|

Antigonos II Gonatas

– Macedonian King: 277-239

B.C. –

Bronze 19mm (6.14 grams) Struck 277-239 B.C.

Reference: Sear 6786; Price, pl. XII, 71; SNGCop 1209

Head of Athena right, in crested Corinthian helmet.

Pan

advancing right, erecting trophy; B-A in upper field; ANTI monogram beneath

Pan.

The god Pan is said to have intervened on behalf of the

Macedonians in Antiogonos’ battle

with the Gauls in 277 B.C.

Son of Demetrios Poliorketes,

Antigonos Gonatas claimed his father’s throne after achieving a notable victory

over the Gallic invaders in Thrace. The Macedonian kingdom prospered again under

his long and enlightened rule.

A trophy is a reward for a specific achievement, and serves as

recognition or evidence of merit.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

In

Greek religion

and

mythology

, Pan (Ancient

Greek: Πᾶν, Pān) is the

god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, hunting and

rustic music

, and companion of the

nymphs

.[1]

His name originates within the

Ancient Greek

language, from the word paein

(πάειν), meaning “to pasture.”[2]

He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a

faun or satyr

. With his homeland in rustic

Arcadia

, he is recognized as the god of fields,

groves, and wooded glens; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the

season of spring. The ancient Greeks also considered Pan to be the god of

theatrical criticism.

The god Pan is said to have intervened on behalf of the

Macedonians in Antiogonos’ battle

with the Gauls in 277 B.C.

In

Roman religion and myth

, Pan’s counterpart was

Faunus

, a nature god who was the father of

Bona Dea

, sometimes identified as

Fauna

. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Pan

became a significant figure in

the Romantic movement

of western Europe, and

also in the 20th-century

Neopagan movement

.

Origins

In his earliest appearance in literature,

Pindar

‘s Pythian Ode iii. 78, Pan is associated

with a

mother goddess

, perhaps

Rhea

or

Cybele

; Pindar refers to virgins worshipping

Cybele

and Pan near the poet’s house in

Boeotia

.

The parentage of Pan is unclear; in some

myths

he is the son of

Zeus, though generally he is the son of

Hermes

or

Dionysus

, with whom his mother is said to be a

nymph

, sometimes

Dryope

or, in

Nonnus

, Dionysiaca (14.92), Penelope of

Mantineia

in Arcadia. This nymph at some point

in the tradition became conflated with

Penelope

, the wife of

Odysseus

.

Pausanias

8.12.5 records the story that

Penelope had in fact been unfaithful to her husband, who banished her to

Mantineia upon his return. Other sources (Duris

of Samos; the Vergilian commentator

Servius

) report that Penelope slept with all

108 suitors in Odysseus’ absence, and gave birth to Pan as a result. This myth

reflects the folk etymology that equates Pan’s name (Πάν) with the Greek word

for “all” (πᾶν). It is more likely to be

cognate

with paein, “to pasture”, and to

share an origin with the modern English word “pasture”. In 1924, Hermann Collitz

suggested that Greek Pan and Indic

Pushan

might have a common Indo-European

origin. In the

Mystery cults

of the highly syncretic

Hellenistic

era Pan is made cognate with

Phanes/Protogonos

,

Zeus,

Dionysus

and

Eros

.

The

Roman

Faunus

, a god of Indo-European origin, was

equated with Pan. However, accounts of Pan’s genealogy are so varied that it

must lie buried deep in mythic time. Like other nature spirits, Pan appears to

be older than the

Olympians

, if it is true that he gave

Artemis

her hunting dogs and taught the secret

of prophecy to Apollo

. Pan might be multiplied as the Panes

(Burkert 1985, III.3.2; Ruck and Staples 1994 p 132) or the Paniskoi.

Kerenyi (p. 174) notes from

scholia

that

Aeschylus

in Rhesus distinguished

between two Pans, one the son of Zeus and twin of

Arcas

, and one a son of

Cronus

. “In the retinue of

Dionysos

, or in depictions of wild landscapes,

there appeared not only a great Pan, but also little Pans, Paniskoi, who played

the same part as the Satyrs

“.

Worship

The worship of Pan began in

Arcadia

which was always the principal seat of

his worship. Arcadia was a district of mountain people whom other Greeks

disdained. Greek hunters used to scourge the statue of the god if they had been

disappointed in the chase (Theocritus. vii. 107). Being a rustic god, Pan was

not worshipped in temples or other built edifices, but in natural settings,

usually caves

or

grottoes

such as the one on the north slope of

the

Acropolis of Athens

. These are often referred

to as the Cave of Pan

. The only exceptions are the

Temple of Pan

on the

Neda River

gorge in the southwestern

Peloponnese

– the ruins of which survive to

this day – and the Temple of Pan at

Apollonopolis Magna in

ancient Egypt

.

Mythology

Greek deities

series |

|

Primordial deities

|

Titans

and

Olympians

|

|

Aquatic deities

|

|

Chthonic deities

|

|

Personified concepts

|

| Other deities |

- Anemoi

-

Asclepius

-

Iris

- Leto

|

|

The goat-god Aegipan

was nurtured by

Amalthea

with the infant

Zeus in Athens. In Zeus’ battle with

Gaia

, Aegipan and

Hermes

stole back Zeus’ “sinews” that

Typhon

had hidden away in the

Corycian Cave

. Pan aided his foster-brother in

the battle with the Titans

by letting out a

horrible screech and scattering them in terror. According to some traditions,

Aegipan

was the son of Pan, rather than his

father.

One of the famous myths of Pan involves the origin of his

pan flute

, fashioned from lengths of hollow

reed. Syrinx

was a lovely water-nymph

of Arcadia, daughter of Landon, the river-god. As she was returning from the

hunt one day, Pan met her. To escape from his importunities, the fair nymph ran

away and didn’t stop to hear his compliments. He pursued from Mount Lycaeum

until she came to her sisters who immediately changed her into a reed. When the

air blew through the reeds, it produced a plaintive melody. The god, still

infatuated, took some of the reeds, because he could not identify which reed she

became, and cut seven pieces (or according to some versions, nine), joined them

side by side in gradually decreasing lengths, and formed the musical instrument

bearing the name of his beloved

Syrinx

. Henceforth Pan was seldom seen without

it.

Echo

was a nymph who was a great singer and

dancer and scorned the love of any man. This angered Pan, a

lecherous god, and he instructed his followers to kill her. Echo was

torn to pieces and spread all over earth. The goddess of the earth,

Gaia

, received the pieces of Echo, whose voice

remains repeating the last words of others. In some versions, Echo and Pan had

two children: Iambe

and

Iynx. In other versions, Pan had fallen in love with Echo, but she

scorned the love of any man but was enraptured by Narcissus. As Echo was cursed

by Hera to only be able to repeat words that had been said by someone else, she

could not speak for herself. She followed Narcissus to a pool, where he fell in

love with his own reflection and changed into a narcissus flower. Echo wasted

away, but her voice could still be heard in caves and other such similar places.

Pan also loved a nymph named

Pitys

, who was turned into a pine tree to

escape him.

Disturbed in his secluded afternoon naps, Pan’s angry shout inspired

panic

(panikon deima) in lonely

placesFollowing the Titans’ assault on

Olympus

, Pan claimed credit for the victory of

the gods because he had frightened the attackers. In the

Battle of Marathon

(490 BC), it is said that

Pan favored the Athenians and so inspired panic in the hearts of their enemies,

the Persians

Erotic aspects

Pan with a goat, statue from

Villa of the Papyri

,

Herculaneum

.

Pan is famous for his sexual powers, and is often depicted with a

phallus

.

Diogenes of Sinope

, speaking in jest, related a

myth of Pan learning

masturbation

from his father,

Hermes

, and teaching the habit to shepherds.

Pan’s greatest conquest was that of the moon goddess

Selene

. He accomplished this by wrapping

himself in a

sheepskin

to hide his hairy black goat form,

and drew her down from the sky into the forest where he seduced her.

Pan and music

In two late Roman sources,

Hyginus

and

Ovid, Pan is substituted for the satyr

Marsyas

in the theme of a musical competition (agon),

and the punishment by flaying is omitted.

Pan once had the audacity to compare his music with that of

Apollo

, and to challenge Apollo, the god of the

lyre, to a trial of skill.

Tmolus

, the mountain-god, was chosen to umpire.

Pan blew on his pipes and gave great satisfaction with his rustic melody to

himself and to his faithful follower,

Midas

, who happened to be present. Then Apollo

struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo,

and all but Midas agreed with the judgment. Midas dissented and questioned the

justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any

longer and turned Midas’ ears into those of a

donkey

.

In another version of the myth, the first round of the contest was a tie, so

the competitors were forced to hold a second round. In this round, Apollo

demanded that they play their instruments upside-down. Apollo, playing the lyre,

was unaffected. However, Pan’s pipe could not be played while upside down, so

Apollo won the contest.

Capricornus

The

constellation

Capricornus

is traditionally depicted as a

sea-goat, a goat with a fish’s tail (see

“Goatlike” Aigaion called Briareos, one of the

Hecatonchires

). A myth reported as “Egyptian” in

Gaius Julius Hyginus

‘ Poetic Astronomy[22]

that would seem to be invented to justify a connection of Pan with Capricorn

says that when Aegipan

— that is Pan in his goat-god aspect —

was attacked by the monster

Typhon

, he dove into the Nile; the parts above

the water remained a goat, but those under the water transformed into a fish.

Epithets

Aegocerus “goat-horned” was an epithet of Pan descriptive of his

figure with the horns of a goat.

All of the Pans

Pan could be multiplied into a swarm of Pans, and even be given individual

names, as in Nonnus

‘

Dionysiaca

, where the god Pan had twelve

sons that helped Dionysus in his war against the Indians. Their names were

Kelaineus, Argennon, Aigikoros, Eugeneios, Omester, Daphoineus, Phobos,

Philamnos, Xanthos, Glaukos, Argos, and Phorbas.

Two other Pans were

Agreus

and

Nomios

. Both were the sons of Hermes, Agreus’

mother being the nymph Sose, a prophetess: he inherited his mother’s gift of

prophecy, and was also a skilled hunter. Nomios’ mother was Penelope (not the

same as the wife of Odysseus). He was an excellent shepherd, seducer of nymphs,

and musician upon the shepherd’s pipes. Most of the mythological stories about

Pan are actually about Nomios, not the god Pan. Although, Agreus and Nomios

could have been two different aspects of the prime Pan, reflecting his dual

nature as both a wise prophet and a lustful beast.

Aegipan

, literally “goat-Pan,” was a Pan who

was fully goatlike, rather than half-goat and half-man. When the Olympians fled

from the monstrous giant Typhoeus and hid themselves in animal form, Aegipan

assumed the form of a fish-tailed goat. Later he came to the aid of Zeus in his

battle with Typhoeus, by stealing back Zeus’ stolen sinews. As a reward the king

of the gods placed him amongst the stars as the Constellation Capricorn. The

mother of Aegipan, Aix (the goat), was perhaps associated with the constellation

Capra.

Sybarios was an Italian Pan who was worshipped in the Greek colony of Sybaris

in Italy. The Sybarite Pan was conceived when a Sybarite shepherd boy named

Krathis copulated with a pretty she-goat amongst his herds.

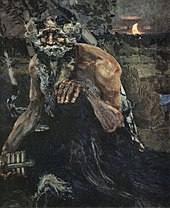

The “Death” of Pan

Pan,

Mikhail Vrubel

1900.

According to the Greek historian

Plutarch

(in De defectu oraculorum, “The

Obsolescence of Oracles”), Pan is the only Greek god (other than

Asclepius

) who actually dies. During the reign

of Tiberius

(A.D. 14–37), the news of Pan’s death

came to one Thamus, a sailor on his way to Italy by way of the island of

Paxi. A divine voice hailed him across the salt water, “Thamus, are

you there? When you reach

Palodes

, take care to proclaim that the great

god Pan is dead.” Which Thamus did, and the news was greeted from shore with

groans and laments.

Christian apologists took Plutarch’s notice to heart, and repeated and

amplified it until the 18th century. It was interpreted with

concurrent meanings

exegesisin all four modes of medieval

: literally as historical fact, and

allegorically

as the death of the ancient order

at the coming of the new.[original

research?]

Eusebius of Caesarea

in his

Praeparatio Evangelica

(book V) seems to

have been the first Christian apologist to give Plutarch’s anecdote, which he

identifies as his source pseudo-historical standing, which Eusebius buttressed

with many invented passing details that lent

verisimilitude

. It should be noted that it

would be absurd for medieval Christian apologists to even consider Plutarch’s

account to be historically factual–and not merely a symbolic anecdote–inasmuch

as their Christian monotheistic beliefs would inevitably come into conflict with

Plutarch’s pagan polytheistic account.

In more modern times, some have suggested a possible a naturalistic explanation

for the myth. For example,

Robert Graves

(The Greek Myths) reported

a suggestion that had been made by Salomon Reinach and expanded by James S. Van

Teslaar[29]

that the hearers aboard the ship, including a supposed Egyptian, Thamus,

apparently misheard Thamus Panmegas tethneke ‘the all-great

Tammuz

is dead’ for ‘Thamus, Great Pan is

dead!’, Thamous, Pan ho megas tethneke. “In its true form the phrase

would have probably carried no meaning to those on board who must have been

unfamiliar with the worship of Tammuz which was a transplanted, and for those

parts, therefore, an exotic custom.” Certainly, when

Pausanias

toured Greece about a century after

Plutarch, he found Pan’s shrines, sacred caves and sacred mountains still very

much frequented. However, a naturalistic explanation might not be needed. For

example, William Hansen has shown that the story is quite similar to a class of

widely-known tales known as Fairies Send a Message.

The cry “Great Pan is dead” has appealed to poets, such as

John Milton

, in his ecstatic celebration of

Christian peace,

On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity

line

89, and

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

.

One remarkable commentary of Herodotus on Pan is that he lived 800 years

before himself (c. 1200 BCE), this being already after the Trojan War.

Influence

Revivalist imagery

The Magic of Pan’s Flute, by

John Reinhard Weguelin

(1905)

In the late 18th century, interest in Pan revived among liberal scholars.

Richard Payne Knight

discussed Pan in his

Discourse on the Worship of Priapus (1786) as a symbol of creation expressed

through sexuality. “Pan is represented pouring water upon the organ of

generation; that is, invigorating the active creative power by the prolific

element.”

In the English town of

Painswick

in

Gloucestershire

, a group of 18th century

gentry, led by Benjamin Hyett, organised an annual procession dedicated to Pan,

during which a statue of the deity was held aloft, and people shouted ‘Highgates!

Highgates!” Hyett also erected temples and follies to Pan in the gardens of his

house and a “Pan’s lodge”, located over Painswick Valley. The tradition died out

in the 1830s, but was revived in 1885 by the new vicar, W. H. Seddon, who

mistakenly believed that the festival had been ancient in origin. One of

Seddon’s successors, however, was less appreciative of the pagan festival and

put an end to it in 1950, when he had Pan’s statue buried.

John Keats

‘s

“Endymion”

opens with a festival dedicated to

Pan where a stanzaic hymn is sung in praise of him. “Keats’s account of Pan’s

activities is largely drawn from the Elizabethan poets. Douglas Bush notes, ‘The

goat-god, the tutelary divinity of shepherds, had long been allegorized on

various levels, from Christ to “Universall Nature”

(Sandys)

; here he becomes the symbol of the

romantic imagination, of supra-mortal knowledge.'”

In the late nineteenth century Pan became an increasingly common figure in

literature and art. Patricia Merivale states that between 1890 and 1926 there

was an “astonishing resurgence of interest in the Pan motif”. He appears in

poetry, in novels and children’s books, and is referenced in the name of the

character Peter Pan

. He is the eponymous “Piper at the

Gates of Dawn” in the seventh chapter of

Kenneth Grahame

‘s

The Wind in the Willows

(1908). Grahame’s

Pan, unnamed but clearly recognisable, is a powerful but secretive nature-god,

protector of animals, who casts a spell of forgetfulness on all those he helps.

He makes a brief appearance to help the Rat and Mole recover the Otter’s lost

son Portly.

Arthur Machen

‘s 1894 novella

The Great God Pan

uses the god’s name in a

simile about the whole world being revealed as it really is: “. . . seeing the

Great God Pan”. The novella is considered by many (including

Stephen King

) as being one of the greatest

horror stories ever written.

Pan entices villagers to listen to his pipes as if in a trance in

Lord Dunsany

‘s novel ‘The Blessing of Pan’

published in 1927. Although the god does not appear within the story, his energy

certainly invokes the younger folk of the village to revel in the summer

twilight, and the vicar of the village is the only person worried about the

revival of worship for the old pagan god.

Pan is also featured as a prominent character in

Tom Robbins

‘

Jitterbug Perfume

(1984).

Aeronautical engineer

and

occultist

Jack Parsons

invoked Pan before test launches

at the

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

.

Identification with

Satan

Francisco Goya

,

Witches’ Sabbath (El aquelarre),

. 1798. Oil on canvas, 44 × 31 cm. Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.

Pan’s goatish image recalls conventional

faun-like depictions of

Satan

. Although Christian use of Plutarch’s

story is of long standing[original

research?][citation

needed],

Ronald Hutton

has argued that this specific

association is modern and derives from Pan’s popularity in Victorian and

Edwardian

neopaganism

. Medieval and early modern images

of Satan tend, by contrast, to show generic semi-human monsters with horns,

wings and clawed feet.

Neopaganism

In 1933, the Egyptologist

Margaret Murray

published the book, The God

of the Witches, in which she theorised that Pan was merely one form of a

horned god

who was worshipped across Europe by

a

witch-cult

. This theory influenced the

Neopagan

notion of the Horned God, as an

archetype

of male virility and sexuality. In

Wicca

, the archetype of the Horned God is

highly important, as represented by such deities as the Celtic

Cernunnos

, Indian

Pashupati

and Greek Pan.

A modern account of several purported meetings with Pan is given by

Robert Ogilvie Crombie

in The Findhorn

Garden (Harper & Row, 1975) and The Magic Of Findhorn (Harper & Row,

1975). Crombie claimed to have met Pan many times at various locations in

Scotland, including

Edinburgh

, on the island of

Iona and at the

Findhorn Foundation

.

In classical mythology, Syrinx was a

nymph

and a follower of

Artemis

, known for her

chastity

. Pursued by the amorous Greek god

Pan

, she ran to a river’s edge and asked for

assistance from the river nymphs. In answer, she was transformed into hollow

water reeds

that made a haunting sound when the god’s

frustrated breath blew across them. Pan cut the reeds to fashion the first set

of

pan pipes

, which were thenceforth known as

syrinx. The word syringe was derived from this word.

In literature

The story of the syrinx is told in

Achilles Tatius

‘

Leukippe and Kleitophon

where the heroine

is subjected to a virginity test by entering a cave where Pan has left syrinx

pipes that will sound a melody if she passes. The story became popular among

artists and writers in the 19th century. The Victorian artist and poet

Thomas Woolner

wrote Silenus, a long

narrative poem about the myth, in which Syrinx becomes the lover of

Silenus

, but drowns when she attempts to escape

rape by Pan, as a result of the crime Pan is transmuted into a demon figure and

Silenus becomes a drunkard.

Amy Clampitt

‘s poem Syrinx refers to the

myth by relating the whispering of the reeds to the difficulties of language.

The story was used as a central theme by Aifric Mac Aodha in her poetry

collection “Gabháil Syrinx”.

Samuel R. Delany

features an instrument called

a syrynx in his classic science-fiction novel Nova.

In art

“Pan and Syrinx” by

Jean-François de Troy

The Victorian artist,

Arthur Hacker

(September 25, 1858 – November

12, 1919), depicted Syrinx in his 1892 nude. This painting in oil on canvas is

currently on display in

Manchester Art Gallery

.

Sculptor

Adolph Wolter

was commissioned in 1973 to

create a replacement for a stolen sculpture of

Syrinx

in

Indianapolis

,

Indiana

. This work was a replacement for a

similar statue by

Myra Reynolds Richards

that had been stolen.

The sculpture sits in University Park located in the city’s

Indiana World War Memorial Plaza

.

In music

Claude Debussy

wrote

“Syrinx (La Flute De Pan)”

based on Pan’s

sadness over losing his love. This piece was the first unaccompanied flute solo

of the 20th century[citation

needed], and remains a very popular addition to the

modern flautist’s repertoire. It was also transcribed for solo saxophone,

becoming a standard performance piece for saxophone too. It was used as

incidental music in the play Psyché by Gabriel Mourey.[4]

French Baroque composer Michel Pignolet de Montéclair composed “Pan et Syrinx”,

a cantata for voice & ensemble (No 4 of Second livre de cantates).

Danish composer

Carl Nielsen

composed “Pan

and Syrinx” (Pan og Syrinx), Op. 49, FS 87.

Canadian

electronic

progressive rock

band

Syrinx

took their name from the legend.

Canadian

progressive rock

band

Rush

have a movement titled “The Temples of

Syrinx” in their song “2112”

on their album

2112

. The song is about a

dystopian

futuristic society in which the arts,

particularly music, have been suppressed by the Priests of the Temples of Syrinx.

Helmeted Athena with the cista and Erichthonius in his serpent form.

Roman, first century (Louvre

Museum)

In

Greek religion

and

mythology

, Athena or Athene, also

referred to as Pallas Athena/Athene , is the goddess of wisdom, courage,

inspiration, civilization, law and justice, just warfare, mathematics, strength,

strategy, the arts, crafts, and skill.

Minerva

is the

Roman goddess

identified with

Athena.

Athena is also a shrewd companion of

heroes and is the

goddess

of heroic endeavour. She is the

virgin

patroness of

Athens

. The Athenians founded the

Parthenon

on the Acropolis of her namesake

city, Athens (Athena Parthenos), in her honour.

Athena’s veneration as the patron of Athens seems to have existed from the

earliest times, and was so persistent that archaic myths about her were recast

to adapt to cultural changes. In her role as a protector of the city (polis),

many people throughout the Greek world worshiped Athena as Athena Polias

(Ἀθηνᾶ Πολιάς “Athena of the city”). The city of

Athens

and the goddess Athena essentially bear

the same name, “Athenai” meaning “[many] Athenas”.

Patroness

Athenian

tetradrachm

representing the

goddess Athena

Athena as the goddess of philosophy became an aspect of the cult in Classical

Greece during the late 5th century B.C. She is the patroness of various crafts,

especially of weaving

, as Athena Ergane, and was

honored as such at festivals such as

Chalceia

. The metalwork of weapons also fell

under her patronage. She led battles (Athena

Promachos or the warrior maiden Athena Parthenos) as the

disciplined, strategic side of war, in contrast to her brother

Ares, the patron of violence, bloodlust and slaughter—”the raw force

of war”. Athena’s wisdom includes the cunning intelligence (metis) of

such figures as Odysseus

. Not only was this version of Athena

the opposite of Ares in combat, it was also the polar opposite of the serene

earth goddess version of the deity, Athena Polias.

Athena appears in Greek mythology as the patron and helper of many heroes,

including Odysseus

,

Jason

, and

Heracles

. In

Classical Greek

myths, she never consorts with

a lover, nor does she ever marry,earning the title Athena Parthenos. A

remnant of archaic myth depicts her as the adoptive mother of

Erechtheus

/Erichthonius

through the foiled rape by

Hephaestus

. Other variants relate that

Erichthonius, the serpent that accompanied Athena, was born to

Gaia

: when the rape failed, the semen landed on

Gaia and impregnated her. After Erechthonius was born, Gaia gave him to Athena.

Though Athena is a goddess of war strategy, she disliked fighting without

purpose and preferred to use wisdom to settle predicaments.The goddess only

encouraged fighting for a reasonable cause or to resolve conflict. As patron of

Athens she fought in the Trojan war on the side of the Achaeans.

Mythology

Lady of Athens

Athena competed with

Poseidon

to be the patron deity of Athens,

which was yet unnamed, in a version of one

founding myth

. They agreed that each would give

the Athenians one gift and that the Athenians would choose the gift they

preferred. Poseidon struck the ground with his

trident

and a salt water spring sprang up; this

gave them a means of trade and water—Athens at its height was a significant sea

power, defeating the

Persian

fleet at the

Battle of Salamis

—but the water was salty and

not very good for drinking.

Athena, however, offered them the first domesticated

olive tree

. The Athenians (or their king,

Cecrops

) accepted the olive tree and with it

the patronage of Athena, for the olive tree brought wood, oil, and food.

Robert Graves

was of the opinion that

“Poseidon’s attempts to take possession of certain cities are political myths”

which reflect the conflict between matriarchal and patriarchal religions.

Other sites of cult

Athena also was the patron goddess of several other Greek cities, notably

Sparta, where the archaic cult of

Athena Alea

had its sanctuaries in the

surrounding villages of

Mantineia

and, notably,

Tegea

. In Sparta itself, the temple of Athena

Khalkíoikos (Athena “of the Brazen House”, often

latinized

as Chalcioecus) was the

grandest and located on the Spartan acropolis; presumably it had a roof of

bronze. The forecourt of the Brazen House was the place where the most solemn

religious functions in Sparta took place.

Tegea was an important religious center of ancient Greece, containing the

Temple of Athena Alea

. The temenos was founded by

Aleus

,

Pausanias

was informed. Votive bronzes at the

site from the Geometric and Archaic periods take the forms of horses and deer;

there are

sealstone

and

fibulae

. In the Archaic period the nine

villages that underlie Tegea banded together in a

synoecism

to form one city. Tegea was listed in

Homer

‘s

Catalogue of Ships

as one of the cities that

contributed ships and men for the

Achaean assault on Troy

.

Judgment of Paris

Aphrodite is being surveyed by Paris, while Athena (the leftmost

figure) and Hera stand nearby.

El Juicio de Paris

by

Enrique Simonet

, ca. 1904

All the gods and goddesses as well as various mortals were invited to the

marriage of Peleus

and

Thetis

(the eventual parents of

Achilles

). Only

Eris

, goddess of discord, was not invited. She

was annoyed at this, so she arrived with a golden apple inscribed with the word

καλλίστῃ (kallistēi, “for the fairest”), which she threw among the goddesses.

Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena all claimed to be the fairest, and thus the rightful

owner of the apple.

The goddesses chose to place the matter before Zeus, who, not wanting to

favor one of the goddesses, put the choice into the hands of Paris, a

Trojan prince. After bathing in the spring of

Mount Ida

(where Troy was situated), the

goddesses appeared before Paris. The goddesses undressed and presented

themselves to Paris naked, either at his request or for the sake of winning.

Paris is awarding the apple to Aphrodite, while Athena makes a face.

Urteil des Paris by

Anton Raphael Mengs

, ca. 1757

Still, Paris could not decide, as all three were ideally beautiful, so they

resorted to bribes. Hera tried to bribe Paris with control over all

Asia and Europe

, while Athena offered wisdom, fame and

glory in battle, but Aphrodite came forth and whispered to Paris that if he were

to choose her as the fairest he would have the most beautiful mortal woman in

the world as a wife, and he accordingly chose her. This woman was

Helen

, who was, unfortunately for Paris,

already married to King

Menelaus

of

Sparta

. The other two goddesses were enraged by

this and through Helen’s abduction by Paris they brought about the

Trojan War

.

The Parthenon

, Temple of Athena

Parthenos

Masculinity and

feminism

Athena had an “androgynous compromise” that allowed her traits and what she

stood for to be attributed to male and female rulers alike over the course of

history (such as Marie de’ Medici, Anne of Austria, Christina of Sweden, and

Catherine the Great)

J.J. Bachofen advocated that Athena was originally a maternal figure stable

in her security and poise but was caught up and perverted by a patriarchal

society; this was especially the case in Athens. The goddess adapted but could

very easily be seen as a god. He viewed it as “motherless paternity in the place

of fatherless maternity” where once altered, Athena’s character was to be

crystallized as that of a patriarch.

Whereas Bachofen saw the switch to paternity on Athena’s behalf as an

increase of power, Freud on the contrary perceived Athena as an “original mother

goddess divested of her power”. In this interpretation, Athena was demoted to be

only Zeus’s daughter, never allowed the expression of motherhood. Still more

different from Bachofen’s perspective is the lack of role permanency in Freud’s

view: Freud held that time and differing cultures would mold Athena to stand for

what was necessary to them.

Antigonus II Gonatas (Greek:

Αντίγονος B΄ Γονατᾶς “knock-knees” 319 BC—239 BC) was a powerful ruler

who firmly established the

Antigonid dynasty

in

Macedonia

and acquired fame for his victory over the

Gauls who had

invaded the Balkans

.

//

Birth

and family

Antigonus Gonatas was born around 319 BC, probably in

Gonnoi

in

Thessaly

or

his name is derived from an iron plate protecting the knee (Ancient

Greek: gonu-gonatos, English: knee;

Modern

Greek

: epigonatida, English: kneecap). He was related to the

most powerful of the

Diadochi

(the generals of

Alexander

who divided the empire after his death in 323 BC). Antigonus’s

father was

Demetrius Poliorcetes

, who was the son of

Antigonus

, who then controlled much of Asia. His mother was

Phila

, the daughter of

Antipater

.

The latter controlled Macedonia and Greece and was recognized as regent of the

empire, which in theory remained united. In this year, however, Antipater died,

leading to further struggles for territory and dominance.

The careers of Antigonus’s grandfather and father showed

great swings in fortune. After coming closer than anyone to reuniting the empire

of Alexander, Antigonus Monophthalmus was defeated and killed in the great

battle of Ipsus

in 301 BC and the territory he formerly controlled was

divided among his enemies,

Cassander

,

Ptolemy

,

Lysimachus

,

and

Seleucus

.

Demetrius’s

general

The fate of Antigonus Gonatas, now 18, was closely tied with

that of his father Demetrius who escaped from the battle with 9,000 troops.

Jealousy among the victors eventually allowed Demetrius to regain part of the

power his father had lost. He conquered

Athens

and much

of Greece and in 294 BC he seized the throne of Macedonia from

Alexander

, the son of Cassander.

Because Antigonus Gonatas was the grandson of Antipater and

the nephew of Cassander, through his mother, his presence helped to reconcile

the supporters of these former kings to the rule of his father.

In 292 BC, while Demetrius was campaigning in

Boeotia

, he

received news that Lysimachus, the ruler of

Thrace

and the

enemy of his father had been taken prisoner by

Dromichaetes

, a barbarian. Hoping to seize Lysimachus’s territories in

Thrace and Asia, Demetrius, delegated command of his forces in Boeotia to

Antigonus and immediately marched North. While he was away, the Boeotians rose

in rebellion, but were defeated by Antigonus, who bottled them up in

Thebes

.

After the failure of his expedition to Thrace, Demetrius

rejoined his son at the siege of Thebes. As the Thebans defended their city

stubbornly, Demetrius often forced his men to attack the city at great cost,

even though there was little hope of capturing it. It is said that, distressed

by the heavy losses, Antigonus asked his father: “Why, father, do we allow these

lives to be thrown away so unnecessarily?” Demetrius appears to have showed his

contempt for the lives of his soldiers by replying: “We don’t have to find

rations for the dead.” But he also showed a similar disregard for his own life

and was badly wounded at the siege by a bolt through the neck.

In 291 BC, Demetrius finally took the city after using siege

engines to demolish its walls. But control of Macedonia and most of Greece was

merely a stepping stone to his plans for further conquest. He aimed at nothing

less than the revival of Alexander’s empire and started making preparations on a

grand scale, ordering the construction of a fleet of 500 ships, many of them of

unprecedented size.

Such preparations and the obvious intent behind them,

naturally alarmed the other kings, Seleucus, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and

Pyrrhus

, who immediately formed an alliance. In the Spring of 288 BC

Ptolemy’s fleet appeared off Greece, inciting the cities to revolt. At the same

time, Lysimachus attacked Macedonia from the East while Pyrrhus did so from the

West. Demetrius left Antigonus in control of Greece, while he hurried to

Macedonia.

By now the Macedonians had come to resent the extravagance

and arrogance of Demetrius, and were not prepared to fight a difficult campaign

for him. In 287 BC, Pyrrhus took the Macedonian city of

Verroia

and Demetrius’s army promptly deserted and went over to the enemy

who was much admired by the Macedonians for his bravery. At this change of

fortune, Phila, the mother of Antigonus, killed herself with poison. Meanwhile

in Greece, Athens revolted. Demetrius therefore returned and besieged the city,

but he soon grew impatient and decided on a more dramatic course. Leaving

Antigonus in charge of the war in Greece, he assembled all his ships and

embarked with 11,000 infantry and all his cavalry to attack

Caria

and

Lydia

, provinces

of Lysimachus.

By separating himself from his son and departing into Asia,

Demetrius seemed to take his bad luck with him, but in reality it was the fear

and the jealousy of the other kings. As Demetrius was chased across

Asia Minor

to the

Taurus Mountains

by the armies of Lysimachus and Seleucus, Antigonus

attained success in Greece. Ptolemy’s fleet was driven off and Athens

surrendered.

In

the wilderness

In 285 BC, Demetrius, worn down by his fruitless campaign,

surrendered to Seleucus. At this point he wrote to son and his commanders in

Athens and Corinth

telling them to henceforth consider him a dead man and to ignore any

letters they might receive written under his seal. Macedonia, meanwhile had been

divided between Pyrrhus and Lysimachus, but like two wolves sharing a piece of

meat, they soon fought over it with the result that Lysimachus drove Pyrrhus out

and took over the whole kingdom.

Following the capture of his father, Antigonus proved himself

a dutiful son. He wrote to all the kings, especially Seleucus, offering to

surrender all the territory he controlled and proposing himself as a hostage for

his father’s release, but to no avail. In 283 BC, at the age of 55, Demetrius

died in captivity in Syria. When Antigonus heard that his father’s remains were

being brought to him, he put to sea with his entire fleet, met Seleucus’s ships

near the Cyclades

, and took the relics to Corinth with great ceremony. After this,

the remains were interred at the town of

Demetrias

that his father had founded in

Thessaly

.

In 282 BC, Seleucus declared war on Lysimachus and the next

year defeated and killed him at the

battle of Corupedium

in Lydia. He then crossed to Europe to claim Thrace and

Macedonia, but

Ptolemy Ceraunus

, the son of Ptolemy, murdered him and seized the Macedonian

throne. Antigonus decided the time was ripe to take back his father’s kingdom,

but when he marched North, Ptolemy Ceraunus defeated his army.

Ptolemy’s success, however, was short lived. In the Winter of

279 BC, a great horde of

Gauls descended on

Macedonia from the northern forests, crushed Ptolemy’s army, and killed him in

battle, starting two years of complete anarchy in the kingdom. After plundering

Macedonia, the Gauls invaded Greece. Antigonus cooperated in the defense of

Greece against the barbarians, but it was the

Aetolians

who took the lead in defeating the

Gauls

. In 278 BC, a Greek army with a large

Aetolian

contingent resisted the Gauls at

Thermopylae

and Delphi

, inflicting heavy casualties and forcing them to retreat.

The next year (277 BC), Antigonus, sailed to the

Hellespont

,

landing near

Lysimachia

at the neck of the

Thracian Chersonese

. When an army of Gauls under the command of

Cerethrius

appeared, Antigonus laid an ambush. He abandoned his camp and beached his ships,

then concealed his men. The Gauls looted the camp, but when they started to

attack the ships, Antigonus’s army appeared, trapping them with the sea to their

rear. In this way, Antigonus was able to inflict a crushing defeat on them and

claim the Macedonian throne. It was around this time, under these favorable

omens, that his son and successor,

Demetrius II Aetolicus

was born.

King

of Macedonia

Antigonus

against Pyrrhus

Pyrrhus

, king of

Epirus

, Macedonia’s Western neighbor, was a general of mercurial ability,

widely renowned for his bravery, but he did not apply his talents sensibly and

often snatched after vain hopes, so that Antigonus used to compare him to a dice

player, who had excellent throws, but did not know how to use them. When the

Gauls defeated Ptolemy Ceraunus and the Macedonian throne became vacant, Pyrrhus

was occupied in his campaigns overseas. Hoping to conquer first

Italy

and then

Africa, he got involved in wars against

Rome

and Carthage

, the two most powerful states in the Western

Mediterranean

. He then lost the support of the Greek cities in Italy and

Sicily

by his

haughty behavior. Needing reinforcements, he wrote to Antigonus as a fellow

Greek king, asking him for troops and money, but Antigonus politely refused. In

275 BC, the Romans fought Pyrrhus at the

Battle of Beneventum

which ended inconclusively, although many modern

sources wrongly state that Pyrrhus lost the battle. Pyrrhus had been drained by

his recent wars in Sicily, and by the earlier Pyrrhic victories over the Romans,

and thus decided to end his campaign in Italy and return to Epirus.

Pyrrhus’s retreat from Italy, however, proved very unlucky

for Antigonus. Returning to Epirus with an army of eight thousand foot and five

hundred horse, he was in need of money to pay them. This encouraged him to look

for another war, so the next year, after adding a force of Gallic mercenaries to

his army, he invaded Macedonia with the intention of filling his coffers with

plunder. The campaign however went better than expected. Making himself master

of several towns and being joined by two thousand deserters, his hopes started

to grow and he went in search of Antigonus, attacking his army in a narrow pass

and throwing it into disorder. Antigonus’s Macedonian troops retreated, but his

own body of Gallic mercenaries, who had charge of his elephants, stood firm

until Pyrrhus’s troops surrounded them, whereupon they surrendered both

themselves and the elephants. Pyrrhus now chased after the rest of Antigonus’s

army which, demoralized by its earlier defeat, declined to fight. As the two

armies faced each other, Pyrrhus called out to the various officers by name and

persuaded the whole body of infantry to desert. Antigonus escaped by concealing

his identity. Pyrrhus now took control of upper Macedonia and Thessaly while

Antigonus held onto the coastal towns.

But like the dice player who wasted his good fortune, Pyrrhus

now wasted his victory. Taking possession of

Aegae

, the

ancient capital of Macedonia, he installed a garrison of Gauls who greatly

offended the Macedonians by digging up the tombs of their kings and leaving the

bones scattered about as they searched for gold. He also neglected to finish off

his enemy. Leaving him in control of the coastal cities, he contented himself

with insults. He called Antigonus a shameless man for still wearing the purple,

but he did little to destroy the remnants of his power.

Before this campaign was finished, Pyrrhus had embarked upon

a new one. In 272 BC,

Cleonymus

, an important

Spartan

,

invited him to invade

Laconia

.

Gathering an army of twenty-five thousand foot, two thousand horse, and

twenty-four elephants, he crossed over to the

Peloponnese

and occupied

Megalopolis

in

Arcadia

.

Antigonus, after reoccupying part of Macedonia, gathered what forces he could

and sailed to Greece to oppose him. As a large part of the Spartan army led by

king Areus

was in Crete

at

the time, Pyrrhus had great hopes of taking the city easily, but the citizens

organized stout resistance, allowing one of Antigonus’s commanders, Aminias, the

Phocian

, to

reach the city with a force of mercenaries from Corinth. Soon after this, the

Spartan king, Areus, returned from Crete with 2.000 men. These reinforcements

stiffened resistance and Pyrrhus, finding that he was losing men to desertion

every day, broke off the attack and started to plunder the country.

The most important Peloponnesian city after Sparta was

Argos

. The two

chief men,

Aristippus

and

Aristeas

were keen rivals. As Aristippus was an ally of Antigonus, Aristeas

invited Pyrrhus to come to Argos to help him take over the city. Antigonus,

aware that Pyrrhus was advancing on Argos, marched his army there as well,

taking up a strong position on some high ground near the city. When Pyrrhus

learned this, he encamped about

Nauplia

and

the next day dispatched a herald to Antigonus, calling him a coward and

challenging him to come down and fight on the plain. Antigonus replied that he

would choose his own moment to fight and that if Pyrrhus was weary of life, he

could find many ways to die.

The Argives, fearing that their territory would become a war

zone, sent deputations to the two kings begging them to go elsewhere and allow

their city to remain neutral. Both kings agreed, but Antigonus won over the

trust of the Argives by surrendering his son as a hostage for his pledge.

Pyrrhus, who had recently lost a son in the retreat from Sparta, did not.

Indeed, with the help of Aristeas, he was plotting to seize the city. In the

middle of the night, he marched his army up to the city walls and entered

through a gate that Aristeas had opened. His Gallic troops seized the market

place, but he had difficulty getting his elephants into the city through the

small gates. This gave the Argives time to rally. They occupied strong points

and sent messengers asking Antigonus for help.

When Antigonus heard that Pyrrhus had treacherously attacked

the city, he advanced to the walls and sent a strong force inside to help the

Argives. At the same time Areus arrived with a force of 1.000 Cretans and

light-armed Spartans. These forces attacked the Gauls in the market place.

Pyrrhus, realizing that his Gallic troops were hard pressed, now advanced into

the city with more troops, but in the narrow streets this soon led to confusion

as men got lost and wandered around. The two forces now paused and waited for

daylight. When the sun rose, Pyrrhus saw how strong the opposition was and

decided the best thing was to retreat. Fearing that the gates would be too

narrow for his troops to easily exit the city, he sent a message to his son,

Helenus

, who was outside with the main body of the army, asking him to break

down a section of the walls. The messenger, however, failed to convey his

instructions clearly. Misunderstanding what was required, Helenus took the rest

of the elephants and some picked troops and advanced into the city to help his

father.

With some of his troops trying to get out of the city and

others trying to get in, Pyrrhus’s army was now thrown into confusion. This was

made worse by the elephants. The largest one had fallen across the gateway and

was blocking the way, while another elephant, called Nicon, was trying to find

its rider. This beast surged against the tide of fugitives, crushing friend and

foe alike, until it found its dead master, whereupon it picked him up, placed

him on its tusks, and went on the rampage. In this chaos Pyrrhus was struck down

by a tile thrown by an old woman and killed by Zopyrus, a soldier of Antigonus.

Thus ended the career of the most famous soldier of his time.

Alcyoneus, one of Antigonus’s sons, heard that Pyrrhus had

been killed. Taking the head, which had been cut off by Zopyrus, he rode to

where his father was and threw it at his feet. Far from being delighted,

Antigonus was angry with his son and struck him, calling him a barbarian and

drove him away. He then covered his face with his cloak and burst into tears.

The fate of Pyrrhus reminded him all too clearly of the tragic fates of his own

grandfather and his father who had suffered similar swings of fortune. He then

had Pyrrhus’s body cremated with great ceremony.

After the death of Pyrrhus, his whole army and camp

surrendered to Antigonus, greatly increasing his power. Later, Alcyoneus

discovered Hellenicus, Pyrrhus’s son, disguised in threadbare clothes. He

treated him kindly and brought him to his father who was more pleased with his

behaviour. “This is better than what you did before, my son,” he said, “but why

leave him in these clothes which are a disgrace to us now that we know ourselves

the victors?” Greeting him courteously, Antigonus treated Helenus as an honored

guest and sent him back to Epirus.

This was not the end of Antigonus’ problems with Epirus:

shortly after

Alexander II

, the son of Pyrrhus and his successor as king of Epirus,

repeated his father’s adventure by conquering Macedonia. But only a few years

after Alexander was not only expelled from Macedonia by Antigonus’ son

Demetrius, but he also lost Epirus and had to go into exile in

Acarnania

.

His exile didn’t last long, as the Macedonians had at the end to abandon Epirus

under pressure from Alexander’s allies, the Acarnanians and the

Aetolians

. Alexander seems to have died about 242 BC leaving his country

under the regency of his wife

Olympias

who proved anxious to have good relations with Epirus’ powerful

neighbor, as was sanctioned by the marriage between the regent’s daughter

Phthia

and Antigonus’ son and heir Demetrius.

Chremonidean

War

With the restoration of the territories captured by Pyrrhus,

and with grateful allies in Sparta and Argos, and garrisons in Corinth and other

cities, Antigonus securely controlled Macedonia and Greece. The careful way he

guarded his power shows that he wished to avoid the vicissitudes of fortune that

had characterized the careers of his father and grandfather. Aware that the

Greeks loved freedom and autonomy, he was careful to grant a semblance of this

in as much as it did not clash with his own power. Also, he tried to avoid the

odium that direct rule brings by controlling the Greeks through intermediaries.

It is for this reason that

Polybius

says, “No man ever set up more absolute rulers in Greece than Antigonus.”

The next stage of Antigonus’s career is not documented and

what we know has been patched together from a few historical fragments:

Antigonus seems to have been on very good terms with

Antiochus

, the

Seleucid

ruler of Asia, whose love for

Stratonice

, the sister of Antigonus, is very famous. Such an alliance

naturally threatened the third

successor state

,

Ptolemaic Egypt

. In Greece, Athens and Sparta, once the dominant states,

naturally resented the domination of Antigonus. The pride, which in the past had

made these cities mortal enemies, now served to unite them. In 267 BC, probably

with encouragement from Egypt, an Athenian by the name of

Chremonides

persuaded the Athenians to join the Spartans in declaring war on

Antigonus (see

Chremonidean War

).

The Macedonian king responded by ravaging the territory of

Athens with an army while blockading them by sea. In this campaign he also

destroyed the grove and temple of Poseidon that stood at the entrance to

Attica

near the

border with Megara

.

To support the Athenians and prevent the power of Antigonus from growing too

much,

Ptolemy II Philadelphus

, the king of Egypt, sent a fleet to break the

blockade. The Egyptian admiral,

Patroclus

, landed on a small uninhabited island near

Laurium

and

fortified it as a base for naval operations.

The Seleucid Empire had signed a peace treaty with Egypt, but

Antiochus’s son-in-law,

Magas

, king of

Cyrene

, persuaded Antiochus to take advantage of the war in Greece to attack

Egypt. To counter this, Ptolemy dispatched a force of pirates and freebooters to

raid and attack the lands and provinces of Antiochus, while his army fought a

defensive campaign, holding back the stronger Seleucid army. Although

successfully defending Egypt, Ptolemy II was unable to save Athens from

Antigonus. In 263 BC, the Athenians and Spartans, worn down by several years of

war and the devastation of their lands, made peace with Antigonus, who thus

retained his hold on Greece.

Ptolemy II continued to interfere in the affairs of Greece

and this led to war in 261 BC. After two years in which little changed,

Antiochus II

, the new Seleucid king, made a military agreement with

Antigonus, and the

Second Syrian War

began. Under the combined attack, Egypt lost ground in

Anatolia

and Phoenicia

,

and the city of Miletus

, held by its ally,

Timarchus

, was seized by

Antiochus II Theos

. In 255 BC, Ptolemy made peace, ceding lands to the

Seleucids and confirming Antigonus in his mastery of Greece.

Antigonus

against Aratus

Having successfully repelled the external threat to his

control of Greece, the main danger to the power of Antigonus lay in the Greek

love of liberty. In 251 BC,

Aratus

, a young nobleman in the city of

Sicyon

expelled

the tyrant

Nicocles

,

who had ruled with the acquiescence of Antigonus, freed the people, and recalled

the exiles. This led to confusion and division within the city. Fearing that

Antigonus would exploit these divisions to attack the city, Aratus applied for

the city to join the

Achaean League

, a league of a few small

Achaean

towns

in the Pelopennese.

Preferring to use guile rather than military power, Antigonus

sought to regain control over Sicyon through winning the young man over to his

side. Accordingly, he sent him a gift of 25

talents

, but, Aratus, instead of being corrupted by this wealth, immediately

gave it away to his fellow citizens. With this money and another sum he received

from

Ptolemy II Philadelphus

, he was able to reconcile the different parties in

Sicyon and unite the city.

Antigonus was troubled by the rising power and popularity of

Aratus. If he were to receive extensive military and financial support from

Ptolemy, Aratus would be able to threaten his position. He decided therefore to

either win him over to his side or at least discredit him with Ptolemy. In order

to do this, he showed him great marks of favour. When he was sacrificing to the

gods in Corinth, he sent portions of the meat to Aratus at Sicyon, and

complimented Aratus in front of his guests: “I thought this Sicyonian youth was

only a lover of liberty and of his fellow-citizens, but now I look upon him as a

good judge of the manners and actions of kings. For formerly he despised us,

and, placing his hopes further off, admired the Egyptians, hearing much of their

elephants, fleets, and palaces. But after seeing all these at a nearer distance,

and perceiving them to be but mere stage props and pageantry, he has now come

over to us. And for my part I willingly receive him, and, resolving to make

great use of him myself, command you to look upon him as a friend.” These words

were readily believed by many, and when they were reported to Ptolemy, he half

believed them.

But Aratus was far from becoming a friend of Antigonus, whom

he regarded as the oppressor of Greek freedom. In 243 BC, in an attack by night,

he seized the

Acrocorinth

, the strategically important fort by which Antigonus controlled

the

Isthmus

and thus the Pelopennese. When news of this success reached Corinth,

the Corinthians rose in rebellion, overthrew Antigonus’ party, and joined the

Achaean League. Next Aratus took the port of

Lechaeum

and

captured 25 of Antigonus’s ships.

This setback for Antigonus, sparked a general uprising

against Macedonian power. The

Megarians

revolted and together with the

Troezenians

and Epidaurians

enrolled in the Achaean League. With this increased strength,

Aratus invaded the territory of Athens and plundered

Salamis

. Every Athenian freemen whom he captured was sent back to the

Athenians without ransom to encourage them to join the rebellion. The

Macedonians, however, retained their hold on Athens and the rest of Greece.

Relations

with India

Antigonus is mentioned in the

Edicts of Ashoka

, as one of the recipients of the Indian Emperor

Ashoka

‘s Buddhist

proselytism.

No Western historical record of this event remain.

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of

herbal medicine

, for men and animals, in the territories of the Hellenistic

kings

Death

and appraisal

In 239 BC, Antigonus died at the age of 80 and left his

kingdom to his son

Demetrius II

, who was to reign for the next 10 years. Except for a short

period when he defeated the Gauls, Antigonus was not an heroic or successful

military leader. His skills were mainly political. He preferred to rely on

cunning, patience, and persistence to achieve his goals. While more brilliant

leaders, like his father Demetrius, and Pyrrhus his neighbour, aimed higher and

fell lower, Antigonus achieved a measure of mediocre security. By dividing the

Greeks and ruling them indirectly through tyrants, however, he retarded their

political development so that they later fell an easy prey for the

Roman

conquest. It is also said of him that he gained the affection of his

subjects by his honesty and his cultivation of the arts, which he accomplished

by gathering round him distinguished literary men, in particular philosophers,

poets, and historians.

|