Modern-era

|

|

Commodus (Latin:

Marcus Aurelius Commodus Antoninus Augustus;

31 August, 161 AD – 31 December, 192 AD), was

Roman Emperor

from 180 to 192. He also ruled as

co-emperor with his father

Marcus Aurelius

from 177 until his father’s

death in 180.

His accession as emperor was the first time a son had succeeded his father

since Titus

succeeded

Vespasian

in 79. He was also the first Emperor

to have both a father and grandfather as the two preceding Emperors. Commodus

was the first (and until 337 the only) emperor “born

in the purple“; i.e. during his father’s reign.

Commodus was assassinated in 192.

Early life and rise to power (161–180)

Early life

Commodus was born on 31 August 161, as Commodus, in

Lanuvium

, near

Rome

. He was the son of the reigning emperor,

Marcus Aurelius, and Aurelius’s first cousin, Faustina the Younger; the youngest

daughter of

Roman Emperor

Antonius Pius

. Commodus had an elder twin

brother, Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, who died in 165. On 12 October 166,

Commodus was made

Caesar

together with his younger brother,

Marcus Annius Verus

. The latter died in 169

having failed to recover from an operation, which left Commodus as Marcus

Aurelius’ sole surviving son.

He was looked after by his father’s physician,

Galen

, in order to keep Commodus healthy and

alive. Galen treated many of Commodus’ common illnesses. Commodus received

extensive tuition at the hands of what Marcus Aurelius called “an abundance of

good masters.” The focus of Commodus’ education appears to have been

intellectual, possibly at the expense of military training.

Commodus is known to have been at

Carnuntum

, the headquarters of Marcus Aurelius

during the

Marcomannic Wars

, in 172. It was presumably

there that, on 15 October 172, he was given the victory title Germanicus,

in the presence of the

army

. The title suggests that Commodus was

present at his father’s victory over the

Marcomanni

. On 20 January 175, Commodus entered

the

College of Pontiffs

, the starting point of a

career in public life.

In April 175,

Avidius Cassius

, Governor of

Syria

, declared himself Emperor following

rumors that Marcus Aurelius had died. Having been accepted as Emperor by Syria,

Palestine

and

Egypt

, Cassius carried on his rebellion even

after it had become obvious that Marcus was still alive. During the preparations

for the campaign against Cassius, the Prince assumed his

toga virilis

on the

Danubian

front on 7 July 175, thus formally

entering

adulthood

. Cassius, however, was killed by one

of his centurions

before the campaign against him

could begin.

Commodus subsequently accompanied his father on a lengthy trip to the Eastern

provinces, during which he visited

Antioch

. The Emperor and his son then traveled

to Athens

, where they were initiated into the

Eleusinian mysteries

. They then returned to

Rome in the Autumn

of 176.

Joint rule

with father (177)

Marcus Aurelius was the first emperor since

Vespasian

to have a biological son of his own

and, though he himself was the fifth in the line of the so-called

Five Good Emperors

, each of whom had adopted

his successor, it seems to have been his firm intention that Commodus should be

his heir. On 27 November 176, Marcus Aurelius granted Commodus the rank of

Imperator

and, in the middle of 177, the

title

Augustus

, giving his son the same status as

his own and formally sharing power.

On 23 December of the same year, the two Augusti celebrated a joint

triumph

, and Commodus was given

tribunician

power. On 1 January 177, Commodus

became consul

for the first time, which made him, aged

15, the youngest consul in Roman history up to that time. He subsequently

married

Bruttia Crispina

before accompanying his father

to the Danubian front once more in 178, where Marcus Aurelius died on 17 March

180, leaving the 18-year-old Commodus sole emperor.

Sole reign

(180–192)

Upon his accession Commodus devalued the

Roman currency

. He reduced the weight of the

denarius

from 96 per

Roman pound

to 105 (3.85 grams to 3.35 grams).

He also reduced the silver purity from 79 percent to 76 percent – the silver

weight dropping from 2.57 grams to 2.34 grams. In 186 he further reduced the

purity and silver weight to 74 percent and 2.22 grams respectively, being 108 to

the Roman pound.

His reduction of the denarius during his rule was the largest since the empire’s

first devaluation during

Nero‘s reign.

Whereas the reign of

Marcus Aurelius

had been marked by almost

continuous warfare, that of Commodus was comparatively peaceful in the military

sense but was marked by political strife and the increasingly arbitrary and

capricious behaviour of the emperor himself. In the view of

Dio Cassius

, a contemporary observer, his

accession marked the descent “from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron” –

a famous comment which has led some historians, notably

Edward Gibbon

, to take Commodus’s reign as the

beginning of the

decline of the Roman Empire

.

Despite his notoriety, and considering the importance of his reign,

Commodus’s years in power are not well chronicled. The principal surviving

literary sources are Dio Cassius (a contemporary and sometimes first-hand

observer, but for this reign, only transmitted in fragments and abbreviations),

Herodian

and the

Historia Augusta

(untrustworthy for its

character as a work of literature rather than history, with elements of fiction

embedded within its biographies; in the case of Commodus, it may well be

embroidering upon what the author found in reasonably good contemporary

sources).

Commodus remained with the Danube armies for only a short time before

negotiating a peace treaty with the Danubian tribes. He then returned to Rome

and celebrated a triumph for the conclusion of the wars on 22 October 180.

Unlike the preceding Emperors

Trajan

,

Hadrian

,

Antoninus Pius

and Marcus Aurelius, he seems to

have had little interest in the business of administration and tended throughout

his reign to leave the practical running of the state to a succession of

favourites, beginning with

Saoterus

, a freedman from

Nicomedia

who had become his

chamberlain

.

Dissatisfaction with this state of affairs would lead to a series of

conspiracies and attempted coups, which in turn eventually provoked Commodus to

take charge of affairs, which he did in an increasingly dictatorial manner.

Nevertheless, though the

senatorial order

came to hate and fear him, the

evidence suggests that he remained popular with the army and the common people

for much of his reign, not least because of his lavish shows of largesse

(recorded on his coinage) and because he staged and took part in spectacular

gladiatorial

combats.

One of the ways he paid for his donatives and mass entertainments was to tax

the senatorial order, and on many inscriptions, the traditional order of the two

nominal powers of the state, the Senate and People (Senatus Populusque

Romanus) is provocatively reversed (Populus Senatusque…).

The conspiracies of

182

Museum, Cologne).

At the outset of his reign, Commodus, age 18, inherited many of his father’s

senior advisers, notably

Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus

(the second

husband of Commodus’s sister

Lucilla

), his father-in-law

Gaius Bruttius Praesens

, Titus Fundanius

Vitrasius Pollio, and

Aufidius Victorinus

, who was

Prefect of the City of Rome

. He also had five

surviving sisters, all of them with husbands who were potential rivals. Four of

his sisters were considerably older than he; the eldest, Lucilla, held the rank

of

Augusta

as the widow of her first husband,

Lucius Verus

.

The first crisis of the reign came in 182, when Lucilla engineered a

conspiracy against her brother. Her motive is alleged to have been envy of the

Empress

Crispina. Her husband, Pompeianus, was

not involved, but two men alleged to have been her lovers,

Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus

(the consul

of 167, who was also her first cousin) and

Appius Claudius Quintianus

, attempted to murder

Commodus as he entered the theatre. They bungled the job and were seized by the

emperor’s bodyguard.

Quadratus and Quintianus were executed. Lucilla was exiled to

Capri

and later killed. Pompeianus retired from

public life. One of the two

praetorian prefects

,

Tarrutenius Paternus

, had actually been

involved in the conspiracy but was not detected at this time, and in the

aftermath, he and his colleague

Sextus Tigidius Perennis

were able to arrange

for the murder of Saoterus, the hated chamberlain.

Commodus took the loss of Saoterus badly, and Perennis now seized the chance

to advance himself by implicating Paternus in a second conspiracy, one

apparently led by

Publius Salvius Julianus

, who was the son of

the jurist

Salvius Julianus

and was betrothed to

Paternus’s daughter. Salvius and Paternus were executed along with a number of

other prominent consulars and senators.

Didius Julianus

, the future emperor, a relative

of Salvius Julianus, was dismissed from the governorship of

Germania Inferior

.

Cleander

Perennis took over the reins of government and Commodus found a new

chamberlain and favourite in

Cleander

, a

Phrygian

freedman

who had married one of the emperor’s

mistresses, Demostratia. Cleander was in fact the person who had murdered

Saoterus. After those attempts on his life, Commodus spent much of his time

outside Rome, mostly on the family estates at Lanuvium. Being physically strong,

his chief interest was in sport: taking part in

horse racing

,

chariot racing

, and combats with beasts and

men, mostly in private but also on occasion in public.

Dacia and Britain

Museum, Vienna). According to

Herodian

he was well proportioned

and attractive, with naturally blonde and curly hair.

Commodus was inaugurated in 183 as consul with Aufidius Victorinus for a

colleague and assumed the title

Pius. War broke out in

Dacia

: few details are available, but it

appears two future contenders for the throne,

Clodius Albinus

and

Pescennius Niger

, both distinguished themselves

in the campaign. Also, in

Britain

in 184, the governor

Ulpius Marcellus

re-advanced the Roman frontier

northward to the

Antonine Wall

, but the

legionaries

revolted against his harsh

discipline and acclaimed another legate, Priscus, as emperor.

Priscus refused to accept their acclamations, but Perennis had all the

legionary legates

in Britain

cashiered

. On 15 October 184 at the

Capitoline Games

, a

Cynic

philosopher publicly denounced Perennis

before Commodus, who was watching, but was immediately put to death. According

to Dio Cassius, Perennis, though ruthless and ambitious, was not personally

corrupt and generally administered the state well.

However, the following year, a detachment of soldiers from Britain (they had

been drafted to

Italy

to suppress brigands) also denounced

Perennis to the emperor as plotting to make his own son emperor (they had been

enabled to do so by Cleander, who was seeking to dispose of his rival), and

Commodus gave them permission to execute him as well as his wife and sons. The

fall of Perennis brought a new spate of executions: Aufidius Victorinus

committed suicide. Ulpius Marcellus was replaced as

governor of Britain

by

Pertinax

; brought to Rome and tried for

treason, Marcellus narrowly escaped death.

Cleander’s zenith and fall (185–190)

Cleander proceeded to concentrate power in his own hands and to enrich

himself by becoming responsible for all public offices: he sold and bestowed

entry to the Senate, army commands,

governorships

and, increasingly, even the

suffect consulships

to the highest bidder.

Unrest around the empire increased, with large numbers of army deserters causing

trouble in Gaul

and

Germany

. Pescennius Niger mopped up the

deserters in Gaul in a military campaign, and a revolt in

Brittany

was put down by two

legions

brought over from Britain.

In 187, one of the leaders of the deserters, Maternus, came from Gaul

intending to assassinate Commodus at the Festival of the Great Goddess in March,

but he was betrayed and executed. In the same year,

Pertinax

unmasked a conspiracy by two enemies

of Cleander – Antistius Burrus (one of Commodus’s brothers-in-law) and Arrius

Antoninus. As a result, Commodus appeared even more rarely in public, preferring

to live on his estates.

Early in 188, Cleander disposed of the current praetorian prefect,

Atilius Aebutianus

, and himself took over

supreme command of the Praetorians at the new rank of a pugione

(“dagger-bearer”) with two praetorian prefects subordinate to him. Now at the

zenith of his power, Cleander continued to sell public offices as his private

business. The climax came in the year 190, which had 25 suffect consuls – a

record in the 1000-year history of the Roman consulship—all appointed by

Cleander (they included the future Emperor

Septimius Severus

).

In the spring of 190, Rome was afflicted by a food shortage, for which the

praefectus annonae

Papirius Dionysius

, the official actually in

charge of the

grain supply

, contrived to lay the blame on

Cleander. At the end of June, a mob demonstrated against Cleander during a horse

race in the

Circus Maximus

: he sent the praetorian guard to

put down the disturbances, but Pertinax, who was now City Prefect of Rome,

dispatched the

Vigiles Urbani

to oppose them. Cleander

fled to Commodus, who was at

Laurentum

in the house of the

Quinctilii

, for protection, but the mob

followed him calling for his head.

At the urging of his mistress

Marcia

, Commodus had Cleander beheaded and his

son killed. Other victims at this time were the praetorian prefect Julius

Julianus, Commodus’s cousin

Annia Fundania Faustina

, and his brother-in-law

Mamertinus. Papirius Dionysius was executed too.

The emperor now changed his name to Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus. At 29,

he took over more of the reins of power, though he continued to rule through a

cabal consisting of Marcia, his new chamberlain Eclectus, and the new praetorian

prefect

Quintus Aemilius Laetus

, who about this time

also had many Christians freed from working in the mines in

Sardinia

. Marcia, the widow of Quadratus, who

had been executed in 182, is alleged to have been a Christian.

Megalomania

(190–192)

In opposition to the Senate, in his pronouncements and

iconography

, Commodus had always laid stress on

his unique status as a source of god-like power, liberality and physical

prowess. Innumerable statues around the empire were set up portraying him in the

guise of Hercules

, reinforcing the image of him as a

demigod, a physical giant, a protector and a battler against beasts and men (see

“Commodus and Hercules” and “Commodus the Gladiator” below). Moreover, as

Hercules, he could claim to be the son of

Jupiter

, the representative of the supreme god

of the Roman

pantheon

. These tendencies now increased to

megalomaniac

proportions. Far from celebrating

his descent from Marcus Aurelius, the actual source of his power, he stressed

his own personal uniqueness as the bringer of a new order, seeking to re-cast

the empire in his own image.

During 191, the city of Rome was extensively damaged by a fire that raged for

several days, during which many public buildings including the

Temple of Pax

, the

Temple of Vesta

and parts of the imperial

palace were destroyed.

Perhaps seeing this as an opportunity, early in 192 Commodus, declaring

himself the new

Romulus

, ritually re-founded Rome, renaming the

city Colonia Lucia Annia Commodiana. All the months of the year were

renamed to correspond exactly with his (now twelve) names: Lucius,

Aelius, Aurelius, Commodus, Augustus, Herculeus,

Romanus, Exsuperatorius, Amazonius, Invictus,

Felix, Pius. The legions were renamed Commodianae, the fleet

which imported grain from

Africa

was termed Alexandria Commodiana

Togata, the Senate was entitled the Commodian Fortunate Senate, his palace

and the Roman people themselves were all given the name Commodianus, and

the day on which these reforms were decreed was to be called Dies Commodianus.

Thus he presented himself as the fountainhead of the Empire and Roman life

and religion. He also had the head of the

Colossus of Nero

adjacent to the

Colosseum

replaced with his own portrait, gave

it a club and placed a

bronze

lion at its feet to make it look like Hercules, and added an

inscription boasting of being “the only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve

times one thousand men”.

Character and

physical prowess

Character and

motivations

Dio Cassius, a first-hand witness, describes him as “not naturally wicked

but, on the contrary, as guileless as any man that ever lived. His great

simplicity, however, together with his cowardice, made him the slave of his

companions, and it was through them that he at first, out of ignorance, missed

the better life and then was led on into lustful and cruel habits, which soon

became second nature.”[8]

His recorded actions do tend to show a rejection of his father’s policies,

his father’s advisers, and especially his father’s austere lifestyle, and an

alienation from the surviving members of his family. It seems likely that he was

brought up in an atmosphere of

Stoic

asceticism

, which he rejected entirely upon his

accession to sole rule. After repeated attempts on Commodus’ life,

Roman citizens

were often killed for raising

his ire. One such notable event was the attempted extermination of the house of

the Quinctilii. Condianus and Maximus were executed on the pretext that, while

they were not implicated in any plots, their wealth and talent would make them

unhappy with the current state of affairs.

Changes of name

On his accession as sole ruler, Commodus added the name Antoninus to his

official nomenclature. In October 180 he changed his

praenomen

from Lucius to Marcus, presumably

in honour of his father. He later took the title of Felix in 185. In 191

he restored his praenomen to Lucius and added the family name Aelius,

apparently linking himself to Hadrian and Hadrian’s adopted son

Lucius Aelius Caesar

, whose original name was

also Commodus.

Later that year he dropped Antoninus and adopted as his full style Lucius

Aelius Aurelius Commodus Augustus Herculeus Romanus Exsuperatorius Amazonius

Invictus Felix Pius (the order of some of these titles varies in the sources). “Exsuperatorius”

(the supreme) was a title given to Jupiter, and “Amazonius” identified him again

with Hercules.

An inscribed altar from

Dura-Europos

on the Euphrates shows that

Commodus’s titles and the renaming of the months were disseminated to the

furthest reaches of the Empire; moreover, that even auxiliary military units

received the title Commodiana, and that Commodus claimed two additional titles:

Pacator Orbis (pacifier of the world) and Dominus Noster (Our

Lord). The latter eventually would be used as a conventional title by Roman

emperors, starting about a century later, but Commodus seems to have been the

first to assume it.

Commodus and Hercules

Disdaining the more philosophic inclinations of his father, Commodus was

extremely proud of his physical prowess. He was generally acknowledged to be

extremely handsome. As mentioned above, he ordered many statues to be made

showing him dressed as Hercules with a lion’s hide and a club. He thought of

himself as the reincarnation of Hercules, frequently emulating the legendary

hero’s feats by appearing in the arena to fight a variety of wild animals. He

was left-handed, and very proud of the fact. Cassius Dio and the writers of the

Augustan History

say that Commodus was a

skilled archer, who could shoot the heads off

ostriches

in full gallop, and kill a

panther

as it attacked a victim in the arena.

Commodus the gladiator

Commodus also had a passion for gladiatorial combat, which he took so far as

to take to the arena

himself, dressed as a gladiator. The

Romans found Commodus’s naked gladiatorial combats to be scandalous and

disgraceful.

It was rumoured that he was actually the son, not of Marcus Aurelius, but of a

gladiator whom his mother Faustina had taken as a lover at the coastal resort of

Caieta

.

In the arena, Commodus always won since his opponents always submitted to the

emperor. Thus, these public fights would not end in death. Privately, it was his

custom to slay his practice opponents.

For each appearance in the arena, he charged the city of Rome a million

sesterces

, straining the Roman economy.

Commodus raised the ire of many military officials in Rome for his Hercules

persona in the arena. Often, wounded soldiers and amputees would be placed in

the arena for Commodus to slay with a sword. Commodus’s eccentric behaviour

would not stop there. Citizens of Rome missing their feet through accident or

illness were taken to the arena, where they were tethered together for Commodus

to club to death while pretending they were giants.

These acts may have contributed to his assassination.

Commodus was also known for fighting exotic animals in the arena, often to

the horror of the Roman people. According to Gibbon, Commodus once killed 100

lions in a single day.

Later, he decapitated a running ostrich with a specially designed dart

and afterwards carried the bleeding head of the dead bird and his sword over to

the section where the Senators sat and gesticulated as though they were next.

On another occasion, Commodus killed three

elephants

on the floor of the arena by himself.

Finally, Commodus killed a

giraffe

, which was considered to be a strange

and helpless beast.

Assassination (192)

In November 192 Commodus held Plebian Games, in which he shot hundreds of

animals with arrows and javelins every morning, and fought as a gladiator every

afternoon, winning all the bouts. In December he announced his intention to

inaugurate the year 193 as both consul and gladiator on 1 January.

At this point, the prefect Laetus formed a conspiracy with Eclectus to

supplant Commodus with Pertinax, taking Marcia into their confidence. On 31

December Marcia poisoned his food but he vomited up the poison; so the

conspirators sent his wrestling partner

Narcissus

to strangle him in his bath. Upon his

death, the Senate declared him a public enemy (a de facto

damnatio memoriae

) and restored the

original name to the city of Rome and its institutions. Commodus’s statues were

thrown down. His body was buried in the

Mausoleum of Hadrian

. In 195 the emperor

Septimius Severus

, trying to gain favour with

the family of Marcus Aurelius, rehabilitated Commodus’s memory and had the

Senate deify him.

Commodus was succeeded by

Pertinax

, whose reign was short lived, being

the first to fall victim to the

Year of the Five Emperors

. Commodus’s death

marked the end of the

Nervan-Antonian dynasty

.

Head of a genius worshipped by Roman soldiers (found at

Vindobona

, 2nd century CE)

In

ancient Roman religion

, the genius was

the individual instance of a general divine nature that is present in every

individual person, place, or thing.

Winged genius facing a woman with a tambourine and mirror, from

southern Italy, about 320 BC.

Nature of the genius

The rational powers and abilities of every human being were attributed to

their soul, which was a genius. Each individual place had a genius

(genius

loci) and so did powerful objects, such as volcanoes. The concept

extended to some specifics: the genius of the theatre, of vineyards, and of

festivals, which made performances successful, grapes grow, and celebrations

succeed, respectively. It was extremely important in the Roman mind to

propitiate the appropriate genii for the major undertakings and events of their

lives.

Specific genii

Bronze genius depicted as

pater familias

(1st century CE)

Although the term genius might apply to any divinity whatsoever, most

of the higher-level and state genii had their own well-established names.

Genius applied most often to individual places or people not generally

known; that is, to the smallest units of society and settlements, families and

their homes. Houses, doors, gates, streets, districts, tribes, each one had its

own genius.The supreme hierarchy of the Roman gods, like that of the Greeks, was modelled

after a human family. It featured a father,

Jupiter

(“father god”), who, in a

patriarchal society

was also the supreme divine

unity, and a mother,

Juno

, queen of the gods. These supreme

unities were subdivided into genii for each individual family; hence, the

genius of each female, representing the female domestic reproductive

power, was a Juno. The male function was a Jupiter.

The juno was worshipped under many titles:

- Iugalis, “of marriage”

- Matronalis, “of married women”

- Pronuba, “of brides”

- Virginalis, “of virginity”

Genii were often viewed as protective spirits, as one would propitiate

them for protection. For example, to protect infants one propitiated a number of

deities concerned with birth and childrearing

:

Cuba (“lying down to sleep”), Cunina (“of the cradle”) and

Rumina (“of breast-feeding”).

Certainly, if those genii did not perform their proper function well, the

infant would be in danger.

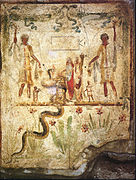

Hundreds of lararia, or family shrines, have been discovered at

Pompeii

, typically off the

atrium

, kitchen or garden, where the smoke

of burnt offerings could vent through the opening in the roof. A lararium

was distinct from the penus (“within”), another shrine where the

penates

, gods associated with the storerooms,

was located. Each lararium features a panel fresco containing the same

theme: two peripheral figures (Lares)

attend on a central figure (family genius) or two figures (genius

and Juno) who may or may not be at an altar. In the foreground is one or

two serpents crawling toward the genius through a meadow motif.

Campania

and

Calabria

preserved an ancient practice of

keeping a propitious house snake, here linked with the genius.

In another, unrelated fresco (House

of the Centenary) the snake-in-meadow appears below a depiction of

Mount Vesuvius

and is labelled Agathodaimon,

“good

daimon

“, where daimon must be regarded

as the Greek equivalent of genius.

History of the concept

Origin

Etymologically

genius

(“household guardian spirit”) has

the same derivation as nature from

gēns

(“tribe”, “people”) from the

Indo-European

root *gen-, “produce.”

It is the indwelling nature of an object or class of objects or events that act

with a perceived or hypothesized unity.

Philosophically the Romans did not find the paradox of the one being many

confusing; like all other prodigies they attributed it to the inexplicable

mystery of divinity. Multiple events could therefore be attributed to the same

and different divinities and a person could be the same as and different from

his genius. They were not distinct, as the later guardian angels, and yet

the Genius Augusti was not exactly the same as Augustus either. As

a natural outcome of these beliefs, the pleasantness of a place, the strength of

an oath, an ability of a person, were regarded as intrinsic to the object, and

yet were all attributable to genius; hence all of the modern meanings of

the word. This point of view is not attributable to any one civilization; its

roots are lost in prehistory. The Etruscans had such beliefs at the beginning of

history, but then so did the Greeks, the native Italics and many other peoples

in the near and middle east.

Genii under the

monarchy

No literature of the monarchy has survived, but later authors in recounting

its legends mention the genius. For example, under

Servius Tullius

the triplets

Horatii

of Rome fought the triplets Curiatii of

Alba Longa

for the decision of the war that had

arisen between the two communities. Horatius was left standing but his sister,

who had been betrothed to one of the Curiatii, began to keen, breast-beat and

berate Horatius. He executed her, was tried for murder, was acquitted by the

Roman people but the king made him expiate the Juno of his sister and the

Genius Curiatii, a family genius.

Republican genii

The genius appears explicitly in Roman literature relatively late as

early as Plautus

, where one character in the play,

Captivi

, jests that the father of another

is so avaricious that he uses cheap Samian ware in sacrifices to his own

genius, so as not to tempt the genius to steal it.In this passage, the genius is not identical to the person, as to

propitiate oneself would be absurd, and yet the genius also has the

avarice of the person; that is, the same character, the implication being, like

person, like genius.

Implied geniuses date to much earlier; for example, when

Horatius Cocles

defends the

Pons Sublicius

against an Etruscan crossing at

the beginning of the

Roman Republic

, after the bridge is cut down he

prays to the Tiber to bear him up as he swims across: Tiberine pater te,

sancte, precor …, “Holy father Tiber, I pray to you ….” The Tiber so

addressed is a genius. Although the word is not used here, in later

literature it is identified as one.

Horace

describes the genius as “the companion

which controls the natal star; the god of human nature, in that he is mortal for

each person, with a changing expression, white or black”.

Imperial genii

Genius of Domitian

Octavius Caesar

on return to Rome after the

final victory of the

Roman Civil War

at the

Battle of Actium

appeared to the Senate to be a

man of great power and success, clearly a mark of divinity. In recognition of

the prodigy they voted that all banquets should include a libation to his

genius. In concession to this sentiment he chose the name

Augustus

, capturing the numinous meaning of

English “august.” This line of thought was probably behind the later vote in 30

BC that he was divine, as the household cult of the Genius Augusti dates

from that time. It was propitiated at every meal along with the other household

numina.The vote began the tradition of the

divine emperors

; however, the divinity went

with the office and not the man. The Roman emperors gave ample evidence that

they personally were neither immortal nor divine.

Inscription on votive altar to the genius of

Legio VII Gemina

by L. Attius Macro

(CIL

II 5083)

If the genius

of the

imperator

, or commander of all troops, was

to be propitiated, so was that of all the units under his command. The

provincial troops expanded the idea of the genii of state; for example,

from Roman Britain have been found altars to the genii of Roma,

Roman aeterna, Britannia, and to every

legion

,

cohors

,

ala

and

centuria

in Britain, as well as to the

praetorium

of every

castra

and even to the

vexillae

.

Inscriptional dedications to genius were not confined to the military.

From

Gallia Cisalpina

under the empire are numerous

dedications to the genii of persons of authority and respect; in addition

to the emperor’s genius principis, were the geniuses of patrons of

freedmen, owners of slaves, patrons of guilds, philanthropists, officials,

villages, other divinities, relatives and friends. Sometimes the dedication is

combined with other words, such as “to the genius and honor” or in the case of

couples, “to the genius and Juno.”

Surviving from the time of the empire hundreds of dedicatory, votive and

sepulchral inscriptions ranging over the entire territory testify to a floruit

of genius worship as an official cult. Stock phrases were abbreviated:

GPR, genio populi Romani (“to the genius of the Roman people”); GHL,

genio huius loci (“to the genius of this place”); GDN, genio domini

nostri (“to the genius of our master”), and so on. In 392 AD with the final

victory of Christianity

Theodosius I

declared the worship of the Genii,

Lares

and

Penates

to be treason, ending their official

terms.

The concept, however, continued in representation and speech under different

names or with accepted modifications.

Roman iconography

Coins

The genius of a corporate social body is often a

cameo

theme on ancient coins: a

denarius

from Spain, 76–75 BC, featuring a bust

of the GPR (Genius Populi Romani, “Genius of the Roman People”) on

the

obverse

;

an aureus

of

Siscia

in

Croatia

, 270–275 AD, featuring a standing image

of the GENIUS ILLVR (Genius Exercitus Illyriciani,

“Genius of the Illyrian Army”) on the reverse;

an aureus

of Rome, 134–138 AD, with an image of a

youth holding a cornucopia and patera (sacrificial dish) and the inscription

GENIOPR, genio populi Romani, “to the genius of the Roman people,” on the

reverse.

|

Modern-era

representations

|

The sestertius, or sesterce, (pl. sestertii) was an

ancient Roman

coin. During the

Roman Republic

it was a small,

silver

coin issued only on rare occasions.

During the

Roman Empire

it was a large

brass

coin.

Helmed Roma head right, IIS behind

Dioscuri

riding right, ROMA in linear frame

below. RSC4, C44/7, BMC13.

The name sestertius (originally semis-tertius) means “2 ½”, the

coin’s original value in

asses

, and is a combination of semis

“half” and tertius “third”, that is, “the third half” (0 ½ being the

first half and 1 ½ the second half) or “half the third” (two units

plus half the third unit, or halfway between the second unit and

the third). Parallel constructions exist in

Danish

with halvanden (1 ½),

halvtredje (2 ½) and halvfjerde (3 ½). The form sesterce,

derived from

French

, was once used in preference to the

Latin form, but is now considered old-fashioned.

It is abbreviated as (originally IIS).

Example of a detailed portrait of

Hadrian

117 to 138

History

The sestertius was introduced c. 211 BC as a small

silver

coin valued at one-quarter of a

denarius

(and thus one hundredth of an

aureus

). A silver denarius was supposed to

weigh about 4.5 grams, valued at ten grams, with the silver sestertius valued at

two and one-half grams. In practice, the coins were usually underweight.

When the denarius was retariffed to sixteen asses (due to the gradual

reduction in the size of bronze denominations), the sestertius was accordingly

revalued to four asses, still equal to one quarter of a denarius. It was

produced sporadically, far less often than the denarius, through 44 BC.

under

Trajan Decius

250 AD

In or about 23 BC, with the coinage reform of

Augustus

, the denomination of sestertius was

introduced as the large brass denomination. Augustus tariffed the value of the

sestertius as 1/100 Aureus

. The sestertius was produced as the

largest brass

denomination until the late 3rd century

AD. Most were struck in the mint of

Rome but from AD 64 during the reign of

Nero (AD 54–68) and

Vespasian

(AD 69–79), the mint of

Lyon (Lugdunum), supplemented production. Lyon sestertii can

be recognised by a small globe, or legend stop), beneath the bust.[citation

needed]

The brass sestertius typically weighs in the region of 25 to 28 grammes, is

around 32–34 mm in diameter and about 4 mm thick. The distinction between

bronze

and brass was important to the Romans.

Their name for brass

was

orichalcum

, a word sometimes also spelled

aurichalcum (echoing the word for a gold coin, aureus), meaning

‘gold-copper’, because of its shiny, gold-like appearance when the coins were

newly struck (see, for example

Pliny the Elder

in his Natural History

Book 34.4).

Orichalcum

was considered, by weight, to be

worth about double that of bronze. This is why the half-sestertius, the

dupondius

, was around the same size and weight

as the bronze as, but was worth two asses.

Sestertii continued to be struck until the late 3rd century, although there

was a marked deterioration in the quality of the metal used and the striking

even though portraiture remained strong. Later emperors increasingly relied on

melting down older sestertii, a process which led to the zinc component being

gradually lost as it burned off in the high temperatures needed to melt copper (Zinc

melts at 419 °C, Copper

at 1085 °C). The shortfall was made up

with bronze and even lead. Later sestertii tend to be darker in appearance as a

result and are made from more crudely prepared blanks (see the

Hostilian

coin on this page).

The gradual impact of

inflation

caused by

debasement

of the silver currency meant that

the purchasing power of the sestertius and smaller denominations like the

dupondius and as was steadily reduced. In the 1st century AD, everyday small

change was dominated by the dupondius and as, but in the 2nd century, as

inflation bit, the sestertius became the dominant small change. In the 3rd

century silver coinage contained less and less silver, and more and more copper

or bronze. By the 260s and 270s the main unit was the double-denarius, the

antoninianus

, but by then these small coins

were almost all bronze. Although these coins were theoretically worth eight

sestertii, the average sestertius was worth far more in plain terms of the metal

they contained.

Some of the last sestertii were struck by

Aurelian

(270–275 AD). During the end of its

issue, when sestertii were reduced in size and quality, the

double sestertius

was issued first by

Trajan Decius

(249–251 AD) and later in large

quantity by the ruler of a breakaway regime in the West called

Postumus

(259–268 AD), who often used worn old

sestertii to

overstrike

his image and legends on. The double

sestertius was distinguished from the sestertius by the

radiate crown

worn by the emperor, a device

used to distinguish the dupondius from the as and the antoninianus from the

denarius.

Eventually, the inevitable happened. Many sestertii were withdrawn by the

state and by forgers, to melt down to make the debased antoninianus, which made

inflation worse. In the coinage reforms of the 4th century, the sestertius

played no part and passed into history.

Hadrian

, dupondius of

Antoninus Pius

, and as of

Marcus Aurelius

As a unit of account

The sestertius was also used as a standard unit of account, represented on

inscriptions with the monogram HS. Large values were recorded in terms of

sestertium milia, thousands of sestertii, with the milia often

omitted and implied. The hyper-wealthy general and politician of the late Roman

Republic,

Crassus

(who fought in the war to defeat

Spartacus

), was said by Pliny the Elder to have

had ‘estates worth 200 million sesterces’.

A loaf of bread cost roughly half a sestertius, and a

sextarius

(~0.5 liter) of

wine anywhere from less than half to more than 1 sestertius. One

modius

(6.67 kg) of

wheat

in 79 AD

Pompeii

cost 7 sestertii, of

rye

3 sestertii, a bucket 2 sestertii, a tunic 15 sestertii, a donkey 500 sestertii.

Records from Pompeii

show a

slave

being sold at auction for 6,252 sestertii.

A writing tablet from

Londinium

(Roman

London

), dated to c. 75–125 AD, records the

sale of a Gallic

slave girl called Fortunata for 600

denarii, equal to 2,400 sestertii, to a man called Vegetus. It is difficult to

make any comparisons with modern coinage or prices, but for most of the 1st

century AD the ordinary

legionary

was paid 900 sestertii per annum,

rising to 1,200 under

Domitian

(81-96 AD), the equivalent of 3.3

sestertii per day. Half of this was deducted for living costs, leaving the

soldier (if he was lucky enough actually to get paid) with about 1.65 sestertii

per day.

Perhaps a more useful comparison is a modern salary: in 2010 a private

soldier in the US Army (grade E-2) earned about $20,000 a year.

Numismatic value

A sestertius of

Nero

, struck at

Rome

in 64 AD. The reverse depicts

the emperor on horseback with a companion. The legend reads DECVRSIO,

‘a military exercise’. Diameter 35mm

Sestertii are highly valued by

numismatists

, since their large size gave

caelatores (engravers) a large area in which to produce detailed portraits

and reverse types. The most celebrated are those produced for

Nero (54-68 AD) between the years 64 and 68 AD, created by some of

the most accomplished coin engravers in history. The brutally realistic

portraits of this emperor, and the elegant reverse designs, greatly impressed

and influenced the artists of the

Renaissance

. The series issued by

Hadrian

(117-138 AD), recording his travels

around the Roman Empire, brilliantly depicts the Empire at its height, and

included the first representation on a coin of the figure of

Britannia

; it was revived by

Charles II

, and was a feature of

United Kingdom

coinage until the

2008 redesign

.

Very high quality examples can sell for over a million

dollars

at auction as of 2008, but the coins

were produced in such colossal abundance that millions survive.

|

|

|

Frequently Asked Questions How long until my order is shipped? shipment of your order after the receipt of payment. How will I know when the order was shipped? date should be used as a basis of estimating an arrival date. After you shipped the order, how long will the mail take? international shipping times cannot be estimated as they vary from country to country. I am not responsible for any USPS delivery delays, especially for an international package. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? and a Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity, issued by a world-renowned numismatic and antique expert that has identified over 10000 ancient coins and has provided them with the same guarantee. You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing. Compared to other certification companies, the certificate of authenticity is a $25-50 value. So buy a coin today and own a piece of history, guaranteed. Is there a money back guarantee? I offer a 30 day unconditional money back guarantee. I stand behind my coins and would be willing to exchange your order for either store credit towards other coins, or refund, minus shipping expenses, within 30 days from the receipt of your order. My goal is to have the returning customers for a lifetime, and I am so sure in my coins, their authenticity, numismatic value and beauty, I can offer such a guarantee. Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order?

You can contact me directly via ask seller a question and request my telephone number, or go to my About Me Page to get my contact information only in regards to items purchased on eBay. When should I leave feedback? order, please leave a positive. Please don’t leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. Also, if you sent an email, make sure to check for my reply in your messages before claiming that you didn’t receive a response. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. |