|

Hadrian

–

Roman Emperor

: 117-138 A.D. –

Hadrian Travels to Egypt

Bronze As 24mm (10.38 grams) Rome mint, circa 134-138 A.D.

Reference: RIC II 839 var. (bust)

HADRIANVS AVG COS III P P, Bare head right.

AEGYPTOS,

Egypt

reclining left, holding sistrum and

resting elbow on basket of grain; at feet, ibis standing right on column

* Numismatic Note: This coin commemorated the travels that

Hadrian made to Egypt touring the provinces of the Roman empire.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

The

ibises (collective

plural ibis; classical plurals ibides and ibes) are a group

of long-legged wading birds

in the family

Threskiornithidae

.

They all have long, down-curved bills, and usually feed as a group, probing

mud for food items, usually

crustaceans

. Most species nest in trees, often

with spoonbills

or

herons

.

The word ibis comes from

Latin

ibis from

Greek

ἶβις ibis from

Egyptian

hb, hīb.

A

sistrum (plural:

sistrums or Latin sistra) is a

musical instrument

of the

percussion

family, chiefly associated with

ancient Egypt

. It consists of a handle and a U-shaped

metal frame, made of brass or bronze and between 76 and 30 cm in width. When

shaken the small rings or loops of thin metal on its movable crossbars produce a

sound that can be from a soft clank to a loud jangling. The name derives from

the Greek

verb σείω, seio, to shake, and

σεῖστρον, seistron, “that which is being shaken.” Its name in the ancient

Egyptian language

was sekhem (sḫm) and

sesheshet (sššt). Sekhem is the simpler, hoop-like sistrum, while

sesheshet (an

onomatopoeic

word) is the

naos

-shaped one.

Publius Aelius Hadrianus

(as emperor Imperator Caesar Divi Traiani filius Traianus Hadrianus Augustus,

and Divus Hadrianus after his

apotheosis

,

known as Hadrian in

English

; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was

emperor

of

Rome

from AD 117 to 138, as well as a

Stoic

and

Epicurean

philosopher. A member of the

gens

Aelia

,

Hadrian was the third of the so-called

Five Good Emperors

.

Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus in

Italica

or, less probably, in Rome

,

from a well-established family which had originated in

Picenum

in

Italy

and had

subsequently settled in

Italica

,

Hispania Baetica

(the republican

Hispania

Ulterior), near the present day location of Seville, Spain. His predecessor

Trajan

was a

maternal cousin of Hadrian’s father.

Trajan never officially designated a successor, but, according to his wife,

Pompeia Plotina

, Trajan named Hadrian emperor immediately before his death.

Trajan’s wife was well-disposed toward Hadrian: Hadrian may well have owed his

succession to her.

Hadrian’s presumed indebtedness to Plotina was widely regarded as the reason

for Hadrian’s succession. However, there is evidence that he accomplished his

succession on his own governing and leadership merits while Trajan was still

alive. For example, between the years AD 100–108 Trajan gave several public

examples of his personal favour towards Hadrian, such as betrothing him to his

grandniece,

Vibia

Sabina

, designating him quaestor Imperatoris, comes Augusti,

giving him Nerva’s diamond “as hope of succession”, proposing him for consul

suffectus, and other gifts and distinctions. The young Hadrian was Trajan’s

only direct male family/marriage/bloodline. The support of Plotina and of

L. Licinius Sura

(died in AD 108) were nonetheless extremely important for

Hadrian, already in this early epoch.

Early

life

Although it was an accepted part of Hadrian’s personal history that Hadrian

was born in Italica

located in the province called

Hispania Baetica

(the southernmost Roman province in the

Iberian Peninsula

, comprising modern

Spain

and

Portugal

),

his biography in

Augustan History

states that he was born in Rome on 24 January 76 of a

family originally Italian,

but Hispanian for many generations. However, this may be a ruse to make Hadrian

look like a person from Rome instead of a person hailing from the provinces.

His father was the Hispano-Roman

Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer

, who as a

senator

of praetorian

rank would spend much of his time in Rome.

Hadrian’s forefathers came from Hadria, modern

Atri

,

an ancient town of Picenum in Italy, but the family had settled in

Italica

in

Hispania Baetica soon after its founding by

Scipio Africanus

. Afer was a paternal cousin of the future Emperor

Trajan

. His

mother was Domitia

Paulina

who

came from Gades (Cádiz).

Paulina was a daughter of a distinguished Hispano-Roman Senatorial family.

Hadrian’s elder sister and only sibling was Aelia Domitia

Paulina

,

married with the triple consul

Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus

, his niece was Julia Serviana

Paulina

and

his great-nephew was Gnaeus Pedanius Fuscus Salinator, from

Barcino

. His

parents died in 86 when Hadrian was ten, and the boy then became a ward of both

Trajan and

Publius Acilius Attianus

(who was later Trajan’s Praetorian Prefect).

Hadrian was schooled in various subjects particular to young

aristocrats

of the day, and was so fond of learning

Greek

literature that he was nicknamed Graeculus (“Greekling”).

Hadrian visited

Italica

when

(or never left it until) he was 14, when he was recalled by Trajan who

thereafter looked after his development. He never returned to Italica although

it was later made a

colonia

in his honour.

His first military service was as a

tribune

of

the

Adiutrix Legio II

. Later, he was to be transferred to the

Minervia Legio I

in

Germany

. When

Nerva

died in 98,

Hadrian rushed to inform Trajan personally. He later became

legate

of a

legion

in Upper Pannonia

and eventually governor of said province. He was also

archon

in

Athens

for a

brief time, and was elected an Athenian citizen.

His career before becoming emperor follows: decemvir stlitibus iudicandis

– sevir turmae equitum Romanorum – praefectus Urbi feriarum Latinarum

– tribunus militum legionis II Adiutricis Piae Fidelis (95, in Pannonia

Inferior) – tribunus militum legionis V Macedonicae (96, in Moesia

Inferior) – tribunus militum legionis XXII Primigeniae Piae Fidelis (97,

in Germania Superior) – quaestor (101) – ab actis senatus –

tribunus plebis (105) – praetor (106) – legatus legionis I

Minerviae Piae Fidelis (106, in Germania Inferior) – legatus Augusti pro

praetore Pannoniae Inferioris (107) – consul suffectus (108) –

septemvir epulonum (before 112) – sodalis Augustalis (before 112) –

archon Athenis (112/13) – legatus Syriae (117).

Hadrian was active in the wars against the

Dacians

(as

legate of the

Macedonica V

) and reputedly won awards from Trajan for his successes.

Due to an absence of military action in his reign, Hadrian’s military skill is

not well attested; however, his keen interest and knowledge of the army and his

demonstrated skill of administration show possible strategic talent.

Hadrian joined Trajan’s expedition against Parthia as a legate on Trajan’s

staff.

Neither during the initial victorious phase, nor during the second phase of the

war when rebellion swept Mesopotamia did Hadrian do anything of note. However

when the governor of

Syria

had to be sent to sort out renewed troubles in Dacia, Hadrian was

appointed as a replacement, giving him an independent command.

Trajan, seriously ill by that time, decided to return to Rome while Hadrian

remained in

Syria

to guard the Roman rear. Trajan only got as far as

Selinus

before he became too ill to go further. While Hadrian may have been

the obvious choice as successor, he had never been adopted as Trajan’s heir. As

Trajan lay dying, nursed by his wife, Plotina (a supporter of Hadrian), he at

last adopted Hadrian as heir. Since the document was signed by Plotina, it has

been suggested that Trajan may have already been dead.

Emperor

Securing

power

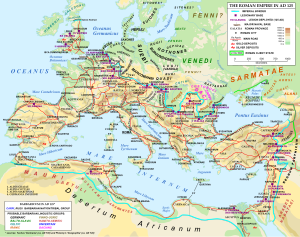

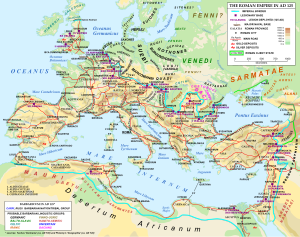

The Roman empire in 125 AD, under the rule of Hadrian.

Castel Sant’Angelo

, the ancient Hadrian

Mausoleum

.

This famous statue of Hadrian in Greek dress was revealed in 2008 to

have been forged in the

Victorian era

by cobbling together a head of Hadrian and an

unknown body. For years the statue had been used by historians as

proof of Hadrian’s love of Hellenic culture.

Hadrian quickly secured the support of the legions — one potential opponent,

Lusius Quietus

, was instantly dismissed.

The Senate’s endorsement followed when possibly falsified papers of adoption

from Trajan were presented (although he had been the ward of

Trajan

). The

rumor of a falsified document of adoption carried little weight — Hadrian’s

legitimacy arose from the endorsement of the Senate and the Syrian armies.

Hadrian did not at first go to Rome — he was busy sorting out the East and

suppressing the Jewish revolt that had broken out under Trajan, then moving on

to sort out the Danube

frontier. Instead, Attianus, Hadrian’s former guardian, was put in

charge in Rome. There he “discovered” a plot involving four leading Senators

including Lusius Quietus and demanded of the Senate their deaths. There was no

question of a trial — they were hunted down and killed out of hand. Because

Hadrian was not in Rome at the time, he was able to claim that Attianus had

acted on his own initiative. According to Elizabeth Speller the real reason for

their deaths was that they were Trajan’s men.

Hadrian

and the military

Despite his own great stature as a military administrator, Hadrian’s reign

was marked by a general lack of major military conflicts, apart from the Second

Roman-Jewish War. He surrendered Trajan’s conquests in

Mesopotamia

, considering them to be indefensible. There was almost a war

with Parthia

around 121, but the threat was averted when Hadrian succeeded in negotiating a

peace.

The peace policy was strengthened by the erection of permanent fortifications

along the empire’s borders (limites,

sl.

limes). The most famous of these is the massive

Hadrian’s Wall

in

Great

Britain

, and the

Danube

and

Rhine

borders

were strengthened with a series of mostly wooden

fortifications

, forts,

outposts

and

watchtowers

, the latter specifically improving communications and local area

security. To maintain morale and keep the troops from getting restive, Hadrian

established intensive drill routines, and personally inspected the armies.

Although his coins showed military images almost as often as peaceful ones,

Hadrian’s policy was peace through strength, even threat.

Cultural

pursuits and patronage

Hadrian has been described, by Ronald Syme among others, as the most

versatile of all the Roman Emperors. He also liked to display a knowledge of all

intellectual and artistic fields. Above all, Hadrian patronized the arts:

Hadrian’s Villa

at Tibur (Tivoli)

was the greatest Roman example of an

Alexandrian

garden, recreating a sacred landscape, lost in large part to the despoliation of

the ruins by the

Cardinal d’Este

who had much of the marble removed to build

Villa

d’Este

. In Rome

,

the Pantheon

, originally built by

Agrippa

but destroyed by fire in 80, was rebuilt under Hadrian in the domed

form it retains to this day. It is among the best preserved of Rome’s ancient

buildings and was highly influential to many of the great architects of the

Italian Renaissance

and

Baroque

periods.

From well before his reign, Hadrian displayed a keen interest in

architecture, but it seems that his eagerness was not always well received. For

example,

Apollodorus of Damascus

, famed architect of the

Forum of Trajan

, dismissed his designs. When

Trajan

,

predecessor to Hadrian, consulted Apollodorus about an architectural problem,

Hadrian interrupted to give advice, to which Apollodorus replied, “Go away and

draw your pumpkins. You know nothing about these problems.” “Pumpkins” refers to

Hadrian’s drawings of domes like the Serapeum in his Villa. It is rumored that

once Hadrian succeeded Trajan to become emperor, he had Apollodorus exiled and

later put to death. It is very possible that this later story was a later

attempt to defame his character, as Hadrian, though popular among a great many

across the empire, was not universally admired, either in his lifetime or

afterward.

Hadrian wrote poetry in both Latin and Greek; one of the few surviving

examples is a Latin poem he reportedly composed on his deathbed (see

below

). He

also wrote an autobiography – not, apparently, a work of great length or

revelation, but designed to scotch various rumours or explain his various

actions. The work is lost but was apparently used by the writer — whether

Marius Maximus

or someone else – on whom the Historia Augusta

principally relied for its vita of Hadrian: at least, a number of

statements in the vita have been identified (by

Ronald

Syme

and others) as probably ultimately stemming from the autobiography.

Hadrian was a passionate hunter, already from the time of his youth according

to one source.

In northwest Asia, he founded and dedicated a city to commemorate a she-bear he

killed.

It is documented that in Egypt he and his beloved

Antinous

killed a lion.

In Rome, eight reliefs featuring Hadrian in different stages of hunting on a

building that began as a monument celebrating a kill.

Another of Hadrian’s contributions to “popular” culture was the beard, which

symbolised his philhellenism. Except for

Nero (also a great

lover of Greek culture), all Roman emperors before Hadrian were clean shaven.

Most of the emperors after Hadrian would be portrayed with beards. Their beards,

however, were not worn out of an appreciation for Greek culture but because the

beard had, thanks to Hadrian, become fashionable. Hadrian had a face covered in

warts and scars, and this may have partially motivated Hadrian’s beard growth.

Hadrian was a

humanist

and deeply

Hellenophile

in all his tastes. He favoured the doctrines of the

philosophers Epictetus

, Heliodorus and

Favorinus

,

but was generally considered an

Epicurean

, as were some of his friends such as

Caius Bruttius Praesens

. At home he attended to social needs. Hadrian

mitigated but did not abolish slavery, had the legal code humanized and forbade

torture. He built libraries,

aqueducts

, baths and theaters. Hadrian is considered by many historians to

have been wise and just: Schiller called him “the Empire’s first servant”, and

British historian

Edward Gibbon

admired his “vast and active genius”, as well as his “equity

and moderation”. In 1776, he stated that Hadrian’s epoch was part of the

“happiest era of human history”.

While visiting Greece in 126, Hadrian attempted to create a kind of

provincial parliament

to bind all the semi-autonomous former city states across all

Greece and Ionia

(in

Asia Minor

). This parliament, known as the

Panhellenion

, failed despite spirited efforts to instill cooperation among

the Hellenes.

Hadrian had a close relationship, widely reported to have been romantic, with

a Greek youth, Antinous

, whom he met in

Bithynia

in

124 when the boy was thirteen or fourteen. While touring

Egypt

in 130, Antinous mysteriously drowned in the

Nile. Deeply

saddened, Hadrian founded the Egyptian city of

Antinopolis

, and had Antinous deified – an unprecedented honour for one not

of the ruling family.

Hadrian died at his villa in

Baiae

. He was

buried in a mausoleum

on the western bank of the

Tiber

, in

Rome, a building

later transformed into a papal fortress,

Castel Sant’Angelo

. The dimensions of his mausoleum, in its original form,

were deliberately designed to be slightly larger than the earlier

Mausoleum of Augustus

.

According to Cassius Dio a gigantic equestrian statue was erected to Hadrian

after his death. “It was so large that the bulkiest man could walk through the

eye of each horse, yet because of the extreme height of the foundation persons

passing along on the ground below believe that the horses themselves as well as

Hadrian are very small.”

Hadrian’s

travels

Purpose

The Stoic-Epicurean Emperor traveled broadly, inspecting and correcting the

legions in the field. Even prior to becoming emperor, he had traveled abroad

with the Roman military, giving him much experience in the matter. More than

half his reign was spent outside of Italy. Other emperors often left Rome to

simply go to war, returning soon after conflicts concluded. A previous emperor,

Nero, once traveled

through Greece and was condemned for his self indulgence. Hadrian, by contrast,

traveled as a fundamental part of his governing, and made this clear to the

Roman senate and the people. He was able to do this because at Rome he possessed

a loyal supporter within the upper echelons of Roman society, a military veteran

by the name of

Marcius Turbo

. Also, there are hints within certain sources that he also

employed a

secret police

force, the

frumentarii

, to exert control and influence in case anything should go wrong

while he journeyed abroad.

Hadrian’s visits were marked by handouts which often contained instructions

for the construction of new public buildings. Hadrian was willful of

strengthening the Empire from within through improved infrastructure, as opposed

to conquering or annexing perceived enemies. This was often the purpose of his

journeys; commissioning new structures, projects and settlements. His almost

evangelical belief in Greek culture strengthened his views: like many emperors

before him, Hadrian’s will was almost always obeyed. His traveling court was

large, including administrators and likely

architects

and

builders

. The burden on the areas he passed through were sometimes great.

While his arrival usually brought some benefits it is possible that those who

had to carry the burden were of different class to those who reaped the

benefits. For example, huge amounts of provisions were requisitioned during his

visit to Egypt

,

this suggests that the burden on the mainly

subsistence farmers

must have been intolerable, causing some measure of

starvation

and hardship.

At the same time, as in later times all the way through the European

Renaissance, kings were welcomed into their cities or lands, and the financial

burden was completely on them, and only indirectly on the poorer class.

Hadrian’s first tour came in 121 and was initially aimed at covering his back

to allow himself the freedom to concern himself with his general cultural aims.

He traveled north, towards

Germania

and inspected the Rhine-Danube frontier, allocating funds to improve the

defenses. However it was a voyage to the Empire’s very frontiers that

represented his perhaps most significant visit; upon hearing of a recent revolt,

he journeyed to Britannia.

Britannia

Hadrian’s Wall

(Vallum Hadriani), a fortification in Northern

England (viewed from

Vercovicium

)

Hadrian’s Gate

, in Antalya, southern Turkey was built to honour

Hadrian who visited the city in 130 CE.

Prior to Hadrian’s arrival on Great Britain there had been a major rebellion

in

Britannia

, spanning roughly two years (119–121).

It was here where in 122 he initiated the building of

Hadrian’s Wall

(the exact Latin name of which is unknown). The purpose of

the wall is academically debated. In 1893,

Haverfield

stated categorically that the Wall was a means of military

defence. This prevailing, early 20th century view was challenged by

Collingwood

[disambiguation

needed] in 1922. Since then, other points of view have been put

forwards; the wall has been seen as a marker to the limits of Romanitas,

as a monument to Hadrian to gain glory in lieu of military campaigns, as work to

keep the Army busy and prevent mutiny and waste through boredom, or to safeguard

the frontier province of Britannia, by preventing future small scale invasions

and unwanted immigration from the northern country of

Caledonia

(now modern day Scotland

). Caledonia was inhabited by tribes known to the Romans as

Caledonians

. Hadrian realized that the Caledonians would refuse to

cohabitate with the Romans. He also was aware that although Caledonia was

valuable, the harsh terrain and highlands made its conquest costly and

unprofitable for the Empire at large. Thus, he decided instead on building a

wall. Unlike the

Germanic limes

, built of wood palisades, the lack of suitable wood in the

area required a stone construction;

nevertheless, the Western third of the wall, from modern-day Carlisle to the

River Irthing, was built of turf because of the lack of suitable building stone.

This problem also led to the narrowing of the width of the wall, from the

original 12 feet to 7, saving masonry.

Hadrian is perhaps most famous for the construction of this wall whose ruins

still span many miles and to date bear his name. In many ways it represents

Hadrian’s will to improve and develop within the

Empire

,

rather than waging wars and conquering.

Under him, a shrine was erected in

York to Britain as

a Goddess, and coins were struck which introduced a female figure as the

personification of Britain, labeled

BRITANNIA

.

By the end of 122 he had concluded his visit to Britannia, and from there headed

south by sea to

Mauretania

.

Parthia

and Anatolia

In 123, he arrived in

Mauretania

where he personally led a campaign against local rebels.

However this visit was to be short, as reports came through that the Eastern

nation of Parthia

was again preparing for war, as a result Hadrian quickly headed eastwards. On

his journey east it is known that at some point he visited

Cyrene

during which he personally made available funds for the training of

the young men of well bred families for the Roman military. This might well have

been a stop off during his journey East. Cyrene had already benefited from his

generosity when he in 119 had provided funds for the rebuilding of public

buildings destroyed in the recent Jewish revolt.

When Hadrian arrived on the

Euphrates

,

he characteristically solved the problem through a negotiated settlement with

the Parthian king

Osroes I

. He then proceeded to check the Roman defenses before setting off

West along the coast of the

Black Sea

.

He probably spent the winter in

Nicomedia

,

the main city of

Bithynia

.

As Nicomedia had been hit by an earthquake only shortly prior to his stay,

Hadrian was generous in providing funds for rebuilding. Thanks to his generosity

he was acclaimed as the chief restorer of the province as a whole. It is more

than possible that Hadrian visited

Claudiopolis

and there espied the beautiful

Antinous

, a

young boy who was destined to become the emperor’s

beloved

. Sources say nothing about when Hadrian met Antinous, however, there

are depictions of Antinous that shows him as a young man of 20 or so. As this

was shortly before Antinous’s drowning in 130 Antinous would more likely have

been a youth of 13 or 14.

It is possible that Antinous may have been sent to Rome to be trained as

page

to serve the emperor and only gradually did he rise to the status of

imperial favorite.

After meeting Antinous, Hadrian traveled through

Anatolia

.

The route he took is uncertain. Various incidents are described such as his

founding of a city within Mysia, Hadrianutherae, after a successful boar hunt.

(The building of the city was probably more than a mere whim — lowly populated

wooded areas such as the location of the new city were already ripe for

development). Some historians dispute whether Hadrian did in fact commission the

city’s construction at all. At about this time, plans to build a temple in Asia

minor were written up. The new temple would be dedicated to Trajan and Hadrian

and built with dazzling white marble.

Greece

Temple of Zeus in Athens.

The

Pantheonn

was rebuilt by Hadrian.

The climax of this tour was the destination that the hellenophile Hadrian

must all along have had in mind, Greece. He arrived in the autumn of 124 in time

to participate in the

Eleusinian Mysteries

. By tradition at one stage in the ceremony the

initiates were supposed to carry arms but this was waived to avoid any risk to

the emperor among them. At the Athenians’ request he conducted a revision of

their constitution — among other things a new

phyle

(tribe) was

added bearing his name.

During the winter he toured the

Peloponnese

. His exact route is uncertain, however

Pausanias

reports of tell-tale signs, such as temples built by Hadrian and

the statue of the emperor built by the grateful citizens of

Epidaurus

in thanks to their “restorer”. He was especially generous to

Mantinea

which supports the theory that Antinous was in fact already

Hadrian’s lover because of the strong link between Mantinea and Antinous’s home

in Bithynia

.

By March 125, Hadrian had reached

Athens

presiding over the festival of

Dionysia

.

The building program that Hadrian initiated was substantial. Various rulers had

done work on building the

Temple of Olympian Zeus

— it was Hadrian who ensured that the job would be

finished. He also initiated the construction of several public buildings on his

own whim and even organized the building of an aqueduct.

Return

to Italy

On his return to Italy, Hadrian made a detour to

Sicily

. Coins

celebrate him as the restorer of the island though there is no record of what he

did to earn this accolade.

Back in Rome he was able to see for himself the completed work of rebuilding

the Pantheon

. Also completed by then was Hadrian’s villa nearby at

Tibur

a pleasant retreat by the

Sabine Hills

for whenever Rome became too much for him. At the beginning of

March 127 Hadrian set off for a tour of Italy. Once again, historians are able

to reconstruct his route by evidence of his hand-outs rather than the historical

records. For instance, in that year he restored the Picentine earth goddess

Cupra

in the town

of

Cupra Maritima

. At some unspecified time he improved the drainage of the

Fucine lake

. Less welcome than such largesse was his decision to divide

Italy into 4 regions under imperial legates with consular rank. Being

effectively reduced to the status of mere provinces did not go down well and

this innovation did not long outlive Hadrian.

Hadrian fell ill around this time, though the nature of his sickness is not

known. Whatever the illness was, it did not stop him from setting off in the

spring of 128 to visit

Africa

. His

arrival began with the good omen of rain ending a

drought

.

Along with his usual role as benefactor and restorer he found time to inspect

the troops and his speech to the troops survives to this day.

Hadrian returned to Italy in the summer of 128 but his stay was brief before

setting off on another tour that would last three years.

Greece,

Asia and Egypt

In September 128 Hadrian again attended the Eleusinian mysteries. This time

his visit to Greece seems to have concentrated on Athens and Sparta — the two

ancient rivals for dominance of Greece. Hadrian had played with the idea of

focusing his Greek revival round

Amphictyonic League

based in Delphi but he by now had decided on something

far grander. His new Panhellenion was going to be a council that would bring

together Greek cities wherever they might be found. The meeting place was to be

the new temple to Zeus in Athens. Having set in motion the preparations —

deciding whose claim to be a Greek city was genuine would in itself take time —

Hadrian set off for

Ephesus

.

In October 130, while Hadrian and his entourage were sailing on the

Nile,

Antinous

drowned, for unknown reasons, though accident, suicide, murder or religious

sacrifice have all been postulated. The emperor was grief stricken. He ordered

Antinous

deified, and cities were named after the boy, medals struck with his effigy, and

statues erected to him in all parts of the empire. Temples were built for his

worship in Bithynia, Mantineia in Arcadia, and Athens, festivals celebrated in

his honour and oracles delivered in his name. The city of

Antinopolis

or Antinoe was founded on the ruins of

Besa

where he died (Cassius Dio, LIX.11; Historia Augusta, Hadrian).

Greece,

Judaea, Illyricum

Hadrian’s movements subsequent to the founding of

Antinopolis

on October 30, 130 are obscure. Whether or not he returned to

Rome, he spent the winter of 131–32 in Athens and probably remained in Greece or

further East because of the Jewish rebellion which broke out in Judaea in 132

(see below). Inscriptions make it clear that he took the field in person against

the rebels with his army in 133; he then returned to Rome, probably in that year

and almost certainly (judging again from inscriptions) via

Illyricum

.

Second

Roman-Jewish War

See also:

Bar Kokhba revolt

In 130, Hadrian visited the ruins of

Jerusalem

,

in Judaea

, left

after the

First Roman-Jewish War

of 66–73. He rebuilt the city, renaming it

Aelia Capitolina

after himself and

Jupiter Capitolinus

, the chief Roman deity. A new temple dedicated to the

worship of

Jupiter

was built on the ruins of the old Jewish

Second Temple

, which had been destroyed in 70.

In addition, Hadrian abolished

circumcision

, which was considered by Romans and Greeks as a form of bodily

mutilation

and hence “barbaric”.

These anti-Jewish policies of Hadrian triggered in Judaea a massive Jewish

uprising, led by

Simon bar Kokhba

and

Akiba ben Joseph

. Following the outbreak of the revolt, Hadrian called his

general

Sextus Julius Severus

from

Britain

, and troops were brought from as far as the

Danube

. Roman

losses were very heavy, and it is believed that an entire legion, the

XXII Deiotariana

was destroyed.[45]

Indeed, Roman losses were so heavy that Hadrian’s report to the

Roman

Senate

omitted the customary salutation “I and the legions are well”.

However, Hadrian’s army eventually put down the rebellion in 135, after three

years of fighting. According to

Cassius

Dio

, during the war 580,000 Jews were killed, 50 fortified towns and 985

villages razed. The final battle took place in

Beitar

, a fortified city 10 km. southwest of Jerusalem. The city only fell

after a lengthy siege, and Hadrian only allowed the Jews to bury their dead

after a period of six days. According to the Babylonian

Talmud

,

after the war Hadrian continued the persecution of Jews. He attempted to root

out Judaism

,

which he saw as the cause of continuous rebellions, prohibited the

Torah

law, the

Hebrew calendar

and executed Judaic scholars (see

Ten

Martyrs

). The sacred scroll was ceremonially burned on the

Temple

Mount

. In an attempt to erase the memory of Judaea, he renamed the province

Syria Palaestina

(after the

Philistines

), and Jews were forbidden from entering its rededicated capital.

When Jewish sources mention Hadrian it is always with the epitaph “may his bones

be crushed” (שחיק עצמות or שחיק טמיא, the Aramaic equivalent),

an expression never used even with respect to

Vespasian

or Titus

who

destroyed the

Second Temple

.

Final

years

Succession

Hadrian spent the final years of his life at Rome. In 134, he took an

Imperial salutation

or the end of the Second Jewish War (which was not actually

concluded until the following year). In 136, he dedicated a new

Temple of Venus and Roma

on the former site of

Nero‘s

Golden House

.

About this time, suffering from poor health, he turned to the problem of the

succession. In 136 he adopted one of the ordinary

consuls

of that year, Lucius Ceionius Commodus, who took the name

Lucius Aelius Caesar

. He was both the stepson and son-in-law of Gaius

Avidius Nigrinus, one of the “four consulars” executed in 118, but was himself

in delicate health. Granted tribunician power and the governorship of

Pannonia

,

Aelius Caesar held a further consulship in 137, but died on January 1, 138.

Following the death of Aelius Caesar, Hadrian next adopted Titus Aurelius

Fulvus Boionius Arrius Antoninus (the future emperor

Antoninus Pius

), who had served as one of the four imperial legates of Italy

(a post created by Hadrian) and as

proconsul

of

Asia

. On 25 February 138 Antoninus received tribunician power and

imperium

.

Moreover, to ensure the future of the dynasty, Hadrian required Antoninus to

adopt both Lucius Ceionius Commodus (son of the deceased Aelius Caesar) and

Marcus Annius Verus (who was the grandson of an influential senator

of the same name

who had been Hadrian’s close friend; Annius was already

betrothed to Aelius Caesar’s daughter Ceionia Fabia). Hadrian’s precise

intentions in this arrangement are debatable. Though the consensus is that he

wanted Annius Verus (who would later become the Emperor

Marcus Aurelius

) to succeed Antoninus, it has also been argued that he

actually intended Ceionius Commodus, the son of his own adopted son, to succeed,

but was constrained to show favour simultaneously to Annius Verus because of his

strong connections to the Hispano-Narbonensian nexus of senatorial families of

which Hadrian himself was a part. It may well not have been Hadrian, but rather

Antoninus Pius — who was Annius Verus’s uncle – who advanced the latter to the

principal position. The fact that Annius would divorce Ceionia Fabia and

re-marry to Antoninus’ daughter Annia Faustina points in the same direction.

When he eventually became Emperor, Marcus Aurelius would co-opt Ceionius

Commodus as his co-Emperor (under the name of

Lucius

Verus

) on his own initiative.

The ancient sources present Hadrian’s last few years as marked by conflict

and unhappiness. The adoption of Aelius Caesar proved unpopular, not least with

Hadrian’s brother-in-law

Lucius Julius Ursus Servianus

and Servianus’ grandson Gnaeus Pedanius Fuscus

Salinator. Servianus, though now far too old, had stood in line of succession at

the beginning of the reign; Fuscus is said to have had designs on the imperial

power for himself, and in 137 he may have attempted a

coup

in which his grandfather was implicated. Whatever the truth, Hadrian ordered

that both be put to death.

Servianus is reported to have prayed before his execution that Hadrian would

“long for death but be unable to die”.

The prayer was fulfilled; as Hadrian suffered from his final, protracted

illness, he had to be prevented from

suicide

on

several occasions.

Death

Hadrian died in 138 on the tenth day of July, in his

villa

at Baiae

at age

62. The cause of death is believed to have been heart failure.

Dio Cassius

and the

Historia Augusta

record details of his failing health, and a study published

in 1980 drew attention to classical sculptures of Hadrian that show he had

diagonal earlobe creases – a characteristic associated with

coronary heart disease

.

Hadrian was buried first at

Puteoli

, near Baiae, on an estate which had once belonged to

Cicero

. Soon

after, his remains were transferred to Rome and buried in the Gardens of Domitia,

close by the almost-complete mausoleum. Upon the completion of the

Tomb of Hadrian

in Rome

in 139 by his successor

Antoninus Pius

, his body was cremated, and his ashes were placed there

together with those of his wife

Vibia

Sabina

and his first adopted son,

Lucius Aelius

, who also died in 138. Antoninus also had him deified in 139

and given a

temple

on the

Campus Martius

.

Poem

by Hadriann

According to the

Historia Augusta

Hadrian composed shortly before his death the following

poem:

-

Animula, vagula, blandula

-

Hospes comesque corporis

-

Quae nunc abibis in loca

-

Pallidula, rigida, nudula,

-

Nec, ut soles, dabis iocos…

-

-

-

P. Aelius Hadrianus Imp.

-

Little soul, roamer and charmerr

-

Body’s guest and companion

-

Into what places will you now depart

-

Pale, stiff, and nude

-

An end to all your jokes…

The sestertius, or sesterce, (pl. sestertii) was an

ancient Roman

coin

. During the

Roman Republic

it was a small,

silver

coin issued only on rare occasions.

During the

Roman Empire

it was a large

brass

coin.

Helmed Roma head right, IIS behind

Dioscuri

riding right, ROMA in linear frame

below. RSC4, C44/7, BMC13.

The name sestertius (originally semis-tertius) means “2 ½”,

the coin’s original value in

asses

, and is a combination of semis

“half” and tertius “third”, that is, “the third half” (0 ½ being

the first half and 1 ½ the second half) or “half the third” (two

units plus half the third unit, or halfway between the second

unit and the third). Parallel constructions exist in

Danish

with halvanden (1 ½),

halvtredje (2 ½) and halvfjerde (3 ½). The form sesterce,

derived from

French

, was once used in preference to the

Latin form, but is now considered old-fashioned.

It is abbreviated as (originally IIS).

Example of a detailed portrait of

Hadrian

117 to 138

History

The sestertius was introduced c. 211 BC as a small

silver

coin valued at one-quarter of a

denarius

(and thus one hundredth of an

aureus

). A silver denarius was supposed to

weigh about 4.5 grams, valued at ten grams, with the silver sestertius

valued at two and one-half grams. In practice, the coins were usually

underweight.

When the denarius was retariffed to sixteen asses (due to the gradual

reduction in the size of bronze denominations), the sestertius was

accordingly revalued to four asses, still equal to one quarter of a

denarius. It was produced sporadically, far less often than the denarius,

through 44 BC.

Hostilian

under

Trajan Decius

250 AD

In or about 23 BC, with the coinage reform of

Augustus

, the denomination of sestertius

was introduced as the large brass denomination. Augustus tariffed the value

of the sestertius as 1/100

Aureus

. The sestertius was produced as the

largest brass

denomination until the late 3rd

century AD. Most were struck in the mint of

Rome

but from AD 64 during the reign of

Nero

(AD 54–68) and

Vespasian

(AD 69–79), the mint of

Lyon

(Lugdunum), supplemented

production. Lyon sestertii can be recognised by a small globe, or legend

stop), beneath the bust.[citation

needed]

The brass sestertius typically weighs in the region of 25 to 28 grammes,

is around 32–34 mm in diameter and about 4 mm thick. The distinction between

bronze

and brass was important to the

Romans. Their name for

brass

was

orichalcum

, a word sometimes also spelled

aurichalcum (echoing the word for a gold coin, aureus), meaning

‘gold-copper’, because of its shiny, gold-like appearance when the coins

were newly struck (see, for example

Pliny the Elder

in his Natural History

Book 34.4).

Orichalcum

was considered, by weight, to be

worth about double that of bronze. This is why the half-sestertius, the

dupondius

, was around the same size and

weight as the bronze as, but was worth two asses.

Sestertii continued to be struck until the late 3rd century, although

there was a marked deterioration in the quality of the metal used and the

striking even though portraiture remained strong. Later emperors

increasingly relied on melting down older sestertii, a process which led to

the zinc component being gradually lost as it burned off in the high

temperatures needed to melt copper (Zinc

melts at 419 °C,

Copper

at 1085 °C). The shortfall was made

up with bronze and even lead. Later sestertii tend to be darker in

appearance as a result and are made from more crudely prepared blanks (see

the Hostilian

coin on this page).

The gradual impact of

inflation

caused by

debasement

of the silver currency meant

that the purchasing power of the sestertius and smaller denominations like

the dupondius and as was steadily reduced. In the 1st century AD, everyday

small change was dominated by the dupondius and as, but in the 2nd century,

as inflation bit, the sestertius became the dominant small change. In the

3rd century silver coinage contained less and less silver, and more and more

copper or bronze. By the 260s and 270s the main unit was the

double-denarius, the

antoninianus

, but by then these small coins

were almost all bronze. Although these coins were theoretically worth eight

sestertii, the average sestertius was worth far more in plain terms of the

metal they contained.

Some of the last sestertii were struck by

Aurelian

(270–275 AD). During the end of

its issue, when sestertii were reduced in size and quality, the

double sestertius

was issued first by

Trajan Decius

(249–251 AD) and later in

large quantity by the ruler of a breakaway regime in the West called

Postumus

(259–268 AD), who often used worn

old sestertii to

overstrike

his image and legends on. The

double sestertius was distinguished from the sestertius by the

radiate crown

worn by the emperor, a device

used to distinguish the dupondius from the as and the antoninianus from the

denarius.

Eventually, the inevitable happened. Many sestertii were withdrawn by the

state and by forgers, to melt down to make the debased antoninianus, which

made inflation worse. In the coinage reforms of the 4th century, the

sestertius played no part and passed into history.

Sestertius of

Hadrian

, dupondius of

Antoninus Pius

, and as of

Marcus Aurelius

As a unit of account

The sestertius was also used as a standard unit of account, represented

on inscriptions with the monogram HS. Large values were recorded in terms of

sestertium milia, thousands of sestertii, with the milia often

omitted and implied. The hyper-wealthy general and politician of the late

Roman Republic,

Crassus

(who fought in the war to defeat

Spartacus

), was said by Pliny the Elder to

have had ‘estates worth 200 million sesterces’.

A loaf of bread cost roughly half a sestertius, and a

sextarius

(~0.5 liter) of

wine

anywhere from less than half to more

than 1 sestertius. One

modius

(6.67 kg) of

wheat

in 79 AD

Pompeii

cost 7 sestertii, of

rye

3 sestertii, a bucket 2 sestertii, a

tunic 15 sestertii, a donkey 500 sestertii.

Records from

Pompeii

show a

slave

being sold at auction for 6,252

sestertii. A writing tablet from

Londinium

(Roman

London

), dated to c. 75–125 AD, records the

sale of a Gallic

slave girl called Fortunata for 600

denarii, equal to 2,400 sestertii, to a man called Vegetus. It is difficult

to make any comparisons with modern coinage or prices, but for most of the

1st century AD the ordinary

legionary

was paid 900 sestertii per annum,

rising to 1,200 under

Domitian

(81-96 AD), the equivalent of 3.3

sestertii per day. Half of this was deducted for living costs, leaving the

soldier (if he was lucky enough actually to get paid) with about 1.65

sestertii per day.

Perhaps a more useful comparison is a modern salary: in 2010 a private

soldier in the US Army (grade E-2) earned about $20,000 a year.

Numismatic value

A sestertius of

Nero

, struck at

Rome

in 64 AD. The reverse

depicts the emperor on horseback with a companion. The legend

reads DECVRSIO, ‘a military exercise’. Diameter 35mm

Sestertii are highly valued by

numismatists

, since their large size gave

caelatores (engravers) a large area in which to produce detailed

portraits and reverse types. The most celebrated are those produced for

Nero

(54-68 AD) between the years 64 and 68

AD, created by some of the most accomplished coin engravers in history. The

brutally realistic portraits of this emperor, and the elegant reverse

designs, greatly impressed and influenced the artists of the

Renaissance

. The series issued by

Hadrian

(117-138 AD), recording his travels

around the Roman Empire, brilliantly depicts the Empire at its height, and

included the first representation on a coin of the figure of

Britannia

; it was revived by

Charles II

, and was a feature of

United Kingdom

coinage until the

2008 redesign

.

Very high quality examples can sell for over a million

dollars

at auction as of 2008, but the

coins were produced in such colossal abundance that millions survive.

|