|

Greek coin of the Kingdom of Macedonia

Antigonos II Gonatas – King: 277-239 B.C.

Bronze 13mm (3.12 grams) Struck circa 274-239 B.C.

Reference: Sear 6786; HGC 3, 1049; SNG Copenhagen 1205-1211

Head of Athena right, in crested Corinthian helmet.

Pan advancing right, erecting trophy of Galatian arms; B-A in upper field; ANTI monogram beneath Pan.

The English word panic is derived from the Greek deity Pan. It is said that Pan helped the Macedonian army in the battle that Antigonos had with the Gauls in 277 B.C. at the “Battle of Lysimacheia” and thus is shown on his coins erecting a trophy.

Antigonos II, Gonatas was son of Demetrios Poliorketes, and grandson of the preceding. He assumed the title of king of Macedonia after his father’s death in Asia in B.C. 283, but he did not obtain possession of the throne until 277 after achieving a notable victory over the Gallic invaders in Thrace. He was driven out of his kingdom by Pyrrhos, and again recovered his dominions. He attempted to prevent the formation of the Achaean league, and died 239. His surname Gonatas is usually derived from Gonnos or Gonni in Thessaly; but some think that Gonatas is a Macedonian word, signifying an iron plate protecting the knee. The Macedonian kingdom prospered again under his long and enlightened rule.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The Battle of Lysimachia was fought in 277 BC between the Gallic tribes settled in Thrace and a Greek army of Antigonus at Lysimachia, Thracian Chersonese. After their defeat at Thermopylae the Gauls retreated out of Greece and moved through Thrace and finally into Asia.

Antigonus father, Demetrius Poliorcetes, had been driven from the Macedonian throne by Pyrrhus of Epirus and Lysimachus in 288 BC. Tired of war Demetrius surrendered himself to Seleucus I Nicator in 285 BC, leaving Antigonus as the Antigonid heir to the Macedonian throne.

In 277 BC Antigonus organized an expedition to take Macedon from Sosthenes of Macedon. He sailed to the Hellespont, landing near Lysimachia at the neck of the Thracian Chersonese. The site of the landing was the territory of wild Gallic tribes, who had settled the place after being driven out of Greece. When an army of Gauls under the command of Cerethrius appeared, Antigonus laid an ambush. He abandoned his camp and beached his ships, then concealed his men. The Gauls looted the camp, but when they started to attack the ships, Antigonus’s army appeared, trapping them with the sea to their rear. In this way, Antigonus was able to inflict a crushing defeat on them and claim the Macedonian throne. It was around this time, under these favorable omens, that his son and successor, Demetrius II Aetolicus was born by his niece-wife Phila.

Athena or Athene (Latin: Minerva), also referred to as Pallas Athena, is the goddess of war, civilization, wisdom, strength, strategy, crafts, justice and skill in Greek mythology. Minerva, Athena’s Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is also a shrewd companion of heroes and the goddess of heroic endeavour. She is the virgin patron of Athens. The Athenians built the Parthenon on the Acropolis of her namesake city, Athens, in her honour (Athena Parthenos). Athena’s cult as the patron of Athens seems to have existed from the earliest times and was so persistent that archaic myths about her were recast to adapt to cultural changes. In her role as a protector of the city (polis), many people throughout the Greek world worshiped Athena as Athena Polias (“Athena of the city”). Athens and Athena bear etymologically connected names. Athena or Athene (Latin: Minerva), also referred to as Pallas Athena, is the goddess of war, civilization, wisdom, strength, strategy, crafts, justice and skill in Greek mythology. Minerva, Athena’s Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is also a shrewd companion of heroes and the goddess of heroic endeavour. She is the virgin patron of Athens. The Athenians built the Parthenon on the Acropolis of her namesake city, Athens, in her honour (Athena Parthenos). Athena’s cult as the patron of Athens seems to have existed from the earliest times and was so persistent that archaic myths about her were recast to adapt to cultural changes. In her role as a protector of the city (polis), many people throughout the Greek world worshiped Athena as Athena Polias (“Athena of the city”). Athens and Athena bear etymologically connected names.

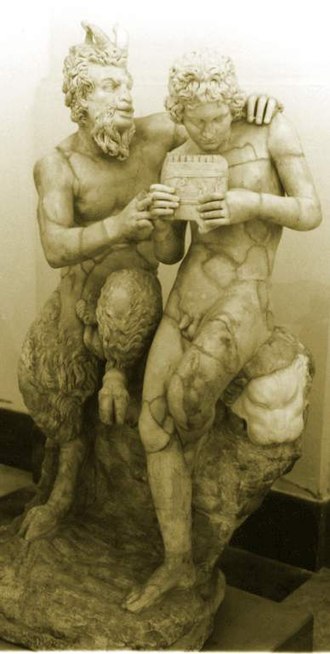

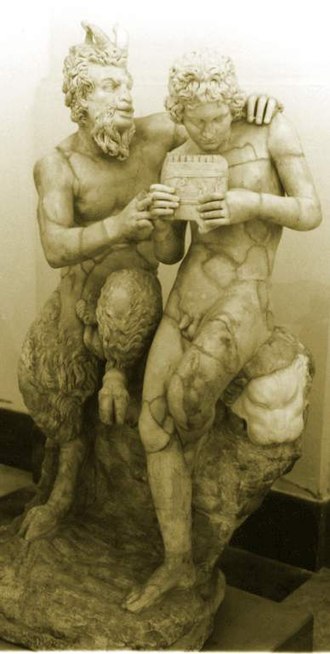

In Greek religion and mythology, Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, hunting, and rustic music, and companion of the nymphs. His name originates within the Ancient Greek language, from the word paein (πάειν), meaning “to pasture.” He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr. With his homeland in rustic Arcadia, he is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, and wooded glens; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring. The ancient Greeks also considered Pan to be the god of theatrical criticism. In Greek religion and mythology, Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, hunting, and rustic music, and companion of the nymphs. His name originates within the Ancient Greek language, from the word paein (πάειν), meaning “to pasture.” He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr. With his homeland in rustic Arcadia, he is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, and wooded glens; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring. The ancient Greeks also considered Pan to be the god of theatrical criticism.

In Roman religion and myth, Pan’s counterpart was Faunus, a nature god who was the father of Bona Dea, sometimes identified as Fauna; he was also closely associated with Sylvanus, due to their similar relationships with woodlands. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Pan became a significant figure in the Romantic movement of western Europe and also in the 20th-century Neopagan movement.

An area in the Golan Heights known as the Panion or Panium is associated with Pan. The city of Caesarea Philippi, the site of the Battle of Panium and the Banias natural spring, grotto or casve, and related shrines dedicated to Pan, may be found there.

Antigonus II Gonatas (c. 319-239 BC) was a powerful ruler who solidified the position of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedon after a long period defined by anarchy and chaos and acquired fame for his victory over the Gauls who had invaded the Balkans.

Birth and family

Antigonus Gonatas was born around 319 BC, probably in Gonnoi in Thessaly unless Gonatas is derived from an iron plate protecting the knee (Ancient Greek gonu, genitive gonatos). He was related to the most powerful of the Diadochi (the generals of Alexander who divided the empire after his death in 323 BC). Antigonus’s father was Demetrius Poliorcetes, who was the son of Antigonus I Monophthalmus, who then controlled much of Asia. His mother was Phila, the daughter of Antipater. The latter controlled Macedonia and the rest of Greece and was recognized as regent of the empire, which in theory remained united. In this year, however, Antipater died, leading to further struggles for territory and dominance.

The careers of Antigonus’s grandfather and father showed great swings in fortune. After coming closer than anyone to reuniting the empire of Alexander, Antigonus Monophthalmus was defeated and killed in the great battle of Ipsus in 301 BC and the territory he formerly controlled was divided among his enemies, Cassander, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Seleucus.

Demetrius’s general

The fate of Antigonus Gonatas, now 18, was closely tied with that of his father Demetrius, who escaped from the battle with 9,000 troops. Jealousy among the victors eventually allowed Demetrius to regain part of the power his father had lost. He conquered Athens and in 294 BC he seized the throne of Macedonia from Alexander, the son of Cassander.

Because Antigonus Gonatas was the grandson of Antipater and the nephew of Cassander through his mother, his presence helped to reconcile the supporters of these former kings to the rule of his father.

In 292 BC, while Demetrius was campaigning in Boeotia, he received news that Lysimachus, the ruler of Thrace and the enemy of his father, had been taken prisoner by Dromichaetes, a ruler of the Getae. Hoping to seize Lysimachus’s territories in Thrace and Asia, Demetrius delegated command of his forces in Boeotia to Antigonus and immediately marched north. While he was away, the Boeotians rose in rebellion, but were defeated by Antigonus, who bottled them up in Thebes.

After the failure of his expedition to Thrace, Demetrius rejoined his son at the siege of Thebes. As the Thebans defended their city stubbornly, Demetrius often forced his men to attack the city at great cost, even though there was little hope of capturing it. It is said that, distressed by the heavy losses, Antigonus asked his father: “Why, father, do we allow these lives to be thrown away so unnecessarily?” Demetrius appears to have showed his contempt for the lives of his soldiers by replying: “We don’t have to find rations for the dead.” But he also showed a similar disregard for his own life and was badly wounded at the siege by a bolt through the neck.

In 291 BC, Demetrius finally took the city after using siege engines to demolish its walls. But control of Macedonia and most of Greece was merely a stepping stone to his plans for further conquest. He aimed at nothing less than the revival of Alexander’s empire and started making preparations on a grand scale, ordering the construction of a fleet of 500 ships, many of them of unprecedented size.

Such preparations and the obvious intent behind them, naturally alarmed the other kings, Seleucus, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Pyrrhus, who immediately formed an alliance. In the spring of 288 BC Ptolemy’s fleet appeared off Greece, inciting the cities to revolt. At the same time, Lysimachus attacked Macedonia from the east while Pyrrhus did so from the west. Demetrius left Antigonus in control of Greece, while he hurried to Macedonia.

By now the Macedonians had come to resent the extravagance and arrogance of Demetrius, and were not prepared to fight a difficult campaign for him. In 287 BC, Pyrrhus took the Macedonian city of Verroia and Demetrius’s army promptly deserted and went over to the enemy who was much admired by the Macedonians for his bravery. At this change of fortune, Phila, the mother of Antigonus, killed herself with poison. Meanwhile, in Greece, Athens revolted. Demetrius therefore returned and besieged the city, but he soon grew impatient and decided on a more dramatic course. Leaving Antigonus in charge of the war in Greece, he assembled all his ships and embarked with 11,000 infantry and all his cavalry to attack Caria and Lydia, provinces of Lysimachus.

By separating himself from his son and departing into Asia, Demetrius seemed to take his bad luck with him, but in reality it was the fear and the jealousy of the other kings. As Demetrius was chased across Asia Minor to the Taurus Mountains by the armies of Lysimachus and Seleucus, Antigonus attained success in Greece. Ptolemy’s fleet was driven off and Athens surrendered.

In the wilderness

In 285 BC, Demetrius, worn down by his fruitless campaign, surrendered to Seleucus. At this point, he wrote to his son and to his commanders in Athens and Corinth telling them to henceforth consider him a dead man and to ignore any letters they might receive written under his seal. Macedonia, meanwhile, had been divided between Pyrrhus and Lysimachus, but like two wolves sharing a piece of meat, they soon fought over it with the result that Lysimachus drove Pyrrhus out and took over the whole kingdom.

Following the capture of his father, Antigonus proved himself a dutiful son. He wrote to all the kings, especially Seleucus, offering to surrender all the territory he controlled and proposing himself as a hostage for his father’s release, but to no avail. In 283 BC, at the age of 55, Demetrius died in captivity in Syria. When Antigonus heard that his father’s remains were being brought to him, he put to sea with his entire fleet, met Seleucus’s ships near the Cyclades, and took the relics to Corinth with great ceremony. After this, the remains were interred at the town of Demetrias that his father had founded in Thessaly.

In 282 BC, Seleucus declared war on Lysimachus and the next year defeated and killed him at the Battle of Corupedium in Lydia. He then crossed to Europe to claim Thrace and Macedonia, but Ptolemy Keraunos, the son of Ptolemy, murdered Seleucus and seized the Macedonian throne. Antigonus decided the time was ripe to take back his father’s kingdom, but when he marched north, Ptolemy Ceraunus defeated his army.

Ptolemy’s success, however, was short-lived. In the winter of 279 BC, a great horde of Gauls under their leader Brennus descended on Macedonia from the northern forests, crushed Ptolemy’s army and killed him in battle, starting two years of complete anarchy in the kingdom. After plundering Macedonia, the Gauls invaded further regions of Greece, moving southwards. Antigonus cooperated in the defence of Greece against the barbarians, but the Aetolians took the lead in defeating the Gauls. In 278 BC a Greek army with a large Aetolian contingent checked the Gauls at Thermopylae and Delphi, inflicting heavy casualties and forcing them to retreat.

The next year (277 BC), Antigonus sailed to the Hellespont, landing near Lysimachia at the neck of the Thracian Chersonese. When an army of Gauls under the command of Cerethrius appeared, Antigonus laid an ambush. He abandoned his camp and beached his ships, then concealed his men. The Gauls looted the camp, but when they started to attack the ships, Antigonus’s army appeared, trapping them with the sea to their rear. In this way Antigonus resoundingly won the Battle of Lysimachia and claimed the Macedonian throne. Around this time, under these favorable omens, Antigonus’s niece-wife Phila gave birth to his son and successor, Demetrius II Aetolicus.

King of Macedonia

Antigonus against Pyrrhus

Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, Macedonia’s western neighbour, was a general of mercurial ability, widely renowned for his bravery, but he did not apply his talents sensibly and often snatched after vain hopes, so that Antigonus used to compare him to a dice player, who had excellent throws, but did not know how to use them. When the Gauls defeated Ptolemy Ceraunus and the Macedonian throne became vacant, Pyrrhus was occupied in his campaigns overseas. Hoping to conquer first Italy and then Africa, he got involved in wars against Rome and Carthage, the two most powerful states in the western Mediterranean. He then lost the support of the Greek cities in Italy and Sicily by his haughty behaviour. Needing reinforcements, he wrote to Antigonus as a fellow Greek king, asking him for troops and money, but Antigonus politely refused. In 275 BC, the Romans fought Pyrrhus at the Battle of Beneventum which ended inconclusively, although many modern sources wrongly state that Pyrrhus lost the battle. Pyrrhus had been drained by his recent wars in Sicily, and by the earlier “Pyrrhic victoriess” over the Romans, and thus decided to end his campaign in Italy and return to Epirus.

Pyrrhus’s retreat from Italy, however, proved very unlucky for Antigonus. Returning to Epirus with an army of eight thousand foot and five hundred horse, he was in need of money to pay them. This encouraged him to look for another war, so the next year, after adding a force of Gallic mercenaries to his army, he invaded Macedonia with the intention of filling his coffers with plunder. The campaign, however, went better than expected. Making himself master of several towns and being joined by two thousand deserters, his hopes started to grow and he went in search of Antigonus, attacking his army in a narrow pass and throwing it into disorder at the Battle of the Aoos River. Antigonus’s Macedonian troops retreated, but his own body of Gallic mercenaries, who had charge of his elephants, stood firm until Pyrrhus’s troops surrounded them, whereupon they surrendered both themselves and the elephants. Pyrrhus now chased after the rest of Antigonus’s army which, demoralised by its earlier defeat, declined to fight. As the two armies faced each other, Pyrrhus called out to the various officers by name and persuaded the whole body of infantry to desert. Antigonus escaped by concealing his identity. Pyrrhus now took control of upper Macedonia and Thessaly, while Antigonus held on to the coastal towns.

But Pyrrhus now wasted his victory. Taking possession of Aegae, the ancient capital of Macedonia, he installed a garrison of Gauls, who greatly offended the Macedonians by digging up the tombs of their kings and leaving the bones scattered about as they searched for gold. He also neglected to finish off his enemy. Leaving him in control of the coastal cities, he contented himself with insults. He called Antigonus a shameless man for still wearing the purple, but he did little to destroy the remnants of his power.

Before this campaign was finished, Pyrrhus had embarked upon a new one. In 272 BC, Cleonymus, an important Spartan, invited him to invade Laconia. Gathering an army of twenty-five thousand foot, two thousand horse, and twenty-four elephants, he crossed over to the Peloponnese and occupied Megalopolis in Arcadia. Antigonus, after reoccupying part of Macedonia, gathered what forces he could and sailed to Greece to oppose him. As a large part of the Spartan army led by king Areus was in Crete at the time, Pyrrhus besieged Sparta with great hopes of taking the city easily, but the citizens organized stout resistance, allowing one of Antigonus’s commanders, Aminias, the Phocian, to reach the city with a force of mercenaries from Corinth. Soon after this, the Spartan king, Areus, returned from Crete with 2,000 men. These reinforcements stiffened resistance, and Pyrrhus, finding that he was losing men to desertion every day, broke off the attack and started to plunder the country.

The most important Peloponnesian city after Sparta was Argos. The two chief men, Aristippus and Aristeas, were keen rivals. As Aristippus was an ally of Antigonus, Aristeas invited Pyrrhus to come to Argos to help him take over the city. Antigonus, aware that Pyrrhus was advancing on Argos, marched his army there as well, taking up a strong position on some high ground near the city. When Pyrrhus learned this, he encamped about Nauplia and the next day dispatched a herald to Antigonus, calling him a coward and challenging him to come down and fight on the plain. Antigonus replied that he would choose his own moment to fight and that if Pyrrhus was weary of life, he could find many ways to die.

The Argives, fearing that their territory would become a war zone, sent deputations to the two kings begging them to go elsewhere and allow their city to remain neutral. Both kings agreed, but Antigonus won over the trust of the Argives by surrendering his son as a hostage for his pledge. Pyrrhus, who had recently lost a son in the retreat from Sparta, did not. Indeed, with the help of Aristeas, he was plotting to seize the city. In the middle of the night, he marched his army up to the city walls and entered through a gate that Aristeas had opened. His Gallic troops seized the market place, but he had difficulty getting his elephants into the city through the small gates. This gave the Argives time to rally. They occupied strong points and sent messengers asking Antigonus for help.

When Antigonus heard that Pyrrhus had treacherously attacked the city, he advanced to the walls and sent a strong force inside to help the Argives. At the same time Areus arrived with a force of 1,000 Cretans and light-armed Spartans. These forces attacked the Gauls in the market place. Pyrrhus, realising that his Gallic troops were hard pressed, now advanced into the city with more troops, but in the narrow streets this soon led to confusion as men got lost and wandered around. The two forces now paused and waited for daylight. When the sun rose, Pyrrhus saw how strong the opposition was and decided the best thing was to retreat. Fearing that the gates would be too narrow for his troops to easily exit the city, he sent a message to his son, Helenus, who was outside with the main body of the army, asking him to break down a section of the walls. The messenger, however, failed to convey his instructions clearly. Misunderstanding what was required, Helenus took the rest of the elephants and some picked troops and advanced into the city to help his father.

With some of his troops trying to get out of the city and others trying to get in, Pyrrhus’s army was now thrown into confusion. This was made worse by the elephants. The largest one had fallen across the gateway and was blocking the way, while another elephant, called Nicon, was trying to find its rider. This beast surged against the tide of fugitives, crushing friend and foe alike, until it found its dead master, whereupon it picked him up, placed him on its tusks, and went on the rampage. In this chaos Pyrrhus was struck down by a tile thrown by an old woman and killed by Zopyrus, a soldier of Antigonus. Thus ended the career of the most famous soldier of his time.

Alcyoneus, one of Antigonus’s sons, heard that Pyrrhus had been killed. Taking the head, which had been cut off by Zopyrus, he rode to where his father was and threw it at his feet. Far from being delighted, Antigonus was angry with his son and struck him, calling him a barbarian and drove him away. He then covered his face with his cloak and burst into tears. The fate of Pyrrhus reminded him all too clearly of the tragic fates of his own grandfather and his father who had suffered similar swings of fortune. He then had Pyrrhus’s body cremated with great ceremony.

After the death of Pyrrhus, his whole army and camp surrendered to Antigonus, greatly increasing his power. Later, Alcyoneus discovered Helenus, Pyrrhus’s son, disguised in threadbare clothes. He treated him kindly and brought him to his father who was more pleased with his behaviour. “This is better than what you did before, my son,” he said, “but why leave him in these clothes which are a disgrace to us now that we know ourselves the victors?” Greeting him courteously, Antigonus treated Helenus as an honored guest and sent him back to Epirus.

This was not the end of Antigonus’ problems with Epirus: shortly after Alexander II, the son of Pyrrhus and his successor as king of Epirus, repeated his father’s adventure by conquering Macedonia. However, only a few years later, Alexander was not only expelled from Macedonia by Antigonus’ son Demetrius, but he also lost Epirus and had to go into exile in Acarnania. His exile didn’t last long, as the Macedonians had to abandon Epirus eventually under pressure from Alexander’s allies, the Acarnanians and the Aetolians. Alexander seems to have died about 242 BC, leaving his country under the regency of his wife Olympias who proved anxious to have good relations with Epirus’ powerful neighbour, as was sanctioned by the marriage between the regent’s daughter Phthia and Antigonus’ son and heir Demetrius.

Chremonidean War

With the restoration of the territories captured by Pyrrhus, and with grateful allies in Sparta and Argos, and garrisons in Corinth and other cities, Antigonus securely controlled Macedonia and Greece. The careful way he guarded his power shows that he wished to avoid the vicissitudes of fortune that had characterized the careers of his father and grandfather. Aware that the Greeks loved freedom and autonomy, he was careful to grant a semblance of this in as much as it did not clash with his own power. Also, he tried to avoid the odium that direct rule brings by controlling the Greeks through intermediaries. It is for this reason that Polybius says, “No man ever set up more absolute rulers in Greece than Antigonus.” The tyrants installed or maintained by Gonatas include: Cleon (Sicyon, c. 300-280 BC), Euthydemus and Timocleidas (Sicyon c. 280-270 BC), Iseas (Keryneia, resigned 275 BC), Aristotimus (Elis, assassinated 272 BC), Aristippus the Elder (Argos, from 272 BC), Abantidas (Sicyon, 264-252 BC), Aristodemus the Good (Megalopolis, assassinated 252 BC), Paseas (Sicyon, 252-251 BC), Nicocles (Sicyon, 251 BC), Aristomachus (Argos, assassinated 240 BC), Lydiadas, (Megalopolis, c. 245-235 BC), and Aristippus (Argos, 240-235 BC).

The next stage of Antigonus’s career is not documented and what we know has been patched together from a few historical fragments: Antigonus seems to have been on very good terms with Antiochus, the Seleucid ruler of Asia, whose love for Stratonice, the sister of Antigonus, is very famous. Such an alliance naturally threatened the third successor state, Ptolemaic Egypt. In Greece, Athens and Sparta, once the dominant states, naturally resented the domination of Antigonus. The pride, which in the past had made these cities mortal enemies, now served to unite them. In 267 BC, probably with encouragement from Egypt, an Athenian by the name of Chremonides persuaded the Athenians to join the Spartans in declaring war on Antigonus (see Chremonidean War).

The Macedonian king responded by ravaging the territory of Athens with an army while blockading them by sea. In this campaign he also destroyed the grove and temple of Poseidon that stood at the entrance to Attica near the border with Megara. To support the Athenians and prevent the power of Antigonus from growing too much, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the king of Egypt, sent a fleet to break the blockade. The Egyptian admiral, Patroclus, landed on a small uninhabited island near Laurium and fortified it as a base for naval operations.

The Seleucid Empire had signed a peace treaty with Egypt, but Antiochus’s son-in-law, Magas, king of Cyrene, persuaded Antiochus to take advantage of the war in Greece to attack Egypt. To counter this, Ptolemy dispatched a force of pirates and freebooters to raid and attack the lands and provinces of Antiochus, while his army fought a defensive campaign, holding back the stronger Seleucid army. Although successfully defending Egypt, Ptolemy II was unable to save Athens from Antigonus. In 263/2 or 262/1 BC, the Athenians and Spartans, worn down by several years of war and the devastation of their lands, made peace with Antigonus, who thus retained his hold on Greece.

Ptolemy II continued to interfere in the affairs of Greece and this led to war in 261. After two years in which little changed, Antiochus II, the new Seleucid king, made a military agreement with Antigonus, and the Second Syrian War began. Under the combined attack, Egypt lost ground in Anatolia and Phoenicia, and the city of Miletus, held by its ally, Timarchus, was seized by Antiochus II Theos. In 255 BC, Ptolemy made peace, ceding lands to the Seleucids and confirming Antigonus in his mastery of Greece.

Two years later, however, the Egyptian interfered again, inducing with his subsidies the Macedonian governor of Corinth and Euboea, Alexander, son of Craterus, to challenge his king, seeking independence as a tyrant. Alexander’s revolt was the most serious threat to the Macedonian hegemony in Greece, and since Antigonus’ military efforts were unsuccessful, he probably resolved to poison the traitor in 247 BC. By offering a marriage with his heir Demetrius II Aetolicus Antigonus took in his widow Nicaea and regained control of Corinth in the winter of 245/44 BC.

Antigonus against Aratus

Having successfully repelled the external threat to his control of Greece, the main danger to the power of Antigonus lay in the Greek love of liberty. In 251 BC, Aratus, a young nobleman in the city of Sicyon, expelled the tyrant Nicocles, who had ruled with the acquiescence of Antigonus, freed the people, and recalled the exiles. This led to confusion and division within the city. Fearing that Antigonus would exploit these divisions to attack the city, Aratus applied for the city to join the Achaean League, a league of a few small Achaean towns in the Pelopennese.

Preferring to use guile rather than military power, Antigonus sought to regain control over Sicyon through winning the young man over to his side. Accordingly, he sent him a gift of 25 talents, but, Aratus, instead of being corrupted by this wealth, immediately gave it away to his fellow citizens. With this money and another sum he received from Ptolemy II Philadelphus, he was able to reconcile the different parties in Sicyon and unite the city.

Antigonus was troubled by the rising power and popularity of Aratus. If he were to receive extensive military and financial support from Ptolemy, Aratus would be able to threaten his position. He decided therefore to either win him over to his side or at least discredit him with Ptolemy. In order to do this, he showed him great marks of favour. When he was sacrificing to the gods in Corinth, he sent portions of the meat to Aratus at Sicyon, and complimented Aratus in front of his guests: “I thought this Sicyonian youth was only a lover of liberty and of his fellow-citizens, but now I look upon him as a good judge of the manners and actions of kings. For formerly he despised us, and, placing his hopes further off, admired the Egyptians, hearing much of their elephants, fleets, and palaces. But after seeing all these at a nearer distance, and perceiving them to be but mere stage props and pageantry, he has now come over to us. And for my part I willingly receive him, and, resolving to make great use of him myself, command you to look upon him as a friend.” These words were readily believed by many, and when they were reported to Ptolemy, he half believed them.

But Aratus was far from becoming a friend of Antigonus, whom he regarded as the oppressor of his city’s freedom. In 243 BC, in an attack by night, he seized the Acrocorinth, the strategically important fort by which Antigonus controlled the Isthmus and thus the Pelopennese. When news of this success reached Corinth, the Corinthians rose in rebellion, overthrew Antigonus’ party, and joined the Achaean League. Next Aratus took the port of Lechaeum and captured 25 of Antigonus’s ships.

This setback for Antigonus sparked a general uprising against Macedonian power. The Megarians revolted and together with the Troezenians and Epidaurians enrolled in the Achaean League. With this increased strength, Aratus invaded the territory of Athens and plundered Salamis. Every Athenian freeman he captured was sent back to the Athenians without ransom to encourage them to join the rebellion. The Macedonians, however, retained their hold on Athens and the rest of Greece.

Relations with India

Antigonus is mentioned in the Edicts of Ashoka as one of the recipients of the Indian Emperor Ashoka’s Buddhist proselytism.

Relationship with Philosophers

Antigonus surrounded himself at court with a circle of notable intellectuals and philosophers. He was mentioned several times by Diogenes Laertius in The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, in relation to various philosophers, particularly those linked with the closely related Megarian, Cynic, and Stoic schools. We’re told that “many persons courted Antigonus and went to meet him whenever he came to Athens” and that after an unnamed sea battle, many Athenians went to see Antigonus or wrote him flattering letters.

Many of the philosophers linked with Antigonus were associated with the Megarian school. Euphantus, a philosopher of the Megarian school, taught King Antigonus “and dedicated to him a work On Kingship which was very popular”. We’re also told that Antigonus consulted Menedemus of Eretria, a distinguished member of Phaedo’s school of philosophy, about whether to attend a drinking party. Antigonus also knew the Skeptic philosopher Timon of Phlius. Menedemus and Timon were both associated with the Megarian school. When the eclectic philosopher Bion of Borysthenes, who was best known as resembling the Cynics, fell ill, Antigonus sent two servants to act as nurses to him, and Antigonus himself reputedly later visited him.

Ultimately, though, Antigonus became most associated with the Stoics. Zeno of Citium studied under both the Megarians and Cynics before founding the Stoic school and he became particularly associated with Antigonus. We’re told “Antigonus (Gonatas) also favoured him [Zeno], and whenever he came to Athens would hear him lecture and often invited him to come to his court.”. Diogenes Laertius reproduces a brief series of letters between Zeno and Antigonus, in which he asked the Stoic to attend his court and help guide him in virtue, for the benefit of the Macedonian people. Zeno at this time was too sickly and frail to travel so instead he sent two of his best students Persaeus and Philonides the Theban, who subsequently lived with Antigonus. After Zeno’s death, Antigonus reputedly exclaimed “What an audience I have lost!”. Antigonus subsequently made a gift of three thousand drachmas to Cleanthes, Zeno’s successor as head of the Stoa, whose lectures he also attended. The poet Aratus, who had also studied Stoicism under Zeno, lived at the court of Antigonus.

Death and appraisal

In 239 BC, Antigonus died at the age of 80 and left his kingdom to his son Demetrius II, who was to reign for the next 10 years. Except for a short period when he defeated the Gauls, Antigonus was not a heroic or successful military leader. His skills were mainly political. He preferred to rely on cunning, patience, and persistence to achieve his goals. While more brilliant leaders, like his father Demetrius and his neighbour Pyrrhus, aimed higher and fell lower, Antigonus achieved a measure of security. It is also said of him that he gained the affection of his subjects by his honesty and his cultivation of the arts, which he accomplished by gathering round him distinguished literary men, in particular philosophers, poets, and historians. A tomb in Vergina is suggested to be his own.

|

Athena or Athene (Latin: Minerva), also referred to as Pallas Athena, is the goddess of war, civilization, wisdom, strength, strategy, crafts, justice and skill in Greek mythology. Minerva, Athena’s Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is also a shrewd companion of heroes and the goddess of heroic endeavour. She is the virgin patron of Athens. The Athenians built the Parthenon on the Acropolis of her namesake city, Athens, in her honour (Athena Parthenos). Athena’s cult as the patron of Athens seems to have existed from the earliest times and was so persistent that archaic myths about her were recast to adapt to cultural changes. In her role as a protector of the city (polis), many people throughout the Greek world worshiped Athena as Athena Polias (“Athena of the city”). Athens and Athena bear etymologically connected names.

Athena or Athene (Latin: Minerva), also referred to as Pallas Athena, is the goddess of war, civilization, wisdom, strength, strategy, crafts, justice and skill in Greek mythology. Minerva, Athena’s Roman incarnation, embodies similar attributes. Athena is also a shrewd companion of heroes and the goddess of heroic endeavour. She is the virgin patron of Athens. The Athenians built the Parthenon on the Acropolis of her namesake city, Athens, in her honour (Athena Parthenos). Athena’s cult as the patron of Athens seems to have existed from the earliest times and was so persistent that archaic myths about her were recast to adapt to cultural changes. In her role as a protector of the city (polis), many people throughout the Greek world worshiped Athena as Athena Polias (“Athena of the city”). Athens and Athena bear etymologically connected names. In Greek religion and mythology, Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, hunting, and rustic music, and companion of the nymphs. His name originates within the Ancient Greek language, from the word paein (πάειν), meaning “to pasture.” He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr. With his homeland in rustic Arcadia, he is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, and wooded glens; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring. The ancient Greeks also considered Pan to be the god of theatrical criticism.

In Greek religion and mythology, Pan is the god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, hunting, and rustic music, and companion of the nymphs. His name originates within the Ancient Greek language, from the word paein (πάειν), meaning “to pasture.” He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a faun or satyr. With his homeland in rustic Arcadia, he is also recognized as the god of fields, groves, and wooded glens; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the season of spring. The ancient Greeks also considered Pan to be the god of theatrical criticism.