|

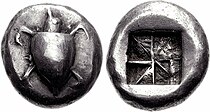

Greek City.

Bronze 10mm (0.87 grams) Struck circa 250-100 B.C.

Head of Hercules right.

Bow in bow-case and club.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

The history of

Ancient Greek

coinage can be divided (along

with most other Greek art forms) into four periods, the

Archaic

, the

Classical

, the

Hellenistic

and the

Roman

. The Archaic period extends from the

introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the

7th century BC

until the

Persian Wars

in about 480 BC. The Classical

period then began, and lasted until the conquests of

Alexander the Great

in about 330 BC, which

began the Hellenistic period, extending until the

Roman

absorption of the Greek world in the 1st

century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several

more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are

called

Roman provincial coins

or Greek Imperial Coins.

Ancient Greek coins of all four periods span over a period of more than ten

centuries.

Weight

standards and denominations

Above: Six rod-shaped obeloi (oboloi) displayed at the

Numismatic Museum of Athens

,

discovered at

Heraion of Argos

. Below: grasp[1]

of six oboloi forming one drachma

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC, known as

Phanes’ coin

. Obverse:

Stag

grazing, ΦΑΝΕΩΣ (retrograde).

Reverse: Two incuse punches.

The basic standards of the Ancient Greek monetary system were the

Attic

standard, based on the Athenian

drachma

of 4.3 grams of silver and the

Corinthian

standard based on the

stater

of 8.6 grams of silver, that was

subdivided into three silver drachmas of 2.9 grams. The word

drachm

(a) means “a handful”, literally “a

grasp”. Drachmae were divided into six

obols

(from the Greek word for a

spit

), and six spits made a “handful”. This

suggests that before coinage came to be used in Greece, spits in

prehistoric times

were used as measures of

daily transaction. In archaic/pre-numismatic times iron was valued for making

durable tools and weapons, and its casting in spit form may have actually

represented a form of transportable

bullion

, which eventually became bulky and

inconvenient after the adoption of precious metals. Because of this very aspect,

Spartan

legislation famously forbade issuance

of Spartan coin, and enforced the continued use of iron spits so as to

discourage avarice and the hoarding of wealth. In addition to its original

meaning (which also gave the

euphemistic

diminutive

“obelisk“,

“little spit”), the word obol (ὀβολός, obolós, or ὀβελός,

obelós) was retained as a Greek word for coins of small value, still used as

such in Modern Greek

slang (όβολα, óvola,

“monies”).

The obol was further subdivided into tetartemorioi (singular

tetartemorion) which represented 1/4 of an obol, or 1/24 of a drachm. This

coin (which was known to have been struck in

Athens

,

Colophon

, and several other cities) is

mentioned by Aristotle

as the smallest silver coin.:237

Various multiples of this denomination were also struck, including the

trihemitetartemorion (literally three half-tetartemorioi) valued at 3/8 of

an obol.:

| Denominations of silver drachma |

| Image |

Denomination |

Value |

Weight |

|

|

Dekadrachm |

10 drachmas |

43 grams |

|

|

Tetradrachm |

4 drachmas |

17.2 grams |

|

|

Didrachm |

2 drachmas |

8.6 grams |

|

|

Drachma |

6 obols |

4.3 grams |

|

|

Tetrobol |

4 obols |

2.85 grams |

|

|

Triobol (hemidrachm) |

3 obols |

2.15 grams |

|

|

Diobol |

2 obols |

1.43 grams |

|

|

Obol |

4 tetartemorions |

0.72 grams |

|

|

Tritartemorion |

3 tetartemorions |

0.54 grams |

|

|

Hemiobol |

2 tetartemorions |

0.36 grams |

|

|

Trihemitartemorion |

3/2 tetartemorions |

0.27 grams |

|

|

Tetartemorion |

|

0.18 grams |

|

|

Hemitartemorion |

½ tetartemorion |

0.09 grams |

Archaic period

Archaic coinage

Uninscribed

electrum

coin from

Lydia

, 6th century BCE.

Obverse: lion head and sunburst Reverse: plain square

imprints, probably used to standardise weight

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC. Obverse:

Forepart of stag. Reverse: Square incuse punch.

The first coins were issued in either Lydia or Ionia in Asia Minor at some

time before 600 BC, either by the non-Greek Lydians for their own use or perhaps

because Greek mercenaries wanted to be paid in precious metal at the conclusion

of their time of service, and wanted to have their payments marked in a way that

would authenticate them. These coins were made of

electrum

, an alloy of gold and silver that was

highly prized and abundant in that area. By the middle of the 6th century BC,

technology had advanced, making the production of pure gold and silver coins

simpler. Accordingly, King

Croesus

introduced a bi-metallic standard that

allowed for coins of pure gold and pure silver to be struck and traded in the

marketplace.

Coins of Aegina

Silver

stater

of Aegina, 550-530 BC.

Obv.

Sea turtle

with large pellets

down center. Rev. incuse square with eight sections. After the

end of the

Peloponnesian War

, 404 BC, Sea

turtle was replaced by the land

tortoise

.

Silver

drachma

of Aegina, 404-340 BC.

Obverse: Land

tortoise

. Reverse: inscription

AΙΓ[INAΤΟΝ] ([of the] Aeg[inetans]) “Aegina” and dolphin.

The Greek world was divided into more than two thousand self-governing

city-states (in

Greek

, poleis), and more than half of

them issued their own coins. Some coins circulated widely beyond their polis,

indicating that they were being used in inter-city trade; the first example

appears to have been the silver stater or didrachm of

Aegina

that regularly turns up in hoards in

Egypt

and the

Levant

, places which were deficient in silver

supply. As such coins circulated more widely, other cities began to mint coins

to this “Aeginetan” weight standard of (6.1 grams to the drachm), other cities

included their own symbols on the coins. This is not unlike present day

Euro coins, which are recognisably from a particular country, but

usable all over the

Euro zone

.

Athenian coins, however, were struck on the “Attic” standard, with a drachm

equaling 4.3 grams of silver. Over time, Athens’ plentiful supply of silver from

the mines at

Laurion

and its increasing dominance in trade

made this the pre-eminent standard. These coins, known as “owls” because of

their central design feature, were also minted to an extremely tight standard of

purity and weight. This contributed to their success as the premier trade coin

of their era. Tetradrachms on this weight standard continued to be a widely used

coin (often the most widely used) through the classical period. By the time of

Alexander the Great

and his

Hellenistic successors

, this large denomination

was being regularly used to make large payments, or was often saved for

hoarding.

Classical period

A

Syracusan

tetradrachm

(c. 415–405

BC)

Obverse: head of the

nymph

Arethusa

, surrounded by

four swimming

dolphins

and a

rudder

Reverse: a racing

quadriga

, its

charioteer

crowned by the

goddess

Victory

in flight.

Tetradrachm of Athens, (5th century BC)

Obverse: a portrait of

Athena

, patron goddess of

the city, in

helmet

Reverse: the owl of Athens, with an

olive

sprig and the

inscription “ΑΘΕ”, short for ΑΘΕΝΑΙΟΝ, “of the

Athenians

“

The

Classical period

saw Greek coinage reach a high

level of technical and aesthetic quality. Larger cities now produced a range of

fine silver and gold coins, most bearing a portrait of their patron god or

goddess or a legendary hero on one side, and a symbol of the city on the other.

Some coins employed a visual pun: some coins from

Rhodes

featured a

rose, since the Greek word for rose is rhodon. The use of

inscriptions on coins also began, usually the name of the issuing city.

The wealthy cities of Sicily produced some especially fine coins. The large

silver decadrachm (10-drachm) coin from

Syracuse

is regarded by many collectors as the

finest coin produced in the ancient world, perhaps ever. Syracusan issues were

rather standard in their imprints, one side bearing the head of the nymph

Arethusa

and the other usually a victorious

quadriga

. The

tyrants of Syracuse

were fabulously rich, and

part of their

public relations

policy was to fund

quadrigas

for the

Olympic chariot race

, a very expensive

undertaking. As they were often able to finance more than one quadriga at a

time, they were frequent victors in this highly prestigious event.

Syracuse was one of the epicenters of numismatic art during the classical

period. Led by the engravers Kimon and Euainetos, Syracuse produced some of the

finest coin designs of antiquity.

Hellenistic period

Gold 20-stater

of

Eucratides I

, the largest gold coin

ever minted in Antiquity.

Drachma of

Alexandria

, 222-235 AD. Obverse:

Laureate head of

Alexander Severus

, KAI(ΣΑΡ) MAP(ΚΟΣ)

AYP(ΗΛΙΟΣ) ΣЄY(ΑΣΤΟΣ) AΛЄΞANΔPOΣ ЄYΣЄ(ΒΗΣ). Reverse: Bust of

Asclepius

.

The Hellenistic period was characterized by the spread of Greek

culture across a large part of the known world. Greek-speaking kingdoms were

established in Egypt

and

Syria

, and for a time also in

Iran and as far east as what is now

Afghanistan

and northwestern

India

. Greek traders spread Greek coins across

this vast area, and the new kingdoms soon began to produce their own coins.

Because these kingdoms were much larger and wealthier than the Greek city states

of the classical period, their coins tended to be more mass-produced, as well as

larger, and more frequently in gold. They often lacked the aesthetic delicacy of

coins of the earlier period.

Still, some of the

Greco-Bactrian

coins, and those of their

successors in India, the

Indo-Greeks

, are considered the finest examples

of

Greek numismatic art

with “a nice blend of

realism and idealization”, including the largest coins to be minted in the

Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by

Eucratides

(reigned 171–145 BC), the largest

silver coin by the Indo-Greek king

Amyntas Nikator

(reigned c. 95–90 BC). The

portraits “show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland

depictions of their royal contemporaries further West” (Roger Ling, “Greece and

the Hellenistic World”).

The most striking new feature of Hellenistic coins was the use of portraits

of living people, namely of the kings themselves. This practice had begun in

Sicily, but was disapproved of by other Greeks as showing

hubris

(arrogance). But the kings of

Ptolemaic Egypt

and

Seleucid Syria

had no such scruples: having

already awarded themselves with “divine” status, they issued magnificent gold

coins adorned with their own portraits, with the symbols of their state on the

reverse. The names of the kings were frequently inscribed on the coin as well.

This established a pattern for coins which has persisted ever since: a portrait

of the king, usually in profile and striking a heroic pose, on the obverse, with

his name beside him, and a coat of arms or other symbol of state on the reverse.

Minting

All Greek coins were

handmade

, rather than machined as modern coins

are. The design for the obverse was carved (in

incuso

) into a block of bronze or possibly

iron, called a

die

. The design of the reverse was carved into

a similar punch. A blank disk of gold, silver, or electrum was cast in a mold

and then, placed between these two and the punch struck hard with a hammer,

raising the design on both sides of the coin.

Coins as

a symbol of the city-state

Coins of Greek city-states depicted a unique

symbol

or feature, an early form of

emblem

, also known as

badge

in numismatics, that represented their

city and promoted the prestige of their state. Corinthian stater for example

depicted pegasus

the mythological winged stallion, tamed

by their hero

Bellerophon

. Coins of

Ephesus

depicted the

bee

sacred to

Artemis

. Drachmas of Athens depicted the

owl of Athena

. Drachmas of

Aegina

depicted a

chelone

. Coins of

Selinunte

depicted a “selinon” (σέλινον

– celery

). Coins of

Heraclea

depicted

Heracles

. Coins of

Gela depicted a man-headed bull, the personification of the river

Gela

. Coins of

Rhodes

depicted a “rhodon” (ῥόδον[8]

– rose

). Coins of

Knossos

depicted the

labyrinth

or the mythical creature

minotaur

, a symbol of the

Minoan Crete

. Coins of

Melos

depicted a “mēlon” (μήλον –

apple

). Coins of

Thebes

depicted a Boeotian shield.

Corinthian stater with

pegasus

Coin of

Rhodes

with a

rose

Didrachm of

Selinunte

with a

celery

Coin of

Ephesus

with a

bee

Stater of

Olympia

depicting

Nike

Coin of

Melos

with an

apple

Obolus from

Stymphalia

with a

Stymphalian bird

Coin of

Thebes

with a Boeotian shield

Coin of Gela

with a man-headed bull,

the personification of the river

Gela

Didrachm of

Knossos

depicting the

Minotaur

Commemorative coins

Dekadrachm

of

Syracuse

[disambiguation

needed]. Head of Arethusa or queen

Demarete. ΣΥΡΑΚΟΣΙΟΝ (of the Syracusians), around four dolphins

The use of

commemorative coins

to celebrate a victory or

an achievement of the state was a Greek invention. Coins are valuable, durable

and pass through many hands. In an age without newspapers or other mass media,

they were an ideal way of disseminating a political message. The first such coin

was a commemorative decadrachm issued by

Athens

following the Greek victory in the

Persian Wars

. On these coins that were struck

around 480 BC, the owl

of Athens, the goddess

Athena

‘s sacred bird, was depicted facing the

viewer with wings outstretched, holding a spray of olive leaves, the

olive tree

being Athena’s sacred plant and also

a symbol of peace and prosperity. The message was that Athens was powerful and

victorious, but also peace-loving. Another commemorative coin, a silver

dekadrachm known as ” Demareteion”, was minted at

Syracuse

at approximately the same time to

celebrate the defeat of the

Carthaginians

. On the obverse it bears a

portrait of

Arethusa

or queen Demarete.

Ancient Greek coins

today

Collections of Ancient Greek coins are held by museums around the world, of

which the collections of the

British Museum

, the

American Numismatic Society

, and the

Danish National Museum

are considered to be the

finest. The American Numismatic Society collection comprises some 100,000

ancient Greek coins from many regions and mints, from Spain and North Africa to

Afghanistan. To varying degrees, these coins are available for study by

academics and researchers.

There is also an active collector market for Greek coins. Several auction

houses in Europe and the United States specialize in ancient coins (including

Greek) and there is also a large on-line market for such coins.

Hoards of Greek coins are still being found in Europe, Middle East, and North

Africa, and some of the coins in these hoards find their way onto the market.

Coins are the only art form from the Ancient world which is common enough and

durable enough to be within the reach of ordinary collectors.

HERCULES – This celebrated

of mythological romance was at first called Alcides, but received the name of

Hercules, or Heracles, from the Pythia of Delphos. Feigned by the poets of

antiquity to have been a son of “the Thunderer,” but born of an earthly mother,

he was exposed, through Juno’s implacable hatred to him as the offspring of

Alemena, to a course of perils, which commenced whilst he was yet in his cradle,

and under each of which he seemed to perish, but as constantly proved

victorious.

At

length finishing his allotted career with native valor and generosity, though

too frequently the submissive agent of the meanness and injustice of others, he

perished self-devotedly on the funeral pile, which was lighted on Mount Oeta.

Jupiter raised his heroic progeny to the skies; and Hercules was honored by the

pagan world, as the most illustrious of deified mortals. The extraordinary

enterprises cruelly imposed upon, but gloriously achieved, by this famous

demigod, are to be found depicted, not only on Greek coins, but also on the

Roman series both consular and imperial. The first, and one of the most

dangerous, of undertakings, well-known under the name of the twelve labors of

Hercules, was that of killing the huge lion of Nemea; on which account the

intrepid warrior is represented, clothes in the skin of that forest monarch; he

also bears uniformly a massive club, sometimes without any other arms, but at

others with a bow and quiver of arrows. On a denarius of the Antia gens he is

represented walking with trophy and club.

When his head alone is typified, as in Mucia gens, it is covered with the lion’s

spoils, in which distinctive decoration he was imitated by many princes, and

especially by those who claimed descent from him – as for example, the kings of

Macedonia, and the successors of Alexander the Great. Among the Roman emperors

Trajan is the first whose coins exhibit the figure and attributes of Hercules.

Ancient Greece is the civilization belonging to the period of

Greek history

lasting from the

Archaic period

of the 8th to 6th centuries BC

to 146 BC and the

Roman

conquest of

Greece

after the

Battle of Corinth

. At the center of this time

period is Classical Greece

, which flourished during the

5th to 4th centuries BC, at first under

Athenian

leadership successfully repelling the

military threat of

Persian invasion

. The

Athenian Golden Age

ends with the defeat of

Athens at the hands of Sparta

in the

Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Following the conquests of

Alexander the Great

,

Hellenistic civilization

flourished from

Central Asia to the western end of the

Mediterranean Sea.

Classical

Greek culture

had a powerful influence on the

Roman

Empire, which carried a version of it to many parts of the

Mediterranean region

and

Europe,

for which reason Classical Greece is generally considered to be the seminal

culture which provided the foundation of

Western civilization

.

Chronology

There are no fixed or universally agreed upon dates for the beginning or the

end of

Classical Antiquity

. It is typically taken to

last from the 8th century BC until the 6th century AD, or for about 1,300 years.

Classical Antiquity in Greece is preceded by the

Greek Dark Ages (c.1100-c.750 BC), archaeologically characterised by

the

protogeometric

and

geometric style

of designs on pottery,

succeeded by the

Orientalizing Period

, a strong influence of

Syro-Hittite

,

Assyrian

,

Phoenician

and

Egyptian

cultures.

Traditionally, the

Archaic period

of ancient Greece is taken in

the wake of this strong Orientalizing influence during the 8th century BC, which

among other things brought the

alphabetic script

to Greece, marking the

beginning of Greek literature (Homer,

Hesiod).

The Archaic period gives way to the

Classical period

around 500 BC, in turn

succeeded by the Hellenistic period

at the death of

Alexander the Great

in 323 BC.

The history of Greece

during Classical Antiquity

may thus be subdivided into the following periods

- The

Archaic period

(c.750-c.500 BC) follows, in

which artists made larger free-standing

sculptures

in stiff, hieratic poses with

the dreamlike ‘archaic

smile‘. The Archaic period is often taken to end with the

overthrow of the last tyrant of

Athens

in 510 BC.

- The Classical period (c.500-323 BC) is characterised by a style which

was considered by later observers to be exemplary (i.e. ‘classical’)—for

instance the Parthenon

. Politically, the Classical

Period was dominated by

Athens

and the

Delian League during the 5th century, displaced by

Spartan hegemony

during the early 4th

century BC, before power shifted to

Thebes

and the

Boeotian League

and finally to the

League of Corinth

led by

Macedon

.

- The Hellenistic period (323-146 BC) is when Greek culture and power

expanded into the near and

middle east

. This period begins with the

death of Alexander and ends with the Roman conquest.

- Roman Greece

, the period between Roman

victory over the

Corinthians

at the

Battle of Corinth in

146 BC and the

establishment of Byzantium

by

Constantine

as the capital of the

Roman Empire in 330 AD.

- the

final phase of Antiquity

is the period of

Christianization

during the later 4th to

early 6th centuries, taken to be complete with the closure of the

Neoplatonic

Academy

by

Justinian I in 529 AD.

Historiography

The historical period of ancient Greece is unique in world history as the

first period attested directly in proper

historiography, while earlier ancient history or

proto-history

is known by much more

circumstantial evidence, such as annals or king lists, and pragmatic epigraphy.

Herodotus is widely known as the “father of history”, his

Histories

being eponymous of the entire

field

. Written between the 450s and 420s BC,

the scope of Herodotus’ work reaches about a century into the past, discussing

6th-century historical figures such as

Darius I of Persia,

Cambyses II and Psamtik III

, and alludes to some 8th-century

ones such as Candaules

.

Herodotus was succeeded by authors such as

Thucydides, Xenophon

,

Demosthenes, Plato

and

Aristotle.

Most of these authors were either

Athenians

or pro-Athenians, which is why far

more is known about the history and politics of Athens than of many other

cities. Their scope is further limited by a focus on political, military and

diplomatic history, ignoring economic and social history.

History

Archaic period

In the 8th century BC, Greece began to emerge from the Dark Ages which

followed the fall of the Mycenaean civilization. Literacy had been lost and

Mycenaean script

forgotten, but the Greeks

adopted the Phoenician alphabet

, modifying it to create the

Greek alphabet. From about the 9th century BC written records begin

to appear.[6]

Greece was divided into many small self-governing communities, a pattern largely

dictated by Greek geography, where every island, valley and plain is cut off

from its neighbours by the sea or mountain ranges.[7]

The Lelantine War

(c.710-c.650 BC) was an ongoing

conflict with the distinction of being the earliest documented war of the

ancient Greek period. It was fought between the important

poleis

(city-states)

of Chalcis

and Eretria

over the fertile Lelantine plain of

Euboea.

Both cities seem to have suffered a decline as result of the long war, though

Chalcis was the nominal victor.

A mercantile class

rose in the first half of the

7th century, shown by the introduction of

coinage

in about 680 BC.[citation

needed] This seems to have introduced tension to many

city-states. The

aristocratic

regimes which generally governed

the poleis were threatened by the new-found wealth of merchants, who in turn

desired political power. From 650 BC onwards, the aristocracies had to fight not

to be overthrown and replaced by

populist

tyrants

. The word derives from the

non-pejorative

Greek τύραννος tyrannos,

meaning ‘illegitimate ruler’, although this was applicable to both good and bad

leaders alike.

A growing population and shortage of land also seems to have created internal

strife between the poor and the rich in many city-states. In

Sparta,

the

Messenian Wars resulted in the conquest of

Messenia

and enserfment of the Messenians, beginning in the latter half of the 8th

century BC, an act without precedent or antecedent in ancient Greece. This

practice allowed a social revolution to occur.

The subjugated population, thenceforth known as

helots,

farmed and laboured for Sparta, whilst every Spartan male citizen became a

soldier of the

Spartan Army

in a permanently militarized

state. Even the elite were obliged to live and train as soldiers; this equality

between rich and poor served to defuse the social conflict. These reforms,

attributed to the shadowy

Lycurgus of Sparta, were probably complete by 650 BC.

Athens suffered a land and agrarian crisis in the late 7th century, again

resulting in civil strife. The

Archon

(chief magistrate)

Draco

made severe reforms to the law code in

621 BC (hence “draconian“),

but these failed to quell the conflict. Eventually the moderate reforms of

Solon

(594 BC), improving the lot of the poor but firmly entrenching the aristocracy

in power, gave Athens some stability.

The Greek world in the mid 6th century BC.

By the 6th century BC several cities had emerged as dominant in Greek

affairs: Athens, Sparta,

Corinth

, and

Thebes

. Each of them had brought the

surrounding rural areas and smaller towns under their control, and Athens and

Corinth had become major maritime and mercantile powers as well.

Rapidly increasing population in the 8th and 7th centuries had resulted in

emigration of many Greeks to form

colonies

in

Magna

Graecia (Southern

Italy and Sicily

),

Asia Minor

and further afield. The emigration

effectively ceased in the 6th century by which time the Greek world had,

culturally and linguistically, become much larger than the area of present-day

Greece. Greek colonies were not politically controlled by their founding cities,

although they often retained religious and commercial links with them.

In this period, huge economic development occurred in Greece and also her

overseas colonies which experienced a growth in commerce and manufacturing.

There was a large improvement in the living standards of the population. Some

studies estimate that the average size of the Greek household, in the period

from 800 BC to 300 BC, increased five times, which indicates a large increase in

the average income of the population.

In the second half of the 6th century, Athens fell under the tyranny of

Peisistratos

and then his sons

Hippias

and

Hipparchos

. However, in 510 BC, at the

instigation of the Athenian aristocrat

Cleisthenes, the Spartan king

Cleomenes I helped the Athenians overthrow the tyranny. Afterwards,

Sparta and Athens promptly turned on each other, at which point Cleomenes I

installed

Isagoras as a pro-Spartan archon. Eager to prevent Athens from

becoming a Spartan puppet, Cleisthenes responded by proposing to his fellow

citizens that Athens undergo a revolution: that all citizens share in political

power, regardless of status: that Athens become a “democracy“.

So enthusiastically did the Athenians take to this idea that, having

overthrown

Isagoras and implemented Cleisthenes’s reforms, they were easily able to

repel a

Spartan-led three-pronged invasion aimed at restoring Isagoras.The

advent of the democracy cured many of the ills of Athens and led to a

‘golden age’ for the Athenians.

Classical Greece

Early Athenian

coin, depicting the head

of Athena

on the obverse and her owl

on the reverse – 5th century BC

Attic Red-figure pottery

,

kylix

by the

Triptolemos Painter

, ca. 480 BC (Paris,

Louvre

)

Delian League (“Athenian Empire”), immediately before the

Peloponnesian War

in 431 BC.

5th century

Athens and Sparta would soon have to become allies in the face of the largest

external threat ancient Greece would see until the Roman conquest. After

suppressing the Ionian Revolt

, a rebellion of the Greek cities

of Ionia,

Darius I of Persia,

King

of Kings of the

Achaemenid Empire, decided to subjugate Greece. His invasion in 490

BC was ended by the Athenian victory at the

Battle of Marathon under

Miltiades the Younger

.

Xerxes I of Persia

, son and successor of Darius

I, attempted his own invasion 10 years later, but despite his larger army he

suffered heavy casualties after the famous rearguard action at

Thermopylae

and victories for the allied Greeks

at the Battles of

Salamis

and

Plataea

. The

Greco-Persian Wars continued until 449 BC, led by the Athenians and

their Delian League

, during which time the

Macedon

,

Thrace,

the

Aegean Islands and Ionia were all liberated from Persian influence.

The dominant position of the maritime Athenian ‘Empire’ threatened Sparta and

the Peloponnesian League

of mainland Greek cities.

Inevitably, this led to conflict, resulting in the

Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). Though effectively a stalemate for

much of the war, Athens suffered a number of setbacks. The

Plague of Athens in 430 BC followed by a disastrous military campaign

known as the Sicilian Expedition

severely weakened Athens.

An estimated one-third of Athenians died, including

Pericles,

their leader.

Sparta was able to foment rebellion amongst Athens’s allies, further reducing

the Athenian ability to wage war. The decisive moment came in 405 BC when Sparta

cut off the grain supply to Athens from the

Hellespont

. Forced to attack, the crippled

Athenian fleet was decisively defeated by the Spartans under the command of

Lysander

at

Aegospotami

. In 404 BC Athens sued for peace,

and Sparta dictated a predictably stern settlement: Athens lost her city walls

(including the Long Walls

), her fleet, and all of her overseas

possessions.

4th century

Greece thus entered the 4th century under a

Spartan hegemony, but it was clear from the start that this was weak.

A demographic crisis meant Sparta was overstretched, and by 395 BC Athens,

Argos, Thebes, and Corinth felt able to challenge Spartan dominance, resulting

in the Corinthian War

(395-387 BC). Another war of

stalemates, it ended with the status quo restored, after the threat of Persian

intervention on behalf of the Spartans.

The Spartan hegemony lasted another 16 years, until, when attempting to

impose their will on the Thebans, the Spartans suffered a decisive defeat at

Leuctra

in 371 BC. The Theban general

Epaminondas then led Theban troops into the Peloponnese, whereupon

other city-states defected from the Spartan cause. The Thebans were thus able to

march into Messenia and free the population.

Deprived of land and its serfs, Sparta declined to a second-rank power. The

Theban hegemony thus established was short-lived; at the

battle of Mantinea

in 362 BC, Thebes lost her

key leader, Epaminondas, and much of her manpower, even though they were

victorious in battle. In fact such were the losses to all the great city-states

at Mantinea that none could establish dominance in the aftermath.

The weakened state of the heartland of Greece coincided with the

Rise of Macedon, led by

Philip II

. In twenty years, Philip had unified

his kingdom, expanded it north and west at the expense of

Illyrian tribes

, and then conquered

Thessaly

and Thrace.

His success stemmed from his innovative reforms to the

Macedon army

. Phillip intervened repeatedly in

the affairs of the southern city-states, culminating in his invasion of 338 BC.

Decisively defeating an allied army of Thebes and Athens at the

Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

, he became de

facto hegemon of all of Greece, except Sparta. He compelled the majority of

the city-states to join the

League of Corinth, allying them to him, and preventing them from

warring with each other. Philip then entered into war against the Achemaenid

Empire but was assassinated by

Pausanias of Orestis

early on in the conflict.

Alexander

, son and successor of Philip,

continued the war. Alexander defeated

Darius III of Persia

and completely destroyed

the Achaemenid Empire, annexing it to Macedon and earning himself the epithet

‘the Great’. When Alexander died in 323 BC, Greek power and influence was at its

zenith. However, there had been a fundamental shift away from the fierce

independence and classical culture of the poleis—and instead towards the

developing

Hellenistic culture

.

Hellenistic Greece

The Hellenistic period

lasted from 323 BC, which

marked the end of the

Wars of Alexander the Great

, to the annexation

of Greece by the Roman Republic

in 146 BC. Although the

establishment of Roman rule did not break the continuity of Hellenistic society

and culture, which remained essentially unchanged until the advent of

Christianity, it did mark the end of Greek political independence.

The major

Hellenistic

realms included the

Diadochi kingdoms

:

Kingdom of

Ptolemy I Soter

Kingdom of

Cassander

Kingdom of

Lysimachus

Kingdom of

Seleucus I Nicator

Epirus

Also shown on the map:

Greek

colonies

Carthage

(non-Greek)

Rome

(non-Greek)

The orange areas were often in dispute after 281 BC. The

kingdom of Pergamon

occupied some

of this area. Not shown:

Indo-Greeks

.

During the Hellenistic period, the importance of “Greece proper” (that is,

the territory of modern Greece) within the Greek-speaking world declined

sharply. The great centers of Hellenistic culture were

Alexandria and Antioch

, capitals of

Ptolemaic Egypt

and

Seleucid Syria

respectively.

The conquests of Alexander had numerous consequences for the Greek

city-states. It greatly widened the horizons of the Greeks and led to a steady

emigration, particularly of the young and ambitious, to the new Greek empires in

the east.[13]

Many Greeks migrated to Alexandria, Antioch and the many other new Hellenistic

cities founded in Alexander’s wake, as far away as what are now

Afghanistan and Pakistan

, where the

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

and the

Indo-Greek Kingdom

survived until the end of

the 1st century BC.

After the death of Alexander his empire was, after quite some conflict,

divided amongst his generals, resulting in the

Ptolemaic Kingdom (based upon

Egypt),

the Seleucid Empire

(based on the

Levant,

Mesopotamia and

Persia

) and the

Antigonid dynasty based in Macedon. In the intervening period, the

poleis of Greece were able to wrest back some of their freedom, although still

nominally subject to the Macedonian Kingdom.

The city-states formed themselves into two leagues; the

Achaean League (including Thebes, Corinth and Argos) and the

Aetolian League (including Sparta and Athens). For much of the period

until the Roman conquest, these leagues were usually at war with each other,

and/or allied to different sides in the conflicts between the Diadochi (the

successor states to Alexander’s empire).

Territories and expansion of the Indo-Greeks.

The Antigonid Kingdom became involved in a war with the Roman Republic in the

late 3rd century. Although the

First Macedonian War

was inconclusive, the

Romans, in typical fashion, continued to make war on Macedon until it was

completely absorbed into the Roman Republic (by 149 BC). In the east the

unwieldy Seleucid Empire gradually disintegrated, although a rump survived until

64 BC, whilst the Ptolemaic Kingdom continued in Egypt until 30 BC, when it too

was conquered by the Romans. The Aetolian league grew wary of Roman involvement

in Greece, and sided with the Seleucids in the

Roman-Syrian War

; when the Romans were

victorious, the league was effectively absorbed into the Republic. Although the

Achaean league outlasted both the Aetolian league and Macedon, it was also soon

defeated and absorbed by the Romans in 146 BC, bringing an end to the

independence of all of Greece.

Roman Greece

The Greek peninsula came under

Roman

rule in 146 BC,

Macedonia

becoming a

Roman province, while southern Greece came under the surveillance of

Macedonia’s praefect. However, some Greek

poleis

managed to maintain a partial

independence and avoid taxation. The

Aegean islands

were added to this territory in

133 BC.

Athens and other Greek cities revolted in 88 BC, and the peninsula

was crushed by the Roman general

Sulla

. The Roman civil wars devastated the land

even further, until

Augustus

organized the peninsula as the

province of

Achaea

in 27 BC.

Greece was a key eastern province of the

Roman

Empire, as the

Roman

culture

had long been in fact

Greco-Roman

. The

Greek language

served as a

lingua franca in the East

and in

Italy,

and many Greek intellectuals such as

Galen

would perform most of their work in Rome

.

|