|

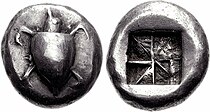

Greek King Philip II of Macedon 359-336 B.C.

Father of Alexander III the Great

Bronze 17mm (5.85 grams) Struck 359-336 B.C. in the Kingdom of Macedonia

Commemorating his Olympic Games Victory

Head of Apollo left, hair bound with tainia.

Nude athlete on horse prancing left, ΦIΛIΠΠΟΥ above.

* Numismatic Note: Authentic ancient Greek coin of King Philip II of Macedonia,

father

of Alexander the Great. Intriguing coin referring to his Olympic victory.

Left Apollo head and left horse are very rare.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

History Behind the Coin

Horse racing was an Olympic event of great prestige and intense competition. It

was a great honor for Philip II of Macedon to gain entry to the games, since

they were open only to Greeks. Prior to that time, the Macedonians were

considered by other Greeks as barbarians. It was an even greater honor for

Philip’s horses to win the prize. In 356 BC his entry won the single horse

event, and in 348 the two horse chariot event. Both of these victories were

proudly announced (should we say propagandized) by placing references to them on

the reverses of his coins struck in gold, silver and bronze. Plutarch tells us

that this was indeed his intention: “[Philip] …had victories of his chariots

at Olympia stamped on his coins.”

In

Greek

and

Roman mythology

, Apollo

,

is one of the most important and diverse of the

Olympian deities

. The ideal of the

kouros

(a

beardless youth), Apollo has been variously recognized as a god of light and the

sun; truth and prophecy;

archery

;

medicine and healing; music, poetry, and the arts; and more. Apollo is the son

of Zeus

and

Leto, and has a

twin

sister, the chaste huntress

Artemis

.

Apollo is known in Greek-influenced

Etruscan mythology

as Apulu. Apollo was worshiped in both

ancient Greek

and

Roman religion

, as well as in the modern

Greco

–Roman

Neopaganism

.

As the patron of Delphi

(Pythian Apollo), Apollo was an

oracular

god — the prophetic deity of the

Delphic Oracle

.

Medicine and healing were associated with Apollo, whether through the god

himself or mediated through his son

Asclepius

,

yet Apollo was also seen as a god who could bring ill-health and deadly

plague

as well as one who had the ability to cure. Amongst the god’s

custodial charges, Apollo became associated with dominion over

colonists

, and as the patron defender of herds and flocks. As the leader of

the Muses

(Apollon

Musagetes) and director of their choir, Apollo functioned as the patron god

of music and poetry

.

Hermes

created

the lyre

for him,

and the instrument became a common

attribute

of Apollo. Hymns sung to Apollo were called

paeans

.

In Hellenistic times, especially during the third century BCE, as Apollo

Helios he became identified among Greeks with

Helios

,

god of

the sun

, and his sister Artemis similarly equated with

Selene

,

goddess

of the moon

.

In Latin texts, on the other hand, Joseph Fontenrose declared himself unable to

find any conflation of Apollo with

Sol

among the

Augustan poets

of the first century, not even in the conjurations of

Aeneas

and

Latinus

in

Aeneid

XII

(161–215).

Apollo and Helios/Sol remained separate beings in literary and mythological

texts until the third century CE.

Philip II of Macedon, (Greek:

Φίλιππος Β’ ο Μακεδών — φίλος

= friend + ίππος =

horse

— transliterated

Philippos 382 – 336 BC, was an ancient

Greek

king (basileus)

of

Macedon

from 359 BC until his assassination in 336. He was the father of

Alexander the Great

and

Philip III

.

Born in

Pella

, Philip was

the youngest son of the king

Amyntas III

and

Eurydice I

. In his youth, (c. 368–365 BC) Philip was held as a hostage in

Thebes

, which was the leading city of

Greece

during

the

Theban hegemony

. While a captive there, Philip received a military and

diplomatic education from

Epaminondas

, became

eromenos

of

Pelopidas

,

and lived with

Pammenes

, who was an enthusiastic advocate of the

Sacred Band of Thebes

. In 364 BC, Philip returned to Macedon. The deaths of

Philip’s elder brothers,

King Alexander II

and

Perdiccas III

, allowed him to take the throne in 359 BC. Originally

appointed regent

for his infant nephew

Amyntas IV

, who was the son of Perdiccas III, Philip managed to take the

kingdom for himself that same year.

Philip’s military skills and expansionist vision of

Macedonian greatness brought him early success. He had however first to

re-establish a situation which had been greatly worsened by the defeat against

the Illyrians

in which King Perdiccas himself had died. The

Paionians

and the

Thracians

had sacked and invaded the eastern regions of the country, while the

Athenians

had

landed, at

Methoni

on the coast, a contingent under a Macedonian pretender called

Argeus

. Using

diplomacy, Philip pushed back Paionians and Thracians promising tributes, and

crushed the 3,000 Athenian

hoplites

(359). Momentarily free from his opponents, he concentrated on strengthening his

internal position and, above all, his army. His most important innovation was

doubtless the introduction of the

phalanx

infantry corps, armed with the famous

sarissa

, an

exceedingly long spear, at the time the most important army corps in Macedonia.

Philip had married

Audata

,

great-granddaughter of the Illyrian king of

Dardania

, Bardyllis

. However, this did not prevent him from marching against them in

358 and crushing them in a ferocious battle in which some 7,000 Illyrians died

(357). By this move, Philip established his authority inland as far as

Lake Ohrid

and the favour of the

Epirotes

.

He also used the

Social War

as an opportunity for expansion. He agreed with the Athenians,

who had been so far unable to conquer

Amphipolis

,

which commanded the

gold

mines

of

Mount Pangaion

, to lease it to them after its conquest, in exchange for

Pydna

(lost by

Macedon in 363). However, after conquering Amphipolis, he kept both the cities

(357). As Athens declared war against him, he allied with the

Chalkidian League

of

Olynthus

.

He subsequently conquered

Potidaea

,

this time keeping his word and ceding it to the League in 356. One year before

Philip had married the

Epirote

princess

Olympias

,

who was the daughter of the king of the

Molossians

.

In 356 BC, Philip also conquered the town of

Crenides

and changed its name to

Philippi

:

he established a powerful garrison there to control its mines, which granted him

much of the gold later used for his campaigns. In the meantime, his general

Parmenion

defeated the Illyrians again. Also in 356

Alexander

was born, and Philip’s race horse won in the

Olympic Games

. In 355–354 he besieged

Methone

, the last city on the

Thermaic Gulf

controlled by Athens. During the siege, Philip lost an eye.

Despite the arrival of two Athenians fleets, the city fell in 354. Philip also

attacked

Abdera

and Maronea, on the

Thracian

seaboard (354–353).

Map of the territory of Philip II of Macedon

Involved in the

Third Sacred War

which had broken out in Greece, in the summer of 353 he

invaded Thessaly

, defeating 7,000

Phocians

under

the brother of Onomarchus. The latter however defeated Philip in the two

succeeding battles. Philip returned to Thessaly the next summer, this time with

an army of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry including all Thessalian troops. In

the

Battle of Crocus Field

6,000 Phocians fell, while 3,000 were taken as

prisoners and later drowned. This battle granted Philip an immense prestige, as

well the free acquisition of

Pherae

. Philip

was also tagus of Thessaly, and he claimed as his own

Magnesia

,

with the important harbour of

Pagasae

.

Philip did not attempt to advance into

Central Greece

because the Athenians, unable to arrive in time to defend

Pagasae, had occupied

Thermopylae

.

Hostilities with Athens did not yet take place, but Athens

was threatened by the Macedonian party which Philip’s gold created in

Euboea

. From

352 to 346 BC, Philip did not again come south. He was active in completing the

subjugation of the

Balkan

hill-country to the west and north, and in reducing the Greek cities of the

coast as far as the

Hebrus

. To

the chief of these coastal cities, Olynthus, Philip continued to profess

friendship until its neighboring cities were in his hands.

In 349 BC, Philip started the siege of Olynthus, which, apart

from its strategic position, housed his relatives

Arrhidaeus

and Menelaus, pretenders to the Macedonian throne. Olynthus had

at first allied itself with Philip, but later shifted its allegiance to Athens.

The latter, however, did nothing to help the city, its expeditions held back by

a revolt in Euboea (probably paid by Philip’s gold). The

Macedonian

king finally took Olynthus in 348 BC and razed the city to the

ground. The same fate was inflicted on other cities of the Chalcidian peninsula.

Macedon and the regions adjoining it having now been securely consolidated,

Philip celebrated his

Olympic Games

at

Dium

. In 347 BC, Philip advanced to the conquest of the eastern districts

about Hebrus, and compelled the submission of the

Thracian

prince

Cersobleptes

. In 346 BC, he intervened effectively in the war between Thebes

and the Phocians, but his wars with Athens continued intermittently. However,

Athens had made overtures for peace, and when Philip again moved south, peace

was sworn in Thessaly. With key Greek city-states in submission, Philip turned

to Sparta

; he

sent them a message, “You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I

bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and

raze your city.” Their

laconic

reply: “If”. Philip and Alexander would both leave them alone.

Later, the Macedonian arms were carried across Epirus to the

Adriatic Sea

. In 342 BC, Philip led a great military expedition north

against the Scythians

, conquering the Thracian fortified settlement Eumolpia to give it

his name, Philippopolis (modern

Plovdiv

).

In 340 BC, Philip started the siege of

Perinthus

. Philip began another siege in 339 of the city of

Byzantium

.

After unsuccessful sieges of both cities, Philip’s influence all over Greece was

compromised. However, he successfully reasserted his authority in the

Aegean

by defeating an alliance of Thebans and Athenians at the

Battle of Chaeronea

in 338 BC, while in the same year, Philip destroyed

Amfissa

because the residents had illegally cultivated part of the Crisaian plain which

belonged to Delphi

.

Philip created and led the

League of Corinth

in 337 BC. Members of the League agreed never to wage war

against each other, unless it was to suppress

revolution

.

Philip was elected as leader (hegemon)

of the army of invasion against the

Persian Empire

. In 336 BC, when the invasion of Persia was in its very early

stage, Philip was assassinated, and was succeeded on the throne of Macedon by

his son

Alexander III

.

Assassination

The murder occurred during October of 336 BC, at

Aegae

, the

ancient capital of the kingdom of Macedon. The court had gathered there for the

celebration of the marriage between

Alexander I of Epirus

and Philip’s daughter, by his fourth wife

Olympias

,

Cleopatra

. While the king was entering unprotected into the town’s theater

(highlighting his approachability to the Greek diplomats present), he was killed

by

Pausanias of Orestis

, one of his seven bodyguards. The assassin immediately

tried to escape and reach his associates who were waiting for him with horses at

the entrance of Aegae. He was pursued by three of Philip’s bodyguards and died

by their hands.

The reasons for Pausanias’ assassination of Phillip are

difficult to fully expound, since there was controversy already among ancient

historians. The only contemporary account in our possession is that of

Aristotle

,

who states rather tersely that Philip was killed because Pausanias had been

offended by the followers of

Attalus

, the king’s father-in-law.

Fifty years later, the historian

Cleitarchus

expanded and embellished the story. Centuries later, this

version was to be narrated by

Diodorus Siculus

and all the historians who used Cleitarchus. In the

sixteenth book of Diodorus’ history, Pausanias had been a lover of Philip, but

became jealous when Philip turned his attention to a younger man, also called

Pausanias. His taunting of the new lover caused the youth to throw away his

life, which turned his friend, Attalus, against Pausanias. Attalus took his

revenge by inviting Pausanias to dinner, getting him drunk, then subjecting him

to sexual assault.

When Pausanias complained to Philip the king felt unable to

chastise Attalus, as he was about to send him to Asia with Parmenion, to

establish a bridgehead for his planned invasion. He also married Attalus’s

niece, or daughter,

Eurydice

. Rather than offend Attalus, Phillip attempted to mollify Pausanius

by elevating him within the bodyguard. Pausanias’ desire for revenge seems to

have turned towards the man who had failed to avenge his damaged honour; so he

planned to kill Philip, and some time after the alleged rape, while Attalus was

already in Asia fighting the Persians, put his plan in action. Other historians

(e.g.,

Justin

9.7) suggested that Alexander and/or his mother

Olympias

were at least privy to the intrigue, if not themselves instigators. The latter

seems to have been anything but discreet in manifesting her gratitude to

Pausanias, if we accept Justin’s report: he tells us that the same night of her

return from exile she placed a crown on the assassin’s corpse and erected a

tumulus to his memory, ordering annual sacrifices to the memory of Pausanias.

The entrance to the “Great Tumulus” Museum at

Vergina

.

Many modern historians have observed that all the accounts

are improbable. In the case of Pausanias, the stated motive of the crime hardly

seems adequate. On the other hand, the implication of Alexander and Olympias

seems specious: to act as they did would have required brazen effrontery in the

face of a military machine personally loyal to Philip. What appears to be

recorded in this are the natural suspicions that fell on the chief beneficiaries

of the murder; their actions after the murder, however sympathetic they might

appear (if actual), cannot prove their guilt in the deed itself. Further

convoluting the case is the possible role of propaganda in the surviving

accounts: Attalus was executed in Alexander’s consolidation of power after the

murder; one might wonder if his enrollment among the conspirators was not for

the effect of introducing political expediency in an otherwise messy purge

(Attalus had publicly declared his hope that Alexander would not succeed Philip,

but rather that a son of his own niece Eurydice, recently married to Philip and

brutally murdered by Olympias after Philip’s death, would gain the throne of

Macedon).

Marriages

The dates of Philip’s multiple marriages and the names of

some of his wives are contested. Below is the order of marriages offered by

Athenaeus, 13.557b-e:

-

Audata

, the

daughter of

Illyrian

King Bardyllis

. Mother of

Cynane

.

-

Phila, the sister of

Derdas

and

Machatas of

Elimiotis

.

-

Nicesipolis

of

Pherae

,

Thessaly

,

mother of

Thessalonica

.

-

Olympias

of

Epirus

, mother of

Alexander the Great

and

Cleopatra

-

Philinna of

Larissa

,

mother of Arrhidaeus later called

Philip III of Macedon

.

-

Meda of Odessa

, daughter of the king Cothelas, of

Thrace

.

-

Cleopatra, daughter of Hippostratus and niece of general

Attalus of Macedonia

. Philip renamed her

Cleopatra Eurydice of Macedon

.

Archaeological

findings

On November 8, 1977, Greek archaeologist

Manolis Andronikos

found, among other royal tombs, an unopened tomb at

Vergina

in

the Greek prefecture of

Imathia

. The finds from this tomb were later included in the traveling

exhibit The Search for Alexander displayed at four cities in the

United States

from 1980 to 1982. Initially identified as belonging to Philip

II, Eugene Borza and others have suggested that the tomb actually belonged to

Philip’s son,

Philip Arrhidaeus

. Disputations often relied on contradictions between “the

body” or “skeleton” of Philip II and reliable historical accounts of his life

(and injuries).

The initial ‘proof’ that the tomb may belong to Philip II was

indicated by the greeves (leg armor to protect the tibia (‘shin’) bone), one of

which indicated that the owner had a leg injury which distorted the natural

alignment of the tibia (Philip II was recorded as having broken his tibia).

What is now viewed as final proof that the tomb indeed did

belong to Philip II and that the surviving bone fragments are in fact the body

of Philip II comes from forensic reconstruction of the scull of Philip II by the

wax casting and reconstruction of the scull which shows the damage to the right

eye caused by the penetration of an object (historically recorded to be an

arrow). See John Prag and Richard Neave’s report in Making Faces: Using Forensic

and Archaeological Evidence, published for the Trustees of the British Museum by

the British Museum Press, London: 1997.

Cult

The

heroon

at

Vergina

in

Greek Macedonia (the ancient city of Aigai – Αἶγαι), is thought to have been

dedicated to the worship of the family of Alexander the Great and may have

housed the cult statue of Philip. It is probable that he was regarded as a hero

or deified on his death. Though the Macedonians did not consider Philip a god,

he did receive other forms of recognition by the Greeks, such as at

Eresos

(altar

to Zeus Philippeios),

Ephesos

(his statue was placed in the

temple of Artemis

), and at Olympia, where the

Philippeion

was built. Moreover, Isocrates wrote to Philip that if he

defeated Persia, there was nothing left for him to do to but become a god

while Demades

proposed that Philip be regarded as the thirteenth god. However, there is no

clear evidence that Philip was raised to divine status like that of his son

Alexander

.

Macedonia or Macedon (from

Greek

: Μακεδονία,

Makedonía) was an

ancient Greek kingdom

. The kingdom, centered in the

northeastern part of the

Greek peninsula

, was bordered by

Epirus

to the west,

Paeonia

to the north, the region of

Thrace

to the east and

Thessaly

to the south. The

rise of Macedon

, from a small kingdom at the

periphery of

Classical Greek

affairs, to one which came to

dominate the entire Hellenic world, occurred under the reign of

Philip II

. For a brief period, after the

conquests of

Alexander the Great

, it became the most

powerful state in the world, controlling a territory that included the former

Persian empire

, stretching as far as the

Indus River

; at that time it inaugurated the

Hellenistic period

of

Ancient Greek civilization

.

Name

The name Macedonia (Greek:

Μακεδονία,

Makedonía) comes from the

ancient Greek word μακεδνός (Makednos).

It is commonly explained as having originally meant “a tall one” or

“highlander”, possibly descriptive of the

people

. The shorter English name variant

Macedon developed in Middle English, based on a borrowing from the French

form of the name, Macédoine.

History

Early history and

legend

The lands around

Aegae

, the first Macedonian capital, were home

to various peoples. Macedonia was called Emathia (from king Emathion) and the

city of Aiges was called Edessa, the capital of fabled king

Midas

in his youth. In approximately 650 BC,

the Argeads

, an ancient Greek royal house led by

Perdiccas I

established their palace-capital at

Aegae.

It seems that the first

Macedonian

state emerged in the 8th or early

7th century BC under the Argead Dynasty, who, according to legend, migrated to

the region from the Greek city

of

Argos

in Peloponnesus (thus the name Argead).

Herodotus mentions this

founding myth

when

Alexander I

was asked to prove his Greek

descent in order to participate in the

Olympic Games

, an athletic event in which only

men of Greek origin were entitled to participate. Alexander proved his (Argead)

descent and was allowed to compete by the

Hellanodikai

: “And that these descendants of

Perdiccas are Greeks, as they themselves say, I happen to know myself, and not

only so, but I will prove in the succeeding history that they are Greeks.

Moreover the Hellanodicai, who manage the games at Olympia, decided that they

were so: for when Alexander wished to contend in the games and had descended for

this purpose into the arena, the Greeks who were to run against him tried to

exclude him, saying that the contest was not for Barbarians to contend in but

for Greeks: since however Alexander proved that he was of Argos, he was judged

to be a Greek, and when he entered the contest of the foot-race his lot came out

with that of the first.” The Macedonian tribe ruled by the Argeads, was itself

called Argead (which translates as “descended from Argos”).

Other founding myths served other agenda: according to Justin’s, Epitome

of the Philippic History of

Pompeius Trogus

, Caranus, accompanied by a

multitude of Greeks came to the area in search for a new homeland took

Edessa and renamed it Aegae. Subsequently, he expelled Midas and other kings and

formed his new kingdom. Conversely, according to

Herodotus

, it was

Dorus, the son of Hellen

who led his people to

Histaeotis, whence they were driven off by the Cadmeians into Pindus, where they

settled as Macedonians. Later, a branch would migrate further south to be called

Dorians.

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers

Haliacmon

and

Axius

, called Lower Macedonia, north of

the mountain

Olympus

. Around the time of

Alexander I of Macedon

, the Argead Macedonians

started to expand into

Upper Macedonia

, lands inhabited by independent

Macedonian tribes like the Lyncestae and the Elmiotae and to the West, beyond

Axius river, into Eordaia

,

Bottiaea

,

Mygdonia

, and

Almopia

, regions settled by, among others, many

Thracian tribes. To the north of Macedonia lay various non-Greek peoples such as

the

Paeonians

due north, the

Thracians

to the northeast, and the

Illyrians

, with whom the Macedonians were

frequently in conflict, to the northwest. To the south lay

Thessaly

, with whose inhabitants the

Macedonians had much in common both culturally and politically, while to west

lay Epirus

, with whom the Macedonians had a

peaceful relationship and in the 4th century BC formed an alliance against

Illyrian raids.

Near the modern city of

Veria

,

Perdiccas I

(or, more likely, his son,

Argaeus I

) built his capital, Aigai (modern

Vergina

). After a brief period under

Persian

rule under

Darius Hystaspes

, the state regained its

independence under King

Alexander I

(495–450

BC). In the

Peloponnesian War

Macedon was a secondary power

that alternated in support between Sparta and Athens.

Involvement in the Classical Greek world

Prior to the 4th century BC, the kingdom covered a region approximately

corresponding to the

Western

and

Central

parts of

province of Macedonia

in modern

Greece

. A unified Macedonian state was

eventually established by King

Amyntas III

(c.

393

–370 BC), though it still retained strong

contrasts between the cattle-rich coastal plain and the fierce isolated tribal

hinterland, allied to the king by marriage ties. They controlled the passes

through which barbarian invasions came from

Illyria

to the north and northwest. It became

increasingly

Atticised

during this period, though prominent

Athenians

appear to have regarded the

Macedonians as uncouth. Before the establishment of the

League of Corinth

, even though the Macedonians

apparently spoke a dialect of the Greek language and claimed proudly that they

were Greeks, they were not considered to fully share the

classical Greek

culture by many of the

inhabitants of the southern city states, because they did not share the

polis

based style of government.

Herodotus

, one of the foremost biographers in

antiquity who lived in Greece at the time when the Macedonian king

Alexander I

was in power, recorded:

“And that these descendants of Perdiccas are Hellenes, as they themselves

say, I happen to know myself, and not only so, but I will prove in the

succeeding history that they are Hellenes. Moreover the

Hellanodikai

, who manage the games at

Olympia, decided that they were so: for when

Alexander

wished to contend in the games

and had descended for this purpose into the arena, the Hellenes who were to

run against him tried to exclude him, saying that the contest was not for

Barbarians to contend in but for Hellenes: since however Alexander proved

that he was of Argos, he was judged to be a Hellene, and when he entered the

contest of the foot-race his lot came out with that of the first.”

Over the 4th century Macedon became more politically involved with the

south-central city-states of

Ancient Greece

, but it also retained more

archaic features like the palace-culture, first at Aegae (modern Vergina) then

at Pella

, resembling

Mycenaean

culture more than classic

Hellenic

city-states, and other archaic

customs, like Philip’s multiple wives in addition to his Epirote queen

Olympias

, mother of Alexander.

Another archaic remnant was the very persistence of a

hereditary

monarchy

which wielded formidable – sometimes

absolute – power, although this was at times checked by the landed aristocracy,

and often disturbed by power struggles within the royal family itself. This

contrasted sharply with the Greek cultures further south, where the ubiquitous

city-states mostly possessed aristocratic or democratic institutions; the

de facto

monarchy of

tyrants

, in which heredity was usually more of

an ambition rather than the accepted rule; and the limited, predominantly

military and sacerdotal, power of the twin hereditary

Spartan

kings. The same might have held true of

feudal

institutions like

serfdom

, which may have persisted in Macedon

well into historical times. Such institutions were abolished by city-states well

before Macedon’s rise (most notably by the Athenian legislator

Solon

‘s famous

σεισάχθεια

seisachtheia

laws).

Rise of Macedon

Philip II

, king of Macedon

Amyntas had three sons; the first two,

Alexander II

and

Perdiccas III

reigned only briefly. Perdiccas

III’s infant heir was deposed by Amyntas’ third son,

Philip II of Macedon

, who made himself king and

ushered in a period of Macedonian dominance in Greece. Under Philip II, (359–336

BC), Macedon expanded into the territory of the

Paeonians

,

Thracians

, and

Illyrians

. Among other conquests, he annexed

the regions of

Pelagonia

and Southern

Paeonia

.

Kingdom of Macedon after Philip’s II death.

Philip redesigned the

army of Macedon

adding a number of variations

to the traditional

hoplite

force to make it far more effective. He

added the

hetairoi

, a well armoured heavy cavalry,

and more light infantry, both of which added greater flexibility and

responsiveness to the force. He also lengthened the spear and shrank the shield

of the main infantry force, increasing its offensive capabilities.

Philip began to rapidly expand the borders of his kingdom. He first

campaigned in the north against non-Greek peoples such as the

Illyrians

, securing his northern border and

gaining much prestige as a warrior. He next turned east, to the territory along

the northern shore of the Aegean. The most important city in this area was

Amphipolis

, which controlled the way into

Thrace

and also was near valuable silver mines.

This region had been part of the

Athenian Empire

, and Athens still considered it

as in their sphere. The Athenians attempted to curb the growing power of

Macedonia, but were limited by the outbreak of the

Social War

. They could also do little to halt

Philip when he turned his armies south and took over most of

Thessaly

.

Control of Thessaly meant Philip was now closely involved in the politics of

central Greece. 356 BC saw the outbreak of the

Third Sacred War

that pitted

Phocis

against

Thebes

and its allies. Thebes recruited the

Macedonians to join them and at the

Battle of Crocus Field

Phillip decisively

defeated Phocis and its Athenian allies. As a result Macedonia became the

leading state in the

Amphictyonic League

and Phillip became head of

the Pythian Games, firmly putting the Macedonian leader at the centre of the

Greek political world.

In the continuing conflict with Athens Philip marched east through Thrace in

an attempt to capture

Byzantium

and the

Bosphorus

, thus cutting off the Black Sea grain

supply that provided Athens with much of its food. The siege of Byzantium

failed, but Athens realized the grave danger the rise of Macedon presented and

under Demosthenes

built a coalition of many of the

major states to oppose the Macedonians. Most importantly Thebes, which had the

strongest ground force of any of the city states, joined the effort. The allies

met the Macedonians at the

Battle of Chaeronea

and were decisively

defeated, leaving Philip and the Macedonians the unquestioned master of Greece.

Empire

Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion

Philip’s son,

Alexander the Great

(356–323

BC), managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the central Greek

city-states by becoming

Hegemon

of the

League of Corinth

(also known as the “Hellenic

League”), but also to the

Persian empire

, including

Egypt

and lands as far east as the fringes of

India

. Alexander helped spread the Greek

culture and learning through his vast empire. Although the empire fractured into

multiple Hellenic regimes shortly after his death, his conquests left a lasting

legacy, not least in the new Greek-speaking cities founded across Persia’s

western territories, heralding the

Hellenistic

period. In the partition of

Alexander’s empire among the

Diadochi

, Macedonia fell to the

Antipatrid dynasty

, which was overthrown by the

Antigonid dynasty

after only a few years, in

294 BC.

Hellenistic era

Antipater

and his son

Cassander

gained control of Macedonia but it

slid into a long period of civil strife following Cassander’s death in 297 BC.

It was ruled for a while by

Demetrius I

(294–288

BC) but fell into civil war.

Demetrius’ son,

Antigonus II

(277–239

BC), defeated a Galatian

invasion as a

condottiere

, and regained his family’s

position in Macedonia; he successfully restored order and prosperity there,

though he lost control of many of the Greek city-states. He established a stable

monarchy under the

Antigonid dynasty

.

Antigonus III

(239–221

BC) built on these gains by re-establishing Macedonian power across the region.

What is notable about the Macedonian regime during the Hellenistic times is

that it was the only successor state to the Empire that maintained the old

archaic perception of kingship, and never adopted the ways of the Hellenistic

monarchy. Thus the king was never deified in the same way that Ptolemies and

Seleucids were in Egypt and Asia respectively, and never adopted the custom of

Proskynesis

. The ancient Macedonians during the

Hellenistic times were still addressing their kings in a far more casual way

than the subjects of the rest of the Diadochi, and the kings were still

consulting with their aristocracy (Philoi) in the process of making their

decisions.

Conflict with Rome

Under

Philip V of Macedon

(221–179

BC) and his son

Perseus of Macedon

(179–168

BC), the kingdom clashed with the rising power of the

Roman Republic

. During the 2nd and 1st

centuries BC, Macedon fought a

series of wars

with Rome. Two major losses that

led to the end of the kingdom were in 197 BC when Rome defeated Philip V, and

168 BC when Rome defeated Perseus. The overall losses resulted in the defeat of

Macedon, the deposition of the Antigonid dynasty and the dismantling of the

Macedonian kingdom.

Andriscus

‘ brief success at reestablishing the

monarchy in 149 BC was quickly followed by his defeat the following year and the

establishment of direct

Roman

rule and the organization of Macedon as

the

Roman province of Macedonia

.

Institutions

The political organization of the Macedonian kingdom was a three-level

pyramid: on the top, the King and the nation, at the foot, the civic

organizations (cities and éthnē), and between the two, the districts. The

study of these different institutions has been considerably renewed thanks to

epigraphy

, which has given us the possibility

to reread the indications given us by ancient literary sources such as

Livy and

Polybius

. They show that the Macedonian

institutions were near to those of the Greek federal states, like the

Aetolian

and

Achaean

leagues, whose unity was reinforced by

the presence of the king.

The

Vergina Sun

, the 16-ray star

covering what appears to be the royal burial larnax of Philip II of

Macedon, discovered in Vergina, Greece.

The King

The king

(Βασιλεύς,

Basileús) headed the

central administration: he led the kingdom from its capital, Pella, and in his

royal palace was conserved the state’s archive. He was helped in carrying out

his work by the

Royal Secretary

(βασιλικὸς

γραμματεύς, basilikós

grammateús), whose work was of primary importance, and by the

Council

. The title “king” (basileús) may

have not officially been used by the Macedonian regents until

Alexander the Great

, whose “usage of it may

have been influenced by his ambivalent position in Persia.”

The king was commander of the army, head of the Macedonian religion, and

director of diplomacy. Also, only he could conclude treaties, and, until

Philip V

, mint coins.

The number of civil servants was limited: the king directed his kingdom

mostly in an indirect way, supporting himself principally through the local

magistrates, the epistates, with whom he constantly kept in touch.

Succession

Royal succession in Macedon was hereditary, male,

patrilineal

and generally respected the

principle of

primogeniture

. There was also an elective

element: when the king died, his designated heir, generally but not always the

eldest son, had first to be accepted by the council and then presented to the

general Assembly to be acclaimed king and obtain the oath of fidelity.

As can be seen, the succession was far from being automatic, more so

considering that many Macedonian kings died violently, without having made

dispositions for the succession, or having assured themselves that these would

be respected. This can be seen with

Perdiccas III

, slain by the

Illyrians

,

Philip II

assassinated by

Pausanias of Orestis

,

Alexander the Great

, suddenly died of malady,

etc. Succession crises were frequent, especially up to the 4th century BC, when

the magnate families of Upper Macedonia still cultivated the ambition of

overthrowing the Argaead dynasty and to ascend to the throne.

An atrium with a pebble-mosaic paving, in Pella, Greece

Finances

The king was the simple guardian and administrator of the treasure of Macedon

and of the king’s incomes (βασιλικά,

basiliká), which belonged

to the Macedonians: and the tributes that came to the kingdom thanks to the

treaties with the defeated people also went to the Macedonian people, and not to

the king. Even if the king was not accountable for his management of the

kingdom’s entries, he may have felt responsible to defend his administration on

certain occasions: Arrian

tells us that during the

mutiny

of Alexander’s soldiers at

Opis in 324 BC, Alexander detailed the possessions of his father at

his death to prove he had not abused his charge.

It is known from Livy and Polybius that the basiliká included the

following sources of income:

- The mines of gold and silver (for example those of the

Pangaeus

), which were the exclusive

possession of the king, and which permitted him to strike currency, as

already said his sole privilege till Philip V, who conceded to cities and

districts the right of coinage for the lesser denominations, like bronze.

- The forests, whose timber was very appreciated by the Greek

cities to build their ships: in particular, it is known that

Athens

made commercial treaties with

Macedon in the 5th century BC to import the timber necessary for the

construction and the maintenance of its fleet of war.

- The royal landed properties, lands that were annexed to the royal

domain through conquest, and that the king exploited either directly, in

particular through servile workforce made up of prisoners of war, or

indirectly through a leasing system.

- The port duties on commerce (importation and exportation taxes).

The most common way to exploit these different sources of income was by

leasing: the Pseudo-Aristotle

reports in the

Oeconomica

that

Amyntas III

(or maybe Philip II) doubled the

kingdom’s port revenues with the help of

Callistratus

, who had taken refuge in Macedon,

bringing them from 20 to 40

talents

per year. To do this, the exploitation

of the harbour taxes was given every year at the private offering the highest

bidding. It is also known from Livy that the mines and the forests were leased

for a fixed sum under Philip V, and it appears that the same happened under the

Argaead dynasty: from here possibly comes the leasing system that was used in

Ptolemaic Egypt

.

Except for the king’s properties, land in Macedon was free: Macedonians were

free men and did not pay land taxes on private grounds. Even extraordinary taxes

like those paid by the Athenians in times of war did not exist. Even in

conditions of economic peril, like what happened to Alexander in 334 BC and

Perseus in 168 BC, the monarchy did not tax its subjects but raised funds

through loans, first of all by his Companions, or raised the cost of the leases.

The king could grant the atelíē (ἀτελίη),

a privilege of tax exemption, as Alexander did with those Macedonian families

which had losses in the

battle of the Granicus

in May

334

: they were exempted from paying tribute for

leasing royal grounds and commercial taxes.

Extraordinary incomes came from the spoils of war, which were divided between

the king and his men. At the time of Philip II and Alexander, this was a

considerable source of income. A considerable part of the gold and silver

objects taken at the time of the European and Asian campaigns were melted in

ingots and then sent to the monetary foundries of

Pella

and

Amphipolis

, most active of the kingdom at that

time: an estimate judges that during the reign of Alexander only the mint of

Amphipolis struck about 13 million silver

tetradrachms

.

The Assembly

All the kingdom’s citizen-soldiers gather in a popular assembly, which is

held at least twice a year, in spring and in autumn, with the opening and the

closing of the campaigning season.

This assembly (koinê ekklesia

or koinon makedonôn), of

the army in times of war, of the people in times of peace, is called by the king

and plays a significant role through the acclamation of the kings and in capital

trials; it can be consulted (without obligation) for the foreign politics

(declarations of war, treaties) and for the appointment of high state officials.

In the majority of these occasions, the Assembly does nothing but ratify the

proposals of a smaller body, the Council. It is also the Assembly which votes

the honors, sends embassies, during its two annual meetings. It was abolished by

the Romans

at the time of their reorganization of

Macedonia in 167 BC, to prevent, according to

Livy, that a demagogue could make use of it as a mean to revolt

against their authority.

Council (Synedrion)

The Council was a small group formed among some of the most eminent

Macedonians, chosen by the king to assist him in the government of the kingdom.

As such it was not a representative assembly, but notwithstanding that on

certain occasions it could be expanded with the admission of representatives of

the cities and of the civic corps of the kingdom.

The members of the Council (synedroi) belong to three categories:

- The

somatophylakes

(in Greek literally

“bodyguards”) were noble Macedonians chosen by the king to serve to him as

honorary bodyguards, but especially as close advisers. It was a particularly

prestigious honorary title. In the times of Alexander there were seven of

them.

- The Friends (philoi)

or the king’s Companions (basilikoi

hetairoi

) were named for life by the

king among the Macedonian aristocracy.

- The most important generals of the army (hégémones tôn taxéôn),

also named by the king.

The king had in reality less power in the choice of the members of the

Council than appearances would warrant; this was because many of the kingdom’s

most important noblemen were members of the Council by birth-right.

The Council primarily exerted a probouleutic function with respect to the

Assembly: it prepared and proposed the decisions which the Assembly would have

discussed and voted, working in many fields such as the designation of kings and

regents, as of that of the high administrators and the declarations of war. It

was also the first and final authority for all the cases which did not involve

capital punishment.

The Council gathered frequently and represented the principal body of

government of the kingdom. Any important decision taken by the king was

subjected before it for deliberation.

Inside the Council ruled the democratic principles of iségoria

(equality of word) and of parrhésia (freedom of speech), to which even

the king subjected himself.

After the removal of the

Antigonid dynasty

by the Romans in 167 BC, it

is possible that the synedrion remained, unlike the Assembly, representing the

sole federal authority in Macedonia after the country’s division in four

merides.

Regional

districts (Merides)

The creation of an intermediate territorial administrative level between the

central government and the cities should probably be attributed to Philip II:

this reform corresponded with the need to adapt the kingdom’s institutions to

the great expansion of Macedon under his rule. It was no longer practical to

convene all the Macedonians in a single general assembly, and the answer to this

problem was the creation of four regional districts, each with a regional

assembly. These territorial divisions clearly did not follow any historical or

traditional internal divisions; they were simply artificial administrative

lines.

This said, it should be noted that the existence of these districts is not

attested with certainty (by

numismatics

) before the beginning of the 2nd

century BC.

The history of

Ancient Greek

coinage can be divided (along

with most other Greek art forms) into four periods, the

Archaic

, the

Classical

, the

Hellenistic

and the

Roman

. The Archaic period extends from the

introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the

7th century BC

until the

Persian Wars

in about 480 BC. The Classical

period then began, and lasted until the conquests of

Alexander the Great

in about 330 BC, which

began the Hellenistic period, extending until the

Roman

absorption of the Greek world in the 1st

century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several

more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are

called

Roman provincial coins

or Greek Imperial Coins.

Ancient Greek coins of all four periods span over a period of more than ten

centuries.

Weight

standards and denominations

Above: Six rod-shaped obeloi (oboloi) displayed at the

Numismatic Museum of Athens

,

discovered at

Heraion of Argos

. Below: grasp[1]

of six oboloi forming one drachma

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC, known as

Phanes’ coin

. Obverse:

Stag

grazing, ΦΑΝΕΩΣ (retrograde).

Reverse: Two incuse punches.

The basic standards of the Ancient Greek monetary system were the

Attic

standard, based on the Athenian

drachma

of 4.3 grams of silver and the

Corinthian

standard based on the

stater

of 8.6 grams of silver, that was

subdivided into three silver drachmas of 2.9 grams. The word

drachm

(a) means “a handful”, literally “a

grasp”. Drachmae were divided into six

obols

(from the Greek word for a

spit

), and six spits made a “handful”. This

suggests that before coinage came to be used in Greece, spits in

prehistoric times

were used as measures of

daily transaction. In archaic/pre-numismatic times iron was valued for making

durable tools and weapons, and its casting in spit form may have actually

represented a form of transportable

bullion

, which eventually became bulky and

inconvenient after the adoption of precious metals. Because of this very aspect,

Spartan

legislation famously forbade issuance

of Spartan coin, and enforced the continued use of iron spits so as to

discourage avarice and the hoarding of wealth. In addition to its original

meaning (which also gave the

euphemistic

diminutive

“obelisk“,

“little spit”), the word obol (ὀβολός, obolós, or ὀβελός,

obelós) was retained as a Greek word for coins of small value, still used as

such in Modern Greek

slang (όβολα, óvola,

“monies”).

The obol was further subdivided into tetartemorioi (singular

tetartemorion) which represented 1/4 of an obol, or 1/24 of a drachm. This

coin (which was known to have been struck in

Athens

,

Colophon

, and several other cities) is

mentioned by Aristotle

as the smallest silver coin.:237

Various multiples of this denomination were also struck, including the

trihemitetartemorion (literally three half-tetartemorioi) valued at 3/8 of

an obol.:

| Denominations of silver drachma |

| Image |

Denomination |

Value |

Weight |

|

|

Dekadrachm |

10 drachmas |

43 grams |

|

|

Tetradrachm |

4 drachmas |

17.2 grams |

|

|

Didrachm |

2 drachmas |

8.6 grams |

|

|

Drachma |

6 obols |

4.3 grams |

|

|

Tetrobol |

4 obols |

2.85 grams |

|

|

Triobol (hemidrachm) |

3 obols |

2.15 grams |

|

|

Diobol |

2 obols |

1.43 grams |

|

|

Obol |

4 tetartemorions |

0.72 grams |

|

|

Tritartemorion |

3 tetartemorions |

0.54 grams |

|

|

Hemiobol |

2 tetartemorions |

0.36 grams |

|

|

Trihemitartemorion |

3/2 tetartemorions |

0.27 grams |

|

|

Tetartemorion |

|

0.18 grams |

|

|

Hemitartemorion |

½ tetartemorion |

0.09 grams |

Archaic period

Archaic coinage

Uninscribed

electrum

coin from

Lydia

, 6th century BCE.

Obverse: lion head and sunburst Reverse: plain square

imprints, probably used to standardise weight

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC. Obverse:

Forepart of stag. Reverse: Square incuse punch.

The first coins were issued in either Lydia or Ionia in Asia Minor at some

time before 600 BC, either by the non-Greek Lydians for their own use or perhaps

because Greek mercenaries wanted to be paid in precious metal at the conclusion

of their time of service, and wanted to have their payments marked in a way that

would authenticate them. These coins were made of

electrum

, an alloy of gold and silver that was

highly prized and abundant in that area. By the middle of the 6th century BC,

technology had advanced, making the production of pure gold and silver coins

simpler. Accordingly, King

Croesus

introduced a bi-metallic standard that

allowed for coins of pure gold and pure silver to be struck and traded in the

marketplace.

Coins of Aegina

Silver

stater

of Aegina, 550-530 BC.

Obv.

Sea turtle

with large pellets

down center. Rev. incuse square with eight sections. After the

end of the

Peloponnesian War

, 404 BC, Sea

turtle was replaced by the land

tortoise

.

Silver

drachma

of Aegina, 404-340 BC.

Obverse: Land

tortoise

. Reverse: inscription

AΙΓ[INAΤΟΝ] ([of the] Aeg[inetans]) “Aegina” and dolphin.

The Greek world was divided into more than two thousand self-governing

city-states (in

Greek

, poleis), and more than half of

them issued their own coins. Some coins circulated widely beyond their polis,

indicating that they were being used in inter-city trade; the first example

appears to have been the silver stater or didrachm of

Aegina

that regularly turns up in hoards in

Egypt

and the

Levant

, places which were deficient in silver

supply. As such coins circulated more widely, other cities began to mint coins

to this “Aeginetan” weight standard of (6.1 grams to the drachm), other cities

included their own symbols on the coins. This is not unlike present day

Euro coins, which are recognisably from a particular country, but

usable all over the

Euro zone

.

Athenian coins, however, were struck on the “Attic” standard, with a drachm

equaling 4.3 grams of silver. Over time, Athens’ plentiful supply of silver from

the mines at

Laurion

and its increasing dominance in trade

made this the pre-eminent standard. These coins, known as “owls” because of

their central design feature, were also minted to an extremely tight standard of

purity and weight. This contributed to their success as the premier trade coin

of their era. Tetradrachms on this weight standard continued to be a widely used

coin (often the most widely used) through the classical period. By the time of

Alexander the Great

and his

Hellenistic successors

, this large denomination

was being regularly used to make large payments, or was often saved for

hoarding.

Classical period

A

Syracusan

tetradrachm

(c. 415–405

BC)

Obverse: head of the

nymph

Arethusa

, surrounded by

four swimming

dolphins

and a

rudder

Reverse: a racing

quadriga

, its

charioteer

crowned by the

goddess

Victory

in flight.

Tetradrachm of Athens, (5th century BC)

Obverse: a portrait of

Athena

, patron goddess of

the city, in

helmet

Reverse: the owl of Athens, with an

olive

sprig and the

inscription “ΑΘΕ”, short for ΑΘΕΝΑΙΟΝ, “of the

Athenians

“

The

Classical period

saw Greek coinage reach a high

level of technical and aesthetic quality. Larger cities now produced a range of

fine silver and gold coins, most bearing a portrait of their patron god or

goddess or a legendary hero on one side, and a symbol of the city on the other.

Some coins employed a visual pun: some coins from

Rhodes

featured a

rose, since the Greek word for rose is rhodon. The use of

inscriptions on coins also began, usually the name of the issuing city.

The wealthy cities of Sicily produced some especially fine coins. The large

silver decadrachm (10-drachm) coin from

Syracuse

is regarded by many collectors as the

finest coin produced in the ancient world, perhaps ever. Syracusan issues were

rather standard in their imprints, one side bearing the head of the nymph

Arethusa

and the other usually a victorious

quadriga

. The

tyrants of Syracuse

were fabulously rich, and

part of their

public relations

policy was to fund

quadrigas

for the

Olympic chariot race

, a very expensive

undertaking. As they were often able to finance more than one quadriga at a

time, they were frequent victors in this highly prestigious event.

Syracuse was one of the epicenters of numismatic art during the classical

period. Led by the engravers Kimon and Euainetos, Syracuse produced some of the

finest coin designs of antiquity.

Hellenistic period

Gold 20-stater

of

Eucratides I

, the largest gold coin

ever minted in Antiquity.

Drachma of

Alexandria

, 222-235 AD. Obverse:

Laureate head of

Alexander Severus

, KAI(ΣΑΡ)

MAP(ΚΟΣ) AYP(ΗΛΙΟΣ) ΣЄY(ΑΣΤΟΣ) AΛЄΞANΔPOΣ ЄYΣЄ(ΒΗΣ). Reverse: Bust

of

Asclepius

.

The Hellenistic period was characterized by the spread of Greek

culture across a large part of the known world. Greek-speaking kingdoms were

established in Egypt

and

Syria

, and for a time also in

Iran and as far east as what is now

Afghanistan

and northwestern

India

. Greek traders spread Greek coins across

this vast area, and the new kingdoms soon began to produce their own coins.

Because these kingdoms were much larger and wealthier than the Greek city states

of the classical period, their coins tended to be more mass-produced, as well as

larger, and more frequently in gold. They often lacked the aesthetic delicacy of

coins of the earlier period.

Still, some of the

Greco-Bactrian

coins, and those of their

successors in India, the

Indo-Greeks

, are considered the finest examples

of

Greek numismatic art

with “a nice blend of

realism and idealization”, including the largest coins to be minted in the

Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by

Eucratides

(reigned 171–145 BC), the largest

silver coin by the Indo-Greek king

Amyntas Nikator

(reigned c. 95–90 BC). The

portraits “show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland

depictions of their royal contemporaries further West” (Roger Ling, “Greece and

the Hellenistic World”).

The most striking new feature of Hellenistic coins was the use of portraits

of living people, namely of the kings themselves. This practice had begun in

Sicily, but was disapproved of by other Greeks as showing

hubris

(arrogance). But the kings of

Ptolemaic Egypt

and

Seleucid Syria

had no such scruples: having

already awarded themselves with “divine” status, they issued magnificent gold

coins adorned with their own portraits, with the symbols of their state on the

reverse. The names of the kings were frequently inscribed on the coin as well.

This established a pattern for coins which has persisted ever since: a portrait

of the king, usually in profile and striking a heroic pose, on the obverse, with

his name beside him, and a coat of arms or other symbol of state on the reverse.

Minting

All Greek coins were

handmade

, rather than machined as modern coins

are. The design for the obverse was carved (in

incuso

) into a block of bronze or possibly

iron, called a

die

. The design of the reverse was carved into

a similar punch. A blank disk of gold, silver, or electrum was cast in a mold

and then, placed between these two and the punch struck hard with a hammer,

raising the design on both sides of the coin.

Coins as

a symbol of the city-state

Coins of Greek city-states depicted a unique

symbol

or feature, an early form of

emblem

, also known as

badge

in numismatics, that represented their

city and promoted the prestige of their state. Corinthian stater for example

depicted pegasus

the mythological winged stallion, tamed

by their hero

Bellerophon

. Coins of

Ephesus

depicted the

bee

sacred to

Artemis

. Drachmas of Athens depicted the

owl of Athena

. Drachmas of

Aegina

depicted a

chelone

. Coins of

Selinunte

depicted a “selinon” (σέλινον

– celery

). Coins of

Heraclea

depicted

Heracles

. Coins of

Gela depicted a man-headed bull, the personification of the river

Gela

. Coins of

Rhodes

depicted a “rhodon” (ῥόδον[8]

– rose

). Coins of

Knossos

depicted the

labyrinth

or the mythical creature

minotaur

, a symbol of the

Minoan Crete

. Coins of

Melos

depicted a “mēlon” (μήλον –

apple

). Coins of

Thebes

depicted a Boeotian shield.

Corinthian stater with

pegasus

Coin of

Rhodes

with a

rose

Didrachm of

Selinunte

with a

celery

Coin of

Ephesus

with a

bee

Stater of

Olympia

depicting

Nike

Coin of

Melos

with an

apple

Obolus from

Stymphalia

with a

Stymphalian bird

Coin of

Thebes

with a Boeotian shield

Coin of Gela

with a man-headed bull,

the personification of the river

Gela

Didrachm of

Knossos

depicting the

Minotaur

Commemorative coins

Dekadrachm

of

Syracuse

[disambiguation

needed]. Head of Arethusa or queen

Demarete. ΣΥΡΑΚΟΣΙΟΝ (of the Syracusians), around four dolphins

The use of

commemorative coins

to celebrate a victory or

an achievement of the state was a Greek invention. Coins are valuable, durable

and pass through many hands. In an age without newspapers or other mass media,

they were an ideal way of disseminating a political message. The first such coin

was a commemorative decadrachm issued by

Athens

following the Greek victory in the

Persian Wars

. On these coins that were struck

around 480 BC, the owl

of Athens, the goddess

Athena

‘s sacred bird, was depicted facing the

viewer with wings outstretched, holding a spray of olive leaves, the

olive tree

being Athena’s sacred plant and also

a symbol of peace and prosperity. The message was that Athens was powerful and

victorious, but also peace-loving. Another commemorative coin, a silver

dekadrachm known as ” Demareteion”, was minted at

Syracuse

at approximately the same time to

celebrate the defeat of the

Carthaginians

. On the obverse it bears a

portrait of

Arethusa

or queen Demarete.

Ancient Greek coins

today

Collections of Ancient Greek coins are held by museums around the world, of

which the collections of the

British Museum

, the

American Numismatic Society

, and the

Danish National Museum

are considered to be the

finest. The American Numismatic Society collection comprises some 100,000

ancient Greek coins from many regions and mints, from Spain and North Africa to

Afghanistan. To varying degrees, these coins are available for study by

academics and researchers.

There is also an active collector market for Greek coins. Several auction

houses in Europe and the United States specialize in ancient coins (including

Greek) and there is also a large on-line market for such coins.

Hoards of Greek coins are still being found in Europe, Middle East, and North

Africa, and some of the coins in these hoards find their way onto the market.

Coins are the only art form from the Ancient world which is common enough and

durable enough to be within the reach of ordinary collectors.

|