|

Byzantine Empire

Anonymous Class

G

Bronze Follis 27mm (7.29 grams)

Struck during the reign of

Romanus IV

, Diogenes –

Byzantine Emperor: 1 January 1068 A.D. – 19 August 1071 A.D.

Reference: Sear 1867

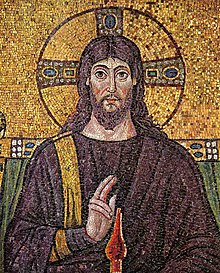

Bust of

Christ

facing , wearing a nimbus crown, pallium and colobium, and

raising right hand in benediction;

in left hand, scroll; to left, IC; to right, XC; border of large pellets.

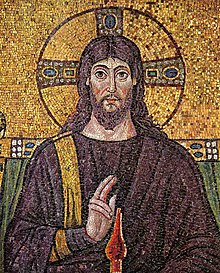

Facing bust of the

Virgin orans

, nimbate and wearing pallium and maphorium; to

left, MP; to right,

ΘV;

border of large pellets.

For more than a century, the production of Follis denomination Byzantine coins

had religious Christian motifs which included included

Jesus Christ, and even Virgin Mary. These coins were designed to honor Christ

and recognize the subservient role of the Byzantine emperor, with many of the

reverse inscriptions translating to “Jesus Christ King of Kings” and “May Jesus

Christ Conquer”. The Follis denomination coins

were the largest bronze denomination coins issued by the Byzantine empire, and

their large size, along with the Christian motif make them a popular coin type

for collectors. This series ran from the period of Byzantine

emperors John I (969-976 A.D.) to Alexius I (1081-1118 A.D.). The accepted

classification was originally devised by Miss Margaret Thompson with her study

of these types of coins. World famous numismatic

author, David R. Sear adopted this classification system for his book entitled,

Byzantine Coins and Their Values. The references about this coin site Mr. Sear’s

book by the number that they appear in that work. The class types of coins

included

Class A1,

Class A2,

Class B,

Class C,

Class D,

Class E,

Class F,

Class G,

Class H,

Class I,

Class J,

Class K. Read more and see examples of these coins by reading the

JESUS CHRIST

Anonymous Class A-N Byzantine Follis Coins Reference.

Click here to see all the Jesus Christ Anonymous Follis coins for sale.

Click here to see all coins bearing Jesus Christ or related available for sale.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

Jesus of Nazareth (c. 5 BC/BCE – c. 30 AD/CE), also

referred to as Jesus Christ or simply Jesus, is the central figure

of

Christianity. Most

Christian denominations

venerate him as

God the

Son

incarnated

and believe that he

rose from the dead

after being

crucified

.

The

principal sources of information regarding Jesus are the four

canonical gospels, and most

critical scholars

find them, at least the

Synoptic Gospels, useful for reconstructing Jesus’ life and

teachings. Some scholars believe apocryphal texts such as the

Gospel of Thomas and the

Gospel according to the Hebrews

are also

relevant

.

Most critical historians agree that Jesus was a

Jew

who was regarded as a teacher and

healer

, that he

was baptized

by

John the Baptist, and

was crucified

in

Jerusalem

on the orders of the

Roman Prefect

Judaea,

Pontius Pilate, on the charge of

sedition

against the Roman Empire

. Critical Biblical scholars and

historians have offered competing descriptions of Jesus as a self-described

Messiah,

as the leader of an apocalyptic movement, as an itinerant sage, as a charismatic

healer, and as the founder of an independent religious movement. Most

contemporary scholars of the

Historical Jesus consider him to have been an independent,

charismatic founder of a Jewish restoration movement, anticipating an imminent

apocalypse. Other prominent scholars, however, contend that Jesus’ “Kingdom

of God” meant radical personal and social transformation instead of a

future apocalypse.

Christians traditionally believe that Jesus was

born of a virgin

:529–32

performed

miracles

,:358–59

founded

the Church

,

rose from the dead

, and

ascended

into

heaven,:616–20

from which he

will return

.:1091–109

Most Christian scholars today present Jesus as the awaited Messiah promised in

the

Old Testament and as God, arguing that he fulfilled many Messianic

prophecies of the Old Testament

. The majority of Christians

worship Jesus as the incarnation of God the Son, one of three divine persons of

a reject Trinitarianism

Trinity, wholly or partly,

believing it to be non-scriptural.

The Virgin Orans, Oranta (The Great

Panagia)

(Ukrainian:

Оранта) is a well-known

Orthodox Christian

depiction of the

Virgin Mary

in prayer with extended arms. It is

stored in the

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev

in

Ukraine.

The 6 meter high mosaic

is located in the vault of the chancel.

The icon has been present in the Cathedral since its foundation by

Yaroslav I the Wise

in the 12th century.

The Virgin’s solemn and static posture, the characteristic folds of her

garments, and her pensive expression indicate the design was strongly influenced

by

Byzantine art.

The image is considered as one of the greatest sacred symbols in Ukraine, a

palladion

defending the people of the country.

It has been called an “Undestructible Wall” or “Unmoveable Wall”. Legend says

that as long as the Theotokos

is extending Her arms over

Kiev,

the city will stand indestructible.

The

embroidered

handkerchief on the belt of the

Mother of God is popularly thought to be for wiping away the tears of those who

come before her with their problems and concerns.

In 1997 the National Bank of Ukraine

issued commemorative

coins “Orante” (“Oranta”) within the “Spiritual Treasures of Ukraine” series.

Romanos IV Diogenes or Romanus IV Diogenes (Greek: Ρωμανός

Δ΄ Διογένης, Rōmanos IV Diogenēs) was a member of the

Byzantine

military aristocracy who, after his marriage to the widowed

empress

Eudokia Makrembolitissa

was crowned

Byzantine emperor

and reigned from 1068 to 1071. During his reign he was

determined to halt the decline of the Byzantine military and stop Turkish

incursions into the Byzantine Empire, but in 1071 he was captured and his army

routed at the

Battle of Manzikert

. Upon his capture he was overthrown in a palace coup,

and when released he was quickly defeated and detained by members of the

Doukas

family.

In 1072, he was blinded and sent to a monastery where he died of his wounds.

//

Accession

to the throne

Romanos Diogenes was the son of

Constantine Diogenes

and a member of a prominent and powerful

Cappadocian

family, connected by birth to most of the great aristocratic nobles in

Asia Minor

. Courageous and generous, but also quite impetuous, his military

talents had seen him rise with distinction in the army, but he was eventually

convicted of attempting to usurp the throne of the sons of

Constantine X

Doukas in 1067. While waiting to receive his sentence from the

regent

Eudokia Makrembolitissa

, he was summoned into her presence and advised that

she had pardoned him and that furthermore she had chosen him to be her husband

and the guardian of her sons as emperor. She took this course of action firstly

due to her concern that unless she managed to find a powerful husband, she could

easily lose the regency to any unscrupulous noble, and secondly because she was

infatuated with the popular Romanus. Her decision was met with little protest as

the Seljuk

Turks had overrun much of Cappadocia and had even taken the important city of

Caesarea

,

meaning that the army needed to be placed under the command of an able and

energetic general.

The problem Romanus and Eudokia had in executing this plan was that Eudokia’s

deceased husband, Constantine X, had made her swear an oath never to remarry.

She approached the

Patriarch

John Xiphilinos

and convinced him both to hand over the written oath she had

signed to this effect, and to have him pronounce that he was in favour of a

second marriage for the good of the state. The

Senate

agreed,

and on January 1, 1068 Romanus married the empress and was crowned Emperor of

the Romans.

Campaigns

against the Turks

Romanus IV was now the senior emperor and guardian of his stepsons and junior

co-emperors,

Michael VII

,

Konstantios Doukas

, and

Andronikos Doukas

. However, his elevation had antagonised not only the

Doukas

family,

in particular the

Caesar

,

John Doukas

who led the opposition of the palace officials to Romanos’

authority, but also the

Varangian Guard

, who openly expressed their discontent at the marriage of

Eudokia. Romanos therefore decided that he could only exercise his authority by

placing himself at the head of the army in the field, thereby focusing the whole

government’s attention on the war against the Turks.

By 1067

, the

Turks had been making incursions at will into

Mesopotamia

,

Melitene

, Syria

,

Cilicia

and

Cappadocia, culminating with the sack of Caesarea and the plundering of the

Church of

St Basil

. That winter they camped on the frontiers of the empire, and waited

for the next year’s campaigning season. Romanos was confident of Byzantine

superiority on the field of battle, looking on the Turks as little more than

hordes of robbers who would melt away at the first encounter. He did not take

into account the degraded state of the Byzantine forces which had suffered years

of neglect from his predecessors, in particular Constantine X. His forces,

mostly composed of

Sclavonian

,

Armenian

,

Bulgarian

,

and Frankish

mercenaries, were ill-disciplined, disorganised and uncoordinated, and he was

not prepared to spend time in upgrading the arms, armour or tactics of the once

feared Byzantine army.

Campaign

of 1068

The first military operations of Romanos did achieve a measure of success,

reinforcing his opinions about the outcome of the war.

Antioch

was

exposed to the

Saracens

of Aleppo

who, with help from Turkish troops, began an attempt to reconquer the

Byzantine province of Syria. Romanos began marching to the southeastern frontier

of the empire to deal with this threat, but as he was advancing towards

Lykandos

,

he received word that a Seljuk army had made an incursion into

Pontus

and

plundered Neocaesarea

. Immediately he selected a small mobile force and quickly raced

through

Sebaste

and

the mountains of

Tephrike

to encounter the Turks on the road, forcing them to abandon their

plunder and release their prisoners, though a large number of the Turkish troops

managed to escape.

Returning south, Romanos rejoined the main army and they continued their

advance through the passes of

Mount Taurus

to the north of

Germanicia

and proceeded to invade the

Emirate

of

Aleppo. Romanos captured

Hierapolis

which he fortified in order to provide protection against further incursions

into the south-eastern provinces of the empire. He then engaged in further

fighting against the Saracens of Aleppo but neither side managed a decisive

victory. With the campaigning season reaching its end, Romanos returned north

via

Alexandretta

and the

Cilician Gates to

Podandos

. Here he was advised of another Seljuk raid into

Asia

Minor

which saw them sack

Amorium

, but

they had returned to their base so fast that Romanos was in no position to give

chase, and he eventually reached

Constantinople

by

January

1069.

Campaign

of 1069

Plans for the following year’s campaigning were initially thrown into chaos

by a rebellion by one of Romanos’

Norman

mercenaries

, Crispin, who led a contingent of Frankish troops in the pay of

the empire. Possibly due to Romanos not paying them on time, they began

plundering the countryside near where they were stationed, and attacking the

imperial tax collectors. Although Crispin was captured and exiled to

Abydos

, the Franks continued to ravage the

Armeniac Theme

for some time. In the meantime, the land around Caesarea was

again overrun by the Turks, forcing Romanos to spend precious time and energy in

expelling the Turks from Cappadocia. Desperate to begin his campaign proper, he

ordered the execution of all prisoners, even a Seljuk chieftain who offered to

pay an immense ransom for his life. Having brought a measure of peace to the

province, Romanos marched towards the

Euphrates

via

Melitene

, and crossed the river at

Romanopolis

, hoping to take

Akhlat

on Lake Van

and thus protect the Armenian frontier.

Romanos placed himself at the head of a substantial body of troops, and began

his march towards Akhlat, leaving the bulk of the army under the command of

Philaretos Brachamios

with orders to defend the Mesopotamian frontier.

Philaretos was soon defeated by the Turks, whose advance on

Iconium

forced

Romanos to abandon his plans and return to Sebaste. He sent orders to the

Dux of Antioch to

secure the passes at

Mopsuestia

,

while he attempted to run down the Turks at

Heracleia

.

The Turks were soon hemmed in the mountains of

Cilicia

, but

managed to escape to Aleppo after abandoning their plunder. Romanos once again

returned to Constantinople without the great victory he was hoping for.

Affairs

at Constantinople

The year 1070

saw Romanos detained at Constantinople while he dealt with many outstanding

administrative issues, including the imminent fall of

Bari into

Norman

hands. They had been besieging it since 1068, but it had taken

Romanos two years to finally get around to doing anything about it. He ordered a

relief fleet to set sail, containing sufficient provisions and troops to enable

them to hold out for much longer. But the fleet was intercepted and defeated by

a Norman squadron under the command of

Roger

, the

younger brother of

Robert Guiscard

,

forcing the final remaining outpost of Byzantine authority in

Italy

to

surrender on April 15, 1071.

While this was playing out, Romanos was undertaking a number of unpopular

reforms at home. He reduced a great deal of unnecessary public expenditure that

was wasted on useless court ceremonials and beautifying the capital. He reduced

the public salaries that were paid to much of the court nobility, as well as

reducing the profits of tradesmen. His preoccupation with the military had also

made him unpopular with the provincial governors and the military hierarchy, as

he was determined to ensure they could not abuse their positions, especially

through corrupt practices. He incurred the displease of the mercenaries by

enforcing much need discipline. Romanos was also deeply unpopular with the

common people, as he neglected to entertain them with games at the

hippodrome

, nor did he alleviate the burdens of the peasants in the

provinces. All this animosity would help his enemies when the time came that

they moved against him.

Nevertheless, he did not forget his principal target, the Turks. Being unable

to go on campaign himself, he entrusted the imperial army to one of his

generals,

Manuel Komnenos

, nephew of the former emperor

Isaac I

, and elder brother to the future emperor

Alexios

. He managed to engage the Turks in battle, but was defeated and

taken prisoner by a Turkish general named

Khroudj

. Manuel convinced Khroudj to go to Constantinople and see Romanos in

person in order to conclude an alliance, which was soon completed. This act

motivated the Seljuk Sultan

Alp Arslan

to attack the Byzantine Empire, besieging and capturing the important Byzantine

fortress of

Manzikert

.

Battle

of Manzikert and capture by Alp Arslan

Early in the spring of 1071, Romanos marched at the head of a large army with

the intent of recovering Manzikert. It was soon evident that the army had a

serious discipline problem, with soldiers regularly pillaging the area around

their nightly camps. When Romanos attempted to enforce some stricter discipline,

a whole regiment of German mercenaries mutinied, which the emperor only managed

to control with the greatest difficulty.

Believing that Alp Arslan was nowhere near Manzikert, he decided to divide

his army. One part of the army he dispatched to attack Akhlat, at that time in

possession of the Turks. Romanos himself advanced with the main body of the army

on Manzikert, which he soon recaptured. At this point his advance guard met the

Seljuk army which was rapidly approaching Manzikert. Romanos ordered the forces

attacking Akhlat to rejoin the army, but their portion of the army unexpectedly

came across another large Turkish army, forcing their retreat back into

Mesopotamia. Already under strength, Romanos’ army was further weakened when his

Uzes mercenaries deserted to the Turks.

Arslan had no desire to take on the Byzantine army, and so proposed a peace

treaty with favourable terms for Romanos. The emperor, eager for a decisive

military victory, rejected the offer, and both armies lined up for a battle that

took place on August 26, 1071. The battle lasted all day without either side

gaining any decisive advantage when the emperor ordered a part of his centre to

return to camp but the order was misunderstood by the right wing.

Andronikos Doukas

, who commanded the reserves, was the son of Caesar John

Doukas, and he took advantage of the confusion to betray Romanos by marching

away from the battle with some 30,000 men instead of covering the emperor’s

retreat, claiming that Romanos was dead. The Turks now began to press in on the

Byzantine army.

When Romanos discovered what had happened, he tried to recover the situation

by making a defiant stand. He fought valiantly when his horse was finally killed

from under him. Receiving a wound in the hand which prevented him from wielding

a sword, he was soon taken prisoner.

According to a number of Byzantine historians, including

John Skylitzes

,

Arslan at first had difficulty believing the dusty and tattered warrior brought

before him was the Roman Emperor. He then stepped down from his seat and placed

his foot on Romanos’ neck. But after this sign of ritual humiliation, Arslan

raised Romanos from the ground, and ordered him to be treated like a king. From

then on he treated him with extreme kindness, never saying a cruel word to him

in the Emperor’s eight-day stay in his camp, and who then released him in

exchange for a treaty and the promise of a hefty ransom. At first Alp Arslan

suggested a ransom of 10,000,000

nomismata

to Romanos IV, but later reduced it to 1,500,000 nomismata

with a further 360,000 nomismata annually.

Betrayal

In the meantime, the opposition faction scheming against Romanos IV decided

to exploit the situation. The Caesar John Doukas and

Michael Psellos

forced Eudokia to retire to a monastery, and easily prevailed upon Michael VII

to declare Romanos IV deposed. They then refused to honor the agreement made

between Arslan and the former emperor. Romanos soon returned and he and the

Doukas family gathered troops. A battle was fought at

Doceia

between Constantine and Andronikos Doukas and Romanos, in which the

army of Romanos was defeated, forcing him to retreat to the fortress of

Tyropoion

, and from there to

Adana

in Cilicia.

Pursued by Andronikos, he was eventually forced to surrender by the garrison at

Adana upon receiving assurances of his personal safety. Before leaving the

fortress, he collected all the money he could lay his hands on and sent it to

the Sultan as proof of his good faith, along with a message: “As emperor, I

promsed you a ransom of a million and a half. Dethroned, and about to become

dependent upon others, I send you all I possess as proof of my gratitude.”

Andronikos stipulated that his life would be spared if he resigned the purple

and retired into a monastery. Romanos agreed, and this agreement was ratified at

Constantinople. However, John Doukas reneged on the agreement, and sent men to

have Romanos

cruelly blinded

on (June 29, 1072), before sending him into exile to

Kınalıada

in the

Sea of Marmara

.

Leaving him without an assistant, his wound became infected, and he was soon

enduring a painfully lingering death. The final insult was given a few days

before his death, when Romanos received a letter from John Doukas,

congratulating him on the loss of his eyes. He finally died, praying for the

forgiveness of his sins, and his wife Eudokia was permitted to honor his remains

with a magnificent funeral.

Family

By his first wife Anna, a daughter of

Alusian of

Bulgaria

, Romanos IV Diogenes had at least one son:

- Constantine Diogenes, who was married to Theodora, sister of

Alexios I

Komnenos

. This marriage was arranged by

Anna Dalassena

after the death of Romanos IV, but it was shortlived, as

Constantine perished under the walls of

Antioch

in 1073 while serving with his brother-in-law Isaac Komnenos.

By his second wife, the Empress

Eudokia Makrembolitissa

, he had:

-

Nikephoros Diogenes

- Leo Diogenes

|