|

Alexander III the Great – King of Macedonia 336-323 B.C.

Bronze 16mm (4.22 grams) Pella or Amphipolis: 334 B.C. LIFETIME ISSUE!

Reference: SNGCop 1120; Liampi M7

Macedonian shield; around, five double crescents with five pellets between each;

in centre, thunderbolt.

B – A on either side of Crested Macedonian helmet.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Alexander III of Macedon (20/21 July 356 – 10/11 June 323 BC),

commonly known as Alexander the Great from the Greek alexo “to

defend, help” + aner “man”), was a king of

Macedon

, a state in northern

ancient Greece

. Born in

Pella

in 356 BC, Alexander was tutored by

Aristotle

until the age of 16. By the age of

thirty, he had created one of the

largest empires

of the

ancient world

, stretching from the

Ionian Sea

to the

Himalayas

.He was undefeated in battle and is

considered one of history’s most successful commanders.

Alexander

succeeded his father,

Philip II of Macedon

, to the throne in 336 BC

after Philip was assassinated. Upon Philip’s death, Alexander inherited a strong

kingdom and an experienced army. He was awarded the generalship of Greece and

used this authority to launch his father’s military expansion plans. In 334 BC,

he invaded

Persian

-ruled

Asia Minor

and began a

series of campaigns

that lasted ten years.

Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most

notably the battles of

Issus

and

Gaugamela

. He subsequently overthrew the

Persian King

Darius III

and conquered the entirety of the

Persian Empire

. At that point, his empire

stretched from the

Adriatic Sea

to the

Indus River

.

Seeking to reach the “ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea”, he

invaded India

in 326 BC, but was eventually

forced to turn back at the demand of his troops. Alexander died in

Babylon

in 323 BC, without executing a series

of planned campaigns that would have begun with an invasion of

Arabia

. In the years following his death, a

series of civil wars tore his empire apart, resulting in several states ruled by

the Diadochi

, Alexander’s surviving generals and

heirs.

Alexander’s legacy includes the

cultural diffusion

his conquests engendered. He

founded some

twenty cities that bore his name

, most notably

Alexandria

in Egypt. Alexander’s settlement of

Greek colonists and the resulting spread of Greek culture in the east resulted

in a new

Hellenistic civilization

, aspects of which were

still evident in the traditions of the

Byzantine Empire

in the mid-15th century.

Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mold of

Achilles

, and he features prominently in the

history and myth of Greek and non-Greek cultures. He became the measure against

which military leaders compared themselves, and

military academies

throughout the world still

teach his tactics.

Early life

Lineage and childhood

Alexander was born on the 6th day of the ancient Greek month of

Hekatombaion

, in

Pella

, the capital of the

Ancient Greek

Kingdom of Macedon

.He was the son of the king

of Macedon,

Philip II

, and his fourth wife,

Olympias

, the daughter of

Neoptolemus I

, king of

Epirus

. Although Philip had seven or eight

wives, Olympias was his principal wife for some time, likely a result of giving

birth to Alexander.

Philip II

of Macedon

, Alexander’s father.

On the day that Alexander was born, Philip was preparing a

siege

on the city of

Potidea

on the peninsula of

Chalcidice

. That same day, Philip received news

that his general

Parmenion

had defeated the combined

Illyrian

and

Paeonian

armies, and that his horses had won at

the

Olympic Games

. It was also said that on this

day, the

Temple of Artemis

in

Ephesus

, one of the

Seven Wonders of the World

, burnt down. This

led

Hegesias of Magnesia

to say that it had burnt

down because Artemis

was away, attending the birth of

Alexander.

Bust of a young Alexander the Great from the Hellenistic era,

British

Museum

In his early years, Alexander was raised by a nurse,

Lanike

, sister of Alexander’s future general

Cleitus the Black

. Later in his childhood,

Alexander was tutored by the strict

Leonidas

, a relative of his mother, and by

Philip’s general

Lysimachus

. Alexander was raised in the manner

of noble Macedonian youths, learning to read, play the

lyre, ride, fight, and hunt.

When Alexander was ten years old, a trader from

Thessaly

brought Philip a horse, which he

offered to sell for thirteen

talents

. The horse refused to be mounted and

Philip ordered it away. Alexander however, detecting the horse’s fear of its own

shadow, asked to tame the horse, which he eventually managed. Philip, overjoyed

at this display of courage and ambition, kissed his son tearfully, declaring:

“My boy, you must find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedon is too

small for you”, and bought the horse for him.Alexander named it

Bucephalas

, meaning “ox-head”. Bucephalas

carried Alexander as far as

Pakistan

. When the animal died at age thirty,

Alexander named a city after him,

Bucephala

.

When Alexander was 13, Philip began to search for a

tutor

, chose

Aristotle

and provided the Temple of the Nymphs

at Mieza

as a classroom. In return for teaching

Alexander, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle’s hometown of

Stageira

, which Philip had razed, and to

repopulate it by buying and freeing the ex-citizens who were slaves, or

pardoning those who were in exile.

Mieza was like a boarding school for Alexander and the children of Macedonian

nobles, such as

Ptolemy

,

Hephaistion

, and

Cassander

. Many of these students would become

his friends and future generals, and are often known as the ‘Companions’.

Aristotle taught Alexander and his companions about medicine, philosophy,

morals, religion, logic, and art. Under Aristotle’s tutelage, Alexander

developed a passion for the works of

Homer

, and in particular the

Iliad

; Aristotle gave him an annotated

copy, which Alexander later carried on his campaigns.

At age 16, Alexander’s education under Aristotle ended. Philip waged war

against Byzantion

, leaving Alexander in charge as

regent

and

heir apparent

. During Philip’s absence, the

Thracian

Maedi

revolted against Macedonia. Alexander

responded quickly, driving them from their territory. He colonized it with

Greeks, and founded a city named

Alexandropolis

.

Upon Philip’s return, he dispatched Alexander with a small force to subdue

revolts in southern Thrace

. Campaigning against the Greek city of

Perinthus

, Alexander is reported to have saved

his father’s life. Meanwhile, the city of

Amphissa

began to work lands that were sacred

to Apollo

near

Delphi

, a sacrilege that gave Philip the

opportunity to further intervene in Greek affairs. Still occupied in Thrace, he

ordered Alexander to muster an army for a campaign in Greece. Concerned that

other Greek states might intervene, Alexander made it look as though he was

preparing to attack Illyria instead. During this turmoil, the Illyrians invaded

Macedonia, only to be repelled by Alexander.

Philip and his army joined his son in 338 BC, and they marched south through

Thermopylae

, taking it after stubborn

resistance from its Theban garrison. They went on to occupy the city of

Elatea

, only a few days’ march from both Athens

and Thebes. The Athenians, led by

Demosthenes

, voted to seek alliance with Thebes

against Macedonia. Both Athens and Philip sent embassies to win Thebes’ favor,

but Athens won the contest.Philip marched on Amphissa (ostensibly acting on the

request of the

Amphictyonic League

), capturing the mercenaries

sent there by

Demosthenes

and accepting the city’s surrender.

Philip then returned to Elatea, sending a final offer of peace to Athens and

Thebes, who both rejected it.

As Philip marched south, his opponents blocked him near

Chaeronea

,

Boeotia

. During the ensuing

Battle of Chaeronea

, Philip commanded the right

wing and Alexander the left, accompanied by a group of Philip’s trusted

generals. According to the ancient sources, the two sides fought bitterly for

some time. Philip deliberately commanded his troops to retreat, counting on the

untested Athenian

hoplites

to follow, thus breaking their line.

Alexander was the first to break the Theban lines, followed by Philip’s

generals. Having damaged the enemy’s cohesion, Philip ordered his troops to

press forward and quickly routed them. With the Athenians lost, the Thebans were

surrounded. Left to fight alone, they were defeated.

After the victory at Chaeronea, Philip and Alexander marched unopposed into

the Peloponnese, welcomed by all cities; however, when they reached

Sparta

, they were refused, but did not resort

to war.At

Corinth

, Philip established a “Hellenic

Alliance” (modeled on the old

anti-Persian alliance

of the

Greco-Persian Wars

), which included most Greek

city-states except Sparta. Philip was then named

Hegemon

(often translated as “Supreme

Commander”) of this league (known by modern scholars as the

League of Corinth

), and announced his plans to

attack the

Persian Empire

.

When Philip returned to Pella, he fell in love with and married

Cleopatra Eurydice

, the niece of his general

Attalus

. The marriage made Alexander’s position

as heir less secure, since any son of Cleopatra Eurydice would be a fully

Macedonian heir, while Alexander was only half-Macedonian.

Alexander fled Macedon with his mother, dropping her off with her brother,

King

Alexander I of Epirus

in

Dodona

, capital of the

Molossians

.He continued to Illyria, where he

sought refuge with the Illyrian King and was treated as a guest, despite having

defeated them in battle a few years before. However, it appears Philip never

intended to disown his politically and militarily trained son. Accordingly,

Alexander returned to Macedon after six months due to the efforts of a family

friend,

Demaratus

, who mediated between the two

parties.

In 336 BC, while at

Aegae

attending the wedding of his daughter

Cleopatra

to Olympias’s brother,

Alexander I of Epirus

, Philip was assassinated

by the captain of his

bodyguards

,

Pausanias

. As Pausanias tried to escape, he

tripped over a vine and was killed by his pursuers, including two of Alexander’s

companions, Perdiccas

and

Leonnatus

. Alexander was proclaimed king by the

nobles and

army

at the age of 20.

Alexander began his reign by eliminating potential rivals to the throne. He

had his cousin, the former

Amyntas IV

, executed. He also had two

Macedonian princes from the region of

Lyncestis

killed, but spared a third,

Alexander Lyncestes

. Olympias had Cleopatra

Eurydice and Europa, her daughter by Philip, burned alive. When Alexander

learned about this, he was furious. Alexander also ordered the murder of

Attalus, who was in command of the advance guard of the army in Asia Minor and

Cleopatra’s uncle.

News of Philip’s death roused many states into revolt, including Thebes,

Athens, Thessaly, and the Thracian tribes north of Macedon. When news of the

revolts reached Alexander, he responded quickly. Though advised to use

diplomacy, Alexander mustered the Macedonian cavalry of 3,000 and rode south

towards Thessaly. He found the Thessalian army occupying the pass between

Mount Olympus

and

Mount Ossa

, and ordered his men to ride over

Mount Ossa. When the Thessalians awoke the next day, they found Alexander in

their rear and promptly surrendered, adding their cavalry to Alexander’s force.

He then continued south towards the

Peloponnese

.

Alexander stopped at Thermopylae, where he was recognized as the leader of

the Amphictyonic League before heading south to

Corinth

. Athens sued for peace and Alexander

pardoned the rebels. The famous

encounter between Alexander and Diogenes the Cynic

occurred during Alexander’s stay in Corinth. When Alexander asked Diogenes what

he could do for him, the philosopher disdainfully asked Alexander to stand a

little to the side, as he was blocking the sunlight. This reply apparently

delighted Alexander, who is reported to have said “But verily, if I were not

Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes.” At Corinth Alexander took the title of

Hegemon (“leader”), and like Philip, was appointed commander for the

coming war against Persia. He also received news of a Thracian uprising.

Alexander’s army crossed the

Hellespont

in 334 BC with approximately 48,100

soldiers, 6,100 cavalry and a fleet of 120 ships with crews numbering

38,000,drawn from Macedon and various Greek city-states, mercenaries, and

feudally raised soldiers from

Thrace

,

Paionia

, and

Illyria

. He showed his intent to conquer the

entirety of the Persian Empire by throwing a spear into Asian soil and saying he

accepted Asia as a gift from the gods. This also showed Alexander’s eagerness to

fight, in contrast to his father’s preference for diplomacy.

After an initial victory against Persian forces at the

Battle of the Granicus

, Alexander accepted the

surrender of the Persian provincial capital and treasury of

Sardis

; he then proceeded along the

Ionian

coast. Though Alexander believed in his

divine right to expend the lives of men in battle, he did experience sorrow, as

those who died were rewarded generously. He did not directly influence the

culture of the Persians they did not feel the need to begin a rebellion as their

men and rulers were treated with proper respect.

The Levant and Syria

Alexander journeyed south but was met by Darius’ significantly larger army

which he easily defeated, causing Darius to panic. Although he was chased by

some troops ‘Alexander treated them (his family) with the respect out of

consideration’ which demonstrated his continued generosity and kindness towards

those he conquered.Darius fled the battle, causing his army to collapse, and

left behind his wife, his two daughters, his mother

Sisygambis

, and a fabulous treasure.He offered

a peace treaty

that included the lands he had

already lost, and a ransom of 10,000

talents

for his family. Alexander replied that

since he was now king of Asia, it was he alone who decided territorial

divisions.

Alexander proceeded to take possession of

Syria

, and most of the coast of the

Levant

. In the following year, 332 BC, he was

forced to attack

Tyre

, which he captured after a long and

difficult

siege

.Alexander massacred the men of military

age and sold the women and children into

slavery

.

Egypt

When Alexander destroyed Tyre, most of the towns on the route to Egypt

quickly capitulated, with the exception of

Gaza. The stronghold at Gaza was heavily fortified and built on a

hill, requiring a siege. Alexander came upon the city only to be met with a

surprising resistance and fortification. When ‘his engineers pointed out to him

that because of the height of the mound it would be impossible… this encouraged

Alexander all the more to make the attempt’ . The divine right that Alexander

believed he had gave him confidence of a miracle occurring. After three

unsuccessful assaults, the stronghold fell, but not before Alexander had

received a serious shoulder wound. As in Tyre, men of military age were put to

the sword and the women and children sold into slavery.

Jerusalem instead opened its gates in surrender, and according to

Josephus

, Alexander was shown the

Book of Daniel

‘s prophecy, presumably chapter

8, which described a mighty Greek king who would conquer the Persian Empire. He

spared Jerusalem and pushed south into Egypt.

Alexander advanced on Egypt in later 332 BC, where he was regarded as a

liberator. He was pronounced the new “master of the Universe” and son of the

deity of Amun

at the

Oracle

of

Siwa Oasis

in the

Libyan

desert.Henceforth, Alexander often

referred to

Zeus-Ammon

as his true father, and subsequent

currency depicted him adorned with rams horn as a symbol of his divinity. During

his stay in Egypt, he founded

Alexandria-by-Egypt

, which would become the

prosperous capital of the

Ptolemaic Kingdom

after his death.

Bust of

Alexander

the Great

as Helios (Musei

Capitolini)

Assyria and Babylonia

Leaving Egypt in 331 BC, Alexander marched eastward into

Mesopotamia

(now northern

Iraq) and again defeated Darius, at the

Battle of Gaugamela

. Darius once more fled the

field, and Alexander chased him as far as

Arbela

. Gaugamela would be the final and

decisive encounter between the two. Darius fled over the mountains to

Ecbatana

(modern

Hamedan

), while Alexander captured

Babylon

.

Persia

From Babylon, Alexander went to

Susa, one of the

Achaemenid

capitals, and captured its legendary

treasury. He sent the bulk of his army to the Persian ceremonial capital of

Persepolis

via the

Royal Road

. Alexander himself took selected

troops on the direct route to the city. He had to storm the pass of the

Persian Gates

(in the modern

Zagros Mountains

) which had been blocked by a

Persian army under

Ariobarzanes

and then hurried to Persepolis

before its garrison could loot the treasury.

Alexander fighting the Persian king

Darius III

.

From

Alexander Mosaic

,

Naples National

Archaeological Museum

On entering Persepolis, Alexander allowed his troops to loot the city for

several days.Alexander stayed in Persepolis for five months. During his stay a

fire broke out in the eastern palace of

Xerxes

and spread to the rest of the city.

Possible causes include a drunken accident or deliberate revenge for the burning

of the

Acropolis of Athens

during the

Second Persian War

.

Fall of the

Empire and the East

Alexander then chased Darius, first into Media, and then Parthia.The Persian

king no longer controlled his own destiny, and was taken prisoner by

Bessus

, his

Bactrian

satrap and kinsman.As Alexander

approached, Bessus had his men fatally stab the Great King and then declared

himself Darius’ successor as Artaxerxes V, before retreating into Central Asia

to launch a

guerrilla

campaign against Alexander. Alexander

buried Darius’ remains next to his Achaemenid predecessors in a regal funeral.He

claimed that, while dying, Darius had named him as his successor to the

Achaemenid throne. The Achaemenid Empire is normally considered to have fallen

with Darius.

Alexander viewed Bessus as a usurper and set out to defeat him.

This campaign, initially against Bessus, turned into a grand tour of central

Asia. Alexander founded a series of new cities, all called Alexandria, including

modern Kandahar

in Afghanistan, and

Alexandria Eschate

(“The Furthest”) in modern

Tajikistan

. The campaign took Alexander through

Media

,

Parthia

,

Aria

(West Afghanistan),

Drangiana

,

Arachosia

(South and Central Afghanistan),

Bactria

(North and Central Afghanistan), and

Scythia

.

Spitamenes

, who held an undefined position in

the satrapy of Sogdiana, in 329 BC betrayed Bessus to

Ptolemy

, one of Alexander’s trusted companions,

and Bessus was executed. However, when, at some point later, Alexander was on

the Jaxartes

dealing with an incursion by a horse

nomad army, Spitamenes raised Sogdiana in revolt. Alexander personally defeated

the Scythians at the

Battle of Jaxartes

and immediately launched a

campaign against Spitamenes, defeating him in the Battle of Gabai. After the

defeat, Spitamenes was killed by his own men, who then sued for peace.The empire

began falling as military leaders and eventually Alexander died.

Problems and plots

During this time, Alexander took the Persian title “King of Kings” (Shahanshah)

and adopted some elements of Persian dress and customs at his court, notably the

custom of

proskynesis

, either a symbolic kissing of

the hand, or prostration on the ground, that Persians showed to their social

superiors. The Greeks regarded the gesture as the province of

deities

and believed that Alexander meant to

deify himself by requiring it. This cost him the sympathies of many of his

countrymen, and he eventually abandoned it.

A plot against his life was revealed, and one of his officers,

Philotas

, was executed for failing to alert

Alexander. The death of the son necessitated the death of the father, and thus

Parmenion

, who had been charged with guarding

the treasury at Ecbatana

, was assassinated at Alexander’s

command, to prevent attempts at vengeance. Most infamously, Alexander personally

killed the man who had saved his life at Granicus,

Cleitus the Black

, during a violent drunken

altercation at

Maracanda

(modern day

Samarkand

in

Uzbekistan

), in which Cleitus accused Alexander

of several judgemental mistakes and most especially, of having forgot the

Macedonian ways in favour of a corrupt oriental lifestyle.

Macedon in

Alexander’s absence

When Alexander set out for Asia, he left his general

Antipater

, an experienced military and

political leader and part of Philip II’s “Old Guard”, in charge of Macedon.

Alexander’s sacking of Thebes ensured that Greece remained quiet during his

absence. The one exception was a call to arms by Spartan king

Agis III

in 331 BC, whom Antipater defeated and

killed in battle at

Megalopolis

the following year. Antipater

referred the Spartans’ punishment to the League of Corinth, which then deferred

to Alexander, who chose to pardon them. There was also considerable friction

between Antipater and Olympias, and each complained to Alexander about the

other.

In general, Greece enjoyed a period of peace and prosperity during

Alexander’s campaign in Asia. Alexander sent back vast sums from his conquest,

which stimulated the economy and increased trade across his empire.However,

Alexander’s constant demands for troops and the migration of Macedonians

throughout his empire depleted Macedon’s manpower, greatly weakening it in the

years after Alexander, and ultimately led to its subjugation by Rome.

Indian campaign

After the death of

Spitamenes

and his marriage to Roxana (Roshanak

in

Bactrian

) to cement relations with his new

satrapies, Alexander turned to the

Indian subcontinent

. He invited the

chieftains

of the former satrapy of

Gandhara

, in the north of what is now

Pakistan

, to come to him and submit to his

authority.

Omphis

, ruler of

Taxila

, whose kingdom extended from the

Indus

to the

Hydaspes

, complied, but the chieftains of some

hill clans, including the

Aspasioi

and

Assakenoi

sections of the

Kambojas

(known in Indian texts also as

Ashvayanas and Ashvakayanas), refused to submit.In the winter of 327/326 BC,

Alexander personally led a campaign against these clans; the Aspasioi of

Kunar

valleys

, the Guraeans of the

Guraeus

valley, and the Assakenoi of the

Swat

and

Buner

valleys.A fierce contest ensued with the

Aspasioi in which Alexander was wounded in the shoulder by a dart, but

eventually the Aspasioi lost. Alexander then faced the Assakenoi, who fought in

the strongholds of Massaga, Ora and

Aornos

.The fort of Massaga was reduced only

after days of bloody fighting, in which Alexander was wounded seriously in the

ankle.

After Aornos, Alexander crossed the Indus and fought and won an epic battle

against King Porus

, who ruled a region in the

Punjab

, in the

Battle of the Hydaspes

in 326 BC. Alexander was

impressed by Porus’s bravery, and made him an ally. He appointed Porus as

satrap, and added to Porus’ territory land that he did not previously own.

Choosing a local helped him control these lands so distant from Greece.Alexander

founded two cities on opposite sides of the

Hydaspes

river, naming one

Bucephala

, in honor of his horse, who died

around this time.The other was

Nicaea

(Victory) located at the site of modern

day Mong, Punjab

.

Revolt of the army

East of Porus’ kingdom, near the

Ganges River

, were the

Nanda Empire

of

Magadha

and further east the

Gangaridai Empire

of

Bengal

. Fearing the prospect of facing other

large armies and exhausted by years of campaigning, Alexander’s army mutinied at

the Hyphasis River

, refusing to march farther east.

This river thus marks the easternmost extent of Alexander’s conquests. Alexander

tried to persuade his soldiers to march farther, but his general

Coenus

pleaded with him to change his opinion

and return; the men, he said, “longed to again see their parents, their wives

and children, their homeland”. Alexander eventually agreed and turned south,

marching along the

Indus

. Along the way his army conquered the

Malli

clans (in modern day

Multan

) and other Indian tribes.

Alexander sent much of his army to

Carmania

(modern southern

Iran) with general

Craterus

, and commissioned a fleet to explore

the Persian Gulf

shore under his admiral

Nearchus

, while he led the rest back to Persia

through the more difficult southern route along the

Gedrosian Desert

and

Makran

(now part of southern Iran and

Pakistan).Alexander reached Susa in 324 BC, but not before losing many men to

the harsh desert.

Last years in Persia

Discovering that many of his

satraps

and military governors had misbehaved

in his absence, Alexander executed several of them as examples on his way to

Susa. As a gesture of thanks, he paid off the debts of his soldiers,

and announced that he would send over-aged and disabled veterans back to

Macedon, led by Craterus. His troops misunderstood his intention and mutinied at

the town of Opis

. They refused to be sent away and

criticized his adoption of Persian customs and dress and the introduction of

Persian officers and soldiers into Macedonian units.

Death and succession

On either 10 or 11 June 323 BC, Alexander died in the palace of

Nebuchadnezzar II

, in

Babylon

, at age 32. Details of the death differ

slightly – Plutarch

‘s account is that roughly 14 days

before his death, Alexander entertained admiral

Nearchus

, and spent the night and next day

drinking with

Medius of Larissa

.He developed a fever, which

worsened until he was unable to speak. Diodorus, Plutarch, Arrian and Justin

all mentioned the theory that Alexander was poisoned.

The strongest argument against the poison theory is the fact that twelve days

passed between the start of his illness and his death; such long-acting poisons

were probably not available. In 2010, however, a new theory proposed that the

circumstances of his death were compatible with poisoning by water of the river

Styx (Mavroneri)

that contained

calicheamicin

, a dangerous compound produced by

bacteria

.

Several

natural causes

(diseases) have been suggested,

including malaria

and

typhoid fever

.

After death

Alexander’s body was laid in a gold anthropoid

sarcophagus

that was filled with honey, which

was in turn placed in a gold casket. While Alexander’s funeral cortege was on

its way to Macedon, Ptolemy stole it and took it to Memphis. His successor,

Ptolemy II Philadelphus

, transferred the

sarcophagus to Alexandria, where it remained until at least

late Antiquity

.

Ptolemy IX Lathyros

, one of Ptolemy’s final

successors, replaced Alexander’s sarcophagus with a glass one so he could

convert the original to coinage.

Pompey

,

Julius Caesar

and

Augustus

all visited the tomb in Alexandria.

Caligula

was said to have taken Alexander’s

breastplate from the tomb for his own use. In c. AD 200, Emperor

Septimius Severus

closed Alexander’s tomb to

the public. His son and successor,

Caracalla

, a great admirer, visited the tomb

during his own reign. After this, details on the fate of the tomb are hazy.

Division of the empire

Alexander’s death was so sudden that when reports of his death reached

Greece, they were not immediately believed.Alexander had no obvious or

legitimate heir, his son Alexander IV by Roxane being born after Alexander’s

death.According to Diodorus, Alexander’s companions asked him on his deathbed to

whom he bequeathed his kingdom; his laconic reply was “tôi kratistôi”—”to the

strongest”.

In 321 BC, Macedonian unity collapsed, and 40 years of war between “The

Successors” (Diadochi) ensued before the Hellenistic world settled into

four stable power blocks: the

Ptolemaic Kingdom

of Egypt, the

Seleucid Empire

in the east, the Kingdom of

Pergamon

in Asia Minor, and Macedon. In the

process, both Alexander IV and Philip III were murdered.

Character

Alexander earned the epithet “the Great” due to his unparalleled success as a

military commander. He never lost a battle, despite typically being

outnumbered.This was due to use of terrain,

phalanx

and cavalry tactics, bold strategy, and

the fierce loyalty of his troops.The

Macedonian phalanx

, armed with the

sarissa

, a spear 6 metres (20 ft) long, had

been developed and perfected by Philip II through rigorous training, and

Alexander used its speed and maneuverability to great effect against larger but

more disparate Persian forces.Alexander also recognized the potential for

disunity among his diverse army, which employed various languages and weapons.

He overcame this by being personally involved in battle,in the manner of a

Macedonian king.

When faced with opponents who used unfamiliar fighting techniques, such as in

Central Asia and India, Alexander adapted his forces to his opponents’ style.

Thus, in Bactria

and

Sogdiana

, Alexander successfully used his

javelin throwers and archers to prevent outflanking movements, while massing his

cavalry at the center. In India, confronted by Porus’ elephant corps, the

Macedonians opened their ranks to envelop the elephants and used their sarissas

to strike upwards and dislodge the elephants’ handlers.

Physical appearance:

Greek historian Arrian

described Alexander as:

The strong, handsome commander with one eye dark as the night and one

blue as the sky.

Alexander suffered from

heterochromia iridum

: that one eye was dark and

the other light.

Personality

Some of Alexander’s strongest personality traits formed in response to his

parents.His mother had huge ambitions, and encouraged him to believe it was his

destiny to conquer the Persian Empire. Olympias’ influence instilled a sense of

destiny in him, and Plutarch tells us that his ambition “kept his spirit serious

and lofty in advance of his years”. However, his father Philip was Alexander’s

most immediate and influential role model, as the young Alexander watched him

campaign practically every year, winning victory after victory while ignoring

severe wounds.Alexander’s relationship with his father forged the competitive

side of his personality; he had a need to out-do his father, illustrated by his

reckless behavior in battle. While Alexander worried that his father would leave

him “no great or brilliant achievement to be displayed to the world”, he also

downplayed his father’s achievements to his companions.

According to Plutarch, among Alexander’s traits were a violent temper and

rash, impulsive nature, which undoubtedly contributed to some of his decisions.

Although Alexander was stubborn and did not respond well to orders from his

father, he was open to reasoned debate. He had a calmer side—perceptive,

logical, and calculating. He had a great desire for knowledge, a love for

philosophy, and was an avid reader.This was no doubt in part due to Aristotle’s

tutelage; Alexander was intelligent and quick to learn. His intelligent and

rational side was amply demonstrated by his ability and success as a general.

Alexander was erudite and patronized both arts and sciences.However, he had

little interest in sports or the

Olympic games

(unlike his father), seeking only

the

Homeric

ideals of honor (timê) and glory

(kudos). He had great

charisma

and force of personality,

characteristics which made him a great leader. His unique abilities were further

demonstrated by the inability of any of his generals to unite Macedonia and

retain the Empire after his death – only Alexander had the ability to do so.

During his final years, and especially after the death of Hephaestion,

Alexander began to exhibit signs of

megalomania

and

paranoia

.His extraordinary achievements,

coupled with his own ineffable sense of destiny and the flattery of his

companions, may have combined to produce this effect.

He appears to have believed himself a deity, or at least sought to deify

himself. Olympias always insisted to him that he was the son of Zeus,a theory

apparently confirmed to him by the oracle of Amun at

Siwa

. He began to identify himself as the son

of Zeus-Ammon.Alexander adopted elements of Persian dress and customs at court,

notably

proskynesis

, a practice that Macedonians

disapproved, and were loath to perform. This behavior cost him the sympathies of

many of his countrymen.However, Alexander also was a pragmatic ruler who

understood the difficulties of ruling culturally disparate peoples, many of whom

lived in kingdoms where the king was divine.Thus, rather than megalomania, his

behavior may simply have been a practical attempt at strengthening his rule and

keeping his empire together.

Personal relationships

Alexander, left, and

Hephaestion

, right

The central personal relationship of Alexander’s life was with his friend,

general, and bodyguard

Hephaestion

, the son of a Macedonian

noble.Hephaestion’s death devastated Alexander.This event may have contributed

to Alexander’s failing health and detached

mental state

during his final months.

Alexander married twice:

Roxana

, daughter of the

Bactrian

nobleman

Oxyartes

, out of love; and

Stateira II

, a Persian princess and daughter of

Darius III

of Persia, for political reasons. He

apparently had two sons, Alexander IV of Macedon of Roxana and, possibly,

Heracles of Macedon

from his mistress Barsine.

He lost another child when Roxana miscarried at Babylon.

Alexander’s sexuality has been the subject of speculation and controversy. No

ancient sources stated that Alexander had

homosexual

relationships, or that Alexander’s

relationship with Hephaestion was sexual. Aelian, however, writes of Alexander’s

visit to Troy

where “Alexander garlanded the tomb of

Achilles and Hephaestion that of

Patroclus

, the latter riddling that he was a

beloved of Alexander, in just the same way as Patroclus was of Achilles”. Noting

that the word

eromenos

(ancient Greek for beloved) does

not necessarily bear sexual meaning, Alexander may have been bisexual, which in

his time was not controversial.

Influence on Rome

Alexander and his exploits were admired by many Romans, especially generals,

who wanted to associate themselves with his achievements.

Pompey the Great

adopted the epithet “Magnus”

and even Alexander’s anatole-type haircut, and searched the conquered lands of

the east for Alexander’s 260-year-old cloak, which he then wore as a sign of

greatness.

Julius Caesar

dedicated a

Lysippean

equestrian

bronze

statue but replaced Alexander’s head

with his own, while

Octavian

visited Alexander’s tomb in Alexandria

and temporarily changed his seal from a

sphinx

to Alexander’s profile. The emperor

Trajan

also admired Alexander, as did

Nero and

Caracalla

.The Macriani, a Roman family that in

the person of Macrinus

briefly ascended to the imperial

throne, kept images of Alexander on their persons, either on jewelry, or

embroidered into their clothes.

Alexander the Great’s accomplishments and legacy have been depicted in many

cultures. Alexander has figured in both high and popular culture beginning in

his own era to the present day. The Alexander Romance, in particular, has

had a significant impact on portrayals of Alexander in later cultures, from

Persian to medieval European to modern Greek.

The army

of the

Kingdom of Macedonia

was among the greatest

military forces of the ancient world. It became formidable under King

Philip II of Macedon

and his son,

Alexander the Great

.

The latest innovations in weapons and tactics, along with unique combination

of military elements introduced by Philip II, came together into the army that

won an intercontinental empire. By introducing military service as a full-time

occupation, Philip was able to drill his men regularly, ensuring unity and

cohesion in his ranks. In a remarkably short time, this led to one of the finest

military machines that Asia

or

Greece

had ever seen.

Tactical innovations included adaptations of the latest tactics applied to

the traditional Greek

phalanx

by men such as

Epaminondas

of Thebes (who twice defeated the

Spartans), as well as coordinated attacks (early

combined arms

tactics) with the various arms of

his army — the phalanx, cavalry, missile troops and, under Alexander III,

siege engines

. A novel weapon was introduced,

the sarissa

, a type of counter-weighted (like all

Greek spears)

pike

, which gave its wielder many advantages

both offensively and defensively. For the first time in Greek warfare, cavalry

became a decisive arm in battle.

The new Macedonian army was an amalgamation of different forces. Macedonians

and other Greeks (especially

Thessalian

cavalry) and a wide range of

mercenaries from across the

Aegean

and Balkans were employed by Phillip. By

338 BC, more than a half of the army for his planned invasion of

Persia

came from outside the borders of

Macedon

— from all over the Greek world and the

nearby barbarian tribes.

Unfortunately, the primary historical sources for this period have been lost.

As a consequence, scholarship is largely reliant on the writings of

Diodorus Siculus

and

Arrian

, both of whom lived centuries later than

the events they describe.

Origins

Philip II of Macedon – silver tetradrachm coin.

If Philip II had not been the father of Alexander the Great, he would be more

widely known as a first-rate military innovator, tactician and strategist, and

as a consummate politician. The conquests of Alexander would have been

impossible without the army his father created. Considered semi-barbarous by the

metropolitan Greeks, the Macedonians were a martial people; they drank deeply of

unwatered wine (the very mark of a barbarian) and no youth was considered to be

fit to sit with the men at table until he had killed, on foot with a spear, a

wild boar.[2]

When Philip took over control of Macedon, it was a backward state on the

fringes of the Greek world and was beset by its traditional enemies: Illyrians,

Paeonians and Thracians. Macedon itself was not unified, it consisted of a

heartland inhabited by the Macedonians proper and many highland ‘baronies’

peopled by tribesmen ruled by semi-hellenised chieftains who recognised the

power of the king only when it was in their interest. Previous kings of Macedon

had raised armies including good quality cavalry, a small number of

hoplite

infantry and fairly numerous light

infantry; however, these forces were not rigorously trained or organised and

were only just capable of keeping Macedon intact — the kingdom often being

raided or invaded by the surrounding barbarian peoples.

Philip’s first achievement was to unify Macedon through his army. He raised

troops and made his army the single fount of wealth, honour and power in the

land; the unruly chieftains of Macedonia became the officers and elite

cavalrymen of the army, the highland peasants became the footsoldiers. Philip

took pains to keep them always under arms and either fighting or drilling.

Manoeuvres and drills were made into competitive events, and the truculent

Macedonians vied with each other to excel.[3]

As a political counterbalance to the native-born Macedonian nobility, Philip

invited military families from throughout Greece to settle on lands he had

conquered or confiscated from his enemies, these ‘personal clients’ then also

served in the Companion cavalry. After taking control of the gold-rich mines of

Mount Pangaeus, and the city of

Amphipolis

that dominated the region, he

obtained the wealth to support a large army, moreover it was a professional army

imbued with a national spirit. By the time of his death, Philip’s army had

pushed the Macedonian frontier into southern Illyria, conquered the Paeonians

and Thracians, destroyed the power of

Phocis

and defeated and humbled

Athens

and

Thebes

. All the states of Greece, with the

exception of Sparta, Epirus and Crete, had become subservient allies of Macedon

(League

of Corinth) and Philip was laying the foundations of an invasion of

the Persian Empire, an invasion that his son would successfully undertake.[4]

One important military innovation of Philip II is often overlooked, he banned

the use of wheeled transport and limited the number of camp servants to one to

every ten infantrymen and one each for the cavalry. This reform made the baggage

train of the army very small for its size and improved its speed of march.[5]

Troop types

and unit organisation

Ancient depiction of a Macedonian cavalryman (left). This shows

Alexander the Great as a cavalryman. He wears a helmet in the form

of the lion-scalp of Herakles. Detail of the so-called

Alexander Sarcophagus

, excavated at

Sidon.

Heavy Cavalry

The Companion Cavalry

The Companion cavalry, or

Hetairoi

(Ἑταῖροι),

were the elite arm of the Macedonian army, and have been regarded as the best

cavalry[6]

in the

ancient world

. Along with Thessalian cavalry

contingents, the Companions—raised from landed nobility—made up the bulk of the

Macedonian heavy cavalry. Central Macedonia was good horse-rearing country and

cavalry was prominent in Macedonian armies from early times. However, it was the

reforms in organisation, drill and tactics introduced by Philip II that

transformed the Companion cavalry into a battle-winning force.

The term hetairos became an

aulic title

in the

Diadochi

period, and the hetairoi were

divided into squadrons called ilai (singular: ilē), each 200 men

strong, except for the Royal Squadron, which numbered 300. The Royal Squadron

was also known as the Agema – “that which leads.” Each squadron was

commanded by an ilarchēs (ilarch) and appears to have been raised from a

particular area of Macedon. Arrian for instance described squadrons from

Bottiaea, Amphipolis, Apollonia and Anthemus.[7]

It is probable that Alexander took 8 squadrons with him on his invasion of Asia

totalling 1,800 men, leaving 7 ilai behind in Macedon (the 1,500

cavalrymen mentioned by Diodorus).[8]

Between 330 BC and 328 BC the Companions were reformed into regiments

(hipparchies) of 2-3 squadrons. In conjunction with this each squadron was

divided into two lochoi. This was probably undertaken to allow for the increase

in size of each squadron, as reinforcements and amalgamations meant the

Companion cavalry grew in size. At this time, Alexander abandoned the regional

organisation of the ilai, choosing their officers regardless of their origins.[9]

The individual Companion cavalry squadron was usually deployed in a wedge

formation, which facilitated both manoeuvrability and the shock of the charge.

The advantage of the wedge was that it offered a narrow point for piercing enemy

formations and concentrated the leaders at the front. It was easier to turn than

a square formation because everyone followed the leader at the apex, “like a

flight of cranes.” Philip II introduced the formation, probably in emulation of

Thracian and Scythian cavalry, though the example of the rhomboid formation

adopted by Macedon’s southern neighbours, the Thessalians, must also have had

some effect.[10]

The primary weapon of the Macedonian cavalry was the

xyston

, a double ended lance, with a sword as a

secondary weapon. From descriptions of combat, it would appear that once in

melee the Companion cavalryman used his lance to thrust at the chests and faces

of the enemy. It is possible that the lance was aimed at the upper body of an

opposing cavalryman in the expectation that a blow which did not wound or kill

might have sufficient leverage to unseat. If the lance broke, the Companion

could reverse it and use the other end, or draw his sword.

Cleitus

, an officer of the Companions, saved

Alexander the Great’s life at the Granicus by cutting off an enemy horseman’s

arm with his sword.[11]

Companion cavalrymen would normally have worn armour and a helmet in battle.

Although the Companion cavalry is largely regarded as the first real shock

cavalry of Antiquity, it seems that Alexander was very wary of using it against

well-formed infantry, as attested by Arrian in his account of the battle against

the Malli, an Indian tribe he faced after Hydaspes. There, Alexander did not

dare assault the dense infantry formation with his cavalry, but rather waited

for his infantry to arrive, while he and his cavalry harassed their flanks. It

is a common mistake to portray the Companion cavalry as a force able to burst

through compact infantry lines. Alexander usually launched the Companions at the

enemy after a gap had opened up between their units or disorder had already

disrupted their ranks. The Companions that accompanied Alexander to Asia

numbered 1,800 men. This number steadily grew as the campaign progressed, with

300 reinforcements arrving from Macedon after the first year of campaigning.

They were usually arrayed on the right flank (this being the position of honour

in Hellenic armies, where the best troops would be positioned), and typically

carried out the decisive maneuver/assault of the battle under Alexander’s direct

leadership.[12]

Thessalian Cavalry

A heavy cavalryman of Alexander the Great’s army, possibly a

Thessalian. He wears a cuirass (probably a linothorax) and a

Boeotian helmet, and is equipped with a scabbarded xiphos

straight-bladed sword. Alexander Sarcophagus.

Following the defeat of Lycophron of

Pherae

and

Onomarchos

of

Phocis

, Philip II of Macedon was appointed

Archon of the

Thessalian League

; his death induced the

Thessalians to attempt to throw off Macedonian hegemony, but a short bloodless

campaign by Alexander restored them to allegiance. The Thessalians were

considered the finest cavalry of Greece.

The Thessalian heavy cavalry accompanied Alexander during the first half of

his Asian campaign and was at times employed by the Macedonians as allies

throughout the later years until

Macedon

‘s final demise under the Roman gladius.

Its organization and weaponry were similar to the Companion Cavalry. However,

shorter spears and javelins were wielded in addition to the

xyston

. The Thessalian cavalry was famed for

its use of

rhomboid formations

, said to have been

developed by the Thessalian Tagos (head of the Thessalian League)

Jason of Pherae

. This formation was very

efficient for manoeuvring, as it allowed the squadron to change direction at

speed while still retaining cohesion.[13]

The numbers given for Alexander’s invasion of the

Persian Empire

included 1,800 such men. This

number would have risen no higher than 2,000. They were typically entrusted with

the defensive role of guarding the left flank from enemy cavalry, allowing the

decisive attack to be launched on the right. They often faced tremendous

opposition when in this role. At

Issus

and

Gaugamela

, the Thessalians withstood the attack

of Persian cavalry forces, though greatly outnumbered.

At Ecbatana, the Thessalians with Alexander’s army were mustered out and sent

home. Some remained with the army as mercenaries yet these too were sent home a

year later when the army reached the

Oxus River

.

Other Greek cavalry

The Hellenic states allied to, or more accurately under the hegemony of,

Macedon provided contingents of heavy cavalry and the Macedonian kings hired

mercenaries of the same origins. Alexander had 600 Greek cavalrymen at the start

of his campaign against Persia, probably organised into 5 ilai. These

cavalrymen would have been equipped very similarly to the Thessalians and

Companions, but they deployed in a square formation eight deep and sixteen

abreast.[8]

The Greek cavalry was not considered as effective or versatile as the Thessalian

and Macedonian cavalry.

Light Cavalry

Light cavalry, such as the Prodromoi, secured the wings of the army

during battle and went on

reconnaissance

missions. Apart from the

Prodromoi, other horsemen from subject or allied nations, raised from a variety

of places, filling various tactical roles and wielding different weapons,

rounded out the cavalry. By the time Alexander campaigned in India and

subsequently, the cavalry had been drastically reformed and included thousands

of horse-archers from Iranian peoples such as the

Dahae

(prominent at the

Battle of Hydaspes

), other mounted missile

troops, plus Asiatic heavy cavalry.

Prodromoi

The Prodromoi were Macedonians, they are sometimes referred to as

Sarissophoroi, or “lancers”, which leads to the conclusion that they sometimes

were armed with an uncommonly long xyston (believed to be 14 ft long), though

certainly not an infantry pike. They acted as scouts reconnoitering in front of

the army when it was on the march. In battle, they were used in a shock role to

protect the right flank of the Companion cavalry. Their abilities as scouts

would seem to have been mediocre because when Persian light cavalry were

recruited into the Macedonian army following Gaugamela they took over these

duties, with the Prodromoi assuming a purely battlefield role as shock cavalry.

Four ilai, each 150 strong, of Prodromoi operated with Alexander’s army in Asia.[14]

Paeonian cavalry

These light cavalry were recruited from

Paeonia

, a tribal region to the north of

Macedonia. The Paeones had been reduced to tributary status by Philip II. Led by

their own chieftains, the Paeonian cavalry was usually brigaded with the

Prodromoi and often operated alongside them in battle. They appear to have been

armed with javelins and swords. Initially only one squadron strong, they

received 500 reinforcements in Egypt and a further 600 at Susa.[15]

Thracian cavalry

Javelin-armed Thracian horseman – hunting wild boar.

Largely recruited from the Odrysian tribe, the Thracian cavalry also acted as

scouts on the march. In battle, they performed much the same function as the

Prodromoi and Paeonians, except they guarded the flank of the Thessalian cavalry

on the left wing of the army. The Thracians deployed in their ancestral wedge

formations and were armed with javelins and swords. At Gaugamela, the Thracians

fielded 4 ilai and were about 500 strong.[15]

Horse Archers

In 329 BC, Alexander, while in

Sogdiana

, created a 1,000 strong unit of horse

archers that was recruited from various Iranian peoples. They were very

effective at scouting and in screening the rest of the army from the enemy.

Firing their bows whilst mounted, they offered highly mobile missile fire on the

battlefield. At the Battle of Hydaspes, the massed fire of the horse archers was

effective at disordering the Indian cavalry and helped to neutralise the Indian

chariots.[16]

Infantry

The Macedonian foot soldiers were formed into an

infantry

formation

developed by

Philip II

and used by his son

Alexander the Great

to conquer the

Persian Empire

and other enemies. These

infantrymen were called

Pezhetairoi

— the Foot Companions — and

made up the dreaded Macedonian phalanx.

Philip II spent much of his youth as a hostage at

Thebes

, where he studied under the renowned

general Epaminondas

, whose reforms were the basis for a

good part of Philip’s tactics. However, the introduction of the

sarissa

pike, heavier armour and a smaller

shield seem to have been innovations devised by Philip himself. Diodorus claimed

that Philip was inspired to make changes in the organisation of his Macedonian

infantry from reading a passage in the writings of

Homer

describing a close-packed formation.[17]

Foot Companions were levied from the peasantry of Macedon. Once levied they

became professional soldiers. Discharge could only be granted by the King. Under

Philip the Foot Companions received no regular pay. This seems to have changed

by Alexander’s time as during the mutiny at Opis in 324 BC the men were

chastised by Alexander for having run up debts despite earning “good pay”.[18]

Through extensive drilling and training, the Foot Companions were able to

execute complex manoeuvres well beyond the reach of most contemporary armies.

The sound of myriads of pikes moving though the air in unison, as they were

deployed, was said to be most impressive, and very demoralising to the ears of

enemy troops.

A drawing of a Macedonian phalanx. The shields depicted are smaller

and lighter than those employed in a traditional hoplite phalanx,

the sarissa

is twice as long as the

hoplite spear and fully enclosed helmets weren’t as widespread as

this drawing suggests.)

The size of the phalanx fielded by Macedon and its various successor states

varied greatly. Alexander the Great, for example, fielded 9,000 Foot Companions

throughout much of his campaign. These were divided into 1,500-man battalions,

each raised from a separate district of Macedon.

Philip V

fielded 16,000 phalangites at the

Battle of Cynoscephalae

, and

Perseus

reputedly fielded over 20,000 at

Pydna

.

These soldiers fought in close-ranked rectangular or square formations, of

which the smallest tactical unit was the 256 men strong syntagma or

speira. This formation typically fought eight or sixteen men deep and in a

frontage of thirty-two or sixteen men accordingly. Each file of 16 men, a

lochos

. was commanded by a

lochagos

who was in the front rank. Junior

officers, one at the rear and one in the centre, were in place to steady the

ranks and maintain the cohesion of the formation, similar to modern-day

NCOs

. The commander of the syntagma

theoretically fought at the head of the extreme far-right file. According to

Aelian

, a syntagma was accompanied by

five additional individuals to the rear: a herald (to act as a messenger), a

trumpeter (to sound out commands), an ensign (to hold the unit’s standard), an

additional officer (called ouragos), and a servant. This array of both

audial and visual communication methods helped to make sure that even in the

dust and din of battle orders could still be received and given. Six

syntagmata formed a taxis of 1,500 men commanded by a strategos,

six taxeis formed a phalanx under a phalangiarch.[19]

Each phalangite carried as his primary weapon a sarissa, which was a

type of

pike

. The length of these pikes was such that

they had to be wielded with two hands in battle. The traditional Greek hoplite

used his spear single-handed, as the large hoplon shield needed to be

gripped by the left hand, therefore the Macedonian phalangite gained in both

weapon reach and in the added force of a two handed thrust. At close range, such

large weapons were of little use, but an intact phalanx could easily keep its

enemies at a distance; the weapons of the first five rows of men all projected

beyond the front of the formation, so that there were more spearpoints than

available targets at any given time. The men of the rear ranks raised their

sarissas so as to provide protection from aerial missiles. A phalangite also

carried a sword as a secondary weapon for close quarter fighting should the

phalanx disintegrate. The phalanx, however, was extremely vulnerable in the

flanks and rear.[20]

Alexander did not actually use the phalanx as the decisive arm of his

battles, but instead used it to pin and demoralize the enemy while his heavy

cavalry

would charge selected opponents or

exposed enemy unit flanks, most usually after driving the enemy horse from the

field. An example of this is the

Battle of Gaugamela

, where, after maneuvering

to the right to prevent a double envelopment from the Persian army and making

Darius command his cavalry on his left flank to check the oblique movement of

the Greeks by attacking their cavalry,

Companion cavalry

charged the weakened enemy

center where Darius was posted and were followed by the

hypaspists

and the phalanx proper.

The phalanx carried with it a fairly minimal baggage train, with only one

servant

for every ten men. This gave it a

marching

speed

that contemporary

armies could not hope to match — on occasion forces surrendered to

Alexander simply because they were not expecting him to show up for several more

days. This was made possible thanks to the training Philip instilled in his

army, which included regular forced marches.

The Macedonian phalanx itself was thus not very different from the hoplite

phalanx of other Greek states as a formation. As an evolution of the hoplite

phalanx, it featured improved equipment, training, and tactics. In Philip’s and

Alexander’s time, the Macedonian phalanx had clear technical superiority.

Ancient depiction of a Macedonian infantryman (right). He is

equipped with a hoplon (Argive) shield, so probably is a

Hypaspist. He also wears a

linothorax

cuirass and a

Thracian helmet

.

Alexander Sarcophagus

.

Hypaspists

The Hypaspists

(Hypaspistai) were the

elite

arm of the Macedonian infantry. The word

‘hypaspists’ translates into English as ‘shield-bearers’. During a pitched

battle, such as

Gaugamela

, they acted as guard for the right

flank of the phalanx and as a flexible link between the phalanx and the

Companion cavalry. They were used for a variety of irregular missions by

Alexander, often in conjunction with the

Agrianians

(elite skirmishers), the Companions

and select units of phalangites. They were prominent in accounts of Alexander’s

siege assaults in close proximity to Alexander himself. The Hypaspists were of

privileged Macedonian blood and their senior chiliarchy formed the Agema[21]

foot bodyguard of Alexander III.[22]

The Hypaspist regiment was divided into three battalions (chiliarchies)

of 1,000 men, which were then further sub-divided in a manner similar to the

Foot Companions. Each battalion would be commanded by a chiliarch, with the

regiment as a whole under the command of an archihypaspist.

In terms of weaponry, they were probably equipped in the style of a

traditional Greek hoplite

with a thrusting spear or

doru

(shorter and less unwieldy than the

sarissa) and a large round shield (hoplon).[23]

As well as this, they would have carried a sword, either a

xiphos

or a

kopis

. This would have made them far better

suited to engagements where formations and cohesion had broken down, making them

well suited to siege assaults and special missions. Their armour appears to have

varied depending on the type of mission they were conducting. When taking part

in rapid forced marches or combat in broken terrain, so common in the eastern

Persian Empire

, it appears that they wore

little more than a helmet and a cloak (exomis)

so as to enhance their stamina and mobility. However, when engaging in heavy

hand to hand fighting, for instance during a siege or pitched battle, they would

have worn body armour of either linen or bronze. This variety of armaments made

them an extremely versatile force. Their numbers were kept at full strength,

despite casualties, by continual replenishment through the transfer of veteran

soldiers chosen from the phalanx.[24]

In the last years of Alexander’s reign, the Hypaspists may have been renamed

to become the

Argyraspides

, or Silver Shields. However, some

scholars believe that the Argyraspides were formed from veterans selected from

the whole phalanx.

Other Infantry

Philip’s control over the mines of northern Greece gave him access to

unprecedented (for his part of the world) wealth in

gold and silver

, and enabled him to build his famous

army. Philip and Alexander employed troops from the confederated Greek states

and hired thousands of mercenaries from various nations to round-out their

armies.

Diodorus Siculus

, a Greek

historian

, records troops as varied as allied

and mercenary

hoplites

from various Greek states, light

infantry adept at

skirmish

tactics, such as

peltasts

, recruited from various northern

Balkan peoples and from Greece,

Cretan archers

, and

artillerists

. Spearmen from

Pontus

and

Phrygia

were also employed.[25]

These mixed troops provided added strength and flexibility throughout

Alexander’s conquests.

Concentrated missile fire from light infantry was used by Alexander to

counter both scythed chariots and war elephants.

Greek hoplites

The army led by Alexander the Great into the Persian Empire included Greek

heavy infantry in the form of allied contingents provided by the League of

Corinth and hired mercenaries. These infantrymen would have been equipped as

hoplites with the traditional hoplite panoply consisting of a thrusting spear (doru),

bronze-faced hoplon shield and body armour. In appearance, they would

have been almost identical to the hypaspists. In battle, the Greek hoplites had

a less active role than the Macedonian phalangites and hypaspists. At Gaugamela,

the Greek infantry formed the defensive rear of the box formation Alexander

arranged his army into, while the Macedonians formed its front face.

Nevertheless, they performed a valuable function in facing down attempts by the

Persian cavalry to surround the Macedonian army and helped deal with the

breakthrough of some Persian horsemen who went on to attack the baggage.

Peltasts

Agrianian peltast – modern illustration

The peltasts raised from the

Agrianes

, a

Paeonian

tribe, were the elite light infantry

of the Macedonian army. They were often used to cover the right flank of the

army in battle, being posted to the right of the Companion cavalry, a position

of considerable honour. They were almost invariably part of any force on

detached duty, especially missions requiring speed of movement.[26]

Other nationalities also provided peltasts for the Macedonian army. Especially

numerous were the Thracians; the Thracian peltasts performed the same function

in battle as the Agrianians, but for the left wing of the army.

Peltasts were armed with a number of javelins and a sword, carried a light

shield but wore no armour, though they sometimes had helmets; they were adept at

skirmishing and were often used to guard the flanks of more heavily equipped

infantry. They usually adopted an open order when facing enemy heavy infantry.

They could throw their javelins at will at the enemy and, unencumbered by armour

or heavy shields, easily evade any counter-charges made by heavily equipped

hoplites. They were, however, quite vulnerable to shock-capable cavalry and

often operated to particular advantage on broken ground where cavalry was

useless and heavy infantry found it difficult to maintain formation.[27][28]

Archers

In most Greek states, archery was not greatly esteemed, nor practiced by

native soldiery, and foreign archers were often employed, such as the Scythians

prominent in Athenian employ. However, Crete was notable for its very effective

archers, whose services as mercenaries were in great demand throughout the Greek

World. Cretan archers were famed for their powerful bows, firing arrows with

large, heavy heads of cast bronze. They carried their arrows in a

quiver

with a protective flap over its opening.

Cretan archers were unusual in carrying a shield, which was relatively small and

faced in bronze. The carrying of shields indicates that the Cretans also had

some ability in hand to hand fighting, an additional factor in their popularity

as mercenaries.[29]

Archers were also raised from Macedonia and various Balkan peoples.

Arms and Armour

Weapons

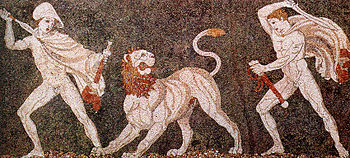

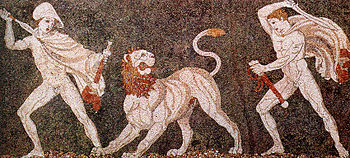

The hunter on the right is wielding a

kopis

cutting sword, the hunter

on the left holds a scabbarded

xiphos

straight sword. Both

types of sword were used by Macedonian cavalry and infantry. Lion

Hunt mosaic from the Macedonian capital Pella.

Most troops would have carried a type of sword as a secondary weapon. The

straight-bladed shortsword known as the

xiphos

(ξίφος) is depicted in works of art, and

two types of single-edged cutting swords, the

kopis

and

machaira

, are shown in images and are mentioned

in texts. The cutting swords are particularly associated with cavalry use,

especially by Xenophon

, but representations would suggest

that all three sword types were used by cavalry and infantry without obvious

distinction.[30]

Each Companion cavalryman was equipped with a 3 metre double ended

spear/lance with a cornel wood shaft called the

xyston

. The double end meant that should

the xyston break during a battle the rider need only turn his xyston around to

re-arm himself. The Thessalian and Greek cavalry would have been armed similarly

to the Companions, though the Thessalians also used javelins. The xyston was

used to thrust either overarm or underarm with the elbow flexed.[31]

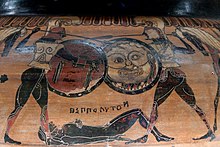

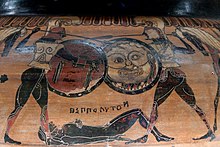

This is usefully illustrated in the Alexander Mosaic, King Alexander is shown

thrusting with his xyston underarm, whilst immediately behind him a cavalryman

is employing the overarm thrust. The shaft of the xyston was tapered allowing

the point of balance, and therefore the hand grip, to be approximately two

thirds of the length of the spear away from the point. During the reign of

Alexander the Great cavalrymen did not carry shields. However, the Companion

cavalry of the

Antigonid dynasty

did carry large, round bossed

shields of Thracian origin.

The armament of the Phalangites is described in the

Military Decree of Amphipolis

. It lists the

fines imposed upon the soldiers who fail to maintain their armament or produce

it upon demand. Offensive weapons were a pike (sarissa),

and a short sword (machaira).

The sarissa was over 6 m (18 ft) in length, with a counterweight and spiked end

at the rear called a sauroter; it seems to have had an iron sleeve in the middle

which may mean that it was in two pieces for the march with the sleeve joining

the two sections before use. It should be stressed that the archaeological

discoveries show that the phalangites also used the two-edged sword (xiphos)

as well as the traditional Greek

hoplite

spear (doru/δόρυ),

which was much shorter than the sarissa. The sources also indicate that

the phalangites were on occasion armed with javelins. The sarissa would have

been useless in siege warfare and other combat situations requiring a less

cumbersome weapon.[32]

Hypaspists and allied and mercenary Greek heavy infantry were equipped as

classic hoplites and would have employed the hoplite spear and a sword.

Light troops were provided by a number of subject and allied peoples. Various

Balkan peoples such as Agrianes, Paeonians and Thracians provided either light

infantry or cavalry or indeed both. Typical light infantry

peltasts

would be armed with a number of

javelins. The individual javelin would have a throwing thong attached to the

shaft at or near its point of balance. The thong was wound around the shaft and

hooked over one or two fingers. The thong made the javelin spin in flight, which

improved accuracy, and the extra leverage increased the range achievable.

Foot archers, notably mercenary Cretans, were also employed; Cretans were

noted for the heavy, large-headed arrows they used. Light cavalry could use

lighter types of lance, javelins and, in the case of Iranian horse archers,

compact composite bows.

Helmets

A simple conical helmet (pilos)

of a type worn by some Macedonian infantrymen.

A

Thracian helmet

. It lacks its cheek

pieces.

Virtually all helmets in use in the Greek world of the period were

constructed of bronze. One helmet prominent in contemporary images was in the

form of a

Phrygian cap

, that is it had a high and

forward-projecting apex, this type of helmet, also known as a “Thracian

helmet“, had a projecting peak above the eyes and usually had large

cheek pieces which were often decorated with stylised beards in embossing. Late

versions of the

Chalcidian helmet

were still in use; this

helmet was a lightened form developed from the

Corinthian helmet

, it had a nasal protection

and modest-sized cheek pieces. Other, more simple, helmets of the conical

‘konos’ or ‘Pilos

type‘, without cheek pieces, were also employed. These helmets were

worn by the heavy infantry.[33]

The Thracian helmet was worn by Macedonian cavalry in King Philip’s day, but

his son Alexander is said to have preferred the open-faced

Boeotian helmet

for his cavalry, as recommended

by Xenophon

.[34]

The royal burial in the

Vergina

Tomb contained a helmet which was a

variation on the Thracian/Phrygian type, exceptionally made of iron, this would

support its use by cavalry.[35]

The Boeotian helmet, though it did not have cheek pieces, had a flaring rim

which was folded into a complex shape offering considerable protection to the

face. The Alexander Mosaic suggests that officers of the heavy cavalry had rank

badges in the form of laurel wreaths (perhaps painted or of metallic

construction) on their helmets.[36]

The Alexander Sarcophagus shows Alexander the Great wearing an elaborate

helmet in the form of the lion scalp of

Herakles

. Alexander’s cousin

Pyrrhus of Epirus

is described as wearing a

helmet with cheek pieces in the shape of ram’s heads. Many examples of helmets

from the period have crest or plume-holders attached, so that a high degree of

martial finery could be achieved by the wearing of imposing headpieces.[37]

Body Armour

Alexander the Great in battle. The king wears a composite cuirass

which copies the shape of the linothorax. The shoulder elements and

upper chest are of plate iron, whilst the waist is composed of scale

armour for ease of movement. There are pteruges of leather or

stiffened linen at the shoulders and hips. The king wears a xiphos

sword. Detail of the Alexander Mosaic (A Roman copy of a Hellenistic

painting).

Body armour in the Macedonian army was derived from a repertiore found

throughout the Greek-speaking world. The most common form of armour was the

linothorax

, which was a cuirass of stiff