|

Byzantine – Latin Rulers of Constantinople 1204-1261 A.D.

Billon Trachea 30mm (3.38 grams) Constantinople mint: 1204-1261 A.D.

Reference: Sear 2021

Virgin enthroned.

Emperor standing, holding labarum and cross on globe.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

Labarum of Constantine I, displaying the “Chi-Rho” symbol above.

The labarum was a

vexillum

(military standard) that displayed

the “Chi-Rho”

symbol

☧

, formed from the first two

Greek letters

of the word “Christ”

—

Chi

and

Rho

. It was first used by the

Roman emperor

Constantine I

. Since the vexillum consisted of

a flag suspended from the crossbar of a cross, it was ideally suited to

symbolize the

crucifixion

of

Christ

.

Later usage has sometimes regarded the terms “labarum” and “Chi-Rho” as

synonyms. Ancient sources, however, draw an unambiguous distinction between the

two.

Etymology

Beyond its derivation from Latin labarum, the etymology of the word is

unclear. Some derive it from Latin /labāre/ ‘to totter, to waver’ (in the sense

of the “waving” of a flag in the breeze) or laureum [vexillum] (“laurel

standard”).

According to the

Real Academia Española

, the related

lábaro

is also derived from Latin labărum

but offers no further derivation from within Latin, as does the Oxford English

Dictionary.[5]

An origin as a loan into Latin from a Celtic language or

Basque

has also been postulated. There is a

traditional Basque symbol called the

lauburu

; though the name is only attested from

the 19th century onwards the motif occurs in engravings dating as early as the

2nd century AD.

Vision of Constantine

A coin of Constantine (c.337) showing a depiction of his labarum

spearing a serpent.

On the evening of October 27, 312, with his army preparing for the

Battle of the Milvian Bridge

, the emperor

Constantine I

claimed to have had a vision

which led him to believe he was fighting under the protection of the

Christian God

.

Lactantius

states that, in the night before the

battle, Constantine was commanded in a dream to “delineate the heavenly sign on

the shields of his soldiers”. He obeyed and marked the shields with a sign

“denoting Christ”. Lactantius describes that sign as a “staurogram”, or a

Latin cross

with its upper end rounded in a

P-like fashion, rather than the better known

Chi-Rho

sign described by

Eusebius of Caesarea

. Thus, it had both the

form of a cross and the monogram of Christ’s name from the formed letters “X”

and “P”, the first letters of Christ’s name in Greek.

From Eusebius, two accounts of a battle survive. The first, shorter one in

the

Ecclesiastical History

leaves no doubt that

God helped Constantine but doesn’t mention any vision. In his later Life of

Constantine, Eusebius gives a detailed account of a vision and stresses that

he had heard the story from the emperor himself. According to this version,

Constantine with his army was marching somewhere (Eusebius doesn’t specify the

actual location of the event, but it clearly isn’t in the camp at Rome) when he

looked up to the sun and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek

words

Ἐν Τούτῳ Νίκα

. The traditionally employed

Latin translation of the Greek is

in hoc signo vinces

— literally “In this

sign, you will conquer.” However, a direct translation from the original Greek

text of Eusebius into English gives the phrase “By this, conquer!”

At first he was unsure of the meaning of the apparition, but the following

night he had a dream in which Christ explained to him that he should use the

sign against his enemies. Eusebius then continues to describe the labarum, the

military standard used by Constantine in his later wars against

Licinius

, showing the Chi-Rho sign.

Those two accounts can hardly be reconciled with each other, though they have

been merged in popular notion into Constantine seeing the Chi-Rho sign on the

evening before the battle. Both authors agree that the sign was not readily

understandable as denoting Christ, which corresponds with the fact that there is

no certain evidence of the use of the letters chi and rho as a Christian sign

before Constantine. Its first appearance is on a Constantinian silver coin from

c. 317, which proves that Constantine did use the sign at that time, though not

very prominently.

He made extensive use of the Chi-Rho and the labarum only later in the conflict

with Licinius.

The vision has been interpreted in a solar context (e.g. as a

solar halo

phenomenon), which would have been

reshaped to fit with the Christian beliefs of the later Constantine.

An alternate explanation of the intersecting celestial symbol has been

advanced by George Latura, which claims that Plato’s visible god in Timaeus

is in fact the intersection of the Milky Way and the Zodiacal Light, a rare

apparition important to pagan beliefs that Christian bishops reinvented as a

Christian symbol.

Eusebius’ description of the labarum

“A Description of the Standard of the Cross, which the Romans now call the

Labarum.” “Now it was made in the following manner. A long spear, overlaid with

gold, formed the figure of the cross by means of a transverse bar laid over it.

On the top of the whole was fixed a wreath of gold and precious stones; and

within this, the symbol of the Saviour’s name, two letters indicating the name

of Christ by means of its initial characters, the letter P being intersected by

X in its centre: and these letters the emperor was in the habit of wearing on

his helmet at a later period. From the cross-bar of the spear was suspended a

cloth, a royal piece, covered with a profuse embroidery of most brilliant

precious stones; and which, being also richly interlaced with gold, presented an

indescribable degree of beauty to the beholder. This banner was of a square

form, and the upright staff, whose lower section was of great length, of the

pious emperor and his children on its upper part, beneath the trophy of the

cross, and immediately above the embroidered banner.”

“The emperor constantly made use of this sign of salvation as a safeguard

against every adverse and hostile power, and commanded that others similar to it

should be carried at the head of all his armies.”

Iconographic career under Constantine

Coin of

Vetranio

, a soldier is holding two

labara. Interestingly they differ from the labarum of Constantine in

having the Chi-Rho depicted on the cloth rather than above it, and

in having their staves decorated with

phalerae

as were earlier Roman

military unit standards.

The emperor

Honorius

holding a variant of the

labarum – the Latin phrase on the cloth means “In the name of Christ

[rendered by the Greek letters XPI] be ever victorious.”

Among a number of standards depicted on the

Arch of Constantine

, which was erected, largely

with fragments from older monuments, just three years after the battle, the

labarum does not appear. A grand opportunity for just the kind of political

propaganda that the Arch otherwise was expressly built to present was missed.

That is if Eusebius’ oath-confirmed account of Constantine’s sudden,

vision-induced, conversion can be trusted. Many historians have argued that in

the early years after the battle the emperor had not yet decided to give clear

public support to Christianity, whether from a lack of personal faith or because

of fear of religious friction. The arch’s inscription does say that the Emperor

had saved the

res publica

INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS

MENTIS MAGNITVDINE (“by greatness of mind and by instinct [or impulse]

of divinity”). As with his predecessors, sun symbolism – interpreted as

representing

Sol Invictus

(the Unconquered Sun) or

Helios

,

Apollo

or

Mithras

– is inscribed on his coinage, but in

325 and thereafter the coinage ceases to be explicitly pagan, and Sol Invictus

disappears. In his

Historia Ecclesiae

Eusebius further reports

that, after his victorious entry into Rome, Constantine had a statue of himself

erected, “holding the sign of the Savior [the cross] in his right hand.” There

are no other reports to confirm such a monument.

Whether Constantine was the first

Christian

emperor supporting a peaceful

transition to Christianity during his rule, or an undecided pagan believer until

middle age, strongly influenced in his political-religious decisions by his

Christian mother

St. Helena

, is still in dispute among

historians.

As for the labarum itself, there is little evidence for its use

before 317.In the course of Constantine’s second war against Licinius in

324, the latter

developed a superstitious dread of Constantine’s standard. During the

attack of

Constantine’s troops at the

Battle of Adrianople

the guard of the labarum

standard were directed to move it to any part of the field where his soldiers

seemed to be faltering. The appearance of this talismanic object appeared to

embolden Constantine’s troops and dismay those of Licinius.At the final battle of the war, the

Battle of Chrysopolis

, Licinius, though

prominently displaying the images of Rome’s pagan pantheon on his own battle

line, forbade his troops from actively attacking the labarum, or even looking at

it directly.[16]

Constantine felt that both Licinius and

Arius

were agents of Satan, and associated them

with the serpent described in the

Book of Revelation

(12:9).

Constantine represented Licinius as a snake on his coins.

Eusebius stated that in addition to the singular labarum of Constantine,

other similar standards (labara) were issued to the Roman army. This is

confirmed by the two labara depicted being held by a soldier on a coin of

Vetranio

(illustrated) dating from 350.

Later usage

Modern ecclesiastical labara (Southern Germany).

The emperor

Constantine Monomachos

(centre

panel of a Byzantine enamelled crown) holding a miniature labarum

Mary variously called

Saint

Mary, Mother Mary, the Virgin Mary, the

Theotokos

,

the

Blessed Virgin Mary

, Mary,

Mother of God

, and, in

Islam

, as

Maryam

, mother of

Isa

‘, was an

Israelite

Jewish

woman of Nazareth

in Galilee

who lived in the late 1st century BC and early 1st century AD, and

is considered by Christians to be the first

proselyte

to Christianity

. She is identified in the

New

Testament

and in the

Qur’an

as the mother of

Jesus

through

divine intervention

. Christians hold her son Jesus to be

Christ

(i.e.

the messiah

)

and God

the Son

Incarnate

(see

Trinitarian monotheism

), whereas Muslims regard Jesus as the messiah and

the most important prophet of God sent to the people of Israel (and the

second-most-important prophet of all, lesser than

Muhammad

alone).

The

canonical gospels

of

Matthew

and

Luke

describe Mary as a virgin (Greek παρθένος, parthénos).

Traditionally,

Christians

believe that she conceived her son miraculously by the agency of

the

Holy Spirit

.

Muslims

believe that she conceived by the command of God. This took place

when she was already

betrothed

to

Saint

Joseph

and was awaiting the concluding rite of marriage, the formal

home-taking ceremony.

She married Joseph and accompanied him to

Bethlehem

,

where Jesus was born.

In keeping with Jewish custom, the betrothal would have taken place when she was

around 12, and the birth of Jesus about a year later.

The New Testament begins its account of Mary’s life with the Annunciation,

when the angel Gabriel

appeared to her and announced her divine selection to be the mother

of Jesus. Church tradition and early non-biblical writings state that her

parents were an elderly couple,

Saint Joachim

and

Saint Anne

.

The Bible records Mary’s role in key events of the life of Jesus from his

conception to his Ascension.

Apocryphal

writings tell of her subsequent death and bodily

assumption

into heaven.

Christians of the

Catholic Church

, the

Eastern Orthodox Church

,

Oriental Orthodox Church

,

Anglican Communion

, and

Lutheran

churches believe that Mary, as mother of Jesus, is the Mother of

God and the

Theotokos

,

literally Bearer of God. Mary has been venerated since

Early Christianity

.

Throughout the ages she has been a favorite subject in Christian art, music, and

literature.

There is significant diversity in the

Marian

beliefs

and devotional practices of major Christian traditions. The Catholic

Church has a number of

Marian dogmas

, such as the

Immaculate Conception of Mary

the

Perpetual Virginity of Mary

, and the

Assumption of Mary

into Heaven. Catholics refer to her as

Our Lady

and

venerate

her as the

Queen of Heaven

and

Mother of the Church

; most

Protestants

do not share these beliefs.[8][9]

Many Protestants see a minimal role for Mary within Christianity, based on the

brevity of biblical references.

In ancient sources

New Testament

The

Annunciation

by

Eustache Le Sueur

, an example of 17th century

Marian art

. The

Angel

Gabriel

announces to Mary her pregnancy with

Jesus

and offers her

White Lillies

The New Testament account of her humility and obedience to the message of

God have made her an exemplar for all ages of Christians. Out of the details

supplied in the New Testament by the Gospels about the maid of Galilee,

Christian piety and theology have constructed a picture of Mary that

fulfills the prediction ascribed to her in the Magnificat (Luke 1:48):

“Henceforth all generations will call me blessed.”

— “Mary.” Web: 29Sep2010 Encyclopædia

Britannica Online.

The Icon

of Our Lady of the Sign (Greek:

Panagia

or Παναγία;

Old Church

Slavonic

: Ikona Bozhey

Materi “Znamenie”;

Polish

:

Ikona Bogurodzicy “Znak” ‘) is

the term for a particular type of

icon

of the Theotokos

(Virgin Mary), facing the viewer directly, depicted either full length or

half, with her hands raised in the

orans

position, and with the image of the

Child Jesus

depicted within a round

aureole

upon her breast.

Our Lady of the Sign (18th century,

iconostasis

Kizhi

monastery, Karelia, Russia).

The icon depicts the Theotokos during the

Annunciation

at the moment of saying, “May it be done to me according to your word.”(Luke

1:38). The image of the Christ child represents him at the

moment of his conception in the womb of the Virgin. He is depicted not as a

fetus, but rather vested in divine robes, and often holding a scroll,

symbolic of his role as teacher. Sometimes his robes are gold or white,

symbolizing divine glory; sometimes they are blue and red, symbolizing the

two natures of Christ (see

Christology

).

His face is depicted as that of an old man, indicating the Christian

teaching that he was at one and the same time both a fully human infant and

fully the eternal God, one of the Trinity. His right hand is raised in

blessing.

The term Virgin of the Sign or Our Lady of the Sign is a

reference to the

prophecy

of Isaiah

7:14

:

“Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, a virgin shall

conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name

Immanuel

“.

Such an image is often placed in the

apse

of the sanctuary

of an Orthodox

church

above the

Holy Table

(altar).[2]

As with most Orthodox icons of Mary, the letters ΜΡ ΘΥ (short for ΜΗΤΗΡ

ΘΕΟΥ, “Mother

of Godd“) are usually placed on the upper left and right of

the head of the Virgin Mary.

Platytéra (Greek:

Πλατυτέρα, literally wider or more spacious); poetically, by

containing the

Creator

of the Universe

in her

womb

,

Mary has become Platytera ton ouranon (Πλατυτέρα των Ουρανών): “More

spacious than the heavens”. The Platytéra is traditionally depicted

on the half-dome that stands above the

altarr

.

It is visible high above the

iconostasis

,

and facing down the length of the

nave

of the church. This particular depiction is usually on a dark blue

background, often adorned by golden stars.

History

The depiction of the

Virgin Mary

with her hands upraised in prayer (“orans”) is of very ancient origin in

Christian art

.

In the

mausoleum of St

Agnes

in

Rome

is a depiction dating to the 4th century which depicts the Theotokos with

hands raised in prayer and the infant

Jesus

sitting upon her knees. There is also an ancient Byzantine

icon

of the Mother of God “Nikopea” from the 6th century, where the Virgin Mary

is depicted seated upon a

throne

and holding in her hands an oval shield with the image of “Emmanuel”.

Icons of the Virgin, known as “The Sign”, appeared in

Russia

during the 11th to 12th centuries. The icon became highly venerated in

Russia because of what

Orthodox

Christians

believe to be the miraculous deliverance of

Novgorod

from invasion in the year 1170.

Among the more famous variants of this genre are the Icons of the Mother

of God of

Abalatsk

,

Kursk-Root

,

Mirozh

,

Novgorod

,

Sankt Petersburg

,

Tsarskoye Selo

and Vologda

.

The

Church of St.

Stanislaus Kostka

, one of

Chicago

‘s

famed

Polish Cathedrals

,

is home to a 9-foot-wide (2.7 m) Iconic

Monstrance

of Our Lady of the Sign as part of the planned

Sanctuary

of

The Divine Mercy

that is being constructed adjacent to the church. The Monstrance will be

found within the sanctuary’s adoration

chapel

which will be the focus of 24-hour

Eucharistic

Adoration

and where there will be no liturgies or vocal

prayers, either by individuals or groups as the space will be strictly meant

for private meditation and contemplation.

The English name “Mary” comes from the

Greek

Μαρία, which is a shortened form of Μαριάμ. The New

Testament name was based on her original

Hebrew

name מִרְיָם or

Miryam

.

Both Μαρία and Μαριάμ appear in the New Testament.

Specific references

- Luke’s gospel mentions Mary most often, identifying her by name twelve

times, all of these in the infancy narrative.

- Matthew’s gospel mentions her by name five times, four of these in the infancy narrative and only once outside the infancy narrative.

- Mark’s gospel names her only once

(6:3)

and mentions her as Jesus’ mother without naming her in

3:31

.

- John’s gospel refers to her twice but never mentions her by name.

Described as Jesus’ mother, she makes two appearances in John’s gospel. She

is first seen at the wedding at Cana of Galilee

which is mentioned only in the fourth gospel. The second reference in John,

also exclusively listed this gospel, has the mother of Jesus standing near

the cross of her son together with the (also unnamed) “disciple whom Jesus

loved.

John 2:1-12

is the only text in the canonical gospels in which Mary

speaks to (and about) the adult Jesus.

- In the Book of Acts, Luke’s second writing, Mary and the “brothers

of Jesus” are mentioned in the company of the eleven who are gathered in

the upper room after the ascension.

- In the Book of Revelation,[12:1,5-6]

John’s apocalypse never explicitly identifies the “woman clothed with the

sun” as Mary of Nazareth, the mother of Jesus. However, some interpreters

have made that connection.

Family and early life

The New Testament tells little of Mary’s early history. The 2nd century

Protoevangelium of James

is the first source to name her parents as

Joachim

and

Anne

.

According to Luke, Mary was a cousin of

Elizabeth

, wife of the priest

Zechariah

of the priestly division of

Abijah

, who was

herself part of the

lineage of Aaron

and so of the tribe of Levi.

Some of those who consider that the relationship with Elizabeth was on the

maternal side, consider that Mary, like Joseph, to whom she was betrothed, was

of the House of David and so of the tribe of Judah, and that the

genealogy of Jesus

presented in

Luke 3

from

Nathan, third son of David and Bathsheba

, is in fact the genealogy of Mary,

while the genealogy from

Solomon

given

in Matthew 1

is that of Joseph.

(Aaron’s wife

Elisheba

was of the tribe of Judah, so all his descendents are from both

Levi and Judah.)

The Virgin’s first seven steps mosaic from

Chora Church

, c. 12th century.

Mary resided in “her own house”

in Nazareth

in Galilee

,

possibly with her parents, and during her betrothal – the first stage of a

Jewish marriage

– the

angel

Gabriel

announced to her that she was to be the mother of the promised

Messiah

by

conceiving him through the Holy Spirit.

After a number of months, when Joseph was told of her conception in a dream by

“an angel of the Lord”, he was surprised; but the angel told him to be unafraid

and take her as his wife, which Joseph did, thereby formally completing the

wedding rites.

Since the angel Gabriel had told Mary that Elizabeth – having previously been barren – was then

miraculously pregnant, Mary hurried to see Elizabeth, who was living with her

husband Zechariah in “Hebron, in the hill country of Judah”.

Mary arrived at the house and greeted Elizabeth who called Mary “the mother of

my Lord”, and Mary spoke the words of praise that later became known as the

Magnificat

from her first word in the

Latin

version.

After about three months, Mary returned to her own house.

According to the Gospel of Luke, a decree of the Roman emperor

Augustus

required that Joseph return to his hometown of

Bethlehem

to be

taxed

. While he was there with Mary, she gave birth to Jesus; but because

there was no place for them in the inn, she used a

manger

as a

cradle.

After eight days, he was

circumcised

according to Jewish law, and named “JESUS”

in accordance with the instructions that the angel had given to Mary in

Luke 1:31

, and Joseph was likewise told to call him Jesus in

Matthew 1:21

.

After Mary continued in the “blood of her purifying” another 33 days for a

total of 40 days, she brought her burnt offering and sin offering to the temple,

so the priest could make atonement for her sins, being cleansed from her blood.

They also presented Jesus – “As it is written in the law of the Lord, Every male

that openeth the womb shall be called holy to the Lord” . After the prophecies of

Simeon

and the prophetess

Anna

in

Luke 2:25-38

concluded, Joseph and Mary took Jesus and “returned into

Galilee, to their own city Nazareth.”.

Sometime later, the “wise

men” showed up at the “house” where Jesus and his family were staying, and

they fled by night and stayed in Egypt for awhile, and returned after Herod died

in 4 BC and took up residence in Nazareth.

Mary in the life of

Jesus

Stabat Mater

in the

Valle Romita Polyptych

by

Gentile da Fabriano

, c. 1410-1412

Mary is involved in the only event in Jesus’ adolescent life that is recorded

in the New Testament. At the age of twelve Jesus, having become separated from

his parents on their return journey from the

Passover

celebration in

Jerusalem

,

was found among the teachers in the temple.

After Jesus’ baptism

by

John the Baptist

and his temptations by the devil in the desert, Mary was

present when, at her suggestion, Jesus worked his first

Cana miracle during

a marriage they attended, by

turning water into wine

.

Subsequently there are events when Mary is present along with

James

, Joseph, Simon, and

Judas

, called Jesus’ brothers, and unnamed “sisters”.

Following Jerome

,

the Church Fathers

interpreted the words translated as “brother” and “sister” as

referring to close relatives.

There is also an incident in which Jesus is sometimes interpreted as

rejecting his family. “And his mother and his brothers arrived, and standing

outside, they sent in a message asking for him[ 3:21Mk]

… And looking at those who sat in a circle around him, Jesus said, ‘These are

my mother and my brothers. Whoever does the will of God is my brother, and

sister, and mother.'”

Mary is also depicted as being present among the

women at the crucifixion

during the

crucifixion

standing near “the disciple whom Jesus loved” along with Mary of

Clopas and

Mary Magdalene

,[ 19:25-26Jn]

to which list

Matthew 27:56

adds “the mother of the sons of Zebedee”, presumably the

Salome

mentioned in

Mark 15:40

. This representation is called a

Stabat Mater

.

Mary, cradling the dead body of her Son, while not recorded in the Gospel

accounts, is a common motif in art, called a “pietà”

or “pity”.

After the

Ascension of Jesus

In

Acts 1:26, especially v. 14,

Mary is the only one to be mentioned by

name other than the

eleven apostles

, who abode in the

upper room

,

when they returned from mount Olivet. (It is not stated where the later

gathering of about one hundred and twenty disciples was located, when they

elected

Matthias

to fill the office of

Judas Iscariot

who perished.) Some speculate that the “elect lady” mentioned

in

2 John 1:1

may be Mary. From this time, she disappears from the

biblical accounts, although it is held by Catholics that she is again portrayed

as the heavenly woman of

Revelation

.

Her death is not recorded in the scripture. However, Catholic and Orthodox

tradition and doctrine have her

assumed

(taken bodily) into

Heaven

. Belief in the corporeal assumption of Mary is universal to

Catholicism

, in both

Eastern

and

Western Catholic Churches

, as well as the

Eastern Orthodox Church

.

Coptic Churches

, and parts of the

Anglican Communion

and

Continuing Anglican Churches

.

Later

Christian writings and traditions

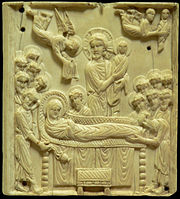

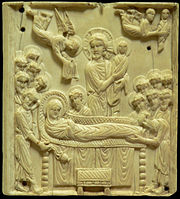

The Dormition

: ivory plaque, late 10th-early 11th century (Musée

de Cluny).

According to the

apocryphal

Gospel of James

Mary was the daughter of

Saint Joachim

and

Saint Anne

.

Before Mary’s conception Anna had been barren. Mary was given to service as a

consecrated virgin in the Temple in Jerusalem when she was three years old, much

like

Hannah

took

Samuel

to the

Tabernacle

as recorded in the

Old

Testament

.[29]

Some

apocryphal

accounts state that at the time of her betrothal to Joseph Mary

was 12–14 years old, and he was ninety years old, but such accounts are

unreliable.

According to

Sacred Tradition

, Mary died surrounded by the

apostles

(in either

Jerusalem

or Ephesus

)

between three days and 24 years after Christ’s

ascension

. When the apostles later opened her tomb, they found it to be

empty and they concluded that she had been

assumed

into Heaven

.

Mary’s Tomb

, an empty tomb in Jerusalem, is attributed to Mary.

The Roman Catholic Church teaches

Mary’s assumption

, but does not teach that she

necessarily died.

Hyppolitus of Thebes

claims that Mary lived for 11 years after the death of

her Son, dying in 41 AD.

The earliest extant biographical writing on Mary is

Life of the Virgin

attributed to the 7th century saint,

Maximus the Confessor

which portrays her as a key element of the

early Christian Church

after the death of Jesus.

In the 19th century, a house near

Ephesus

in

Turkey

was

found, based on the visions of

Anne Catherine Emmerich

, an

Augustinian nun

in Germany

It has since been visited as the

House of the Virgin Mary

by Roman Catholic pilgrims who consider it the

place where Mary lived until her assumption.[41][42][43][44]

The Gospel of John states that Mary went to live with the

Disciple whom Jesus loved

identified as

John the Evangelist

.

Irenaeus

and

Eusebius of Caesarea

wrote in their histories that John later went to

Ephesus, which may provide the basis for the early belief that Mary also lived

in Ephesus with John.

Christian devotion

2nd to 5th centuries

Christian devotion to Mary goes back to the 2nd century and predates the

emergence of a specific Marian liturgical system in the 5th century, following

the

First Council of Ephesus

in 431. The Council itself was held at a church in

Ephesus which had been dedicated to Mary about a hundred years before.

In Egypt the veneration of Mary had started in the 3rd century and the term

Theotokos

was used by Origen

,

the

Alexandrian

Father of the Church.

The earliest known Marian prayer (the

Sub tuum praesidium

, or Beneath Thy Protection) is from the 3rd

century (perhaps 270), and its text was rediscovered in 1917 on a papyrus in

Egypt.

Following the

Edict of Milan

in 313, by the 5th century artistic images of Mary began to

appear in public and larger churches were being dedicated to Mary, e.g.

S. Maria Maggiore

in Rome.

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages saw many legends about Mary, and also her parents and even

grandparents.

Since the Reformation

Key articles on

Mariology

|

General perspective

Mother of Jesus

|

Specific views

Anglican

•

Eastern Orthodox

•

Lutheran

•

Marian veneration

•

Muslim

•

Protestant

•

Roman Catholic

|

Prayers & devotions

Hymns to Mary

•

Hail

Mary

• Rosary

|

Ecumenical

Ecumenical views

|

|

|

Over the centuries, devotion and veneration to Mary has varied greatly among

Christian traditions. For instance, while Protestants show scant attention to

Marian prayers or devotions, of all the saints whom the Orthodox venerate, the

most honored is Mary, who is considered “more honorable than the

Cherubim

and more glorious than the

Seraphim

.”

Orthodox theologian

Sergei Bulgakov

wrote: “Love and veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary is

the soul of Orthodox piety. A faith in Christ which does not include his mother

is another faith, another Christianity from that of the Orthodox church.”

Although the Catholics and the Orthodox may honor and venerate Mary, they do

not view her as divine, nor do they worship her. Catholics view Mary as

subordinate to Christ, but uniquely so, in that she is seen as above all other

creatures.

Similarly Theologian

Sergei Bulgakov

wrote that although the Orthodox view Mary as “superior to

all created beings” and “ceaselessly pray for her intercession” she is not

considered a “substitute for the One Mediator” who is Christ.

“Let Mary be in honor, but let worship be given to the Lord” he wrote.

Similarly, Catholics do not worship Mary, but venerate her. Catholics use the

term

hyperdulia

for Marian veneration rather than

latria

that

applies to God and

dulia

for other saints.

The definition of the three level hierarchy of latria, hyperdulia

and dulia goes back to the

Second Council of Nicaea

in 787.

Devotions to artistic depictions of Mary vary among Christian traditions.

There is a long tradition of

Roman Catholic Marian art

and no image permeates

Catholic art

as does the image of

Madonna and Child

.

The icon of the Virgin is without doubt the most venerated icon among the

Orthodox.

Both Roman Catholics and the Orthodox venerate images and icons of Mary, given

that the

Second Council of Nicaea

in 787 permitted their veneration by Catholics with

the understanding that those who venerate the image are venerating the reality

of the person it represents,

and the 842 Synod of Constantinople established the same for the Orthodox.[66]

The Orthodox, however, only pray to and venerate flat, two-dimensional icons and

not three-dimensional statues.

The

Anglican

position towards Mary is in general more conciliatory than that of

Protestants at large and in a book he wrote about praying with the icons of

Mary,

Rowan Williams

, the

Archbishop of Canterbury

said: “It is not only that we cannot understand

Mary without seeing her as pointing to Christ; we cannot understand Christ

without seeing his attention to Mary”.

Titles

Eleusa

Theotokos

with scenes from the life of Mary, 18th century

Titles to honor Mary or ask for her intercession are used by some Christian

traditions such as the

Eastern Orthodox

or

Catholics

, but not others, e.g. the

Protestants

. Common titles for Mary include

Mother of God

(Theotokos), The Blessed Virgin Mary (also

abbreviated to “BVM”), Our Lady (Notre Dame, Nuestra Señora, Nossa

Senhora, Madonna) and the

Queen of Heaven

(Regina Caeli).

Specific titles vary among

Anglican views of Mary

,

Ecumenical views of Mary

,

Lutheran views of Mary

,

Protestant views on Mary

, and

Roman Catholic views of Mary

,

Latter Day Saints’ views of Mary

,

Orthodox views of Mary

. In addition to

Islamic views on Mary

.

Mary is referred to by the

Eastern Orthodox Church

,

Oriental Orthodoxy

, the

Anglican Church

, and all

Eastern Catholic Churches

as Theotokos, a title recognized at the

Third Ecumenical Council

(held at Ephesus to address the teachings of

Nestorius

,

in 431). Theotokos (and its Latin equivalents, “Deipara” and “Dei genetrix”)

literally means “Godbearer”. The equivalent phrase “Mater Dei”, (Mother of God)

is more common in Latin and so also in the other languages used in the

Western Catholic Church

, but this same phrase in Greek (Μήτηρ Θεοῦ), in the

abbreviated form of the first and last letter of the two words (ΜΡ ΘΥ), is the

indication attached to her image in Byzantine icons. The Council stated that the

Church Fathers “did not hesitate to speak of the holy Virgin as the Mother of

God”.

Some titles have a Biblical basis, for instance the title Queen Mother

has been given to Mary since she was the mother of Jesus, who was sometimes

referred to as the “King of Kings” due to his lineage of King David. The

biblical basis for the term Queen can be seen in the

Gospel of Luke

1:32 and the

Book of Isaiah

9:6, and Queen Mother from

1 Kings 2:19-20

and

Jeremiah 13:18-19

.

Other titles have arisen from reported miracles, special appeals or occasions

for calling on Mary, e.g.

Our Lady of Good Counsel

,

Our Lady of Navigators

or

Our Lady of Ransom

who protects captives.

The three main titles for Mary used by the Orthodox are

Theotokos

,

i.e., Mother of God (Greek Θεοτόκος),

Aeiparthenos

, i.e. Ever Virgin (Greek ἀειπαρθὲνος), as confirmed in

the

Fifth Ecumenical Council

553, and

Panagia

,

i.e., All Holy (Greek Παναγία).

A large number of titles for Mary are used by Roman Catholics, and these titles

have in turn given rise to many artistic depictions, e.g. the title

Our Lady of Sorrows

has resulted in masterpieces such as

Michelangelo

‘s

Pietà

.

Marian feasts

The earliest feasts that relate to Mary grew out of the cycle of feasts that

celebrated the

Nativity of Jesus

. Given that according to the

Gospel of Luke

(Luke

2:22-40), forty days after the birth of Jesus, along with the

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple

Mary was purified according to Jewish

customs, the Feast of the Purification began to be celebrated by the 5th

century, and became the “Feast of

Simeon

” in

Byzantium

.

Village decorations during the

Feast of the Assumption

in

Għaxaq

,

Malta.

In the 7th and 8th centuries four more Marian feasts were established in the

Eastern Church

. In the

Western Church

a feast dedicated to Mary, just before Christmas was

celebrated in the Churches of

Milan

and

Ravenna

in

Italy in the 7th century. The four Roman Marian feasts of Purification,

Annunciation, Assumption and Nativity of Mary were gradually and sporadically

introduced into England by the 11th century.

Over time, the number and nature of feasts (and the associated

Titles of Mary

) and the venerative practices that accompany them have varied

a great deal among diverse Christian traditions. Overall, there are

significantly more titles, feasts and venerative Marian practices among

Roman Catholics

than any other Christians traditions.

Some such feasts relate to specific events, e.g. the Feast of

Our Lady of Victory

was based on the 1571 victory of the

Papal

States

in the

Battle of Lepanto

.

Differences in feasts may also originate from doctrinal issues – the

Feast of the Assumption

is such an example. Given that there is no agreement

among all Christians on the circumstances of the death,

Dormition

or

Assumption of Mary

, the feast of assumption is celebrated among some

denominations and not others.

While the

Catholic Church

celebrates the Feast of the Assumption on August 15, some

Eastern Catholics

celebrate it as

Dormition of the Theotokos

, and may do so on August 28, if they follow the

Julian calendar

. The

Eastern Orthodox

also celebrate it as the

Dormition of the Theotokos

, one of their 12

Great Feasts

. Protestants do not celebrate this, or any other Marian feasts.

Christian doctrines

There is significant diversity in the Marian doctrines accepted by various

Christian churches. The key Marian doctrines held in Christianity can be briefly

outlined as follows:

The acceptance of these Marian doctrines by Christians can be summarized as

follows:

| Doctrine |

Church action |

Accepted by |

|

Mother of God

|

First Council of Ephesus

, 431 |

Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists,

|

|

Virgin birth of Jesus

|

First Council of Nicaea

, 325 |

Roman Catholics

,

Eastern Orthodox

,

Anglicans

,

Lutherans

,

Protestants

,

Latter Day Saints

|

|

Assumption of Mary

|

Munificentissimus Deus

encyclical

Pope Pius XII

, 1950 |

Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, some Anglicans, some Lutherans |

|

Immaculate Conception

|

Ineffabilis Deus

encyclical

Pope Pius IX

, 1854 |

Roman Catholics, some Anglicans, some Lutherans, early Martin Luther |

|

Perpetual Virginity

|

Council of Constantinople

, 533

Smalcald Articles

, 1537 |

Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Some Anglicans, Some Lutherans,

Martin Luther

,

John Wesley

|

The title “Mother of God” (Theotokos)

for Mary was confirmed by the

First Council of Ephesus

, held at the

Church of Mary

in 431. The Council decreed that Mary is the Mother of God

because her son Jesus is one person who is both God and man, divine and human.

This doctrine is widely accepted by Christians in general, and the term Mother

of God had already been used within the oldest known prayer to Mary, the

Sub tuum praesidium

which dates to around 250 AD.

The

Virgin birth of Jesus

has been a universally held belief among Christians

since the 2nd century,

It is included in the two most widely used

Christian

creeds

,

which state that Jesus “was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin

Mary” (the

Nicene

Creed

in what is now its familiar form)

and the

Apostles’ Creed

. The

Gospel of Matthew

describes Mary as a virgin who fulfilled the prophecy of

Isaiah 7:14

. The authors of the Gospels of Matthew and

Luke

consider Jesus’ conception not the result of intercourse and assert

that Mary had “no relations with man” before Jesus’ birth.

This alludes to the belief that Mary conceived Jesus through the action of God

the Holy Spirit, and not through

intercourse

with Joseph or anyone else.

The doctrines of the

Assumption

or

Dormition

of Mary relate to her death and bodily assumption to

Heaven

. While

the

Roman Catholic Church

has established the

dogma

of the Assumption, namely that Mary went directly to Heaven without a

usual physical death, the

Eastern Orthodox Church

believes in the Dormition, i.e. that she fell

asleep, surrounded by the Apostles.

Roman Catholics believe in the

Immaculate Conception of Mary

, as proclaimed

Ex Cathedra

by Pope

Pius IX

in 1854, namely that she was filled with grace from the very moment

of her conception in her mother’s womb and preserved from the stain of original

sin. The

Latin Rite

of the

Roman Catholic Church

has a liturgical

feast by that name

, kept on 8 December.

The

Eastern Orthodox

reject the Immaculate Conception principally because their

understanding of ancestral sin (the Greek term corresponding to the Latin

“original sin”) differs from that of the Roman Catholic Church.

The

Perpetual Virginity

of Mary, asserts Mary’s real and perpetual

virginity

even in the act of giving birth to the Son of God made Man. The term Ever-Virgin

(Greek ἀειπάρθενος) is applied in

this case, stating that Mary remained a virgin for the remainder of her life,

making Jesus her biological and only son, whose

conception

and

birth

are held to be miraculous.

Perspectives on Mary

|

Blessed Virgin Mary |

Annunciation

,

Philippe de Champaigne

, 1644 |

West:

Mother of God

,

Queen of Heaven

,

Mother of the Church

East: Theotokos

|

| Honored in |

Catholicism

,

Eastern Orthodoxy

,

Oriental Orthodoxy

,

Anglicanism

,

Lutheranism

|

|

Canonized

|

Pre-Congregation

|

Major

shrine

|

Santa Maria Maggiore

(See

Marian shrines

) |

|

Feast

|

See

Marian feast days

|

|

Attributes

|

Blue mantle, crown of 12 stars, pregnant woman, roses,

woman with child |

|

Patronage

|

See

Patronage of the Blessed Virgin Mary

|

Christian

perspectives on Mary

Christian Marian perspectives include a great deal of diversity. While some

Christians such as Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox have well established

Marian traditions, Protestants at large pay scant attention to Mariological

themes.

Roman Catholic

,

Eastern Orthodox

,

Oriental Orthodox

,

Anglican

,

and Lutherans

venerate

the Virgin Mary. This veneration especially takes the form of

prayer

for

intercession with her Son, Jesus Christ. Additionally it includes composing

poems and songs in Mary’s honor, painting icons or carving statues of her, and

conferring titles on Mary that reflect her position among the saints.

Anglican view

The multiple churches that form the

Anglican Communion

and the

Continuing Anglican

movement have different views on Marian doctrines and

venerative practices given that there is no single church with universal

authority within the Communion and that the mother church (the

Church of England

) understands itself to be both “catholic” and “Reformed“.

Thus unlike the Protestant churches at large, the Anglican Communion (which

includes the

Episcopal Church

in the United States) includes segments which still retain

some veneration of Mary.

Mary’s special position within God’s purpose of salvation as “God-bearer”

(Theotokos)

is recognised in a number of ways by some Anglican Christians.[99]

All the member churches of the Anglican Communion affirm in the historic creeds

that Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary, and celebrates the feast days of the

Presentation of Christ in the Temple

. This feast is called in older

prayer books

the

Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary

on 2 February. The

Annunciation

of our Lord to the Blessed Virgin on March 25 was from before

the time of Bede

until the 18th century New Year’s Day in England. The Annunciation is called the

“Annunciation of our Lady” in the 1662

Book of Common Prayer

. Anglicans also celebrate in the

Visitation of the Blessed Virgin

on May 31, though in some provinces the

traditional date of July 2 is kept. The feast of the St. Mary the Virgin is

observed on the traditional day of the Assumption, August 15. The

Nativity

of the Blessed Virgin is kept on September 8.

The Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary is kept in the 1662 Book of Common

Prayer, on December 8. In certain

Anglo-Catholic

parishes this feast is called the

Immaculate Conception

. Again, the

Assumption of Mary

is believed in by most Anglo-Catholics, but is considered

a pious

opinion by moderate Anglicans. Protestant minded Anglicans reject the

celebration of these feasts.

Prayers and venerative practices vary a great deal. For instance, as of the

19th century, following the

Oxford Movement

,

Anglo-Catholics

frequently pray the

Rosary

, the

Angelus

,

Regina Caeli

, and other litanies and anthems of Our Lady that are

reminiscent of Catholic practices.

On the other hand,

Low-church

Anglicans rarely invoke the Blessed Virgin except in certain hymns, such as the

second stanza of

Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones

.

The

Anglican Society of Mary

was formed in 1931 and maintains chapters in many

countries. The purpose of the society is to foster devotion to Mary among

Anglicans.The high-church

Anglicans espouse doctrines that are closer to Roman Catholics,

and retain veneration for Mary, e.g. official Anglican pilgrimages to

Our Lady of Lourdes

have taken place since 1963, and pilgrimages to

Our Lady of Walsingham

have gone on for hundreds of years.

Historically, there has been enough common ground between Roman Catholics and

Anglicans on Marian issues that in 2005 a joint statement called Mary: grace

and hope in Christ was produced through ecumenical meetings of Anglicans and

Roman Catholic theologians. This document, informally known as the “Seattle

Statement”, is not formally endorsed by either the Catholic Church or the

Anglican Communion, but is viewed by its authors as the beginning of a joint

understanding of Mary.

Catholic view

Madonna of humility

by

Domenico di Bartolo

, 1433; one of the most innovative

Marian images

from the early

Renaissance

.

In the

Catholic Church

, Mary is accorded the title “Blessed,” (from

Latin

beatus,

blessed, via

Greek

μακάριος, makarios and Latin facere, make) in

recognition of her

ascension

to Heaven and her capacity to intercede on behalf of those who

pray to her. Catholic teachings make clear that Mary is not considered divine

and prayers to her are not answered by her, they are answered by God.[106]

The

four Catholic dogmas

regarding Mary are:

Mother of God

,

Perpetual virginity of Mary

,

Immaculate Conception

(of Mary) and

Assumption of Mary.

The

Blessed Virgin Mary

, the mother of Jesus has a more central role in

Roman Catholic teachings and beliefs than in any other major Christian group.

Not only do Roman Catholics have more theological doctrines and teachings that

relate to Mary, but they have more festivals, prayers, devotional, and

venerative practices than any other group.

The

Catholic Catechism

states: “The Church’s devotion to the Blessed Virgin is

intrinsic to Christian worship.”

For centuries, Roman Catholics have performed acts of

consecration and entrustment to Mary

at personal, societal and regional

levels. These acts may be directed to the Virgin herself, to the

Immaculate Heart of Mary

and to the

Immaculata

. In Catholic teachings, consecration to Mary does not diminish or

substitute the love of God, but enhances it, for all consecration is ultimately

made to God.

Following the growth of Marian devotions in the 16th century, Catholic saints

wrote books such as

Glories of Mary

and

True Devotion to Mary

that emphasized Marian veneration and taught that “the

path to Jesus is through Mary”.

Marian devotions are at times linked to

Christocentric

devotions, e.g. the

Alliance of the Hearts of Jesus and Mary

.[113]

The chapel based on the claimed

House of Mary

in Ephesus

Key Marian devotions include:

Seven Sorrows of Mary

,

Rosary and scapular

,

Miraculous Medal

and

Reparations to Mary

.

The months of May and October are traditionally “Marian months” for Roman

Catholics, e.g. the daily

Rosary

is

encouraged in October and in

May Marian devotions

take place in many regions.

Popes have issued a number of

Marian encyclicals and Apostolic Letters

to encourage devotions to and the

veneration of the Virgin Mary.

Catholics place high emphasis on Mary’s roles as protector and intercessor

and the

Catholic Catechism

refers to Mary as the

“Mother of God to whose protection the faithful fly in all their dangers and

needs”

Key Marian prayers include:

Hail Mary

,

Alma Redemptoris Mater

,

Sub Tuum Praesidum

,

Ave Maris Stella

,

Regina

Coeli

,

Ave Regina Coelorum

and the

Magnificat

.

Mary’s participation in the processes of

salvation

and redemption has also been emphasized in the Catholic tradition,

but they are not doctrines.[125][126][127][128]

Pope John Paul II

‘s 1987 encyclical

Redemptoris Mater

began with the sentence: “The Mother of the Redeemer

has a precise place in the plan of salvation.”

In the 20th century both popes John Paul II and

Benedict XVI

have emphasized the Marian focus of the Church. Cardinal

Joseph Ratzinger

(later Pope Benedict XVI) wrote:

It is necessary to go back to Mary if we want to return to that “truth

about Jesus Christ,” “truth about the Church” and “truth about man”.

when he suggested a redirection of the whole Church towards the program of

Pope John Paul II in order to ensure an authentic approach to

Christology

via a return to the “whole truth about Mary”.

Orthodox view

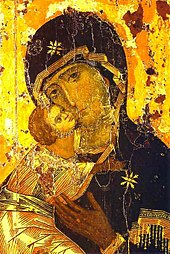

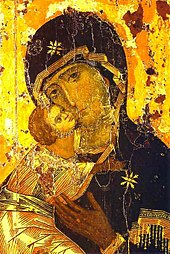

Our Lady of Vladimir

, one of the holiest medieval

representations of the

Theotokos

Orthodox Christianity

includes a large number of traditions regarding the

Ever Virgin Mary, the

Theotokos

.

The Orthodox believe that she was and remained a virgin before and after

Christ’s birth.

The

Theotokia

(i.e.

hymns

to the Theotokos

) are an essential part of the

Divine Services

in the

Eastern Church

and their positioning within the liturgical sequence

effectively places the Theotokos in the most prominent place after Christ.

Within the Orthodox tradition, the order of the saints begins with: The

Theotokos, Angels, Prophets, Apostles, Fathers, Martyres, etc. giving the Virgin

Mary precedence over the angels. She is also proclaimed as the “Lady of the

Angels”.

The views of the

Church Fathers

still play an important role in the shaping of Orthodox

Marian perspective. However, the Orthodox views on Mary are mostly

doxological

,

rather than academic: they are expressed in hymns, praise, liturgical poetry and

the veneration of icons. One of the most loved Orthodox

Akathists

(i.e.

standing hymns

) is devoted to Mary and it is often simply called the

Akathist Hymn

.

Five of the twelve

Great Feasts

in Orthodoxy are dedicated to Mary.The

Sunday of Orthodoxy

directly links the Virgin Mary’s identity as Mother of

God with icon veneration.

A number of Orthodox feasts are connected with the miraculous icons of the

Theotokos.

The Orthodox view Mary as “superior to all created beings”, although not

divine.

The Orthodox venerate Mary as conceived immaculate and assumed into heaven, but

they do not accept the Roman Catholic dogmas on these doctrines.

The Orthodox celebrate the

Dormition of the Theotokos

, rather than Assumption.

The

Protoevangelium of James

, an

extra-canonical

book, has been the source of many Orthodox beliefs on Mary.

The account of Mary’s life presented includes her consecration as a virgin at

the temple at age three. The

High Priest

Zachariah blessed Mary and informed her that God had magnified her name among

many generations. Zachariah placed Mary on the third step of the altar, whereby

God gave her grace. While in the temple, Mary was miraculously fed by an angel,

until she was twelve years old. At that point an angel told Zachariah to betroth

Mary to a widower in Israel, who would be indicated. This story provides the

theme of many hymns for the Feast of

Presentation of Mary

, and icons of the feast depict the story.

The Orthodox believe that Mary was instrumental in the growth of Christianity

during the life of Jesus, and after his Crucifixion, and Orthodox Theologian

Sergei Bulgakov

wrote: “The Virgin Mary is the center, invisible, but real,

of the Apostolic Church”

Theologians from the Orthodox tradition have made prominent contributions to

the development of Marian thought and devotion.

John Damascene

(c 650─c 750) was one of the greatest Orthodox theologians.

Among other Marian writings, he proclaimed the essential nature of Mary’s

heavenly Assumption or Dormition and her mediative role.

It was necessary that the body of the one who preserved her virginity

intact in giving birth should also be kept incorrupt after death. It was

necessary that she, who carried the Creator in her womb when he was a baby,

should dwell among the tabernacles of heaven.

From her we have harvested the grape of life; from her we have cultivated

the seed of immortality. For our sake she became Mediatrix of all blessings;

in her God became man, and man became God.

More recently,

Sergei Bulgakov

expressed the Orthodox sentiments towards Mary as follows:

Mary is not merely the instrument, but the direct positive condition of

the Incarnation, its human aspect. Christ could not have been incarnate by

some mechanical process, violating human nature. It was necessary for that

nature itself to say for itself, by the mouth of the most pure human being:

“Behold the handmaid of the Lord, be it unto me according to Thy word.”

Protestant view

Protestants in general reject the veneration and invocation of the Saints.

Protestants typically hold that Mary was the mother of Jesus, but was an

ordinary woman devoted to God. Therefore, there is virtually no Marian

veneration, Marian feasts, Marian pilgrimages, Marian art, Marian music or

Marian spirituality in today’s Protestant communities. Within these views, Roman

Catholic beliefs and practices are at times rejected, e.g., theologian

Karl Barth

wrote that “the heresy of the Catholic Church is its

Mariology

“.

Some early Protestants venerated and honored Mary.

Martin Luther

wrote that: “Mary is full of grace, proclaimed to be entirely

without sin. God’s grace fills her with everything good and makes her devoid of

all evil”.

However, as of 1532 Luther stopped celebrating the feast of the

Assumption of Mary

and also discontinued his support of the

Immaculate Conception

.

In the text of the

Magnificat

(recorded in

Luke 1:46-55

), Mary proclaims “My soul rejoices in God my Savior”.

The personal need of a savior is seen by Protestants as expressing that Mary

never thought herself “sinnless”.

John

Calvin

said, “It cannot be denied that God in choosing and destining Mary to

be the Mother of his Son, granted her the highest honor.

However, Calvin firmly rejected the notion that anyone but Christ can intercede

for man.

Although Calvin and

Huldrych Zwingli

honored Mary as the Mother of God in the 16th century, they

did so less than Martin Luther.

Thus the idea of respect and high honor for Mary was not rejected by the first

Protestants; but, they came to criticize the Roman Catholics for venerating

Mary. Following the

Council of Trent

in the 16th century, as Marian veneration became associated

with Catholics, Protestant interest in Mary decreased. During the Age of the

Enlightenment any residual interest in Mary within Protestant churches almost

disappeared, although Anglicans and Lutherans continued to honor her.

Protestants acknowledge that Mary is “blessed among women”

but they do not agree that Mary is to be venerated. She is considered to be an

outstanding example of a life dedicated to God.

In the 20th century, Protestants reacted in opposition to the Catholic dogma

of the

Assumption of Mary

. The conservative tone of the

Second Vatican Council

began to mend the ecumenical differences, and

Protestants began to show interest in Marian themes. In 1997 and 1998 ecumenical

dialogs between Catholics and Protestants took place, but to date the majority

of Protestants pay scant attention to Marian issues and often view them as a

challenge to the

authority of Scripture

.

Lutheran view

Stained glass of

Jesus leaving his mother

in a

Lutheran Church

, South Carolina.

Despite

Martin Luther

‘s harsh polemics against his Roman Catholic opponents over

issues concerning Mary and the saints, theologians appear to agree that Luther

adhered to the Marian decrees of the

ecumenical councils

and dogmas of the church. He held fast to the belief

that Mary was a perpetual virgin and the

Theotokos

or

Mother of God

.[145][146]

Special attention is given to the assertion that Luther, some three-hundred

years before the dogmatization of the

Immaculate Conception

by

Pope

Pius IX

in 1854, was a firm adherent of that view. Others maintain that

Luther in later years changed his position on the Immaculate Conception, which,

at that time was undefined in the Church, maintaining however the sinlessness of

Mary throughout her life.

For Luther, early in his life, the

Assumption of Mary

was an understood fact, although he later stated that the

Bible

did not say

anything about it and stopped celebrating its feast. Important to him was the

belief that Mary and the saints do live on after death.

“Throughout his career as a priest-professor-reformer, Luther preached, taught,

and argued about the veneration of Mary with a verbosity that ranged from

childlike piety to sophisticated polemics. His views are intimately linked to

his Christocentric theology and its consequences for liturgy and piety.”

Luther, while revering Mary, came to criticize the “Papists” for blurring the

line, between high admiration of the grace of God wherever it is seen in a human

being, and religious service given to another creature. He considered the Roman

Catholic practice of celebrating

saints

‘ days and

making intercessory requests addressed especially to Mary and other departed

saints to be idolatry

.

His final thoughts on Marian devotion and veneration are preserved in a sermon

preached at Wittenberg only a month before his death:

Therefore, when we preach faith, that we should worship nothing but God

alone, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, as we say in the Creed: ‘I

believe in God the Father almighty and in Jesus Christ,’ then we are

remaining in the temple at Jerusalem. Again,’This is my beloved Son;

listen to him.’ ‘You will find him in a manger’. He alone does it. But

reason says the opposite:

“What, us? Are we to worship only Christ? Indeed, shouldn’t we also

honor the holy mother of Christ? She is the woman who bruised the head

of the serpent. Hear us, Mary, for thy Son so honors thee that he can

refuse thee nothing. Here

Bernard

went too far in his Homilies on the Gospel: Missus est

Angelus.[155]

God has commanded that we should honor the parents; therefore I will

call upon Mary. She will intercede for me with the Son, and the Son with

the Father, who will listen to the Son. So you have the picture of God

as angry and Christ as judge; Mary shows to Christ her breast and Christ

shows his wounds to the wrathful Father. That’s the kind of thing this

comely bride, the wisdom of reason cooks up: Mary is the mother of

Christ, surely Christ will listen to her; Christ is a stern judge,

therefore I will call upon St. George and St. Christopher. No, we have

been by God’s command baptized in the name of the Father, the Son, and

the Holy Spirit, just as the Jews were circumcised.[156][157]

Certain Lutheran churches such as the

Anglo-Lutheran Catholic Church

however, continue to venerate Mary and the

saints in the same manner that Roman Catholics do, and hold all Marian dogmas as

part of their faith.

Methodist view

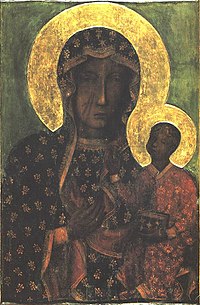

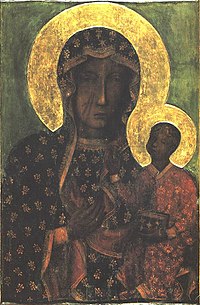

The

Black Madonna of Częstochowa

, Poland.

The

United Methodist Church

, as well as other

Methodist

churches, have no official writings or teachings on the Virgin Mary except what

is mentioned in Scripture and the ecumenical Creeds, mainly that Christ was

conceived

in her womb through the

Holy Spirit

and that she gave birth to

Christ

as a

virgin

.

John

Wesley

, the founder of the Methodist Movement within the

Church of England

, which later led to the

Methodist Church

, believed that the Virgin Mary was a

perpetual virgin

, meaning she never had sex.[159][160]

Many Methodists reject this concept, but some Methodists believe it. The church

does hold that Mary was a virgin before, during, and immediately after the birth

of Christ.

John Wesley stated in a letter to a Roman Catholic friend that:

“The Blessed Virgin Mary, who, as well after as when she brought him

forth, continued a pure and unspotted virgin.”

Article II of the Articles of Religion of the Methodist Church states that:

The Son, who is the Word of the Father, the very and eternal God, of one

substance with the Father, took man’s nature in the womb of the blessed

Virgin; so that two whole and perfect natures, that is to say, the

Godhead and Manhood, were joined together in one person, never to be

divided; whereof is one Christ, very God and very Man, who truly

suffered, was crucified, dead, and buried, to reconcile his Father to

us, and to be a sacrifice, not only for original guilt, but also for

actual sins of men.

From this, the Virgin Mary is believed to be the

Theotokos

,

or Mother of God, in the Methodist Church, although the term is usually only

used by those of

High Church

and

Evangelical Catholic

tradition.

Article II of The Confession of Faith from The Book of Discipline states:

“We believe in Jesus Christ, truly God and truly man, in whom the divine

and human natures are perfectly and inseparably united. He is the

eternal Word made flesh, the only begotten Son of the Father, born of

the Virgin Mary by the power of the Holy Spirit. As ministering servant

he lived, suffered and died on the cross. He was buried, rose from the

dead and ascended into heaven to be with the Father, from whence he

shall return. He is eternal Savior and Mediator, who intercedes for us,

and by him all persons are to be judged.”

From this statement, Methodists reject the Catholic ideas of Mary as a

Co-Redemptrix

and Mediatrix

of the Faith. The Methodist Churches disagree with

veneration of saints

, of Mary, and of relics; believing that reverence and

praise are for God alone. However, studying the life of Mary and the biographies

of saints is deemed appropriate, as they are seen as heroes and examples of good

Christians.

The Methodist churches reject the doctrines of the

Immaculate Conception

and the

Assumption of Mary

, stating that Christ was the only person to live a

sinless life and to ascend body and soul into Heaven.

Latter Day Saints

In the first edition of the Book of Mormon (1830), Mary was referred to as

“the mother of God, after the manner of the flesh,” a reading that was changed

to “the mother of the Son of God” in all subsequent editions (1837–).

Nontrinitarian view

Nontrinitarians

, such as

Unitarians

,

Christadelphians

and

Jehovah’s Witnesses

consider Mary as the mother of

Jesus Christ

. Because they do not consider Jesus as God, they do not

consider Mary as the Mother of God or the Theotokos. Since Nontrinitarian

churches are typically also

mortalist

, the issue of praying to Mary, whom they would consider “asleep,”

awaiting resurrection, does not arise.

Swedenborg

says God as he is in himself could not directly approach evil

spirits to redeem those spirits without destroying them (Exodus 33:20, John

1:18), so God impregnated Mary, who gave Jesus Christ access to the evil

heredity of the human race, which he could approach, redeem and save.

Islamic perspective

Mary, the mother of Jesus, is mentioned as Maryam, more in the

Qur’an

than in the entire

New

Testament

.[169][170]

She enjoys a singularly distinguished and honored position among

women in the Qur’an

. A

Sura (chapter) in

the Qur’an is titled “Maryam”

(Mary), which is the only Sura in the Qur’an named after a woman, in which the

story of Mary (Maryam) and Jesus (Isa)

is recounted according to the Islamic view of Jesus.

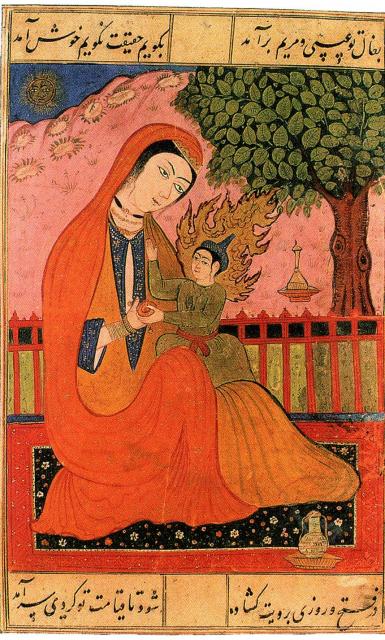

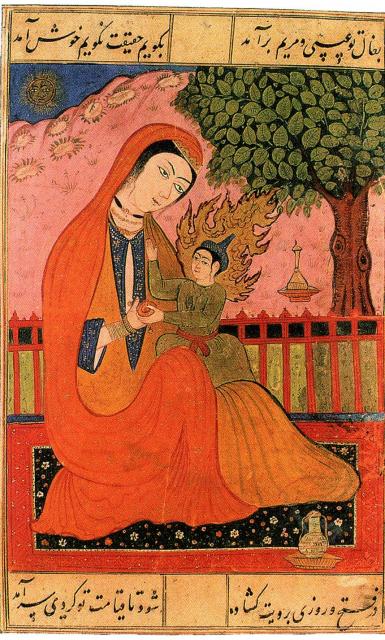

Maryam (Mary) with her son Isa (Jesus), Persian miniature.

She is mentioned in the

Qur’an

with the honorific title of “our lady” (syyidatuna) as the

daughter of Imran and Hannah.

She is the only woman directly named in the Qur’an; declared (uniquely along

with Jesus) to be a Sign of God to mankind;

as one who “guarded her chastity“;

an obedient one;[]

chosen of her mother and dedicated to God whilst still in the womb;

uniquely (amongst women) Accepted into service by God;cared for by (one of the prophets as per Islam)

Zakariya

(Zacharias);

that in her childhood she resided in the Temple and uniquely had access to Al-Mihrab

(understood to be the

Holy of Holies

), and was provided with heavenly ‘provisions’ by God.

Mary is also called a Chosen One a Purified One;]

a Truthful one;

her child conceived through “a Word from God”;

and “exalted above all women of The Worlds/Universes (the material and

heavenly worlds)”.

The Qur’an relates detailed narrative accounts of Maryam (Mary) in two places

Sura 3

and Sura 19

These state beliefs in both the Immaculate Conception of Mary and the Virgin

birth of Jesus. The account given in Sura 19

of the Qur’an is nearly identical with that in the Gospel according to

Luke

, and both of these (Luke, Sura 19) begin with an account of the

visitation of an angel upon Zakariya (Zecharias) and Good News of the birth

of Yahya (John), followed by the account of the annunciation. It mentions

how Mary was informed by an angel that she would become the mother of Jesus

through the actions of God alone.

In the Islamic tradition, Mary and Jesus were the only children who could not

be touched by Satan at the moment of their birth, for God imposed a veil between

them and Satan.

According to author Shabbir Akhtar, the Islamic perspective on Mary’s Immaculate

Conception is compatible with the Catholic doctrine of the same topic

The Qur’an says that Jesus was the result of a virgin birth. The most

detailed account of the annunciation and birth of Jesus is provided in Sura 3

and 19 of The Qur’an wherein it is written that God sent an angel to announce

that she could shortly expect to bear a son, despite being a virgin.

Other views

Pagan Rome

From the early stages of Christianity, belief in the virginity of Mary and

the virgin conception of Jesus, as stated in the gospels, holy and supernatural,

was used by detractors, both political and religious, as a topic for

discussions, debates and writings, specifically aimed to challenge the divinity

of Jesus and thus Christians and Christianity alike.

In the 2nd century, as part of the earliest anti-Christian polemics,

Celsus

suggested that Jesus was the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier named Panthera.

The views of Celsus drew responses from

Origen

, the

Church Father in

Alexandria, Egypt

who considered it a fabricated story.

How far Celsus sourced his view from Jewish sources remains a subject of

discussion.

In Judaism

The issue of the parentage of

Jesus in the Talmud

affects also the view of his mother. However the Talmud

does not mention Mary by name and is considerate rather than only polemic.

The story about Panthera is also found the

Toledot Yeshu

, the literary origins of which can not be traced with any

certainty and given that it is unlikely to go before the 4th century, it is far

too late to include authentic remembrances of Jesus.

The Blackwell Companion to Jesus states that the Toledot Yeshu has no historical

facts as such, and was perhaps created as a tool for warding off conversions to

Christianity.

The name Panthera may be a distortion of the term parthenos (virgin) and

Raymond E. Brown

considers the story of Panthera a fanciful explanation of

the birth of Jesus which includes very little historical evidence.

Robert Van Voorst

states that given that Toledot Yeshu is a medieval

document and due to its lack of a fixed form and orientation towards a popular

audience, it is “most unlikely” to have reliable historical information.

4th-century Arabia

According to the 4th century heresiologist

Epiphanius of Salamis

the Virgin Mary was worshipped as a

Mother goddess

in the heretical Christian sect

Collyridianism

, which was found throughout Arabia sometime during the 300s

AD. Collyridianism was made up mostly of women and even had women priests. They

were known to make bread offerings to the Virgin Mary, along with other

practices. The group was condemned as heretical by the

Roman Catholic Church

and was preached against by

Epiphanius of Salamis

, who wrote about the group in his writings titled

Panarion

.

Study of the

historical Jesus

To date, scholars continue to debate the accounts of the birth of Jesus from

several perspectives, including textual analysis, historical records and

post-apostolic witnesses.

Bart D. Ehrman

has suggested that the

historical method

can never comment on the likelihood of supernatural

occurrences (meaning that miracles can never be considered historical facts).

The statement in

Matthew 1:25

that “Joseph did not know Mary until she has given birth to a

son” has been debated among scholars, some suggesting that she did not remain

perpetually virgin

. Other scholars contend that the Greek word hoes (i.e.