|

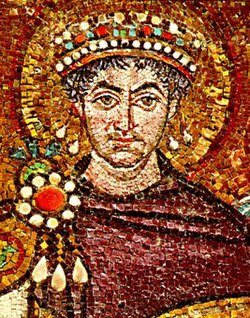

Byzantine Empire

Anonymous Class

C

Bronze Follis 30mm (11.41 grams)

Struck during the reign of

Michael IV

1034-1041 A.D.

Reference: Sear 1825

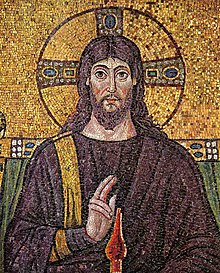

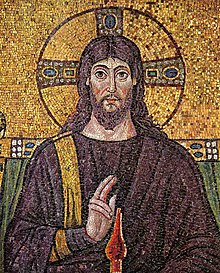

+ЄMMANOVHΛ – Three-quarter length figure of

Christ

Antiphonetes standing facing,

wearing

nimbus crown, pallium and colobium, and raising right hand in

benediction;

in left hand, book

of

Gospels; in field to left, IC; to right, XC.

Jeweled cross

cross

, with pellet at each extremity; in the angles, IC -XC / NI – KA

(“May Jesus Christ Conquer”).

For more than a century, the production of Follis denomination Byzantine coins

had religious Christian motifs which included included

Jesus Christ, and even Virgin Mary. These coins were designed to honor Christ

and recognize the subservient role of the Byzantine emperor, with many of the

reverse inscriptions translating to “Jesus Christ King of Kings” and “May Jesus

Christ Conquer”. The Follis denomination coins

were the largest bronze denomination coins issued by the Byzantine empire, and

their large size, along with the Christian motif make them a popular coin type

for collectors. This series ran from the period of Byzantine

emperors John I (969-976 A.D.) to Alexius I (1081-1118 A.D.). The accepted

classification was originally devised by Miss Margaret Thompson with her study

of these types of coins. World famous numismatic

author, David R. Sear adopted this classification system for his book entitled,

Byzantine Coins and Their Values. The references about this coin site Mr. Sear’s

book by the number that they appear in that work. The class types of coins

included

Class A1,

Class A2,

Class B,

Class C,

Class D,

Class E,

Class F,

Class G,

Class H,

Class I,

Class J,

Class K. Read more and see examples of these coins by reading the

JESUS CHRIST

Anonymous Class A-N Byzantine Follis Coins Reference.

Click here to see all the Jesus Christ Anonymous Follis coins for sale.

Click here to see all coins bearing Jesus Christ or related available for sale.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

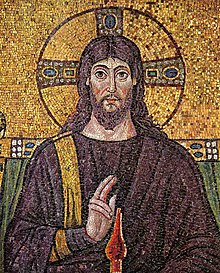

Jesus of Nazareth (c. 5 BC/BCE – c. 30 AD/CE), also

referred to as Jesus Christ or simply Jesus, is the central figure

of

Christianity. Most

Christian denominations

venerate him as

God the

Son

incarnated

and believe that he

rose from the dead

after being

crucified

.

The

principal sources of information regarding Jesus are the four

canonical gospels, and most

critical scholars

find them, at least the

Synoptic Gospels, useful for reconstructing Jesus’ life and

teachings. Some scholars believe apocryphal texts such as the

Gospel of Thomas and the

Gospel according to the Hebrews

are also

relevant

.

Most critical historians agree that Jesus was a

Jew

who was regarded as a teacher and

healer

, that he

was baptized

by

John the Baptist, and

was crucified

in

Jerusalem

on the orders of the

Roman Prefect

Judaea,

Pontius Pilate, on the charge of

sedition

against the Roman Empire

. Critical Biblical scholars and

historians have offered competing descriptions of Jesus as a self-described

Messiah,

as the leader of an apocalyptic movement, as an itinerant sage, as a charismatic

healer, and as the founder of an independent religious movement. Most

contemporary scholars of the

Historical Jesus consider him to have been an independent,

charismatic founder of a Jewish restoration movement, anticipating an imminent

apocalypse. Other prominent scholars, however, contend that Jesus’ “Kingdom

of God” meant radical personal and social transformation instead of a

future apocalypse.

Christians traditionally believe that Jesus was

born of a virgin

:529–32

performed

miracles

,:358–59

founded

the Church

,

rose from the dead

, and

ascended

into

heaven,:616–20

from which he

will return

.:1091–109

Most Christian scholars today present Jesus as the awaited Messiah promised in

the

Old Testament and as God, arguing that he fulfilled many Messianic

prophecies of the Old Testament

. The majority of Christians

worship Jesus as the incarnation of God the Son, one of three divine persons of

a reject Trinitarianism

Trinity, wholly or partly,

believing it to be non-scriptural.

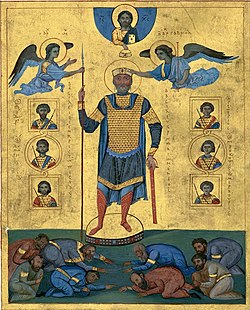

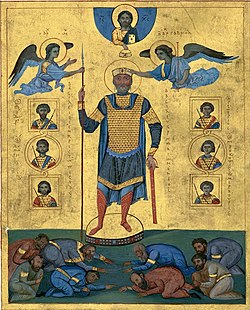

Michael Michael

IV the Paphlagonian (Greek:

Mikhaēl IV Paphlagōn), (1010 – December 10, 1041), was

Eastern Roman Emperor

from April 11, 1034 to December 10, 1041. He owed his

elevation to Empress

Zoe

, daughter of Emperor

Constantine VIII

and wife of

Romanos III

Argyros.

Michael came from a family of

Paphlagonian

peasants, one of whom, the

parakoimomenos

John the Eunuch

had come to preside over the woman’s quarters at the imperial palace. John

brought his younger brothers into the court and there the empress Zoe became

enamoured of Michael, who became her chamberlain. Zoe and Michael decided to use

a slow poison to kill Zoe’s husband Romanos III. However, becoming impatient

with the poison, they drowned him and Zoe immediately married Michael, on April

11, 1034. Michael IV was also proclaimed emperor and reigned together with Zoe

until his death in 1041.

Michael IV was handsome, clever, and generous, but he was uneducated and

suffered from epileptic

fits. Therefore he left the government in the hands of his brother

John, who had already become an influential minister of Constantine VIII and

Romanos III. John’s reforms of the army and financial system revived for a while

the strength of the Empire, which held its own successfully against its foreign

enemies. But the increase in taxation caused discontent among both nobles and

commoners. John’s monopoly of the government led to several failed conspiracies

against him in 1034, 1037, 1038, and 1040 one of which was led by the Empress

Zoe herself. The last conspiracy involved the patrician

Michael Keroularios

, who became a monk to save his life and was later

elected as

patriarch of Constantinople

.

On the eastern frontier the important fortress of

Edessa

was relieved after a prolonged siege. On the western front the

Muslims

were almost driven out of

Sicily

by

George Maniakes

(who campaigned there between 1037 and 1040). Maniakes fell

out with his Lombard allies, however, and lost the support of the Lombards and

Normans. After the recall of Maniakes most of the Sicilian conquests were lost

(1041), and a subsequent expedition against the

Italian

Normans

suffered several defeats.

In the north the Serbs

revolted successfully in 1040, as did the

Bulgarians

in western Bulgaria and

Macedonia

in the same year. This revolt was partly caused by the heavy

taxation in coin imposed on Bulgaria at the time, but it aimed at the

restoration of the Bulgarian state under the leadership of

Peter Delyan

. Although Michael IV was chased out of the vicinity of

Thessalonica

by the rebels, he returned with an army of 40,000 men in 1041

assisted by Norse mercenaries including the future King

Harald III of Norway

. The military success of the Romans was aided by

internal dissention among the Bulgarians and eventually their leaders were

defeated and captured. Michael IV returned to Constantinople in triumph but he

was now decrepit with illness and died on December 10, 1041.

|

Jesus |

Jesus depicted as

the Good

Shepherd

(stained

glass at St

John’s Ashfield) |

| Born |

7–2 BC

Judea, Roman

Empire |

| Died |

30–36 AD

Judea, Roman Empire |

Cause of

death |

Crucifixion |

| Home town |

Nazareth, Galilee |

Jesus (//; Greek: Ἰησοῦς Iesous;

7–2 BC to 30–36 AD), also referred to as Jesus

of Nazareth, is the central figure of Christianity,

whom the teachings of most Christian

denominations hold to be the Son

of God. Christians believe Jesus

to be the awaited Messiah of

the Old

Testament and refer to him as Jesus

Christ or simply Christ, a

name that is also used by non-Christians.

Virtually all modern scholars of antiquity agree that a historical

Jesus existed, although there

is little agreement on the reliability

of the gospel narratives and

their assertions of his divinity. Most

scholars agree that Jesus was a Jewishteacher

from Galilee, was

baptized by John

the Baptist, and was

crucified in Jerusalem on

the orders of the Roman

prefect, Pontius

Pilate. Scholars have constructed

various portraits of the historical

Jesus, which often depict him as having one or more of the following roles:

the leader of an apocalyptic movement,

Messiah, a charismatic healer, a sage and philosopher, or an egalitarian social

reformer. Scholars have

correlated the New

Testament accounts with

non-Christian historical records to arrive at an estimated chronology

of Jesus’ life.

Most Christians believe that Jesus was conceived by the Holy

Spirit, born

of a virgin, performed miracles,

founded the

Church, died by crucifixion as a sacrifice to achieve atonement, rose

from the dead, and ascended into heaven,

from which hewill

return. The majority of

Christians worship Jesus as the incarnation of God

the Son, who is the Second Person of the Holy

Trinity. A few Christian groups reject

Trinitarianism, wholly or partly, as non-scriptural.

In Islam, Jesus (commonly transliterated as Isa)

is considered one of God’s important prophets. To

Muslims, Jesus is a bringer

of scripture and the child of a

virgin birth, but neither divine nor the victim of crucifixion. Judaism rejects the

belief that Jesus was the awaited Messiah, arguing that he did not fulfill the Messianic

prophecies in the Tanakh. Bahá’í scripture

almost never refers to Jesus as the Messiah, but calls him a Manifestation

of God.

Etymology of names

A typical Jew in Jesus’ time had only one name, sometimes supplemented with the

father’s name or the individual’s hometown. Thus,

in the Christian

Bible, Jesus is referred to as “Jesus of Nazareth” (Matthew

26:71), “Joseph’s son” (Luke

4:12), and “Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph” (John

1:45). The name Jesus,

which occurs in a number of languages, is derived from the Latin Iesus,

a transliteration of

the Greek Ἰησοῦς (Iesous). The

Greek form is a rendition of the Aramaic ישוע

(Yeshua), which is derived from the Hebrew יהושע

(Yehoshua). The nameYeshua appears

to have been in use in Judea at the time of the birth of Jesus. The

first-century works of historian Flavius

Josephus refer to at least twenty

different people with this name. The

etymology of Jesus’ name in the context of the New Testament is generally given

as “Yahwehsaves”,

“Yahweh will save”, or “Yahweh is salvation”.

Since early Christianity, Christians have commonly referred to Jesus as “Jesus

Christ”. The word Christ is

derived from the Greek Χριστός (Christos), which

is a translation of the Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ (Masiah),

meaning the “anointed”

and usually transliterated into English as “Messiah”. Christians

designate Jesus as Christ because they believe he is the awaited Messiah prophesied in

the Hebrew

Bible (Old Testament). In

postbiblical usage, Christ became

viewed as a name—one part of “Jesus Christ”—but originally it was a title. Since

the first century, the term “Christian” (meaning “one who owes allegiance to the

person of Christ”) is used to identify the followers of Jesus.

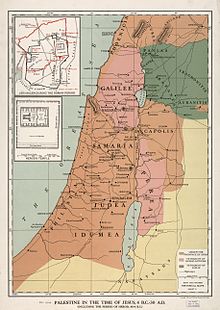

Chronology

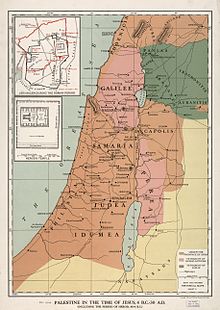

Judea and Galilee at

the time of Jesus

Most scholars agree that Jesus was a Galilean Jew who

was born around the beginning of the first century and died between 30 and 36 AD

in Judea. Amy-Jill

Levine states that the general

scholarly consensus is that Jesus was a contemporary of John

the Baptist and was crucified by

Roman governor Pontius

Pilate, who reigned from 26 to 36 AD. Most

scholars hold that Jesus lived in Galilee and Judea and did not preach or study

elsewhere.

The gospels offer several clues concerning the year of Jesus’ birth. Matthew

2:1 associates the birth of Jesus

with the reign of Herod

the Great, who died around 4 BC, and Luke

1:5 mentions that Herod was on

the throne shortly before the birth of Jesus. Luke’s

gospel also associates the birth with the Census

of Quirinius. Luke

3:23 states that Jesus was “about

thirty years of age” at the start of his ministry, which according to Acts

10:37–38 was preceded by John’s

ministry, which according to Luke

3:1–2 began in the 15th year of

Tiberius’ reign (28 or 29 AD). By

collating the gospel accounts with historical data, along with using various

other methods, most scholars arrive a date of birth between 6 and 4 BC, but

some propose a wider range between 7 and 2 BC.

The years of Jesus’ ministry have been estimated using several different

approaches. One approach applies the

reference in Luke

3:1–2, Acts

10:37–38 and the dates of

Tiberius’ reign, which are well known. This gives a date of around 28–29 AD for

the start of Jesus’ ministry. Another

approach uses the statement about the temple in John

2:13–20, which states that the temple

in Jerusalem was in its 46th year

of construction at the start of Jesus’ ministry, together withJosephus’

statement that the temple’s

reconstruction was started by Herod in the 18th year of his reign, to estimate a

date around 27–29 AD. Another method

uses the date of the death

of John the Baptist and the

marriage of Herod Antipas toHerodias,

based on the writings of Josephus, and correlates it with Matthew

14:4 and Mark

6:18. Given that most scholars

date the marriage of Herod and Herodias as AD 28–35, this yields a date about

28–29 AD.

A number of approaches have been used to estimate the year of the Crucifixion of

Jesus, leading most scholars to agree that he died between 30 and 36 AD. The

gospels state that the event occurred during the prefecture of Pilate, who was

the Roman governor of Judea from 26 AD until 36 AD. Scholars

believe the Crucifixion occurred before the conversion

of Paul, which is estimated at around 33–36 AD. Astronomers

since Isaac

Newton have tried to estimate the

precise date of the Crucifixion, the most widely accepted dates being April 7,

30 AD, and April 3, 33 AD (both Julian).

Life and

teachings in the New Testament

The four canonical

gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke,

and John)

are the main sources for the biography of Jesus, but other parts of the New

Testament, such as the Pauline

epistles, which were probably written decades before the gospels, also

include references to key episodes in his life, such as the Last

Supper in 1

Corinthians 11:23–26. The Acts

of the Apostles (10:37–38 and 19:4)

refers to the early ministry of Jesus and its anticipation by John the Baptist. Acts

1:1–11 says more about the Ascension

of Jesus (also mentioned in 1

Timothy 3:16) than the canonical gospels do.

Canonical gospel

accounts

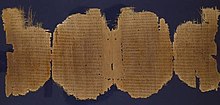

A 3rd-century Greek papyrus of Luke

Not everything contained in the New Testament gospels is considered to be

historically reliable. Elements whose

historical authenticity are disputed include the two accounts of the Nativity,

as well as the Resurrection and certain details about the Crucifixion. Views

on the gospels range from their being inerrant descriptions

of the life of Jesus to their

providing no historical information about his life.

Three of the four canonical gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, are known as the Synoptic

Gospels, from the Greek σύν (syn “together”)

and ὄψις (opsis “view”). According

to the majority viewpoint, the Synoptic Gospels are the primary sources of

historical information about Jesus. They

are very similar in content, narrative arrangement, language and paragraph

structure. Scholars generally agree

that it is impossible to find any direct literary relationship between the

Synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John.

In general, the authors of the New Testament showed little interest in an

absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life with

the secular history of the age. As

stated in John

21:25, the gospels do not claim to provide an exhaustive list of the events

in the life of Jesus. The accounts

were primarily written as theological documents in the context of early

Christianity, with timelines as a secondary consideration. One

manifestation of the gospels as theological documents rather than historical

chronicles is that they devote about one third of their text to just seven days,

namely the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem, referred to as Passion

Week. Although the gospels do not

provide enough details to satisfy the demands of modern historians regarding

exact dates, it is possible to draw from them a general picture of the life

story of Jesus.

The gospel accounts sometimes differ in the ordering of the parables, miracles,

and other events. While the flow of

the some events, such as the Baptism, Transfiguration,

and Crucifixion of

Jesus, and his interactions with the Apostles, are shared among the Synoptic

Gospels, events such as the Transfiguration do not appear in John’s Gospel,

which also differs on other matters, such as the Cleansing

of the Temple. Since the second

century, attempts have been made to harmonize the

gospel accounts into a single narrative, Tatian’s Diatesseron perhaps

being the first.

The gospels include a number of discourses by Jesus on specific occasions, such

as the Sermon

on the Mount and the Farewell

Discourse. They also include over 30 parables spread throughout the

narrative, often with themes that relate to the sermons. John

14:10 stresses the importance of

the words of Jesus and attributes them to the authority of God the Father. The

gospel descriptions of Jesus’ miracles are often accompanied by records of his

teachings.

Genealogy and Nativity

“Adoration of the Shepherds” by Gerard

van Honthorst, 1622

Accounts of the genealogy and

Nativity of Jesus appear in the New Testament only in the gospels of Luke and

Matthew. Outside the New Testament, documents exist that are more or less

contemporary with Jesus and the gospels, but few shed any light on biographical

details of his life, and these two gospel accounts remain the main sources of

information on the genealogy and Nativity.

Matthew begins

his gospel with the genealogy of

Jesus, before giving an account of Jesus’ birth. He traces Jesus’ ancestry to

Abraham through David. Luke

3:22 discusses the genealogy

after describing the Baptism of Jesus, when the voice from Heaven addresses

Jesus and identifies him as the Son

of God. Luke traces Jesus’ ancestry through Adam to

God.

The Nativity is a prominent element in the Gospel of Luke, comprising over 10

percent of the text and being three times as long as Matthew’s Nativity text. Luke’s

account emphasizes events before the birth of Jesus and centers on Mary, while

Matthew’s mostly covers those after the birth and centers on Joseph. Both

accounts state that Jesus was born to Joseph and Mary,

his betrothed,

in Bethlehem,

and both support the doctrine of the virgin

birth, according to which Jesus was miraculously conceived by the Holy

Spirit in Mary’s womb when she was still a virgin.

In Luke

1:31–38 Mary learns from the

angel Gabriel that

she will conceive and bear a child called Jesus through the action of the Holy

Spirit. Following his betrothal to

Mary, Joseph is troubled (Matthew

1:19–20) because Mary is pregnant, but in the first of Joseph’s

three dreams an angel assures him

not be afraid to take Mary as his wife, because her child was conceived by the

Holy Spirit. When Mary is due to give

birth, she and Joseph travel from Nazareth to

Joseph’s ancestral home in Bethlehem to register in the census of Quirinius.

There Mary gives birth to Jesus, and as they have found no room in the inn, she

places the newborn in a manger (Luke

2:1–7). An angel

visits some shepherds and sends

them to adore

the child (Luke

2:22). After presenting Jesus at the Temple, Joseph and Mary return home to

Nazareth. In Matthew

1:1–12, wise

men or Magi from

the East bring gifts to the young Jesus as the King

of the Jews. Herod hears of Jesus’ birth and, wanting him killed, orders the murder

of young male children in Bethlehem. But an angel warns Joseph in his second

dream, and the family flees

to Egypt, later to return and settle in Nazareth.

Early life and

profession

Jesus’ childhood home is identified in the gospels of Luke and Matthew as the

town of Nazareth in Galilee. Mary’s husband Joseph appears in descriptions of

Jesus’ childhood, but no mention is made of him thereafter. The

New Testament books of Matthew, Mark, and Galatians mention

Jesus’ brothers and sisters, but the Greek word adelphos in

these verses has also been translated as “kinsman”, rather than the more usual

“brother”.

Originally written in Koine

Greek, the Gospel of Mark calls Jesus in Mark

6:3 a τέκτων (tekton),

usually understood to mean a carpenter, and Matthew

13:55 says he was the son of a tekton. Although

traditionally translated as “carpenter”, tekton is

a rather general word (from the same root that leads to “technical” and

“technology”) that could cover makers of objects in various materials, even

builders. Beyond the New Testament

accounts, the association of Jesus with woodworking is a constant in the

traditions of the first and second centuries. Justin

Martyr (d. ca. 165) wrote that

Jesus made yokes and ploughs.

Baptism and temptation

Trevisani’s depiction of the typical baptismal scene with the

sky opening and the Holy Spirit descending as a dove, 1723

Gospel accounts of the Baptism of Jesus are always preceded by information about

John the Baptist and his ministry. They

show John preaching penance and repentance for the remission of sins and

encouraging the giving of alms to

the poor (Luke

3:11) as he baptized people in the area of the River

Jordan around Perea at

about the time when Jesus began his ministry. The Gospel of John (1:28)

initially specifies “Bethany beyond the Jordan”, that is Bethabara in

Perea, and later John

3:23 refers to further baptisms

in Ænon “because

there was much water there”.

In the gospels, John had been foretelling (Luke

3:16) the arrival of someone “mightier than I”, and Paul

the Apostle also refers to this (Acts

19:4). In Matthew

3:14, on meeting Jesus, the Baptist says, “I have need to be baptized of

thee”, but Jesus persuades John to baptize him nonetheless. After

he does so and Jesus emerges from the water, the sky opens and a voice from

Heaven states, “This is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew

3:17). The Holy Spirit then descends upon Jesus as a dove. In John

1:29–33, rather than a direct narrative, the Baptist bears witness to the

episode. This is one of two events

described in the gospels where a voice from Heaven calls Jesus “Son”, the other

being the Transfiguration.

After the baptism, the Synoptic Gospels describe the Temptation

of Christ, in which Jesus resisted temptations from the

devil while fasting for forty

days and nights in the Judaean

Desert. The Gospel of John omits

the Temptation and proceeds directly to the first encounter between Jesus and

two of his future disciples (John

1:35–37): on the day after the Baptism, the Baptist sees Jesus again and

calls him the Lamb

of God; two disciples of John the Baptist hear this and follow Jesus.

Ministry

A 19th-century painting depicting the Sermon on the Mount by Carl

Bloch

The gospels present John the Baptist’s ministry as the precursor of that of

Jesus. Starting with his Baptism, Jesus begins his ministry in the countryside

of Judea, near the River Jordan, when he is “about thirty years of age” (Luke

3:23). He then travels, preaches and performs miracles, eventually

completing his ministry with the Last Supper with his disciples in Jerusalem.

Scholars divide the ministry of Jesus into several stages. The Galilean ministry

begins when Jesus returns to Galilee from the Judaean Desert after rebuffing the

temptation of Satan. Jesus preaches around Galilee, and in Matthew

4:18–20, his

first disciples, who will eventually form the core of the early Church,

encounter him and begin to travel with him. This

period includes the Sermon on the Mount, one of Jesus’ major discourses. This

period also includes the Calming

the storm, Feeding

the 5000, Walking

on water, and a number of other miracles and parables. This

period ends with the Confession

of Peter and the Transfiguration.

As Jesus travels towards Jerusalem, in the Perean ministry,

he returns to the area where he was baptized, about one-third the way down from

the Sea of Galilee along the Jordan (John

10:40–42). The final

ministry in Jerusalem begins with

the Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm

Sunday. In the Synoptic Gospels,

during that week Jesus drives the money changers from the Temple and Judas

bargains to betray him. However,

John’s Gospel places the Temple incident during the early part of Jesus’

ministry, and scholars differ on whether these are one or two separate

incidents. This period culminates in

the Last Supper and the Farewell Discourse.

Teachings and preachings

Jesus cleansing a leper –

medieval mosaic from

theMonreale

Cathedral

Commentaries often discuss the teachings of Jesus in terms of his “words and

works”. The words include a number of

sermons, as well as parables that appear throughout the narrative of the

Synoptic Gospels (the Gospel of John includes no narrative parables). The works

include the miracles and other acts performed during Jesus’ ministry. Although

the canonical gospels are the major source of the teachings of Jesus, the

Pauline epistles provide some of the earliest written accounts.

The New Testament presents the teachings of Jesus not merely as his own

preaching, but as divine revelation. John the Baptist, for example, states in John

3:34: “For he whom God hath sent speaketh the words of God: for he giveth

not the Spirit by measure.” In John

7:16 Jesus says, “My teaching is

not mine, but his that sent me.” He asserts the same thing in John

14:10: “Believest thou not that I am in the Father, and the Father in me?

the words that I say unto you I speak not from myself: but the Father abiding in

me doeth his works.” In Matthew

11:27 Jesus claims divine

knowledge, stating: “no one knoweth the Son, save the Father; neither doth any

know the Father, save the Son”.

The Kingdom of God (also called the Kingdom of Heaven in Matthew) is one of the

key elements of Jesus’ teachings in the New Testament. Jesus

promises inclusion in the Kingdom for those who accept his message. He calls

people to repent their sins and to devote themselves completely to God. Jesus

tells his followers to adhere strictly to Jewish

law, although he has broken the law himself, especially regarding the Sabbath. When

asked what the greatest commandment is, Jesus replies: “Thou shalt love the Lord

thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind … And

a second like [unto it] is this, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself” (Matthew

22:37–39). Other ethical teachings of Jesus include loving

one’s enemies, refraining from hatred and lust, and turning

the other cheek (Matthew

5:21–44).

In the gospels, the approximately thirty parables form about one third of Jesus’

recorded teachings. The parables

appear within longer sermons and at other places in the narrative. They

often contain symbolism, and usually relate the physical world to the spiritual. Common

themes in these tales include the kindness and generosity of God and the perils

of transgression. Some of his

parables, such as the Prodigal

Son (Luke

15:11–32), are relatively simple, while others, such as theGrowing

Seed (Mark

4:26–29), are more abstruse.

The gospel episodes that include descriptions of the miracles of Jesus also

often include teachings, and the miracles themselves involve an element of

teaching. Many of the miracles teach

the importance of faith. In the cleansing

of ten lepers and the raising

of Jairus’ daughter, for instance, the beneficiaries are told that their

healing was due to their faith. When

Jesus’ opponents accuse him of performing exorcisms by the power of Beelzebul,

the prince of demons, Jesus counters that he performs miracles by the “Spirit of

God” (Matthew

12:28) or “finger of God” (Luke

11:20).

Proclamation as Christ and Transfiguration

Transfiguration of Jesusdepicting him with Elijah, Mosesand

3 apostles by Carracci,

1594

At about the middle of each of the three Synoptic Gospels, two related episodes

mark a turning point in the narrative: the Confession of Peter and the

Transfiguration of Jesus. They take

place near Caesarea

Philippi, just north of the Sea

of Galilee, at the beginning of the final journey to Jerusalem that

ends in the Passion and Resurrection

of Jesus. These events mark the

beginnings of the gradual disclosure of the identity of Jesus to his disciples

and his prediction of his own suffering and death.

Peter’s Confession begins as a dialogue between Jesus and his disciples in Matthew

16:13, Mark

8:27 and Luke

9:18. Jesus asks his disciples, “who say ye that I am?” Simon Peter answers,

“Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matthew

16:15–16). Jesus replies,

“Blessed art thou, Simon Bar-jonah: for flesh and blood hath not revealed it

unto thee, but my Father who is in heaven.” With this blessing, Jesus affirms

that the titles Peter ascribes to him are divinely revealed, thus unequivocally

declaring himself to be both Christ and the Son of God.

The account of the Transfiguration appears in Matthew

17:1–9, Mark

9:2–8, and Luke

9:28–36. Jesus takes Peter and

two other apostles up an unnamed mountain, where “he was transfigured before

them; and his face did shine as the sun, and his garments became white as the

light.” A bright cloud appears around

them, and a voice from the cloud says, “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am

well pleased; hear ye him” (Matthew

17:1–9). The Transfiguration

reaffirms that Jesus is the Son of God (as in his Baptism), and the command

“hear ye him” identifies him as God’s messenger and mouthpiece.

Final week: betrayal, arrest, trial, and death

The description of the last week of the life of Jesus (often called Passion

Week) occupies about one third of the narrative in the canonical gospels, starting

with a description of the Triumphal

entry into Jerusalem and ending

with his Crucifixion.The last week in Jerusalem is the conclusion of the journey

through Perea and Judea that Jesus began in Galilee. Just

before the entry into Jerusalem, the Gospel of John includes the Raising

of Lazarus, which increases the tension between Jesus and the authorities.

Final entry into

Jerusalem

A painting of Jesus’ final entry into Jerusalem, by Jean-Léon

Gérôme in 1897

In the four canonical gospels, Jesus’ final entry into Jerusalem takes place at

the beginning of the last week of his life, a few days before the Last Supper,

marking the beginning of the Passion narrative. The

day of entry into Jerusalem is identified by Mark and John as Sunday and by

Matthew as Monday; Luke does not identify the day. After

leaving Bethany Jesus

rides a young donkey into Jerusalem. People along the way lay cloaks and small

branches of trees in front of him and sing part of Psalm

118:25–26. The cheering crowds

greeting Jesus as he enters Jerusalem add to the tension between him and the

authorities.

In the three Synoptic Gospels, entry into Jerusalem is followed by the Cleansing

of the Temple, in which Jesus expels the money changers from the temple,

accusing them of turning it into a den of thieves through their commercial

activities. This is the only account of Jesus using physical force in any of the

gospels. John

2:13–16 includes a similar

narrative much earlier, and scholars debate whether the passage refers to the

same episode. The Synoptics include a

number of well-known parables and sermons, such as the Widow’s

mite and the Second

Coming Prophecy, during the week that follows.

The Synoptics record conflicts that took place between Jesus and the Jewish

elders during Passion Week in episodes such as the Authority

of Jesus questioned and the Woes

of the Pharisees, in which Jesus criticizes their hypocrisy.

Judas Iscariot, one of the twelve

apostles, approaches the Jewish elders and strikes a bargain with them, in

which he undertakes to betray Jesus and hand him over to them for a reward of thirty

silver coins.

Last Supper

The Last Supper, depicted in this 16th-century painting by Joan de

Joanes.

The Last Supper is the final meal that Jesus shares with his twelve

apostles in Jerusalem before his

crucifixion. The Last Supper is mentioned in all four canonical gospels, and

Paul’s First

Epistle to the Corinthians (11:23–26)

also refers to it. During the meal, Jesus

predicts that one of his apostles

will betray him. Despite each

Apostle’s assertion that he would not betray him, Jesus reiterates that the

betrayer would be one of those present. Matthew

26:23–25 and John

13:26–27 specifically identify

Judas as the traitor.

In the Synoptics, Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to the disciples,

saying, “This is my body which is given for you”. He then has them all drink

from a cup, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood” (Luke

22:19–20). Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the

bread-and-wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John

6:58–59 (the Bread

of Life Discourse) has a eucharistic character and resonates with the institution

narratives in the Synoptic

Gospels and in the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.

In all four gospels, Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him three

times before the rooster crows

the next morning. In Luke and John,

the prediction is made during the Supper (Luke

22:34, John

22:34). In Matthew and Mark, the prediction is made after the Supper, and

Jesus also predicts that all his disciples will desert him (Matthew

26:31–34, Mark

14:27–30). The Gospel of John

provides the only account of Jesus washing his disciples’ feet before the meal. John

also includes a long sermon by Jesus, preparing his disciples (now without

Judas) for his departure. Chapters

14–17 of the Gospel of John are

known as the Farewell

Discourse and are a significant

source of Christological content.

Agony

in the Garden, betrayal and arrest

A 17th-century depiction of the kiss of Judas and the arrest of

Jesus byCaravaggio

After the Last Supper, Jesus, accompanied by his disciples, takes a walk to

pray. Matthew and Mark identify the place as the garden

of Gethsemane, while Luke identifies it as the Mount of Olives. Judas

appears in the garden, accompanied by a crowd that includes the Jewish priests

and elders and people with weapons. He kisses

Jesus to identify him to the

crowd, which then arrests

Jesus. In an attempt to stop

them, one of Jesus’ disciples uses a sword to cut off the ear a man in the

crowd. Luke states that Jesus

miraculously heals the wound, and John and Matthew report that Jesus criticizes

the violent act, enjoining his disciples not to resist his arrest. In Matthew

26:52 Jesus says, “all

they that take the sword shall perish with the sword”. After

Jesus’ arrest, his disciples go into hiding, and Peter, when questioned, thrice

denies knowing Jesus. After the third

denial, he hears the rooster crow and recalls the prediction as Jesus turns to

look at him. Peter then weeps bitterly.

Trials by the Sanhedrin, Herod and Pilate

Jesus in the upper right hand corner, his hands bound behind, is

being tried at the high priest’s house and turns to look at Peter,

in Rembrandt’s

1660 depiction ofPeter’s

denial.

After his arrest, Jesus is taken to the Sanhedrin,

a Jewish judicial body. The gospel

accounts differ on the details of the trials. In Matthew

26:57, Mark

14:53 and Luke

22:54, Jesus is taken to the high priest’s house, where he is mocked and

beaten that night. Early next morning, the chief priests and scribes lead Jesus

away into their council. John

18:12–14 states that Jesus is

first taken to Annas,

the father-in-law of Caiaphas, and then to Caiaphas. All

four gospels report the Denial

of Peter, where Peter denies knowing Jesus three times before the rooster

crows, as predicted by Jesus.

During the trials Jesus speaks very little, mounts no defense and gives very

infrequent and indirect answers to the questions of the priests, prompting an

officer to slap him. In Matthew

26:62 Jesus’ unresponsiveness

leads the high priest to ask him, “Answerest thou nothing?” In Mark

14:61 the high priest then asks

Jesus, “Art thou the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?”. Jesus replies “I am” and

then predicts the coming of the Son

of Man. This provokes the high

priest to tear his own robe in anger and to accuse Jesus of blasphemy. In

Matthew and Luke, Jesus’ answer is less direct. In Matthew

26:64 he responds “Thou hast

said”, and in Luke

22:70 he says, “Ye say that I

am”.

Taking Jesus to Pilate’s

Court, the Jewish elders ask Roman governor Pontius Pilate to judge and

condemn Jesus, accusing him of claiming to be the King of the Jews. The

use of the word “king” is central to the discussion between Jesus and Pilate. In John

18:36 Jesus states, “My kingdom

is not of this world”, but he does not directly deny being the King of the Jews. In Luke

23:7–15 Pilate realizes that

Jesus is a Galilean, thus coming under the jurisdiction of Herod Antipas. Pilate

sends Jesus to Herod to be tried, but

Jesus says almost nothing in response to Herod’s questions. Herod and his

soldiers mock Jesus, put a gorgeous robe on him to make him look like a king,

and send him back to Pilate. Pilate

then calls together the Jewish elders and says that he has “found no fault in

this man”.

As a Passover custom,

Pilate allows one prisoner chosen by the crowd to be released. He gives the

crowd a choice between Jesus and a murderer called Barabbas. Persuaded by the

elders (Matthew

27:20), the mob chooses to release Barabbas and crucify Jesus. Pilate

writes a sign that reads “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” (abbreviated as INRI in

depictions) to be affixed to the cross of Jesus (John

19:19). He then scourges

Jesus and send him to be

cricified. The soldiers mock Jesus as the King of Jews by clothing him in a

purple robe (which signifies royal status) and placing a Crown

of Thorns on his head. They beat

and taunt him before taking him to Calvary, also

called Golgotha, for crucifixion.

Crucifixion and burial

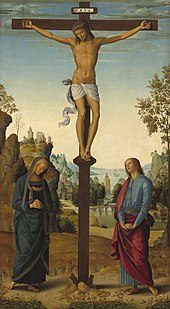

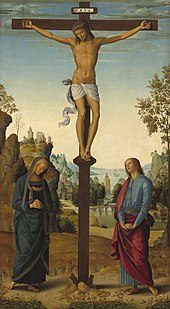

Pietro Perugino’s depiction of the Crucifixion as Stabat

Mater, 1482

Jesus’ crucifixion is described in all four canonical gospels. After the trials,

Jesus makes his way to Calvary by a route known traditionally as the Via

Dolorosa. The three Synoptic Gospels indicate that Simon

of Cyrene assists him, having

been compelled by the Romans to do so. In Luke

23:27–28 Jesus tells the women in

the multitude of people following him not to weep for him but for themselves and

their children. At Calvary Jesus is

offered wine mixed with gall, a concoction usually offered as a painkiller.

Matthew and Mark state that he refuses it.

The soldiers then crucify Jesus and cast lots for his clothes. Above Jesus’ head

on the cross is Pilate’s inscription “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”, and

the soldiers and passers-by mock him about it. Jesus is crucified between two

convicted thieves, one of whom rebukes Jesus, while the other defends him. The

Roman soldiers break the two thieves’ legs (a procedure designed to hasten death

in a crucifixion), but they do not break those of Jesus, as he is already dead.

One soldier, traditionally identified as Saint

Longinus, pierces Jesus’ side with a lance, and water flows out. In Mark

15:39, impressed by the events, the Roman centurion affirms

that Jesus was the Son of God.

On the same day, Joseph

of Arimathea, with Pilate’s permission and with Nicodemus’

help, removes

Jesus’ body from the cross, wraps him in a clean cloth and buries him in a

new rock-hewn

tomb. In Matthew

27:62–66, on the following day the Jews ask Pilate for the tomb to be sealed

with a stone and placed under guard to ensure the body will remain there.

Resurrection and

ascension

New Testament accounts of Jesus’ resurrection state that on the first day of the

week after the crucifixion (typically interpreted as a Sunday), his tomb is

discovered to be empty and his followers encounter him risen from the dead. His

followers arrive at the tomb early in the morning and meet either one or two

beings (men or angels) dressed in bright robes. Mark

16:9 and John

20:15 indicate that Jesus appears

to Mary

Magdalene first, and Luke

16:9 states that she is one of

themyrrhbearers.

Mary Magdalene’s encounter with Jesus after his resurrection,

depicted byAlexander

Andreyevich Ivanov in

1835

After the discovery of the empty tomb, Jesus makes a series of appearances to

the disciples. These include the Doubting

Thomas episode and the appearance

on the road to Emmaus, where Jesus meets two disciples. The catch

of 153 fish is a miracle by the

Sea of Galilee, after which Jesus encourages Peter to serve his followers.

Before he ascends into heaven, Jesus commissions

his disciples to spread his

teachings to all the nations of the world. Luke

24:51 states that Jesus is then

“carried up into heaven”. The Ascension account is elaborated in Acts

1:1–11 and mentioned 1

Timothy 3:16. In Acts, forty days after the Resurrection, as the disciples

look on, “he was taken up; and a cloud received him out of their sight”. 1

Peter 3:22 describes Jesus as

being on “the right hand of God, having gone into heaven”.

The Acts of the Apostles describe several appearances by Jesus after his

Ascension. Acts

7:55 describes a vision

experienced by Stephen just

before his death. On the road to

Damascus, the Apostle Paul is converted to Christianity after seeing a blinding

light and hearing a voice saying, “I am Jesus whom thou persecutest”. In Acts

9:10–18, Ananias

of Damascus is instructed to heal

Paul. It is the last conversation with Jesus reported in the Bible until the Book

of Revelation, in which a

man named John receives a

revelation from Jesus concerning the end

times.

Jesus of Nazareth (c. 5 BC/BCE – c. 30 AD/CE), also

referred to as Jesus Christ or simply Jesus, is the central figure

of

Christianity. Most

Christian denominations

venerate him as

God the

Son

incarnated

and believe that he

rose from the dead

after being

crucified

.

The

principal sources of information regarding Jesus are the four

canonical gospels, and most

critical scholars

find them, at least the

Synoptic Gospels, useful for reconstructing Jesus’ life and

teachings. Some scholars believe apocryphal texts such as the

Gospel of Thomas and the

Gospel according to the Hebrews

are also

relevant

.

The Byzantine Empire was the predominantly

Greek

-speaking continuation of the

Roman Empire

during

Late Antiquity

and the

Middle Ages

. Its capital city was

Constantinople

(modern-day

Istanbul

), originally known as

Byzantium

. Initially the eastern half of the

Roman Empire (often called the Eastern Roman Empire in this context), it

survived the 5th century

fragmentation and collapse

of the

Western Roman Empire

and continued to thrive,

existing for an additional thousand years until it

fell

to the

Ottoman Turks

in 1453. During most of its

existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military

force in Europe. Both “Byzantine Empire” and “Eastern Roman Empire” are

historiographical terms applied in later centuries; its citizens continued to

refer to their empire as the Roman Empire and Romania .

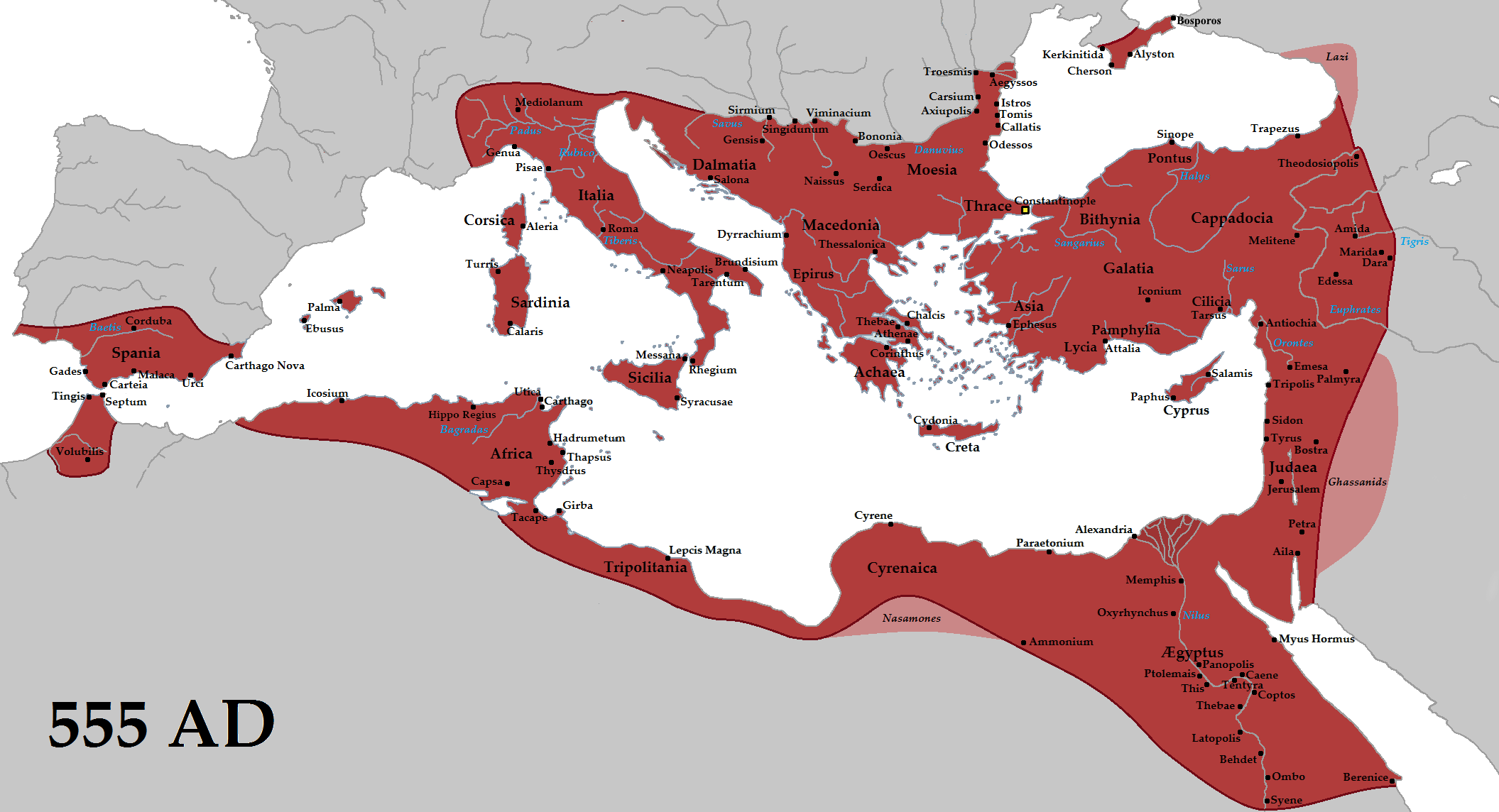

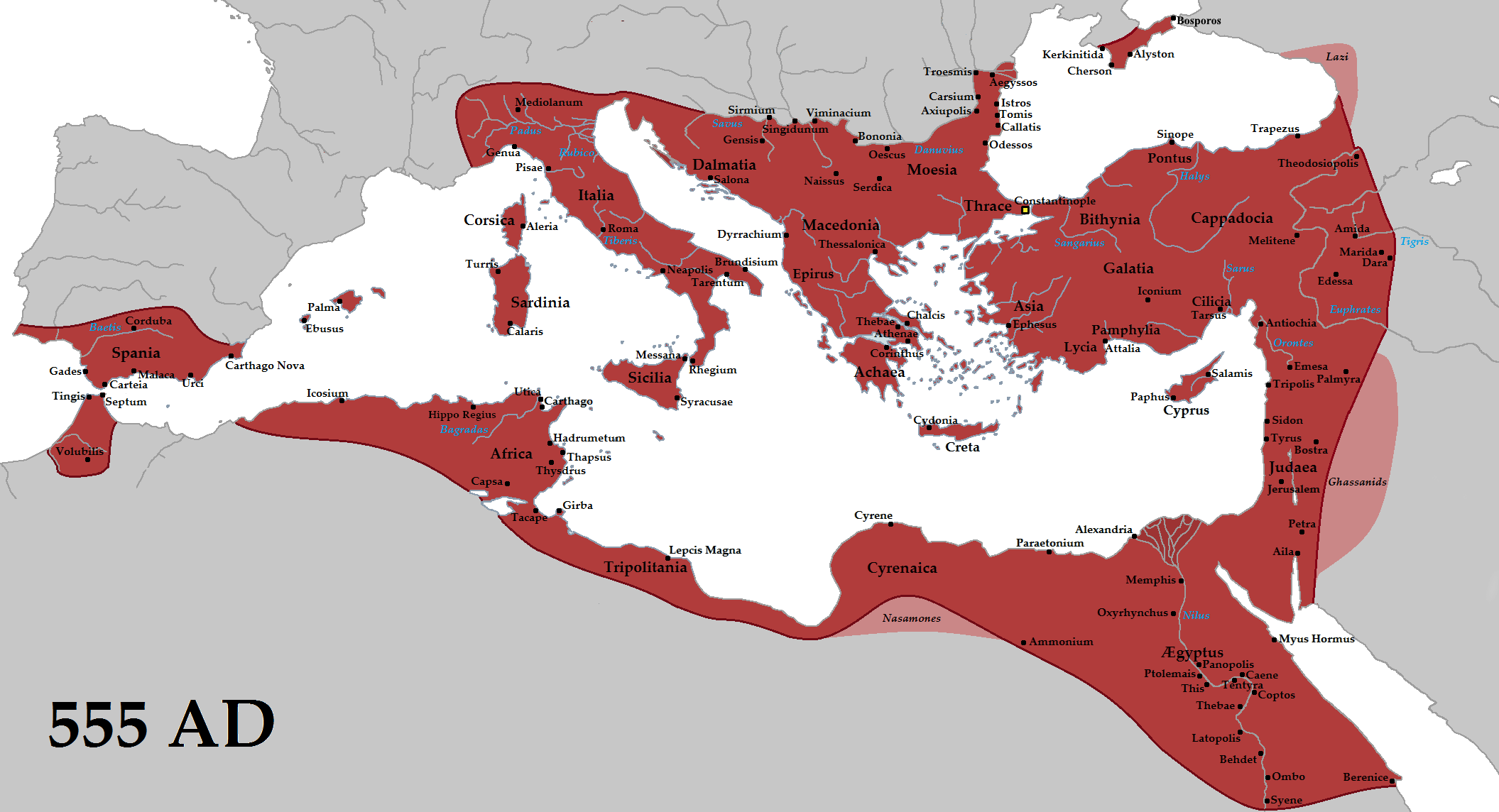

The borders of the Empire evolved a great deal over its existence, as it went

through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of

Justinian I

(r. 527–565), the Empire reached

its greatest extent after reconquering much of the historically Roman western

Mediterranean

coast, including north Africa,

Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries. During the reign

of

Maurice

(r. 582–602), the Empire’s eastern

frontier was expanded and the north stabilised. However, his assassination

caused a

two-decade-long war

with

Sassanid Persia

which exhausted the Empire’s

resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the

Muslim conquests

of the 7th century. During the

Macedonian dynasty

(10th-11th centuries), the

Empire again expanded and experienced a two-century long

renaissance

, which came to an end with the loss

of much of Asia Minor to the

Seljuk Turks

after the

Battle of Manzikert

(1071).

The final centuries of the Empire exhibited a general trend of decline. It

struggled to

recover during the 12th century

, but was

delivered a mortal blow during the

Fourth Crusade

, when Constantinople was sacked

and the Empire

dissolved and divided

into competing Byzantine

Greek and

Latin realms

. Despite the eventual recovery of

Constantinople and

re-establishment of the Empire in 1261

,

Byzantium remained only one of several small rival states in the area for the

final two centuries of its existence. This volatile period led to its

progressive annexation by the Ottomans

over the

15th century and the

Fall of Constantinople

in 1453.

Nomenclature

The first use of the term “Byzantine” to label the later years of the

Roman Empire

was in 1557, when the German

historian

Hieronymus Wolf

published his work Corpus

Historiæ Byzantinæ, a collection of historical sources. The term comes from

“Byzantium”, the name of the city of Constantinople before it became

Constantine’s capital. This older name of the city would rarely be used from

this point onward except in historical or poetic contexts. The publication in

1648 of the Byzantine du Louvre (Corpus

Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae), and in 1680 of

Du Cange

‘s Historia Byzantina further

popularised the use of “Byzantine” among French authors, such as

Montesquieu

. However, it was not until the

mid-19th century that the term came into general use in the Western world. As

regards the English historiography in particular, the first occasion of the

“Byzantine Empire” appears in a 1857 work of

George Finlay

(History of the Byzantine

Empire from 716 to 1057).

The Byzantine Empire was known to its inhabitants as the “Roman Empire”, the

“Empire of the Romans” (Latin: Imperium Romanum, Imperium Romanorum;

Greek: Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων Basileia

tōn Rhōmaiōn, Ἀρχὴ τῶν Ῥωμαίων

Archē tōn Rhōmaiōn), “Romania” (Latin: Romania; Greek:

Ῥωμανία Rhōmania), the “Roman

Republic” (Latin: Res Publica Romana; Greek:

Πολιτεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων Politeia tōn

Rhōmaiōn), Graikia (Greek: Γραικία), and also as Rhōmais

(Greek: Ῥωμαΐς).

Although the Byzantine Empire had a multi-ethnic character during most of its

history and preserved

Romano-Hellenistic

traditions, it became

identified by its western and northern contemporaries with its increasingly

predominant

Greek element

. The occasional use of the term

“Empire of the Greeks” (Latin: Imperium Graecorum) in the West to refer

to the Eastern Roman Empire and of the Byzantine Emperor as Imperator

Graecorum (Emperor of the Greeks) were also used to separate it from the

prestige of the Roman Empire within the new kingdoms of the West.

The authority of the Byzantine emperor as the legitimate Roman emperor was

challenged by the coronation of

Charlemagne

as

Imperator Augustus

by

Pope Leo III

in the year 800. Needing

Charlemagne’s support in his struggle against his enemies in Rome, Leo used the

lack of a male occupant of the throne of the Roman Empire at the time to claim

that it was vacant and that he could therefore crown a new Emperor himself.

Whenever the Popes or the rulers of the West made use of the name Roman

to refer to the Eastern Roman Emperors, they usually preferred the term

Imperator Romaniae (meaning Emperor of Romania) instead of

Imperator Romanorum (meaning Emperor of the Romans), a title that

they applied only to Charlemagne and his successors.

No such distinction existed in the Persian, Islamic, and Slavic worlds, where

the Empire was more straightforwardly seen as the continuation of the Roman

Empire.

Early history

The Baptism of Constantine painted by

Raphael

‘s pupils (1520–1524,

fresco

, Vatican City,

Apostolic Palace

).

Eusebius of Caesarea

records that

(as

was common among converts of early

Christianity

) Constantine delayed receiving

baptism

until shortly before his

death.

The Roman army

succeeded in conquering many

territories covering the entire Mediterranean region and coastal regions in

southwestern Europe

and north Africa. These

territories were home to many different cultural groups, ranging from primitive

to highly sophisticated. Generally speaking, the eastern Mediterranean provinces

were more urbanised than the western, having previously been united under the

Macedonian Empire

and

Hellenised

by the influence of Greek culture.

The west also suffered more heavily from the instability of the 3rd century

AD. This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger

Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries,

leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.

Divisions of

the Roman Empire

In order to maintain control and improve administration, various schemes to

divide the work of the Roman Emperor by sharing it between individuals were

tried between 285 and 324, from 337 to 350, from 364 to 392, and again between

395 and 480. Although the administrative subdivisions varied, they generally

involved a division of labour between East and West. Each division was a form of

power-sharing (or even job-sharing), for the ultimate imperium was not

divisible and therefore the empire remained legally one state—although the

co-emperors often saw each other as rivals or enemies rather than partners.

In 293, emperor

Diocletian

created a new administrative system

(the tetrarchy

), in order to guarantee security in

all endangered regions of his Empire. He associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus),

and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of

Caesar

, to share in their rule and

eventually to succeed the senior partner. The tetrarchy collapsed, however, in

313 and a few years later Constantine I reunited the two administrative

divisions of the Empire as sole Augustus.

Recentralisation

In 330,

Constantine

moved the

seat of the Empire

to

Constantinople

, which he founded as a second

Rome on the site of Byzantium, a city well-positioned astride the trade routes

between East and West. Constantine introduced important changes into the

Empire’s military, monetary, civil and religious institutions. As regards his

economic policies in particular, he has been accused by certain scholars of

“reckless fiscality”, but the gold

solidus

he introduced became a stable currency

that transformed the economy and promoted development.

Under Constantine, Christianity did not become the exclusive religion of the

state, but enjoyed imperial preference, because

the emperor supported it with generous privileges

.

Constantine established the principle that emperors could not settle questions

of doctrine on their own, but should summon instead

general ecclesiastical councils

for that

purpose. His convening of both the

Synod of Arles

and the

First Council of Nicaea

indicated his interest

in the unity of the Church, and showcased his claim to be its head.

In 395,

Theodosius I

bequeathed the imperial office

jointly to his sons:

Arcadius

in the East and

Honorius

in the West, once again dividing

Imperial administration. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, the Eastern part of the

empire was largely spared the difficulties faced by the West—due in part to a

more established urban culture and greater financial resources, which allowed it

to placate invaders with

tribute

and pay foreign mercenaries. This

success allowed

Theodosius II

to focus on the

codification of the Roman law

and the further

fortification of

the walls of Constantinople

, which left the

city impervious to most attacks until 1204.

To fend off the Huns

, Theodosius had to pay an enormous annual

tribute to Attila

. His successor,

Marcian

, refused to continue to pay the

tribute, but Attila had already diverted his attention to the

West

. After his death in 453, the

Hunnic Empire

collapsed, and many of the

remaining Huns were often hired as mercenaries by Constantinople.

Loss of the

western Roman Empire

After the fall of Attila, the Eastern Empire enjoyed a period of peace, while

the Western Empire deteriorated in continuing migration and expansion by

Germanic nations

(its end is usually dated in

476 when the Germanic Roman general

Odoacer

deposed the titular Western Emperor

Romulus Augustulus

). In 480 Emperor

Zeno

abolished the division of the Empire

making himself sole Emperor. Odoacer, now ruler of Italy, was nominally Zeno’s

subordinate but acted with complete autonomy, eventually providing support of a

rebellion against the Emperor.

Zeno negotiated with the invading

Ostrogoths

, who had settled in

Moesia

, convincing the Gothic king

Theodoric

to depart for Italy as magister

militum per Italiam (“commander in chief for Italy”) with the aim to depose

Odoacer. By urging Theodoric into conquering Italy, Zeno rid the Eastern Empire

of an unruly subordinate (Odoacer) and moved another (Theodoric) further from

the heart of the Empire. After Odoacer’s defeat in 493, Theodoric ruled Italy on

his own, although he was never recognised by the eastern emperors as “king” (rex).

In 491,

Anastasius I

, an aged civil officer of Roman

origin, became Emperor, but it was not until 497 that the forces of the new

emperor effectively took the measure of

Isaurian resistance

. Anastasius revealed

himself as an energetic reformer and an able administrator. He perfected

Constantine I’s coinage system by definitively setting the weight of the copper

follis

, the coin used in most everyday

transactions. He also reformed the tax system and permanently abolished the

chrysargyron

tax. The State Treasury contained

the enormous sum of 320,000 lb (150,000 kg) of gold when Anastasius died in 518.

Reconquest of the western provinces

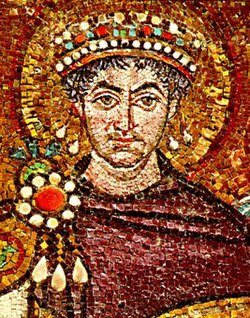

Justinian I

depicted on one of the

famous mosaics of the

Basilica of San Vitale

,

Ravenna

.

Justinian I

, the son of an

Illyrian

peasant, may already have exerted

effective control during the reign of his uncle,

Justin I

(518–527).[32]

He assumed the throne in 527, and oversaw a period of recovery of former

territories. In 532, attempting to secure his eastern frontier, he signed a

peace treaty with

Khosrau I of Persia

agreeing to pay a large

annual tribute to the

Sassanids

. In the same year, he survived a

revolt in Constantinople (the

Nika riots

), which solidified his power but

ended with the deaths of a reported 30,000 to 35,000 rioters on his orders.

In 529, a ten-man commission chaired by

John the Cappadocian

revised the Roman law and

created a new

codification

of laws and jurists’ extracts.

In 534, the Code was updated and, along with the

enactements promulgated by Justinian after 534

,

it formed the system of law used for most of the rest of the Byzantine era.

The western conquests began in 533, as Justinian sent his general

Belisarius

to reclaim the former province of

Africa

from the

Vandals

who had been in control since 429 with

their capital at Carthage. Their success came with surprising ease, but it was

not until 548 that the major local tribes were subdued. In

Ostrogothic Italy

, the deaths of Theodoric, his

nephew and heir

Athalaric

, and his daughter

Amalasuntha

had left her murderer,

Theodahad

(r. 534–536), on the throne despite

his weakened authority.

In 535, a small Byzantine expedition to

Sicily

met with easy success, but the Goths

soon stiffened their resistance, and victory did not come until 540, when

Belisarius captured

Ravenna

, after successful sieges of

Naples

and Rome. In 535–536, Theodahad sent

Pope Agapetus I

to Constantinople to request

the removal of Byzantine forces from Sicily,

Dalmatia

, and Italy. Although Agapetus failed

in his mission to sign a peace with Justinian, he succeeded in having the

Monophysite

Patriarch Anthimus I of Constantinople

denounced, despite empress

Theodora

‘s support and protection.

The Ostrogoths were soon reunited under the command of King

Totila

and

captured Rome

in 546. Belisarius, who had been

sent back to Italy in 544, was eventually recalled to Constantinople in 549. The

arrival of the Armenian eunuch

Narses

in Italy (late 551) with an army of some

35,000 men marked another shift in Gothic fortunes. Totila was defeated at the

Battle of Taginae

and his successor,

Teia, was defeated at the

Battle of Mons Lactarius

(October 552). Despite

continuing resistance from a few Gothic garrisons and two subsequent invasions

by the Franks

and

Alemanni

, the war for the Italian peninsula was

at an end.[40]

In 551, Athanagild

, a noble from

Visigothic

Hispania

, sought Justinian’s help in a

rebellion against the king, and the emperor dispatched a force under

Liberius

, a successful military commander. The

Empire held on to a small slice of the

Iberian Peninsula

coast until the reign of

Heraclius.

In the east, the Roman–Persian Wars continued until 561 when the envoys of

Justinian and Khosrau agreed on a 50-year peace. By the mid-550s, Justinian had

won victories in most theatres of operation, with the notable exception of the

Balkans

, which were subjected to repeated

incursions from the Slavs

and the

Gepids

. Tribes of

Serbs

and

Croats

were later resettled in the northwestern

Balkans, during the reign of Heraclius. Justinian called Belisarius out of

retirement and defeated the new Hunnish threat. The strengthening of the Danube

fleet caused the

Kutrigur

Huns to withdraw and they agreed to a

treaty that allowed safe passage back across the Danube.

During the 6th century, traditional Greco-Roman culture was still influential

in the Eastern empire. Philosophers such as

John Philoponus

drew on

neoplatonic

ideas in addition to Christian

thought and empiricism

. Nevertheless,

Hellenistic philosophy

began to be supplanted

by or amalgamated into newer

Christian philosophy

. Polytheism was

suppressed by the state

. The closure of the

Platonic Academy

was a notable turning point.

Hymns written by

Romanos the Melodist

marked the development of

the Divine Liturgy

, while architects and builders

worked to complete the new Church of the

Holy Wisdom

,

Hagia Sophia

, which was designed to replace an

older church destroyed during the Nika Revolt. The Hagia Sophia stands today as

one of the major monuments of Byzantine architectural history.[45]

During the 6th and 7th centuries, the Empire was struck by a

series of epidemics

, which greatly devastated

the population and contributed to a significant economic decline and a weakening

of the Empire.

After Justinian died in 565, his successor,

Justin II

refused to pay the large tribute to

the Persians. Meanwhile, the Germanic

Lombards

invaded Italy; by the end of the

century only a third of Italy was in Byzantine hands. Justin’s successor,

Tiberius II

, choosing between his enemies,

awarded subsidies to the

Avars

while taking military action against the

Persians. Though Tiberius’ general,

Maurice

, led an effective campaign on the

eastern frontier, subsidies failed to restrain the Avars. They captured the

Balkan fortress of

Sirmium

in 582, while the Slavs began to make

inroads across the Danube.

Maurice, who meanwhile succeeded Tiberius, intervened in a Persian civil war,

placed the legitimate

Khosrau II

back on the throne and married his

daughter to him. Maurice’s treaty with his new brother-in-law enlarged the

territories of the Empire to the East and allowed the energetic Emperor to focus

on the Balkans. By 602, a series of successful Byzantine

campaigns

had pushed the Avars and Slavs back

across the Danube.

Shrinking borders

Heraclian dynasty

After Maurice’s murder by

Phocas

, Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer

the

Roman province of Mesopotamia

. Phocas, an

unpopular ruler invariably described in Byzantine sources as a “tyrant”, was the

target of a number of Senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by

Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople from

Carthage

with an icon affixed to the prow of

his ship.

Following the ascension of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into

Asia Minor, occupying

Damascus

and

Jerusalem

and removing the

True Cross

to

Ctesiphon

. The counter-attack launched by

Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an

acheiropoietos

image of Christ was carried as a

military standard[51]

(similarly, when Constantinople was saved from an Avar siege in 626, the victory

was attributed to the icons of the Virgin that were led in procession by

Patriarch Sergius

about the walls of the city).

The main Sassanid force was destroyed at

Nineveh

in 627, and in 629 Heraclius restored

the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony. The war had exhausted both

the Byzantines and Sassanids, however, and left them extremely vulnerable to the

Muslim forces

that emerged in the following

years. The Byzantines suffered a crushing defeat by the Arabs at the

Battle of Yarmouk

in 636, while Ctesiphon fell

in 634.

Siege of Constantinople (674–678)

The Arabs, now firmly in

control of Syria and the Levant

, sent frequent

raiding parties deep into Asia Minor, and in

674–678 laid siege to Constantinople

itself.

The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of

Greek fire

, and a thirty-years’ truce was

signed between the Empire and the

Umayyad Caliphate

. However, the

Anatolian

raids continued unabated, and

accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with the inhabitants of many

cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the old city walls, or

relocating entirely to nearby fortresses. Constantinople itself dropped

substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just 40,000–70,000, and, like

other urban centres, it was partly ruralised. The city also lost the free grain

shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the Persians and then to the Arabs,

and public wheat distribution ceased.

The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic

institutions was filled by the theme system, which entailed dividing Asia Minor

into “provinces” occupied by distinct armies that assumed civil authority and

answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its

roots in certain ad hoc measures taken by Heraclius, but over the course

of the 7th century it developed into an entirely new system of imperial

governance. The massive cultural and institutional restructuring of the Empire

consequent on the loss of territory in the 7th century has been said to have

caused a decisive break in east Mediterranean Romanness and that the

Byzantine state is subsequently best understood as another successor state

rather than a real continuation of the Roman Empire.

The withdrawal of large numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the

Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual

southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Asia Minor,

many cities shrank to small fortified settlements. In the 670s, the

Bulgars

were pushed south of the Danube by the

arrival of the Khazars

. In 680, Byzantine forces sent to

disperse these new settlements were defeated.

In 681,

Constantine IV

signed a treaty with the Bulgar

khan

Asparukh

, and the

new Bulgarian state

assumed sovereignty over a

number of Slavic tribes that had previously, at least in name, recognised

Byzantine rule. In 687–688, the final Heraclian emperor,

Justinian II

, led an expedition against the

Slavs and Bulgarians, and made significant gains, although the fact that he had

to fight his way from

Thrace

to

Macedonia

demonstrates the degree to which

Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.

Justinian II attempted to break the power of the urban aristocracy through

severe taxation and the appointment of “outsiders” to administrative posts. He

was driven from power in 695, and took shelter first with the Khazars and then

with the Bulgarians. In 705, he returned to Constantinople with the armies of

the Bulgarian

khan

Tervel

, retook the throne, and instituted a

reign of terror against his enemies. With his final overthrow in 711, supported

once more by the urban aristocracy, the Heraclian dynasty came to an end.

Isaurian dynasty to the ascension of Basil I

Leo III the Isaurian

turned back the Muslim

assault in 718 and addressed himself to the task of reorganising and

consolidating the themes in Asia Minor. His successor,

Constantine V

, won noteworthy victories in

northern Syria and thoroughly undermined Bulgarian strength.

Taking advantage of the Empire’s weakness after the

Revolt of Thomas the Slav

in the early 820s,

the Arabs reemerged and

captured Crete

. They also successfully attacked

Sicily, but in 863 general

Petronas

gained a

huge victory

against

Umar al-Aqta

, the

emir of

Melitene

. Under the leadership of emperor

Krum, the Bulgarian threat also reemerged, but in 815–816 Krum’s son,

Omurtag

, signed a

peace treaty

with

Leo V

.

Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)

The accession of

Basil I

to the throne in 867 marks the

beginning of the

Macedonian dynasty

, which would rule for the

next two and a half centuries. This dynasty included some of the most able

emperors in Byzantium’s history, and the period is one of revival and

resurgence. The Empire moved from defending against external enemies to

reconquest of territories formerly lost.

In addition to a reassertion of Byzantine military power and political

authority, the period under the Macedonian dynasty is characterised by a

cultural revival in spheres such as philosophy and the arts. There was a

conscious effort to restore the brilliance of the period before the

Slavic

and subsequent

Arab invasions

, and the Macedonian era has been

dubbed the “Golden Age” of Byzantium. Though the Empire was significantly

smaller than during the reign of Justinian, it had regained significant

strength, as the remaining territories were less geographically dispersed and

more politically, economically, and culturally integrated.

Wars against the Arabs

In the early years of Basil I’s reign, Arab raids on the coasts of Dalmatia

were successfully repelled, and the region once again came under secure

Byzantine control. This enabled Byzantine missionaries to penetrate to the

interior and convert the Serbs and the principalities of modern-day

Herzegovina

and

Montenegro

to Orthodox Christianity. An attempt

to retake

Malta

ended disastrously, however, when the

local population sided with the Arabs and massacred the Byzantine garrison.

By contrast, the Byzantine position in

Southern Italy

was gradually consolidated so

that by 873 Bari

had once again come under Byzantine rule,

and most of Southern Italy would remain in the Empire for the next 200 years. On

the more important eastern front, the Empire rebuilt its defences and went on

the offensive. The

Paulicians

were defeated and their capital of

Tephrike (Divrigi) taken, while the offensive against the

Abbasid Caliphate

began with the recapture of

Samosata

.

Under Michael’s son and successor,

Leo VI the Wise

, the gains in the east against

the now weak Abbasid Caliphate continued. However, Sicily was lost to the Arabs

in 902, and in 904

Thessaloniki

, the Empire’s second city, was

sacked by an Arab fleet. The weakness of the Empire in the naval sphere was

quickly rectified, so that a few years later a Byzantine fleet had re-occupied

Cyprus

, lost in the 7th century, and also

stormed Laodicea

in Syria. Despite this revenge, the

Byzantines were still unable to strike a decisive blow against the Muslims, who

inflicted a crushing defeat on the imperial forces when they attempted to regain

Crete

in 911.

The death of the Bulgarian tsar

Simeon I

in 927 severely weakened the

Bulgarians, allowing the Byzantines to concentrate on the eastern front.

Melitene was permanently recaptured in 934, and in 943 the famous general

John Kourkouas

continued the offensive in

Mesopotamia

with some noteworthy victories,

culminating in the reconquest of

Edessa

. Kourkouas was especially celebrated for

returning to Constantinople the venerated

Mandylion

, a relic purportedly imprinted with a

portrait of Christ.[75]

The soldier-emperors

Nikephoros II Phokas

(reigned 963–969) and

John I Tzimiskes

(969–976) expanded the empire

well into Syria, defeating the emirs of north-west

Iraq. The great city of

Aleppo

was taken by Nikephoros in 962, and the

Arabs were decisively expelled from Crete in 963. The recapture of Crete put an

end to Arab raids in the Aegean, allowing mainland Greece to flourish once

again. Cyprus

was permanently retaken in 965, and the

successes of Nikephoros culminated in 969 with the recapture of

Antioch

, which he incorporated as a province of

the Empire. His successor John Tzimiskes recaptured Damascus,

Beirut

,

Acre

,

Sidon

,

Caesarea

, and

Tiberias

, putting Byzantine armies within

striking distance of Jerusalem, although the Muslim power centers in Iraq and

Egypt were left untouched. After much campaigning in the north, the last Arab

threat to Byzantium, the rich province of Sicily, was targeted in 1025 by

Basil II

, who died before the expedition could

be completed. Nevertheless, by that time the Empire stretched from the straits

of Messina

to the

Euphrates

and from the Danube to Syria.

Wars

against the Bulgarian Empire

Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025).