|

Greek city of

Pantikapaion

in

Tauric Chersonesos

Bronze 18mm (2.91 grams) Struck circa 3rd-2nd Century B.C.

Reference: Sear 1705; B.M.C.3.39,40

Bearded head of

Pan

left, wreathed with ivy.

ΠANTI,

Cornucopia

between caps of the

Dioscuri

.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

The cornucopia (from Latin cornu copiae) or horn of plenty

is a symbol of abundance and nourishment, commonly a large horn-shaped container

overflowing with produce, flowers, nuts, other edibles, or wealth in some form.

Originating in

classical antiquity

, it has continued as a

symbol in

Western art

, and it is particularly associated

with the

Thanksgiving

holiday in

North America

.

Allegorical

depiction of the Roman

goddess

Abundantia

with a cornucopia, by

Rubens

(ca. 1630)

In Mythology

Mythology

offers multiple

explanations of the origin

of the cornucopia.

One of the best-known involves the birth and nurturance of the infant

Zeus, who had to be hidden from his devouring father

Cronus

. In a cave on

Mount Ida

on the island of

Crete

, baby Zeus was cared for and protected by

a number of divine attendants, including the goat

Amalthea

(“Nourishing Goddess”), who fed him

with her milk. The suckling future king of the gods had unusual abilities and

strength, and in playing with his nursemaid accidentally broke off one of her

horns

, which then had the divine power to

provide unending nourishment, as the foster mother had to the god.

In another myth, the cornucopia was created when

Heracles

(Roman

Hercules

) wrestled with the river god

Achelous

and wrenched off one of his horns;

river gods were sometimes depicted as horned. This version is represented in the

Achelous and Hercules

mural painting

by the

American Regionalist

artist

Thomas Hart Benton

.

The cornucopia became the attribute of several

Greek

and

Roman deities

, particularly those associated

with the harvest, prosperity, or spiritual abundance, such as personifications

of Earth (Gaia

or

Terra

); the child

Plutus

, god of riches and son of the grain

goddess Demeter

; the

nymph

Maia

; and

Fortuna

, the goddess of luck, who had the power

to grant prosperity. In

Roman Imperial cult

, abstract Roman deities who

fostered peace (pax

Romana) and prosperity were also depicted with a cornucopia,

including Abundantia

, “Abundance” personified, and

Annona

, goddess of the

grain supply to the city of Rome

.

Pluto

, the classical ruler of the underworld in

the

mystery religions

, was a giver of agricultural,

mineral and spiritual wealth, and in art often holds a cornucopia to distinguish

him from the gloomier Hades

, who holds a

drinking horn

instead.

Modern depictions

In modern depictions, the cornucopia is typically a hollow, horn-shaped

wicker basket filled with various kinds of festive

fruit

and

vegetables

. In North America, the cornucopia

has come to be associated with

Thanksgiving

and the harvest. Cornucopia is

also the name of the annual November Wine and Food celebration in

Whistler

, British Columbia, Canada. Two

cornucopias are seen in the

flag

and

state seal

of

Idaho

. The Great

Seal

of

North Carolina

depicts Liberty standing and

Plenty holding a cornucopia. The coat of arms of

Colombia

,

Panama

,

Peru and

Venezuela

, and the Coat of Arms of the State of

Victoria, Australia

, also feature the

cornucopia, symbolising prosperity.

The horn of plenty is used on body art and at Halloween, as it is a symbol of

fertility, fortune and abundance.

-

Base of a statue of

Louis XV of France

In

Greek religion

and

mythology

, Pan (Ancient

Greek: Πᾶν, Pān) is the

god of the wild, shepherds and flocks, nature of mountain wilds, hunting and

rustic music

, and companion of the

nymphs

.[1]

His name originates within the

Ancient Greek

language, from the word paein

(πάειν), meaning “to pasture.”[2]

He has the hindquarters, legs, and horns of a goat, in the same manner as a

faun or satyr

. With his homeland in rustic

Arcadia

, he is recognized as the god of fields,

groves, and wooded glens; because of this, Pan is connected to fertility and the

season of spring. The ancient Greeks also considered Pan to be the god of

theatrical criticism.

The god Pan is said to have intervened on behalf of the

Macedonians in Antiogonos’ battle

with the Gauls in 277 B.C.

In

Roman religion and myth

, Pan’s counterpart was

Faunus

, a nature god who was the father of

Bona Dea

, sometimes identified as

Fauna

. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Pan

became a significant figure in

the Romantic movement

of western Europe, and

also in the 20th-century

Neopagan movement

.

Origins

In his earliest appearance in literature,

Pindar

‘s Pythian Ode iii. 78, Pan is associated

with a

mother goddess

, perhaps

Rhea

or

Cybele

; Pindar refers to virgins worshipping

Cybele

and Pan near the poet’s house in

Boeotia

.

The parentage of Pan is unclear; in some

myths

he is the son of

Zeus, though generally he is the son of

Hermes

or

Dionysus

, with whom his mother is said to be a

nymph

, sometimes

Dryope

or, in

Nonnus

, Dionysiaca (14.92), Penelope of

Mantineia

in Arcadia. This nymph at some point

in the tradition became conflated with

Penelope

, the wife of

Odysseus

.

Pausanias

8.12.5 records the story that

Penelope had in fact been unfaithful to her husband, who banished her to

Mantineia upon his return. Other sources (Duris

of Samos; the Vergilian commentator

Servius

) report that Penelope slept with all

108 suitors in Odysseus’ absence, and gave birth to Pan as a result. This myth

reflects the folk etymology that equates Pan’s name (Πάν) with the Greek word

for “all” (πᾶν). It is more likely to be

cognate

with paein, “to pasture”, and to

share an origin with the modern English word “pasture”. In 1924, Hermann Collitz

suggested that Greek Pan and Indic

Pushan

might have a common Indo-European

origin. In the

Mystery cults

of the highly syncretic

Hellenistic

era Pan is made cognate with

Phanes/Protogonos

,

Zeus,

Dionysus

and

Eros

.

The

Roman

Faunus

, a god of Indo-European origin, was

equated with Pan. However, accounts of Pan’s genealogy are so varied that it

must lie buried deep in mythic time. Like other nature spirits, Pan appears to

be older than the

Olympians

, if it is true that he gave

Artemis

her hunting dogs and taught the secret

of prophecy to Apollo

. Pan might be multiplied as the Panes

(Burkert 1985, III.3.2; Ruck and Staples 1994 p 132) or the Paniskoi.

Kerenyi (p. 174) notes from

scholia

that

Aeschylus

in Rhesus distinguished

between two Pans, one the son of Zeus and twin of

Arcas

, and one a son of

Cronus

. “In the retinue of

Dionysos

, or in depictions of wild landscapes,

there appeared not only a great Pan, but also little Pans, Paniskoi, who played

the same part as the Satyrs

“.

Worship

The worship of Pan began in

Arcadia

which was always the principal seat of

his worship. Arcadia was a district of mountain people whom other Greeks

disdained. Greek hunters used to scourge the statue of the god if they had been

disappointed in the chase (Theocritus. vii. 107). Being a rustic god, Pan was

not worshipped in temples or other built edifices, but in natural settings,

usually caves

or

grottoes

such as the one on the north slope of

the

Acropolis of Athens

. These are often referred

to as the Cave of Pan

. The only exceptions are the

Temple of Pan

on the

Neda River

gorge in the southwestern

Peloponnese

– the ruins of which survive to

this day – and the Temple of Pan at

Apollonopolis Magna in

ancient Egypt

.

Mythology

Greek deities

series |

|

Primordial deities

|

Titans

and

Olympians

|

|

Aquatic deities

|

|

Chthonic deities

|

|

Personified concepts

|

| Other deities |

- Anemoi

-

Asclepius

-

Iris

- Leto

|

|

The goat-god Aegipan

was nurtured by

Amalthea

with the infant

Zeus in Athens. In Zeus’ battle with

Gaia

, Aegipan and

Hermes

stole back Zeus’ “sinews” that

Typhon

had hidden away in the

Corycian Cave

. Pan aided his foster-brother in

the battle with the Titans

by letting out a

horrible screech and scattering them in terror. According to some traditions,

Aegipan

was the son of Pan, rather than his

father.

One of the famous myths of Pan involves the origin of his

pan flute

, fashioned from lengths of hollow

reed. Syrinx

was a lovely water-nymph

of Arcadia, daughter of Landon, the river-god. As she was returning from the

hunt one day, Pan met her. To escape from his importunities, the fair nymph ran

away and didn’t stop to hear his compliments. He pursued from Mount Lycaeum

until she came to her sisters who immediately changed her into a reed. When the

air blew through the reeds, it produced a plaintive melody. The god, still

infatuated, took some of the reeds, because he could not identify which reed she

became, and cut seven pieces (or according to some versions, nine), joined them

side by side in gradually decreasing lengths, and formed the musical instrument

bearing the name of his beloved

Syrinx

. Henceforth Pan was seldom seen without

it.

Echo

was a nymph who was a great singer and

dancer and scorned the love of any man. This angered Pan, a

lecherous god, and he instructed his followers to kill her. Echo was

torn to pieces and spread all over earth. The goddess of the earth,

Gaia

, received the pieces of Echo, whose voice

remains repeating the last words of others. In some versions, Echo and Pan had

two children: Iambe

and

Iynx. In other versions, Pan had fallen in love with Echo, but she

scorned the love of any man but was enraptured by Narcissus. As Echo was cursed

by Hera to only be able to repeat words that had been said by someone else, she

could not speak for herself. She followed Narcissus to a pool, where he fell in

love with his own reflection and changed into a narcissus flower. Echo wasted

away, but her voice could still be heard in caves and other such similar places.

Pan also loved a nymph named

Pitys

, who was turned into a pine tree to

escape him.

Disturbed in his secluded afternoon naps, Pan’s angry shout inspired

panic

(panikon deima) in lonely

placesFollowing the Titans’ assault on

Olympus

, Pan claimed credit for the victory of

the gods because he had frightened the attackers. In the

Battle of Marathon

(490 BC), it is said that

Pan favored the Athenians and so inspired panic in the hearts of their enemies,

the Persians

Erotic aspects

Pan with a goat, statue from

Villa of the Papyri

,

Herculaneum

.

Pan is famous for his sexual powers, and is often depicted with a

phallus

.

Diogenes of Sinope

, speaking in jest, related a

myth of Pan learning

masturbation

from his father,

Hermes

, and teaching the habit to shepherds.

Pan’s greatest conquest was that of the moon goddess

Selene

. He accomplished this by wrapping

himself in a

sheepskin

to hide his hairy black goat form,

and drew her down from the sky into the forest where he seduced her.

Pan and music

In two late Roman sources,

Hyginus

and

Ovid, Pan is substituted for the satyr

Marsyas

in the theme of a musical competition (agon),

and the punishment by flaying is omitted.

Pan once had the audacity to compare his music with that of

Apollo

, and to challenge Apollo, the god of the

lyre, to a trial of skill.

Tmolus

, the mountain-god, was chosen to umpire.

Pan blew on his pipes and gave great satisfaction with his rustic melody to

himself and to his faithful follower,

Midas

, who happened to be present. Then Apollo

struck the strings of his lyre. Tmolus at once awarded the victory to Apollo,

and all but Midas agreed with the judgment. Midas dissented and questioned the

justice of the award. Apollo would not suffer such a depraved pair of ears any

longer and turned Midas’ ears into those of a

donkey

.

In another version of the myth, the first round of the contest was a tie, so

the competitors were forced to hold a second round. In this round, Apollo

demanded that they play their instruments upside-down. Apollo, playing the lyre,

was unaffected. However, Pan’s pipe could not be played while upside down, so

Apollo won the contest.

Capricornus

The

constellation

Capricornus

is traditionally depicted as a

sea-goat, a goat with a fish’s tail (see

“Goatlike” Aigaion called Briareos, one of the

Hecatonchires

). A myth reported as “Egyptian” in

Gaius Julius Hyginus

‘ Poetic Astronomy[22]

that would seem to be invented to justify a connection of Pan with Capricorn

says that when Aegipan

— that is Pan in his goat-god aspect —

was attacked by the monster

Typhon

, he dove into the Nile; the parts above

the water remained a goat, but those under the water transformed into a fish.

Epithets

Aegocerus “goat-horned” was an epithet of Pan descriptive of his

figure with the horns of a goat.

All of the Pans

Pan could be multiplied into a swarm of Pans, and even be given individual

names, as in Nonnus

‘

Dionysiaca

, where the god Pan had twelve

sons that helped Dionysus in his war against the Indians. Their names were

Kelaineus, Argennon, Aigikoros, Eugeneios, Omester, Daphoineus, Phobos,

Philamnos, Xanthos, Glaukos, Argos, and Phorbas.

Two other Pans were

Agreus

and

Nomios

. Both were the sons of Hermes, Agreus’

mother being the nymph Sose, a prophetess: he inherited his mother’s gift of

prophecy, and was also a skilled hunter. Nomios’ mother was Penelope (not the

same as the wife of Odysseus). He was an excellent shepherd, seducer of nymphs,

and musician upon the shepherd’s pipes. Most of the mythological stories about

Pan are actually about Nomios, not the god Pan. Although, Agreus and Nomios

could have been two different aspects of the prime Pan, reflecting his dual

nature as both a wise prophet and a lustful beast.

Aegipan

, literally “goat-Pan,” was a Pan who

was fully goatlike, rather than half-goat and half-man. When the Olympians fled

from the monstrous giant Typhoeus and hid themselves in animal form, Aegipan

assumed the form of a fish-tailed goat. Later he came to the aid of Zeus in his

battle with Typhoeus, by stealing back Zeus’ stolen sinews. As a reward the king

of the gods placed him amongst the stars as the Constellation Capricorn. The

mother of Aegipan, Aix (the goat), was perhaps associated with the constellation

Capra.

Sybarios was an Italian Pan who was worshipped in the Greek colony of Sybaris

in Italy. The Sybarite Pan was conceived when a Sybarite shepherd boy named

Krathis copulated with a pretty she-goat amongst his herds.

The “Death” of Pan

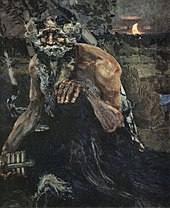

Pan,

Mikhail Vrubel

1900.

According to the Greek historian

Plutarch

(in De defectu oraculorum, “The

Obsolescence of Oracles”), Pan is the only Greek god (other than

Asclepius

) who actually dies. During the reign

of Tiberius

(A.D. 14–37), the news of Pan’s death

came to one Thamus, a sailor on his way to Italy by way of the island of

Paxi. A divine voice hailed him across the salt water, “Thamus, are

you there? When you reach

Palodes

, take care to proclaim that the great

god Pan is dead.” Which Thamus did, and the news was greeted from shore with

groans and laments.

Christian apologists took Plutarch’s notice to heart, and repeated and

amplified it until the 18th century. It was interpreted with

concurrent meanings

exegesisin all four modes of medieval

: literally as historical fact, and

allegorically

as the death of the ancient order

at the coming of the new.[original

research?]

Eusebius of Caesarea

in his

Praeparatio Evangelica

(book V) seems to

have been the first Christian apologist to give Plutarch’s anecdote, which he

identifies as his source pseudo-historical standing, which Eusebius buttressed

with many invented passing details that lent

verisimilitude

. It should be noted that it

would be absurd for medieval Christian apologists to even consider Plutarch’s

account to be historically factual–and not merely a symbolic anecdote–inasmuch

as their Christian monotheistic beliefs would inevitably come into conflict with

Plutarch’s pagan polytheistic account.

In more modern times, some have suggested a possible a naturalistic explanation

for the myth. For example,

Robert Graves

(The Greek Myths) reported

a suggestion that had been made by Salomon Reinach and expanded by James S. Van

Teslaar[29]

that the hearers aboard the ship, including a supposed Egyptian, Thamus,

apparently misheard Thamus Panmegas tethneke ‘the all-great

Tammuz

is dead’ for ‘Thamus, Great Pan is

dead!’, Thamous, Pan ho megas tethneke. “In its true form the phrase

would have probably carried no meaning to those on board who must have been

unfamiliar with the worship of Tammuz which was a transplanted, and for those

parts, therefore, an exotic custom.” Certainly, when

Pausanias

toured Greece about a century after

Plutarch, he found Pan’s shrines, sacred caves and sacred mountains still very

much frequented. However, a naturalistic explanation might not be needed. For

example, William Hansen has shown that the story is quite similar to a class of

widely-known tales known as Fairies Send a Message.

The cry “Great Pan is dead” has appealed to poets, such as

John Milton

, in his ecstatic celebration of

Christian peace,

On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity

line

89, and

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

.

One remarkable commentary of Herodotus on Pan is that he lived 800 years

before himself (c. 1200 BCE), this being already after the Trojan War.

Influence

Revivalist imagery

The Magic of Pan’s Flute, by

John Reinhard Weguelin

(1905)

In the late 18th century, interest in Pan revived among liberal scholars.

Richard Payne Knight

discussed Pan in his

Discourse on the Worship of Priapus (1786) as a symbol of creation expressed

through sexuality. “Pan is represented pouring water upon the organ of

generation; that is, invigorating the active creative power by the prolific

element.”

In the English town of

Painswick

in

Gloucestershire

, a group of 18th century

gentry, led by Benjamin Hyett, organised an annual procession dedicated to Pan,

during which a statue of the deity was held aloft, and people shouted ‘Highgates!

Highgates!” Hyett also erected temples and follies to Pan in the gardens of his

house and a “Pan’s lodge”, located over Painswick Valley. The tradition died out

in the 1830s, but was revived in 1885 by the new vicar, W. H. Seddon, who

mistakenly believed that the festival had been ancient in origin. One of

Seddon’s successors, however, was less appreciative of the pagan festival and

put an end to it in 1950, when he had Pan’s statue buried.

John Keats

‘s

“Endymion”

opens with a festival dedicated to

Pan where a stanzaic hymn is sung in praise of him. “Keats’s account of Pan’s

activities is largely drawn from the Elizabethan poets. Douglas Bush notes, ‘The

goat-god, the tutelary divinity of shepherds, had long been allegorized on

various levels, from Christ to “Universall Nature”

(Sandys)

; here he becomes the symbol of the

romantic imagination, of supra-mortal knowledge.'”

In the late nineteenth century Pan became an increasingly common figure in

literature and art. Patricia Merivale states that between 1890 and 1926 there

was an “astonishing resurgence of interest in the Pan motif”. He appears in

poetry, in novels and children’s books, and is referenced in the name of the

character Peter Pan

. He is the eponymous “Piper at the

Gates of Dawn” in the seventh chapter of

Kenneth Grahame

‘s

The Wind in the Willows

(1908). Grahame’s

Pan, unnamed but clearly recognisable, is a powerful but secretive nature-god,

protector of animals, who casts a spell of forgetfulness on all those he helps.

He makes a brief appearance to help the Rat and Mole recover the Otter’s lost

son Portly.

Arthur Machen

‘s 1894 novella

The Great God Pan

uses the god’s name in a

simile about the whole world being revealed as it really is: “. . . seeing the

Great God Pan”. The novella is considered by many (including

Stephen King

) as being one of the greatest

horror stories ever written.

Pan entices villagers to listen to his pipes as if in a trance in

Lord Dunsany

‘s novel ‘The Blessing of Pan’

published in 1927. Although the god does not appear within the story, his energy

certainly invokes the younger folk of the village to revel in the summer

twilight, and the vicar of the village is the only person worried about the

revival of worship for the old pagan god.

Pan is also featured as a prominent character in

Tom Robbins

‘

Jitterbug Perfume

(1984).

Aeronautical engineer

and

occultist

Jack Parsons

invoked Pan before test launches

at the

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

.

Identification with

Satan

Francisco Goya

,

Witches’ Sabbath (El aquelarre),

. 1798. Oil on canvas, 44 × 31 cm. Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.

Pan’s goatish image recalls conventional

faun-like depictions of

Satan

. Although Christian use of Plutarch’s

story is of long standing[original

research?][citation

needed],

Ronald Hutton

has argued that this specific

association is modern and derives from Pan’s popularity in Victorian and

Edwardian

neopaganism

. Medieval and early modern images

of Satan tend, by contrast, to show generic semi-human monsters with horns,

wings and clawed feet.

Neopaganism

In 1933, the Egyptologist

Margaret Murray

published the book, The God

of the Witches, in which she theorised that Pan was merely one form of a

horned god

who was worshipped across Europe by

a

witch-cult

. This theory influenced the

Neopagan

notion of the Horned God, as an

archetype

of male virility and sexuality. In

Wicca

, the archetype of the Horned God is

highly important, as represented by such deities as the Celtic

Cernunnos

, Indian

Pashupati

and Greek Pan.

A modern account of several purported meetings with Pan is given by

Robert Ogilvie Crombie

in The Findhorn

Garden (Harper & Row, 1975) and The Magic Of Findhorn (Harper & Row,

1975). Crombie claimed to have met Pan many times at various locations in

Scotland, including

Edinburgh

, on the island of

Iona and at the

Findhorn Foundation

.

In classical mythology, Syrinx was a

nymph

and a follower of

Artemis

, known for her

chastity

. Pursued by the amorous Greek god

Pan

, she ran to a river’s edge and asked for

assistance from the river nymphs. In answer, she was transformed into hollow

water reeds

that made a haunting sound when the god’s

frustrated breath blew across them. Pan cut the reeds to fashion the first set

of

pan pipes

, which were thenceforth known as

syrinx. The word syringe was derived from this word.

In literature

The story of the syrinx is told in

Achilles Tatius

‘

Leukippe and Kleitophon

where the heroine

is subjected to a virginity test by entering a cave where Pan has left syrinx

pipes that will sound a melody if she passes. The story became popular among

artists and writers in the 19th century. The Victorian artist and poet

Thomas Woolner

wrote Silenus, a long

narrative poem about the myth, in which Syrinx becomes the lover of

Silenus

, but drowns when she attempts to escape

rape by Pan, as a result of the crime Pan is transmuted into a demon figure and

Silenus becomes a drunkard.

Amy Clampitt

‘s poem Syrinx refers to the

myth by relating the whispering of the reeds to the difficulties of language.

The story was used as a central theme by Aifric Mac Aodha in her poetry

collection “Gabháil Syrinx”.

Samuel R. Delany

features an instrument called

a syrynx in his classic science-fiction novel Nova.

In art

“Pan and Syrinx” by

Jean-François de Troy

The Victorian artist,

Arthur Hacker

(September 25, 1858 – November

12, 1919), depicted Syrinx in his 1892 nude. This painting in oil on canvas is

currently on display in

Manchester Art Gallery

.

Sculptor

Adolph Wolter

was commissioned in 1973 to

create a replacement for a stolen sculpture of

Syrinx

in

Indianapolis

,

Indiana

. This work was a replacement for a

similar statue by

Myra Reynolds Richards

that had been stolen.

The sculpture sits in University Park located in the city’s

Indiana World War Memorial Plaza

.

In music

Claude Debussy

wrote

“Syrinx (La Flute De Pan)”

based on Pan’s

sadness over losing his love. This piece was the first unaccompanied flute solo

of the 20th century[citation

needed], and remains a very popular addition to the

modern flautist’s repertoire. It was also transcribed for solo saxophone,

becoming a standard performance piece for saxophone too. It was used as

incidental music in the play Psyché by Gabriel Mourey.[4]

French Baroque composer Michel Pignolet de Montéclair composed “Pan et Syrinx”,

a cantata for voice & ensemble (No 4 of Second livre de cantates).

Danish composer

Carl Nielsen

composed “Pan

and Syrinx” (Pan og Syrinx), Op. 49, FS 87.

Canadian

electronic

progressive rock

band

Syrinx

took their name from the legend.

Canadian

progressive rock

band

Rush

have a movement titled “The Temples of

Syrinx” in their song “2112”

on their album

2112

. The song is about a

dystopian

futuristic society in which the arts,

particularly music, have been suppressed by the Priests of the Temples of Syrinx.

Panticapaeum (Greek:

Παντικάπαιον, Pantikápaion), present-day

Kerch

: an

important

Greek

city and port in Taurica

(Tauric Chersonese), situated on a hill (Mt.

Mithridates

) on the western side of the

Cimmerian Bosporus

, founded by

Milesians

in

the late 7th–early 6th century BC.

In the 5th–4th centuries BC, the city became the residence first of the

Archaeanactids

and then of the

Spartocids

,

dynasties of

Greek

kings of

Bosporus

, and was hence itself sometimes called Bosporus. Its economic

decline in the 4th–3rd centuries BC was the result of the

Sarmatian

conquest of the steppes and the growing competition of

Egyptian

grain. The last of the

Spartocids

,

Paerisades V

, apparently left his realm to

Mithridates VI

Eupator, king of

Pontus

.

This transition was arranged by one of Mithridates’s generals, a certain

Diophantus

, who earlier was sent to Taurica to help local Greek cities

against Palacus

of

Lesser Scythia

. The takeover didn’t go smoothly: Paerisades was murdered by

Scythians

led by

Saumacus

,

Diophantus

escaped to return later with reinforcements and to suppress the

revolt (c. 110 BC).

Half of a century later, Mithridates himself took his life in Panticapaeum,

when, after his defeat in a

war

against

Rome

,

his own son and heir

Pharnaces

and citizens of Panticapaeum turned against him. In 63 BC the city

was partly destroyed by an earthquake. Raids by the

Goths

and the

Huns furthered its

decline, and it was incorporated into the

Byzantine

state under

Justin I

in

the early 6th century AD.

Ruins of Panticapaeum in

Kerch

(Ukraine)

During the first centuries of the city’s existence, imported Greek articles

predominated: pottery

Kerch

Style), terracottas

, and metal objects, probably from workshops in

Rhodes

,

Corinth

,

Samos

,

and Athens

.

Local production, imitated from the models, was carried on at the same time.

Athens manufactured a special type of bowl for the city, known as

Kerch

ware. Local

potters imitated the

Hellenistic

bowls known as the

Gnathia

style as well as relief wares—Megarian

bowls. The city minted silver coins from the mid 6th century BC and from the 1st

century BC gold and bronze coins. The

Hermitage

and Kerch

Museums contain material from the site, which is still being

excavated.

Bibliography

-

Noonan, Thomas S.

“The Origins of the Greek Colony at Panticapaeum”,

American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 77, No. 1. (1973), pp. 77–81.

|