|

Manuel I , Comnenus – Byzantine Emperor: 8 April 1143 – 24

September 1180 A.D. –

Bronze Half Tetarteron 16mm (1.78 grams) Struck at Uncertain Greek Mint

circa 1143-1180 A.D.

Reference: Sear 1980

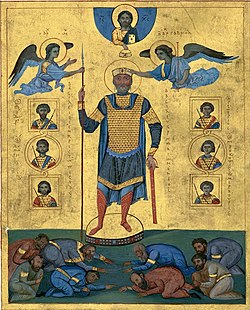

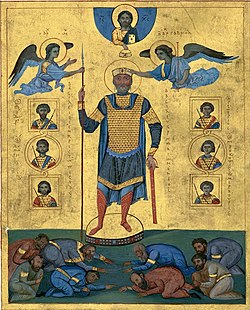

Bust of St. George facing, beardless, wearing nimbus, tunic, cuirass and sagion,

and holding spear

and shield; to left, Θ / Γ / Є; to right, WP / ΓI / O / C.

MANYHΛ ΔΕCΠΟΤ, Bust of Manuel facing, wearing crown and loros, and holding

labarum and globe

topped with a cross.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

Comnenus , or

Manuel

I Komnenos (Greek:

Μανουήλ Α’ Κομνηνός, Manouēl I

Komnēnos,

November

28

, 1118

–

September 24

,

1180) was a

Byzantine Emperor

of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning

point in the history of

Byzantium

and the

Mediterranean

. Eager to restore his

empire

to its past glories as the superpower of the Mediterranean world,

Manuel pursued an energetic and ambitious foreign policy. In the process he made

alliances with the Pope

and the resurgent west, invaded

Italy

, successfully handled the passage of the dangerous

Second Crusade

through his empire, and established a Byzantine protectorate

over the

Crusader kingdoms

of

Outremer

.

Facing Muslim

advances in the

Holy Land

,

he made common cause with the

Kingdom of Jerusalem

and participated in a combined invasion of

Fatimid

Egypt

.

Manuel reshaped the political maps of the

Balkans

and

the east Mediterranean, placing the kingdoms of

Hungary

and Outremer under Byzantine

hegemony

and campaigning aggressively against his neighbours both in the west and in the

east. However, towards the end of his reign Manuel’s achievements in the east

were compromised by a serious defeat at

Myriokephalon

, which in large part resulted from his arrogance in attacking

a well-defended

Seljuk

position.

Called ho Megas (Greek:

ὁ Μέγας, translated as “the

Great“) by the Greeks

, Manuel is known to have inspired intense loyalty in those who served

him. He also appears as the hero of a history written by his secretary,

John

Kinnamos

, in which every virtue is attributed to him. Manuel, who was

influenced by his contact with western Crusaders, enjoyed the reputation of “the

most blessed emperor of

Constantinople

” in parts of the

Latin

world as

well.[1]

Modern historians, however, have been less enthusiastic about him. Some of them

assert that the great power he wielded was not his own personal achievement, but

that of the

dynasty

he represented; they also argue that, since Byzantine imperial power

declined so rapidly after Manuel’s death, it is only natural to look for the

causes of this decline in his reign.

Labarum of Constantine I, displaying the “Chi-Rho” symbol above.

The labarum was a

vexillum

(military standard) that displayed

the “Chi-Rho”

symbol

☧

, formed from the first two

Greek letters

of the word “Christ”

—

Chi

and

Rho

. It was first used by the

Roman emperor

Constantine I

. Since the vexillum consisted of

a flag suspended from the crossbar of a cross, it was ideally suited to

symbolize the

crucifixion

of

Christ

.

Later usage has sometimes regarded the terms “labarum” and “Chi-Rho” as

synonyms. Ancient sources, however, draw an unambiguous distinction between the

two.

Etymology

Beyond its derivation from Latin labarum, the etymology of the word is

unclear. Some derive it from Latin /labāre/ ‘to totter, to waver’ (in the sense

of the “waving” of a flag in the breeze) or laureum [vexillum] (“laurel

standard”). According to the

Real Academia Española

, the related

lábaro

is also derived from Latin labărum

but offers no further derivation from within Latin, as does the Oxford English

Dictionary.[5]

An origin as a loan into Latin from a Celtic language or

Basque

has also been postulated. There is a

traditional Basque symbol called the

lauburu

; though the name is only attested from

the 19th century onwards the motif occurs in engravings dating as early as the

2nd century AD.

Vision of Constantine

A coin of Constantine (c.337) showing a depiction of his labarum

spearing a serpent.

On the evening of October 27, 312, with his army preparing for the

Battle of the Milvian Bridge

, the emperor

Constantine I

claimed to have had a vision

which led him to believe he was fighting under the protection of the

Christian God

.

Lactantius

states that, in the night before the

battle, Constantine was commanded in a dream to “delineate the heavenly sign on

the shields of his soldiers”. He obeyed and marked the shields with a sign

“denoting Christ”. Lactantius describes that sign as a “staurogram”, or a

Latin cross

with its upper end rounded in a

P-like fashion, rather than the better known

Chi-Rho

sign described by

Eusebius of Caesarea

. Thus, it had both the

form of a cross and the monogram of Christ’s name from the formed letters “X”

and “P”, the first letters of Christ’s name in Greek.

From Eusebius, two accounts of a battle survive. The first, shorter one in

the

Ecclesiastical History

leaves no doubt that

God helped Constantine but doesn’t mention any vision. In his later Life of

Constantine, Eusebius gives a detailed account of a vision and stresses that

he had heard the story from the emperor himself. According to this version,

Constantine with his army was marching somewhere (Eusebius doesn’t specify the

actual location of the event, but it clearly isn’t in the camp at Rome) when he

looked up to the sun and saw a cross of light above it, and with it the Greek

words

Ἐν Τούτῳ Νίκα

. The traditionally employed

Latin translation of the Greek is

in hoc signo vinces

— literally “In this

sign, you will conquer.” However, a direct translation from the original Greek

text of Eusebius into English gives the phrase “By this, conquer!”

At first he was unsure of the meaning of the apparition, but the following

night he had a dream in which Christ explained to him that he should use the

sign against his enemies. Eusebius then continues to describe the labarum, the

military standard used by Constantine in his later wars against

Licinius

, showing the Chi-Rho sign.

Those two accounts can hardly be reconciled with each other, though they have

been merged in popular notion into Constantine seeing the Chi-Rho sign on the

evening before the battle. Both authors agree that the sign was not readily

understandable as denoting Christ, which corresponds with the fact that there is

no certain evidence of the use of the letters chi and rho as a Christian sign

before Constantine. Its first appearance is on a Constantinian silver coin from

c. 317, which proves that Constantine did use the sign at that time, though not

very prominently. He made extensive use of the Chi-Rho and the labarum only

later in the conflict with Licinius.

The vision has been interpreted in a solar context (e.g. as a

solar halo

phenomenon), which would have been

reshaped to fit with the Christian beliefs of the later Constantine.

An alternate explanation of the intersecting celestial symbol has been

advanced by George Latura, which claims that Plato’s visible god in Timaeus

is in fact the intersection of the Milky Way and the Zodiacal Light, a rare

apparition important to pagan beliefs that Christian bishops reinvented as a

Christian symbol.

Eusebius’ description of the labarum

“A Description of the Standard of the Cross, which the Romans now call the

Labarum.” “Now it was made in the following manner. A long spear, overlaid with

gold, formed the figure of the cross by means of a transverse bar laid over it.

On the top of the whole was fixed a wreath of gold and precious stones; and

within this, the symbol of the Saviour’s name, two letters indicating the name

of Christ by means of its initial characters, the letter P being intersected by

X in its centre: and these letters the emperor was in the habit of wearing on

his helmet at a later period. From the cross-bar of the spear was suspended a

cloth, a royal piece, covered with a profuse embroidery of most brilliant

precious stones; and which, being also richly interlaced with gold, presented an

indescribable degree of beauty to the beholder. This banner was of a square

form, and the upright staff, whose lower section was of great length, of the

pious emperor and his children on its upper part, beneath the trophy of the

cross, and immediately above the embroidered banner.”

“The emperor constantly made use of this sign of salvation as a safeguard

against every adverse and hostile power, and commanded that others similar to it

should be carried at the head of all his armies.”

Iconographic career under Constantine

Coin of

Vetranio

, a soldier is holding two

labara. Interestingly they differ from the labarum of Constantine in

having the Chi-Rho depicted on the cloth rather than above it, and

in having their staves decorated with

phalerae

as were earlier Roman

military unit standards.

The emperor

Honorius

holding a variant of the

labarum – the Latin phrase on the cloth means “In the name of Christ

[rendered by the Greek letters XPI] be ever victorious.”

Among a number of standards depicted on the

Arch of Constantine

, which was erected, largely

with fragments from older monuments, just three years after the battle, the

labarum does not appear. A grand opportunity for just the kind of political

propaganda that the Arch otherwise was expressly built to present was missed.

That is if Eusebius’ oath-confirmed account of Constantine’s sudden,

vision-induced, conversion can be trusted. Many historians have argued that in

the early years after the battle the emperor had not yet decided to give clear

public support to Christianity, whether from a lack of personal faith or because

of fear of religious friction. The arch’s inscription does say that the Emperor

had saved the

res publica

INSTINCTV DIVINITATIS

MENTIS MAGNITVDINE (“by greatness of mind and by instinct [or impulse]

of divinity”). As with his predecessors, sun symbolism – interpreted as

representing

Sol Invictus

(the Unconquered Sun) or

Helios

,

Apollo

or

Mithras

– is inscribed on his coinage, but in

325 and thereafter the coinage ceases to be explicitly pagan, and Sol Invictus

disappears. In his

Historia Ecclesiae

Eusebius further reports

that, after his victorious entry into Rome, Constantine had a statue of himself

erected, “holding the sign of the Savior [the cross] in his right hand.” There

are no other reports to confirm such a monument.

Whether Constantine was the first

Christian

emperor supporting a peaceful

transition to Christianity during his rule, or an undecided pagan believer until

middle age, strongly influenced in his political-religious decisions by his

Christian mother

St. Helena

, is still in dispute among

historians.

As for the labarum itself, there is little evidence for its use before 317.In

the course of Constantine’s second war against Licinius in 324, the latter

developed a superstitious dread of Constantine’s standard. During the attack of

Constantine’s troops at the

Battle of Adrianople

the guard of the labarum

standard were directed to move it to any part of the field where his soldiers

seemed to be faltering. The appearance of this talismanic object appeared to

embolden Constantine’s troops and dismay those of Licinius.At the final battle

of the war, the

Battle of Chrysopolis

, Licinius, though

prominently displaying the images of Rome’s pagan pantheon on his own battle

line, forbade his troops from actively attacking the labarum, or even looking at

it directly.[16]

Constantine felt that both Licinius and

Arius

were agents of Satan, and associated them

with the serpent described in the

Book of Revelation

(12:9).

Constantine represented Licinius as a snake on his coins.

Eusebius stated that in addition to the singular labarum of Constantine,

other similar standards (labara) were issued to the Roman army. This is

confirmed by the two labara depicted being held by a soldier on a coin of

Vetranio

(illustrated) dating from 350.

Saint George (c. 275/281 – 23 April 303 AD) was a Greek who became an

officer in the Roman army. His father was the Greek Gerondios from

Cappadocia

Asia Minor and his mother was from

the city Lydda

.

Lydda

was a Greek city in

Palestine

from the times of the conquest of

Alexander the Great (333 BC). Saint George became an officer in the Roman army

in the Guard of

Diocletian

. He is venerated as a Christian

martyr. In

hagiography

, Saint George is one of the most

venerated saints in the

Catholic

(Western

and

Eastern Rites

),

Anglican

,

Eastern Orthodox

, and the

Oriental Orthodox

churches. He is immortalized

in the tale of

Saint George and the Dragon

and is one of the

Fourteen Holy Helpers

. His memorial is

celebrated on 23 April, and he is regarded as one of the most prominent

military saints

.

Many

Patronages of Saint George

exist around the

world, including:

Georgia

,

England

,

Egypt

,

Bulgaria

,

Aragon

,

Catalonia

,

Romania

,

Ethiopia

,

Greece

,

India

,

Iraq, Israel

,

Lebanon

,

Lithuania

,

Palestine

,

Portugal

,

Serbia

,

Ukraine

and

Russia

, as well as the cities of

Genoa

,

Amersfoort

,

Beirut

,

Botoşani

,

Drobeta Turnu-Severin

,

Timişoara

,

Fakiha

,

Bteghrine

,

Cáceres

,

Ferrara

,

Freiburg im Breisgau

,

Kragujevac

,

Kumanovo

,

Ljubljana

,

Pérouges

,

Pomorie

,

Preston

,

Qormi

,

Rio de Janeiro

,

Lod,

Lviv,

Barcelona

,

Moscow

and

Victoria, as well as of

the Scout Movement

[3]

and a wide range of professions, organizations and disease sufferers.

Life of Saint George

Historians have argued the exact details of the birth of Saint George for

over a century, although the approximate date of his death is subject to little

debate.[4][5]

The 1913

Catholic Encyclopedia

takes the position that

there seems to be no ground for doubting the historical existence of Saint

George, but that little faith can be placed in some of the fanciful stories

about him.[6]

The work of the

Bollandists

Danile Paperbroch

,

Jean Bolland

and

Godfrey Henschen

in the 17th century was one of

the first pieces of scholarly research to establish the historicity of the

saint’s existence via their publications in

Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca

and paved the

way for other scholars to dismiss the medieval legends.[7][8]

Pope Gelasius

stated that George was among

those saints “whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are

known only to God.”[9]

The traditional legends

have offered a historicised narration

of George’s encounter with a

dragon

: see “St. George and the Dragon” below.

The modern legend that follows below is synthesised from early and late

hagiographical sources

, omitting the more

fantastical episodes, to narrate a purely human military career in closer

harmony with modern expectations of reality. Chief among the legendary sources

about the saint is the

Golden Legend

, which remains the most familiar

version in English owing to

William Caxton

‘s 15th-century translation.[10]

It is likely that Saint George was born to a Greek Christian noble family in

Lydda, Palestine, during the late third century between about 275 AD and 285 AD,

and he died in the Greek city Nicomedia, Asia Minor. His father, Gerontios, was

a Greek, from Cappadocia, Asia Minor, officer in the Roman army and his mother,

Polychronia, was a Greek from the city Lydda, Palestine. They were both

Christians and from noble families of

Anici

, so the child was raised with Christian

beliefs. They decided to call him Georgios (Greek), meaning “worker of the land”

(i.e., farmer). At the age of 14, George lost his father; a few years later,

George’s mother, Polychronia, died.[11][12][13][14]

Eastern accounts give the names of his parents as Anastasius and Theobaste.[citation

needed]

Saint George Killing the Dragon, 1434/35, by

Martorell

Then George decided to go to

Nicomedia

, the imperial city of that time, and

present himself to Emperor

Diocletian

to apply for a career as a soldier.

Diocletian welcomed him with open arms, as he had known his father, Gerontius —

one of his finest soldiers. By his late 20s, George was promoted to the rank of

Tribunus

and stationed as an imperial guard of

the Emperor at Nicomedia.[15]

In the year AD 302, Diocletian (influenced by

Galerius

) issued an edict that every Christian

soldier in the army should be arrested and every other soldier should offer a

sacrifice to the

Roman gods

of the time. However George objected

and with the courage of his faith approached the Emperor and ruler. Diocletian

was upset, not wanting to lose his best

tribune

and the son of his best official,

Gerontius. George loudly renounced the Emperor’s edict, and in front of his

fellow soldiers and Tribunes he claimed himself to be a Christian and declared

his worship of Jesus Christ. Diocletian attempted to convert George, even

offering gifts of land, money and slaves if he made a sacrifice to the Roman

gods. The Emperor made many offers, but George never accepted.[16]

Recognizing the futility of his efforts, Diocletian was left with no choice

but to have him executed for his refusal. Before the execution George gave his

wealth to the poor and prepared himself. After various torture sessions,

including laceration on a wheel of swords in which he was resuscitated three

times, George was executed by

decapitation

before Nicomedia’s city wall, on

April 23, 303. A witness of his suffering convinced Empress Alexandra and

Athanasius, a pagan priest, to become Christians as well, and so they joined

George in martyrdom. His body was returned to

Lydda

in Palestine for burial, where Christians

soon came to honour him as a martyr.[17][18]:166

Although the above distillation of the legend of George connects him to the

conversion of Athanasius, who according to

Rufinus

was brought up by Christian

ecclesiastical authorities from a very early age,[19]

Edward Gibbon

[20][21]

argued that George, or at least the legend from which the above is distilled, is

based on

George of Cappadocia

,[22][23]

a notorious Arian bishop who was Athanasius’ most bitter rival, who in time

became Saint George of England. According to Professor Bury, Gibbon’s latest

editor, “this theory of Gibbon’s has nothing to be said for it.” He adds that:

“the connection of St. George with a dragon-slaying legend does not relegate him

to the region of the myth”.[24]

In 1856

Ralph Waldo Emerson

published a book of essays

entitled “English Traits.” In it, he wrote a paragraph on the history of Saint

George. Emerson compared the legend of Saint George to the legend of

Amerigo Vespucci

, calling the former “an

impostor” and the latter “a thief.”[25][26]

The editorial notes appended to the 1904 edition of Emerson’s complete works

state that Emerson based his account on the work of Gibbon, and that current

evidence seems to show that real St. George was not George the Arian of

Cappadocia.[25]

Merton M. Sealts also quotes

Edward Emerson

, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s youngest

son as stating that he believed his father’s account was derived from Gibbon and

that the real St. George “was apparently another who died two generations

earlier.”[27]

Saint George and

the dragon

Eastern Orthodox depictions of Saint George slaying a dragon often include

the image of the young maiden who looks on from a distance. The standard

iconographic interpretation of the image

icon is that the dragon represents both Satan (Rev. 12:9) and the

Roman Empire. The young maiden is the wife of

Diocletian

,

Alexandra

. Thus, the image as interpreted

through the language of Byzantine iconography, is an image of the martyrdom of

the saint.[citation

needed]

The episode of St. George and the

Dragon

was a legend[28]

brought back with the

Crusaders

and retold with the courtly

appurtenances belonging to the

genre of Romance

. The earliest known depiction

of the legend is from early eleventh-century

Cappadocia

(in the

iconography

of the

Eastern Orthodox Church

, George had been

depicted as a soldier

since at least the seventh century);

the earliest known surviving narrative text is an eleventh-century Georgian

text.

White George on the

coat of arms

of

Georgia

.

In the fully developed Western version, which developed as part of the

Golden Legend

, a dragon or

crocodile

makes its nest at the

spring

that provides water for the city of

“Silene” (perhaps modern

Cyrene

in

Libya

or the city of

Lydda in the

Holy Land

, depending on the source).

Consequently, the citizens have to dislodge the dragon from its nest for a time,

to collect water. To do so, each day they offer the dragon at first a sheep, and

if no sheep can be found, then a

maiden

must go instead of the sheep. The victim

is chosen by drawing lots. One day, this happens to be the

princess

. The

monarch

begs for her life to be spared, but to

no avail. She is offered to the dragon, but there appears Saint George on his

travels. He faces the dragon, protects himself with the

sign of the Cross

,[29]

slays the dragon, and rescues the princess. The citizens abandon their ancestral

paganism

and convert to Christianity.

The dragon motif was first combined with the standardised Passio Georgii

in

Vincent of Beauvais

‘ encyclopaedic Speculum

Historiale and then in

Jacobus de Voragine

‘s “Golden

Legend“, which guaranteed its popularity in the later

Middle Ages

as a literary and pictorial

subject.

The parallels with

Perseus

and

Andromeda

are inescapable. In the

allegorical

reading, the dragon embodies a

suppressed

pagan cult

.[30]

The story has other roots that predate Christianity. Examples such as

Sabazios

, the

sky father

, who was usually depicted riding on

horseback, and Zeus

‘s defeat of

Typhon

the

Titan

in

Greek mythology

, along with examples from

Germanic

and

Vedic traditions

, have led a number of

historians, such as Loomis, to suggest that George is a

Christianized

version of older deities in

Indo-European culture.

In the medieval romances, the lance with which St George slew the dragon was

called Ascalon, named after the city of

Ashkelon

in the

Levant

.[31]

Veneration as a martyr

A church built in Lydda

during the reign of

Constantine I

(reigned 306–37), was consecrated

to “a man of the highest distinction”, according to the church history of

Eusebius of Caesarea

; the name of the patron[32]

was not disclosed, but later he was asserted to have been George.

By the time of the Muslim conquest in the seventh century, a basilica

dedicated to the saint in Lydda existed.[33]

The church was destroyed in 1010 but was later rebuilt and dedicated to Saint

George by the

Crusaders

. In 1191 and during the conflict

known as the

Third Crusade

(1189–92), the church was again

destroyed by the forces of

Saladin

, Sultan of the

Ayyubid dynasty

(reigned 1171–93). A new church

was erected in 1872 and is still standing.

During the fourth century the veneration of George spread from Palestine

through Lebanon to the rest of the

Eastern Roman Empire

– though the martyr is not

mentioned in the Syriac

Breviarium

[18]

– and

Georgia

. In Georgia the feast day on November

23 is credited to

St Nino

of

Cappadocia

, who in Georgian hagiography is a

relative of St George, credited with bringing Christianity to the Georgians in

the fourth century. By the fifth century, the

cult

of Saint George had reached the

Western Roman Empire

as well: in 494, George

was canonized as a saint

by

Pope Gelasius I

, among those “whose names are

justly reverenced among men, but whose acts are known only to [God].”

In England the earliest dedication to George, who was mentioned among the

martyrs by Bede

, is a church at

Fordington

, Dorset, that is mentioned in the

wars of

Alfred the Great

. He did not rise to the

position of “patron saint”, however, until the 14th century, and he was still

obscured by

Edward the Confessor

, the traditional patron

saint of England, until 1552 when all saints’ banners other than George’s were

abolished in the

English Reformation

.

[34]

An apparition of George heartened the Franks at the

siege of Antioch

, 1098, and made a similar

appearance the following year at Jerusalem. Chivalric military

Order of St. George

were established in

Aragon

(1201),

Genoa

,

Hungary

, and by

Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor

,[35]

and in England the Synod of Oxford, 1222 declared

St George’s Day

a feast day in the kingdom of

England.

Edward III

put his

Order of the Garter

under the banner of St.

George, probably in 1348. The chronicler

Froissart

observed the English invoking St.

George as a battle cry on several occasions during the

Hundred Years’ War

. In his rise as a national

saint George was aided by the very fact that the saint had no legendary

connection with England, and no specifically localized shrine, as of

Thomas Becket

at Canterbury: “Consequently,

numerous shrines were established during the late fifteenth century,” Muriel C.

McClendon has written,[36]

“and his did not become closely identified with a particular occupation or with

the cure of a specific malady.”

The establishment of George as a popular saint and protective giant[37]

in the West that had captured the medieval imagination was codified by the

official elevation of his feast to a festum duplex[38]

at a church council in 1415, on the date that had become associated with his

martyrdom, 23 April. There was wide latitude from community to community in

celebration of the day across late medieval and early modern England,[39]

and no uniform “national” celebration elsewhere, a token of the popular and

vernacular nature of George’s cultus and its local horizons, supported by

a local guild

or confraternity under George’s

protection, or the dedication of a local church. When the Reformation in England

severely curtailed the saints’ days in the calendar, St. George’s Day was among

the holidays that continued to be observed.

Sources

The

coat of arms

of

Volodymyr

is the oldest known

Ukrainian city emblem.

According to the

Catholic Encyclopedia

, the earliest text

preserving fragments of George’s narrative is in an

Acta Sanctorum

identified by

Hippolyte Delehaye

of the scholarly

Bollandists

to be a

palimpsest

of the fifth century. However, this

Acta Sancti Georgii was soon banned as

heresy

by

Pope Gelasius I

(in 496).

The compiler of this Acta, according to Hippolyte Delehaye “confused

the martyr with his namesake, the celebrated

George of Cappadocia

, the

Arian

intruder into the see of Alexandria and

enemy of St.

Athanasius

“. A critical edition of a Syriac

Acta of Saint George, accompanied by an annotated English translation was

published by E.W. Brooks (1863–1955) in 1925. The hagiography was originally

written in Greek.

In Sweden, the princess rescued by Saint George is held to represent the

kingdom of Sweden, while the dragon represents an invading army. Several

sculptures of Saint George battling the dragon can be found in Stockholm, the

earliest inside Storkyrkan (“The Great Church”) in the Old Town.

The façade of architect

Antoni Gaudi

‘s famous

Casa Batlló

in

Barcelona, Spain

depicts this allegory.

In Islamic cultures

Saint George is somewhat of an exception among saints and legends, in that he

is known and respected by

Muslims

, as well as venerated by Christians

throughout the

Middle East

, from Egypt to Asia Minor.[40]

His stature in these regions derives from the fact that his figure has become

somewhat of a composite character mixing elements from Biblical, Quranic and

folkloric sources, at times being partially identified with

Al-Khidr

.[40]

He is said to have killed a dragon near the sea in

Beirut

and at the beginning of the 20th century

Muslim women used to visit his shrine in the area to pray for him.[40]

Feast days

In the General Calendar of the

Roman Rite

the feast of Saint George is on

April 23. In the

Tridentine Calendar

it was given the rank of

“Semidouble”. In

Pope Pius XII

‘s

1955 calendar

this rank is reduced to “Simple”.

In

Pope John XXIII

‘s

1960 calendar

the celebration is further

demoted to just a

“Commemoration”

. In

Pope Paul VI

‘s

1969 calendar

it is raised to the level of an

optional “Memorial”. In some countries, such as

England

, the rank is higher.

St George is very much honoured by the

Eastern Orthodox Church

, wherein he is referred

to as a “Great Martyr”, and in

Oriental Orthodoxy

overall. His major

feast day

is on April 23 (Julian

Calendar April 23 currently corresponds to

Gregorian Calendar

May 6). If, however, the

feast occurs before Easter

, it is celebrated on

Easter Monday

instead. The

Russian Orthodox Church

also celebrates two

additional feasts in honour of St. George: one on November 3 commemorating the

consecration

of a

cathedral

dedicated to him in

Lydda during the reign

Constantine the Great

(305–37). When the church

was consecrated, the relics

of the St. George were transferred

there. The other feast on November 26 for a church dedicated to him in

Kiev, ca. 1054.

In Egypt

the

Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria

refers to

St George as the “Prince of Martyrs” and celebrates his martyrdom on the 23rd of

Paremhat

of the

Coptic Calendar

equivalent to May 1. The

Copts

also celebrate the

consecration

of the first church dedicated to

him on 7th of the month of Hatour of the Coptic Calender usually equivalent to

17 November.

Patronages

A highly celebrated saint in both the

Western

and

Eastern

Christian

churches, a large number of

Patronages of Saint George

exist throughout the

world.[41]

St. George is the patron saint of England. His cross forms the national

flag of England

, and features within the

Union Flag

of the

United Kingdom

, and other national flags

containing the Union Flag, such as those of

Australia

and

New Zealand

. Traces of the cult of Saint George

in England pre-date the

Norman Conquest

in the eleventh century;[citation

needed] by the fourteenth century the saint had been

declared both the patron saint and the protector of the royal family.[42]

St George’s monument in

Tbilisi

,

Georgia

.

The

country of Georgia

, where devotions to the

saint date back to the fourth century, is not technically named after the saint,

but is a well-attested

backward derivation

of the English name.

However, a large number of towns and cities around the world are. Saint George

is one of the patron Saints of Georgia; the name Georgia (Sakartvelo in

Georgian) is an anglicisation

of Gurj, derived from the

Persian

word for the frightening and heroic

people in that territory.[43]

However, chronicles describing the land as Georgie or Georgia in French

and English, date from the early Middle Ages “because of their special reverence

for Saint George”,[44]

but these accounts have been seen as

folk etymology

;[citation

needed] compare

Land of Prester John

.

There are exactly 365 Orthodox churches in

Georgia

named after Saint George according to

the number of days in a year. According to myth, St. George was cut into 365

pieces after he fell in battle and every single piece was spread throughout the

entire country.[45][46][47]

According to another myth, Saint George appeared in person during the

Battle of Didgori

to support the Georgian

victory over the

Seldjuk army

and the Georgian uprising against

Persian rule. Saint George is considered by many Georgians to have special

meaning as a symbol of national liberation.[48]

Devotions to Saint George in

Portugal

date back to the twelfth century, and

Saint Constable

attributed the victory of the

Portuguese in the

battle of Aljubarrota

in the fourteenth century

to Saint George. During the reign of King

John I

(1357–1433) Saint George became the

patron saint of Portugal and the King ordered that the saint’s image on the

horse be carried in the

Corpus Christi

procession. In fact, the

Portuguese Army motto means Portugal and Saint George, in perils and in efforts

of war.[49]

Saint George is also one of the patron saints of the Mediterranean islands of

Malta

and

Gozo. In a battle between the Maltese and the Moors, Saint George was

alleged to have been seen with Saint Paul and Saint Agata, protecting the

Maltese. Besides being the patron of Victoria where

St. George’s Basilica, Malta

is dedicated to

him, St George is the protector of the island Gozo.[50]

Interfaith Shrine

There is a tradition in the Holy Land of Christians and Muslim going to an

Eastern Orthodox

shrine of St. George at

Beith Jala

, Jews also attend the site in the

belief that the prophet

Elijah

was buried there. This is testified to

by

Elizabeth Finn

in 1866, where she wrote, “St.

George killed the dragon in this country

Palestine

; and the place is shown close to

Beirut

(Lebanon).

Many churches and convents are named after him. The church at

Lydda is dedicated to St. George: so is a convent near Bethlehem, and

another small one just opposite the Jaffa gate; and others beside. The Arabs

believe that St. George can restore mad people to their senses; and to say a

person has been sent to St. George’s, is equivalent to saying he has been sent

to a madhouse. It is singular that the Moslem Arabs share this veneration for

St. George, and send their mad people to be cured by him, as well as the

Christians. But they commonly call him

El Khudder

—The Green—according to their

favourite manner of using epithets instead of names. Why he should be called

green, however, I cannot tell—unless it is from the colour of his horse. Gray

horses are called green in Arabic.”[51]

A possible explanation for this colour reference is

Al Khidr

, the erstwhile tutor of Moses, gained

his name from having sat in a barren desert, turning it into a lush green

paradise.[52][53]

William Dalrymple

reviewing the literature in

1999 tells us that

J. E. Hanauer

in his 1907 book Folklore of

the Holy Land: Muslim, Christian and Jewish “mentioned a shrine in the

village of Beit Jala, beside Bethlehem, which at the time was frequented by all

three of Palestine’s religious communities. Christians regarded it as the

birthplace of St. George, Jews as the burial place of the Prophet Elias.

According to Hanauer, in his day the monastery was “a sort of madhouse. Deranged

persons of all the three faiths are taken thither and chained in the court of

the chapel, where they are kept for forty days on bread and water, the

Eastern Orthodox

priest at the head of the

establishment now and then reading the Gospel over them, or administering a

whipping as the case demands.’[54]

In the 1920s, according to

Taufiq Canaan

‘s Mohammedan Saints and

Sanctuaries in Palestine, nothing seemed to have changed, and all three

communities were still visiting the shrine and praying together.”[55]

Dalrymple himself visited the place in 1995. “I asked around in the Christian

Quarter in Jerusalem, and discovered that the place was very much alive. With

all the greatest shrines in the Christian world to choose from, it seemed that

when the local Arab Christians had a problem – an illness, or something more

complicated: a husband detained in an Israeli prison camp, for example – they

preferred to seek the intercession of St George in his grubby little shrine at

Beit Jala rather than praying at the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or the Church

of the Nativity in Bethlehem.”[55]

He asked the priest at the shrine “Do you get many Muslims coming here?” The

priest replied, “We get hundreds! Almost as many as the Christian pilgrims.

Often, when I come in here, I find Muslims all over the floor, in the aisles, up

and down.”[55][56][57]

The Encyclopædia Britannica quotes G.A. Smith in his Historic

Geography of the Holy Land p. 164 saying “The Mahommedans who usually

identify St. George with the prophet Elijah, at Lydda confound his legend with

one about Christ himself. Their name for Antichrist is Dajjal, and they have a

tradition that Jesus will slay Antichrist by the gate of Lydda. The notion

sprang from an ancient

bas-relief

of George and the Dragon on the

Lydda church. But Dajjal may be derived, by a very common confusion between n

and l, from Dagon, whose name two neighbouring villages bear to this day, while

one of the gates of Lydda used to be called the Gate of Dagon.”[58]

Colours and flag

St George’s cross

The “Colours of Saint George”, or

St George’s Cross

are a white flag with a red

cross, frequently borne by entities over which he is patron (e.g. the

Republic of Genoa

and then

Liguria

,

England

,

Georgia

,

Catalonia

,

Aragon

, etc.).

This was formerly the banner attributed to

St. Ambrose

. Adopted by the city of

Milan

(of which he was Archbishop) at least as

early as the 9th century, its use spread over Northern Italy including Genoa.[dubious

–

discuss

] Genoa’s patron saint

was St. George and while the flag was not associated with George in Genoa

itself, it is possibly[clarification

needed] the cause of the use of the design as the

attributed arms

of Saint George in the 14th

century.[dubious

–

discuss

]

The same colour scheme was used by

Viktor Vasnetsov

for the façade of the

Tretyakov Gallery

, in which some of the most

famous St. George icons are exhibited and which displays St. George as the coat

of arms of Moscow over its entrance.

In 1606, the

flag of England

(St.

George’s Cross), and the

flag of Scotland

(St.

Andrew’s Cross), were joined together to create the

Union Flag

.[59]

Iconography and models

Byzantine

icon of St. George,

Athens

Greece

St. George is most commonly depicted in early

icons

,

mosaics

and

frescos

wearing armour contemporary with the

depiction, executed in gilding and silver colour, intended to identify him as a

Roman soldier

. After the

Fall of Constantinople

and the association of

St George with the

crusades

, he is more often portrayed mounted

upon a

white horse

.

At the same time St George began to be associated with

St. Demetrius

, another early

soldier saint

. When the two saints are

portrayed together mounted upon horses, they may be likened to earthly

manifestations of the archangels

Michael

and

Gabriel

. St George is always depicted in

Eastern traditions upon a white horse and St. Demetrius on a red horse[60]

St George can also be identified in the act of spearing a dragon, unlike St

Demetrius, who is sometimes shown spearing a human figure, understood to

represent Maximian

.

A 2003 Vatican stamp issued on the anniversary of the Saint’s death depicts

an armoured Saint George atop a white horse, killing the dragon.[61]

During the early second millennium, George came to be seen as the model of

chivalry

, and during this time was depicted in

works of literature

, such as the

medieval romances

.

Jacobus de Voragine

,

Archbishop

of

Genoa

, compiled the Legenda Sanctorum, (Readings

of the Saints) also known as Legenda Aurea (the

Golden Legend

) for its worth among readers.

Its 177 chapters (182 in other editions) contain the story of Saint George.

Modern Russians interpret the icon not as a killing but as a struggle,

against ourselves and the evil among us. In Eastern Orthodox Christianity it is

possible to find Icons of St.George riding on Black horse, as well, there are

various examples in Russian Iconography, like the Icon in British Museum

Collection.

In the eastern Christian tradition, Saint George is portrayed as a martyr in

the classical orthodox icon style; he is either portrayed as a soldier with his

weapons, or in the more famous setting of him riding a white horse and slaying

the dragon. One exception to this icon tradition exists in the Saint George

Church for Melkite Catholics, in the Lebanese village of

Mieh Mieh

in south Lebanon, where you can find

hanging on its walls the only icons in the world (drawn according to the eastern

icon style) portraying the whole life of Saint George as well as the scenes of

his torture and martyrdom. This unique set was completed for the church’s 75th

jubilee in 2012, under the guidance of Mgr Sassine Gregoire.

The Byzantine Empire was

the predominantly Greek-speaking

continuation of the Roman

Empire during Late

Antiquity and the Middle

Ages. Its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul),

originally known as Byzantium.

Initially the eastern half of the Roman Empire (often called the Eastern

Roman Empire in this context), it

survived the 5th century fragmentation

and collapse of the Western

Roman Empire and continued

to thrive, existing for an additional thousand years until it fell to

the Ottoman

Turks in 1453. During most

of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and

military force in Europe. Both “Byzantine Empire” and “Eastern Roman Empire” are

historiographical terms applied in later centuries; its citizens continued to

refer to their empire as the Roman

Empire (Ancient

Greek: Βασιλεία

Ῥωμαίων, tr.Basileia

Rhōmaiōn; Latin: Imperium

Romanum), and Romania.

Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the transitional period during

which the Roman Empire’s east

and west divided.

In 285, theemperor Diocletian (r.

284–305) partitioned the Roman Empire’s administration into eastern and western

halves. Between

324 and 330,Constantine

I (r. 306–337) transferred

the main capital from Rome to Byzantium,

later known as Constantinople (“City

of Constantine”) and Nova Roma (“New

Rome”). Under Theodosius

I (r. 379–395), Christianity became

the Empire’s official state

religion and others such

as Roman

polytheism were proscribed.

And finally, under the reign of Heraclius (r.

610–641), the Empire’s military and administration were restructured and adopted

Greek for official use instead of Latin. In

summation, Byzantium is distinguished from ancient

Rome proper insofar as it

was oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by Orthodox

Christianity rather than Roman

polytheism.

The borders of the Empire evolved a great deal over its existence, as it went

through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of

Justinian I

(r.

527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the

historically Roman western Mediterranean coast,

including north Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more

centuries. During the reign of Maurice (r.

582–602), the Empire’s eastern frontier was expanded and north stabilised.

However, his assassination caused a two-decade-long

war with Sassanid

Persia which exhausted the

Empire’s resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the Muslim

conquests of the 7th

century. During the 10th-centuryMacedonian

dynasty, the Empire experienced a golden

age, which culminated in the reign of Emperor

Basil II “the Bulgar-Slayer”. However, shortly after Basil’s death, a

neglect of the vast military built up during the Late Macedonian

dynasty caused the Empire

to begin to lose territory in Asia Minor to the Seljuk

Turks. Emperor

Romanos IV Diogenes and

several of his predecessors had attempted to rid Eastern

Anatolia of the Turkish

menace, but this endeavor proved ultimately untenable – especially after the

disastrous Battle

of Manzikert in 1071.

Despite a prominent period

of revival (1081-1180) under

the steady leadership of the Komnenos

family, who played an instrumental role in theFirst and Second

Crusades, the final centuries of the Empire exhibit a general trend

of decline. In 1204, after a period

of strife following the

downfall of the Komnenos

dynasty, the Empire was delivered a mortal blow by the forces of the Fourth

Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked and the Empire dissolved

and divided into competing

Byzantine Greek and Latin

realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople and re-establishment

of the Empire in 1261, Byzantium remained only one of a number of

small rival states in the area for the final two centuries of its existence.

This volatile period lead to its progressive

annexation by the Ottomans over

the 15th century and the Fall

of Constantinople in 1453.

Early history

The Baptism of Constantine painted

byRaphael‘s

pupils (1520–1524, fresco,

Vatican City,Apostolic

Palace). Eusebius

of Caesarea records

that (as was

common among converts of early Christianity) Constantine

delayed receiving baptismuntil

shortly before his death.

The Roman

army succeeded in

conquering many territories covering the entire Mediterranean region and coastal

regions in southwestern

Europe and north Africa.

These territories were home to many different cultural groups, ranging from

primitive to highly sophisticated. Generally speaking, the eastern Mediterranean

provinces were more urbanised than the western, having previously been united

under the Macedonian

Empire and Hellenisedby

the influence of Greek culture.

The west also suffered more heavily from the instability of the 3rd century AD.

This distinction between the established Hellenised East and the younger

Latinised West persisted and became increasingly important in later centuries,

leading to a gradual estrangement of the two worlds.

Divisions of the

Roman Empire

In order to maintain control and improve administration, various schemes to

divide the work of the Roman Emperor by sharing it between individuals were

tried between 285 and 324, from 337 to 350, from 364 to 392, and again between

395 and 480. Although the administrative subdivisions varied, they generally

involved a division of labour between East and West. Each division was a form of

power-sharing (or even job-sharing), for the ultimateimperium was

not divisible and therefore the empire remained legally one state—although the

co-emperors often saw each other as rivals or enemies rather than partners.

In 293, emperor Diocletian created

a new administrative system (the tetrarchy),

in order to guarantee security in all endangered regions of his Empire. He

associated himself with a co-emperor (Augustus),

and each co-emperor then adopted a young colleague given the title of Caesar,

to share in their rule and eventually to succeed the senior partner. The

tetrarchy collapsed, however, in 313 and a few years later Constantine I

reunited the two administrative divisions of the Empire as sole Augustus.

Loss of the

western Roman Empire

After the fall of Attila, the Eastern Empire enjoyed a period of peace, while

the Western Empire deteriorated in continuing migration and expansion byGermanic

nations (its end is

usually dated in 476 when the Germanic Roman general Odoacer deposed

the titular Western Emperor Romulus

Augustulus). In 480 Emperor Zeno abolished

the division of the Empire making himself sole Emperor. Odoacer, now ruler of

Italy, was nominally Zeno’s subordinate but acted with complete autonomy,

eventually providing support of a rebellion against the Emperor.

Zeno negotiated with the conquering Ostrogoths,

who had settled in Moesia,

convincing the Gothic king Theodoric to

depart for Italy as magister

militum per Italiam (“commander

in chief for Italy”) with the aim to depose Odoacer. By urging Theodoric into

conquering Italy, Zeno rid the Eastern Empire of an unruly subordinate (Odoacer)

and moved another (Theodoric) further from the heart of the Empire. After

Odoacer’s defeat in 493, Theodoric ruled Italy on his own, although he was never

recognised by the eastern emperors as “king” (rex).

In 491, Anastasius

I, an aged civil officer of Roman origin, became Emperor, but it was

not until 497 that the forces of the new emperor effectively took the measure of Isaurian

resistance.[29]Anastasius

revealed himself as an energetic reformer and an able administrator. He

perfected Constantine I’s coinage system by definitively setting the weight of

the copper follis,

the coin used in most everyday transactions.[30] He

also reformed the tax system and permanently abolished the chrysargyron tax.

The State Treasury contained the enormous sum of 320,000 lb (150,000 kg) of gold

when Anastasius died in 518.

Reconquest of

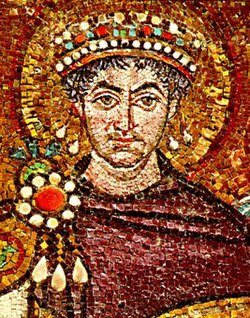

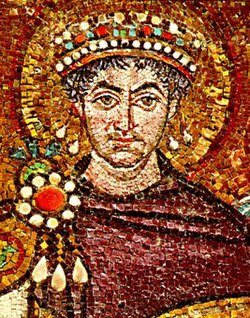

the western provinces

Justinian I

depicted

on one of the famous mosaics of the Basilica

of San Vitale, Ravenna.

Justinian I

, the son of an Illyrian peasant,

may already have exerted effective control during the reign of his uncle, Justin

I (518–527). He

assumed the throne in 527, and oversaw a period of recovery of former

territories. In 532, attempting to secure his eastern frontier, he signed a

peace treaty with Khosrau

I of Persia agreeing to

pay a large annual tribute to the Sassanids.

In the same year, he survived a revolt in Constantinople (the Nika

riots), which solidified his power but ended with the deaths of a

reported 30,000 to 35,000 rioters on his orders.

In 529, a ten-man commission chaired by John

the Cappadocian revised

the Roman law and created a new codification of

laws and jurists’ extracts. In 534, the Code was

updated and, along with the enactements

promulgated by Justinian after 534, it formed the system of law used

for most of the rest of the Byzantine era.

The western conquests began in 533, as Justinian sent his general Belisarius to

reclaim the former province of Africa from

the Vandals who

had been in control since 429 with their capital at Carthage. Their

success came with surprising ease, but it was not until 548 that the major local

tribes were subdued. In Ostrogothic

Italy, the deaths of Theodoric, his nephew and heir Athalaric,

and his daughter Amalasuntha had

left her murderer,Theodahad (r.

534–536), on the throne despite his weakened authority.

Heraclian dynasty

The Byzantine Empire in 650 – by this year it lost all of its

southern provinces except the Exarchate

of Africa.

After Maurice’s murder by Phocas,

Khosrau used the pretext to reconquer the Roman

province of Mesopotamia.Phocas, an unpopular ruler invariably

described in Byzantine sources as a “tyrant”, was the target of a number of

Senate-led plots. He was eventually deposed in 610 by Heraclius, who sailed to

Constantinople from Carthage with

an icon affixed to the prow of his ship.

Following the ascension of Heraclius, the Sassanid advance pushed deep into Asia

Minor, occupying Damascus andJerusalem and

removing the True

Cross to Ctesiphon. The

counter-attack launched by Heraclius took on the character of a holy war, and an acheiropoietos image

of Christ was carried as a military standard (similarly,

when Constantinople was saved from an Avar siege in 626, the victory was

attributed to the icons of the Virgin that were led in procession byPatriarch

Sergius about the walls of

the city).

The main Sassanid force was destroyed at Nineveh in

627, and in 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic

ceremony. The war had exhausted both

the Byzantines and Sassanids, however, and left them extremely vulnerable to the Muslim

forces that emerged in the

following years. The Byzantines

suffered a crushing defeat by the Arabs at the Battle

of Yarmouk in 636, while

Ctesiphon fell in 634.

Siege of Constantinople (674–678)

The Arabs, now firmly in control

of Syria and the Levant, sent frequent raiding parties deep into Asia

Minor, and in 674–678

laid siege to Constantinople itself.

The Arab fleet was finally repulsed through the use of Greek

fire, and a thirty-years’ truce was signed between the Empire and the Umayyad

Caliphate. However, the Anatolian raids

continued unabated, and accelerated the demise of classical urban culture, with

the inhabitants of many cities either refortifying much smaller areas within the

old city walls, or relocating entirely to nearby fortresses. Constantinople

itself dropped substantially in size, from 500,000 inhabitants to just

40,000–70,000, and, like other urban centres, it was partly ruralised. The city

also lost the free grain shipments in 618, after Egypt fell first to the

Persians and then to the Arabs, and public wheat distribution ceased.

The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions

was filled by the theme system, which entailed dividing Asia Minor into

“provinces” occupied by distinct armies that assumed civil authority and

answered directly to the imperial administration. This system may have had its

roots in certain ad hoc measures

taken by Heraclius, but over the course of the 7th century it developed into an

entirely new system of imperial governance.[59] The

massive cultural and institutional restructuring of the Empire consequent on the

loss of territory in the 7th century has been said to have caused a decisive

break in east Mediterranean Romanness and

that the Byzantine state is subsequently best understood as another successor

state rather than a real continuation of the Roman Empire.

The Greek fire was first used by the Byzantine

Navy during

the Byzantine-Arab Wars (from theMadrid

Skylitzes, Biblioteca

Nacional de España, Madrid).

Isaurian dynasty to the ascension of Basil I

The Byzantine Empire at the accession of Leo III, c. 717. Striped

area indicates land raided by the Arabs.

Leo III the Isaurian

turned

back the Muslim assault in 718 and addressed himself to the task of reorganising

and consolidating the themes in Asia Minor. His successor, Constantine

V, won noteworthy victories in northern Syria and thoroughly

undermined Bulgarian strength.

Taking advantage of the Empire’s weakness after the Revolt

of Thomas the Slav in the

early 820s, the Arabs reemerged andcaptured

Crete. They also successfully attacked Sicily, but in 863 general Petronas gained

a huge

victory against Umar

al-Aqta, the emir of Melitene.

Under the leadership of emperor Krum,

the Bulgarian threat also reemerged, but in 815–816 Krum’s son, Omurtag,

signed a peace

treaty with Leo

V.

Macedonian dynasty and resurgence (867–1025)

The Byzantine Empire, c. 867.

The accession of Basil

I to the throne in 867

marks the beginning of the Macedonian

dynasty, which would rule for the next two and a half centuries. This

dynasty included some of the most able emperors in Byzantium’s history, and the

period is one of revival and resurgence. The Empire moved from defending against

external enemies to reconquest of territories formerly lost.[70]

In addition to a reassertion of Byzantine military power and political

authority, the period under the Macedonian dynasty is characterised by a

cultural revival in spheres such as philosophy and the arts. There was a

conscious effort to restore the brilliance of the period before the Slavic and

subsequent Arab

invasions, and the Macedonian era has been dubbed the “Golden Age” of

Byzantium. Though the Empire was

significantly smaller than during the reign of Justinian, it had regained

significant strength, as the remaining territories were less geographically

dispersed and more politically, economically, and culturally integrated.

Wars against the Arabs

The general Leo

Phokas defeats

the Arabs atAndrassos in

960, from the Madrid

Skylitzes.

In the early years of Basil I’s reign, Arab raids on the coasts of Dalmatia were

successfully repelled, and the region once again came under secure Byzantine

control. This enabled Byzantine missionaries to penetrate to the interior and

convert the Serbs and the principalities of modern-dayHerzegovina and Montenegro to

Orthodox Christianity. An attempt to

retake Malta ended

disastrously, however, when the local population sided with the Arabs and

massacred the Byzantine garrison.

By contrast, the Byzantine position in Southern

Italy was gradually

consolidated so that by 873 Bari had

once again come under Byzantine rule,and most of Southern Italy would remain in

the Empire for the next 200 years.On the more important eastern front, the

Empire rebuilt its defences and went on the offensive. The Paulicians were

defeated and their capital of Tephrike (Divrigi) taken, while the offensive

against the Abbasid

Caliphatebegan with the recapture of Samosata.

The military successes of the 10th century were coupled with a major

cultural revival, the so-called Macedonian

Renaissance. Miniature from the Paris

Psalter, an example of Hellenistic-influenced art.

Under Michael’s son and successor, Leo

VI the Wise, the gains in the east against the now weak Abbasid

Caliphate continued. However, Sicily was lost to the Arabs in 902, and in 904 Thessaloniki,

the Empire’s second city, was sacked by an Arab fleet. The weakness of the

Empire in the naval sphere was quickly rectified, so that a few years later a

Byzantine fleet had re-occupied Cyprus,

lost in the 7th century, and also stormed Laodicea in

Syria. Despite this revenge, the Byzantines were still unable to strike a

decisive blow against the Muslims, who inflicted a crushing defeat on the

imperial forces when they attempted to regain Crete in

911.

Wars against

the Bulgarian Empire

Emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025).

The traditional struggle with the See

of Rome continued through

the Macedonian period, spurred by the question of religious supremacy over the

newly Christianised state of Bulgaria. Ending

eighty years of peace between the two states, the powerful Bulgarian tsar Simeon

I invaded in 894 but was pushed back by the Byzantines, who used their fleet to

sail up the Black

Sea to attack the

Bulgarian rear, enlisting the support of theHungarians. The

Byzantines were defeated at the Battle

of Boulgarophygon in 896,

however, and agreed to pay annual subsidies to the Bulgarians.

Leo the Wise died in 912, and hostilities soon resumed as Simeon marched to

Constantinople at the head of a large army. Though

the walls of the city were impregnable, the Byzantine administration was in

disarray and Simeon was invited into the city, where he was granted the crown ofbasileus (emperor)

of Bulgaria and had the young emperor Constantine

VII marry one of his

daughters. When a revolt in Constantinople halted his dynastic project, he again

invaded Thrace and conquered Adrianople. The

Empire now faced the problem of a powerful Christian state within a few days’

marching distance from Constantinople, as

well as having to fight on two fronts.

A great imperial expedition under Leo

Phocas and Romanos

I Lekapenos ended with

another crushing Byzantine defeat at the Battle

of Achelous in 917, and

the following year the Bulgarians were free to ravage northern Greece.

Adrianople was plundered again in 923, and a Bulgarian army laid siege to

Constantinople in 924. Simeon died suddenly in 927, however, and Bulgarian power

collapsed with him. Bulgaria and Byzantium entered a long period of peaceful

relations, and the Empire was now free to concentrate on the eastern front

against the Muslims. In 968, Bulgaria

was overrun by the Rus’ under Sviatoslav

I of Kiev, but three years later, John I Tzimiskes defeated the

Rus’ and re-incorporated Eastern Bulgaria into the Byzantine Empire.

The extent of the Empire under Basil

II.

Bulgarian resistance revived under the rule of the Cometopuli

dynasty, but the new emperor Basil II (r. 976–1025) made the

submission of the Bulgarians his primary goal. Basil’s

first expedition against Bulgaria, however, resulted in a humiliating defeat at

the Gates

of Trajan. For the next few years, the emperor would be preoccupied

with internal revolts in Anatolia, while the Bulgarians expanded their realm in

the Balkans. The war dragged on for nearly twenty years. The Byzantine victories

of Spercheios and Skopje decisively

weakened the Bulgarian army, and in annual campaigns, Basil methodically reduced

the Bulgarian strongholds.[84] At

the Battle

of Kleidion in 1014 the

Bulgarians were annihilated: their army was captured, and it is said that 99 out

of every 100 men were blinded, with the hundredth man left with one eye so he

could lead his compatriots home. When Tsar Samuil saw

the broken remains of his once gallant army, he died of shock. By 1018, the last

Bulgarian strongholds had surrendered, and the country became part of the

Empire.[84] This

victory restored the Danube frontier, which had not been held since the days of

the emperor Heraclius.

Relations with

the Kievan Rus’

Rus’

under

the walls of Constantinople (860).

Between 850 and 1100, the Empire developed a mixed relationship with the new

state of the Kievan

Rus’, which had emerged to the north across the Black Sea.[85] This

relationship would have long-lasting repercussions in the history of the East

Slavs, and the Empire quickly became the main tradingand

cultural partner for Kiev. The Rus’ launched their first attack against

Constantinople in

860, pillaging the suburbs of the city. In 941, they

appeared on the Asian shore of

the Bosphorus, but this time they were crushed, an indication of the

improvements in the Byzantine military position after 907, whenonly

diplomacy had been able to push back the invaders. Basil II could not

ignore the emerging power of the Rus’, and, following the example of his

predecessors, he used religion as a means for the achievement of political

purposes. Rus’–Byzantine relations

became closer following the marriage of the Anna

Porphyrogeneta to Vladimir

the Great in 988, and the

subsequent Christianisation

of the Rus’. Byzantine

priests, architects, and artists were invited to work on numerous cathedrals and

churches around Rus’, expanding Byzantine cultural influence even further, while

numerous Rus’ served in the Byzantine army as mercenaries, most notably as the

famous Varangian

Guard.

Even after the Christianisation of the Rus’, however, relations were not always

friendly. The most serious conflict between the two powers was the war of

968–971 in Bulgaria, but several Rus’ raiding expeditions against the Byzantine

cities of the Black Sea coast and Constantinople itself are also recorded.

Although most were repulsed, they were often followed by treaties that were

generally favourable to the Rus’, such as the one concluded at the end of the

war of 1043, during which the Rus’ gave an indication of their

ambitions to compete with the Byzantines as an independent power.

Apex

Constantinople became the largest and wealthiest city in Europe

between the 9th and 11th centuries.

By 1025, the date of Basil II’s death, the Byzantine Empire stretched from Armenia in

the east to Calabria in

Southern Italy in the west. Many

successes had been achieved, ranging from the conquest of Bulgaria to the

annexation of parts of Georgia and

Armenia, and the reconquest of Crete, Cyprus, and the important city of Antioch.

These were not temporary tactical gains but long-term reconquests.

Leo VI achieved the complete codification of Byzantine law in Greek. This

monumental work of 60 volumes became the foundation of all subsequent Byzantine

law and is still studied today. Leo

also reformed the administration of the Empire, redrawing the borders of the

administrative subdivisions (the Themata,

or “Themes”) and tidying up the system of ranks and privileges, as well as

regulating the behavior of the various trade guilds in Constantinople. Leo’s

reform did much to reduce the previous fragmentation of the Empire, which

henceforth had one center of power, Constantinople. However,

the increasing military success of the Empire greatly enriched and empowered the

provincial nobility with respect to the peasantry, who were essentially reduced

to a state of serfdom.

Under the Macedonian emperors, the city of Constantinople flourished, becoming

the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, with a population of approximately

400,000 in the 9th and 10th centuries. During

this period, the Byzantine Empire employed a strong civil service staffed by

competent aristocrats that oversaw the collection of taxes, domestic

administration, and foreign policy. The Macedonian emperors also increased the

Empire’s wealth by fostering trade with Western Europe, particularly through the

sale of silk and metalwork.

Split between Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism (1054)

Mural of Saints

Cyril and Methodius, 19th century, Troyan

Monastery, Bulgaria.

The Macedonian period also included events of momentous religious significance.

The conversion of the Bulgarians, Serbs and Rus’ to

Orthodox Christianity permanently changed the religious map of Europe and still

resonates today. Cyril

and Methodius, two Byzantine

Greek brothers from

Thessaloniki, contributed significantly to the Christianization

of the Slavs and in the

process devised the Glagolitic

alphabet, ancestor to the Cyrillic

script.

In 1054, relations between the Eastern and Western traditions within the

Christian Church reached a terminal crisis, known as the Great

Schism. Although there was a formal declaration of institutional

separation, on July 16, when three papal legates entered the Hagia Sophia during

Divine Liturgy on a Saturday afternoon and placed a bull of excommunication on

the altar, the so-called Great Schism

was actually the culmination of centuries of gradual separation.

Crisis and fragmentation

The Empire soon fell into a period of difficulties, caused to a large extent by

the undermining of the theme system and the neglect of the military. Nikephoros

II Phokas (reigned

963–969), John Tzimiskes and Basil II changed the military divisions (τάγματα, tagmata)

from a rapid response, primarily defensive, citizen army into a professional,

campaigning army increasingly manned by mercenaries. Mercenaries,

however, were expensive and as the threat of invasion receded in the 10th

century, so did the need for maintaining large garrisons and expensive

fortifications.[95]

Basil II left a burgeoning treasury upon his death, but neglected to plan for

his succession. None of his immediate successors had any particular military or

political skill and the administration of the Empire increasingly fell into the

hands of the civil service. Efforts to revive the Byzantine economy only

resulted in inflation and a debased gold coinage. The army was now seen as both

an unnecessary expense and a political threat. Therefore, native troops were

cashiered and replaced by foreign mercenaries on specific contract.

Komnenian

dynasty and the crusaders

Alexios I

, founder of the Komnenos

dynasty.

The period from about 1081 to about 1185 is often known as the Komnenian or

Comnenian period, after the Komnenos

dynasty. Together, the five Komnenian emperors (Alexios I, John II,

Manuel I, Alexios II and Andronikos I) ruled for 104 years, presiding over a

sustained, though ultimately incomplete, restoration of the military,

territorial, economic and political position of the Byzantine Empire. Though

the Seljuk Turks occupied the Empire’s heartland in Anatolia, it was against

Western powers that most Byzantine military efforts were directed, particularly

the Normans.

The Empire under the Komnenoi played a key role in the history of the Crusades

in the Holy Land, which Alexios I had helped bring about, while also exerting

enormous cultural and political influence in Europe, the Near East, and the

lands around the Mediterranean Sea under John and Manuel. Contact between

Byzantium and the “Latin” West, including the Crusader states, increased

significantly during the Komnenian period. Venetian and other Italian traders

became resident in Constantinople and the empire in large numbers (there were an

estimated 60,000 Latins in Constantinople alone, out of a population of three to

four hundred thousand), and their presence together with the numerous Latin

mercenaries who were employed by Manuel helped to spread Byzantine technology,

art, literature and culture throughout the Latin West, while also leading to a

flow of Western ideas and customs into the Empire.

In terms of prosperity and cultural life, the Komnenian period was one of the

peaks in Byzantine history, and

Constantinople remained the leading city of the Christian world in terms of

size, wealth, and culture. There was

a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy, as well as an increase in

literary output in vernacular Greek. Byzantine

art and literature held a pre-eminent place in Europe, and the cultural impact

of Byzantine art on the west during this period was enormous and of long lasting

significance.

Alexios I and the

First Crusade

After Manzikert, a partial recovery (referred to as the Komnenian restoration)

was made possible by the efforts of the Komnenian dynasty. The

first emperor of this dynasty was Isaac

I (1057–1059) and the

second Alexios I. At the very outset of his reign, Alexios faced a formidable

attack by the Normans under Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund

of Taranto, who captured Dyrrhachium and Corfu,

and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly.

Robert Guiscard’s death in 1085 temporarily eased the Norman problem. The

following year, the Seljuq sultan died, and the sultanate was split by internal

rivalries. By his own efforts, Alexios defeated the Pechenegs;

they were caught by surprise and annihilated at the Battle

of Levounion on 28 April

1091.

The Byzantine Empire and the Sultanate

of Rûm before

the First

Crusade.

Having achieved stability in the West, Alexios could turn his attention to the