|

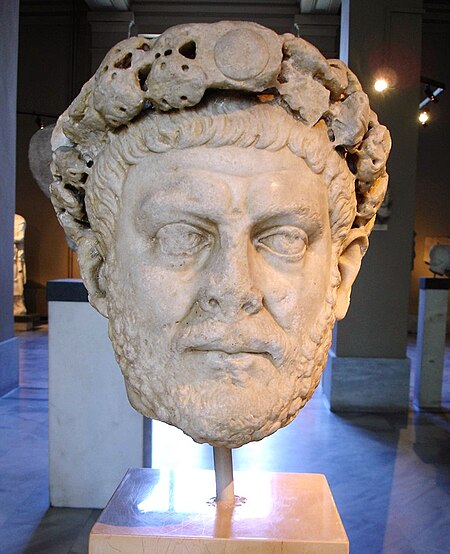

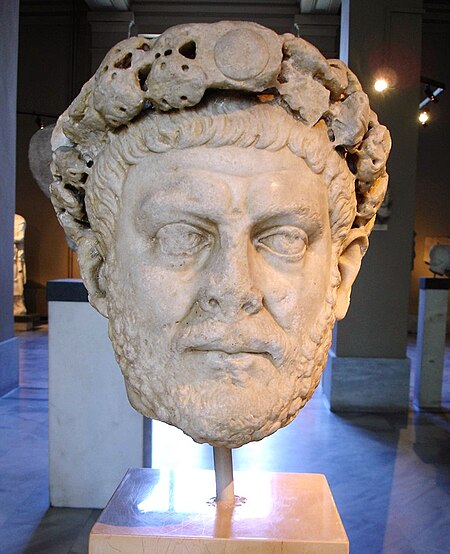

Diocletian

–

Roman Emperor

: 284-305 A.D.

Potin Tetradrachm 20mm (9.02 grams) of

Alexandria

in

Egypt

Struck Regnal Year 7, 290/291 A.D.

Reference: Dattari 5776; Geissen 3250

ΔIOKΛHTIANOC CЄB, Laureate head right.

Nude Zeus standing left, holding patera and scepter; eagle at his feet to left;

L Z (date) across fields.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

In the

ancient Greek

religion, Zeus was the

“Father of Gods and men” (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν

τε)

who ruled the Olympians of

Mount Olympus

as a father ruled the family. He was the

god of sky

and

thunder

in

Greek mythology

.

His

Roman

counterpart is

Jupiter

and

Etruscan

counterpart is Tinia

.![The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c8/Jupiter_Smyrna_Louvre_Ma13.jpg/200px-Jupiter_Smyrna_Louvre_Ma13.jpg)

Zeus was the child of

Cronus

and

Rhea

,

and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he was married to

Hera, although, at the

oracle of Dodona

,

his consort was

Dione

:

according to the Iliad

,

he is the father of

Aphrodite

by Dione. He is known for his erotic escapades. These resulted in many godly and

heroic offspring, including

Athena

,

Apollo

and Artemis

,

Hermes

,

Persephone

(by Demeter

),

Dionysus

,

Perseus

,

Heracles

,

Helen of Troy

,

Minos

,

and the Muses

(by Mnemosyne

);

by Hera, he is usually said to have fathered

Ares,

Hebe

and Hephaestus

.

As

Walter Burkert

points out in his book, Greek Religion, “Even the gods who are not his

natural children address him as Father, and all the gods rise in his presence.”

For the Greeks, he was the

King of the Gods

,

who oversaw the universe. As

Pausanias

observed, “That Zeus is king in heaven is a saying common to all men”. In

Hesiod’s Theogony

Zeus assigns the various gods their roles. In the Homeric Hymns he is

referred to as the chieftain of the gods.

His symbols are the

thunderbolt

,

eagle

,

bull

,

and oak

.

In addition to his Indo-European inheritance, the classical “cloud-gatherer”

also derives certain iconographic traits from the cultures of the

Ancient Near East

,

such as the

scepter

.

Zeus is frequently depicted by Greek artists in one of two poses: standing,

striding forward, with a thunderbolt leveled in his raised right hand, or seated

in majesty.

Alexandria was founded

by

Alexander the Great

in April 331 BC as

Ἀλεξάνδρεια (Alexándreia).

Alexander’s

chief architect

for the project was

Dinocrates

. Alexandria was intended to

supersede Naucratis

as a

Hellenistic

center in Egypt, and to be the link

between Greece and the rich

Nile Valley. An Egyptian city,

Rhakotis

, already existed on the shore, and

later gave its name to Alexandria in the

Egyptian language

(Egyptian *Raˁ-Ḳāṭit,

written rˁ-ḳṭy.t, ‘That which is built up’). It continued to exist as the

Egyptian quarter of the city. A few months after the foundation, Alexander left

Egypt and never returned to his city. After Alexander’s departure, his viceroy,

Cleomenes

, continued the expansion. Following a

struggle with the other successors of Alexander, his general

Ptolemy

succeeded in bringing Alexander’s body

to Alexandria.

Alexandria, sphinx made of

pink granite

,

Ptolemaic

.

Although Cleomenes was mainly in charge of overseeing Alexandria’s continuous

development, the Heptastadion and the mainland quarters seem to have been

primarily Ptolemaic work. Inheriting the trade of ruined

Tyre

and becoming the centre of the new

commerce between Europe and the

Arabian

and Indian East, the city grew in less

than a generation to be larger than

Carthage

. In a century, Alexandria had become

the largest city in the world and, for some centuries more, was second only to

Rome. It became Egypt’s main Greek city, with

Greek people

from diverse backgrounds.

Alexandria was not only a centre of

Hellenism

, but was also home to the largest

Jewish community in the world. The

Septuagint

, a Greek translation of the

Hebrew Bible

, was produced there. The early

Ptolemies kept it in order and fostered the development of its museum into the

leading Hellenistic center of learning (Library

of Alexandria), but were careful to maintain the distinction of its

population’s three largest ethnicities: Greek, Jewish, and

Egyptian

. From this division arose much of the

later turbulence, which began to manifest itself under

Ptolemy Philopater

who reigned from 221–204 BC.

The reign of

Ptolemy VIII Physcon

from 144–116 BC was marked

by purges and civil warfare.

The city passed formally under Roman jurisdiction in 80 BC, according to the

will of

Ptolemy Alexander

, but only after it had been

under Roman influence for more than a hundred years. It was captured by

Julius Caesar

in 47 BC during a Roman

intervention in the domestic civil war between king

Ptolemy XIII

and his advisers, and the fabled

queen

Cleopatra VII

. It was finally captured by

Octavian

, future

emperor

Augustus on 1 August 30 BC, with the

name of the month later being changed to August to commemorate his

victory.

In AD 115, large parts of Alexandria were destroyed during the

Kitos War

, which gave

Hadrian

and his architect,

Decriannus

, an opportunity to rebuild it. In

215, the

emperor

Caracalla

visited the city and, because of some

insulting satires

that the inhabitants had directed at

him, abruptly commanded his troops to

put to death

all youths capable of bearing

arms. On 21 July 365, Alexandria was devastated by a

tsunami

(365

Crete earthquake), an event still annually commemorated 17 hundred

years later as a “day of horror.” In the late 4th century, persecution of

pagans

by newly Christian Romans had reached

new levels of intensity. In 391, the Patriarch

Theophilus

destroyed all pagan temples in

Alexandria under orders from Emperor

Theodosius I

. The

Brucheum

and Jewish quarters were desolate in

the 5th century. On the mainland, life seemed to have centred in the vicinity of

the Serapeum and

Caesareum

, both of which became

Christian churches

. The

Pharos

and Heptastadium quarters,

however, remained populous and were left intact.

In 619, Alexandria

fell

to the

Sassanid Persians

. Although the

Byzantine Emperor

Heraclius

recovered it in 629, in 641 the Arabs

under the general

Amr ibn al-As

captured it during the

Muslim conquest of Egypt

, after a siege that

lasted 14 months.

Diocletian (Latin:

Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus Augustus;

c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a

Roman Emperor

from 284 to 305. Born to a family

of low status in the

Roman province of Dalmatia

, Diocletian rose

through the ranks of the military to become cavalry commander to the Emperor

Carus

. After the deaths of Carus and his son

Numerian

on campaign in Persia, Diocletian was

proclaimed Emperor. The title was also claimed by Carus’ other surviving son,

Carinus

, but Diocletian defeated him in the

Battle of the Margus

. Diocletian’s reign

stabilized the Empire and marks the end of the

Crisis of the Third Century

. He appointed

fellow officer Maximian

Augustus

his senior co-emperor in 285.

Diocletian delegated further on 1 March 293, appointing

Galerius

and

Constantius

as

Caesars

, junior co-emperors. Under this “Tetrarchy“,

or “rule of four”, each emperor would rule over a quarter-division of the

Empire. Diocletian secured the Empire’s borders and purged it of all threats to

his power. He defeated the

Sarmatians

and

Carpi

during several campaigns between 285 and

299, the

Alamanni

in 288, and usurpers in

Egypt

between 297 and 298. Galerius, aided by

Diocletian, campaigned successfully against

Sassanid Persia

, the Empire’s traditional

enemy. In 299 he sacked their capital,

Ctesiphon

. Diocletian led the subsequent

negotiations and achieved a lasting and favorable peace. Diocletian separated

and enlarged the Empire’s civil and military services and reorganized the

Empire’s provincial divisions, establishing the largest and most

bureaucratic

government in the history of the

Empire. He established new administrative centers in

Nicomedia

,

Mediolanum

,

Antioch

, and

Trier

, closer to the Empire’s frontiers than

the traditional capital at Rome had been. Building on third-century trends

towards absolutism

, he styled himself an autocrat,

elevating himself above the Empire’s masses with imposing forms of court

ceremonies and architecture. Bureaucratic and military growth, constant

campaigning, and construction projects increased the state’s expenditures and

necessitated a comprehensive tax reform. From at least 297 on, imperial taxation

was standardized, made more equitable, and levied at generally higher rates.

Not all of Diocletian’s plans were successful: the

Edict on Maximum Prices

(301), his attempt

to curb inflation

via

price controls

, was counterproductive and

quickly ignored. Although effective while he ruled, Diocletian’s Tetrarchic

system collapsed after his abdication under the competing dynastic claims of

Maxentius

and

Constantine

, sons of Maximian and Constantius

respectively. The

Diocletianic Persecution

(303–11), the Empire’s

last, largest, and bloodiest official persecution of

Christianity

, did not destroy the Empire’s

Christian community; indeed, after 324 Christianity became the empire’s

preferred religion under its first Christian emperor,

Constantine

.

In spite of his failures, Diocletian’s reforms fundamentally changed the

structure of Roman imperial government and helped stabilize the Empire

economically and militarily, enabling the Empire to remain essentially intact

for another hundred years despite being near the brink of collapse in

Diocletian’s youth. Weakened by illness, Diocletian left the imperial office on

1 May 305, and became the only Roman emperor to voluntarily abdicate the

position. He lived out his retirement in

his palace

on the Dalmatian coast, tending to

his vegetable gardens. His palace eventually became the core of the modern-day

city of

Split

.

Early life

Diocletian was probably born near

Salona

in

Dalmatia

(Solin

in modern Croatia

), some time around 244. His parents

named him Diocles, or possibly Diocles Valerius. The modern historian

Timothy Barnes

takes his official birthday, 22

December, as his actual birthdate. Other historians are not so certain. Diocles’

parents were of low status, and writers critical of him claimed that his father

was a scribe

or a

freedman

of the senator Anullinus, or even that

Diocles was a freedman himself. The first forty years of his life are mostly

obscure. The

Byzantine

chronicler

Joannes Zonaras

states that he was

Dux

Moesiae

, a commander of forces on the lower

Danube

. The often-unreliable

Historia Augusta

states that he served in

Gaul, but this account is not corroborated by other sources and is ignored by

modern historians of the period.

Death of Numerian

Emperor Carus

‘ death left his unpopular sons Numerian

and Carinus as the new Augusti. Carinus quickly made his way to Rome from

Gaul and arrived by January 284. Numerian lingered in the east. The Roman

withdrawal from Persia was orderly and unopposed. The

Sassanid

king

Bahram II

could not field an army against them

as he was still struggling to establish his authority. By March 284, Numerian

had only reached Emesa (Homs)

in

Syria

; by November, only Asia Minor. In Emesa

he was apparently still alive and in good health: he issued the only extant

rescript

in his name there, but after he left

the city, his staff, including the prefect

Aper

, reported that he suffered from an

inflammation of the eyes. He traveled in a closed coach from then on. When the

army reached Bithynia

, some of the soldiers smelled an odor

emanating from the coach. They opened its curtains and inside they found

Numerian dead.

Aper officially broke the news in

Nicomedia

(İzmit)

in November. Numerianus’ generals and tribunes called a council for the

succession, and chose Diocles as Emperor, in spite of Aper’s attempts to garner

support. On 20 November 284, the army of the east gathered on a hill 5

kilometres (3.1 mi) outside Nicomedia. The army unanimously saluted Diocles as

their new Augustus, and he accepted the purple imperial vestments. He raised his

sword to the light of the sun and swore an oath disclaiming responsibility for

Numerian’s death. He asserted that Aper had killed Numerian and concealed it. In

full view of the army, Diocles drew his sword and killed Aper. According to the

Historia Augusta, he quoted from

Virgil

while doing so. Soon after Aper’s death,

Diocles changed his name to the more Latinate “Diocletianus”, in full Gaius

Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus.

Conflict with Carinus

After his accession, Diocletian and Lucius Caesonius Bassus were named as

consuls and assumed the

fasces

in place of Carinus and Numerianus.

Bassus was a member of a

senatorial

family from

Campania

, a former consul and proconsul of

Africa, chosen by Probus for signal distinction. He was skilled in areas of

government where Diocletian presumably had no experience. Diocletian’s elevation

of Bassus as consul symbolized his rejection of Carinus’ government in Rome, his

refusal to accept second-tier status to any other emperor, and his willingness

to continue the long-standing collaboration between the Empire’s senatorial and

military aristocracies. It also tied his success to that of the Senate, whose

support he would need in his advance on Rome.

Diocletian was not the only challenger to Carinus’ rule: the usurper

M. Aurelius Julianus

, Carinus’ corrector

Venetiae, took control of northern

Italy

and

Pannonia

after Diocletian’s accession. Julianus

minted coins from the mint at Siscia (Sisak,

Croatia) declaring himself as Emperor and promising freedom. It was all good

publicity for Diocletian, and it aided in his portrayal of Carinus as a cruel

and oppressive tyrant. Julianus’ forces were weak, however, and were handily

dispersed when Carinus’ armies moved from Britain to northern Italy. As leader

of the united East, Diocletian was clearly the greater threat. Over the winter

of 284–85, Diocletian advanced west across the

Balkans

. In the spring, some time before the

end of May, his armies met Carinus’ across the river Margus (Great

Morava) in

Moesia

. In modern accounts, the site has been

located between the Mons Aureus (Seone, west of

Smederevo

) and

Viminacium

, near modern

Belgrade

, Serbia.

Despite having the stronger army, Carinus held the weaker position. His rule

was unpopular, and it was later alleged that he had mistreated the Senate and

seduced his officers’ wives. It is possible that

Flavius Constantius

, the governor of Dalmatia

and Diocletian’s associate in the household guard, had already defected to

Diocletian in the early spring. When the

Battle of the Margus

began, Carinus’ prefect

Aristobulus also defected. In the course of the battle, Carinus was killed by

his own men. Following Diocletian’s victory, both the western and the eastern

armies acclaimed him Augustus. Diocletian exacted an oath of allegiance from the

defeated army and departed for Italy.

Early rule

Diocletian may have become involved in battles against the

Quadi

and

Marcomanni

immediately after the Battle of the

Margus. He eventually made his way to northern Italy and made an imperial

government, but it is not known whether he visited the city of Rome at this

time. There is a contemporary issue of coins suggestive of an imperial

adventus

(arrival) for the city, but some

modern historians state that Diocletian avoided the city, and that he did so on

principle, as the city and its Senate were no longer politically relevant to the

affairs of the Empire and needed to be taught as much. Diocletian dated his

reign from his elevation by the army, not the date of his ratification by the

Senate, following the practice established by Carus, who had declared the

Senate’s ratification a useless formality. If Diocletian ever did enter Rome

shortly after his accession, he did not stay long; he is attested back in the

Balkans by 2 November 285, on campaign against the

Sarmatians

.

Diocletian replaced the

prefect

of Rome with his consular colleague

Bassus. Most officials who had served under Carinus, however, retained their

offices under Diocletian. In an act of clementia denoted by the

epitomator

Aurelius Victor

as unusual, Diocletian did not

kill or depose Carinus’ traitorous praetorian prefect and consul Ti. Claudius

Aurelius Aristobulus, but confirmed him in both roles. He later gave him the

proconsulate of Africa and the rank of urban prefect. The other figures who

retained their offices might have also betrayed Carinus.

Maximian made

co-emperor

Maximian’s consistent loyalty to Diocletian proved an important

component of the Tetrarchy’s early successes.

The assassinations of

Aurelian

and Probus demonstrated that sole

rulership was dangerous to the stability of the Empire. Conflict boiled in every

province, from Gaul to Syria, Egypt to the lower Danube. It was too much for one

person to control, and Diocletian needed a lieutenant. At some time in 285 at

Mediolanum

(Milan),

Diocletian raised his fellow-officer

Maximian

to the office of

Caesar

, making him co-emperor.

The concept of dual rulership was nothing new to the Roman Empire.

Augustus

, the first Emperor, had nominally

shared power with his colleagues, and more formal offices of co-Emperor had

existed from

Marcus Aurelius

on. Most recently, the emperor

Carus and his sons had ruled together, albeit unsuccessfully. Diocletian was in

a less comfortable position than most of his predecessors, as he had a daughter,

Valeria, but no sons. His co-ruler had to be from outside his family, raising

the question of trust. Some historians state that Diocletian adopted Maximian as

his filius Augusti, his “Augustan son”, upon his appointment to the

throne, following the precedent of some previous emperors. This argument has not

been universally accepted.

The relationship between Diocletian and Maximian was quickly couched in

religious terms. Around 287 Diocletian assumed the title Iovius, and

Maximian assumed the title Herculius. The titles were probably meant to

convey certain characteristics of their associated leaders. Diocletian, in

Jovian

style, would take on the dominating

roles of planning and commanding; Maximian, in

Herculian

mode, would act as Jupiter’s

heroic subordinate. For all their religious connotations, the

emperors were not “gods” in the tradition of the

Imperial cult

—although they may have been

hailed as such in Imperial

panegyrics

. Instead, they were seen as the

gods’ representatives, effecting their will on earth. The shift from military

acclamation to divine sanctification took the power to appoint emperors away

from the army. Religious legitimization elevated Diocletian and Maximian above

potential rivals in a way military power and dynastic claims could not.

Conflict

with Sarmatia and Persia

After his acclamation, Maximian was dispatched to fight the rebel

Bagaudae

in Gaul. Diocletian returned to the

East, progressing slowly. By 2 November, he had only reached Citivas Iovia

(Botivo, near Ptuj

,

Slovenia

). In the Balkans during the autumn of

285, he encountered a tribe of

Sarmatians

who demanded assistance. The

Sarmatians requested that Diocletian either help them recover their lost lands

or grant them pasturage rights within the Empire. Diocletian refused and fought

a battle with them, but was unable to secure a complete victory. The nomadic

pressures of the

European Plain

remained and could not be solved

by a single war; soon the Sarmatians would have to be fought again.

Diocletian wintered in

Nicomedia

. There may have been a revolt in the

eastern provinces at this time, as he brought settlers from

Asia

to populate emptied farmlands in

Thrace

. He visited

Syria Palaestina

the following spring, His stay

in the East saw diplomatic success in the conflict with Persia: in 287,

Bahram II

granted him precious gifts, declared

open friendship with the Empire, and invited Diocletian to visit him. Roman

sources insist that the act was entirely voluntary.

Around the same time, perhaps in 287, Persia relinquished claims on

Armenia

and recognized Roman authority over

territory to the west and south of the Tigris. The western portion of Armenia

was incorporated into the Empire and made a province.

Tiridates III

,

Arsacid

claimant to the Armenian throne and

Roman client, had been disinherited and forced to take refuge in the Empire

after the Persian conquest of 252-53. In 287, he returned to lay claim to the

eastern half of his ancestral domain and encountered no opposition. Bahram II’s

gifts were widely recognized as symbolic of a victory in the ongoing

conflict with Persia

, and Diocletian was hailed

as the “founder of eternal peace”. The events might have represented a formal

end to Carus’ eastern campaign, which probably ended without an acknowledged

peace. At the conclusion of discussions with the Persians, Diocletian

re-organized the Mesopotamian frontier and fortified the city of

Circesium

(Buseire, Syria) on the

Euphrates

.

Maximian made

Augustus

Maximian’s campaigns were not proceeding as smoothly. The Bagaudae had been

easily suppressed, but

Carausius

, the man he had put in charge of

operations against Saxon

and

Frankish

pirates

on the

Saxon Shore

, had begun keeping the goods seized

from the pirates for himself. Maximian issued a death-warrant for his larcenous

subordinate. Carausius fled the Continent, proclaimed himself Augustus, and

agitated Britain and northwestern Gaul into open revolt against Maximian and

Diocletian. Spurred by the crisis, on 1 April 286, Maximian took up the title of

Augustus

. His appointment is unusual in that it

was impossible for Diocletian to have been present to witness the event. It has

even been suggested that Maximian usurped the title and was only later

recognized by Diocletian in hopes of avoiding civil war. This suggestion is

unpopular, as it is clear that Diocletian meant for Maximian to act with a

certain amount of independence.

Maximian realized that he could not immediately suppress the rogue commander,

so in 287 he campaigned solely against tribes beyond the

Rhine

instead. The following spring, as

Maximian prepared a fleet for an expedition against Carausius, Diocletian

returned from the East to meet Maximian. The two emperors agreed on a joint

campaign against the

Alamanni

. Diocletian invaded Germania through

Raetia while Maximian progressed from Mainz. Each emperor burned crops and food

supplies as he went, destroying the Germans’ means of sustenance. The two men

added territory to the Empire and allowed Maximian to continue preparations

against Carausius without further disturbance. On his return to the East,

Diocletian managed what was probably another rapid campaign against the

resurgent Sarmatians. No details survive, but surviving inscriptions indicate

that Diocletian took the title Sarmaticus Maximus after 289.

In the East, Diocletian engaged in diplomacy with desert tribes in the

regions between Rome and Persia. He might have been attempting to persuade them

to ally themselves with Rome, thus reviving the old, Rome-friendly,

Palmyrene

sphere of influence

, or simply attempting to

reduce the frequency of their incursions. No details survive for these events.

Some of the princes of these states were Persian client kings, a disturbing fact

in light of increasing tensions with the Sassanids. In the West, Maximian lost

the fleet built in 288 and 289, probably in the early spring of 290. The

panegyrist

who refers to the loss suggests that

its cause was a storm, but this might simply be the an attempt to conceal an

embarrassing military defeat. Diocletian broke off his tour of the Eastern

provinces soon thereafter. He returned with haste to the West, reaching Emesa by

10 May 290, and Sirmium on the Danube by 1 July 290.

Diocletian met Maximian in Milan in the winter of 290–91, either in late

December 290 or January 291. The meeting was undertaken with a sense of solemn

pageantry. The Emperors spent most of their time in public appearances. It has

been surmised that the ceremonies were arranged to demonstrate Diocletian’s

continuing support for his faltering colleague. A deputation from the Roman

Senate met with the Emperors, renewing its infrequent contact with the Imperial

office. The choice of Milan over Rome further snubbed the capital’s pride. But

then it was already a long established practice that Rome itself was only a

ceremonial capital, as the actual seat of the Imperial administration was

determined by the needs of defense. Long before Diocletian,

Gallienus

(r. 253–68) had chosen Milan as the

seat of his headquarters. If the panegyric detailing the ceremony implied that

the true center of the Empire was not Rome, but where the Emperor sat (“…the

capital of the Empire appeared to be there, where the two emperors met”), it

simply echoed what had already been stated by the historian

Herodian

in the early third century: “Rome is

where the emperor is”. During the meeting, decisions on matters of politics and

war were probably made in secret. The Augusti would not meet again until 303.

Tetrarchy

Foundation of the

Tetrarchy

Triumphal Arch of the Tetrarchy,

Sbeitla

,

Tunisia

Some time after his return, and before 293, Diocletian transferred command of

the war against Carausius from Maximian to

Constantius Chlorus

, a former governor of

Dalmatia and a man of military experience stretching back to

Aurelian

‘s campaigns against

Zenobia

(272–73). He was Maximian’s praetorian

prefect in Gaul, and the husband to Maximian’s daughter,

Theodora

. On 1 March 293 at Milan, Maximian

gave Constantius the office of Caesar. In the spring of 293, in either

Philippopolis (Plovdiv,

Bulgaria

) or Sirmium, Diocletian would do the

same for Galerius

, husband to Diocletian’s daughter

Valeria, and perhaps Diocletian’s praetorian prefect. Constantius was assigned

Gaul and Britain. Galerius was assigned Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and

responsibility for the eastern borderlands.

This arrangement is called the Tetrarchy, from a

Greek

term meaning “rulership by four”. The

Tetrarchic Emperors were more or less sovereign in their own lands, and they

travelled with their own imperial courts, administrators, secretaries, and

armies. They were joined by blood and marriage; Diocletian and Maximian now

styled themselves as brothers. The senior co-Emperors formally adopted Galerius

and Constantius as sons in 293. These relationships implied a line of

succession. Galerius and Constantius would become Augusti after the departure of

Diocletian and Maximian. Maximian’s son

Maxentius

and Constantius’ son

Constantine

would then become Caesars. In

preparation for their future roles, Constantine and Maxentius were taken to

Diocletian’s court in Nicomedia.

Conflict in

the Balkans and Egypt

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 traveling with Galerius from Sirmium (Sremska

Mitrovica,

Serbia

) to

Byzantium

(Istanbul,

Turkey

). Diocletian then returned to Sirmium,

where he would remain for the following winter and spring. He campaigned against

the Sarmatians again in 294, probably in the autumn, and won a victory against

them. The Sarmatians’ defeat kept them from the Danube provinces for a long

time. Meanwhile, Diocletian built forts north of the Danube, at

Aquincum

(Budapest,

Hungary

), Bononia (Vidin,

Bulgaria), Ulcisia Vetera, Castra Florentium, Intercisa (Dunaújváros,

Hungary), and Onagrinum (Begeč,

Serbia). The new forts became part of a new defensive line called the Ripa

Sarmatica. In 295 and 296 Diocletian campaigned in the region again, and won

a victory over the Carpi in the summer of 296. Afterwards, during 299 and 302,

as Diocletian was then residing in the East, it was Galerius’ turn to campaign

victoriously on the Danube. By the end of his reign, Diocletian had secured the

entire length of the Danube, provided it with forts, bridgeheads, highways, and

walled towns, and sent fifteen or more legions to patrol the region; an

inscription at

Sexaginta Prista

on the Lower Danube extolled

restored tranquilitas at the region. The defense came at a heavy cost,

but was a significant achievement in an area difficult to defend.

Galerius, meanwhile, was engaged during 291–293 in disputes in

Upper Egypt

, where he suppressed a regional

uprising. He would return to Syria in 295 to fight the revanchist Persian

Empire. Diocletian’s attempts to bring the Egyptian tax system in line with

Imperial standards stirred discontent, and a revolt swept the region after

Galerius’ departure. The usurper

L. Domitius Domitianus

declared himself

Augustus in July or August 297. Much of Egypt, including

Alexandria

, recognized his rule. Diocletian

moved into Egypt to suppress him, first putting down rebels in the

Thebaid

in the autumn of 297, then moving on to

besiege Alexandria. Domitianus died in December 297, by which time Diocletian

had secured control of the Egyptian countryside. Alexandria, whose defense was

organized under Diocletian’s former

corrector

Aurelius Achilleus

, held out until a later

date, probably March 298.

Bureaucratic affairs were completed during Diocletian’s stay: a census took

place, and Alexandria, in punishment for its rebellion, lost the ability to mint

independently. Diocletian’s reforms in the region, combined with those of

Septimus Severus

, brought Egyptian

administrative practices much closer to Roman standards. Diocletian travelled

south along the Nile the following summer, where he visited

Oxyrhynchus

and

Elephantine

. In Nubia, he made peace with the

Nobatae

and

Blemmyes

tribes. Under the terms of the peace

treaty Rome’s borders moved north to

Philae

and the two tribes received an annual

gold stipend. Diocletian left Africa quickly after the treaty, moving from Upper

Egypt in September 298 to Syria in February 299. He met up with Galerius in

Mesopotamia.

War with Persia

Invasion, counterinvasion

In 294, Narseh

, a son of Shapur who had been passed

over for the Sassanid succession, came to power in Persia. Narseh eliminated

Bahram III

, a young man installed in the wake

of Bahram II’s death in 293. In early 294, Narseh sent Diocletian the customary

package of gifts between the empires, and Diocletian responded with an exchange

of ambassadors. Within Persia, however, Narseh was destroying every trace of his

immediate predecessors from public monuments. He sought to identify himself with

the warlike kings

Ardashir

(r. 226–41) and

Shapur I

(r. 241–72), who had sacked Roman

Antioch and skinned the Emperor

Valerian

(r. 253–260) to decorate his war

temple.

Narseh declared war on Rome in 295 or 296. He appears to have first invaded

western Armenia, where he seized the lands delivered to Tiridates in the peace

of 287. Narseh moved south into Roman Mesopotamia in 297, where he inflicted a

severe defeat on Galerius in the region between Carrhae (Harran,

Turkey) and Callinicum (Ar-Raqqah,

Syria) (and thus, the historian

Fergus Millar

notes, probably somewhere on the

Balikh River

). Diocletian may or may not have

been present at the battle, but he quickly divested himself of all

responsibility. In a public ceremony at Antioch, the official version of events

was clear: Galerius was responsible for the defeat; Diocletian was not.

Diocletian publicly humiliated Galerius, forcing him to walk for a mile at the

head of the Imperial caravan, still clad in the purple robes of the Emperor.

Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent

collected from the Empire’s Danubian holdings. Narseh did not advance from

Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an

attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia. It is unclear if Diocletian was

present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria. Narseh

retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius’ force, to Narseh’s disadvantage; the

rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid

cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the

second encounter

, Roman forces seized Narseh’s

camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife. Galerius continued moving down the

Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman

territory along the Euphrates.

Peace negotiations

Narseh sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives

and children in the course of the war, but Galerius had dismissed him. Serious

peace negotiations began in the spring of 299. The magister memoriae

(secretary) of Diocletian and Galerius, Sicorius Probus, was sent to Narseh to

present terms. The conditions of the resulting

Peace of Nisibis

were heavy: Armenia returned

to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border;

Caucasian Iberia

would pay allegiance to Rome

under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole

conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over

the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia: Ingilene, Sophanene (Sophene),

Arzanene (Aghdznik),

Corduene

(Carduene), and Zabdicene (near modern

Hakkâri

, Turkey). These regions included the

passage of the Tigris through the

Anti-Taurus

range; the

Bitlis

pass, the quickest southerly route into

Persian Armenia; and access to the

Tur Abdin

plateau.

A stretch of land containing the later strategic strongholds of Amida (Diyarbakır,

Turkey) and Bezabde came under firm Roman military occupation. With these

territories, Rome would have an advance station north of Ctesiphon, and would be

able to slow any future advance of Persian forces through the region. Many

cities east of the Tigris came under Roman control, including

Tigranokert

,

Saird

,

Martyropolis

,

Balalesa

,

Moxos

,

Daudia

, and Arzan – though under what status is

unclear. At the conclusion of the peace, Tiridates regained both his throne and

the entirety of his ancestral claim. Rome secured a wide zone of cultural

influence, which led to a wide diffusion of

Syriac Christianity

from a center at Nisibis in

later decades, and the eventual Christianization of Armenia.

Religious persecutions

Early persecutions

At the conclusion of the

Peace of Nisibis

, Diocletian and Galerius

returned to Syrian Antioch. At some time in 299, the Emperors took part in a

ceremony of sacrifice

and

divination

in an attempt to predict the future.

The haruspices

were unable to read the entrails of

the sacrificed animals and blamed Christians in the Imperial household. The

Emperors ordered all members of the court to perform a sacrifice to purify the

palace. The Emperors sent letters to the military command, demanding the entire

army perform the required sacrifices or face discharge. Diocletian was

conservative in matters of religion, a man faithful to the traditional Roman

pantheon and understanding of demands for religious purification, but

Eusebius

,

Lactantius

and

Constantine

state that it was Galerius, not

Diocletian, who was the prime supporter of the purge, and its greatest

beneficiary. Galerius, even more devoted and passionate than Diocletian, saw

political advantage in the politics of persecution. He was willing to break with

a government policy of inaction on the issue.

Antioch was Diocletian’s primary residence from 299 to 302, while Galerius

swapped places with his Augustus on the Middle and Lower Danube. He visited

Egypt once, over the winter of 301–2, and issued a grain dole in Alexandria.

Following some public disputes with

Manicheans

, Diocletian ordered that the leading

followers of

Mani

be burnt alive along with their

scriptures. In a 31 March 302 rescript from Alexandria, he declared that

low-status Manicheans must be executed by the blade, and high-status Manicheans

must be sent to work in the quarries of Proconnesus (Marmara

Island, Turkey) or the mines of Phaeno in southern

Palestine

. All Manichean property was to be

seized and deposited in the imperial treasury. Diocletian found much to be

offended by in Manichean religion: its novelty, its alien origins, the way it

corrupted the morals of the Roman race, and its inherent opposition to

long-standing religious traditions. Manichaeanism was also supported by Persia

at the time, compounding religious dissent with international politics.

Excepting Persian support, the reasons he disliked Manichaenism were equally

applicable, if not more so, to Christianity, his next target.

Great Persecution

Diocletian returned to Antioch in the autumn of 302. He ordered that the

deacon

Romanus of Caesarea

have his tongue removed for

defying the order of the courts and interrupting official sacrifices. Romanus

was then sent to prison, where he was executed on 17 November 303. Diocletian

believed that Romanus of Caesarea was arrogant, and he left the city for

Nicomedia in the winter, accompanied by Galerius. According to Lactantius,

Diocletian and Galerius entered into an argument over imperial policy towards

Christians while wintering at Nicomedia in 302. Diocletian argued that

forbidding Christians from the bureaucracy and military would be sufficient to

appease the gods, but Galerius pushed for extermination. The two men sought the

advice of the oracle

of

Apollo

at

Didyma

. The oracle responded that the impious

on Earth hindered Apollo’s ability to provide advice. Rhetorically Eusebius

records the Oracle as saying “The just on Earth…” These impious, Diocletian

was informed by members of the court, could only refer to the Christians of the

Empire. At the behest of his court, Diocletian acceded to demands for universal

persecution.

On 23 February 303, Diocletian ordered that the newly built church at

Nicomedia be razed. He demanded that its scriptures be burned, and seized its

precious stores for the treasury. The next day, Diocletian’s first “Edict

against the Christians” was published. The edict ordered the destruction of

Christian scriptures and places of worship across the Empire, and prohibited

Christians from assembling for worship. Before the end of February, a fire

destroyed part of the Imperial palace. Galerius convinced Diocletian that the

culprits were Christians, conspirators who had plotted with the

eunuchs

of the palace. An investigation was

commissioned, but no responsible party was found. Executions followed anyway,

and the palace eunuchs Dorotheus and

Gorgonius

were executed. One individual,

Peter Cubicularius

, was stripped, raised high,

and scourged. Salt and vinegar were poured in his wounds, and he was

slowly boiled

over an open flame. The

executions continued until at least 24 April 303, when six individuals,

including the bishop

Anthimus

, were

decapitated

. A second fire occurred sixteen

days after the first. Galerius left the city for Rome, declaring Nicomedia

unsafe. Diocletian would soon follow.

Although further persecutionary edicts followed, compelling the arrest of the

Christian clergy and universal acts of sacrifice, the persecutionary edicts were

ultimately unsuccessful; most Christians escaped punishment, and pagans too were

generally unsympathetic to the persecution. The

martyrs

‘ sufferings strengthened the resolve of

their fellow Christians. Constantius and Maximian did not apply the later

persecutionary edicts, and left the Christians of the West unharmed. Galerius

rescinded the edict in 311, announcing that the persecution had failed to bring

Christians back to traditional religion. The temporary apostasy of some

Christians, and the surrendering of scriptures, during the persecution played a

major role in the subsequent

Donatist

controversy. Within twenty-five years

of the persecution’s inauguration, the Christian Emperor Constantine would rule

the empire alone. He would reverse the consequences of the edicts, and return

all confiscated property to Christians. Under Constantine’s rule, Christianity

would become the Empire’s preferred religion. Diocletian was demonized by his

Christian successors: Lactantius intimated that Diocletian’s ascendancy heralded

the apocalypse, and in

Serbian mythology

, Diocletian is remembered as

Dukljan

, the

adversary

of

God.

Later life

Illness and abdication

Diocletian entered the city of Rome in the early winter of 303. On 20

November, he celebrated, with Maximian, the twentieth anniversary of his reign (vicennalia),

the tenth anniversary of the Tetrarchy (decennalia),

and a triumph for the war with Persia. Diocletian soon grew impatient with the

city, as the Romans acted towards him with what

Edward Gibbon

, following

Lactantius

, calls “licentious familiarity”. The

Roman people did not give enough deference to his supreme authority; it expected

him to act the part of an aristocratic ruler, not a monarchic one. On 20

December 303, Diocletian cut short his stay in Rome and left for the north. He

did not even perform the ceremonies investing him with his ninth consulate; he

did them in Ravenna

on 1 January 304 instead. There are

suggestions in the

Panegyrici Latini

and Lactantius’ account

that Diocletian arranged plans for his and Maximian’s future retirement of power

in Rome. Maximian, according to these accounts, swore to uphold Diocletian’s

plan in a ceremony in the

Temple of Jupiter

.

From Ravenna, Diocletian left for the Danube. There, possibly in Galerius’

company, he took part in a campaign against the Carpi. He contracted a minor

illness while on campaign, but his condition quickly worsened and he chose to

travel in a

litter

. In the late summer he left for

Nicomedia. On 20 November, he appeared in public to dedicate the opening of the

circus beside his palace. He collapsed soon after the ceremonies. Over the

winter of 304–5 he kept within his palace at all times. Rumors alleging that

Diocletian’s death was merely being kept secret until Galerius could come to

assume power spread through the city. On 13 December, he seemed to have finally

died. The city was sent into a mourning from which it was only retrieved by

public declarations of his survival. When Diocletian reappeared in public on 1

March 305, he was emaciated and barely recognizable.

Galerius arrived in the city later in March. According to Lactantius, he came

armed with plans to reconstitute the Tetrarchy, force Diocletian to step down,

and fill the Imperial office with men compliant to his will. Through coercion

and threats, he eventually convinced Diocletian to comply with his plan.

Lactantius also claims that he had done the same to Maximian at Sirmium. On 1

May 305, Diocletian called an assembly of his generals, traditional companion

troops, and representatives from distant legions. They met at the same hill, 5

kilometres (3.1 mi) out of Nicomedia, where Diocletian had been proclaimed

emperor. In front of a statue of Jupiter, his patron deity, Diocletian addressed

the crowd. With tears in his eyes, he told them of his weakness, his need for

rest, and his will to resign. He declared that he needed to pass the duty of

Empire on to someone stronger. He thus became the first Roman Emperor to

voluntarily abdicate his title.

Most in the crowd believed they knew what would follow;

Constantine

and Maxentius, the only adult sons

of a reigning Emperor, men who had long been preparing to succeed their fathers,

would be granted the title of Caesar. Constantine had traveled through Palestine

at the right hand of Diocletian, and was present at the palace in Nicomedia in

303 and 305. It is likely that Maxentius received the same treatment. In

Lactantius’ account, when Diocletian announced that he was to resign, the entire

crowd turned to face Constantine. It was not to be:

Severus

and

Maximin

were declared Caesars. Maximin appeared

and took Diocletian’s robes. On the same day, Severus received his robes from

Maximian in Milan. Constantius succeeded Maximian as Augustus of the West, but

Constantine and Maxentius were entirely ignored in the transition of power. This

did not bode well for the future security of the Tetrarchic system.

Retirement and death

Diocletian retired to his homeland,

Dalmatia

. He moved into the expansive

Diocletian’s Palace

, a heavily fortified

compound located by the small town of Spalatum on the shores of the

Adriatic Sea

, and near the large provincial

administrative center of

Salona

. The palace is preserved in great part

to this day and forms the historic core of the largest city of modern

Split

,

Croatia

.

Maximian retired to villas in

Campania

or

Lucania

. Their homes were distant from

political life, but Diocletian and Maximian were close enough to remain in

regular contact with each other. Galerius assumed the consular fasces in

308 with Diocletian as his colleague. In the autumn of 308, Galerius again

conferred with Diocletian at

Carnuntum

(Petronell-Carnuntum,

Austria

). Diocletian and Maximian were both

present on 11 November 308, to see Galerius appoint

Licinius

to be Augustus in place of Severus,

who had died at the hands of Maxentius. He ordered Maximian, who had attempted

to return to power after his retirement, to step down permanently. At Carnuntum

people begged Diocletian to return to the throne, to resolve the conflicts that

had arisen through Constantine’s rise to power and Maxentius’ usurpation.

Diocletian’s reply: “If you could show the

cabbage

that I planted with my own hands to

your emperor, he definitely wouldn’t dare suggest that I replace the peace and

happiness of this place with the storms of a never-satisfied greed.”

He lived on for three more years, spending his days in his palace gardens. He

saw his Tetrarchic system fail, torn by the selfish ambitions of his successors.

He heard of Maximian’s third claim to the throne, his forced suicide, his

damnatio memoriae

. In his own palace,

statues and portraits of his former companion emperor were torn down and

destroyed. Deep in despair and illness, Diocletian may have committed

suicide

. He died on 3 December 311.

Reforms

Tetrarchic and

ideological

Modern view of

Diocletian’s Palace

near

Salona

(in

Split

,

Croatia

)

Diocletian saw his work as that of a restorer, a figure of authority whose

duty it was to return the empire to peace, to recreate stability and justice

where barbarian hordes had destroyed it. He arrogated, regimented and

centralized political authority on a massive scale. In his policies, he enforced

an Imperial system of values on diverse and often unreceptive provincial

audiences. In the Imperial propaganda from the period, recent history was

perverted and minimized in the service of the theme of the Tetrarchs as

“restorers”. Aurelian’s achievements were ignored, the revolt of Carausius was

backdated to the reign of Gallienus, and it was implied that the Tetrarchs

engineered Aurelian’s defeat of the

Palmyrenes

; the period between Gallienus and

Diocletian was effectively erased. The history of the empire before the

Tetrarchy was portrayed as a time of civil war, savage despotism, and imperial

collapse. In those inscriptions that bear their names, Diocletian and his

companions are referred to as “restorers of the whole world”, men who succeeded

in “defeating the nations of the barbarians, and confirming the tranquility of

their world”. Diocletian was written up as the “founder of eternal peace”. The

theme of restoration was conjoined to an emphasis on the uniqueness and

accomplishments of the Tetrarchs themselves.

The cities where Emperors lived frequently in this period—Milan,

Trier

,

Arles

, Sirmium,

Serdica

,

Thessaloniki

, Nicomedia, and

Antioch

—were treated as alternate imperial

seats, to the exclusion of Rome and its senatorial elite. A new style of

ceremony was developed, emphasizing the distinction of the Emperor from all

other persons. The quasi-republican ideals of Augustus’

primus inter pares

were abandoned for all

but the Tetrarchs themselves. Diocletian took to wearing a gold crown and

jewels, and forbade the use of

purple cloth

to all but the Emperors. His

subjects were required to prostrate themselves in his presence (adoratio);

the most fortunate were allowed the privilege of kissing the hem of his robe (proskynesis,

προσκύνησις). Circuses and basilicas were designed to keep the face of the

Emperor perpetually in view, and always in a seat of authority. The emperor

became a figure of transcendent authority, a man beyond the grip of the masses.

His every appearance was stage-managed. This style of presentation was not

new—many of its elements were first seen in the reigns of Aurelian and

Severus—but it was only under the Tetrarchs that it was refined into an explicit

system.

Administrative

In keeping with his move from an ideology of republicanism to one of

autocracy, Diocletian’s council of advisers, his consilium, differed from

those of earlier Emperors. He destroyed the Augustan illusion of imperial

government as a cooperative affair between Emperor, Army, and Senate. In its

place he established an effectively autocratic structure, a shift later

epitomized in the institution’s name: it would be called a consistorium

(“consistory“),

not a council. Diocletian regulated his court by distinguishing separate

departments (scrina) for different tasks. From this structure came the

offices of different magistri, like the Magister officiorum

(“Master of offices”), and associated secretariats. These were men suited to

dealing with petitions, requests, correspondence, legal affairs, and foreign

embassies. Within his court Diocletian maintained a permanent body of legal

advisers, men with significant influence on his re-ordering of juridical

affairs. There were also two finance ministers, dealing with the separate bodies

of the public treasury and the private domains of the Emperor, and the

praetorian prefect, the most significant person of the whole. Diocletian’s

reduction of the Praetorian Guards to the level of a simple city garrison for

Rome lessened the military powers of the prefect, but the office retained much

civil authority. The prefect kept a staff of hundreds and managed affairs in all

segments of government: in taxation, administration, jurisprudence, and minor

military commands, the praetorian prefect was often second only to the emperor

himself.

Altogether, Diocletian effected a large increase in the number of bureaucrats

at the government’s command; Lactantius was to claim that there were now more

men using tax money than there were paying it. The historian Warren Treadgold

estimates that under Diocletian the number of men in the

civil service

doubled from 15,000 to 30,000.

The classicist

Roger Bagnall

estimated that there was one

bureaucrat for every 5–10,000 people in Egypt based on 400 or 800 bureaucrats

for 4 million inhabitants (no one knows the population of the province in 300

AD; Strabo 300 years earlier put it at 7.5 million, excluding Alexandria). (By

comparison, the ratio in

twelfth-century China

was one bureaucrat for

every 15,000 people.) Jones estimated 30,000 bureaucrats for an empire of 50–65

million inhabitants, which works out to approximately 1,667 or 2,167 inhabitants

per imperial official as averages empire-wide. The actual numbers of officials

and ratios per inhabitant varied, of course, per diocese depending on the number

of provinces and population within a diocese. Provincial and diocesan paid

officials (there were unpaid supernumeraries) numbered about 13–15,000 based on

their staff establishments as set by law. The other 50% were with the emperor(s)

in his or their Comitatus, with the praetorian prefects, with the grain supply

officials in the capital (later, the capitals, Rome and Constantinople),

Alexandria, and Carthage and officials from the central offices located in the

provinces.

To avoid the possibility of local usurpations, to facilitate a more efficient

collection of taxes and supplies, and to ease the enforcement of the law,

Diocletian doubled the number of

provinces

from fifty to almost one hundred. The

provinces were grouped into twelve

dioceses

, each governed by an appointed

official called a

vicarius

, or “deputy of the praetorian

prefects”. Some of the provincial divisions required revision, and were modified

either soon after 293 or early in the fourth century. Rome herself (including

her environs, as defined by a 100 miles (160 km)-radius

perimeter

around the City itself) was not under

the authority of the praetorian prefect, as she was to be administered by a City

Prefect of senatorial rank – the sole prestigious post with actual power

reserved exclusively for senators, except for some governors in Italy with the

titles of corrector and the proconsuls of Asia and Africa. The dissemination of

imperial law to the provinces was facilitated under Diocletian’s reign, because

Diocletian’s reform of the Empire’s provincial structure meant that there were

now a greater number of governors (praesides)

ruling over smaller regions and smaller populations. Diocletian’s reforms

shifted the governors’ main function to that of the presiding official in the

lower courts: whereas in the early Empire military and judicial functions were

the function of governor, and

procurators

had supervised taxation; under the

new system vicarii and governors were responsible for justice and

taxation, and a new class of

duces (“dukes“),

acting independently of the civil service, had military command. These dukes

sometimes administered two or three of the new provinces created by Diocletian,

and had forces ranging from two thousand to more than twenty thousand men. In

addition to their roles as judges and tax collectors, governors were expected to

maintain the postal service (cursus

publicus) and ensure that town councils fulfilled their duties.

This curtailment of governors’ powers as the Emperors’ representatives may

have lessened the political dangers of an all-too-powerful class of Imperial

delegates, but it also severely limited governors’ ability to oppose local

landed elites. On one occasion, Diocletian had to exhort a proconsul of Africa

not to fear the consequences of treading on the toes of the local magnates of

senatorial rank. If a governor of senatorial rank himself felt these pressures,

one can imagine the difficulties faced by a mere praeses.

Legal

As with most Emperors, much of Diocletian’s daily routine rotated around

legal affairs—responding to appeals and petitions, and delivering decisions on

disputed matters. Rescripts, authoritative interpretations issued by the Emperor

in response to demands from disputants in both public and private cases, were a

common duty of second- and third-century Emperors. Diocletian was awash in

paperwork, and was nearly incapable of delegating his duties. It would have been

seen as a dereliction of duty to ignore them. Diocletian’s praetorian

prefects—Afranius Hannibalianus, Julius Asclepiodotus, and

Aurelius Hermogenianus

—aided in regulating the

flow and presentation of such paperwork, but the deep legalism of Roman culture

kept the workload heavy. Emperors in the forty years preceding Diocletian’s

reign had not managed these duties so effectively, and their output in attested

rescripts is low. Diocletian, by contrast, was prodigious in his affairs: there

are around 1,200 rescripts in his name still surviving, and these probably

represent only a small portion of the total issue. The sharp increase in the

number of edicts and rescripts produced under Diocletian’s rule has been read as

evidence of an ongoing effort to realign the whole Empire on terms dictated by

the imperial center.

Under the governance of the

jurists

Gregorius, Aurelius Arcadius Charisius,

and Hermogenianus, the imperial government began issuing official books of

precedent

, collecting and listing all the

rescripts that had been issued from the reign of

Hadrian

(r. 117–38) to the reign of Diocletian.

The

Codex Gregorianus

includes rescripts up to 292,

which the

Codex Hermogenianus

updated with a

comprehensive collection of rescripts issued by Diocletian in 293 and 294.

Although the very act of codification was a radical innovation, given the

precedent-based design of the Roman legal system, the jurists were generally

conservative, and constantly looked to past Roman practice and theory for

guidance. They were probably given more free rein over their codes than the

later compilers of the

Codex Theodosianus

(438) and

Codex Justinianus

(529) would have.

Gregorius and Hermogenianus’ codices lack the rigid structuring of later codes,

and were not published in the name of the emperor, but in the names of their

compilers.

After Diocletian’s reform of the provinces, governors were called iudex,

or judge

. The governor became responsible for his

decisions first to his immediate superiors, as well as to the more distant

office of the Emperor. It was most likely at this time that judicial records

became verbatim accounts of what was said in trial, making it easier to

determine bias or improper conduct on the part of the governor. With these

records and the Empire’s universal right of

appeal

, Imperial authorities probably had a

great deal of power to enforce behavior standards for their judges. In spite of

Diocletian’s attempts at reform, the provincial restructuring was far from

clear, especially when citizens appealed the decisions of their governors.

Proconsuls, for example, were often both judges of first instance and appeal,

and the governors of some provinces took appellant cases from their neighbors.

It soon became impossible to avoid taking some cases to the Emperor for

arbitration and judgment. Diocletian’s reign marks the end of the classical

period of Roman law. Where Diocletian’s system of rescripts shows an adherence

to classical tradition, Constantine’s law is full of Greek and eastern

influences.

Military

It is archaeologically difficult to distinguish Diocletian’s fortifications

from those of his successors and predecessors. The Devil’s Dyke, for example,

the Danubian earthworks traditionally attributed to Diocletian, cannot even be

securely dated to a particular century. The most that can be said about built

structures under Diocletian’s reign is that he rebuilt and strengthened forts at

the Upper Rhine frontier (where he followed the works made under

Probus

‘s reign, both along the

Lake Constance

–Basel

as well as along the Rhine–Iller–Danube

line), in Egypt, and on the frontier with Persia. Beyond that, much discussion

is speculative, and reliant on the broad generalizations of written sources.

Diocletian and the Tetrarchs had no consistent plan for frontier advancement,

and records of raids and forts built across the frontier are likely to indicate

only temporary claims. The

Strata Diocletiana

, which ran from the

Euphrates to Palmyra and northeast Arabia, is the classic Diocletianic frontier

system, consisting of an outer road followed by tightly spaced forts followed by

further fortifications in the rear. In an attempt to resolve the difficulty and

slowness of transmitting orders to the frontier, the new capitals of the

Tetrarchic era were all much closer to the Empire’s frontiers than Rome had

been: Trier sat on the Rhine, Sirmium and Serdica were close to the Danube,

Thessaloniki was on the route leading eastward, and Nicomedia and Antioch were

important points in dealings with Persia.

Lactantius criticized Diocletian for an excessive increase in troop sizes,

declaring that “each of the four [Tetrarchs] strove to have a far larger number

of troops than previous emperors had when they were governing the state alone”.

The fifth-century pagan

Zosimus

, by contrast, praised Diocletian for

keeping troops on the borders, rather than keeping them in the cities, as

Constantine was held to have done. Both these views had some truth to them,

despite the biases of their authors: Diocletian and the Tetrarchs did greatly

expand the army, and the growth was mostly in frontier regions, although it is

difficult to establish the precise details of these shifts given the weakness of

the sources. The army expanded to about 580,000 men from a 285 strength of

390,000, of which 310,000 men were stationed in the East, most of whom manned

the Persian frontier. The navy’s forces increased from approximately 45,000 men

to approximately 65,000 men.

Diocletian’s expansion of the army and civil service meant that the Empire’s

tax burden grew. Since military upkeep took the largest portion of the imperial

budget, any reforms here would be especially costly. The proportion of the adult

male population, excluding slaves, serving in the army increased from roughly 1

in 25 to 1 in 15, an increase judged excessive by some modern commentators.

Official troop allowances were kept to low levels, and the mass of troops often

resorted to extortion or the taking of civilian jobs. Arrears became the norm

for most troops. Many were even given payment in kind in place of their

salaries. Were he unable to pay for his enlarged army, there would likely be

civil conflict, potentially open revolt. Diocletian was led to devise a new

system of taxation.

Economic

Taxation

In the early Empire (30 BC- AD 235) the Roman government paid for what it

needed in gold and silver. The coinage was stable. Requisition, forced purchase,

was used to supply armies on the march. During the third century crisis

(235–285), the government resorted to requisition rather than payment in debased

coinage, since it could never be sure of the value of money. Requisition was

nothing more or less than seizure. Diocletian made requisition into tax. He

introduced an extensive new tax system based on heads (capita) and land (iuga)

and tied to a new, regular census of the Empire’s population and wealth. Census

officials traveled throughout the Empire, assessed the value of labor and land

for each landowner, and joined the landowners’ totals together to make city-wide

totals of capita and iuga. The iugum was not a consistent

measure of land, but varied according to the type of land and crop, and the

amount of labor necessary for sustenance. The caput was not consistent

either: women, for instance, were often valued at half a caput, and

sometimes at other values. Cities provided animals, money, and manpower in

proportion to its capita, and grain in proportion to its iuga.

Most taxes were due on each year on 1 September, and levied from individual

landowners by

decuriones

(decurions). These decurions,

analogous to city councilors, were responsible for paying from their own pocket

what they failed to collect. Diocletian’s reforms also increased the number of

financial officials in the provinces: more rationales and magistri

privatae are attested under Diocletian’s reign than before. These officials

managed represented the interests of the fisc, which collected taxes in gold,

and the Imperial properties. Fluctuations in the value of the currency made

collection of taxes in kind the norm, although these could be converted into

coin. Rates shifted to take inflation into account. In 296, Diocletian issued an

edict reforming census procedures. This edict introduced a general five-year

census for the whole Empire, replacing prior censuses that had operated at

different speeds throughout the Empire. The new censuses would keep up with

changes in the values of capita and iuga.

Italy, which had long been exempt from taxes, was included in the tax system

from 290/291 as other provinces. The city of Rome itself and the surrounding

Suburbicarian diocese

(where Roman senators

held the bulk of their landed property), however, remained exempt.

Diocletian’s edicts emphasized the common liability of all taxpayers. Public

records of all taxes were made public. The position of decurion, member

of the city council, had been an honor sought by wealthy aristocrats and the

middle classes who displayed their wealth by paying for city amenities and

public works. Decurions were made liable for any shortfall in the amount of tax

collected. Many tried to find ways to escape the obligation.

Currency and inflation

Aurelian’s attempt to reform the currency had failed; the denarius was dead.

Diocletian restored the three-metal coinage and issued better quality pieces.

The new system consisted of five coins: the aureus/solidus,

a gold coin weighing, like its predecessors, one-sixtieth of a pound; the

argenteus

, a coin weighing one ninety-sixth

of a pound and containing ninety-five percent pure silver; the

follis

, sometimes referred to as the

laureatus A, which is a copper coin with added silver struck at the rate of

thirty-two to the pound; the radiatus, a small copper coin struck at the

rate of 108 to the pound, with no added silver; and a coin known today as the

laureatus B, a smaller copper coin struck at the rate of 192 to the pound.

Since the nominal values of these new issues were lower than their intrinsic

worth as metals, the state was minting these coins at a loss. This practice

could be sustained only by requisitioning precious metals from private citizens

in exchange for state-minted coin (of a far lower value than the price of the

precious metals requisitioned).

By 301, however, the system was in trouble, strained by a new bout of

inflation. Diocletian therefore issued his Edict on Coinage, an act

re-tariffing all debts so that the

nummus

, the most common coin in

circulation, would be worth half as much. In the edict, preserved in an

inscription from the city of

Aphrodisias

in

Caria

(near

Geyre

, Turkey), it was declared that all debts

contracted before 1 September 301 must be repaid at the old standards, while all

debts contracted after that date would be repaid at the new standards. It

appears that the edict was made in an attempt to preserve the current price of

gold and to keep the Empire’s coinage on silver, Rome’s traditional metal

currency. This edict risked giving further momentum to inflationary trends, as

had happened after Aurelian’s currency reforms. The government’s response was to

issue a price freeze.

The

Edict on Maximum Prices

(Edictum De

Pretiis Rerum Venalium) was issued two to three months after the coinage

edict, somewhere between 20 November and 10 December 301. The best-preserved

Latin inscription surviving from the

Greek East

,[

the edict survives in many versions, on materials as varied as wood, papyrus,

and stone. In the edict, Diocletian declared that the current pricing crisis

resulted from the unchecked greed of merchants, and had resulted in turmoil for

the mass of common citizens. The language of the edict calls on the people’s

memory of their benevolent leaders, and exhorts them to enforce the provisions

of the edict, and thereby restore perfection to the world. The edict goes on to

list in detail over one thousand goods and accompanying retail prices not to be

exceeded. Penalties are laid out for various pricing transgressions.

In the most basic terms, the edict was ignorant of the law of

supply and demand

: it ignored the fact that

prices might vary from region to region according to product availability, and

it ignored the impact of transportation costs in the retail price of goods. In

the judgment of the historian David Potter, the edict was “an act of economic

lunacy”. Inflation, speculation, and monetary instability continued, and a black

market arose to trade in goods forced out of official markets. The edict’s

penalties were applied unevenly across the empire (some scholars believe they

were applied only in Diocletian’s domains), widely resisted, and eventually

dropped, perhaps within a year of the edict’s issue. Lactantius has written of

the perverse accompaniments to the edict; of goods withdrawn from the market, of

brawls over minute variations in price, of the deaths that came when its

provisions were enforced. His account may be true, but it seems to modern

historians exaggerated and hyperbolic, and the impact of the law is recorded in

no other ancient source.

Legacy

The historian

A.H.M. Jones

observed that “It is perhaps

Diocletian’s greatest achievement that he reigned twenty-one years and then

abdicated voluntarily, and spent the remaining years of his life in peaceful

retirement.” Diocletian was one of the few Emperors of the third and fourth

centuries to die naturally, and the first in the history of the Empire to retire

voluntarily. Once he retired, however, his Tetrarchic system collapsed. Without

the guiding hand of Diocletian, the Empire fell into civil wars. Stability

emerged after the defeat of Licinius by Constantine in 324. Under the Christian

Constantine, Diocletian was maligned. Constantine’s rule, however, validated

Diocletian’s achievements and the autocratic principle he represented: the

borders remained secure, in spite of Constantine’s large expenditure of forces

during his civil wars; the bureaucratic transformation of Roman government was

completed; and Constantine took Diocletian’s court ceremonies and made them even

more extravagant.

Constantine ignored those parts of Diocletian’s rule that did not suit him.

Diocletian’s policy of preserving a stable silver coinage was abandoned, and the

gold

solidus

became the Empire’s primary

currency instead. Diocletian’s

persecution of Christians

was repudiated and

changed to a policy of toleration and then favoritism. Christianity eventually

became the official religion in 381. Constantine would claim to have the same

close relationship with the Christian God as Diocletian claimed to have with

Jupiter. Most importantly, Diocletian’s tax system and administrative reforms

lasted, with some modifications, until the advent of the Muslims in the 630s.

The combination of state autocracy and state religion was instilled in much of

Europe, particularly in the lands which adopted Orthodox Christianity.

In addition to his administrative and legal impact on history, the Emperor

Diocletian is considered to be the founder of the city of

Split

in modern-day

Croatia

. The city itself grew around the

heavily fortified

Diocletian’s Palace

the Emperor had built in

anticipation of his retirement.

|