Chan, later changed to Li Yan just before his death, was an emperor of the Tang Dynasty of China, reigning from 840 to 846. Emperor Wuzong is mainly known in modern times for the religious persecution that occurred during his reign. However, he was also known for his successful reactions against incursions by remnants of the Uyghur Khanate and the rebellion by Liu Zhen, as well as his deep trust and support for chancellor Li Deyu. Emperor Wuzong of Tang (July 2, 814 – April 22, 846), né Li Chan, later changed to Li Yan just before his death, was an emperor of the Tang Dynasty of China, reigning from 840 to 846. Emperor Wuzong is mainly known in modern times for the religious persecution that occurred during his reign. However, he was also known for his successful reactions against incursions by remnants of the Uyghur Khanate and the rebellion by Liu Zhen, as well as his deep trust and support for chancellor Li Deyu.

After the Zhaoyi campaign, Li Deyu used the opportunity to carry reprisals against his political enemies in the Niu-Li Factional Struggles—those who were members of what would later be referred to as the Niu Faction (named after Niu Sengru) against Li Deyu’s Li Faction—including the former chancellors Niu Sengru and Li Zongmin—by accusing them of complicity in Liu Zhen’s rebellion. As a result, Niu and Li Zongmin were exiled to remote regions.

In 845, Emperor Wuzong wanted to create his favorite concubine, Consort Wang, empress. Li Deyu, pointing out that Consort Wang was of low birth and that she was sonless, opposed. Emperor Wuzong therefore did not do so. (Emperor Wuzong had five known sons, but very little is known about them other than their names and their princely titles.)

Late in Emperor Wuzong’s life, he began taking pills made by Taoist alchemists, which were intended to lead to immortality, and it was said that his mood became harsh and unpredictable as a side effect. By late 845, he was seriously ill. In early 846, in an attempt to ward off the illness, he changed his name to Li Yan—under the theory that under the Wu Xing cosmology, his original name of Chan (瀍) contained two instances of earth (土) while only containing one instance of water (水), which meant that he was getting suppressed by the dynasty’s own spirits (as Tang beliefs included that the dynasty was protected by earth), while Yan (炎) contained two instances of fire (火), which was more harmonious with earth. Despite this change, his conditions did not get better. The eunuchs, believing that Emperor Wuzong’s uncle Li Yi the Prince of Guang to be simple-minded, decided to make him Emperor Wuzong’s successor; they therefore had an edict issued in Emperor Wuzong’s name creating Li Yi crown prince (and changing Li Yi’s name to Li Chen). Soon thereafter, Emperor Wuzong died, and Li Chen took the throne as Emperor Xuānzong.

The The

Tang dynasty (Chinese: 唐朝) or the Tang

Empire was an imperial dynasty of China,

preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Historians generally regard the Tang as a high

point in Chinese civilization, and a golden age

of cosmopolitan culture. Tang territory,

acquired through the military campaigns of its

early rulers, rivaled that of the Han dynasty.

The Tang capital at Chang’an (present-day Xi’an)

was the most populous city in the world in its

day.

The Lǐ family (李) founded the

dynasty, seizing power during the decline and

collapse of the Sui Empire. The dynasty was

briefly interrupted when Empress Wu Zetian

seized the throne, proclaiming the Second Zhou

dynasty (690-705) and becoming the only Chinese

empress regnant. In two censuses of the 7th and

8th centuries, the Tang records estimated the

population by number of registered households at

about 50 million people. Yet, even when the

central government was breaking down and unable

to compile an accurate census of the population

in the 9th century, it is estimated that the

population had grown by then to about 80 million

people.[9][10][b] With its large

population base, the dynasty was able to raise

professional and conscripted armies of hundreds

of thousands of troops to contend with nomadic

powers in dominating Inner Asia and the

lucrative trade-routes along the Silk Road.

Various kingdoms and states paid tribute to the

Tang court, while the Tang also conquered or

subdued several regions which it indirectly

controlled through a protectorate system.

Besides political hegemony, the Tang also

exerted a powerful cultural influence over

neighboring East Asian states such as those in

Japan and Korea.

The Tang dynasty was

largely a period of progress and stability in

the first half of the dynasty’s rule, until the

An Lushan Rebellion and the decline of central

authority in the later half of the dynasty. Like

the previous Sui dynasty, the Tang dynasty

maintained a civil-service system by recruiting

scholar-officials through standardized

examinations and recommendations to office. The

rise of regional military governors known as

jiedushi during the 9th century undermined

this civil order. Chinese culture flourished and

further matured during the Tang era; it is

traditionally considered the greatest age for

Chinese poetry. Two of China’s most famous

poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, belonged to this age,

as did many famous painters such as Han Gan,

Zhang Xuan, and Zhou Fang. Scholars of this

period compiled a rich variety of historical

literature, as well as encyclopedias and

geographical works. The adoption of the title

Tängri Qaghan by the Tang Emperor Taizong in

addition to his title as emperor was eastern

Asia’s first “simultaneous kingship”.

Many notable innovations occurred under the

Tang, including the development of woodblock

printing. Buddhism became a major influence in

Chinese culture, with native Chinese sects

gaining prominence. However, in the 840s the

Emperor Wuzong of Tang enacted policies to

persecute Buddhism, which subsequently declined

in influence. Although the dynasty and central

government had gone into decline by the 9th

century, art and culture continued to flourish.

The weakened central government largely withdrew

from managing the economy, but the country’s

mercantile affairs stayed intact and commercial

trade continued to thrive regardless. However,

agrarian rebellions in the latter half of the

9th century resulted in damaging atrocities such

as the Guangzhou massacre of 878-879.

|

Emperor Wuzong of Tang (July 2, 814 – April 22, 846), né Li Chan, later changed to Li Yan just before his death, was an emperor of the Tang Dynasty of China, reigning from 840 to 846. Emperor Wuzong is mainly known in modern times for the religious persecution that occurred during his reign. However, he was also known for his successful reactions against incursions by remnants of the Uyghur Khanate and the rebellion by Liu Zhen, as well as his deep trust and support for chancellor Li Deyu.

Emperor Wuzong of Tang (July 2, 814 – April 22, 846), né Li Chan, later changed to Li Yan just before his death, was an emperor of the Tang Dynasty of China, reigning from 840 to 846. Emperor Wuzong is mainly known in modern times for the religious persecution that occurred during his reign. However, he was also known for his successful reactions against incursions by remnants of the Uyghur Khanate and the rebellion by Liu Zhen, as well as his deep trust and support for chancellor Li Deyu. The

The