|

Andronicus II , Palaeologus – Byzantine Emperor: 11 December 1282 – 24 May 1328

A.D.

Andronicus II and Michael IX: Joint Rule: 1295-1320 A.D.

Bronze 19mm (2.26 grams) Constantinople mint 1295-1320 A.D.

Reference: Sear 2440, Gr.1488

Andronicus II left and Michael IX right, standing holding labarum between

them.

AVTOKPATOPЄC POMAIWN in four lines.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

Labarum of Constantine I, displaying the “Chi-Rho” symbol above.

The labarum was a

vexillum

(military standard) that displayed

the “Chi-Rho”

symbol

☧

, formed from the first two

Greek letters

of the word “Christ”

—

Chi

and

Rho

. It was first used by the

Roman emperor

Constantine I

. Since the vexillum consisted of

a flag suspended from the crossbar of a cross, it was ideally suited to

symbolize the

crucifixion

of

Christ

.

Later usage has sometimes regarded the terms “labarum” and “Chi-Rho” as

synonyms. Ancient sources, however, draw an unambiguous distinction between the

two.

Etymology

Beyond its derivation from Latin labarum, the etymology of the word is

unclear. Some derive it from Latin /labāre/ ‘to totter, to waver’ (in the sense

of the “waving” of a flag in the breeze) or laureum [vexillum] (“laurel

standard”). According to the

Real Academia Española

, the related

lábaro

is also derived from Latin labărum

but offers no further derivation from within Latin, as does the Oxford English

Dictionary.[5]

An origin as a loan into Latin from a Celtic language or

Basque

has also been postulated. There is a

traditional Basque symbol called the

lauburu

; though the name is only attested from

the 19th century onwards the motif occurs in engravings dating as early as the

2nd century AD.

Vision of Constantine

A coin of Constantine (c.337) showing a depiction of his labarum

spearing a serpent.

On the evening of October 27, 312, with his army preparing for the

Battle of the Milvian Bridge

, the emperor

Constantine I

claimed to have had a vision

which led him to believe he was fighting under the protection of the

Christian God

.

Lactantius

states that, in the night before the

battle, Constantine was commanded in a dream to “delineate the heavenly sign on

the shields of his soldiers”. He obeyed and marked the shields with a sign

“denoting Christ”. Lactantius describes that sign as a “staurogram”, or a

Latin cross

with its upper end rounded in a

P-like fashion, rather than the better known

Chi-Rho

sign described by

Eusebius of Caesarea

. Thus, it had both the

form of a cross and the monogram of Christ’s name from the formed letters “X”

and “P”, the first letters of Christ’s name in Greek.

From Eusebius, two accounts of a battle survive. The first, shorter one in

the

Ecclesiastical History

leaves no doubt that

God helped Constantine but doesn’t mention any vision. In his later Life of

Constantine, Eusebius gives a detailed account of a vision and stresses that

he had heard the story from the emperor himself. According to this version,

Constantine with his army was marching somewhere (Eusebius doesn’t specify the

actual location of the event, but it clearly isn’t in the camp at Rome) when he

looked up to the sun and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek

words

Ἐν Τούτῳ Νίκα

. The traditionally employed

Latin translation of the Greek is

in hoc signo vinces

— literally “In this

sign, you will conquer.” However, a direct translation from the original Greek

text of Eusebius into English gives the phrase “By this, conquer!”

At first he was unsure of the meaning of the apparition, but the following

night he had a dream in which Christ explained to him that he should use the

sign against his enemies. Eusebius then continues to describe the labarum, the

military standard used by Constantine in his later wars against

Licinius

, showing the Chi-Rho sign.

Those two accounts can hardly be reconciled with each other, though they have

been merged in popular notion into Constantine seeing the Chi-Rho sign on the

evening before the battle. Both authors agree that the sign was not readily

understandable as denoting Christ, which corresponds with the fact that there is

no certain evidence of the use of the letters chi and rho as a Christian sign

before Constantine. Its first appearance is on a Constantinian silver coin from

c. 317, which proves that Constantine did use the sign at that time, though not

very prominently. He made extensive use of the Chi-Rho and the labarum only

later in the conflict with Licinius.

The vision has been interpreted in a solar context (e.g. as a

solar halo

phenomenon), which would have been

reshaped to fit with the Christian beliefs of the later Constantine.

An alternate explanation of the intersecting celestial symbol has been

advanced by George Latura, which claims that Plato’s visible god in Timaeus

is in fact the intersection of the Milky Way and the Zodiacal Light, a rare

apparition important to pagan beliefs that Christian bishops reinvented as a

Christian symbol.

Eusebius’ description of the labarum

“A Description of the Standard of the Cross, which the Romans now call the

Labarum.” “Now it was made in the following manner. A long spear, overlaid with

gold, formed the figure of the cross by means of a transverse bar laid over it.

On the top of the whole was fixed a wreath of gold and precious stones; and

within this, the symbol of the Saviour’s name, two letters indicating the name

of Christ by means of its initial characters, the letter P being intersected by

X in its centre: and these letters the emperor was in the habit of wearing on

his helmet at a later period. From the cross-bar of the spear was suspended a

cloth, a royal piece, covered with a profuse embroidery of most brilliant

precious stones; and which, being also richly interlaced with gold, presented an

indescribable degree of beauty to the beholder. This banner was of a square

form, and the upright staff, whose lower section was of great length, of the

pious emperor and his children on its upper part, beneath the trophy of the

cross, and immediately above the embroidered banner.”

“The emperor constantly made use of this sign of salvation as a safeguard

against every adverse and hostile power, and commanded that others similar to it

should be carried at the head of all his armies.”

Iconographic career under Constantine

Coin of

Vetranio

, a soldier is holding two

labara. Interestingly they differ from the labarum of Constantine in

having the Chi-Rho depicted on the cloth rather than above it, and

in having their staves decorated with

phalerae

as were earlier Roman

military unit standards.

The emperor

Honorius

holding a variant of the

labarum – the Latin phrase on the cloth means “In the name of Christ

[rendered by the Greek letters XPI] be ever victorious.”

Among a number of standards depicted on the

Arch of Constantine

, which was erected, largely

with fragments from older monuments, just three years after the battle, the

labarum does not appear. A grand opportunity for just the kind of political

propaganda that the Arch otherwise was expressly built to present was missed.

That is if Eusebius’ oath-confirmed account of Constantine’s sudden,

vision-induced, conversion can be trusted. Many historians have argued that in

the early years after the battle the emperor had not yet decided to give clear

public support to Christianity, whether from a lack of personal faith or because

of fear of religious friction. The arch’s inscription does say that the Emperor

had saved the

res publica

INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS

MENTIS MAGNITVDINE (“by greatness of mind and by instinct [or impulse]

of divinity”). As with his predecessors, sun symbolism – interpreted as

representing

Sol Invictus

(the Unconquered Sun) or

Helios

,

Apollo

or

Mithras

– is inscribed on his coinage, but in

325 and thereafter the coinage ceases to be explicitly pagan, and Sol Invictus

disappears. In his

Historia Ecclesiae

Eusebius further reports

that, after his victorious entry into Rome, Constantine had a statue of himself

erected, “holding the sign of the Savior [the cross] in his right hand.” There

are no other reports to confirm such a monument.

Whether Constantine was the first

Christian

emperor supporting a peaceful

transition to Christianity during his rule, or an undecided pagan believer until

middle age, strongly influenced in his political-religious decisions by his

Christian mother

St. Helena

, is still in dispute among

historians.

As for the labarum itself, there is little evidence for its use before 317.In

the course of Constantine’s second war against Licinius in 324, the latter

developed a superstitious dread of Constantine’s standard. During the attack of

Constantine’s troops at the

Battle of Adrianople

the guard of the labarum

standard were directed to move it to any part of the field where his soldiers

seemed to be faltering. The appearance of this talismanic object appeared to

embolden Constantine’s troops and dismay those of Licinius.At the final battle

of the war, the

Battle of Chrysopolis

, Licinius, though

prominently displaying the images of Rome’s pagan pantheon on his own battle

line, forbade his troops from actively attacking the labarum, or even looking at

it directly.[16]

Constantine felt that both Licinius and

Arius

were agents of Satan, and associated them

with the serpent described in the

Book of Revelation

(12:9).

Constantine represented Licinius as a snake on his coins.

Eusebius stated that in addition to the singular labarum of Constantine,

other similar standards (labara) were issued to the Roman army. This is

confirmed by the two labara depicted being held by a soldier on a coin of

Vetranio

(illustrated) dating from 350.

Later usage

Modern ecclesiastical labara (Southern Germany).

The emperor

Constantine Monomachos

(centre

panel of a Byzantine enamelled crown) holding a miniature labarum

Michael IX Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( Mikhaēl IX

Palaiologos), (April 17, 1277 – October 12, 1320,

Thessalonica

,

Greece

), reigned as Byzantine co-emperor with

full imperial style 1294/1295–1320. Michael IX was the eldest son of

Andronikos II Palaiologos

and

Anna of Hungary

, a daughter of King

Stephen V of Hungary

.

Life

Michael IX Palaiologos was acclaimed co-emperor in 1281 and was crowned in

1294 or 1295. In 1300, he was sent at the head of Alanian mercenaries against

the Turks in

Asia Minor

, and in 1304–1305 he was charged

with dealing with the rebellious

Catalan Company

. After the murder of the

Catalan commander

Roger de Flor

, Michael IX led the Byzantine

troops (augmented by Turks and 5–8,000 Alanians) against the Catalans, but was

defeated and wounded.

Michael IX was also ultimately unsuccessful against

Theodore Svetoslav of Bulgaria

in 1307,

concluding peace in 1307 and marrying his daughter to the Bulgarian emperor. In

1311, Michael IX was defeated by Osman I. Michael IX eventually retired to

Thessalonica

, where he died in 1320.

A brave and energetic soldier willing to make personal sacrifices to pay or

encourage his troops, Michael IX was generally unable to overcome his enemies

and is the only Palaiologan emperor to predecease his father. Michael IX’s

premature death at age 43 was attributed in part to grief over the accidental

murder of his younger son Manuel Palaiologos by retainers of his older son and

co-emperor

Andronikos III Palaiologos

.

Family

Michael IX Palaiologos married

Rita of Armenia

(renamed Maria, later nun Xene),

daughter of King

Leo III of Armenia

and

Queen Keran of Armenia

on 16 January 1294. By

this marriage, Michael IX had several children, including:

-

Andronikos III Palaiologos

- Manuel Palaiologos, despotēs

- Anna Palaiologina, who married

Thomas I Komnenos Doukas

and then

Nicholas Orsini

.

- Theodora Palaiologina, who married

Theodore Svetoslav of Bulgaria

and then

Michael Asen III of Bulgaria

.

Andronikos II Palaiologos (25

March 1259

,

Nicaea

–

February

13

, 1332

,

Constantinople

) — also Andronicus II Palaeologus — reigned as

Byzantine emperor

from 1282 to 1328. He was the eldest surviving son of

Michael VIII Palaiologos

and

Theodora Doukaina Vatatzina

, grandniece of

John III Doukas Vatatzes

.

//

Andronikos II Palaiologos was acclaimed co-emperor in 1261, after

his father Michael VIII recovered

Constantinople

from the

Latin

Empire

, but he was crowned only in 1272. Sole emperor from 1282, Andronikos

II immediately repudiated his father’s unpopular Church union with the

Papacy

(which he had been forced to support while his father was still

alive), but was unable to resolve the related schism within the Orthodox clergy

until 1310. Andronikos II was also plagued by economic difficulties and during

his reign the value of the Byzantine

hyperpyron

depreciated precipitously while the state treasury accumulated less than one

seventh the revenue (in nominal coins) that it had done previously. Seeking to

increase revenue and reduce expenses, Andronikos II raised taxes and reduced tax

exemptions, and dismantled the Byzantine fleet (80 ships) in 1285, thereby

making the Empire increasingly dependent on the rival republics of

Venice

and

Genoa

. In 1291, he hired 50-60 Genoese ships. Later, in 1320, he tried to

resurrect the navy by constructing 20 galleys, but unfortunately he failed.

Andronikos II Palaiologos sought to resolve some of the problems facing the

Byzantine Empire

through diplomacy. After the death of his first wife, he

married

Yolanda (renamed Eirene) of Montferrat

, putting an end to the Montferrat

claim to the

Kingdom of Thessalonica

. Andronikos II also attempted to marry off his son

and co-emperor

Michael IX Palaiologos

to the Latin Empress

Catherine I of Courtenay

, thus seeking to eliminate Western agitation for a

restoration of the

Latin

Empire

. Another marriage alliance attempted to resolve the potential

conflict with Serbia

in

Macedonia

, as Andronikos II married off his five-year old daughter

Simonis

to

King

Stefan Milutin

in 1298.

In spite of the resolution of problems in

Europe

,

Andronikos II was faced with the collapse of the Byzantine frontier in

Asia Minor

. After the failure of the co-emperor Michael IX to stem the

Turkish advance in Asia Minor in 1300, the Byzantine government hired the

Catalan Company

of

Almogavars

(adventurers from Aragon

and

Catalonia

)

led by

Roger

de Flor

to clear Byzantine Asia Minor of the enemy. In spite of some

successes, the Catalans were unable to secure lasting gains. They quarreled with

Michael IX, and eventually turned on their Byzantine employers after the murder

of Roger de Flor in 1305, devastating

Thrace

,

Macedonia, and Thessaly

on their road to Latin Greece. There they conquered the

Duchy of Athens

and

Thebes

. The Turks continued to penetrate the Byzantine possessions, and

Prusa

fell in 1326. By the end of Andronikos II’s reign, much of Bithynia

was in the hands of the

Ottoman Turks

of Osman I and his son and heir

Orhan

. Also,

Karesi

conquered Mysia

region with Paleokastron

after 1296, Germiyan conquered

Simav

in 1328,

Saruhan captured Magnesia

in 1313 and

Aydınoğlu

captured Symirna

in 1310.

The Empire’s problems were exploited by

Theodore Svetoslav of Bulgaria

, who defeated Michael IX and conquered much

of northeastern Thrace in c. 1305-1307. The conflict ended with yet another

dynastic marriage, between Michael IX’s daughter Theodora and the Bulgarian

emperor. The dissolute behavior of Michael IX’s son

Andronikos III Palaiologos

led to a rift in the family, and after Michael

IX’s death in 1320, Andronikos II disowned his grandson, prompting a

civil war

that raged, with interruptions, until 1328. The conflict

precipitated Bulgarian involvement, and

Michael Asen III of Bulgaria

attempted to capture Andronikos II under the

guise of sending him military support. In 1328 Andronikos III entered

Constantinople in triumph and Andronikos II was forced to abdicate. He died as a

monk in 1332.

The Byzantine Empire was

the predominantly Greek-speaking

continuation of the Roman

Empire during Late

Antiquity and the Middle

Ages. Its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul),

originally known as Byzantium.

Initially the eastern half of the Roman Empire (often called the Eastern

Roman Empire in this context), it

survived the 5th century fragmentation

and collapse of the Western

Roman Empire and continued

to thrive, existing for an additional thousand years until it fell to

the Ottoman

Turks in 1453. During most

of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and

military force in Europe. Both “Byzantine Empire” and “Eastern Roman Empire” are

historiographical terms applied in later centuries; its citizens continued to

refer to their empire as the Roman

Empire (Ancient

Greek: Βασιλεία

Ῥωμαίων, tr.Basileia

Rhōmaiōn; Latin: Imperium

Romanum), and Romania.

Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the transitional period during

which the Roman Empire’s east

and west divided.

In 285, theemperor Diocletian (r.

284–305) partitioned the Roman Empire’s administration into eastern and western

halves. Between

324 and 330,Constantine

I (r. 306–337) transferred

the main capital from Rome to Byzantium,

later known as Constantinople (“City

of Constantine”) and Nova Roma (“New

Rome”). Under Theodosius

I (r. 379–395), Christianity became

the Empire’s official state

religion and others such

as Roman

polytheism were proscribed.

And finally, under the reign of Heraclius (r.

610–641), the Empire’s military and administration were restructured and adopted

Greek for official use instead of Latin. In

summation, Byzantium is distinguished from ancient

Rome proper insofar as it

was oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by Orthodox

Christianity rather than Roman

polytheism.

The borders of the Empire evolved a great deal over its existence, as it went

through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of

Justinian I

(r.

527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the

historically Roman western Mediterranean coast,

including north Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more

centuries. During the reign of Maurice (r.

582–602), the Empire’s eastern frontier was expanded and north stabilised.

However, his assassination caused a two-decade-long

war with Sassanid

Persia which exhausted the

Empire’s resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the Muslim

conquests of the 7th

century. During the 10th-centuryMacedonian

dynasty, the Empire experienced a golden

age, which culminated in the reign of Emperor

Basil II “the Bulgar-Slayer”. However, shortly after Basil’s death, a

neglect of the vast military built up during the Late Macedonian

dynasty caused the Empire

to begin to lose territory in Asia Minor to the Seljuk

Turks. Emperor

Romanos IV Diogenes and

several of his predecessors had attempted to rid Eastern

Anatolia of the Turkish

menace, but this endeavor proved ultimately untenable – especially after the

disastrous Battle

of Manzikert in 1071.

Despite a prominent period

of revival (1081-1180) under

the steady leadership of the Komnenos

family, who played an instrumental role in theFirst and Second

Crusades, the final centuries of the Empire exhibit a general trend

of decline. In 1204, after a period

of strife following the

downfall of the Komnenos

dynasty, the Empire was delivered a mortal blow by the forces of the Fourth

Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked and the Empire dissolved

and divided into competing

Byzantine Greek and Latin

realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople and re-establishment

of the Empire in 1261, Byzantium remained only one of a number of

small rival states in the area for the final two centuries of its existence.

This volatile period lead to its progressive

annexation by the Ottomans over

the 15th century and the Fall

of Constantinople in 1453.

Nomenclature

The first use of the term “Byzantine” to label the later years of the Roman

Empire was in 1557, when

the German historian Hieronymus

Wolf published his work Corpus

Historiæ Byzantinæ, a collection of historical sources. The term comes from

“Byzantium”, the name of the city of Constantinople before it became

Constantine’s capital. This older name of the city would rarely be used from

this point onward except in historical or poetic contexts. The publication in

1648 of the Byzantine du Louvre (Corpus

Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae), and in 1680 of Du

Cange‘s Historia

Byzantina further popularised the

use of “Byzantine” among French authors, such as Montesquieu.[7] However,

it was not until the mid-19th century that the term came into general use in the

Western world. As regards the English historiography in particular, the first

occasion of the “Byzantine Empire” appears in a 1857 work of George

Finlay (History of the

Byzantine Empire from 716 to 1057).

The Byzantine Empire was known to its inhabitants as the “Roman Empire”, the

“Empire of the Romans” (Latin: Imperium

Romanum, Imperium Romanorum;

“Romania” (Latin: Romania;

the “Roman Republic” (Latin: Res

Publica Romana.

Although the Byzantine Empire had a multi-ethnic character during most of its

history and preserved Romano-Hellenistic traditions,[13] it

became identified by its western and northern contemporaries with its

increasingly predominant Greek

element. The occasional

use of the term “Empire of the Greeks” (Latin: Imperium

Graecorum) in the West to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire and of the

Byzantine Emperor as Imperator

Graecorum (Emperor of the Greeks) were

also used to separate it from the prestige of the Roman Empire within the new

kingdoms of the West.

The authority of the Byzantine emperor as the legitimate Roman emperor was

challenged by the coronation of Charlemagne as Imperator

Augustus by Pope

Leo III in the year 800.

Needing Charlemagne’s support in his struggle against his enemies in Rome, Leo

used the lack of a male occupant of the throne of the Roman Empire at the time

to claim that it was vacant and that he could therefore crown a new Emperor

himself.[17] Whenever

the Popes or the rulers of the West made use of the name Roman to

refer to the Eastern Roman Emperors, they usually preferred the term Imperator

Romaniae (meaning Emperor

of Romania) instead of Imperator

Romanorum (meaning Emperor

of the Romans), a title that they applied only to Charlemagne and his

successors.

No such distinction existed in the Persian, Islamic, and Slavic worlds, where

the Empire was more straightforwardly seen as the continuation of the Roman

Empire. In the Islamic world it was known primarily as روم (Rûm).

History

Early history

The Baptism of Constantine painted

byRaphael‘s

pupils (1520–1524, fresco,

Vatican City,

PalaceApostolic). Eusebius

of Caesarea records

that (as was

common among converts of early Christianity) Constantine

delayed receiving baptismuntil

shortly before his death.

The Roman

army succeeded in

conquering many territories covering the entire Mediterranean region and coastal

regions in southwestern

Europe and north Africa.

These territories were home to many different cultural groups, ranging from

primitive to highly sophisticated. Generally speaking, the eastern Mediterranean

provinces were more urbanised than the western, having previously been united

under the Macedonian

Empire and Hellenisedby

the influence of Greek culture.

The west also suffered more heavily from the instability of the 3rd century AD.

This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger

Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries,

leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.

Divisions of the

Roman Empire

In order to maintain control and improve administration, various schemes to

divide the work of the Roman Emperor by sharing it between individuals were

tried between 285 and 324, from 337 to 350, from 364 to 392, and again between

395 and 480. Although the administrative subdivisions varied, they generally

involved a division of labour between East and West. Each division was a form of

power-sharing (or even job-sharing), for the ultimateimperium was

not divisible and therefore the empire remained legally one state—although the

co-emperors often saw each other as rivals or enemies rather than partners.

In 293, emperor Diocletian created

a new administrative system (the tetrarchy),

in order to guarantee security in all endangered regions of his Empire. He

associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus),

and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of Caesar,

to share in their rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. The

tetrarchy collapsed, however, in 313 and a few years later Constantine I

reunited the two administrative divisions of the Empire as sole Augustus.

Recentralisation

In 330, Constantine moved

the seat

of the Empire to Constantinople,

which he founded as a second Rome on the site of Byzantium, a city

well-positioned astride the trade routes between East and West. Constantine

introduced important changes into the Empire’s military, monetary, civil and

religious institutions. As regards his economic policies in particular, he has

been accused by certain scholars of “reckless fiscality”, but the gold solidus he

introduced became a stable currency that transformed the economy and promoted

development.

Under Constantine, Christianity did not become the exclusive religion of the

state, but enjoyed imperial preference, because the

emperor supported it with generous privileges. Constantine

established the principle that emperors could not settle questions of doctrine

on their own, but should summon instead general

ecclesiastical councils for

that purpose. His convening of both the

of ArlesSynod and the First

Council of Nicaea indicated

his interest in the unity of the Church, and showcased his claim to be its head.

The Roman Empire during the reigns of Leo I(east) and

Majorian (west) in

460 AD. Roman rule in the west would last less than two more

decades, whereas the territory of the east would remain static until

the reconquests of Justinian I.

In 395, Theodosius

I bequeathed the imperial

office jointly to his sons: Arcadius in

the East and Honorius in

the West, once again dividing Imperial administration. In the 3rd and 4th

centuries, the Eastern part of the empire was largely spared the difficulties

faced by the West—due in part to a more established urban culture and greater

financial resources, which allowed it to placate invaders with tribute and

pay foreign mercenaries. This success allowed Theodosius

II to focus on the codification

of the Roman law and the

further fortification of the

walls of Constantinople, which left the city impervious to most

attacks until 1204.

To fend off the Huns,

Theodosius had to pay an enormous annual tribute to Attila.

His successor, Marcian,

refused to continue to pay the tribute, but Attila had already diverted his

attention to the West.

After his death in 453, the Hunnic

Empire collapsed, and many

of the remaining Huns were often hired as mercenaries by Constantinople.

Loss of the

western Roman Empire

After the fall of Attila, the Eastern Empire enjoyed a period of peace, while

the Western Empire deteriorated in continuing migration and expansion by

nationsGermanic (its end is

usually dated in 476 when the Germanic Roman general Odoacer deposed

the titular Western Emperor Romulus

Augustulus). In 480 Emperor Zeno abolished

the division of the Empire making himself sole Emperor. Odoacer, now ruler of

Italy, was nominally Zeno’s subordinate but acted with complete autonomy,

eventually providing support of a rebellion against the Emperor.

Zeno negotiated with the conquering Ostrogoths,

who had settled in Moesia,

convincing the Gothic king Theodoric to

depart for Italy as magister

militum per Italiam (“commander

in chief for Italy”) with the aim to depose Odoacer. By urging Theodoric into

conquering Italy, Zeno rid the Eastern Empire of an unruly subordinate (Odoacer)

and moved another (Theodoric) further from the heart of the Empire. After

Odoacer’s defeat in 493, Theodoric ruled Italy on his own, although he was never

recognised by the eastern emperors as “king” (rex).

In 491, Anastasius

I, an aged civil officer of Roman origin, became Emperor, but it was

not until 497 that the forces of the new emperor effectively took the measure of Isaurian

resistance.[29]Anastasius

revealed himself as an energetic reformer and an able administrator. He

perfected Constantine I’s coinage system by definitively setting the weight of

the copper follis,

the coin used in most everyday transactions.[30] He

also reformed the tax system and permanently abolished the chrysargyron tax.

The State Treasury contained the enormous sum of 320,000 lb (150,000 kg) of gold

when Anastasius died in 518.

Reconquest of

the western provinces

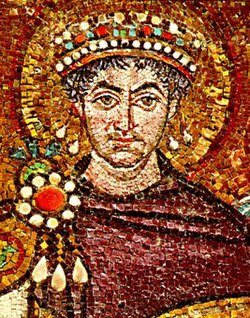

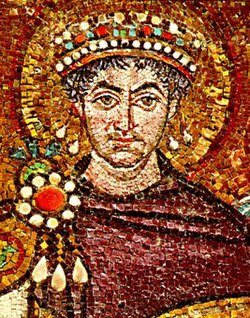

Justinian I

depicted

on one of the famous mosaics of the Basilica

of San Vitale, Ravenna.

Justinian I

, the son of an Illyrian peasant,

may already have exerted effective control during the reign of his uncle, Justin

I (518–527). He

assumed the throne in 527, and oversaw a period of recovery of former

territories. In 532, attempting to secure his eastern frontier, he signed a

peace treaty with Khosrau

I of Persia agreeing to

pay a large annual tribute to the Sassanids.

In the same year, he survived a revolt in Constantinople (the Nika

riots), which solidified his power but ended with the deaths of a

reported 30,000 to 35,000 rioters on his orders.

In 529, a ten-man commission chaired by John

the Cappadocian revised

the Roman law and created a new codification of

laws and jurists’ extracts. In 534, the Code was

updated and, along with the enactements

promulgated by Justinian after 534, it formed the system of law used

for most of the rest of the Byzantine era.

The western conquests began in 533, as Justinian sent his general Belisarius to

reclaim the former province of Africa from

the Vandals who

had been in control since 429 with their capital at Carthage. Their

success came with surprising ease, but it was not until 548 that the major local

tribes were subdued. In Ostrogothic

Italy, the deaths of Theodoric, his nephew and heir Athalaric,

and his daughter Amalasuntha had

left her murderer,Theodahad (r.

534–536), on the throne despite his weakened authority.

In 535, a small Byzantine expedition to Sicily met

with easy success, but the Goths soon stiffened their resistance, and victory

did not come until 540, when Belisarius captured Ravenna,

after successful sieges of Naples and

Rome. In 535–536, Theodahad sent Pope

Agapetus I to

Constantinople to request the removal of Byzantine forces from Sicily, Dalmatia,

and Italy. Although Agapetus failed in his mission to sign a peace with

Justinian, he succeeded in having the Monophysite Patriarch

Anthimus I of Constantinople denounced,

despite empress Theodora‘s

support and protection.

The Ostrogoths were soon reunited under the command of King Totila and captured

Rome in 546. Belisarius,

who had been sent back to Italy in 544, was eventually recalled to

Constantinople in 549. The arrival of

the Armenian eunuch Narses in

Italy (late 551) with an army of some 35,000 men marked another shift in Gothic

fortunes. Totila was defeated at the Battle

of Taginae and his

successor, Teia,

was defeated at the Battle

of Mons Lactarius (October

552). Despite continuing resistance from a few Gothic garrisons and two

subsequent invasions by the Franks and Alemanni,

the war for the Italian peninsula was at an end. In

551, Athanagild,

a noble from Visigothic Hispania,

sought Justinian’s help in a rebellion against the king, and the emperor

dispatched a force under Liberius,

a successful military commander. The Empire held on to a small slice of the Iberian

Peninsula coast until the

reign of Heraclius.

The Eastern Roman Empire in 600 AD during the reign of Emperor

Maurice.

In the east, the Roman–Persian Wars continued until 561 when the envoys of

Justinian and Khosrau agreed on a 50-year peace. By

the mid-550s, Justinian had won victories in most theatres of operation, with

the notable exception of the Balkans,

which were subjected to repeated incursions from the Slavs and

the Gepids.

Tribes of Serbs and Croats were

later resettled in the northwestern Balkans, during the reign of Heraclius. Justinian

called Belisarius out of retirement and defeated the new Hunnish threat. The

strengthening of the Danube fleet caused the Kutrigur Huns

to withdraw and they agreed to a treaty that allowed safe passage back across

the Danube.

During the 6th century, older Hellenistic

religion and philosophy,

still influential in the east, began to be supplanted by or amalgamated into

newer Christian philosophy, with pagan

traditions suppressed by imperial order. While philosophers such as John

Philoponus drew on neoplatonic ideas

as well as Christian thought and empiricism,

the Platonic

Academy is recorded as

being closed in 529. Hymns written by Romanos

the Melodistmarked the development of the Divine

Liturgy, while architects and builders worked to complete the new

Church of the Holy

Wisdom, Hagia

Sophia, which was designed to replace an older church destroyed

during the Nika Revolt. The Hagia Sophia stands today as one of the major

monuments of Byzantine architectural history. During

the 6th and 7th centuries, the Empire was struck by a series

of epidemics, which greatly devastated the population and contributed

to a significant economic decline and a weakening of the Empire.

After Justinian died in 565, his successor, Justin

II refused to pay the

large tribute to the Persians. Meanwhile, the Germanic Lombards invaded

Italy; by the end of the century only a third of Italy was in Byzantine hands.

Justin’s successor, Tiberius

II, choosing between his enemies, awarded subsidies to the Avars while

taking military action against the Persians. Though Tiberius’ general,Maurice,

led an effective campaign on the eastern frontier, subsidies failed to restrain

the Avars. They captured the Balkan fortress of Sirmium in

582, while the Slavs began to make inroads across the Danube.Maurice, who

meanwhile succeeded Tiberius, intervened in a Persian civil war, placed the

legitimate Khosrau

II back on the throne and

married his daughter to him. Maurice’s treaty with his new brother-in-law

enlarged the territories of the Empire to the East and allowed the energetic

Emperor to focus on the Balkans. By 602, a series of successful Byzantine campaigns had

pushed the Avars and Slavs back across the Danube.

Shrinking borders

Heraclian dynasty

The Byzantine Empire in 650 – by this year it lost all of its

southern provinces except the Exarchate

of Africa.

After Maurice’s murder by Phocas,

Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer the Roman

province of Mesopotamia.Phocas, an unpopular ruler invariably

described in Byzantine sources as a “tyrant”, was the target of a number of

Senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by Heraclius, who sailed to

Constantinople from Carthage with

an icon affixed to the prow of his ship.

Following the ascension of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into Asia

Minor, occupying Damascus andJerusalem and

removing the True

Cross to Ctesiphon. The

counter-attack launched by Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an acheiropoietos image

of Christ was carried as a military standard (similarly,

when Constantinople was saved from an Avar siege in 626, the victory was

attributed to the icons of the Virgin that were led in procession by

SergiusPatriarch about the walls of

the city).

The main Sassanid force was destroyed at Nineveh in

627, and in 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic

ceremony. The war had exhausted both

the Byzantines and Sassanids, however, and left them extremely vulnerable to the Muslim

forces that emerged in the

following years. The Byzantines

suffered a crushing defeat by the Arabs at the Battle

of Yarmouk in 636, while

Ctesiphon fell in 634.

Siege of Constantinople (674–678)

The Arabs, now firmly in control

of Syria and the Levant, sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia

Minor, and in 674–678

laid siege to Constantinople itself.

The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of Greek

fire, and a thirty-years’ truce was signed between the Empire and the Umayyad

Caliphate. However, the Anatolian raids

continued unabated, and accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with

the inhabitants of many cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the

old city walls, or relocating entirely to nearby fortresses. Constantinople

itself dropped substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just

40,000–70,000, and, like other urban centres, it was partly ruralised. The city

also lost the free grain shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the

Persians and then to the Arabs, and public wheat distribution ceased.

The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions

was filled by the theme system, which entailed dividing Asia Minor into

“provinces” occupied by distinct armies that assumed civil authority and

answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its

roots in certain ad hoc measures

taken by Heraclius, but over the course of the 7th century it developed into an

entirely new system of imperial governance.[59] The

massive cultural and institutional restructuring of the Empire consequent on the

loss of territory in the 7th century has been said to have caused a decisive

break in east Mediterranean Romanness and

that the Byzantine state is subsequently best understood as another successor

state rather than a real continuation of the Roman Empire.

The Greek fire was first used by the Byzantine

Navy during

the Byzantine-Arab Wars (from the

SkylitzesMadrid, Biblioteca

Nacional de España, Madrid).

The withdrawal of large numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the

Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual

southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Asia Minor,

many cities shrank to small fortified settlements.In the 670s, theBulgars were

pushed south of the Danube by the arrival of the Khazars.

In 680, Byzantine forces sent to disperse these new settlements were defeated.

In 681, Constantine

IV signed a treaty with

the Bulgar khan Asparukh,

and the new

Bulgarian state assumed

sovereignty over a number of Slavic tribes that had previously, at least in

name, recognised Byzantine rule. In

687–688, the final Heraclian emperor, Justinian

II, led an expedition against the Slavs and Bulgarians, and made

significant gains, although the fact that he had to fight his way from Thrace to Macedonia demonstrates

the degree to which Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.[63]

Justinian II attempted to break the power of the urban aristocracy through

severe taxation and the appointment of “outsiders” to administrative posts. He

was driven from power in 695, and took shelter first with the Khazars and then

with the Bulgarians. In 705, he returned to Constantinople with the armies of

the Bulgarian khan Tervel,

retook the throne, and instituted a reign of terror against his enemies. With

his final overthrow in 711, supported once more by the urban aristocracy, the

Heraclian dynasty came to an end.

Isaurian dynasty to the ascension of Basil I

The Byzantine Empire at the accession of Leo III, c. 717. Striped

area indicates land raided by the Arabs.

Leo III the Isaurian

turned

back the Muslim assault in 718 and addressed himself to the task of reorganising

and consolidating the themes in Asia Minor. His successor, Constantine

V, won noteworthy victories in northern Syria and thoroughly

undermined Bulgarian strength.

Taking advantage of the Empire’s weakness after the Revolt

of Thomas the Slav in the

early 820s, the Arabs reemerged and

Cretecaptured. They also successfully attacked Sicily, but in 863 general Petronas gained

a huge

victory against Umar

al-Aqta, the emir of Melitene.

Under the leadership of emperor Krum,

the Bulgarian threat also reemerged, but in 815–816 Krum’s son, Omurtag,

signed a peace

treaty with Leo

V.

Religious

dispute over iconoclasm

The 8th and early 9th centuries were also dominated by controversy and religious

division over Iconoclasm,

which was the main political issue in the Empire for over a century. Icons (here

meaning all forms of religious imagery) were banned by Leo and Constantine from

around 730, leading to revolts by iconodules (supporters

of icons) throughout the empire. After the efforts of empress Irene,

the Second

Council of Nicaea met in

787 and affirmed that icons could be venerated but not worshiped. Irene is said

to have endeavoured to negotiate a marriage between herself and Charlemagne,

but, according to Theophanes

the Confessor, the scheme was frustrated by Aetios, one of her

favourites.

In the early 9th century, Leo V reintroduced the policy of iconoclasm, but in

843 empress Theodora restored

the veneration of icons with the help of Patriarch

Methodios.Iconoclasm played a part in the further alienation of East

from West, which worsened during the so-called Photian

schism, when Pope

Nicholas I challenged the

elevation of Photios to

the patriarchate.

Legacy

King David in

robes of a Byzantine emperor. Miniature from the Paris

Psalter.

Byzantium has been often identified with absolutism, orthodox spirituality,

orientalism and exoticism, while the terms “Byzantine” and “Byzantinism” have

been used as bywords for decadence, complex bureaucracy, and repression. In the

countries of Central and

Southeast Europe that exited the

BlocEastern in late 80s and early

90s, the assessment of Byzantine civilisation and its legacy was strongly

negative due to their connection with an alleged “Eastern authoritarianism and

autocracy.” Both Eastern and Western European authors have often perceived

Byzantium as a body of religious, political, and philosophical ideas contrary to

those of the West. Even in 19th-century

Greece, the focus was mainly on the classical past, while Byzantine

tradition had been associated with negative connotations.

This traditional approach towards Byzantium has been partially or wholly

disputed and revised by modern studies, which focus on the positive aspects of

Byzantine culture and legacy. Averil

Cameron regards as

undeniable the Byzantine contribution to the formation of the medieval Europe,

and both Cameron and Obolensky recognise the major role of Byzantium in shaping

Orthodoxy, which in turn occupies a central position in the history and

societies of Greece, Bulgaria, Russia, Serbia and other countries. The

Byzantines also preserved and copied classical manuscripts, and they are thus

regarded as transmitters of the classical knowledge, as important contributors

to the modern European civilisation, and as precursors of both the Renaissance

humanism and the Slav

Orthodox culture.

As the only stable long-term state in Europe during the Middle Ages, Byzantium

isolated Western Europe from newly emerging forces to the East. Constantly under

attack, it distanced Western Europe from Persians, Arabs, Seljuk Turks, and for

a time, the Ottomans. From a different perspective, since the 7th century, the

evolution and constant reshaping of the Byzantine state were directly related to

the respective progress of Islam.

Following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Sultan Mehmed

II took the title “Kaysar-i-Rûm”

(the Turkish equivalent of Caesar of Rome), since he was determined to make the

Ottoman Empire the heir of the Eastern Roman Empire. According

to Cameron, regarding themselves as “heirs” of Byzantium, the Ottomans preserved

important aspects of its tradition, which in turn facilitated an “Orthodox

revival” during the post-communist period

of the Eastern European states.

|