|

Claudius

–

Roman Emperor

: 41-54 A.D. –

Bronze Quadrans 17mm (2.87 grams) Rome mint: 42 A.D.

Reference: RIC 90, BN 195, S 1865, C 72

TI CLAVDIVS CAESAR AVG, Modius.

PON M TR P IMP PP COS II around large S C.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

MODIVS, a bushel measure– of wheat for instance, or any dry or solid commodity.

It contained the third part of an amphora, and four of these measures per month

was the ordinary allowance given to slaves.

On Roman coins we see the modius represented with corn-ears, and sometimes a

poppy hanging or rising from it– and having reference to distributions of wheat

to the people, by various Emperors, such as Nerva, Vespasian, M. Aurelius, and

Domitian. On a denarius of Nerva, with the legend COS IIII , there is a modius

with six ears of corn. The modius is also the sign of the AEdileship on coins of

the Papia and other families, and is represented full of wheat, between two ears

of corn, as the symbol and attribute of Abundantia and of Annona (see the

words). The coins of Nero, and from that Emperor down to Gallienus, furnish

frequent examples of this figure as indicating the fruits of fertility, whether

domestic or foreign; and the Imperial liberality and providence in procuring,

and in bestowing them on the people

_01.jpg/250px-Claudius_(M.A.N._Madrid)_01.jpg) Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (1 August 10 BC – 13 Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (1 August 10 BC – 13

October AD 54) (Tiberius Claudius Drusus from birth to AD 4, then

Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus from then until his accession) was the

fourth

Roman

Emperor

, a member of the

Julio-Claudian dynasty

, ruling from 24 January AD 41 to his death in AD 54.

Born in Lugdunum

in Gaul

(modern-day Lyon

,

France

), to

Drusus

and

Antonia Minor

, he was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside

Italia

.

He was reportedly afflicted with some type of disability, and his family had

virtually excluded him from public office until his

consulship

with

his nephew Caligula

in AD 37. This infirmity may have saved him from the fate of many

other Roman nobles during the purges of

Tiberius

‘

and Caligula’s reigns; potential enemies did not see him as a serious threat to

them. His very survival led to his being declared emperor (reportedly because

the

Praetorian Guard

insisted) after Caligula’s assassination, at which point he

was the last adult male of his family.

Despite his lack of political experience, Claudius proved to be an able

administrator and a great builder of public works. His reign saw an expansion of

the empire, including the

conquest of Britain

. He took a personal interest in the law, presided at

public trials, and issued up to 20 edicts a day; however, he was seen as

vulnerable throughout his rule, particularly by the nobility. Claudius was

constantly forced to shore up his position. This resulted in the deaths of many

senators

. Claudius also suffered setbacks in his personal life, one of which

may have led to his murder. These events damaged his reputation among the

ancient writers, though more recent historians have revised this opinion.

//

Family

and early life

Claudius was born on 1 August 10 BC, in

Lugdunum

,

Gaul, on the day of

the dedication of an altar to

Augustus

.

His parents were

Nero Claudius Drusus

and

Antonia

, and he had two older siblings named

Germanicus

and Livilla

.

Antonia may have had two other children who died young, as well.

His maternal grandparents were

Mark

Antony

and

Octavia Minor

, Caesar Augustus’ sister, and as such he was the great-great

grandnephew of

Gaius

Julius Caesar

. His paternal grandparents were

Livia

, Augustus’

third wife, and

Tiberius Claudius Nero

. During his reign, Claudius revived the rumor that

his father Drusus was actually the illegitimate son of Augustus, to give the

false appearance that Augustus was Claudius’ paternal grandfather.

In 9 BC, Drusus unexpectedly died on campaign in Germania, possibly from

illness. Claudius was then left to be raised by his mother, who never remarried.

When Claudius’ disability became evident, the relationship with his family

turned sour. Antonia referred to him as a monster, and used him as a standard

for stupidity. She seems to have passed her son off on his grandmother Livia for

a number of years.[1]

Livia was little kinder, and often sent him short, angry letters of reproof. He

was put under the care of a “former mule-driver”[2]

to keep him disciplined, under the logic that his condition was due to laziness

and a lack of will-power. However, by the time he reached his teenage years his

symptoms apparently waned and his family took some notice of his scholarly

interests. In AD 7, Livy

was hired to tutor him in history, with the assistance of Sulpicius

Flavus. He spent a lot of his time with the latter and the philosopher

Athenodorus

. Augustus, according to a letter, was surprised at the clarity

of Claudius’ oratory.[3]

Expectations about his future began to increase.

Ironically, it was his work as a budding

historian

that destroyed his early career. According to Vincent Scramuzza and others,

Claudius began work on a history of the

Civil Wars

that was either too truthful or too critical of Octavian.[4]

In either case, it was far too early for such an account, and may have only

served to remind Augustus that Claudius was Antony’s descendant. His mother and

grandmother quickly put a stop to it, and this may have proved to them that

Claudius was not fit for public office. He could not be trusted to toe the

existing party line. When he returned to the narrative later in life, Claudius

skipped over the wars of the second triumvirate altogether. But the damage was

done, and his family pushed him to the background. When the

Arch

of Pavia

was erected to honor the imperial clan in AD 8, Claudius’ name (now Tiberius

Claudius Nero Germanicus after his elevation to

paterfamilias

of Claudii Nerones on the adoption of his brother) was

inscribed on the edge—past the deceased princes,

Gaius

and Lucius

, and Germanicus’ children. There is some speculation that the

inscription was added by Claudius himself decades later, and that he originally

did not appear at all.[5]

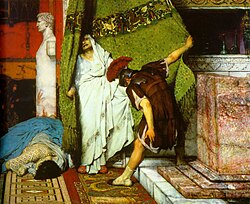

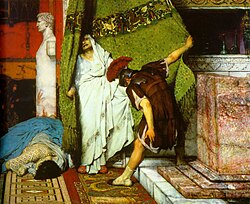

Gratus proclaims Claudius emperor. Detail from A Roman Emperor

41AD, by

Lawrence Alma-Tadema

. Oil on canvas, c. 1871.

When Augustus died in AD 14, Claudius — then 23 — appealed to his uncle

Tiberius

to

allow him to begin the

cursus honorum

. Tiberius, the new emperor, responded by granting

Claudius consular ornaments. Claudius requested office once more and was

snubbed. Since the new emperor was not any more generous than the old, Claudius

gave up hope of public office and retired to a scholarly, private life.

Despite the disdain of the imperial family, it seems that from very early on

the general public respected Claudius. At Augustus’ death, the

equites

, or knights, chose Claudius to head their delegation. When his

house burned down, the Senate demanded it be rebuilt at public expense. They

also requested that Claudius be allowed to debate in the senate. Tiberius turned

down both motions, but the sentiment remained. During the period immediately

after the death of Tiberius’ son,

Drusus

, Claudius was pushed by some quarters as a potential heir. This again

suggests the political nature of his exclusion from public life. However, as

this was also the period during which the power and terror of the Praetorian

Sejanus

was

at its peak, Claudius chose to downplay this possibility.

After the death of Tiberius the new emperor

Caligula

(the son of Claudius’ brother

Germanicus

)

recognized Claudius to be of some use. He appointed Claudius his co-consul in AD

37 in order to emphasize the memory of Caligula’s deceased father Germanicus.

Despite this, Caligula relentlessly tormented his uncle: playing practical

jokes, charging him enormous sums of money, humiliating him before the Senate,

and the like. According to

Cassius

Dio

, as well a possible surviving portrait, Claudius became very sickly and

thin by the end of Caligula’s reign, most likely due to stress.[6]

Reign

Accession

as emperor

On 24 January, AD 41, Caligula was assassinated by a broad-based

conspiracy

(including Praetorian commander

Cassius Chaerea

and several

Senators

). There is no evidence that Claudius had a direct hand in the

assassination

, although it has been argued that he knew about the plot —

particularly since he left the scene of the crime shortly before his nephew was

murdered.[7]

However, after the deaths of

Caligula’s wife

and daughter, it became apparent that Cassius intended to go beyond the terms of

the conspiracy and wipe out the imperial family. In the chaos following the

murder, Claudius witnessed the

German

guard

cut down several uninvolved noblemen, including many of his friends. He fled to

the palace to hide. According to tradition, a Praetorian named Gratus found him

hiding behind a curtain and suddenly declared him

princeps

.[8]

A section of the guard may have planned in advance to seek out Claudius, perhaps

with his approval. They reassured him that they were not one of the battalions

looking for revenge. He was spirited away to the Praetorian camp and put under

their protection.

The Senate quickly met and began debating a change of government, but this

eventually devolved into an argument over which of them would be the new

Princeps

.

When they heard of the Praetorians’ claim, they demanded that Claudius be

delivered to them for approval, but he refused, sensing the danger that would

come with complying. Some historians, particularly

Josephus

,[9]

claim that Claudius was directed in his actions by the

Judean

King

Herod Agrippa

. However, an earlier version of events by the same ancient

author downplays Agrippa’s role[10]

— so it is not known how large a hand he had in things. Eventually the Senate

was forced to give in and, in return, Claudius pardoned nearly all the

assassins.

Claudius took several steps to legitimize his rule against potential

usurpers, most of them emphasizing his place within the Julio-Claudian family.

He adopted the name “Caesar” as a

cognomen

—

the name still carried great weight with the populace. In order to do so, he

dropped the cognomen “Nero” which he had adopted as paterfamilias of the Claudii

Nerones when his brother Germanicus was adopted out. While he had never been

adopted by Augustus or his successors, he was the grandson of Octavia, and so

felt he had the right. He also adopted the name “Augustus” as the two previous

emperors had done at their accessions. He kept the honorific “Germanicus” in

order to display the connection with his heroic brother. He deified his paternal

grandmother Livia in order to highlight her position as wife of the divine

Augustus. Claudius frequently used the term “filius Drusi” (son of Drusus) in

his titles, in order to remind the people of his legendary father and lay claim

to his reputation.

Because he was proclaimed emperor on the initiative of the Praetorian Guard

instead of the Senate — the first emperor thus proclaimed — Claudius’ repute

suffered at the hands of commentators (such as

Seneca

). Moreover, he was the first Emperor who resorted to

bribery

as a

means to secure army loyalty. Tiberius and Augustus had both left gifts to the

army and guard in their

wills

,

and upon Caligula’s death the same would have been expected, even if no will

existed. Claudius remained grateful to the guard, however, issuing coins with

tributes to the praetorians in the early part of his reign.

Expansion

of the empire

Under Claudius, the empire underwent its first major expansion since the

reign of Augustus. The provinces of

Thrace

,

Noricum

,

Pamphylia

,

Lycia

, and

Judea

were

annexed

under various circumstances during his term. The annexation of

Mauretania

,

begun under Caligula, was completed after the defeat of rebel forces, and the

official division of the former client kingdom into two imperial provinces.

[11]

The

most important new expansion was the

conquest of Britannia

.[12]

In AD 43, Claudius sent

Aulus Plautius

with four

legions

to Britain (Britannia) after an appeal from an ousted tribal ally.

Britain was an attractive target for Rome because of its material wealth —

particularly mines and

slaves

. It

was also a haven for Gallic

rebels and the like, and so could not be left alone much longer.

Claudius himself traveled to the island after the completion of initial

offensives, bringing with him reinforcements and elephants. The latter must have

made an impression on the

Britons

when they were used in the capture of

Camulodunum

. He left after 16 days, but remained in the provinces for some

time. The Senate granted him a

triumph

for his efforts, as only members of the imperial family were allowed

such honors. Claudius later lifted this restriction for some of his conquering

generals. He was granted the honorific “Britannicus” but only accepted it on

behalf of his son, never using the title himself. When the British general

Caractacus

was captured in AD 50, Claudius granted him

clemency

. Caractacus lived out his days on land provided by the Roman state,

an unusual end for an enemy commander.

Claudius conducted a

census

in AD 48

that found 5,984,072 Roman citizens,[13]

an increase of around a million since the census conducted at Augustus’ death.

He had helped increase this number through the foundation of Roman colonies that

were granted blanket

citizenship

. These colonies were often made out of existing communities,

especially those with elites who could rally the populace to the Roman cause.

Several colonies were placed in new provinces or on the border of the empire in

order to secure Roman holdings as quickly as possible.

Judicial

and legislative affairs

Claudius personally judged many of the legal cases tried during his reign.

Ancient historians have many complaints about this, stating that his judgments

were variable and sometimes did not follow the law.[14]

He was also easily swayed. Nevertheless, Claudius paid detailed attention to the

operation of the judicial system. He extended the summer court session, as well

as the winter term, by shortening the traditional breaks. Claudius also made a

law requiring plaintiffs to remain in the city while their cases were pending,

as defendants had previously been required to do. These measures had the effect

of clearing out the docket. The minimum age for jurors was also raised to 25 in

order to ensure a more experienced jury pool.[15]

Claudius also settled disputes in the provinces. He freed the island of

Rhodes

from

Roman rule for their good faith and exempted

Troy from taxes.

Early in his reign, the

Greeks

and

Jews

of Alexandria

sent him two embassies at once after riots broke out between the

two communities. This resulted in the famous “Letter to the Alexandrians”, which

reaffirmed Jewish rights in the city but also forbade them to move in more

families en masse. According to

Josephus

,

he then reaffirmed the rights and freedoms of all the Jews in the empire.[16]

An investigator of Claudius’ discovered that many old Roman citizens based in

the modern city of Trento

were not in fact citizens.[17]

The emperor issued a declaration that they would be considered to hold

citizenship from then on, since to strip them of their status would cause major

problems. However, in individual cases, Claudius punished false assumption of

citizenship harshly, making it a capital offense. Similarly, any freedmen found

to be impersonating equestrians were sold back into slavery.[18]

Numerous edicts were issued throughout Claudius’ reign. These were on a

number of topics, everything from medical advice to moral judgments. Two famous

medical examples are one promoting

Yew

juice as a cure for snakebite,[19]

and another promoting public flatulence for good health.[20]

One of the more famous edicts concerned the status of sick slaves. Masters had

been abandoning ailing slaves at the

temple

of Aesculapius

to die, and then reclaiming them if they lived. Claudius

ruled that slaves who recovered after such treatment would be free. Furthermore,

masters who chose to kill slaves rather than take the risk were liable to be

charged with murder.[21]

Public

works

The Porta Maggiore in Rome

Claudius embarked on many public works throughout his reign, both in the

capital and in the provinces. He built two

aqueducts

, the

Aqua

Claudia

, begun by

Caligula

,

and the Anio Novus

. These entered the city in AD 52 and met at the famous

Porta Maggiore

. He also restored a third, the

Aqua Virgo

.

He paid special attention to transportation. Throughout

Italy

and the

provinces he built roads and canals. Among these was a large canal leading from

the Rhine

to the

sea, as well as a road from Italy to Germany — both begun by his father, Drusus.

Closer to Rome, he built a navigable canal on the

Tiber

, leading to

Portus

, his new

port just north of

Ostia

. This port was constructed in a semicircle with two

moles

and a lighthouse at its mouth. The construction also had the effect of

reducing flooding in Rome.

The port at Ostia was part of Claudius’ solution to the constant grain

shortages that occurred in winter, after the Roman shipping season. The other

part of his solution was to insure the ships of grain merchants who were willing

to risk traveling to Egypt in the off-season. He also granted their sailors

special privileges, including citizenship and exemption from the

Lex Papia-Poppaea

, a law that regulated marriage. In addition, he repealed

the taxes that Caligula

had instituted on food, and further reduced taxes on communities

suffering drought

or famine

.

The last part of Claudius’ plan was to increase the amount of arable land in

Italy. This was to be achieved by draining the

Fucine lake

, which would have the added benefit of making the nearby river

navigable year-round.

[22]

A

tunnel was dug through the lake bed, but the plan was a failure. The tunnel was

crooked and not large enough to carry the water, which caused it to back up when

opened. The resultant flood washed out a large gladiatorial exhibition held to

commemorate the opening, causing Claudius to run for his life along with the

other spectators. The draining of the lake was revisited many times in history,

including by emperors

Trajan

and

Hadrian

, and

Holy Roman Emperor

Frederick II

in the

Middle

Ages

. It was finally achieved by the Prince

Torlonia

in the 19th century, producing over 160,000 acres (650 km2)

of new arable land.[23]

He expanded the Claudian tunnel to three times its original size.

Claudius

and the Senate

Because of the circumstances of his accession, Claudius took great pains to

please the Senate. During regular sessions, the emperor sat among the Senate

body, speaking in turn. When introducing a law, he sat on a bench between the

consuls in his position as Holder of the Power of

Tribune

(The

emperor could not officially serve as a Tribune of the Plebes as he was a

Patrician

, but it was a power taken by previous rulers). He refused to

accept all his predecessors’ titles (including

Imperator

)

at the beginning of his reign, preferring to earn them in due course. He allowed

the Senate to issue its own bronze coinage for the first time since Augustus. He

also put the imperial provinces of

Macedonia

and

Achaea

back under Senate control.

Claudius set about remodeling the Senate into a more efficient,

representative body. He chided the senators about their reluctance to debate

bills introduced by himself, as noted in the fragments of a surviving speech:

If you accept these proposals, Conscript Fathers, say so at once and

simply, in accordance with your convictions. If you do not accept them,

find alternatives, but do so here and now; or if you wish to take time

for consideration, take it, provided you do not forget that you must be

ready to pronounce your opinion whenever you may be summoned to meet. It

ill befits the dignity of the Senate that the consul designate should

repeat the phrases of the consuls word for word as his opinion, and that

every one else should merely say ‘I approve’, and that then, after

leaving, the assembly should announce ‘We debated’.[24]

In AD 47 he assumed the office of

Censor

with

Lucius Vitellius

, which had been allowed to lapse for some time. He struck

the names of many senators and equites who no longer met qualifications, but

showed respect by allowing them to resign in advance. At the same time, he

sought to admit eligible men from the provinces. The

Lyons Tablet

preserves his speech on the admittance of Gallic senators, in

which he addresses the Senate with reverence but also with criticism for their

disdain of these men. He also increased the number of

Patricians

by adding new families to the dwindling number of noble lines.

Here he followed the precedent of

Lucius Junius Brutus

and

Julius Caesar

.

Nevertheless, many in the Senate remained hostile to Claudius, and many plots

were made on his life. This hostility carried over into the historical accounts.

As a result, Claudius was forced to reduce the Senate’s power for efficiency.

The administration of Ostia was turned over to an imperial

Procurator

after construction of the port. Administration of many of the

empire’s financial concerns was turned over to imperial appointees and freedmen.

This led to further resentment and suggestions that these same freedmen were

ruling the emperor.

Several

coup

attempts were made during Claudius’ reign, resulting in the deaths of

many senators.

Appius Silanus

was executed early in Claudius’ reign under questionable

circumstances. Shortly after, a large rebellion was undertaken by the Senator

Vinicianus and

Scribonianus

, the governor of

Dalmatia

and gained quite a few senatorial supporters. It ultimately failed because of

the reluctance of Scribonianus’ troops, and the

suicide

of

the main conspirators. Many other senators tried different conspiracies and were

condemned. Claudius’ son-in-law

Pompeius Magnus

was executed for his part in a conspiracy with his father

Crassus Frugi. Another plot involved the consulars Lusiius Saturninus, Cornelius

Lupus, and Pompeius Pedo. In AD 46,

Asinius Gallus

, the grandson of

Asinius Pollio

, and Statilius Corvinus were exiled for a plot hatched with

several of Claudius’ own freedmen.

Valerius Asiaticus

was executed without public trial for unknown reasons.

The ancient sources say the charge was

adultery

,

and that Claudius was tricked into issuing the punishment. However, Claudius

singles out Asiaticus for special damnation in his speech on the Gauls, which

dates over a year later, suggesting that the charge must have been much more

serious. Asiaticus had been a claimant to the throne in the chaos following

Caligula’s death and a co-consul with the Statilius Corvinus mentioned above.

Most of these conspiracies took place before Claudius’ term as

Censor

, and may have induced him to review the Senatorial rolls. The

conspiracy of

Gaius

Silius

in the year after his Censorship, AD 48, is detailed in the section

discussing Claudius’ third wife,

Messalina

. Suetonius states that a total of 35 senators and 300 knights were

executed for offenses during Claudius’ reign.[25]

Needless to say, the necessary responses to these conspiracies could not have

helped Senate-emperor relations.

The

Secretariat and centralization of powers

Claudius was hardly the first emperor to use

freedmen

to

help with the day-to-day running of the empire. He was, however, forced to

increase their role as the powers of the

Princeps

became more centralized and the burden larger. This was partly due to the

ongoing hostility of the senate, as mentioned above, but also due to his respect

for the senators. Claudius did not want free-born magistrates to have to serve

under him, as if they were not peers.

The secretariat was divided into bureaus, with each being placed under the

leadership of one freedman.

Narcissus

was the secretary of correspondence.

Pallas

became the secretary of the treasury.

Callistus

became secretary of justice. There was a fourth bureau for

miscellaneous issues, which was put under

Polybius

until his execution for treason. The freedmen could also officially

speak for the emperor, as when Narcissus addressed the troops in Claudius’ stead

before the conquest of Britain. Since these were important positions, the

senators were aghast at their being placed in the hands of former slaves. If

freedmen had total control of money, letters, and law, it seemed it would not be

hard for them to manipulate the emperor. This is exactly the accusation put

forth by the ancient sources. However, these same sources admit that the

freedmen were loyal to Claudius.[26]

He was similarly appreciative of them and gave them due credit for policies

where he had used their advice. However, if they showed treasonous inclinations,

the emperor did punish them with just force, as in the case of Polybius and

Pallas’ brother,

Felix

. There is no evidence that the character of Claudius’ policies and

edicts changed with the rise and fall of the various freedmen, suggesting that

he was firmly in control throughout.

Regardless of the extent of their political power, the freedmen did manage to

amass wealth through their positions.

Pliny the Elder

notes that several of them were richer than

Crassus

, the richest man of the

Republican

era.[27]

Religious

reforms

Claudius, as the author of a treatise on Augustus’ religious reforms, felt

himself in a good position to institute some of his own. He had strong opinions

about the proper form for state religion. He refused the request of Alexandrian

Greeks to dedicate a temple to his divinity, saying that only gods may choose

new gods. He restored lost days to festivals and got rid of many extraneous

celebrations added by Caligula. He reinstituted old observances and archaic

language. Claudius was concerned with the spread of eastern mysteries within the

city and searched for more Roman replacements. He emphasized the

Eleusinian mysteries

which had been practiced by so many during the

Republic. He expelled foreign astrologers, and at the same time rehabilitated

the old Roman soothsayers (known as

haruspices

) as a replacement. He was especially hard on

Druidism

, because of its incompatibility with the Roman state religion and

its proselytizing

activities. It is also reported that at one time he expelled

the Jews from Rome, probably because the appearance of Christianity had caused

unrest within the Jewish community.[28]

Claudius opposed proselytizing in any religion, even in those regions where he

allowed natives to worship freely. The results of all these efforts were

recognized even by Seneca, who has an ancient Latin god defend Claudius in his

satire.[29]

Public

games and entertainments

According to Suetonius, Claudius was extraordinarily fond of games. He is

said to have risen with the crowd after gladiatorial matches and given

unrestrained praise to the fighters

[30]

.

Claudius also presided over many new and original events. Soon after coming into

power, Claudius instituted games to be held in honor of his father on the

latter’s birthday.[31].

Annual games were also held in honor of his accession, and took place at the

Praetorian camp where Claudius had first been proclaimed emperor.[32].

Claudius performed the

Secular games

, marking the 800th anniversary of the founding of Rome.

Augustus had performed the same games less than a century prior. Augustus’

excuse was that the interval for the games was 110 years, not 100, but his date

actually did not qualify under either reasoning.[32]

Claudius also presented naval battles to mark the attempted draining of the

Fucine lake, as well as many other public games and shows.

At Ostia, in front of a crowd of spectators, Claudius fought a

killer whale

which was trapped in the harbor. The event was witnessed by

Pliny the Elder

:

A killer whale was actually seen in the harbor of Ostia, locked in

combat with the emperor Claudius. She had come when he was completing

the construction of the harbor, drawn there by the wreck of a ship

bringing leather hides from Gaul, and feeding there over a number of

days, had made a furrow in the shallows: the waves had raised up such a

mound of sand that she couldn’t turn around at all, and while she was

pursuing her banquet as the waves moved it shorewards, her back stuck up

out of the water like the overturned keel of a boat. The emperor ordered

that a large array of nets be stretched across the mouths of the harbor,

and setting out in person with the

Praetorian

cohorts gave a show to the Roman people, soldiers

showering lances from attacking ships, one of which I saw swamped by the

beast’s waterspout and sunk. — “Historia Naturalis” IX.14-15.[33]

Claudius also restored and adorned many of the venues around Rome. The old

wooden barriers of the Circus Maximus were replaced with ones made of

gold-ornamented marble.[32]

A new section of the Circus was designated for seating the senators, who

previously had sat among the general public.[32]

Claudius rebuilt Pompey’s Theater after it had been destroyed by fire, throwing

special fights at the rededication which he observed from a special platform in

the orchestra box.[32]

Death,

deification, and reputation

The general consensus of ancient historians was that Claudius was murdered by

poison — possibly contained in mushrooms or on a feather — and died in the early

hours of 13 October, AD 54. Accounts vary greatly. Some claim Claudius was in

Rome[34]

while others claim he was in Sinuessa.[35]

Some implicate either

Halotus

, his

taster,

Xenophon

, his doctor, or the infamous poisoner

Locusta

as

the administrator of the fatal substance.[36]

Some say he died after prolonged suffering following a single dose at dinner,

and some have him recovering only to be poisoned again.[34]

Nearly all implicate his final wife, Agrippina, as the instigator. Agrippina and

Claudius had become more combative in the months leading up to his death. This

carried on to the point where Claudius openly lamented his bad wives, and began

to comment on Britannicus’ approaching manhood with an eye towards restoring his

status within the imperial family.[37]

Agrippina had motive in ensuring the succession of Nero before Britannicus could

gain power.

In modern times, some authors have cast doubt on whether Claudius was

murdered or merely succumbed to illness or old age.[38]

Some modern scholars claim the universality of the accusations in ancient texts

lends credence to the crime.[39]

History in those days could not be objectively collected or written, so

sometimes amounted to committing whispered gossip to parchment, often years

after the events, when the writer was no longer in danger of arrest. Claudius’

ashes were interred in the

Mausoleum of Augustus

on 24 October, after a funeral in the manner of

Augustus.

Claudius was deified by Nero and the Senate almost immediately.[40]

Those who regard this homage as cynical should note that, cynical or not, such a

move would hardly have benefited those involved, had Claudius been “hated”, as

some commentators, both modern and historic, characterize him. Many of Claudius’

less solid supporters quickly became Nero’s men. Claudius’ will had been changed

shortly before his death to either recommend Nero and Britannicus jointly or

perhaps just Britannicus, who would have been considered an adult man according

to Roman law only in a few months.

Agrippina had sent away Narcissus shortly before Claudius’ death, and now

murdered the freedman. The last act of this secretary of letters was to burn all

of Claudius’ correspondence—most likely so it could not be used against him and

others in an already hostile new regime. Thus Claudius’ private words about his

own policies and motives were lost to history. Just as Claudius has criticized

his predecessors in official edicts (see below), Nero often criticized the

deceased emperor and many of Claudius’ laws and edicts were disregarded under

the reasoning that he was too stupid and senile to have meant them.[41]

This opinion of Claudius, that he was indeed an old idiot, remained the official

one for the duration of Nero’s reign. Eventually Nero stopped referring to his

deified adoptive father at all, and realigned with his birth family. Claudius’

temple was left unfinished after only some of the foundation had been laid down.

Eventually the site was overtaken by Nero’s Golden House.[42]

The

Flavians

, who had risen to prominence under Claudius, took a different tack.

They were in a position where they needed to shore up their legitimacy, but also

justify the fall of the Julio-Claudians. They reached back to Claudius in

contrast with Nero, to show that they were good associated with good.

Commemorative coins were issued of Claudius and his son Britannicus—who had been

a friend of the emperor

Titus

. When

Nero’s Golden House was burned, the Temple of Claudius was finally completed on

Caelian Hill.[42]

However, as the Flavians became established, they needed to emphasize their own

credentials more, and their references to Claudius ceased. Instead, he was put

down with the other emperors of the fallen dynasty.

The main ancient historians

Tacitus

,

Suetonius

, and

Cassius

Dio

all wrote after the last of the Flavians had gone. All three were

senators or equites. They took the side of the Senate in most conflicts

with the princeps, invariably viewing him as being in the wrong. This resulted

in biases, both conscious and unconscious. Suetonius lost access to the official

archives shortly after beginning his work. He was forced to rely on second-hand

accounts when it came to Claudius (with the exception of Augustus’ letters which

had been gathered earlier) and does not quote the emperor. Suetonius painted

Claudius as a ridiculous figure, belittling many of his acts and attributing the

objectively good works to his retinue.[43]

Tacitus wrote a narrative for his fellow senators and fitted each of the

emperors into a simple mold of his choosing.[44]

He wrote Claudius as a passive pawn and an idiot—going so far as to hide his use

of Claudius as a source and omit Claudius’ character from his works.[45]

Even his version of Claudius’ Lyons tablet speech is edited to be devoid of the

emperor’s personality. Dio was less biased, but seems to have used Suetonius and

Tacitus as sources. Thus the conception of Claudius as the weak fool, controlled

by those he supposedly ruled, was preserved for the ages.

As time passed, Claudius was mostly forgotten outside of the historians’

accounts. His books were lost first, as their antiquarian subjects became

unfashionable. In the second century,

Pertinax

,

who shared his birthday, became emperor, overshadowing commemoration of

Claudius.[46]

Marriages

and personal life

Claudius’ love life was unusual for an upper-class Roman of his day. As

Edward Gibbon

mentions, of the first fifteen emperors, “Claudius was the

only one whose taste in love was entirely correct”—the implication being that he

was the only one not to take

men

or boys

as lovers. Gibbon based this on Suetonius’ factual statement that “He had a

great passion for women, but had no interest in men.”[47]

Suetonius and the other ancient authors used this against Claudius. They accused

him of being dominated by these same women and wives, of being

uxorious

, and of being a

womanizer

.

Claudius married four times. His first marriage, to

Plautia Urgulanilla

, occurred after two failed betrothals (The first was to

his distant cousin

Aemilia Lepida

, but was broken for political reasons. The second was to

Livia Medullina

, which ended with the bride’s sudden death on their wedding

day). Urgulanilla was a relation of Livia’s confidant

Urgulania

.

During their marriage she gave birth to a son, Claudius Drusus. Unfortunately,

Drusus died of asphyxiation in his early teens, shortly after becoming engaged

to the daughter of

Sejanus

.

Claudius later divorced Urgulanilla for adultery and on suspicion of murdering

her sister-in-law Apronia. When Urgulanilla gave birth after the divorce,

Claudius repudiated the baby girl, Claudia, as the father was one of his own

freedmen. Soon after (possibly in AD 28), Claudius married

Aelia

Paetina

, a relation of Sejanus. They had a daughter,

Claudia Antonia

. He later divorced her after the marriage became a political

liability (although Leon (1948) suggests it may have been due to emotional and

mental abuse by Aelia).

In AD 38 or early 39, Claudius married

Valeria Messalina

, who was his first cousin once removed and closely allied

with Caligula’s circle. Shortly thereafter, she gave birth to a daughter

Claudia Octavia

. A son, first named Tiberius Claudius Germanicus, and later

known as Britannicus

, was born just after Claudius’ accession. This marriage ended in

tragedy. The ancient historians allege that Messalina was a

nymphomaniac

who was regularly unfaithful to Claudius —

Tacitus

states she went so far as to compete with a

prostitute

to see who could have the most sexual partners in a night[48]

— and manipulated his policies in order to amass wealth. In AD 48, Messalina

married her lover

Gaius

Silius

in a public ceremony while Claudius was at

Ostia

. Sources disagree as to whether or not she divorced the emperor first,

and whether the intention was to usurp the throne. Scramuzza, in his biography,

suggests that Silius may have convinced Messalina that Claudius was doomed, and

the union was her only hope of retaining rank and protecting her children.[49]

The historian Tacitus

suggests that Claudius’s ongoing term as Censor may have prevented

him from noticing the affair before it reached such a critical point.[50]

Whatever the case, the result was the execution of Silius, Messalina, and most

of her circle.[51]

Claudius made the

Praetorians

promise to kill him if he ever married again.

Despite this declaration, Claudius did marry once more. The ancient sources

tell that his freedmen pushed three candidates, Caligula’s former wife

Lollia Paulina

, Claudius’s divorced second wife Aelia, and Claudius’s niece

Agrippina the younger

. According to Suetonius, Agrippina won out through her

feminine wiles.[52]

The truth is likely more political. The

coup

attempt by Silius probably made Claudius realize the weakness of his

position as a member of the Claudian but not the Julian family. This weakness

was compounded by the fact that he did not have an obvious adult heir,

Britannicus being just a boy. Agrippina was one of the few remaining descendants

of Augustus, and her son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (later known as

Nero) was one of

the last males of the imperial family. Future coup attempts could rally around

the pair, and Agrippina was already showing such ambition. It has been suggested

in recent times that the Senate may have pushed for the marriage to end the feud

between the Julian and Claudian branches.[53]

This feud dated back to Agrippina’s

mother’s

actions against Tiberius after the death of her husband Germanicus,

actions which Tiberius had gladly punished. In any case, Claudius accepted

Agrippina, and later adopted the newly mature Nero as his son.

Nero was made joint heir with the underage Britannicus, married to Octavia

and heavily promoted. This was not as unusual as it seems to people acquainted

with modern hereditary monarchies.

Barbara Levick

notes that Augustus had named his grandson

Postumus Agrippa

and his stepson Tiberius joint heirs.[54]

Tiberius named his great-nephew Caligula joint heir with his grandson

Tiberius Gemellus

. Adoption of adults or near adults was an old tradition in

Rome when a suitable natural adult heir was unavailable. This was the case

during Britannicus’ minority. S.V. Oost suggests that Claudius had previously

looked to adopt one of his sons-in-law to protect his own reign.[55]

Faustus Sulla

, married to his daughter

Antonia

, was only descended from Octavia and Antony on one side — not close

enough to the imperial family to prevent doubts (that didn’t stop others from

making him the object of a coup attempt against Nero a few years later). Besides

which, he was the half brother of

Messalina

, and at this time those wounds were still fresh.

Nero was more

popular with the general public as the grandson of Germanicus and the direct

descendant of Augustus.

Claudius’

affliction and personality

The historian

Suetonius

describes the physical manifestations of Claudius’ affliction in

relatively good detail.[56]

His knees were weak and gave way under him and his head shook. He stammered and

his speech was confused. He slobbered and his nose ran when he was excited. The

Stoic

Seneca

states in his

Apocolocyntosis

that Claudius’ voice belonged to no land animal, and

that his hands were weak as well;[57]

however, he showed no physical deformity, as Suetonius notes that when calm and

seated he was a tall, well-built figure of

dignitas

.[56]

When angered or stressed, his symptoms became worse. Historians agree that this

condition improved upon his accession to the throne.[58]

Claudius himself claimed that he had exaggerated his ailments to save his own

life.[59]

The modern diagnosis has changed several times in the past century. Prior to

World

War II

,

infantile paralysis

(or polio) was widely accepted as the cause. This is the

diagnosis used in

Robert Graves

‘

Claudius novels

, first published in the 1930s. Polio does not explain many

of the described symptoms, however, and a more recent theory implicates

cerebral palsy

as the cause, as outlined by Ernestine Leon.[60]

Tourette syndrome

is also a likely candidate for Claudius’ symptoms.[61]

As a person, ancient historians described Claudius as generous and lowbrow, a

man who sometimes lunched with the

plebeians

.[62]

They also paint him as bloodthirsty and cruel, overly fond of both

gladiatorial

combat and executions, and very quick to anger (though Claudius himself

acknowledged the latter trait, and apologized publicly for his temper).[63]

To them he was also overly trusting, and easily manipulated by his wives and

freedmen.[64]

But at the same time they portray him as paranoid and apathetic, dull and easily

confused.[65]

The extant works of Claudius present a different view, painting a picture of an

intelligent, scholarly, well-read, and conscientious administrator with an eye

to detail and justice. Thus, Claudius becomes an enigma. Since the discovery of

his “Letter

to the Alexandrians” in the last century, much work has been done to

rehabilitate Claudius and determine where the truth lies.

Scholarly

works and their impact

Claudius wrote copiously throughout his life.

Arnaldo Momigliano

[66]

states that during the reign of Tiberius — which covers the peak of Claudius’

literary career — it became impolitic to speak of republican Rome. The trend

among the young historians was to either write about the new empire or obscure

antiquarian subjects. Claudius was the rare scholar who covered both. Besides

the history of Augustus’ reign that caused him so much grief, his major works

included an

Etruscan

history and eight volumes on

Carthaginian

history, as well as an Etruscan Dictionary and a book on dice playing. Despite

the general avoidance of the imperatorial era, he penned a defense of

Cicero

against

the charges of Asinius Gallus. Modern historians have used this to determine

both the nature of his politics and of the aborted chapters of his civil war

history. He proposed a reform of the

Latin alphabet

by the addition of

three new letters

, two of which served the function of the modern letters

W and Y. He officially instituted the change during his censorship,

but they did not survive his reign. Claudius also tried to revive the old custom

of putting dots between different words (Classical Latin was written with no

spacing). Finally, he wrote an eight-volume autobiography that Suetonius

describes as lacking in taste.[67]

Since Claudius (like most of the members of his dynasty) heavily criticized his

predecessors and relatives in surviving speeches,[68]

it is not hard to imagine the nature of Suetonius’ charge.

Unfortunately, none of the actual works survive. They do live on as sources

for the surviving histories of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Suetonius quotes

Claudius’ autobiography once, and must have used it as a source numerous times.

Tacitus uses Claudius’ own arguments for the orthographical innovations

mentioned above, and may have used him for some of the more antiquarian passages

in his annals. Claudius is the source for numerous passages of

Pliny’s

Natural History

.[69]

The influence of historical study on Claudius is obvious. In his speech on

Gallic senators, he uses a version of the founding of Rome identical to that of

Livy, his tutor in adolescence. The detail of his speech borders on the

pedantic, a common mark of all his extant works, and he goes into long

digressions on related matters. This indicates a deep knowledge of a variety of

historical subjects that he could not help but share. Many of the public works

instituted in his reign were based on plans first suggested by

Julius Caesar

. Levick believes this emulation of Caesar may have spread to

all aspects of his policies.[70]

His censorship seems to have been based on those of his ancestors, particularly

Appius Claudius Caecus

, and he used the office to put into place many

policies based on those of Republican times. This is when many of his religious

reforms took effect and his building efforts greatly increased during his

tenure. In fact, his assumption of the office of Censor may have been motivated

by a desire to see his academic labors bear fruit. For example, he believed (as

most Romans) that his ancestor Appius Claudius Caecus had used the censorship to

introduce the letter “R”

[71]

and so used his own term to introduce his new letters.

In

literature and film

Probably the most famous fictional representation of the Emperor Claudius

were the books

I, Claudius

and

Claudius the God

(released in 1934 and 1935) by

Robert Graves

, both written in the

first-person

to give the reader the impression that they are Claudius’

autobiography

. Graves employed a fictive artifice to suggest that they were

recently discovered, genuine translations of Claudius’ writings. Claudius’

extant letters, speeches, and sayings were incorporated into the text (mostly in

the second book, Claudius the God) in order to add authenticity.

In 1937 director

Josef von Sternberg

made an unsuccessful attempt to film

I, Claudius

, with

Charles Laughton

as Claudius. Unfortunately, the lead actress

Merle

Oberon

suffered a near-fatal accident and the movie was never finished. The

surviving reels were finally shown in the documentary The Epic That Never Was

in 1965, revealing some of Laughton’s most accomplished acting. The motion

picture rights have been obtained by

Scott

Rudin

, with a theatrical release planned for 2010.

Graves’s two books were also the basis for a

thirteen-part British television adaptation

produced by the

BBC

. The series starred

Derek

Jacobi

as Claudius and

Patrick Stewart

as Sejanus, and was broadcast in 1976 on

BBC2

. It was

a substantial critical success, and won several

BAFTA

awards. The series was later broadcast in the

United States

on

Masterpiece Theatre

in 1977. The DVD release of the television series

contains the “The Epic that Never Was” documentary.

Claudius has been portrayed in film on several other occasions, including in

the 1979 motion picture

Caligula

, the role being performed by

Giancarlo Badessi

in which the character was depicted as an idiot, in

complete contrast to

Robert Graves

‘ portrait of Claudius as a cunning and deeply intelligent man.

In the parody

Gore Vidal’s Caligula

, which advertises itself as a remake of the

original film, Claudius is portrayed by

Glenn

Shadix

.

On television, the actor

Freddie Jones

became famous for his role as Claudius in the 1968 British

television

series The Caesars while the 1985 made-for-television

miniseries

A.D. features actor

Richard Kiley

as Claudius. There is also a reference to Claudius’

suppression of one of the coups against him in the movie

Gladiator

, though the incident is entirely fictional.

In literature, Claudius and his contemporaries appear in the historical novel

The Roman by

Mika

Waltari

. Canadian-born science fiction writer

A.

E. van Vogt

reimagined Robert Graves’ Claudius story in his two novels

Empire of the Atom and The Wizard of Linn.

Ancestry

|

|

|

|

|

8.

Drusus Claudius Nero

|

|

|

|

|

4.

Tiberius Nero

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. Unknown |

|

|

|

|

2.

Nero Claudius Drusus

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10.

Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus

|

|

|

|

|

5. Livia

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11. Aufidia

And Clasuia |

|

|

|

1.Claudius |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12.

Marcus Antonius Creticus

|

|

|

|

|

6.

Mark Antony

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13.

Julia Antonia

|

|

|

|

|

3.

Antonia Minor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14.

Gaius Octavius

|

|

|

|

|

7.

Octavia Minor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15.

Atia Balba Caesonia

|

|

|

|

_01.jpg/250px-Claudius_(M.A.N._Madrid)_01.jpg) Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (1 August 10 BC – 13

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (1 August 10 BC – 13