|

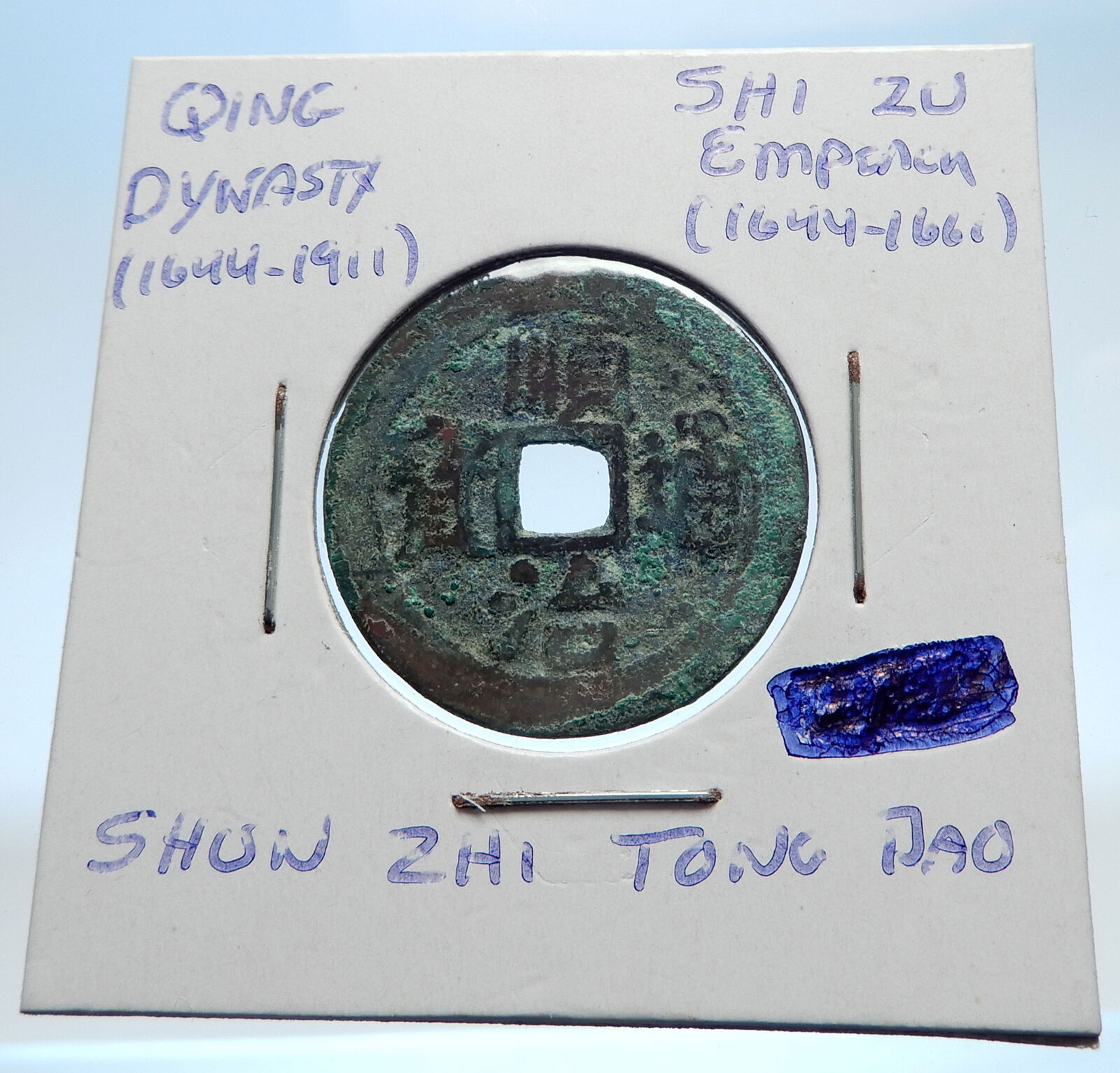

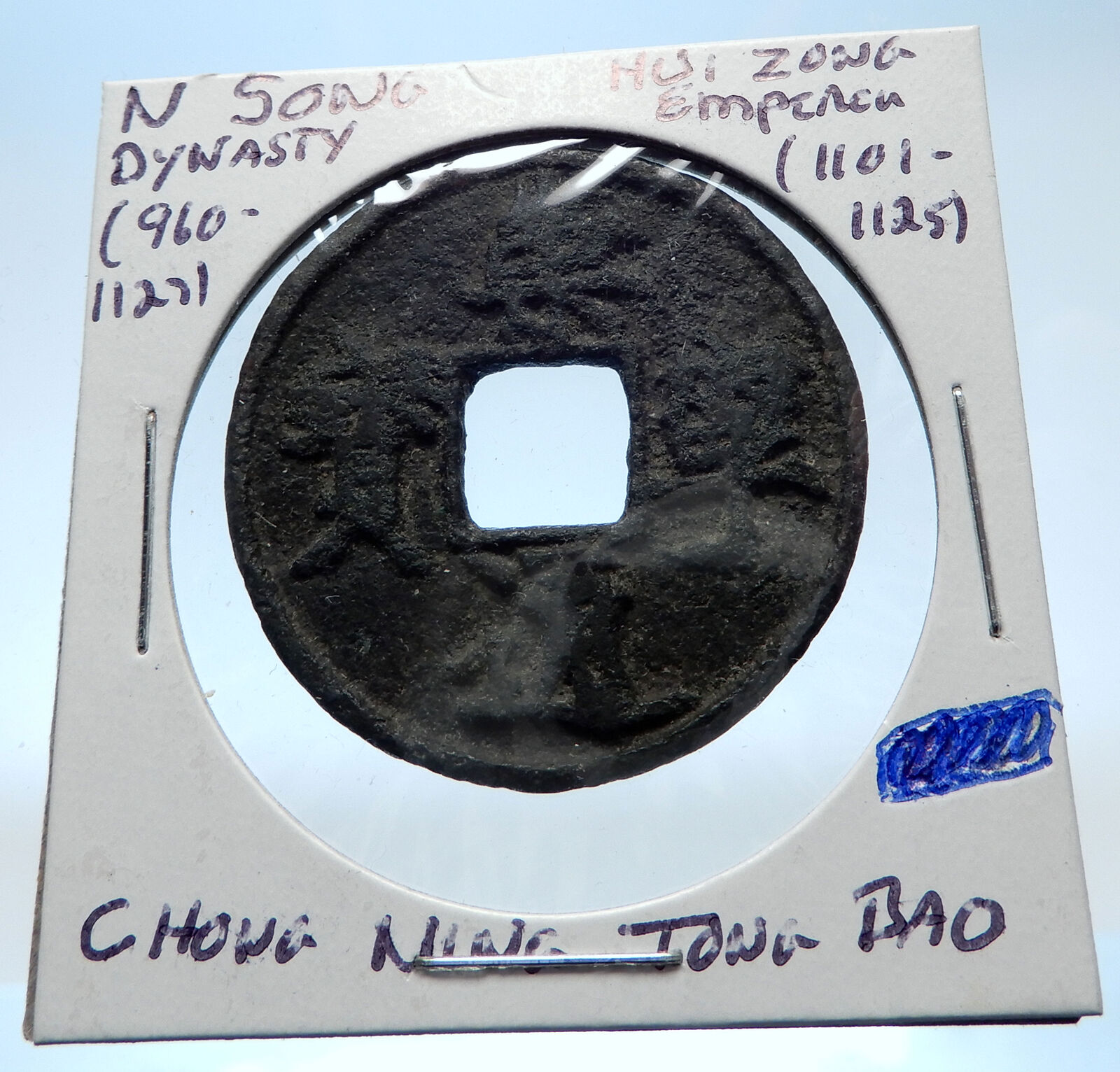

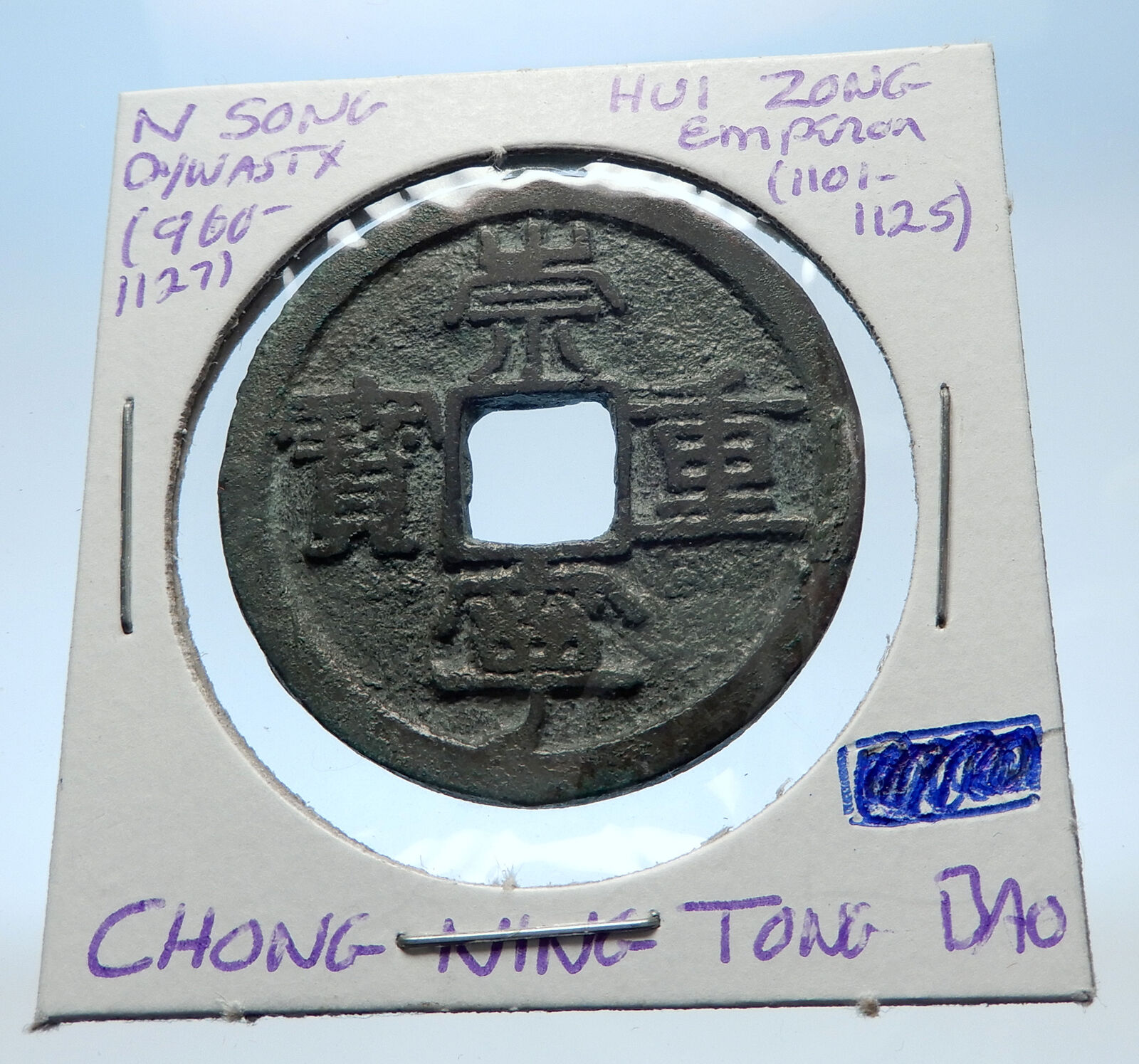

China – Ten Kingdoms – Southern Han – Chu Area (900-971 AD)

Lead Kai Yuan Tong

Bao Cash Token

19mm, Struck 900-971 AD

Reference: H# 15.231

Chinese Symbols.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Southern Han (Chinese: 南漢; pinyin: Nán Hàn; 917–971), officially Han (Chinese: 漢), originally Yue (Chinese: 越), was one of the ten kingdoms that existed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. It was located on China’s southern coast, controlling modern Guangdong and Guangxi. The kingdom greatly expanded its capital Xingwang Fu (Chinese: 興王府; pinyin: Xìngwáng Fǔ, present-day Guangzhou). It attempted but failed to annex the independent polity of Jinghai which was controlled by the Vietnamese. Southern Han (Chinese: 南漢; pinyin: Nán Hàn; 917–971), officially Han (Chinese: 漢), originally Yue (Chinese: 越), was one of the ten kingdoms that existed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. It was located on China’s southern coast, controlling modern Guangdong and Guangxi. The kingdom greatly expanded its capital Xingwang Fu (Chinese: 興王府; pinyin: Xìngwáng Fǔ, present-day Guangzhou). It attempted but failed to annex the independent polity of Jinghai which was controlled by the Vietnamese.

Liu Yin was named regional governor and military officer by the Tang court in 905. Though the Tang fell two years later, Liu did not declare himself the founder of a new kingdom as other southern leaders had done. He merely inherited the title of Prince of Nanping in 909.

It was not until Liu Yin’s death in 917 that his brother, Liu Yan, declared the founding of a new kingdom, which he initially called “Yue” (越); he changed the name to Han (漢) in 918. This was because his surname Liu (劉) was the imperial surname of the Han dynasty and he claimed to be a descendant of that famous dynasty. The kingdom is often referred to as the Southern Han Dynasty throughout China’s history. It attempted but failed to annex the independent polity of Jinghai which was controlled by the Vietnamese.

With its capital at present-day Guangzhou, the domains of the kingdom spread along the coastal regions of present-day Guangdong, Guangxi and the island of Hainan. It had borders with the kingdoms of Min, Chu and the Southern Tang as well as the non-Chinese kingdoms of Dali. The Southern Tang occupied all of the northern boundary of the Southern Han after Min and Chu were conquered by the Southern Tang in 945 and 951 respectively.

During the late 9th century as the Tang dynasty weakened, local Vietnamese lords began taking control of its domain in Jinghai (northern Vietnam). Southern Han campaigned twice against the Vietnamese in 931 and 938 in an attempt to add these Vietnamese territories to their realm, but failed both. During the late 9th century as the Tang dynasty weakened, local Vietnamese lords began taking control of its domain in Jinghai (northern Vietnam). Southern Han campaigned twice against the Vietnamese in 931 and 938 in an attempt to add these Vietnamese territories to their realm, but failed both.

The Five Dynasties ended in 960 when the Song Dynasty was founded to replace the Later Zhou. From that point, the new Song rulers set themselves about to continue the reunification process set in motion by the Later Zhou. Through the 960s and 970s, the Song increased its influence in the south until finally it was able to force the Southern Han dynasty to submit to its rule in 971.

Ten Kingdoms: Unlike the dynasties of northern China, which succeeded one another in rapid succession, the regimes of South China were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area. These were known as “The Ten Kingdoms” (in fact, some claimed the title of Emperor, such as Former Shu and Later Shu). Each court was a center of artistic excellence. The period is noted for the vitality of its poetry and for its economic prosperity. Commerce grew so quickly that there was a shortage of metallic currency. This was partly addressed by the creation of bank drafts, or “flying money” (feiqian), as well as by certificates of deposit. Wood block printing became common during this period, 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg’s press. Ten Kingdoms: Unlike the dynasties of northern China, which succeeded one another in rapid succession, the regimes of South China were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area. These were known as “The Ten Kingdoms” (in fact, some claimed the title of Emperor, such as Former Shu and Later Shu). Each court was a center of artistic excellence. The period is noted for the vitality of its poetry and for its economic prosperity. Commerce grew so quickly that there was a shortage of metallic currency. This was partly addressed by the creation of bank drafts, or “flying money” (feiqian), as well as by certificates of deposit. Wood block printing became common during this period, 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg’s press.

The Ten Kingdoms were:

- Yang Wu (907–937)

- Wuyue (907–978)

- Min (909–945)

- Ma Chu (907–951)

- Southern Han (917–971)

- Former Shu (907–925)

- Later Shu (934–965)

- Jingnan (924–963)

- Southern Tang (937–976)

- Northern Han (951–979)

Only ten are traditionally listed, hence the era’s name. Some historians, such as Bo Yang, count eleven, including Yan and Qi but not the Northern Han, viewing it as simply a continuation of Later Han. This era also coincided with the founding of the Liao dynasty in the north, and the Dali Kingdom in the southwest.

Other regimes during this period include Zhao, Yiwu Jiedushi, Dingnan Jiedushi, Wuping Jiedushi, Qingyuan Jiedushi, Yin, Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom, Guiyi Circuit, and Xiliangfu.

Cash was a type of coin of China and East Asia, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD. Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China as well as under Mongol, and Manchu rule. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast but, during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century.

In the modern era, these coins are considered to be Chinese “good luck coins”; they are hung on strings and round the necks of children, or over the beds of sick people. They hold a place in various superstitions, as well as Traditional Chinese medicine, and Feng shui. Currencies based on the Chinese cash coins include the Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn.

|

Southern Han (Chinese: 南漢; pinyin: Nán Hàn; 917–971), officially Han (Chinese: 漢), originally Yue (Chinese: 越), was one of the ten kingdoms that existed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. It was located on China’s southern coast, controlling modern Guangdong and Guangxi. The kingdom greatly expanded its capital Xingwang Fu (Chinese: 興王府; pinyin: Xìngwáng Fǔ, present-day Guangzhou). It attempted but failed to annex the independent polity of Jinghai which was controlled by the Vietnamese.

Southern Han (Chinese: 南漢; pinyin: Nán Hàn; 917–971), officially Han (Chinese: 漢), originally Yue (Chinese: 越), was one of the ten kingdoms that existed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. It was located on China’s southern coast, controlling modern Guangdong and Guangxi. The kingdom greatly expanded its capital Xingwang Fu (Chinese: 興王府; pinyin: Xìngwáng Fǔ, present-day Guangzhou). It attempted but failed to annex the independent polity of Jinghai which was controlled by the Vietnamese. During the late 9th century as the Tang dynasty weakened, local Vietnamese lords began taking control of its domain in Jinghai (northern Vietnam). Southern Han campaigned twice against the Vietnamese in 931 and 938 in an attempt to add these Vietnamese territories to their realm, but failed both.

During the late 9th century as the Tang dynasty weakened, local Vietnamese lords began taking control of its domain in Jinghai (northern Vietnam). Southern Han campaigned twice against the Vietnamese in 931 and 938 in an attempt to add these Vietnamese territories to their realm, but failed both. Ten Kingdoms: Unlike the dynasties of northern China, which succeeded one another in rapid succession, the regimes of South China were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area. These were known as “The Ten Kingdoms” (in fact, some claimed the title of Emperor, such as Former Shu and Later Shu). Each court was a center of artistic excellence. The period is noted for the vitality of its poetry and for its economic prosperity. Commerce grew so quickly that there was a shortage of metallic currency. This was partly addressed by the creation of bank drafts, or “flying money” (feiqian), as well as by certificates of deposit. Wood block printing became common during this period, 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg’s press.

Ten Kingdoms: Unlike the dynasties of northern China, which succeeded one another in rapid succession, the regimes of South China were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area. These were known as “The Ten Kingdoms” (in fact, some claimed the title of Emperor, such as Former Shu and Later Shu). Each court was a center of artistic excellence. The period is noted for the vitality of its poetry and for its economic prosperity. Commerce grew so quickly that there was a shortage of metallic currency. This was partly addressed by the creation of bank drafts, or “flying money” (feiqian), as well as by certificates of deposit. Wood block printing became common during this period, 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg’s press.