|

Constantine I ‘The Great’- Roman Emperor: 307-337 A.D. –

Bronze AE3 21mm (2.77 grams) London mint: 313-314 A.D.

Reference: RIC 10 (VII, London)

IMPCONSTANTINVSAVG – Laureate, cuirassed bust right.

SOLIINVICTOCOMITI Exe: S/F/PLN – Sol standing left, raising hand and holding

globe.

Royal/Imperial

symbols of power

Ruling dynasties often exploit pomp and ceremony with the use of

regalia

:

crowns

,

robes,

orb (globe) and sceptres

, some of which are reflections

of formerly practical objects. The use of language mechanisms also support this

differentiation with subjects talking of “the crown” and/or of “the

throne

” rather than referring directly to

personal names and items.

Monarchies

provide the most explicit

demonstration of tools to strengthen the elevation of leaders. Thrones sit high

on daises

leading to subjects lifting their gaze

(if they have permission) to contemplate the ruler. Architecture in general can

set leaders apart: note the symbolism inherent in the very name of the Chinese

imperial

Forbidden City

.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Roman Imperial

repoussé

silver

disc of Sol Invictus (3rd

century), found at

Pessinus

(British

Museum) Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) was the official

sun god

of the later

Roman Empire

and a patron of soldiers. In 274

the Roman emperor

Aurelian

made it an official

cult alongside the traditional Roman cults. Scholars disagree whether

the new deity was a refoundation of the ancient

Latin

cult of

Sol

,

a revival of the cult of

Elagabalus

or completely new.The god was

favored by emperors after Aurelian and appeared on their coins until

Constantine

.The last inscription referring to

Sol Invictus dates to 387 AD and there were enough devotees in the 5th century

that

Augustine

found it necessary to preach against

them.

It is commonly claimed that the date of 25 December for

Christmas

was selected in order to correspond

with the Roman festival of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, or “Birthday of

the Unconquered Sun”, but this view is challenged

Invictus as

epithet

Invictus

(“Unconquered, Invincible”) was an

epithet

for

several deities

of

classical Roman religion

, including the supreme

deity

Jupiter

, the war god

Mars

,

Hercules

,

Apollo

and

Silvanus

.[8]

Invictus was in use from the 3rd century BC, and was well-established as

a

cult

title when applied to

Mithras

from the 2nd century onwards. It has a

clear association[vague]

with solar deities and solar monism; as such, it became the preferred epithet of

Rome’s traditional

Sol

and the novel, short-lived Roman state cult

to

Elagabalus

, an

Emesan

solar deity who headed Rome’s official

pantheon under his

namesake emperor

.

The earliest dated use of Sol invictus is in a dedication from Rome,

AD 158. Another, stylistically dated to the 2nd century AD, is inscribed on a

Roman

phalera

: “inventori lucis soli invicto

augusto” (to the contriver of light, sol invictus augustus ). Here

“augustus” is most likely a further epithet of Sol as “august” (an elevated

being, divine or close to divinity), though the association of Sol with the

Imperial house would have been unmistakable and was already established in

iconography and stoic monism. These are the earliest attested examples of Sol as

invictus, but in AD 102 a certain

Anicetus

restored a shrine of Sol; Hijmans

(2009, 486, n. 22) is tempted “to link Anicetus’ predilection for Sol with his

name, the

Latinized

form of the Greek word ἀνίκητος,

which means invictus“.

Elagabalus

The first sun god consistently termed invictus was the

provincial Syrian

god

Elagabalus

. According to the

Historia Augusta

, the

teenaged Severan heir

adopted the name of his

deity and brought his cult image from Emesa to Rome. Once installed as emperor,

he neglected Rome’s traditional State deities and promoted his own as Rome’s

most powerful deity. This ended with his murder in 222.

The Historia Augusta refers to the deity Elagabalus as “also called

Jupiter and Sol” (fuit autem Heliogabali vel Iovis vel Solis).This has

been seen as an abortive attempt to impose the Syrian sun god on Rome;

but because it is now clear that the Roman cult of Sol remained

firmly established in Rome throughout the Roman period,this Syrian

Sol Elagabalus

has become no more relevant to

our understanding of the Roman

Sol

than, for example, the Syrian

Jupiter Dolichenus

is for our understanding of

the Roman Jupiter.

Aurelian

The Roman gens

Aurelian was associated with the cult

of Sol. After his victories in the East, the Emperor

Aurelian

thoroughly reformed the Roman cult of

Sol, elevating the sun-god to one of the premier divinities of the Empire. Where

previously priests of Sol had been simply

sacerdotes

and tended to belong to lower

ranks of Roman society, they were now pontifices and members of the new

college of pontifices

instituted by Aurelian.

Every pontifex of Sol was a member of the senatorial elite, indicating that the

priesthood of Sol was now highly prestigious. Almost all these senators held

other priesthoods as well, however, and some of these other priesthoods take

precedence in the inscriptions in which they are listed, suggesting that they

were considered more prestigious than the priesthood of Sol.Aurelian also built

a new temple for Sol, bringing the total number of temples for the god in Rome

to (at least) four[21]

He also instituted games in honor of the sun god, held every four years from AD

274 onwards.

The identity of Aurelian’s Sol Invictus has long been a subject of scholarly

debate. Based on the

Historia Augusta

, some scholars have argued

that it was based on

Sol Elagablus

(or Elagabla) of

Emesa

. Others, basing their argument on

Zosimus

, suggest that it was based on the

Helios

, the solar god of

Palmyra

on the grounds that Aurelian placed and

consecrated a cult statue of Helios looted from Palmyra in the temple of Sol

Invictus. Professor Gary Forsythe discusses these arguments and add a third more

recent one based on the work of Steven Hijmans. Hijmans argues that Aurelian’s

solar deity was simply the traditional Greco-Roman Sol Invictus.

Constantine

Emperors portrayed Sol Invictus on their official coinage, with a wide range

of legends, only a few of which incorporated the epithet invictus, such

as the legend SOLI INVICTO COMITI, claiming the Unconquered Sun

as a companion to the Emperor, used with particular frequency by Constantine.

Statuettes of Sol Invictus, carried by the standard-bearers,

appear in three places in reliefs on the

Arch of Constantine

. Constantine’s official

coinage continues to bear images of Sol until 325/6. A

solidus

of Constantine as well as a gold

medallion from his reign depict the Emperor’s bust in profile twinned (“jugate”)

with Sol Invictus, with the legend INVICTUS CONSTANTINUS

Constantine decreed (March 7, 321) dies Solis—day of the sun, “Sunday“—as

the Roman day of rest [CJ3.12.2]:

- On the venerable day of the Sun let the magistrates and people residing

in cities rest, and let all workshops be closed. In the country however

persons engaged in agriculture may freely and lawfully continue their

pursuits because it often happens that another day is not suitable for

grain-sowing or vine planting; lest by neglecting the proper moment for such

operations the bounty of heaven should be lost.

Constantine’s triumphal arch was carefully positioned to align with the

colossal statue of Sol

by the

Colosseum

, so that Sol formed the dominant

backdrop when seen from the direction of the main approach towards the arch.[26]

Sol and the

other Roman Emperors

Berrens

deals with coin-evidence of Imperial connection to the Solar

cult. Sol is depicted sporadically on imperial coins in the 1st and 2nd

centuries AD, then more frequently from

Septimius Severus

onwards until AD 325/6.

Sol invictus appears on coin legends from AD 261, well before the reign of

Aurelian.

Connections between the imperial radiate crown and the cult of

Sol are postulated.

Augustus

was posthumously depicted with radiate

crown, as were living emperors from

Nero (after AD 65) to

Constantine

. Some modern scholarship interprets

the imperial radiate crown as a divine, solar association rather than an overt

symbol of Sol; Bergmann calls it a pseudo-object designed to disguise the divine

and solar connotations that would otherwise be politically controversial

but there is broad agreement that coin-images showing the

imperial radiate crown are stylistically distinct from those of the solar crown

of rays; the imperial radiate crown is depicted as a real object rather than as

symbolic light. Hijmans argues that the Imperial radiate crown represents the

honorary wreath awarded to

Augustus

, perhaps posthumously, to commemorate

his victory at the

battle of Actium

; he points out that

henceforth, living emperors were depicted with radiate crowns, but state divi

were not. To Hijmans this implies the radiate crown of living emperors as a link

to Augustus. His successors automatically inherited (or sometimes acquired) the

same offices and honours due to Octavian as “saviour of the Republic” through

his victory at Actium, piously attributed to Apollo-Helios. Wreaths awarded to

victors at the Actian Games were radiate.

Sol

Invictus and Christianity and Judaism

Mosaic of Christ as

Sol

or

Apollo-Helios

in Mausoleum M in the

pre-4th-century necropolis beneath[33]

St. Peter’s in the Vatican

, which

many interpret as representing Christ

The

Philocalian calendar

of AD 354 gives a festival

of “Natalis Invicti” on 25 December. There is limited evidence that this

festival was celebrated before the mid-4th century.

The idea that Christians chose to celebrate the birth of Jesus on 25 December

because this was the date of an already existing festival of the Sol Invictus

was expressed in an annotation to a manuscript of a work by 12th-century Syrian

bishop

Jacob Bar-Salibi

. The scribe who added it

wrote: “It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the

birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In

these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when

the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this

festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be

solemnised on that day.”

This idea became popular especially in the 18th and 19th centuries

and is still widely accepted.

In the judgement of the Church of England Liturgical Commission, this view

has been seriously challenged

by a view based on an old tradition, according to which the

date of Christmas was fixed at nine months after 25 March, the date of the

vernal equinox, on which the

Annunciation

was celebrated.

The Jewish calendar date of 14 Nisan was believed to be that

of the beginning of creation, as well as of the Exodus and so of Passover, and

Christians held that the new creation, both the death of Jesus and the beginning

of his human life, occurred on the same date, which some put at 25 March in the

Julian calendar.[40][42][43]

It was a traditional Jewish belief that great men lived a whole number of years,

without fractions, so that Jesus was considered to have been conceived on 25

March, as he died on 25 March, which was calculated to have coincided with 14

Nisan.[44]

Sextus Julius Africanus

(c.160 – c.240) gave 25

March as the day of creation and of the conception of Jesus.

The tractate De solstitia et aequinoctia conceptionis et

nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae falsely

attributed to

John Chrysostom

also argued that Jesus was

conceived and crucified on the same day of the year and calculated this as 25

March.

A passage of the Commentary on the prophet Daniel by

Hippolytus of Rome

, written in about 204, has

also been appealed to.

Among those who have put forward this view are Louis Duchesne,Thomas J.

Talley, David J. Rothenberg, J. Neil Alexander, and Hugh Wybrew.

Not all scholars who view the celebration of the birth of Jesus on 25

December as motivated by the choice of the winter solstice rather than

calculated on the basis of the belief that he was conceived and died on 25 March

agree that it constituted a deliberate Christianization of a festival of the

Birthday of the Unconquered Sun. Michael Alan Anderson writes:

Both the sun and Christ were said to be born anew on December 25. But

while the solar associations with the birth of Christ created powerful

metaphors, the surviving evidence does not support such a direct association

with the Roman solar festivals. The earliest documentary evidence for the

feast of Christmas makes no mention of the coincidence with the winter

solstice. Thomas Talley has shown that, although the Emperor Aurelian’s

dedication of a temple to the sun god in the Campus Martius (C.E. 274)

probably took place on the ‘Birthday of the Invincible Sun’ on December 25,

the cult of the sun in pagan Rome ironically did not celebrate the winter

solstice nor any of the other quarter-tense days, as one might expect. The

origins of Christmas, then, may not be expressly rooted in the Roman

festival.

The same point is made by Hijmans: “It is cosmic symbolism…which inspired

the Church leadership in Rome to elect the southern solstice, December 25, as

the birthday of Christ … While they were aware that pagans called this day the

‘birthday’ of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any

role in their choice of date for Christmas.” He also states that, “while the

winter solstice on or around December 25 was well established in the Roman

imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on

that day antedated the celebration of Christmas”.

The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought also remarks on the

uncertainty about the order of precedence between the celebrations of the

Birthday of the Unconquered Sun and the birthday of Jesus: “This ‘calculations’

hypothesis potentially establishes 25 December as a Christian festival before

Aurelian’s decree, which, when promulgated, might have provided for the

Christian feast both opportunity and challenge.”

Susan K. Roll also calls “most extreme” the unproven hypothesis that “would

call Christmas point-blank a ‘christianization’ of Natalis Solis Invicti, a

direct conscious appropriation of the pre-Christian feast, arbitrarily placed on

the same calendar date, assimilating and adapting some of its cosmic symbolism

and abruptly usurping any lingering habitual loyalty that newly-converted

Christians might feel to the feasts of the state gods”.

The comparison of Christ with the astronomical

Sun

is common in ancient Christian writings.

In the 5th century,

Pope Leo I

(the Great) spoke in several sermons

on the Feast of the Nativity of how the celebration of Christ’s birth coincided

with increase of the sun’s position in the sky. An example is: “But this

Nativity which is to be adored in heaven and on earth is suggested to us by no

day more than this when, with the early light still shedding its rays on nature,

there is borne in upon our senses the brightness of this wondrous mystery.

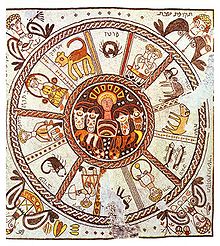

Mosaic in the

Beth Alpha

synagogue, with the sun

in the centre, surrounded by the twelve zodiac constellations and

with the four seasons associated inaccurately with the

constellations

A study of

Augustine of Hippo

remarks that his exhortation

in a Christmas sermon, “Let us celebrate this day as a feast not for the sake of

this sun, which is beheld by believers as much as by ourselves, but for the sake

of him who created the sun”, shows that he was aware of the coincidence of the

celebration of Christmas and the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun, although this

pagan festival was celebrated at only a few places and was originally a

peculiarity of the Roman city calendar. It adds: “He also believes, however,

that there is a reliable tradition which gives 25 December as the actual date of

the birth of our Lord.”

By “the sun of righteousness” in

Malachi 4:2

“the

fathers

, from

Justin

downward, and nearly all the earlier

commentators understand Christ, who is supposed to be described as the

rising sun”.

The

New Testament

itself contains a hymn fragment:

“Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you.”

Clement of Alexandria

wrote of “the Sun of the

Resurrection, he who was born before the dawn, whose beams give light”.

Christians adopted the image of the Sun (Helios

or Sol Invictus) to represent Christ. In this portrayal he is a beardless figure

with a flowing cloak in a chariot drawn by four white horses, as in the mosaic

in Mausoleum M discovered under

Saint Peter’s Basilica

and in an

early-4th-century catacomb fresco.

Clement of Alexandria had spoken of Christ driving his chariot

in this way across the sky. The nimbus of the figure under Saint Peter’s

Basilica is described by some as rayed,

as in traditional pre-Christian representations, but another

has said: “Only the cross-shaped nimbus makes the Christian significance

apparent” (emphasis added). Yet another has interpreted the figure as a

representation of the sun with no explicit religious reference whatever, pagan

or Christian.

The traditional image of the sun is used also in Jewish art. A mosaic floor

in Hamat Tiberias

presents

David

as Helios surrounded by a ring with the

signs of the zodiac

.As well as in Hamat Tiberias, figures of

Helios or Sol Invictus also appear in several of the very few surviving schemes

of decoration surviving from Late Antique

synagogues

, including

Beth Alpha

,

Husefah

(Husefa) and

Naaran

, all now in

Israel

. He is shown in floor mosaics, with the

usual radiate halo, and sometimes in a

quadriga

, in the central roundel of a circular

representation of the zodiac or the seasons. These combinations “may have

represented to an agricultural Jewish community the perpetuation of the annual

cycle of the universe or … the central part of a calendar”.

Constantine the Great (Latin:

Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus Augustus;

27 February c. 272 – 22 May 337), also known as Constantine I or Saint

Constantine, was

Roman Emperor

from 306 to 337. Well known for

being the first Roman emperor to

be converted

to

Christianity

, Constantine and co-Emperor

Licinius

issued the

Edict of Milan

in 313, which proclaimed

tolerance of all religions

throughout the

empire.

Constantine defeated the emperors

Maxentius

and

Licinius

during civil wars. He also fought

successfully against the

Franks

,

Alamanni

,

Visigoths

, and

Sarmatians

during his reign — even resettling

parts of Dacia

which had been abandoned during the

previous century. Constantine built a new imperial residence at

Byzantium

, naming it

New Rome

. However, in Constantine’s honor,

people called it

Constantinople

, which would later be the

capital of what is now known as the

Byzantine Empire

for over one thousand years.

Because of this, he is thought of as the founder of the Byzantine Empire.

Flavius Valerius Constantinus, as he was originally named, was born in the

city of Naissus,

Dardania

province of

Moesia

, in present-day

Niš,

Serbia

, on 27 February of an uncertain year,

probably near 272.

His father was

Flavius Constantius

, a native of

Dardania

province of Moesia (later

Dacia Ripensis

). Constantius was a tolerant and

politically skilled man. Constantine probably spent little time with his father.

Constantius was an officer in the Roman army, part of the Emperor

Aurelian

‘s imperial bodyguard. Constantius

advanced through the ranks, earning the

governorship

of

Dalmatia

from Emperor

Diocletian

, another of Aurelian’s companions

from

Illyricum

, in 284 or 285.Constantine’s mother

was

Helena

, a

Bithynian

woman of low social standing.It is

uncertain whether she was legally married to Constantius or merely his concubine

Helena gave birth to the future emperor

Constantine I

on 27 February of an uncertain

year soon after 270 (probably around 272). At the time, she was in

Naissus

(Niš,

Serbia

). In order to obtain a wife more

consonant with his rising status, Constantius divorced Helena some time before

289, when he married

Theodora

, Maximian’s daughter.(The narrative

sources date the marriage to 293, but the

Latin panegyric

of 289 refers to the couple as

already married). Helena and her son were dispatched to the court of

Diocletian

at Nicomedia, where Constantine grew

to be a member of the inner circle. Helena never remarried and lived for a time

in obscurity, though close to her only son, who had a deep regard and affection

for her.

She received the title of

Augusta

in 325 and died in 330 with her son

at her side. She was buried in the

Mausoleum of Helena

, outside

Rome on the

Via Labicana

. Her

sarcophagus

is on display in the

Pio-Clementine Vatican Museum

, although the

connection is often questioned, next to her is the sarcophagus of her

granddaughter Saint Constantina (Saint Constance). The elaborate reliefs contain

hunting scenes. During her life, she gave many presents to the poor, released

prisoners and mingled with the ordinary worshippers in modest attire.

Constantine received a formal education at Diocletian’s court, where he

learned Latin literature, Greek, and philosophy.

On 1 May 305, Diocletian, as a result of a debilitating sickness taken in the

winter of 304–5, announced his resignation. In a parallel ceremony in Milan,

Maximian did the same. Lactantius states that Galerius manipulated the weakened

Diocletian into resigning, and forced him to accept Galerius’ allies in the

imperial succession. According to Lactantius, the crowd listening to

Diocletian’s resignation speech believed, until the very last moment, that

Diocletian would choose Constantine and

Maxentius

(Maximian’s son) as his successors.

It was not to be: Constantius and Galerius were promoted to Augusti, while

Severus

and

Maximin

were appointed their Caesars

respectively. Constantine and Maxentius were ignored.

Constantine recognized the implicit danger in remaining at Galerius’ court,

where he was held as a virtual hostage. His career depended on being rescued by

his father in the west. Constantius was quick to intervene. In the late spring

or early summer of 305, Constantius requested leave for his son, to help him

campaign in Britain. After a long evening of drinking, Galerius granted the

request. Constantine’s later propaganda describes how he fled the court in the

night, before Galerius could change his mind. He rode from

post-house

to post-house at high speed,

hamstringing

every horse in his wake.By the

time Galerius awoke the following morning, Constantine had fled too far to be

caught. Constantine joined his father in

Gaul

, at Bononia (Boulogne)

before the summer of 305.

From Bononia they crossed the

Channel

to Britain and made their way to

Eboracum

(York),

capital of the province of

Britannia Secunda

and home to a large military

base. Constantine was able to spend a year in northern Britain at his father’s

side, campaigning against the

Picts

beyond

Hadrian’s Wall

in the summer and autumn.

Constantius’s campaign, like that of

Septimius Severus

before it, probably advanced

far into the north without achieving great success. Constantius had become

severely sick over the course of his reign, and died on 25 July 306 in

Eboracum

(York).

Before dying, he declared his support for raising Constantine to the rank of

full Augustus. The

Alamannic

king

Chrocus

, a barbarian taken into service under

Constantius, then proclaimed Constantine as Augustus. The troops loyal to

Constantius’ memory followed him in acclamation. Gaul and Britain quickly

accepted his rule; Iberia, which had been in his father’s domain for less than a

year, rejected it.

Constantine sent Galerius an official notice of Constantius’s death and his

own acclamation. Along with the notice, he included a portrait of himself in the

robes of an Augustus. The portrait was wreathed in

bay

. He requested recognition as heir to his

father’s throne, and passed off responsibility for his unlawful ascension on his

army, claiming they had “forced it upon him”.Galerius was put into a fury by the

message; he almost set the portrait on fire. His advisers calmed him, and argued

that outright denial of Constantine’s claims would mean certain war.Galerius was

compelled to compromise: he granted Constantine the title “Caesar” rather than

“Augustus” (the latter office went to Severus instead). Wishing to make it clear

that he alone gave Constantine legitimacy, Galerius personally sent Constantine

the emperor’s traditional

purple robes

. Constantine accepted the

decision. Constantine’s share of the Empire consisted of Britain, Gaul, and

Spain.

Because Constantine was still largely untried and had a hint of illegitimacy

about him, he relied on his father’s reputation in his early propaganda: the

earliest panegyrics to Constantine give as much coverage to his father’s deeds

as to those of Constantine himself.

Constantine’s military skill and building projects soon gave

the panegyrist the opportunity to comment favorably on the similarities between

father and son, and Eusebius remarked that Constantine was a “renewal, as it

were, in his own person, of his father’s life and reign”. Constantinian coinage,

sculpture and oratory also shows a new tendency for disdain towards the

“barbarians” beyond the frontiers. After Constantine’s victory over the

Alemanni, he minted a coin issue depicting weeping and begging Alemannic

tribesmen—”The Alemanni conquered”—beneath the phrase “Romans’ rejoicing”.There

was little sympathy for these enemies. As his panegyrist declared: “It is a

stupid clemency that spares the conquered foe.”

In 310, a dispossessed and power-hungry Maximian rebelled against Constantine

while Constantine was away campaigning against the Franks. Maximian had been

sent south to Arles with a contingent of Constantine’s army, in preparation for

any attacks by Maxentius in southern Gaul. He announced that Constantine was

dead, and took up the imperial purple. In spite of a large donative pledge to

any who would support him as emperor, most of Constantine’s army remained loyal

to their emperor, and Maximian was soon compelled to leave. Constantine soon

heard of the rebellion, abandoned his campaign against the Franks, and marched

his army up the Rhine. At Cabillunum (Chalon-sur-Saône),

he moved his troops onto waiting boats to row down the slow waters of the

Saône

to the quicker waters of the

Rhone

. He disembarked at

Lugdunum

(Lyon).Maximian

fled to Massilia (Marseille),

a town better able to withstand a long siege than Arles. It made little

difference, however, as loyal citizens opened the rear gates to Constantine.

Maximian was captured and reproved for his crimes. Constantine granted some

clemency, but strongly encouraged his suicide. In July 310, Maximian hanged

himself.

The death of Maximian required a shift in Constantine’s public image. He

could no longer rely on his connection to the elder emperor Maximian, and needed

a new source of legitimacy.In a speech delivered in Gaul on 25 July 310, the

anonymous orator reveals a previously unknown dynastic connection to

Claudius II

, a third-century emperor famed for

defeating the Goths and restoring order to the empire. Breaking away from

tetrarchic models, the speech emphasizes Constantine’s ancestral prerogative to

rule, rather than principles of imperial equality. The new ideology expressed in

the speech made Galerius and Maximian irrelevant to Constantine’s right to rule.

Indeed, the orator emphasizes ancestry to the exclusion of all other factors:

“No chance agreement of men, nor some unexpected consequence of favor, made you

emperor,” the orator declares to Constantine.

A gold multiple of “Unconquered Constantine” with

Sol Invictus

, struck in 313. The use of

Sol’s image appealed to both the educated citizens of Gaul, who would

recognize

in it Apollo’s patronage of

Augustus

and the arts; and to Christians,

who found solar monotheism less objectionable than the traditional pagan

pantheon.

The oration also moves away from the religious ideology of the Tetrarchy,

with its focus on twin dynasties of

Jupiter

and

Hercules

. Instead, the orator proclaims that

Constantine experienced a divine vision of

Apollo

and

Victory

granting him

laurel wreaths

of health and a long reign. In

the likeness of Apollo Constantine recognized himself as the saving figure to

whom would be granted “rule of the whole world”, as the poet Virgil had once

foretold. The oration’s religious shift is paralleled by a similar shift in

Constantine’s coinage. In his early reign, the coinage of Constantine advertised

Mars

as his patron. From 310 on, Mars was

replaced by

Sol Invictus

, a god conventionally identified

with Apollo.

By the middle of 310, Galerius had become too ill to involve himself in

imperial politics. His final act survives: a letter to the provincials posted in

Nicomedia on 30 April 311, proclaiming an end to the persecutions, and the

resumption of religious toleration. He died soon after the edict’s proclamation,

destroying what little remained of the tetrarchy. Maximin mobilized against

Licinius, and seized Asia Minor. A hasty peace was signed on a boat in the

middle of the Bosphorus. While Constantine toured Britain and Gaul, Maxentius

prepared for war.He fortified northern Italy, and strengthened his support in

the Christian community by allowing it to elect a new

Bishop

of

Rome

,

Eusebius

.

Constantine’s advisers and generals cautioned against preemptive attack on

Maxentius; even his soothsayers recommended against it, stating that the

sacrifices had produced unfavorable omens. Constantine, with a spirit that left

a deep impression on his followers, inspiring some to believe that he had some

form of supernatural guidance, ignored all these cautions. Early in the spring

of 312,Constantine crossed the

Cottian Alps

with a quarter of his army, a

force numbering about 40,000.The first town his army encountered was Segusium (Susa,

Italy

), a heavily fortified town that shut its

gates to him. Constantine ordered his men to set fire to its gates and scale its

walls. He took the town quickly. Constantine ordered his troops not to loot the

town, and advanced with them into northern Italy.

At the approach to the west of the important city of Augusta Taurinorum (Turin,

Italy), Constantine met a large force of heavily armed Maxentian cavalry. In the

ensuing

battle

Constantine’s army encircled Maxentius’

cavalry, flanked them with his own cavalry, and dismounted them with blows from

his soldiers’ iron-tipped clubs. Constantine’s armies emerged victorious. Turin

refused to give refuge to Maxentius’ retreating forces, opening its gates to

Constantine instead.

Other cities of the north Italian plain sent Constantine

embassies of congratulation for his victory. He moved on to Milan, where he was

met with open gates and jubilant rejoicing. Constantine rested his army in Milan

until mid-summer 312, when he moved on to

Brixia

(Brescia).

Brescia’s army was easily dispersed, and Constantine quickly advanced to

Verona

, where a large Maxentian force was

camped. Ruricius Pompeianus, general of the Veronese forces and Maxentius’

praetorian prefect, was in a strong defensive position, since the town was

surrounded on three sides by the

Adige

. Constantine sent a small force north of

the town in an attempt to cross the river unnoticed. Ruricius sent a large

detachment to counter Constantine’s expeditionary force, but was defeated.

Constantine’s forces successfully surrounded the town and laid siege. Ruricius

gave Constantine the slip and returned with a larger force to oppose

Constantine. Constantine refused to let up on the siege, and sent only a small

force to oppose him. In the desperately fought

encounter

that followed, Ruricius was killed

and his army destroyed.Verona surrendered soon afterwards, followed by

Aquileia

, Mutina (Modena),

and

Ravenna

. The road to Rome was now wide open to

Constantine.

Maxentius prepared for the same type of war he had waged against Severus and

Galerius: he sat in Rome and prepared for a siege. He still controlled Rome’s

praetorian guards, was well-stocked with African grain, and was surrounded on

all sides by the seemingly impregnable

Aurelian Walls

. He ordered all bridges across

the Tiber

cut, reportedly on the counsel of the

gods, and left the rest of central Italy undefended; Constantine secured that

region’s support without challenge. Constantine progressed slowly along the

Via Flaminia

, allowing the weakness of

Maxentius to draw his regime further into turmoil. Maxentius’ support continued

to weaken: at chariot races on 27 October, the crowd openly taunted Maxentius,

shouting that Constantine was invincible. Maxentius, no longer certain that he

would emerge from a siege victorious, built a temporary boat bridge across the

Tiber in preparation for a field battle against Constantine. On 28 October 312,

the sixth anniversary of his reign, he approached the keepers of the

Sibylline Books

for guidance. The keepers

prophesied that, on that very day, “the enemy of the Romans” would die.

Maxentius advanced north to meet Constantine in battle.

Maxentius organized his forces—still twice the size of Constantine’s—in long

lines facing the battle plain, with their backs to the river. Constantine’s army

arrived at the field bearing unfamiliar symbols on either its standards or its

soldiers’ shields. Constantine was visited by a dream the night before the

battle, wherein he was advised “to mark the heavenly sign of God on the shields

of his soldiers…by means of a slanted letter X with the top of its head bent

round, he marked Christ on their shields.” Eusebius describes the sign as

Chi

(Χ) traversed by

Rho

(Ρ): ☧, a symbol representing the first two

letters of the Greek spelling of the word Christos or Christ.

Constantine deployed his own forces along the whole length of Maxentius’

line. He ordered his cavalry to charge, and they broke Maxentius’ cavalry. He

then sent his infantry against Maxentius’ infantry, pushing many into the Tiber

where they were slaughtered and drowned. The battle was brief: Maxentius’ troops

were broken before the first charge. Maxentius’ horse guards and praetorians

initially held their position, but broke under the force of a Constantinian

cavalry charge; they also broke ranks and fled to the river. Maxentius rode with

them, and attempted to cross the bridge of boats, but he was pushed by the mass

of his fleeing soldiers into the Tiber, and drowned.

In Rome

Constantine entered Rome on 29 October.He staged a grand

adventus

in the city, and was met with

popular jubilation. Maxentius’ body was fished out of the Tiber and decapitated.

His head was paraded through the streets for all to see. Unlike his

predecessors, Constantine neglected to make the trip to the

Capitoline Hill

and perform customary

sacrifices at the

Temple of Jupiter

. He did, however, choose to

honor the

Senatorial

Curia

with a visit, where he promised to

restore its ancestral privileges and give it a secure role in his reformed

government: there would be no revenge against Maxentius’ supporters.In response,

the Senate decreed him “title of the first name”, which meant his name would be

listed first in all official documents, and acclaimed him as “the greatest

Augustus”. He issued decrees returning property lost under Maxentius, recalling

political exiles, and releasing Maxentius’ imprisoned opponents.

In the following years, Constantine gradually consolidated his military

superiority over his rivals in the crumbling Tetrarchy. In 313, he met

Licinius

in

Milan

to secure their alliance by the marriage

of Licinius and Constantine’s half-sister

Constantia

. During this meeting, the emperors

agreed on the so-called

Edict of Milan

,officially granting full

tolerance to Christianity and all religions in the Empire.The document had

special benefits for Christians, legalizing their religion and granting them

restoration for all property seized during Diocletian’s persecution.

In the year 320,

Licinius

reneged on the religious freedom

promised by the

Edict of Milan

in 313 and began to oppress

Christians anew, generally without bloodshed, but resorting to confiscations and

sacking of Christian office-holders.That became a challenge to Constantine in

the West, climaxing in the great civil war of 324. Licinius, aided by

Goth

mercenaries

, represented the past and the

ancient Pagan

faiths. Constantine and his

Franks

marched under the standard of the

labarum

, and both sides saw the battle in

religious terms. Outnumbered, but fired by their zeal, Constantine’s army

emerged victorious in the

Battle of Adrianople

. Licinius fled across the

Bosphorus and appointed

Martius Martinianus

, the commander of his

bodyguard, as Caesar, but Constantine next won the

Battle of the Hellespont

, and finally the

Battle of Chrysopolis

on 18 September

324.Licinius and Martinianus surrendered to Constantine at Nicomedia on the

promise their lives would be spared: they were sent to live as private citizens

in Thessalonica and Cappadocia respectively, but in 325 Constantine accused

Licinius of plotting against him and had them both arrested and hanged;

Licinius’s son (the son of Constantine’s half-sister) was also killed. Thus

Constantine became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

Foundation of

Constantinople

Licinius’ defeat came to represent the defeat of a rival center of Pagan and

Greek-speaking political activity in the East, as opposed to the Christian and

Latin-speaking Rome, and it was proposed that a new Eastern capital should

represent the integration of the East into the Roman Empire as a whole, as a

center of learning, prosperity, and cultural preservation for the whole of the

Eastern Roman Empire

. Among the various

locations proposed for this alternative capital, Constantine appears to have

toyed earlier with

Serdica

(present-day

Sofia

), as he was reported saying that “Serdica

is my Rome“. Sirmium

and

Thessalonica

were also considered. Eventually,

however, Constantine decided to work on the Greek city of

Byzantium

, which offered the advantage of

having already been extensively rebuilt on Roman patterns of urbanism, during

the preceding century, by

Septimius Severus

and

Caracalla

, who had already acknowledged its

strategic importance. The city was then renamed Constantinopolis

(“Constantine’s City” or

Constantinople

in English), and issued special

commemorative coins in 330 to honor the event. The new city was protected by the

relics of the

True Cross

, the

Rod of Moses

and other holy

relics

, though a cameo now at the

Hermitage Museum

also represented Constantine

crowned by the tyche

of the new city. The figures of old gods

were either replaced or assimilated into a framework of

Christian symbolism

. Constantine built the new

Church of the Holy Apostles

on the site of a

temple to Aphrodite

. Generations later there was the

story that a

divine vision

led Constantine to this spot, and

an angel

no one else could see, led him on a

circuit of the new walls. The capital would often be compared to the ‘old’ Rome

as Nova Roma Constantinopolitana, the “New Rome of Constantinople”.

Constantine the Great, mosaic in

Hagia Sophia

, c. 1000

Religious policy

Constantine is perhaps best known for being the first “Christian” Roman

emperor. Scholars debate whether Constantine adopted his mother

St. Helena

‘s

Christianity in his youth, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of

his life.

Constantine was over 40 when he finally declared himself a Christian, writing to

Christians to make clear that he believed he owed his successes to the

protection of the Christian High God alone.Throughout his rule, Constantine

supported the Church financially, built basilicas, granted privileges to clergy

(e.g. exemption from certain taxes), promoted Christians to high office, and

returned property confiscated during the Diocletianic persecution.His most

famous building projects include the

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

, and

Old Saint Peter’s Basilica

.

However, Constantine certainly did not patronize Christianity alone. After

gaining victory in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312), a triumphal arch—the

Arch of Constantine

—was built (315) to

celebrate his triumph. The arch is most notably decorated with images of the

goddess

Victoria

and, at the time of its dedication,

sacrifices to gods like

Apollo

,

Diana

, and

Hercules

were made. Most notably absent from

the Arch are any depictions whatsoever regarding Christian symbolism.

Later in 321, Constantine instructed that Christians and non-Christians

should be united in observing the venerable day of the sun, referencing

the sun-worship

that

Aurelian

had established as an official cult.

Furthermore, and long after his oft alleged “conversion” to Christianity,

Constantine’s coinage continued to carry the symbols of the sun. Even after the

pagan gods had disappeared from the coinage, Christian symbols appeared only as

Constantine’s personal attributes: the

chi rho

between his hands or on his

labarum

, but never on the coin itself. Even

when Constantine dedicated the new capital of Constantinople, which became the

seat of Byzantine Christianity for a millennium, he did so wearing the

Apollonian

sun-rayed

Diadem

; no Christian symbols were present at

this dedication.

Constantine made new laws regarding the

Jews. They were forbidden to own Christian slaves or to

circumcise

their slaves.

Administrative reforms

Beginning in the mid-3rd century the emperors began to favor members of the

equestrian order

over senators, who had had a

monopoly on the most important offices of state. Senators were stripped of the

command of legions and most provincial governorships (as it was felt that they

lacked the specialized military upbringing needed in an age of acute defense

needs), such posts being given to equestrians by Diocletian and his

colleagues—following a practice enforced piecemeal by their predecessors. The

emperors however, still needed the talents and the help of the very rich, who

were relied on to maintain social order and cohesion by means of a web of

powerful influence and contacts at all levels. Exclusion of the old senatorial

aristocracy threatened this arrangement.

In 326, Constantine reversed this pro-equestrian trend, raising many

administrative positions to senatorial rank and thus opening these offices to

the old aristocracy, and at the same time elevating the rank of already existing

equestrians office-holders to senator, eventually wiping out the equestrian

order—at least as a bureaucratic rank—in the process. One could become a

senator, either by being elected

praetor

or (in most cases) by fulfilling a

function of senatorial rank: from then on, holding of actual power and social

status were melded together into a joint imperial hierarchy. At the same time,

Constantine gained with this the support of the old nobility, as the Senate was

allowed itself to elect praetors and

quaestors

, in place of the usual practice of

the emperors directly creating new magistrates (adlectio).

The Senate as a body remained devoid of any significant power; nevertheless,

the senators, who had been marginalized as potential holders of imperial

functions during the 3rd century, could now dispute such positions alongside

more upstart bureaucrats. Some modern historians see in those administrative

reforms an attempt by Constantine at reintegrating the senatorial order into the

imperial administrative elite to counter the possibility of alienating pagan

senators from a Christianized imperial rule.

Constantine’s reforms had to do only with the civilian administration: the

military chiefs, who since the

Crisis of the Third Century

had risen from the

ranks, remained outside the senate, in which they were included only by

Constantine’s children.

Monetary reforms

After the

runaway inflation of the third century

,

associated with the production of

fiat money

to pay for public expenses,

Diocletian had tried unsuccessfully to reestablish trustworthy minting of silver

and

billon

coins. The failure of the various

Diocletianic attempts at the restoration of a functioning silver coin resided in

the fact that the silver currency was overvalued in terms of its actual metal

content, and therefore could only circulate at much discounted rates. Minting of

the Diocletianic “pure” silver

argenteus

ceased, therefore, soon after

305, while the billon currency continued to be used until the 360s. From the

early 300s on, Constantine forsook any attempts at restoring the silver

currency, preferring instead to concentrate on minting large quantities of good

standard gold pieces—the

solidus

, 72 of which made a pound of gold. New

(and highly debased) silver pieces would continue to be issued during

Constantine’s later reign and after his death, in a continuous process of

retariffing, until this billon minting eventually ceased, de jure, in

367, with the silver piece being de facto continued by various

denominations of bronze coins, the most important being the

centenionalis

. Later emperors like

Julian the Apostate

tried to present themselves

as advocates of the humiles by insisting on trustworthy mintings of the

bronze currency.

Constantine’s monetary policy were closely associated with his religious

ones, in that increased minting was associated with measures of

confiscation—taken since 331 and closed in 336—of all gold, silver and bronze

statues from pagan temples, who were declared as imperial property and, as such,

as monetary assets. Two imperial commissioners for each province had the task of

getting hold of the statues and having them melded for immediate minting—with

the exception of a number of bronze statues who were used as public monuments

for the beautification of the new capital in Constantinople.

Later campaigns

Constantine considered Constantinople as his capital and permanent residence.

He lived there for a good portion of his later life. He rebuilt Trajan’s bridge

across the Danube, in hopes of reconquering

Dacia

, a province that had been abandoned under

Aurelian. In the late winter of 332, Constantine campaigned with the

Sarmatians

against the

Goths

. The weather and lack of food cost the

Goths dearly: reportedly, nearly one hundred thousand died before they submitted

to Rome. In 334, after Sarmatian commoners had overthrown their leaders,

Constantine led a campaign against the tribe. He won a victory in the war and

extended his control over the region, as remains of camps and fortifications in

the region indicate.Constantine resettled some Sarmatian exiles as farmers in

Illyrian and Roman districts, and conscripted the rest into the army.

Constantine took the title Dacicus maximus in 336.

Sickness and death

Constantine had known death would soon come. Within the Church of the Holy

Apostles, Constantine had secretly prepared a final resting-place for himself.It

came sooner than he had expected. Soon after the Feast of Easter 337,

Constantine fell seriously ill. He left Constantinople for the hot baths near

his mother’s city of Helenopolis (Altinova), on the southern shores of the Gulf

of İzmit. There, in a church his mother built in honor of Lucian the Apostle, he

prayed, and there he realized that he was dying. Seeking purification, he became

a catechumen

, and attempted a return to

Constantinople, making it only as far as a suburb of Nicomedia. He summoned the

bishops, and told them of his hope to be baptized in the

River Jordan

, where Christ was written to have

been baptized. He requested the baptism right away. The bishops, Eusebius

records, “performed the sacred ceremonies according to custom”. He chose the

Arianizing bishop

Eusebius of Nicomedia

, bishop of the

city

where he lay dying, as his baptizer. In

postponing his baptism, he followed one custom at the time which postponed

baptism until after infancy. Constantine died soon after at a suburban villa

called Achyron, on the last day of the fifty-day festival of Pentecost directly

following Pascha (or Easter), on 22 May 337.

Following his death, his body was transferred to Constantinople and buried in

the

Church of the Holy Apostles

there. He was

succeeded by his three sons born of Fausta,

Constantine II

,

Constantius II

and

Constans

. A number of relatives were killed by

followers of Constantius, notably Constantine’s nephews

Dalmatius

(who held the rank of Caesar) and

Hannibalianus

, presumably to eliminate possible

contenders to an already complicated succession. He also had two daughters,

Constantina

and

Helena

, wife of

Emperor Julian

.

Legacy

The Byzantine Empire considered Constantine its founder and the

Holy Roman Empire

reckoned him among the

venerable figures of its tradition. In the later Byzantine state, it had become

a great honor for an emperor to be hailed as a “new Constantine”. Ten emperors,

including the last emperor of Byzantium, carried the name. Most Eastern

Christian churches consider Constantine a saint (Άγιος Κωνσταντίνος, Saint

Constantine). In the Byzantine Church he was called isapostolos

(Ισαπόστολος Κωνσταντίνος) —an

equal of the Apostles

.

Niš airport

is named Constantine the Great in

honor of his birth in Naissus.

|