|

Greek Ruler of

Macedonian Kingdom

King Demetrius I Poliorcetes –

294-288 B.C.

Bronze 15mm (3.36 grams) Struck 294-288 B.C.

Reference: Sear 6775; Newell 20

Head of Demetrius right, wearing crested Corinthian helmet ornamented with

bull’s horn.

Prow of galley right; BA above, monogram beneath.

Son of Antigonos the One-eyed, Demetrios Poliorketes (the ‘Besiger’) was a

romantic chracter who pursued a most colorful career spanning more than three

decades. In his earlier years he assisted his father, whose power was centered

in Asia Minor, and in 306 he achieved a great naval victory over Ptolemy of

Egypt, in the batte f Salamis, off the coast of Cyprus. After many vicissituedes

he seized the Macedonian throne in 294, although he reigned for only six years

the dyansty which he founded lasted unil the end of the Macedonian Kingdom. He

died as a captive in Syria in 283 B.C.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Demetrius I (337-283BC), called Poliorcetes “The Besieger”), son of

Antigonus I Monophthalmus

and

Stratonice

, was a king of

Macedon

(294-288 BC). He belonged to the

Antigonid dynasty

.

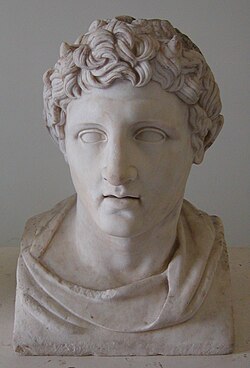

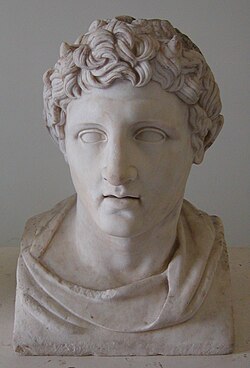

Marble bust of Demetrius I Poliorcetes. Roman copy from 1st century AD of a Greek original from 3rd century BC

Biography

At the age of twenty-two he was left by his father to defend

Syria

against

Ptolemy

the son of

Lagus

; he was

totally defeated in

Battle of Gaza

, but soon partially repaired his loss by a victory in the

neighbourhood of Myus

.

In the spring of 310, he was soundly defeated when he tried to expel

Seleucus I Nicator

from

Babylon

; his

father was defeated in the autumn. As a result of this

Babylonian War

, Antigonus lost almost two thirds of his empire: all eastern

satrapies became Seleucus’.

After several campaigns against Ptolemy on the coasts of

Cilicia

and

Cyprus

,

Demetrius sailed with a fleet of 250 ships to

Athens

. He

freed the city from the power of

Cassander

and Ptolemy, expelled the garrison which had been stationed there under

Demetrius of Phalerum

, and besieged and took

Munychia

(307 BC). After these victories he was worshipped by the Athenians

as a

tutelary

deity under the title of Soter (“Preserver”).

In the campaign of 306 BC against Ptolemy he defeated

Menelaus

, Ptolemy’s brother, in the naval

Battle of Salamis

, completely destroying the naval power of

Egypt

. In 305 BC,

now bearing the title of king bestowed upon him by his father, he endeavoured to

punish the Rhodians

for having deserted his cause; his ingenuity in devising new

siege engines

in his unsuccessful attempt to reduce the capital gained him

the title of Poliorcetes. Among his creations were a

battering ram

180 feet (55 m) long, requiring 1000 men to operate it; and a

wheeled siege tower

named “Helepolis”

(or “Taker of Cities”) which stood 125 feet (38 m) tall and 60 feet (18 m) wide,

weighing 360,000 pounds.

In 302 BC he returned a second time to Greece as liberator, and reinstated

the

Corinthian League

. But his licentiousness and extravagance made the

Athenians long for the government of Cassander. Among his outrages was his

courtship of a young boy named Democles the Handsome. The youth kept on refusing

his attention but one day found himself cornered at the baths. Having no way out

and being unable to physically resist his suitor, he took the lid off the hot

water cauldron and jumped in. His death is seen as a mark of honor for himself

and his country. In another instance, he waived a fine of 50 talents imposed on

a citizen in exchange for the favors of Cleaenetus, that man’s son.[1]

He also sought the attention of Lamia, a Greek courtesan. She demanded a price

of 250 talents. He put a tax on soap to raise the money.[2]

He also roused the jealousy of

Alexander

‘s Diadochi

;

Seleucus

, Cassander and

Lysimachus

united to destroy him and his father. The hostile armies met at the

Ipsus

in Phrygia

(301 BC). Antigonus was killed, and Demetrius, after sustaining

severe losses, retired to

Ephesus

. This

reversal of fortune stirred up many enemies against him�the Athenians refused

even to admit him into their city. But he soon afterwards ravaged the territory

of Lysimachus

and effected a reconciliation with Seleucus, to whom he gave his

daughter

Stratonice

in marriage. Athens was at this time oppressed by the tyranny of

Lachares

– a popular leader who made himself supreme in Athens in 296 BC –

but Demetrius, after a protracted blockade, gained possession of the city (294

BC) and pardoned the inhabitants for their misconduct in 301.

In the same year he established himself on the throne of Macedonia by

murdering

Alexander V

, the son of Cassander. In 291 BC he married

Lanassa

, the former wife of

Pyrrhus

. But his new position as ruler of Macedonia was continually

threatened by Pyrrhus, who took advantage of his occasional absence to ravage

the defenceless part of his kingdom (Plutarch,

Pyrrhus, 7 if.); at length, the combined forces of Pyrrhus, Ptolemy and

Lysimachus, assisted by the disaffected among his own subjects, obliged him to

leave Macedonia in 288 BC.

He passed into Asia and attacked some of the provinces of Lysimachus with

varying success. Famine and pestilence destroyed the greater part of his army,

and he solicited Seleucus’ support and assistance. But before he reached Syria

hostilities broke out, and after he had gained some advantages over his

son-in-law, Demetrius was totally forsaken by his troops on the field of battle

and surrendered to Seleucus.

His son

Antigonus

offered all his possessions, and even his own person, in order to

procure his father’s liberty. But all proved unavailing, and Demetrius died

after a confinement of three years (283 BC). His remains were given to Antigonus

and honoured with a splendid funeral at

Corinth

.

His descendants remained in possession of the Macedonian throne till the time

of

Perseus

, when Macedon was conquered by the

Romans

in 168 BC.

Literary references

Demetrius appears (under the Greek form of his name, Demetrios) in

L. Sprague de Camp

‘s historical novel,

The Bronze God of Rhodes

, which largely concerns itself with his siege

of Rhodes.

Alfred Duggan’s novel Elephants and Castles provides a lively

fictionalised account of his life.

A galley is a type of

ship propelled by

rowers

that originated in the

Mediterranean region

and was used for

warfare

,

trade

and

piracy

from the first millennium BC. Galleys

dominated

naval warfare

in the

Mediterranean Sea

from the 8th century BC until

development of advanced sailing warships in the 17th century. Galleys fought in

the wars of Assyria

, ancient

Phoenicia

,

Greece

,

Carthage

and

Rome

until the 4th century AD. After the fall

of the

Western Roman Empire

galleys formed the

mainstay of the

Byzantine navy

and other navies of successors

of the Roman Empire, as well as new

Muslim

navies. Medieval Mediterranean states,

notably the Italian maritime republics, including

Venice

,

Pisa

, and

Genoa

, relied on them as the primary warships

of their fleets until the late 16th century, when they were displaced by

broadside

sailing warships. Galleys continued

to be applied in minor roles in the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea even after

the invention of

steam propelled

ships in the early 19th

century.

The galley engagements at

Actium

and

Lepanto

are among the greatest

naval battles

in history.

Definition and

terminology

The term “galley” derives from the

medieval Greek

galea, a type of small

Byzantine

galley.[1]

The origin of the Greek word is unclear but could possibly be related to

galeos, “dog-fish; small shark”.[2]

The term has been attested in English from c. 1300[3]

and has been used in most European languages from around 1500 as a general term

for oared war vessels, especially those used in the Mediterranean from the late

Middle Ages and onwards.[4]

It is only since the 16th century that a unified galley concept has been in

use. Before that, and particularly in antiquity, there was a wide variety of

terms used for different types of galleys. In modern historical literature,

“galley” is occasionally used as a general term for various oared vessels,

though the “true” galley is defined as the ships belonging to the Mediterranean

tradition.[5]

Archaeologist

Lionel Casson

has on occasion used “galley” to

describe all North European shipping in the early and high Middle Ages,

including Viking

merchants and even their famous

longships

.[6]

In the late 18th century, the “galley” was in some contexts used to describe

oared gun-armed vessels which did not fit into the category of the classic

Mediterranean-type galleys. During the

American Revolutionary War

and the wars against

France and Britain the US Navy built vessels that were described as “row

galleys” or simply “galleys”, though they actually were variants of

brigantines

or Baltic

gunboats

.[7]

The description was more a characterization of their military role, and

partially due to technicalities in the administration and naval financing.[8]

Origins

Among the earliest known watercraft were

canoes

made from hollowed-out logs, the

earliest ancestors of galleys. Their narrow hulls required them to be

paddled

in a fixed sitting position facing

forwards, a less efficient form of propulsion than rowing with proper

oars, facing backwards. Sea-going paddled craft have been attested by

finds of terracotta sculptures and lead models in the region of the

Aegean Sea

from the 3rd millennium BC. However,

archaeologists believe that the

Stone Age

colonization of islands in the

Mediterranean around 8,000 BC required fairly large, seaworthy vessels that were

paddled and possibly even equipped with sails.[9]

The first evidence of more complex craft that are considered to prototypes for

later galleys comes from

Ancient Egypt

during the

Old Kingdom

(c. 2700-2200 BC). Under the rule

of pharaoh

Pepi I

(2332-2283 BC) these vessels were used

to transport troops to raid settlements along the

Levantine

coast and to ship back slaves and

timber.[10]

During the reign of

Hatshepsut

(c. 1479-57 BC), Egyptian galleys

traded in luxuries on the

Red Sea

with the enigmatic

Land of Punt

, as recorded on wall paintings at

the

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

at

Deir el-Bahari

.[11]

Assyrian

warship, a

bireme

with pointed bow. 700 BC

Shipbuilders, probably

Phoenician

, a seafaring people who lived on the

southern and eastern coasts of the Mediterranean, were the first to create the

two-level galley that would be widely known under its Greek name, biērēs,

or bireme

.[12]

Even though the

Phoenicians

were among the most important naval

civilizations in early

Antiquity

, little detailed evidence have been

found concerning the types of ships they used. The best depictions found so far

have been small, highly stylized images on seals which depict crescent-shape

vessels equipped with one mast and banks of oars. Colorful frescoes on the

Minoan

settlement on

Santorini

(c. 1600 BC) show more detailed

pictures of vessels with ceremonial tents on deck in a procession. Some of these

are rowed, but others are paddled with men laboriously bent over the railings.

This has been interpreted as a possible ritual reenactment of more ancient types

of vessels, alluding to a time before rowing was invented, but little is

otherwise known about the use and design of Minoan ships.[13]

Military history

The first Greek galleys appeared around the second half of the 2nd millennium

BC. In the epic poem, the

Iliad

, set in the 12th century BC, galleys

with a single row of oarsmen were used primarily to transport soldiers to and

from various land battles.[14]

The first recorded naval battle, the

battle of the Delta

between Egyptian forces

under Ramesses III

and the enigmatic alliance known

as the Sea Peoples

, occurred as early as 1175 BC. It

is the first known engagement between organized armed forces, using sea vessels

as weapons of war, though primarily as fighting platforms. It was distinguished

by being fought against an anchored fleet close to shore with land-based archer

support.[15]

A reconstruction of an ancient Greek galley squadron based on images

of modern replica

Olympias

The development of the

ram

sometime before the 8th century BC changed

the nature of naval warfare, which had until then been a matter of boarding and

hand-to-hand fighting. With a heavy projection at the foot of the

bow

, sheathed with metal, usually

bronze

, a ship could render an enemy galley

useless by breaking its side planking. The relative speed and nimbleness of

ships became important, since a slower ship could be outmaneuvered and disabled

by a faster one. Early designs had only one row of rowers that sat in undecked

hulls, rowing against tholes

, or oarports, placed directly along the

railings. The practical upper limit for wooden constructions fast and

maneuverable enough for warfare was around 25-30 oars per side. By adding

another level of oars, a development that occurred no later than c. 750 BC, the

galley could be made shorter with as many rowers, while making them strong

enough to be effective ramming weapons.[16]

Early galleys usually had between 15 and 30 pairs of oars and were called

triaconters

or

penteconters

, literally “thirty-” and

“fifty-oared”, respectively. By the 8th century BC, the Phoenecians had added a

second row of oars to these ships, creating the bireme. Soon after, a third row

of oars was added by the addition of an

outrigger

to the hull of a bireme, a projecting

construction that allowed for more room for the projecting oars. These new

galleys were called triÄ“rÄ“s (“three-fitted”) in Greek. The

Romans

later called this design the triremis,

trireme

, the name it is today best known under.

It has been hypothesized that early types of triremes existed in 701 BC, but the

earliest positive literary reference dates to 542 BC.[17]

According to the Greek historian

Herodotos

, the first ramming action occurred in

535 BC when 60

Phocaean

penteconters fought 120

Etruscan

and

Carthaginian

ships. On this occasion it was

described as an innovation that allowed Phocaeans to defeat a larger force.[18]

The emergence of more advanced states and intensified competition between

them spurred on the development of advanced galleys with multiple banks of

rowers. During the middle of the first millennium BC, the Mediterranean powers

developed successively larger and more complex vessels, the most advanced being

the classical trireme

with up to 170 rowers. Triremes fought

several important engagements in the naval battles of the

Greco-Persian Wars

(502–449 BC) and the

Peloponnesian War

(431-404 BC), including the

battle of Aegospotami

in 405 BC, which sealed

the defeat of the

Athenian Empire

by

Sparta

and her allies. The trireme was an

advanced ship that was expensive to build and to maintain due its large crew. By

the 5th century, advanced war galleys had been developed that required sizable

states with an advanced economy to build and maintain. It was associated with

the latest in warship technology around the 4th century BC and could only be

employed by a sizeable state with an advanced economy and administration. They

required considerable skill to row and oarsmen were mostly free citizens that

had a lifetime of experience at the oar.[19]

Greeks and Phoenicians

Early Greek vessels had few

navigational

tools. Most ancient and medieval

shipping remained in sight of the coast for ease of navigation, safety, trading

opportunities, and coastal currents and winds that could be used to work against

and around prevailing winds. It was more important for galleys than sailing

ships to remain near the coast because they needed more frequent re-supply of

fresh water for their large, sweating, crews and were more vulnerable to storms.

Unlike ships primarily dependent on sails, they could use small bays and beaches

as harbors, travel up rivers, operate in water only a meter or so deep, and be

dragged overland to be launched on lakes, or other branches of the sea. This

made them suitable for launching attacks on land. In antiquity a famous

portage

was the

diolkos

of Corinth. In 429 BC (Thucydides

2.56.2), and probably earlier (Herodotus 6.48.2, 7.21.2, 7.97), galleys were

adapted to carry horses to provide cavalry support to troops also landed by

galleys.

The compass

did not come into use for navigation

until the 13th century AD, and

sextants

,

octants

, accurate

marine chronometers

, and the mathematics

required to determine

longitude

and

latitude

were developed much later. Ancient

sailors navigated by the sun and the prevailing wind[citation

needed]. By the

first millennium BC

they had started using the

stars to navigate at night. By 500 BC they had the

sounding lead

(Herodotus 2.5).

Galleys were hauled out of the water whenever possible to keep them dry,

light and fast and free from worm, rot and seaweed. Galleys were usually

overwintered in ship sheds which left distinctive archeological remains.[20]

There is evidence that the hulls of the Punic wrecks were sheathed in lead.

Building an efficient galley posed technical problems. The faster a ship

travels, the more energy it uses. Through a process of trial and error, the

unireme or monoreme � a galley with one row of oars on each side � reached the

peak of its development in the

penteconter

, about 38 m long, with 25 oarsmen

on each side. It could reach 9 knots (18 km/h), only a knot or so slower than

modern rowed racing-boats. To maintain the strength of such a long craft

tensioned cables were fitted from the bow to the stern; this provided rigidity

without adding weight. This technique kept the joints of the hull under

compression – tighter, and more waterproof. The tension in the modern trireme

replica anti-hogging

cables was 300 kN (Morrison p198).

Hellenistic era and rise of the Republic

As civilizations around the Mediterranean grew in size and complexity, both

their navies and the galleys that made up their numbers became successively

larger. The basic design of two or three rows of oars remained the same, but

more rowers were added to each oar. The exact reasons are not known, but are

believed to have been caused by addition of more troops and the use of more

advanced ranged weapons on ships, such as

catapults

. The size of the new naval forces

also made it difficult to find enough skilled rowers for the one-man-per-oar

system of the earliest

triremes

. With more than one man per oar, a

single rower could set the pace for the others to follow, meaning that more

unskilled rowers could be employed.[21]

The successor states of

Alexander the Great

‘s empire built galleys that

were like triremes or biremes in oar layout, but manned with additional rowers

for each oar. The ruler

Dionysius I of Syracuse

(ca. 432–367 BC) is

credited with pioneering the “five” and “six”, meaning five or six rows of

rowers plying two or three rows of oars.

Ptolemy II

(283-46 BC) is known to have built a

large fleet of very large galleys with several experimental designs rowed by

everything from 12 up to 40 rows of rowers, though most of these are considered

to have been quite impractical. Fleets with large galleys were put in action in

conflicts such as the

Punic Wars

(246-146) between the

Roman republic

and

Carthage

, which included massive naval battles

with hundreds of vessels and tens of thousands of soldiers, seamen and rowers.[22]

Roman Imperial era

Depictions of two compact liburnians used by the Romans in their

campaigns against the Dacians

in

the early 2nd century AD; reliefs from

Trajan’s Column

, c. 113 AD.

The

battle of Actium

in 31 BC between the forces of

Augustus

and

Mark Antony

marked the peak of the Roman fleet

arm. After Augustus’ victory at Actium, most of the Roman fleet was dismantled

and burned. The

Roman civil wars

were fought mostly by land

forces, and from the 160s until the 4th century AD, no major fleet actions were

recorded. During this time, most of the galley crews were disbanded or employed

for entertainment purposes in

mock battles

or in handling the sail-like

sun-screens in the larger Roman arenas. What fleets remained were treated as

auxiliaries of the land forces, and galley crewmen themselves called themselves

milites, “soldiers”, rather than nautae, “sailors”.[23]

Instead, the Roman galley fleets were turned into provincial patrol forces that

were smaller and relied largely on liburnians, compact biremes with 25

pairs of oars. These were named after an

Illyrian tribe

known by Romans for their sea

roving practices, and these smaller craft were based on, or inspired by, their

vessels of choice. The liburnians and other small galleys patrolled the rivers

of continental Europe and reached as far as the Baltic, where they were used to

fight local uprisings and assist in checking foreign invasions. The Romans

maintained numerous bases around the empire: along the rivers of Central Europe,

chains of forts along the northern European coasts and the British Isles,

Mesopotamia and North Africa, including

Trabzon

, Vienna, Belgrade, Dover,

Seleucia

and

Alexandria

. Few actual galley battles in the

provinces are found in records, but one action in 70 AD at the uncertain

location of the “Island of the Batavians” during the

Batavian Rebellion

was noted, and featured a

trireme as the Roman flagship.[24]

The last provincial fleet, the classis Britannica, was reduced by the

late 200s, though there was a minor upswing under the rule of

Constantine

(272–337). His rule also saw the

final major naval battle of the Roman Empire, the

battle of Adrianople

of 324. Some time after

Adrianople, the classical trireme fell out of use, and was eventually forgotten.[25]

Middle Ages

A 13th century war galley depicted in a Byzantine-style fresco.

Late medieval

maritime warfare was divided in

two distinct regions. In the Mediterranean galleys were used for raiding along

coasts, and in the constant fighting for naval bases. In the Atlantic and Baltic

there was greater focus on sailing ships that were used mostly for troop

transport, with galleys providing fighting support.[26]

Galleys were still widely used in the north and were the most numerous warships

used by Mediterranean powers with interests in the north, especially the French

and Iberian kingdoms.[27]

A transition from galley to sailing vessels as the most common types of warships

began in the

high Middle Ages

(c. 11th century). Large

high-sided sailing ships had always been formidable obstacles for galleys. To

low-freeboard oared vessels, the bulkier sailing ships like the

carrack

and the

cog

acted almost like floating fortresses,

being difficult to board and even harder to capture. Galleys remained useful as

warships throughout the Middle Ages since they had the ability to maneuver in a

way that sailing vessels of the time were completely incapable of. Sailing ships

of the time had only one mast, usually with just one large square sail, which

made them cumbersome to steer and virtually impossible to sail in the wind

direction. This allowed the galleys great freedom of movement along coasts for

raiding and landing troops.[28]

In the eastern Mediterranean, the

Byzantine Empire

struggled with the incursion

from invading Muslim Arabs from the 7th century, leading to fierce competition,

a buildup of fleet, and war galleys of increasing size. Soon after conquering

Egypt and the Levant, the Arab rulers built ships highly similar to Byzantine

dromons

with the help of local

Coptic

shipwrights former Byzantine naval

bases.[29]

By the 9th century, the struggle between the Byzantines and Arabs had turned the

Eastern Mediterranean into a no man’s land for merchant activity. In the 820s

Crete

was captured by Andalusian Muslims

displaced by a failed revolt against the

Emirate of Cordoba

, turning the island into a

base for (galley) attacks on Christian shipping until the island was recaptured

by the Byzantines in 960.[30]

In the western Mediterranean and Atlantic, the division of the

Carolingian Empire

in the late 9th century

brought on a period of instability, meaning increased piracy and raiding in the

Mediterranean, particularly by newly-arrived Muslim invaders. The situation was

worsened by raiding Scandinavian

Vikings

who used

longships

, vessels that in many ways were very

close to galleys in design and functionality and also employed similar tactics.

To counter the threat, local rulers began to build large oared vessels, some

with up to 30 pairs of oars, that were larger, faster and with higher sides than

Viking ships.[31]

Scandinavian expansion, including incursions into the Mediterranean and attacks

on both Muslim Iberia and even Constantinople itself, subsided by the mid-11th

century. By this time, greater stability in merchant traffic was achieved by the

emergence of Christian kingdoms such as those of France, Hungary and Poland.

Around the same time, Italian port towns and city states, like

Venice

,

Pisa

and

Amalfi

, rose on the fringes of the Byzantine

Empire as it struggled with eastern threats.[32]

During the 13th and 14th century, the galley evolved into a design that was

to remain essentially the same until it was phased out in the early 19th

century. The new type of galley descended from the ships used by Byzantine and

Muslim fleets in the early Middle Ages. These were the mainstay of all Christian

powers until the 14th century, including the great maritime republics of Genoa

and Venice, the Papacy, the Hospitallers, Aragon and Castile, as well as by

various

pirates

and

corsairs

. The overall term used for these types

of vessels was gallee sottili (“slender galleys”). The later

Ottoman navy

used similar designs, but they

were generally faster under sail, and smaller, but slower under oars.[33]

Galley designs were intended solely for close action with hand-held weapons and

projectile weapons like bows and crossbows. In the 13th century the Iberian

kingdom of Aragon

built several fleet of galleys with high

castles, manned with Catalan crossbowman, and regularly defeated numerically

superior

Angevin

forces.[34]

During the 14th century, galleys began to be equipped with cannons of various

sizes, mostly smaller ones at first, but also larger bombardas on vessels

belonging to

Alfonso V of Aragon

.

The

transition to sailing ships

As early as 1304 the type of ship required by the Danish defence organization

changed from galley to

cog

, a flat-bottomed sailing ship.[35]

During the early 15th century, sailing ships began to dominate naval warfare

in northern waters. While the galley still remained the primary warship in

southern waters, a similar transition had begun also among the Mediterranean

powers. A

Castilian

naval raid on the island of

Jersey

in 1405 became the first recorded battle

battle where a Mediterranean power employed a naval force consisting mostly of

cogs or nefs

, rather than the oared-powered galleys.

The

battle of Gibraltar

between Castile and

Portugal in 1476 was another important sign of change; it was the first recorded

battle where the primary combatants were full-rigged ships armed with

wrought-iron guns on the upper decks and in the waists, foretelling of the slow

decline of the war galley.[36]

Early modern period

Painting of the

battle of Haarlemmermeer

of 1573 by

Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom

. Note the

use of small sailing vessels and galleys on both sides.

From around 1450, three major naval powers established a dominance over

different parts of the Mediterranean using galleys as their primary weapons at

sea: the Ottomans in the east, Venice in the center and

Habsburg Spain

in the west.[37]

The core of their fleets were concentrated in the three major, wholly dependable

naval bases in the Mediterranean:

Constantinople

,

Venice

and

Barcelona

.[38]

Naval warfare in the 16th century Mediterranean was fought mostly on a smaller

scale, with raiding and minor actions dominating. Only three truly major fleet

engagements were actually fought in the 16th century: the battles of

Preveza

in 1538,

Djerba

in 1560 and

Lepanto

in 1571. Lepanto became the last large

all-galley battle ever, and was also one of the largest battle in terms of

participants anywhere in early modern Europe before the

Napoleonic Wars

.[39]

Occasionally the Mediterranean powers employed galley forces for conflicts

outside of the Mediterranean. Spain sent galley squadrons to the Netherlands

during the later stages of the

Eighty Years’ War

which successfully operated

against Dutch forces in the enclosed, shallow coastal waters. From the late

1560s, galleys were also used to transport silver to Genoese bankers to finance

Spanish troops against the Dutch uprising.[40]

Galleasses and galleys were part of an invasion force of over 16,000 men that

conquered the Azores

in 1583. Around 2,000 galley rowers were

on board ships of the famous 1588

Spanish Armada

, though few of these actually

made it to the battle itself.[41]

Outside of European and Middle Eastern waters, Spain built galleys to deal with

pirates and privateers in both the Caribbean and the Philippines.[42]

Ottoman galleys contested the Portuguese intrusion in the Indian Ocean in the

16th century, but failed against the high-sided, massive Portuguese carracks in

open waters.[43]

Galleys had been synonymous with warships in the Mediterranean for at least

2,000 years, and continued to fulfill that role with the invention of gunpowder

and heavy artillery. Though early 20th century historians often dismissed the

galleys as hopelessly outclassed with the first introduction of naval artillery

on sailing ships,[44]

it was the galley that was favored by the introduction of heavy naval guns.

Galleys were a more “mature” technology with long-established tactics and

traditions of supporting social institutions and naval organizations. In

combination with the intensified conflicts this led to a substantial increase in

the size of galley fleets from c. 1520-80, above all in the Mediterranean, but

also in other European theatres.[45]

Galleys and similar oared vessels remained uncontested as the most effective

gun-armed warships in theory until the 1560s, and in practice for a few decades

more, and were actually considered a grave risk to sailing warships.[46]

They could effectively fight other galleys, attack sailing ships in calm weather

or in unfavorable winds (or deny them action if needed) and act as floating

siege batteries. They were also unequaled in their amphibious capabilities, even

at extended ranges, as exemplified by French interventions as far north as

Scotland in the mid-16th century.[47]

Heavy artillery on galleys was mounted in the bow which fit conveniently with

the long-standing tactical tradition of attacking head-on and bow-first. The

ordnance on galleys was heavy from its introduction in the 1480s, and capable of

quickly demolishing the high, thin medieval stone walls that still prevailed in

the 16th century. This temporarily upended the strength of older seaside

fortresses, which had to be rebuilt to cope with gunpowder weapons. The addition

of guns also improved the amphibious abilities of galleys as they could assault

supported with heavy firepower, and could be even more effectively defended when

beached stern-first.[48]

An accumulation and generalizing of bronze cannons and small firearms in the

Mediterranean during the 16th century increased the cost of warfare, but also

made those dependent on them more resilient to manpower losses. Older ranged

weapons, like bows or even crossbows, required considerable skill to handle,

sometimes a lifetime of practice, while gunpowder weapons required considerable

less training to use successfully.[49]

According to a highly influential study by military historian John F. Guilmartin,

this transition in warfare, along with the introduction of much cheaper cast

iron guns in the 1580s, proved the “death knell” for the war galley as a

significant military vessel.[50]

Gunpowder weapons began to displace men as the fighting power of armed forces,

making individual soldiers more deadly and effective. As offensive weapons,

firearms could be stored for years with minimal maintenance and did not require

the expenses associated with soldiers. Manpower could thus be exchanged for

capital investments, something which benefited sailing vessels that were already

far more economical in their use of manpower. It also served to increase their

strategic range and to out-compete galleys as fighting ships.[51]

The North

The Galley Subtle, one of the very few Mediterranean-style

galleys employed by the English. Illustration from the

Anthony Roll

, c. 1546.

Oared vessels remained in use in northern waters for a long time, though in

subordinate role and in particular circumstances. During the

Dutch Revolt

(1566–1609) against the Habsburg

empire, both the Spanish and Dutch (including those who remained loyal to the

Habsburgs) employed galleys in amphibious operations in shallow waters where

deep-draft sailing vessels could not enter.[52]

In the Italian Wars

, French galleys brought up from

the Mediterranean to the Atlantic posed a serious threat to the early English

Tudor navy

during coastal operations. The

response came in the building of a considerable fleet of oared vessels,

including hybrids with a complete three-masted rig, as well as a

Mediterranean-style galleys (that were even attempted to be manned with convicts

and slaves).[53]

Under king

Henry VIII

, the English navy used several kinds

of vessels that were adapted to local needs. English galliasses (very

different from the Mediterranean vessel of

of the same name

) were employed to cover the

flanks of larger naval forces while pinnaces and rowbarges were

used for scouting or even as a backup for the

longboats

and tenders for the larger sailing

ships.[54]

While galleys were too vulnerable to be used in large numbers in the open

waters of the Atlantic, they were well-suited for use in much of the Baltic Sea

by Denmark, Sweden, Russia and some of the Central European powers with ports on

the southern coast. There were two types of naval battlegrounds in the Baltic.

One was the open sea, suitable for large sailing fleets; the other was the

coastal areas and especially the chain of small islands and archipelagos that

ran almost uninterrupted from Stockholm to the Gulf of Finland. In these areas,

conditions were often too calm, cramped and shallow for sailing ships, but they

were excellent for galleys and other oared vessels.[55]

Galleys of the Mediterranean type were first introduced in the

Baltic Sea

around the mid-16th century as

competition between the Scandinavian states of Denmark and Sweden intensified.

The Swedish galley fleet was the largest outside of the Mediterranean, and

served as an auxiliary branch of the army. Very little is known about the design

of Baltic galleys, except that they were overall smaller than in the

Mediterranean and they were rowed by army soldiers rather than convicts or

slaves.[56]

Mediterranean decline

Atlantic style warfare based on heavily armed sailing ships began to change

the nature of naval warfare in the Mediterranean in the 17th century. In 1616, a

small squadron of five

galleons

and a

patache

was used to cruise the eastern

Mediterranean and defeated a fleet of fifty five galleys at the

battle of Cape Celidonia

. By 1650, war galleys

were used primarily in the wars between Venice and the Ottoman Empire in their

struggle for strategic island and coastal trading bases and until the 1720s by

France and Spain but for largely amphibious and cruising operation, not for

large fleet battles. Even a purely Mediterranean power like Venice began to

construct sail only warships in the latter part of the century. Christian and

Muslim corsairs had been using galleys in sea roving and in support of the major

powers in times of war, but largely replaced them with

xebecs

, various sail/oar hybrids, and a few

remaining light galleys in the early 17th century.[57]

Spain still waged classical amphibious galley warfare in the 1640s by supplying

troops in Tarragona in its war against France.[58]

No large all galley battles were fought after the gigantic clash at Lepanto in

1571, and galleys were mostly used as cruisers or for supporting sailing

warships as a rearguard in fleet actions, similar to the duties performed by

frigates

outside of the Mediterranean.[57]

They could assist damaged ships out of the line, but generally only in very calm

weather, as was the case at the

battle of Malaga

in 1704.[59]

For small states and principalities as well as groups of private merchants,

galleys were more affordable than large and complex sailing warships, and were

used as defense against piracy.[60]

The largest galley fleets in the 17th century were operated by the two major

Mediterranean powers,

France

and

Spain

. France had by the 1650s become the most

powerful state in Europe, and expanded its galley forces under the rule of the

absolutist “Sun King”

Louis XIV

. In the 1690s the

French Galley Corps

reached its all-time peak

with more than 50 vessels manned by over 15,000 men and officers, becoming the

largest galley in the world at the time.[61]

Though there was intense rivalry between France and Spain, not a single galley

battle occurred between the two great powers, and virtually no battles between

other nations either.[62]

During the

War of the Spanish Succession

, French galleys

were involved in actions against

Antwerp

and

Harwich

,[52]

but due to the intricacies of alliance politics there were never any

Franco-Spanish galley clashes. In the first half of the 18th century, the other

major naval powers in North Africa, the

Order of Saint John

and the

Papal States

all cut down drastically on their

galley forces.[63]

Despite the lack of action, the French Galley Corps received vast resources

(20-25% of the French naval expenditures) during the last decades of the 17th

centuries and was maintained as a functional fighting force right up until its

abolishment in 1748. Its primary function became to symbolize the prestige of

Louis XIV’s hard-line absolutist ambitions by patrolling the Mediterranean to

force ships of other states to salute the King’s banner, convoying ambassadors

and cardinals, and obediently participating in naval parades and royal

pageantry.[64]

The last recorded battle in the Mediterranean where galleys played a

significant part was at

Matapan

in 1717, between the Ottomans and

Venice and its allies, though they had little influence on the final outcome.

Few large-scale naval battles were fought in the Mediterranean throughout most

of the remainder of the 18th century. The Tuscan galley fleet was dismantled

around 1718, Naples had only four old vessels by 1734 and the French Galley

Corps had ceased to exist as an independent arm in 1748. Venice, the Papal

States and the Knights of Malta were the only state fleets that maintained

galleys, though in nothing like their previous quantities.[65]

By 1790, there were less than 50 galleys in service among all the Mediterranean

powers, half of which belonged to Venice.[66]

Baltic revival

The

second battle of Svensksund

in 1790

between the Swedish and Russian navies was the last major naval

battle between forces that included large numbers of galleys and

other oared vessels.

Galleys were introduced to the

Baltic Sea

in the 16th century but the details

of their designs are lacking due to the absence of records. They might have been

built in a more regional style, but the only known depiction from the time shows

a typical Mediterranean vessel. There is conclusive evidence that Denmark became

the first Baltic power to build classic Mediterranean-style galleys in the

1660s, though they proved to be generally too large to be useful for use in the

shallow waters of the Baltic archipelagos. Sweden and especially Russia began to

launch galleys and various rowed vessels in great numbers during the

Great Northern War

in the first two decades of

the 18th century.[67]

Sweden was late in the game when it came to building an effective oared fighting

fleet while the Russian galley forces under tsar

Peter I

developed into a supporting arm for the

sailing navy, as well as a well-functioning auxiliary of the army which

infiltrated and conducted numerous raids on the eastern Swedish coast in the

1710s.[68]

Sweden and Russia became the two main competitors for Baltic dominance in the

18th century, and built the largest galley fleets in the world at the time. They

were used for amphibious operations in Russo-Swedish wars of

1741-43

and

1788-90

. The last galleys ever constructed were

built in 1796 by Russia, and remained in service well into the 19th century, but

saw little action.[69]

The last time galleys were deployed in action was when the Russian navy attacked

Ã…bo (Turku)

in 1854 as part of the

Crimean War

.[70]

Trade

In the earliest days of the galley, there was no clear distinction between

galleys of trade and war other than their actual usage. River boats plied the

waterways of ancient Egypt during the Old Kingdom (2700-2200 BC) and sea-going

galley-like vessels were recorded bringing back luxuries from across the Red Sea

in the reign of pharaoh

Hatshepsu

(c. 1479-1457). Fitting rams to the

bows of vessels sometime around the 8th century BC resulted in a distinct split

in the design of warships, and set trade vessels apart, at least when it came to

use in naval warfare. The Phoenicians used galleys for transports that were less

elongated, carried fewer oars and relied more on sails. Carthaginian galley

wrecks found off Sicily that date to the 3rd or 2nd century BC had a length to

breadth ratio of 6:1, proportions that fell between the 4:1 of sailing merchant

ships and the 8:1 or 10:1 of war galleys. Merchant galleys in the ancient

Mediterranean were intended as carriers of valuable cargo or perishable goods

that needed to be moved as safely and quickly as possible.[71]

Most of the surviving documentary evidence comes from Greek and Roman

shipping, though it is likely that merchant galleys all over the Mediterranean

were highly similar. In Greek they were referred to as histiokopos

(“sail-oar-er”) to reflect that they relied on both types of propulsion. In

Latin they were called actuaria (navis) (“ship that moves”) in Latin,

stressing that they were capable of making progress regardless of weather

conditions. As an example of the speed and reliability, during an instance of

the famous “Carthago

delenda est“-speech,

Cato the Elder

demonstrated the close proximity

of the Roman arch enemy Carthage by displaying a fresh fig to his audience that

he claimed was been picked in North Africa only three days past. Other cargoes

carried by galleys were honey, cheese, meat and live animals intended for

gladiator

combat. The Romans had several types

of merchant galleys that specialized in various tasks, out of which the

actuaria with up to 50 rowers was the most versatile, including the

phaselus (lit. “bean pod”) for passanger transport and the lembus, a

small-scale express carrier. Many of these designs continued to be used until

the Middle Ages.[72]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the early centuries AD, the old

Mediterranean economy collapsed and the volume of trade went down drastically.

Its eastern successor, the

Byzantine Empire

, neglected to revive overland

trade routes but was dependent on keeping the sea lanes open to keep the empire

together. Bulk trade fell around 600-750 while the luxury trade increased.

Galleys remained in service, but were profitable mainly in the luxury trade,

which set off their high maintenance cost.[73]

In the 10th century, there was a sharp increase in piracy which resulted in

larger ships with more numerous crews. These were mostly built by the growing

city-states of Italy which were emerging as the dominant sea powers, including

Venice

,

Genoa

and

Pisa. Inheriting the Byzantine ship designs, the new merchant galleys

were similar dromons

, but without any heavy weapons and both

faster and wider. They could be manned by crews of up to 1,000 men and were

employed in both trade and warfare. A further boost to the development of the

large merchant galleys was the upswing in Western European pilgrims traveling to

the Holy Land[74]

In Northern Europe, Viking longships and their derivations,

knarrs

, dominated trading and shipping, though

developed separately from the Mediterranean galley tradition. In the South

galleys continued to be useful for trade even as sailing vessels evolved more

efficient hulls and rigging; since they could hug the shoreline and make steady

progress when winds failed, they were highly reliable. The zenith in the design

of merchant galleys came with the state-owned great galleys of the

Venetian Republic

, first built in the 1290s.

These were used to carry the lucrative trade in luxuries from the east such as

spices, silks and gems. They were in all respects larger than contemporary war

galleys (up to 46 m) and had a deeper draft, with more room for cargo (140-250

t). With a full complement of rowers ranging from 150 to 180 men, all available

to defend the ship from attack, they were also very safe modes of travel. This

attracted a business of carrying affluent pilgrims to the Holy Land, a trip that

could be accomplished in as little 29 days on the route Venice-Jaffa,

despite landfalls for rest and watering or for respite from rough weather.[75]

From the first half of the 14th century the Venetian galere da mercato

(“merchantman galleys”) were being built in the shipyards of the state-run

Arsenal

as “a combination of state enterprise

and private association, the latter being a kind of consortium of export

merchants”, as Fernand Braudel described them.[76]

The ships sailed in convoy, defended by archers and slingsmen (ballestieri)

aboard, and later carrying cannons. In

Genoa

, the other major maritime power of the

time, galleys and ships in general were more produced by smaller private

ventures.

In the 14th and 15th centuries merchant galleys traded high-value goods and

carried passengers. Major routes in the time of the early Crusades carried the

pilgrim traffic to the Holy Land. Later routes linked ports around the

Mediterranean, between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea (a grain trade soon

squeezed off by the Turkish capture of Constantinople, 1453) and between the

Mediterranean and Bruges

� where the first Genoese galley arrived

at Sluys in 1277, the first Venetian galere in 1314� and

Southampton

. Although primarily sailing

vessels, they used oars to enter and leave many trading ports of call, the most

effective way of entering and leaving the

Lagoon of Venice

. The Venetian galera,

beginning at 100 tons and built as large as 300, was not the largest merchantman

of its day, when the Genoese

carrack

of the 15th century might exceed 1000

tons.[77]

In 1447, for instance, Florentine galleys planned to call at 14 ports on their

way to and from Alexandria.[78]

The availability of oars enabled these ships to navigate close to the shore

where they could exploit land and sea breezes and coastal currents, to work

reliable and comparatively fast passages against the prevailing wind. The large

crews also provided protection against piracy. These ships were very seaworthy;

a Florentine great galley left Southampton on 23 February 1430 and returned to

its port at Pisa in 32 days. They were so safe that merchandise was often not

insured (Mallet). These ships increased in size during this period, and were the

template from which the

galleass

developed.

Design

Illustration of an Egyptian rowed ship of c. 1250 BC. Due to a lack

of a proper keel

, the vessel has a

truss

, a thick cable along its

length, to prevent it from losing its shape.

Galleys have since their first appearance in ancient times been intended as

highly maneuverable vessels, independent of winds by being rowed, and usually

with a focus on speed under oars. The profile has therefore been that of a

markedly elongated hull with a ratio of breadth to length at the waterline of at

least 1:5, and in the case of ancient Mediterranean galleys as much as 1:10 with

a small draught, the measurement of how much of a ship’s structure that is

submerged under water. To make it possible to efficiently row the vessels, the

freeboard

, the height of the railing to the

surface of the water, was by necessity kept low. This gave oarsmen enough

leverage to row efficiently, but at the expense of seaworthiness. These design

characteristics made the galley fast and maneuverable, but more vulnerable to

rough weather.

On the funerary monument of the Egyptian king

Sahure

(2487–2475 BC) in

Abusir

, there are relief images of vessels with

a marked

sheer

(the curvature along its length) and

seven pairs of oars along its side, a number that was likely to have been merely

symbolical, and steering oars in the stern. They have one mast, all lowered and

vertical posts at stem and stern, with the front decorated with an

Eye of Horus

, the first example of such a

decoration. It was later used by other Mediterranean cultures to decorate sea

going craft in the belief that it helped to guide the ship safely to its

destination. These early galleys apparently lacked a

keel meaning they lacked stiffness along their length. Therefore they

had large cables connecting stem and stern resting on massive crutches on deck.

They were held in tension to avoid

hogging

, or bending the ship’s construction

upwards in the middle, while at sea.[10]

In the 15th century BC, Egyptian galleys were still depicted with the

distinctive extreme sheer, but had by then developed the distinctive

forward-curving stern decorations with ornaments in the shape of

lotus flowers

.[79]

They had possibly developed a primitive type of keel, but still retained the

large cables intended to prevent hogging.[11]

The design of the earliest oared vessels is mostly unknown and highly

conjectural. They likely used a

mortise

construction, but were sewn together

rather than pinned together with nails and dowels. Being completely open, they

were rowed (or even paddled) from the open deck, and likely had “ram entries”,

projections from the bow lowered the resistance of moving through water, making

them slightly more hydrodynamic. The first true galleys, the

triaconters

(“thirty-oarers”) and

penteconters

(“fifty-oarers”) were developed

from these early designs and set the standard for the larger designs that would

come later. They were rowed on only one level, which made them fairly slow,

likely only 5-5.5 knots. By the 8th century BC the first galleys rowed at two

levels had been developed, among the earliest being the two-level penteconters

which were considerably shorter than the one-level equivalents, and therefore

more maneuverable. They were an estimated 25 m in length and displaced 15 tonnes

with 25 pairs of oars. These could have reached an estimated top speed of up to

7.5 knots, making them the first genuine warships when fitted with bow rams.

They were equipped with a single

square sail

on mast set roughly halfway along

the length of the hull.[80]

Antiquity

The ram bow of the trireme

Olympias

, a modern full-scale

reconstruction of a classical Greek trireme.

By the 5th century BC, the first

triremes

were in use by various powers in the

eastern Mediterranean. It had now become a fully developed, highly specialized

vessel of war that was capable of high speeds and complex maneuvers. At nearly

40 m in length, displacing almost 50 tonnes, it was more than three times as

expensive than a two-level penteconter. A trireme also had an additional mast

with a smaller square sail placed near the bow.[81]

Up to 170 oarsmen sat on three levels with one oar each that varied slightly in

length. To accommodate three levels of oars, rowers sat staggered on three

levels. Arrangement of the three levels are believed to have varied, but the

most well-documented design made use of a projecting structure, or

outrigger

, where the

oarlock

in the form of a thole pin was

placed. This allowed the outermost row or oarsmen enough

leverage

to complete their strokes without

lowering the efficiency.[82]

Roman era

Galleys from 4th century BC up to the time of the early

Roman Empire

in the 1st century AD became

successively larger and heavier. Three levels of oars had proved to be the

practical limit, but it was improved on by making ships longer, broader and

heavier and placing more than one rower per oar. Naval conflict grew more

intense and extensive, and by 100 BC galleys with four, five or six rows of

oarsmen were commonplace and carried large complements of soldiers and

catapults. With high freeboards (up to 3 m) and additional tower structures from

which missiles could be shot down onto enemy decks, they were intended to be

like floating fortresses.[83]

Designs with everything from eight rows of oarsmen and upwards were built, but

most of them are believed to have been impractical show pieces never used in

actual warfare.[84]

Ptolemy IV

, the Greek pharaoh of Egypt 221-205

BC is recorded as building a gigantic ship with forty rows of oarsmen, but

without specification of its design. A suggested construction was that of a huge

trireme catamaran

with up to 14 men per oar.[85]

The size of ancient galleys, and fleets, reached their peak in ancient times

with the defeat of

Mark Antony

by

Octavian

at the

battle of Actium

. Well-organized contenders for

the power over the Mediterranean did not appear again until several centuries

later, during the

Roman civil wars of the 4th century

, and the

size of galleys decreased considerably. The huge polyremes disappeared and were

replaced by triremes and

liburnian

s, compact biremes with 25 pairs

of oars that were well suited for patrol duty and chasing down pirates.[86]

In the northern provinces oared patrol boats were employed to keep local tribes

in check along the shores of rivers like the

Rhine

and the

Danube

.[87]

As the need for large warships disappeared, the design of the

trireme

, the pinnacle of ancient war ship

design, was forgotten. The last known reference to triremes in battle is dated

to 324 at the

battle of the Hellespont

. In the late 5th

century the Byzantine historian

Zosimus

declared the knowledge of how to build

them to have been long since forgotten.[88]

Middle Ages

Typical specifications

The earliest galley specification comes from an order of

Charles I of Sicily

, in 1275 AD.[89]

Overall length 39.30 m, keel

length 28.03 m, depth 2.08 m. Hull width

3.67 m. Width between

outriggers

4.45 m. 108 oars, most 6.81 m long,

some 7.86 m, 2 steering oars 6.03 m long. Foremast and middle mast respectively

heights 16.08 m, 11.00 m; circumference both 0.79 m, yard lengths 26.72 m, 17.29

m. Overall

deadweight

tonnage approximately 80 metric

tons. This type of vessel had two, later three, men on a

bench

, each working his own oar. This vessel

had much longer oars than the Athenian trireme which were 4.41 m & 4.66 m long.[90]

This type of warship was called galia sottil.[91]

According to Landström, the Medieval galleys had no rams as

boarding

was considered more important method

of warfare than ramming.

Medieval galleys like this pioneered the use of

naval guns

, pointing forward as a supplement to

the above-waterline

beak designed to break the enemies outrigger. Only in the 16th century were

ships called galleys developed with many men to each oar.[92]

Byzantine navy

The primary warship of the Byzantine navy until the 12th century was the

dromon

and other similar ship types. Considered

an evolution of the Roman

liburnian

, the term first appeared in the late

5th century, and was commonly used for a specific kind of war-galley by the 6th

century.[93]

The term drom�n (literally “runner”) itself comes from the Greek root

drom-(á�), “to run”, and 6th-century authors like

Procopius

are explicit in their references to

the speed of these vessels.[94]

During the next few centuries, as the naval struggle with the Arabs intensified,

heavier versions with two or possibly even three banks of oars evolved.[95]

The accepted view is that the main developments which differentiated the

early dromons from the liburnians, and that henceforth characterized

Mediterranean galleys, were the adoption of a full

deck

, the abandonment of

rams

on the bow in favor of an above-water

spur, and the gradual introduction of

lateen

sails.[96]

The exact reasons for the abandonment of the ram are unclear. Depictions of

upward-pointing beaks in the 4th-century

Vatican Vergil

manuscript may well

illustrate that the ram had already been replaced by a spur in late Roman

galleys.[97]

One possibility is that the change occurred because of the gradual evolution of

the ancient shell-first construction method, against which rams had been

designed, into the skeleton-first method, which produced a stronger and more

flexible hull, less susceptible to ram attacks.[98]

At least by the early 7th century, the ram’s original function had been

forgotten.[99]

Belisarius’ invasion fleet of 533 was at least partly fitted with lateen sails,

making it probable that by the time the lateen had become the standard rig for

the dromon,[100]

with the traditional square sail gradually falling from use in medieval

navigation in the Mediterranean.[101]

The dromons that Procopius described were single-banked ships of probably 25

oars per side. Unlike ancient vessels, which used an

outrigger

, these extended directly from the

hull.[102]

In the later bireme

dromons of the 9th and 10th centuries,

the two oar banks were divided by the deck, with the first oar bank was situated

below, whilst the second oar bank was situated above deck; these rowers were

expected to fight alongside the marines in boarding operations.[103]

The overall length of these ships was probably about 32 meters.[104]

The stern

(prymnē), which also housed a tent

that covered the captain’s berth.[105]

The prow featured an elevated forecastle (pseudopation), below which one

or more siphons for the discharge of

Greek fire

projected.[106]

A pavesade on which marines could hang their shields ran around the sides of the

ship, providing protection to the deck crew.[107]

Larger ships also had wooden castles on either side between the masts, providing

archers with elevated firing platforms.[108]

The bow spur was intended to ride over an enemy ship’s oars, breaking them and

rendering it helpless against missile fire and boarding actions.[109]

Early modern

The ubiquitous bow fighting platform (rambade) of early

modern galleys. This model is of a 1715 Swedish galley, somewhat

smaller than the standard Mediterranean war galley, but still based

on the same design.

With the introduction of guns in the bows of galleys, a permanent wooden

structure called rambade (French: rambade; Italian: rambata;

Spanish: arrumbada) was introduced. The rambade became standard on

virtually all galleys in the early 16th century. There were some variations in

the navies of different Mediterranean powers, but the overall layout was the

same. The forward-aiming battery was covered by a wooden platform which gave

gunners a minimum of protection, and functioned as both a staging area for

boarding attacks and as a firing platform for on-board soldiers.[110]

At the

Battle of Lepanto

in 1571, the standard

Venetian war galleys were 42 m long and 5.1 m wide (6.7 m with the rowing

frame), had a

draught

of 1.7 m and a

freeboard

of 1.0 m, and weighed empty about 140

tons. The larger flagship galleys (lanterna, “lantern”) were 46 m long

and 5.5 m wide (7.3 m with the rowing frame), had 1.8 m draught and 1.1 m

freeboard. and weighed 180 tons. The standard galleys had 24 rowing benches on

each side, with three rowers to a bench. (One bench on each side was typically

removed to make space for platforms carrying the

skiff

and the

stove

.) The crew typically comprised 10

officers

, about 65

sailors

, gunners and other staff plus 138

rowers. The “lanterns” had 27 benches on each side, with 156 rowers, and a crew

of 15 officers and about 105 other sailors, gunners and soldiers. The regular

galleys carried one 50-pound

cannon

or a 32-pound

culverin

at the bow as well as four lighter

cannons and four swivel guns. The larger lanterns carried one heavy gun plus six

12 and 6 pound culverins and eight swivel guns.

In the mid-17th century, galleys reached what has been described as their

“final form”.[111]

Galleys had looked more or less the same for over four centuries and a fairly

standardized classification system for different sizes of galleys had been

developed by the Mediterranean bureaucracies, based mostly on the number of

benches in a vessel.[112]

With the exception of a few significantly larger “flagships” (often called

“lantern galleys”), a Mediterranean galley would have 25-26 pairs of oars with

five men per oar (c. 250 rowers). The armament consisted of one heavy 24- or

36-pounder gun in the bows flanked by two to four 4- to 12-pounders. Rows of

light swivel guns

were often placed along the entire

length of the galley on the railings for close-quarter defense. The

length-to-width ratio of the ships was about 8:1, with two main masts carrying

one large lateen

sail each. One was placed in the bows,

stepped slightly to the side to allow for the recoil of the heavy guns; the

other was placed roughly in the center of the ship. A third smaller mast, a “mizzen”

further astern, could be raised if the need and circumstances called for it.[111]

In the Baltic, galleys were generally shorter with a length-to-width ratio from

5:1 to 7:1, an adaptation to the cramped conditions of the Baltic archipelagos.

The documentary evidence for the construction of ancient galleys is

fragmentary, particularly in pre-Roman times. Plans and schematics in the modern

sense did not exist until the 17th century and nothing like them has survived

from ancient times. How galleys were constructed has therefore been a matter of

looking at circumstantial evidence in literature, art, coinage and monuments

that include ships, some of them actually in natural size. Since the war galleys

floated even with a ruptured hull and virtually never had any ballast or heavy

cargo that could sink them, not a single wreckage of one has so far been found.

The only exception has been a partial wreckage of a small auxiliary galley from

the Roman era.[115]

The first dedicated war galleys fitted with rams were built with a

mortise and tenon

technique (see illustration),

a so-called shell-first method. In this, the planking of the hull was

strong enough to hold the ship together structurally, and was also watertight.[116]

The ram, the primary weapon of Ancient galleys from around the 8th to the 4th

century, was fitted onto a structure that was attached to hull rather than

directly on the hull. This way galleys would not be holed if the ram was twisted

off in action. It consisted of a massive projecting timber with a thick bronze

casting with horizontal blades that could weigh from 400 kg up to 2 tonnes.[81]

Propulsion

Throughout their long history, galleys relied on rowing as the most important

means of propulsion. The arrangement of rowers during the 1st millennium BC

developed gradually from a single row up to three rows arranged in a complex,

staggered seating arrangement. Anything above three levels, however, proved to

be physically impracticable. Initially, there was only one rower per oar, but

the number steadily increased, with a number of different combinations of rowers

per oar and rows of oars. The ancient terms for galleys was based on the numbers

of rows or rowers plying the oars, not the number of rows of oars. Today it is

best known by a modernized Latin terminology based on numerals with the ending

“-reme” from rÄ“mus, “oar”. A

trireme

was a ship with three rows of

oarsmen, a quadrireme five, a hexareme six, and so forth. There

were warships that ran up to ten or even eleven rows, but anything above six was

rare. A huge forty-rowed ship was built during the reign of

Ptolemy IV

in Egypt. Little is known about its

design, but it is assumed to have been an impractical prestige vessel.

Ancient rowing was done in a fixed seated position, the most effective rowing

position, with rowers facing the stern. A sliding stroke, which provided the

strength from both legs as well as the arms, was suggested by earlier

historians, but no conclusive evidence has supported it. Practical experiments

with the full-scale reconstruction Olympias has shown that there was

insufficient space, while moving or rolling seats would have been highly

impractical to construct with ancient methods.[117]

Rowers in ancient war galleys sat below the upper deck with little view of their

surroundings. The rowing was therefore managed by supervisors, and coordinated

with pipes or rhythmic chanting.[118]

Galleys were highly maneuverable, able to turn on their axis or even to row

backwards, though it required a skilled and experienced crew.[119]

In galleys with an arrangement of three men per oar, all would be seated, but

the rower furthest inboard would perform a stand-and-sit stroke, getting up on

his feet to push the oar forwards and then sitting down again to pull it back.[119]

The faster a vessel travels, the more energy it uses. Reaching high speed

requires energy which a human-powered vessel is incapable of producing. Oar

system generate very low amounts of energy for propulsion (only about 70 W per

rower) and the upper limit for rowing in a fixed position is around 10 knots.[120]

Ancient war galleys of the kind used in Classical Greece are by modern

historians considered to be the most energy efficient and fastest of galley

designs throughout history. A full-scale replica of a 5th century BC

trireme

, the

Olympias

was built 1985-87 and was put to a

series trials to test its performance. It proved that a cruising speed of 7-8

knots could be maintained for an entire day. Sprinting speeds of up to 10 knots

were possible, but only for a few minutes and would tire the crew quickly.[121]

Ancient galleys were built very light and the original triremes are assumed to

never have been surpassed in speed.[122]

Medieval galleys are believed to have been considerably slower, especially since

they were not built with ramming tactics in mind. A cruising speed of no more

than 2-3 knots has been estimated. A sprint speed of up to 7 knots was possible

for 20–30 minutes, but risked exhausting the rowers completely.[123]

Rowing in headwinds or even moderately rough weather was difficult as well as

exhausting.[124]

In high seas, ancient galleys would set sail to run before the wind. They were

highly susceptible to high waves, and could become unmanageable if the rowing

frame (apostis) came awash. Ancient and medieval galleys are assumed to

sailed only with the wind more or less astern with a top speed of 8-9 knots in

fair conditions.[125]

In ancient galleys, most of the moving power came from a singe

square sail

on a mast rigged a little forwards

of the center of the ship with a smaller mast carrying a

head sail

in the bow. Triangular

lateen

sails are attested as early as the 2nd

century AD, and gradually became the sail of choice for galleys. By the 9th

century lateens firmly established as part of the standard galley rig. It was

more complicated and required a larger crew to handle than a square sail rig,

but this was not a problem in the heavily-manned galleys.[126]

Unlike a square sail rig, the

spar

of a lateen sail does not pivot around the

mast. To change

tacks

, the entire spar, often much longer than

the mast itself, had to be lifted over the mast and to the other side, a complex

and time-consuming maneuver.[127]

Strategy and tactics

In the earliest times of naval warfare

boarding

was the only means of deciding a naval

engagement, but little to nothing is known about the tactics involved. In the

first recorded naval battle in history, the

battle of the Delta

, the forces of Egyptian

Pharaoh Ramesses III

won a decisive victory over a

force made up of the enigmatic group known as the

Sea Peoples

. As shown in commemorative reliefs

of the battle, Egyptian archers on ships and the nearby shores of the Nile rain

down arrows on the enemy ships. At the same time Egyptian galleys engage in

boarding action and

capsize

the ships of the Sea Peoples with ropes

attached to grappling hooks thrown into the rigging.[128]

Around the 8th century BC,

ramming

began to be employed as war galleys

were equipped with heavy bronze rams. Records of the

Persian Wars

in the early 5th century BC by the

Ancient historian

Herodotus

(c. 484-25 BC) show that by this time

ramming tactics had evolved among the Greeks. The formations could either be in

columns in line ahead, one ship following the next, or in a line abreast, with

the ships side by side, depending on the tactical situation and the surrounding

geography. There were two primary methods for attack: by breaking through the

enemy formation (diekplous) or by outflanking it (periplous). The

diekplous involved a concentrated charge in line ahead so as to break a

hole in the enemy line, allowing galleys to break through and then wheel to

attack the enemy line from behind. The periplous involved outflanking or

encircling the enemy so as to attack them in the vulnerable rear or side by line

abreast.[129]

If one side knew that it had slower ships, a common tactic was to form a circle

with the bows pointing outwards, thereby avoiding being outflanked. At a given

signal, the circle could then fan out in all directions, trying to pick off

individual enemy ships. To counter this formation, the attacking side would

rapidly circle, feigning attacks in order to find gaps in the formation to

exploit.[130]

Ramming itself was done by smashing into the rear or side of an enemy ship,

punching a hole in the planking. This did not actually sink an ancient galley

unless it was heavily laden with cargo and stores. With a normal load, it was

buoyant enough to float even with a breached hull. It could also maneuver for

some time as long as the oarsmen were not incapacitated, but would gradually