|

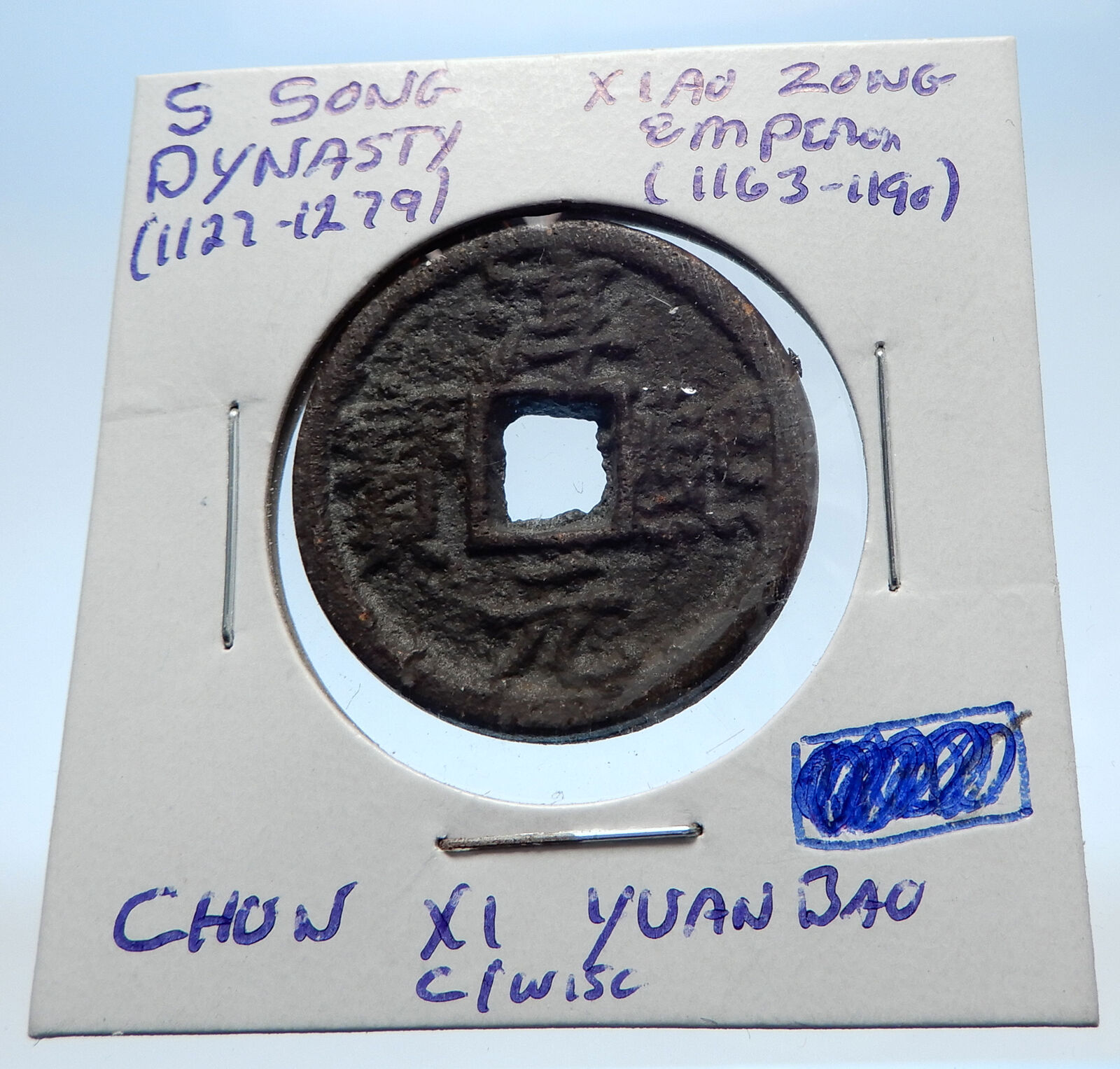

China –

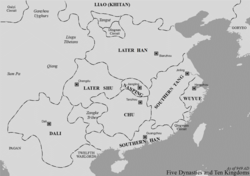

Five Dynasties – Later Han Dynasty (948-951 AD)

Emperor Gao Zu (947-948 AD)

Bronze Han Yuan Tong Bao Cash Token 22mm, Struck 947-948 AD

Reference: H# 15.7

Chinese Symbols.

Crescent below.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Liu Zhiyuan (Chinese: 劉知遠) (March 4, 895 – March 10, 948), later changed to Liu Gao (劉暠), formally Emperor Gaozu of (Later) Han ((後)漢高祖), was the ethnically-Shatuo founder of the Later Han, the fourth of the Five Dynasties in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of Chinese history. The subsequent Northern Han is not considered part of its history. Liu Zhiyuan (Chinese: 劉知遠) (March 4, 895 – March 10, 948), later changed to Liu Gao (劉暠), formally Emperor Gaozu of (Later) Han ((後)漢高祖), was the ethnically-Shatuo founder of the Later Han, the fourth of the Five Dynasties in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of Chinese history. The subsequent Northern Han is not considered part of its history.

Upon hearing the news that Liu Zhiyuan had declared himself emperor, Liao’s Emperor Taizong initially stationed several generals to prepare to impede him. However, the nearby circuits soon began to declare loyalty to Liu. Finding the Han Chinese to be turning against him, Emperor Taizong decided to return to Liao proper, although he left his cousin (his mother Empress Dowager Shulü’s nephew) Xiao Han in command at Kaifeng as Xuanwu Circuit’s military governor. He fell ill on the way back to Liao proper, and died near Heng Prefecture (恆州, Shunguo’s capital). His nephew Yelü Ruan the Prince of Yongkang, after a power struggle with the Han Chinese general Zhao Yanshou, claimed the Liao throne (as Emperor Shizong).

Meanwhile, Liu created his wife Empress Li empress. Hearing of Emperor Taizong’s departure from Kaifeng, he decided to march toward it, with Shi Hongzhao serving as his forward commander. He marched toward the Luoyang-Kaifeng region. Xiao became fearful and decided that he should withdraw from the region as well, but also believed that if there were no one in command at Kaifeng, the region would fall into turmoil and it would be impossible for him to withdraw. He therefore seized Li Siyuan’s youngest son Li Congyi and declared Li Congyi emperor, before departing Kaifeng. Li Congyi’s mother Consort Dowager Wang, however, finding the situation hopeless, had Li Congyi demote his own title to Prince of Liang after Xiao left, and submitted a petition welcoming Liu to Kaifeng. Liu subsequently arrived at Luoyang, and sent the general Guo Congyi (郭從義) to Kaifeng to kill Li Congyi and Consort Dowager Wang, before he headed to Kaifeng himself.

Reign at Kaifeng

Once at Kaifeng, Liu Zhiyuan declared it the eastern capital and Luoyang the western capital. He also declared the name of his state to be Han, but (for the time being) continued to use the era name of Tianfu, stating, “I do not yet have the heart to forget Jin.” Meanwhile, the military governors of various circuits continued to submit to him. That included Du Chongwei, who was then the military governor of Tianxiong, but Du was apprehensive because of his prior submission to Liao. When Liu then issued an edict moving him to Guide Circuit and moving Guide’s military governor Gao Xingzhou to Tianxiong, Du rebelled and sought aid from the Liao general Yelü Mada (耶律麻荅), who had been left in control of Heng by Emperor Shizong. Liu declared a campaign against Du and commissioned Gao as the commander of the army against Du, with Murong Yanchao serving as Gao’s deputy. Shortly after, the Han soldiers at Heng rose against Yelü Mada, and he was forced to flee himself, leaving Du supportless.

However, Du continued to hold Yedu’s defenses, aided by the Liao general Zhang Lian (張璉), who commanded Han Chinese soldiers from You Prefecture and who was particularly against Liu, because Liu had, upon entering Kaifeng, slaughtered the You Prefecture soldiers stationed there. Gao decided to try to surround the city for a long time to force its surrender, rather than force a costly battle. When Liu decided to go to the front himself to oversee the situation (as Du had previously claimed that if Liu came, he would surrender), Du continued to hold the defenses, and an attack advocated by Murong was unsuccessful, so Gao continued his strategy of surrounding the city. By the end of the year, the city was starving, and Du surrendered. Liu, against his own promise that Zhang would be spared, executed Zhang and his officers, although the soldiers were allowed to leave for You. Du was spared, but his assets were confiscated and awarded to the Later Han soldiers. This episode brought a strong criticism from the Song historian Sima Guang, the lead editor of the Zizhi Tongjian:

Han’s Emperor Gaozu killed 1,500 innocent soldiers from You; this showed a lack of compassion. He enticed Zhang Lian and then executed Zhang; this showed a lack of faith. He pardoned Du Chongwei despite Du’s great crimes; this showed a lack of proper punishment. Compassion is used to unite the people; faith is used to properly command others; and punishment is used to punish the wicked. If one did not have these three things, how does one protect a state? It is appropriate that the life of his state was not long.

Meanwhile, on Later Han’s western border, there was the issue that Zhao Yanshou’s son Zhao Kuangzan (趙匡贊) the military governor of Jinchang Circuit (晉昌, headquartered in modern Xi’an, Shaanxi) and Hou Yi (侯益) the military governor of Fengxiang, both having apprehensions about how they might be received by the Later Han emperor, submitted to Later Shu. In spring 948, Liu sent the imperial guard general Wang Jingchong west to attack Zhao and Hou. As Zhao was preparing to leave his own circuit and head to Later Shi’s capital Chengdu, Zhao’s staff member Li Su (李恕), however, persuaded Zhao that he should submit to Later Han, pointing out that Later Shu was a smaller state. Zhao therefore sent Li to Kaifeng to pay homage to Liu and to explain his prior actions. After receiving assurances from Liu that he would be accepted, Zhao offered to submit. Hou also changed his mind and resubmitted to Later Han. Liu decided to nevertheless send Wang to the west, under the excuse that the Ganzhou Huigu’s emissaries were being intercepted by the Dangxiang (i.e., Dingnan Circuit) and needed escort. He gave Wang secret instructions, “The hearts of Zhao Kuangzan and Hou Yi still cannot be known. When you get there, if they have already departed to come pay homage to me, then do not act further. If they were delaying and observing developments, act as you see fit.” When Wang reached the Jinchang capital Chang’an, Zhao had already departed, so Wang took his soldiers as well while trying to decide what to do with Hou, who resisted Later Shu but was also not immediately departing for Kaifeng.

While Liu Zhiyuan was on the campaign against Du, his oldest son Liu Chengxun (劉承訓), who was said to be kind, faithful, gentle, and capable, died. It was said that the people were saddened by Liu Chengxun’s passing. Liu Zhiyuan himself was greatly saddened, and it caused him to begin to be ill. By spring 948, he was extremely ill. He entrusted his younger son Liu Chengyou to Su Fengji, Yang Bin, Shi Hongzhao, and Guo Wei, stating, “My remaining breaths are getting short, and I cannot speak much. Chengyou is young and weak, so what happens after my death has to be entrusted to you.” He also told them to guard against Du Chongwei. After Liu Zhiyuan died the same day, these officials, without announcing his death, had Du and his sons put to death. Liu Chengyou was created the Prince of Zhou, and shortly after, when Liu Zhiyuan’s death was announced, Liu Chengyou succeeded him as emperor.

The Later Han (simplified Chinese: 后汉; traditional Chinese: 後漢; pinyin: Hòu Hàn) was founded in 947. It was the fourth of the Five Dynasties in imperial Chinese history, and the third consecutive Shatuo-led Chinese dynasty, however, other sources indicate that the Later Han emperors claimed patrilineal Han ancestry. It was among the shortest-lived of all Chinese regimes, lasting for slightly under four years before it was overcome by a rebellion that resulted in the founding of the Later Zhou. The Later Han (simplified Chinese: 后汉; traditional Chinese: 後漢; pinyin: Hòu Hàn) was founded in 947. It was the fourth of the Five Dynasties in imperial Chinese history, and the third consecutive Shatuo-led Chinese dynasty, however, other sources indicate that the Later Han emperors claimed patrilineal Han ancestry. It was among the shortest-lived of all Chinese regimes, lasting for slightly under four years before it was overcome by a rebellion that resulted in the founding of the Later Zhou.

Liu Zhiyuan was military governor of Bingzhou, an area around Taiyuan in present-day Shanxi that had long been a stronghold of the sinicized Shatuo. However, the Later Jin he served was weak and little more than a puppet of the expanding Khitan empire to the north. When the Later Jin finally did decide to defy them, the Khitan sent an expedition south that resulted in the destruction of the Later Jin.

The Khitan force made it all the way to the Yellow River before the emperor decided to return to his base in present-day Beijing, in the heart of the contentious Sixteen Prefectures. However, following constant harassment from the Chinese on the return route, he died of an illness in May 947. The combination of the fall of the Later Jin and the succession crisis among the Khitan resulted in a power vacuum. Liu Zhiyuan was able to fill that void and founded the Later Han.

Sources conflict as to the origin of the Later Han and Northern Han Emperors, some indicate Shatuo ancestry while another claims that the Emperors claimed patrilineal Han Chinese ancestry.

The Later Han was among the shortest-lived regimes in the long history of China. Liu Zhiyuan died the year following the founding of the dynasty, to be succeeded by his teenaged son. The dynasty was overthrown two years later when a Han Chinese named Guo Wei led a military coup and declared himself emperor of the Later Zhou.

Cash was a type of coin of China and East Asia, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD. Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China as well as under Mongol, and Manchu rule. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast but, during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century.

In the modern era, these coins are considered to be Chinese “good luck coins”; they are hung on strings and round the necks of children, or over the beds of sick people. They hold a place in various superstitions, as well as Traditional Chinese medicine, and Feng shui. Currencies based on the Chinese cash coins include the Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn.

|

Liu Zhiyuan (Chinese: 劉知遠) (March 4, 895 – March 10, 948), later changed to Liu Gao (劉暠), formally Emperor Gaozu of (Later) Han ((後)漢高祖), was the ethnically-Shatuo founder of the Later Han, the fourth of the Five Dynasties in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of Chinese history. The subsequent Northern Han is not considered part of its history.

Liu Zhiyuan (Chinese: 劉知遠) (March 4, 895 – March 10, 948), later changed to Liu Gao (劉暠), formally Emperor Gaozu of (Later) Han ((後)漢高祖), was the ethnically-Shatuo founder of the Later Han, the fourth of the Five Dynasties in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of Chinese history. The subsequent Northern Han is not considered part of its history. The Later Han (simplified Chinese: 后汉; traditional Chinese: 後漢; pinyin: Hòu Hàn) was founded in 947. It was the fourth of the Five Dynasties in imperial Chinese history, and the third consecutive Shatuo-led Chinese dynasty, however, other sources indicate that the Later Han emperors claimed patrilineal Han ancestry. It was among the shortest-lived of all Chinese regimes, lasting for slightly under four years before it was overcome by a rebellion that resulted in the founding of the Later Zhou.

The Later Han (simplified Chinese: 后汉; traditional Chinese: 後漢; pinyin: Hòu Hàn) was founded in 947. It was the fourth of the Five Dynasties in imperial Chinese history, and the third consecutive Shatuo-led Chinese dynasty, however, other sources indicate that the Later Han emperors claimed patrilineal Han ancestry. It was among the shortest-lived of all Chinese regimes, lasting for slightly under four years before it was overcome by a rebellion that resulted in the founding of the Later Zhou.