|

Byzantine Empire

Anonymous Class A2

Bronze Follis 26mm (9.00 grams)

Struck during the joint-reign of Basil II and Constantine VIII 1025-1028 A.D.

Reference: Sear 1813

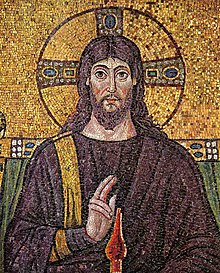

Bust of

Christ

facing, wearing a nimbus crown, pallium and colobium, and holding

book

of Gospels with both hands.

+IhSЧS / XPISTЧS / bASILЄЧ / bASILЄ (“Jesus Christ

King of Kings”) in four

lines.

For more than a century, the production of Follis denomination Byzantine coins

had religious Christian motifs which included included

Jesus Christ, and even Virgin Mary. These coins were designed to honor Christ

and recognize the subservient role of the Byzantine emperor, with many of the

reverse inscriptions translating to “Jesus Christ King of Kings” and “May Jesus

Christ Conquer”. The Follis denomination coins

were the largest bronze denomination coins issued by the Byzantine empire, and

their large size, along with the Christian motif make them a popular coin type

for collectors. This series ran from the period of Byzantine

emperors John I (969-976 A.D.) to Alexius I (1081-1118 A.D.). The accepted

classification was originally devised by Miss Margaret Thompson with her study

of these types of coins. World famous numismatic

author, David R. Sear adopted this classification system for his book entitled,

Byzantine Coins and Their Values. The references about this coin site Mr. Sear’s

book by the number that they appear in that work. The class types of coins

included

Class A1,

Class A2,

Class B,

Class C,

Class D,

Class E,

Class F,

Class G,

Class H,

Class I,

Class J,

Class K. Read more and see examples of these coins by reading the

JESUS CHRIST

Anonymous Class A-N Byzantine Follis Coins Reference.

Click here to see all the Jesus Christ Anonymous Follis coins for sale.

Click here to see all coins bearing Jesus Christ or related available for sale.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

Jesus of Nazareth (c. 5 BC/BCE – c. 30 AD/CE), also

referred to as Jesus Christ or simply Jesus, is the central figure

of

Christianity. Most

Christian denominations

venerate him as

God the

Son

incarnated

and believe that he

rose from the dead

after being

crucified

.

The

principal sources of information regarding Jesus are the four

canonical gospels, and most

critical scholars

find them, at least the

Synoptic Gospels, useful for reconstructing Jesus’ life and

teachings. Some scholars believe apocryphal texts such as the

Gospel of Thomas and the

Gospel according to the Hebrews

are also

relevant

.

Most critical historians agree that Jesus was a

Jew

who was regarded as a teacher and

healer

, that he

was baptized

by

John the Baptist, and

was crucified

in

Jerusalem

on the orders of the

Roman Prefect

Judaea,

Pontius Pilate, on the charge of

sedition

against the Roman Empire

. Critical Biblical scholars and

historians have offered competing descriptions of Jesus as a self-described

Messiah,

as the leader of an apocalyptic movement, as an itinerant sage, as a charismatic

healer, and as the founder of an independent religious movement. Most

contemporary scholars of the

Historical Jesus consider him to have been an independent,

charismatic founder of a Jewish restoration movement, anticipating an imminent

apocalypse. Other prominent scholars, however, contend that Jesus’ “Kingdom

of God” meant radical personal and social transformation instead of a

future apocalypse.

Christians traditionally believe that Jesus was

born of a virgin

:529–32

performed

miracles

,:358–59

founded

the Church

,

rose from the dead

, and

ascended

into

heaven,:616–20

from which he

will return

.:1091–109

Most Christian scholars today present Jesus as the awaited Messiah promised in

the

Old Testament and as God, arguing that he fulfilled many Messianic

prophecies of the Old Testament

. The majority of Christians

worship Jesus as the incarnation of God the Son, one of three divine persons of

a reject Trinitarianism

Trinity, wholly or partly,

believing it to be non-scriptural.

Basil II (Greek:

Βασίλειος Β΄, Basileios II; 958 – 15

December 1025) was a

Byzantine Emperor

from the

Macedonian dynasty

who reigned from 10 January

976 to 15 December 1025. He was known in his time as Basil the

Porphyrogenitus

and Basil the Young

to distinguish him from his supposed ancestor,

Basil I the Macedonian

.

The early years of his long reign were dominated by civil war against

powerful generals from the

Anatolian

aristocracy. Following their

submission, Basil oversaw the stabilization and expansion of the eastern

frontier of the

Byzantine Empire

, and above all, the final and

complete subjugation of

Bulgaria

, the Empire’s foremost European foe,

after a prolonged struggle. For this he was nicknamed by later authors as “the

Bulgar-slayer” (Greek:

Βουλγαροκτόνος, Boulgaroktonos), by

which he is popularly known. At his death, the Empire stretched from Southern

Italy to the Caucasus and from the Danube to the borders of Palestine, its

greatest territorial extent since the

Muslim conquests

four centuries earlier.

Despite near-constant warfare, Basil also showed himself a capable

administrator, reducing the power of the

great land-owning families

who dominated the

Empire’s administration and military, while filling the Empire’s treasury. Of

far-reaching importance was Basil’s decision to offer the hand of his sister

Anna to

Vladimir I of Kiev

[1]

in exchange for military support, which led to the

Christianization

of the

Kievan Rus’

and the incorporation of Russia

within Byzantine cultural sphere.

Birth and childhood

Basil was the son of Emperor

Romanos II

and Empress

Theophano

, whose maternal family was of

Laconian

Greek

origin[2][3][4][5][6][7]

from the Peloponnesian

region of

Laconia

,[8]

possibly from the city of

Sparta

.[9]

His paternal ancestry is of uncertain origins, his putative ancestor Basil I,

the founder of the dynasty, being variously attributed as Armenian, Slavic, or

Greek. Indeed the biological father of

Leo VI the Wise

(Basil IIs great-grandfather)

was possibly not Basil I, but

Michael III

.[10]

The family of Michael III were Anatolians from Phrygia and of Greek speech and

culture, though originally of the

Melchisedechian

heretical faith. In 960, Basil

was associated on the throne by his father, who then died in 963 when Basil was

only five years old. Because he and his brother, the future Emperor

Constantine VIII

(ruled 1025–1028), were too

young to reign in their own right, Basil’s mother

Theophano

married one of Romanos’ leading

generals, who took the throne as the Emperor

Nikephoros II

Phokas several months later in

963. Nikephoros was murdered in 969 by his nephew

John I Tzimisces

, who then became emperor and

reigned for seven years. When Tzimisces died on 10 January 976, Basil II finally

took the throne as senior emperor.

Asian rebellions and alliance with Rus’

Basil was a brave soldier and a superb horseman, and he would prove himself

as an able general and strong ruler. In the early years of his reign,

administration remained in the hands of the

eunuch

Basil Lekapenos

(an illegitimate son of Emperor

Romanos I

), President of the Senate, a wily and

gifted politician who hoped that the young emperors would be his puppets. Basil

waited and watched without interfering, devoting himself to learning the details

of administrative business and military science.

Even though Nikephoros II Phokas and John I Tzimiskes were brilliant military

commanders, both had proven to be lax administrators. Towards the end of his

reign Tzimiskes had belatedly planned to curb the power of the great landowners,

and his death, coming soon after his speaking out against them, led to rumours

that he had been poisoned by Basil Lekapenos, who had acquired vast estates

illegally and feared an investigation and punishment.

As a result of the failures of his immediate predecessors, Basil II found

himself with a serious problem at the outset of his reign as two members of the

wealthy military elite of

Anatolia

,

Bardas Skleros

and

Bardas Phokas

, had sufficient means to

undertake open rebellion against his authority. The chief motive of these men,

both of whom were experienced generals, was to assume the Imperial position that

Nikephoros II and John I had held, and thus return Basil to the role of impotent

cypher. Basil, showing the penchant for ruthlessness that would become his

trademark, took the field himself and suppressed the rebellions of both Skleros

(979) and Phokas (989) but not without the help of 12,000

Georgians

of

Tornikios

and

David III Kuropalates

of

Tao.

The relationship between the two generals was interesting: Phokas was

instrumental in defeating the rebellion of Skleros, but when Phokas himself

later rebelled, Skleros returned from exile to support his old enemy. When

Phokas dropped dead and fell from his horse in battle, Skleros, who had been

imprisoned by his erstwhile accomplice, assumed the leadership of the rebellion,

before being forced into surrendering to Basil in 989. Skleros was allowed to

live, but he ended his days blind, perhaps through disease, though he may have

been punished by blinding.</ref>

These rebellions had a profound effect on Basil’s outlook and methods of

governance. The historian

Psellus

describes the defeated Bardas Skleros

giving Basil the following advice: “Cut down the governors who become

over-proud. Let no generals on campaign have too many resources. Exhaust them

with unjust exactions, to keep them busied with their own affairs. Admit no

woman to the imperial councils. Be accessible to no one. Share with few your

most intimate plans.”[11]

Basil, it would appear, took this advice to heart.

In order to defeat these dangerous revolts, Basil formed an alliance with

Prince

Vladimir I of Kiev

, who in 988 had captured

Chersonesos

, the main Imperial base in the

Crimea

. Vladimir offered to evacuate

Chersonesos and to supply 6,000 of his soldiers as reinforcements to Basil. In

exchange he demanded to be married to Basil’s younger sister

Anna

(963–1011). At first, Basil hesitated. The

Byzantines viewed all the nations of Northern Europe, be they

Franks

or

Slavs

, as

barbarians

. Anna herself objected to marrying a

barbarian ruler, as such a marriage would have no precedence in imperial annals.

Vladimir had conducted long-running research into different religions,

including sending delegates to various countries. Marriage was not his primary

reason for choosing the Orthodox religion. When Vladimir promised to baptize

himself and to convert his people to Christianity, Basil finally agreed.

Vladimir and Anna were married in the Crimea in 989. The Rus’ recruitments were

instrumental in ending the rebellion, and they were later organized into the

Varangian Guard

. This marriage had important

long-term implications, marking the beginning of the process by which the

Grand Duchy of Moscow

many centuries later

would proclaim itself “The

Third Rome

” and claim the political and

cultural heritage of the Byzantine Empire.

The fall of Basil Lekapenos followed the rebellions. He was accused of

plotting with the rebels and punished with exile and the confiscation of his

enormous property. Seeking to protect the lower and middle classes, Basil II

made ruthless war upon the system of immense estates in Asia Minor, which his

predecessor, Romanos I, had endeavored to check.

Campaigns against the Fatimid Caliphate

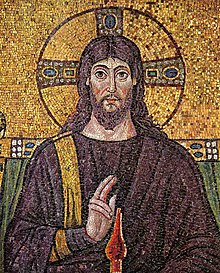

Basil II and

Constantine VIII

, holding cross.

Nomisma histamenon

.

Having put an end to the internal strife, Basil II then turned his attention

to the Empire’s other enemies. The Byzantine civil wars had weakened the

Empire’s position in the east and the gains of Nikephoros II Phokas and John I

Tzimiskes came close to being lost to the

Fatimids

.

In 987/988, a seven-year truce was signed with the Fatimids, stipulating an

exchange of prisoners, the recognition of the Byzantine emperor as protector of

the Christians under Fatimid rule and of the Fatimid Caliph as protector of the

Muslims under Byzantine control, as well as the replacement of the Abbasid

Caliph’s name by that of the Fatimid Caliph in the

Friday prayer

in the mosque of

Constantinople

.[12][13]

Nevertheless, perhaps in the belief that Byzantium would not interfere, in 991

the Fatimids launched a campaign against the

Hamdanid

Emirate of Aleppo

, a Byzantine protectorate.

The Fatimids, under the governor of

Damascus

Manjutakin

, scored a series of successes

against the Hamdanids and their Byzantine allies, including a major victory

against the doux

of

Antioch

,

Michael Bourtzes

, at the

Battle of the Orontes

in September 994. The

latter forced Basil to intervene personally in the East: in a lightning campaign

he rode with his army through

Asia Minor

in sixteen days and reached Aleppo

in April 995, forcing the Fatimid army to retreat without giving battle. The

Byzantines besieged

Tripolis

unsuccessfully and occupied

Tartus

, which they refortified and garrisoned

with Armenian troops. The Fatimid caliph

Al-Aziz

now prepared to take the field in

person against the Byzantines and initiated large-scale preparations, but they

were cut short upon his death.[14][15][16]

Warfare between the two powers continued, with the Byzantines supporting an

anti-Fatimid uprising in

Tyre

. In 998, the Byzantines under Bourtzes’

successor,

Damian Dalassenos

, launched an attack on

Apamea

, but the Fatimid general Jaush ibn al-Samsama

defeated them in battle on 19 July 998. This new defeat brought Basil II once

again to Syria in October 999. Basil spent three months in Syria, during which

the Byzantines raided as far as

Baalbek

, took and garrisoned

Shaizar

and captured three minor forts in its

vicinity (Abu Qubais, Masyath, ‘Arqah), and sacked

Rafaniya

.

Hims

was not seriously threatened, but a

month-long siege of Tripoli in December failed. However, as Basil’s attention

was diverted to developments in

Armenia

, he departed for

Cilicia

in January and dispatched another

embassy to Cairo. In 1000 a ten-year truce was concluded between the two states.[17][18]

For the remainder of the reign of

al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah

(r. 996–1021) relations

remained peaceful, as Hakim was more interested in internal affairs. Even the

acknowledgement of Fatimid suzerainty by

Lu’lu’

of Aleppo in 1004 and the Fatimid-sponsored

instalment of

Fatik Aziz al-Dawla

as the city’s emir in 1017

did not lead to a resumption of hostilities, especially since Lu’lu’ continued

to pay tribute to Byzantium and Fatik quickly began acting as an independent

ruler.[19][20]

Nevertheless, Hakim’s persecution of Christians in his realm, and especially the

destruction of the

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

at his orders in

1009, strained relations and would, along with Fatimid interference in Aleppo,

provide the main focus of Fatimid-Byzantine diplomatic relations until the late

1030s.[21]

Byzantine

conquest of Bulgaria

Basil II and his step-father, Emperor Nikephoros II

Basil also wanted to restore to the Empire territories that it had long lost.

At the start of the second millennium, he took on his greatest adversary,

Samuel of Bulgaria

.

Bulgaria

had been partly subjugated by John I

Tzimiskes, but parts of the country had remained outside Byzantine control,

under the leadership of Samuel and his brothers.

Since the Bulgars had been raiding Byzantine lands since 976, the Byzantine

government sought to cause dissension amongst them by first allowing the escape

of their captive emperor

Boris II of Bulgaria

.

This having failed, Basil used a respite from his conflict with the nobility

to lead an army of 30,000 men into Bulgaria and besiege Sredets (Sofia)

in 986. Taking losses and worried about the loyalty of some of his governors,

Basil lifted the siege and headed back for

Thrace

but fell into an ambush and suffered a

serious defeat at the

Battle of the Gates of Trajan

.

Basil escaped with the help of his

Varangian Guard

and attempted to make up his

losses by turning Samuel’s brother Aaron against him. Aaron was tempted with

Basil’s offer of his own sister Anna in marriage (the same Anna wed to

Vladimir I of Kiev

, two years later), but the

negotiations failed when Aaron discovered that the bride he was sent was a fake.

By 987 Aaron had been eliminated by Samuel, and Basil was busy fighting both

Skleros and Phokas in Asia Minor. Although the titular emperor

Roman of Bulgaria

was captured in 991, Basil

lost Moesia

to the Bulgarians.

In 992, Basil II concluded a treaty with

Pietro Orseolo II

by the terms that

Venice

‘s custom duties in Constantinople would

be reduced from 30

nomismata

to 17 nomismata in return

for the Venetians agreeing to transport Byzantine troops to southern

Italy

in times of war.[22]

Triumph

of Basil II through the

Forum of Constantine

, from the

Madrid Skylitzes

In the years of Basil’s distraction with internal rebellions and recovering

the military situation on his eastern frontier Samuel had extended his rule from

the Adriatic Sea

to the

Black Sea

, recovering most of the lands which

had been Bulgarian before the invasion of

Svyatoslav I of Kiev

. He also conducted

damaging raids into Byzantine territory as far as central

Greece

. The turning of the tide of the conflict

occurred in 996 when the Byzantine general

Nikephoros Ouranos

inflicted a crushing defeat

on a raiding Bulgarian army at a battle on the River

Spercheios

(Sperchius) in Thessaly. Samuel and

his son

Gabriel

were lucky to escape capture.[23]

From 1000, Basil II was free to focus on a war of outright conquest against

Bulgaria, a war he prosecuted with grinding persistence and strategic insight.

In 1000 the Byzantine generals

Nikephoros Xiphias

and Theodorokan took the old

Bulgarian capital of

Great Preslav

, and the towns of Lesser Preslav

and Pliskova.[24]

In 1001 Basil himself, his army operating from Thessalonica, was able to regain

control of Vodena, Verrhoia and Servia.[25]

The following year Basil based his army in

Philippopolis

and occupied the length of the

military road from the western Haemus Mountains to the Danube, thereby cutting

off Samuel’s communications between his Macedonian heartland and Moesia.

Following up this success he laid siege to

Vidin

, which eventually fell following a

prolonged resistance.[26]

Samuel reacted to the Byzantine campaign with a daring stroke; he launched a

large-scale raid into the heart of Byzantine Thrace and surprised the major city

of

Adrianople

.

On returning homeward with his extensive plunder Samuel was intercepted near

the town of

Skopje

by a Byzantine army commanded by the

emperor. Basil’s forces stormed the Bulgarian camp, inflicting a severe defeat

on the Bulgarians and recovering the plunder of Adrianople. Skopje surrendered

shortly after the battle; its governor, Romanos, was treated with overt kindness

by the Emperor.[27]

In 1005, the governor of

Durazzo

, Ashot Taronites, surrendered his city

to the Byzantines. The defection of Durazzo to the Byzantines completed the

isolation of Samuel’s core territories in the highlands of western Macedonia.

Samuel was forced into an almost entirely defensive stance and he extensively

fortified the passes and routes from the Byzantine held coastlands and valleys

into the territory remaining in his possession. During the next few years, the

Byzantine offensive slowed and no significant gains were made, though in 1009 an

attempt by the Bulgarians to counterattack was defeated at the

Battle of Kreta

, which was fought to the east

of Thessalonica.

In 1014 Basil was ready to launch a campaign aimed at destroying Bulgarian

resistance. On 29 July 1014, Basil II and his general Nikephoros Xiphias

outmanoeuvred the Bulgarian army, which was defending one of the fortified

passes, in the

Battle of Kleidion

. Samuel avoided capture only

through the valour of his son Gabriel. Having crushed the Bulgarians, Basil was

said to have captured 15,000 prisoners and blinded 99 of every 100 men, leaving

150 one-eyed men to lead them back to their ruler. Samuel was physically struck

down by the dreadful apparition of his blinded army, and he died two days later

after suffering a stroke. Although the extent of Basil’s mistreatment of the

Bulgarian prisoners may have been exaggerated, this incident helped to give rise

to Basil’s Greek epithet of Boulgaroktonos, meaning “the Bulgar-slayer”,

in later tradition.[28][29]

The first recorded coupling of the term Boulgaroktonos with Basil II

dates from a number of generations after his death, when it is used in a poem

from the reign of

Manuel I Komnenos

dating to around 1166.[30]

Bulgaria fought on for four more years, its resistance fired by Basil’s

cruelty, but it finally submitted in 1018. This submission was the result of

continued military pressure and a successful diplomatic campaign aimed at

dividing and suborning the Bulgarian leadership. This victory over the

Bulgarians, and the later submission of the

Serbs

, fulfilled one of Basil’s goals, as the

Empire regained its ancient

Danubian

frontier for the first time in 400

years. Before returning to

Constantinople

, Basil II celebrated his triumph

in Athens

. Basil showed considerable statesmanship

in his treatment of the defeated Bulgarians; he gave many former Bulgarian

leaders court titles, positions in provincial administration, and high commands

in the army. In this way he sought to absorb the Bulgarian elite into Byzantine

society. Bulgaria did not have a monetary economy to the same extent as was

found in Byzantium, and Basil made the wise decision to accept Bulgarian taxes

in kind. Basil’s successors reversed this policy; a decision which led to

considerable Bulgarian discontent, and rebellion, later in the 11th century.

Khazar campaign

Although the power of the

Khazar

Khaganate

had been broken by the

Kievan Rus’

in the 960s, the Byzantines had not

been able to fully exploit the

power vacuum

and restore their dominion over

the Crimea

and other areas around the

Black Sea

.

In 1016,

Byzantine armies

, in conjunction with

Mstislav of Chernigov

, attacked the Crimea,

much of which had fallen under the sway of the Khazar successor kingdom of

George Tzoul

, based at

Kerch

.

Kedrenos

reports that George Tzoul was captured

and the Khazar

successor-state

was destroyed. Subsequently the

Byzantines occupied the southern Crimea.

Later years

Basil II returned in triumph to Constantinople, then promptly went east and

attacked the

Georgian

Kingdom of

Tao-Klarjeti

, and later secured the annexation

of the sub-kingdoms of

Armenia

(and a promise to have its capital and

surrounding regions to be willed to Byzantium following the death of its king

Hovhannes-Smbat

).[31]

In 1021, he also secured the cession of the

Kingdom of Vaspurakan

by its king,

Seneqerim-John

, in exchange for estates in

Sebasteia

. Basil created in those highlands a

strongly fortified frontier, which, if his successors had been capable, should

have proved an effective barrier against the invasions of the

Seljuk Turks

.

In the meantime, other Byzantine forces restored much of

Southern Italy

, lost over the previous 150

years, to the Empire’s control. Just before Basil died, on 15 December 1025, he

was preparing a military expedition to recover the island of

Sicily

.

Basil was to be buried in the last sarcophagus available in the rotunda of

Constantine I

in the Church of the Holy

Apostles. However, he later asked his brother and successor

Constantine VIII

to be buried in the Church of

St. John the Theologian (i.e. the Evangelist), at the

Hebdomon

Palace complex, outside the walls of

Constantinople. The

epitaph on the tomb

celebrated Basil’s

campaigns and victories. During the pillage of 1204, Basil’s grave was

desecrated by the invading Crusaders of the

Fourth Crusade

.

Assessment

The Byzantine Empire at the death of Basil II in 1025

Basil was a stocky man of less than average stature who, nevertheless, cut a

majestic figure on horseback. He had light blue eyes and strongly arched

eyebrows; in later life his beard became scant but his sidewhiskers were

luxuriant and he had a habit of rolling his whiskers between his fingers when

deep in thought or angry. He was not a fluent speaker and had a loud laugh which

convulsed his whole frame.[32]

As a mature man he had ascetic tastes, and cared little for the pomp and

ceremony of the Imperial court, and typically held court dressed in military

regalia. Still, he was a capable administrator, who, uniquely among the

soldier-emperors, left a full treasury upon his death.[33]

Basil despised literary culture and affected an utter scorn for the learned

classes of Byzantium; however, numerous orators and philosophers were active

during his reign.[34]

He was worshipped by his army, as he spent most of his reign campaigning with

them instead of sending orders from the distant palaces of Constantinople, as

had most of his predecessors. He lived the life of a soldier to the point of

eating the same daily rations as any other member of the army. He also took the

children of deceased officers of his army under his protection, and offered them

shelter, food and education. Many of them later became his soldiers and

officers, and came to think of him as a father.

Besides being called the “Father of the Army”, he was also popular with

country farmers. This class produced most of his army’s supplies and soldiers.

To assure that this continued, Basil’s laws protected small agrarian property

and lowered their taxes. His reign was considered an era of relative prosperity

for the class, despite the almost constant wars. On the other hand, Basil

increased the taxes of the nobility and the church and looked to decrease their

power and wealth. Though understandably unpopular with them, neither of them had

the power to effectively oppose the army-supported Emperor.

Basil never married or had children. As a young man he was a womanizer, but

when he became emperor, he chose to devote himself to the duties of state.

Psellus ascribes Basil’s radical change from a dissolute youth to a grim

autocrat to the circumstances of the rebellions of Bardas Skleros and Bardas

Phokas.[35]

Unfortunately, Basil’s asceticism meant that he was succeeded by his brother and

his family, who proved to be ineffective rulers. Nevertheless, 50 years of

prosperity and intellectual growth followed because the funds of state were

full, the borders were not in danger from exterior intruders, and the Empire

remained the most powerful political entity of the Middle Ages. Also, under

Basil II, the Byzantine Empire probably had a population of about 18 million

people. By AD 1025, Basil II (with an annual revenue of 7,000,000 nomismata)

was able to amass 14,400,000 nomismata (or 200,000 pounds of gold) for

the Imperial treasury due to his prudent management.

In literature

During the 20th century in

Greece

, interest in the prominent emperor led

to a number of biographies and historical novels about him. Arguably the most

popular is Basil Bulgaroktonus (1964) by historical fiction writer

Kostas Kyriazis

(b. 1920). Written as a sequel

to his previous work Theophano (1963), focusing on Basil’s mother, it

examines Basil’s life from childhood till his death at an advanced age, through

the eyes of three fictional narrators. It has been continuously reprinted since

1964.

For his part, commentator Alexander Kiossev, wrote in “Understanding the

Balkans: “The hero of one nation might be the villain of its neighbour (…) The

Byzantine emperor Basil the Murderer (sic) of Bulgarians, a crucial figure in

the Greek pantheon of heroes, is no less important as a subject of hatred for

our [Bulgarian] national mythology “[1].

Penelope Delta

‘s second novel, Ton Kairo tou

Voulgaroktonou (In the Years of the Bulgar-Slayer),[36]

is also set during the reign of Basil II.[37]

It was inspired by correspondence with the historian

Gustave Schlumberger

, a renowned specialist on

the Byzantine Empire, and published in the early years of the 20th Century, a

time when the

Struggle for Macedonia

once again set Greeks

and Bulgarians in bitter enmity with each other.

Ion Dragoumis

, who was Delta’s lover and was

deeply involved in that struggle, in 1907 published the book Martyron kai

Iroon Aima (Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Blood), which was full of resentment

towards everything Bulgarian. He urges Greeks to follow the example of Basil II:

“(…)Instead of blinding so many people,

Basil

should have better killed them instead.

On one hand these people would not suffer as eyeless survivors, on the other the

sheer number of Bulgarians would have diminished by 15 000, which is something

very useful.” Later in the same book, Dragoumis foresaw the appearance of “new

Basils” who would “cross the entire country and will look for Bulgarians in

mountains, caves, villages and forests and will make them flee in refuge or kill

them”.

Rosemary Sutcliff

‘s 1976 historical fiction

novel

Blood Feud

depicts Basil II from the point

of view of a member of his recently created

Varangian Guard

.

Constantine VIII (Greek:

Κωνσταντίνος Η΄, Kōnstantinos VIII)

(960 – 11 November 1028) was reigning

Byzantine Emperor

from 15 December 1025 until

his death. He was the son of the Emperor

Romanos II

and

Theophano

, and the younger brother of the

eminent Basil II

, who died childless and thus left the

rule of the

Byzantine Empire

in his hands.

Family

As a youth, Constantine VIII had been engaged to a daughter of Emperor

Boris II of Bulgaria

, but in the end he married

a Byzantine aristocrat named Helena, daughter of Alypius. By her he had three

daughters: Eudokia, who became a nun, Zoe, future empress, and Theodora.

Life

Basil II

and Constantine VIII,

holding cross.

Nomisma histamenon

.

Constantine VIII had been crowned with his brother by their father from 962;

he was then only an infant. However, for some 63 out of the 68 years of his life

he was eclipsed by other emperors, including

Nikephoros II Phokas

,

John I Tzimiskes

, and Basil II. Even when his

elder brother became senior emperor, Constantine was perfectly content to enjoy

all the privileges of Imperial status without concerning himself with state

affairs. On occasion Constantine participated in his brother’s campaigns against

rebel nobles. In 989, he acted as mediator between Basil II and

Bardas Skleros

. Otherwise he spent his life in

the search of pleasure and entertainment, including spectator sports at the

Hippodrome of Constantinople

, or amusing

himself with riding and hunting.

When Basil II died on 15 December 1025, Constantine finally became sole

emperor, although he ruled for less than three years before his own death on 11

November 1028.

Physically Constantine was tall and graceful, where Basil had been short and

stocky. He was a superb horseman. By the time he became emperor, he had chronic

gout and could hardly walk. His reign was a disaster because he lacked courage

and political savvy. He reacted to every challenge with impulsive cruelty,

persecuting uppity nobles and allegedly ordering the execution or mutilation of

hundreds of innocent men. Constantine carried on as he always had: hunting,

feasting, and enjoying life – and avoided state business as much as possible. He

was poor at appointing officials. Within months, the land laws of Basil II were

dropped under pressure from the

Anatolian

aristocracy (the

dynatoi

), although Constantine struck at

the nobility when threatened by conspiracy.

Like his brother, Constantine died without a male heir. The Empire thus

passed to his daughter

Zoe

, whom he had married to

Romanos Argyros

. Their other daughter, Irene

married Vsevolod I of Kiev and had descendants.

|