|

Greek city of Menainon in Sicily

Bronze Tetras 20mm (4.14 grams) Struck circa 175-125 B.C.

Reference: Calciati III pg. 183, 1; SNG ANS 292 variety; RARE

Laureate and draped bust of Zeus Serapis right; lotus flower in hair; E behind.

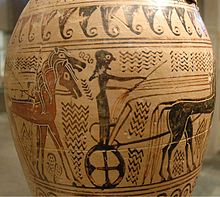

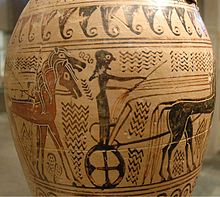

MENAINΩN, Nike driving galloping biga right.

Founded in 459 B.C., Menainon was the subject to Syracuse for much

of its history down to the time of the Roman conquest at the end of the 3rd

Century.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

Serapis is a Graeco-Egyptian god. Serapis was devised during the 3rd

century BC on the orders of

Ptolemy I of Egypt

as a means to unify the

Greeks and Egyptians in his realm. The god was depicted as Greek in appearance,

but with Egyptian trappings, and combined iconography from a great many cults,

signifying both abundance and resurrection. A

serapeum

(Greek serapeion) was any

temple or religious precinct devoted to Serapis. The

cultus

of Serapis was spread as a matter of

deliberate policy by the

Ptolemaic kings

, who also built an immense

Serapeum in Alexandria.

Serapis continued to increase in popularity during the

Roman period

, often replacing

Osiris

as the consort of

Isis in temples outside Egypt. In 389, a mob led by the

Patriarch

Theophilus of Alexandria

destroyed the

Alexandrian Serapeum, but the cult survived until all forms of religion other

than

Nicene Christianity

were suppressed or

abolished under

Theodosius I

in 391.

About the god

This pendant bearing Serapis’s likeness would have been worn by a

member of elite Egyptian society.

Walters Art Museum

,

Baltimore

.

“Serapis” is the only form used in Latin, but both

Ancient Greek

:

Σάραπις Sárapis and

Ancient Greek

:

Σέραπις Sérapis appear in Greek, as well as

Ancient Greek

:

Σαραπo Serapo in Bactrian.

His most renowned temple was the

Serapeum of Alexandria

. Under

Ptolemy Soter

, efforts were made to integrate

Egyptian religion with that of their Hellenic rulers. Ptolemy’s policy was to

find a deity that should win the reverence alike of both groups, despite the

curses of the Egyptian priests against the gods of the previous foreign rulers

(e.g.

Set

, who was lauded by the

Hyksos

).

Alexander the Great

had attempted to use

Amun for this purpose, but he was more prominent in

Upper Egypt

, and not as popular with those in

Lower Egypt

, where the Greeks had stronger

influence. The Greeks had little respect for animal-headed figures, and so a

Greek-style

anthropomorphic

statue was chosen as the

idol

, and proclaimed as the equivalent of the

highly popular

Apis

. It was named Aser-hapi (i.e.

Osiris-Apis), which became Serapis, and was said to be

Osiris

in full, rather than just his

Ka

(life force).

History

The earliest mention of a Serapis is in the disputed death scene of Alexander

(323 BC). Here, Serapis has a temple at

Babylon

, and is of such importance that he

alone is named as being consulted on behalf of the dying king. His presence in

Babylon would radically alter perceptions of the mythologies of this era: the

unconnected Babylonian god Ea (Enki)

was titled Serapsi, meaning ‘king of the deep’, and it is possible this

Serapis is the one referred to in the diaries. The significance of this Serapsi

in the Hellenic psyche, due to its involvement in Alexander’s death, may have

also contributed to the choice of Osiris-Apis as the chief Ptolemaic god.

According to Plutarch

, Ptolemy stole the

cult statue

from

Sinope

, having been instructed in a dream by

the “unknown

god” to bring the statue to

Alexandria

, where the statue was pronounced to

be Serapis by two religious experts. One of the experts was of the

Eumolpidae

, the ancient family from whose

members the hierophant

of the

Eleusinian Mysteries

had been chosen since

before history, and the other was the scholarly Egyptian priest

Manetho

, which gave weight to the judgement

both for the Egyptians

and the Greeks.

Plutarch may not be correct, however, as some Egyptologists allege that the

Sinope in the tale is really the hill of Sinopeion, a name given to the site of

the already existing

Serapeum

at

Memphis

. Also, according to

Tacitus

, Serapis (i.e., Apis explicitly

identified as Osiris in full) had been the god of the village of

Rhakotis

before it expanded into the great

capital of Alexandria.

High Clerk in the Cult of Serapis,

Altes Museum

,

Berlin

The statue suitably depicted a figure resembling

Hades

or

Pluto

, both being kings of the Greek

underworld

, and was shown enthroned with the

modius

, a basket/grain-measure, on his head,

since it was a Greek

symbol

for the land of the dead. He also held a

sceptre

in his hand indicating his rulership,

with Cerberus

, gatekeeper of the underworld, resting

at his feet, and it also had what appeared to be a

serpent

at its base, fitting the Egyptian

symbol of rulership, the

uraeus

.

With his (i.e. Osiris’s) wife

Isis, and their son

Horus

(in the form of

Harpocrates

), Serapis won an important place in

the

Greek world

. In his Description of Greece,

Pausanias notes two Serapeia on the slopes of

Acrocorinth

, above the rebuilt Roman city of

Corinth

and one at Copae in Boeotia.

Serapis was among the

international deities

whose cult was received

and disseminated throughout the Roman Empire, with

Anubis

sometimes identified with Cerberus. At

Rome, Serapis was worshiped in the Iseum Campense, the sanctuary of Isis built

during the

Second Triumvirate

in the

Campus Martius

. The Roman cults of Isis and

Serapis gained in popularity late in the 1st century when

Vespasian

experienced events he attributed to

their miraculous agency while he was in Alexandria, where he stayed before

returning to Rome as emperor in 70. From the

Flavian Dynasty

on, Serapis was one of the

deities who might appear on imperial coinage with the reigning emperor.

The main cult at Alexandria survived until the late 4th century, when a

Christian mob destroyed the Serapeum of Alexandria

in 385, and the cult was part of the general proscription of religions other

than approved forms of Christianity under the

Theodosian decree

.

Gallery

-

Oil lamp with a bust of Serapis, flanked by a crescent moon and star

(Roman-era

Ephesus

, 100-150)

-

Statuette possibly of Serapis (but note the

herculean

club) from

Begram

,

Afghanistan

-

Head of Serapis, from a 12-foot statue found off the coast of

Alexandria

-

Head of Serapis (Roman-era Hellenistic terracotta, Staatliches

Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Munich)

In

Greek mythology

,

Nike

was a goddess

who personified

victory

, also known as the Winged Goddess of

Victory. The Roman equivalent was

Victoria

. Depending upon the time of various

myths, she was described as the daughter of

Pallas

(Titan) and

Styx (Water) and the sister of

Kratos

(Strength),

Bia

(Force), and

Zelus

(Zeal). Nike and her siblings were close

companions of Zeus

, the dominant deity of the

Greek pantheon

. According to classical (later)

myth, Styx brought them to Zeus when

the

god was assembling allies for the

Titan War

against the older deities. Nike

assumed the role of the divine

charioteer

, a role in which she often is

portrayed in Classical Greek art. Nike flew around battlefields rewarding the

victors with glory and fame.

Nike is seen with wings in most statues and paintings. Most other winged

deities in the Greek pantheon had shed their wings by Classical times. Nike is

the goddess of strength, speed, and victory. Nike was a very close acquaintance

of Athena

, and is thought to have stood in

Athena’s outstretched hand in the statue of Athena located in the Parthenon.

Nike is one of the most commonly portrayed figures on Greek coins.

Names stemming from Nike include amongst others:

Nicholas

, Nicola, Nick, Nikolai, Nils, Klaas,

Nicole, Ike, Niki, Nikita, Nika, Niketas, and Nico.

The biga (Latin,

plural bigae) is the two-horse

chariot

as used in

ancient Rome

for sport, transportation, and

ceremonies. Other animals may replace horses in art and occasionally for actual

ceremonies. The term biga is also used by modern scholars for the similar

chariots of other

Indo-European

cultures, particularly the

two-horse chariot of the

ancient Greeks

and

Celts

. The driver of a biga is a

bigarius.

Other Latin words that distinguish chariots by the number of animals yoked as

a team are quadriga

, a four-horse chariot used for

racing and associated with the

Roman triumph

; triga, or three-horse

chariot, probably driven for ceremonies more often than racing (see

Trigarium

); and seiugis or seiuga,

the six-horse chariot, more rarely raced and requiring a high degree of skill

from the driver. The biga and quadriga are the most common types.

Two-horse chariots are a common

icon on Roman coins

; see

bigatus

, a type of

denarius

so called because it depicted a

biga. In the

iconography

of

religion

and

cosmology

, the biga represents the moon,

as the quadriga does the sun.

Greek and

Indo-European background

Procession of two-horses chariots on a

loutrophoros

, c. 690 BC

The earliest reference to a chariot race in

Western literature

is an event in the

funeral games

of

Patroclus

in the

Iliad

. In Homeric warfare, elite warriors

were transported to the battlefield in two-horse chariots, but fought on foot;

the chariot was then used for pursuit or flight. Most

Bronze Age

chariots uncovered by archaeology in

Peloponnesian Greece

are bigae.

The date at which chariot races were introduced at the

Olympian Games

is recorded by later sources as

680 BC, when quadrigae competed. Races on horseback were added in 648. At

Athens, two-horse chariot races were a part of athletic competitions from the

560s onward, but were still not a part of the Olympian Games. Bigae drawn

by mules competed in the 70th Olympiad (500 BC), but they were no longer part of

the games after the 84th Olympiad (444 BC). Not until 408 BC did bigae

races begin to be featured at Olympia.

In myth, the biga often functions

structurally

to create a complementary pair or

to link opposites. The chariot of

Achilles

in the

Iliad

(16.152) was drawn by two immortal

horses and a third who was mortal; at 23.295, a mare is yoked with a stallion.

The team of

Adrastos

included the immortal “superhorse”

Areion

and the mortal Kairos. A yoke of two

horses is associated with the Indo-European concept of the Heavenly Twins, one

of whom is mortal, represented among the Greeks by

Castor and Pollux

, the Dioscuri, who were known

for horsemanship.

Bigae at the races

The

consul

advances in his biga

at the

pompa circensis

[12]

(4th century,

opus sectile

from the

Basilica of Junius Bassus

)

Horse- and

chariot-races

were part of the

ludi, sacred games held during

Roman religious festivals

, from

Archaic times

. A

magistrate

who presented games was entitled to

ride in a biga. The sacral meaning of the races, though diminished over

time,[14]

was preserved by iconography in the

Circus Maximus

, Rome’s main racetrack.

Inscriptions referring to the bigarius as young suggest that a racing

driver had to gain experience with a two-horse team before graduating to a

quadriga.

Construction

A main source for the construction of racing bigae is a number of

bronze figurines found throughout the Roman Empire, a particularly detailed

example of which is held by the

British Museum

. Other sources are

reliefs

and

mosaics

. These show a lightweight frame, to

which a minimal shell of fabric or leather was lashed. The

center of gravity

was low, and the wheels were

relatively small, around 65 cm in diameter in proportion to a body 60 cm wide

and 55 cm deep, with a breastwork of about 70 cm in height. The wheels may have

been rimmed with iron, but otherwise metal fittings are kept to a minimum. The

design facilitated speed, maneuverability and stability.

Modern reenactment of a biga race

The weight of the vehicle has been estimated at 25–30 kg, with a maximum

manned weight of 100 kg. The biga is typically built with a single

draught pole for a double yoke, while two poles are used for a quadriga.

The chariot for a two-horse racing team is not thought to differ otherwise from

that drawn by a four-horse team, and so the horses of a biga pulled 50 kg

each, while those of the quadriga pulled 25 kg each.

The models or statuettes of bigae were

art objects

,

toys, or

collector’s items

. They are perhaps comparable

to the modern hobby

of

model trains

.

Mythological

and ceremonial use

The bigae of

Achilles

and

Memnon

, each drawn by one white

horse and one black horse (hydria,

575–550 BC)

In his

Etymologies

,

Isidore of Seville

explains the cosmic

symbolism of chariot racing, and notes that while the

quadriga

, or four-horse chariot, represents

the sun and its course through the four seasons, the biga represents the

moon, “because it travels on a twin course with the sun, or because it is

visible both by day and by night — for they yoke together one black horse and

one white.” Chariots frequently appear in Roman art as allegories of the Sun and

Moon, particularly in

reliefs

and

mosaics

, in contexts that are readily

distinguishable from depictions of real-world charioteers in the circus.

Luna in her biga drawn by horses or oxen was an element of

Mithraic

iconography, usually in the context of

the tauroctony

. In the

mithraeum

of S. Maria Capua Vetere, a wall

painting that uniquely focuses on Luna alone shows one of the horses of the team

as light in color, with the other a dark brown. It has been suggested that the

duality of the horses drawing a biga can also represent

Plato

‘s

metaphor

of the charioteer who must control a

soul divided by genesis and apogenesis.

Greek

and

Roman art

depicts deities driving two-yoke

chariots drawn by a number of animals. A biga of oxen was driven by

Hecate

, the

chthonic

aspect of the Triple Goddess in

complement with the “horned” or crescent-crowned

Diana

and

Luna

, to whom the biga was sacred.

Triptolemus

is depicted on Roman coins as

driving a serpent-drawn biga as he sows grain in response to

Demeter’s

appeal to him to teach mankind the

skill of agriculture, such as on an Alexandrine

drachma

,

see

.

In his chapter on gemstones,

Pliny

records a ritualized use of the biga,

saying those who seek the draconitis or draconitias, “snake

stone”, ride in a biga.[26]

Bigatus

Boys acting out chariot races with a cart pulled by two large birds,

possibly herons or ostriches (mosaic,

Villa del Casale

, c. 300 AD)

The bigatus

was a silver coin so called because

it depicted a biga. Luna in her two-horse chariot was depicted on the

first issue of the

bigatus

.

Victory

in her biga was later featured.

|