|

Greek King: Philip V – King of Macedonia: 221-179 B.C.

Bronze 20mm (8.40 grams) Struck circa 221-179 B.C.

Reference: SNGCop 1262

Head of bearded Hercules right in lion’s skin.

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ above and below harpa (flute), ΔI above, all within oak

wreath.

Son of Demetrios II, Philip V

came to power in 221 B.C. on the death of Antigonos Doson. He was a vigorous

ruler and maintained the power of the Macedonian kingdom in the earlier part of

his reign. However, he made the mistake of arousing the enmity of the Romans,

and in 197 B.C. his power was crushed at the battle of the Kynoskephalai by the

Roman general T. Quinctius Flamininus. After this his power and territory were

severely curtailed by Rome, and the days of the Macedonian kingdom were

numbered.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Hercules and the Hydra (ca.

1475) byAntonio

del Pollaiuolo the

hero wears his characteristic lionskin and wields a club

Hercules is the Roman name for

the Greek divine hero Heracles,

who was the son of Zeus (Roman

equivalent Jupiter)

and the mortal Alcmene.

In classical

mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous

far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Greek hero’s iconography and myths for their literature

and art under the name Hercules.

In later Western

art and literature and in popular

culture, Hercules is

more commonly used than Heracles as

the name of the hero. Hercules was a multifaceted figure with contradictory

characteristics, which enabled later artists and writers to pick and choose how

to represent him. This article

provides an introduction to representations of Hercules in the later

tradition.

Labours

Hercules capturing theErymanthian

Boar, by J.M.

Félix Magdalena (b.

1941)

Main article: Labours

of Hercules

Hercules is known for his many adventures, which took him to the far reaches of

the Greco-Roman

world. One cycle of these adventures became canonical as

the “Twelve Labours,” but the list has variations. One traditional order of the

labours is found in theBibliotheca as

follows:

- Slay the Nemean

Lion.

- Slay the nine-headed Lernaean

Hydra.

- Capture the Golden

Hind of Artemis.

- Capture the Erymanthian

Boar.

- Clean the Augean stables

in a single day.

- Slay the Stymphalian

Birds.

- Capture the Cretan

Bull.

- Steal the Mares

of Diomedes.

- Obtain the girdle of Hippolyta,

Queen of the Amazons.

- Obtain the cattle of the monster Geryon.

- Steal the apples of the Hesperides.

- Capture and bring back Cerberus.

Side adventures

Hercules had a greater number of “deeds

on the side” (parerga) that

have been popular subjects for art, including:

-

Killing a fire-breathingCacus (Sebald

Beham, 1545)

-

Holding up the world forAtlas (based

on Heinrich

Aldegrever, 1550)

-

Wrestling with Achelous(16th-century

plaque)

-

Fighting the giant Antaeus(Auguste

Couder, 1819)

-

Retrieving Alcestis from

the underworld (Paul

Cézanne, 1867)

-

Freeing Prometheus(Christian

Griepenkerl, 1878)

Roman era

Main article: Hercules

in ancient Rome

The Latin name Hercules was

borrowed through Etruscan,

where it is represented variously as Heracle,

Hercle, and other forms. Hercules was a favorite subject for Etruscan

art, and appears often on bronze

mirrors. The Etruscan form Herceler derives

from the Greek Heracles via syncope.

A mild oath invoking Hercules (Hercule! or Mehercle!)

was a common interjection in Classical

Latin.

Baby Hercules strangling asnake sent

to kill him in his cradle(Roman

marble, 2nd century CE)

Hercules had a number of myths that

were distinctly Roman. One of these is Hercules’ defeat of Cacus,

who was terrorizing the countryside of Rome. The hero was associated with the Aventine

Hill through his son Aventinus. Mark

Antony considered him a personal

patron god, as did the emperor Commodus.

Hercules received various forms of religious

veneration, including as a deity

concerned with children and childbirth, in part because of myths about his

precocious infancy, and in part because he fathered countless children. Roman

brides wore a special belt tied with the “knot

of Hercules”, which was supposed to be hard to untie. The

comic playwright Plautus presents

the myth of Hercules’ conception as a sex comedy in his play Amphitryon; Senecawrote

the tragedy Hercules Furens about

his bout with madness. During the Roman

Imperial era, Hercules was worshipped locally from Hispania through Gaul.

Germanic association

Tacitus records a special

affinity of the Germanic

peoples for Hercules. In chapter

3 of his Germania,

Tacitus states:

… they say that Hercules, too, once visited them; and when going into

battle, they sang of him first of all heroes. They have also those songs of

theirs, by the recital of this barditus as

they call it, they rouse their courage, while from the note they augur the

result of the approaching conflict. For, as their line shouts, they inspire

or feel alarm.

In the Roman era Hercules’

Club amulets appear from the 2nd

to 3rd century, distributed over the empire (including Roman

Britain, c.f. Cool 1986), mostly made of gold, shaped like wooden clubs. A

specimen found in Köln-Nippes bears

the inscription “DEO HER[culi]”,

confirming the association with Hercules.

In the 5th to 7th centuries, during the Migration

Period, the amulet is theorized to have rapidly spread from the Elbe

Germanic area across Europe.

These Germanic “Donar’s

Clubs” were made from deer antler, bone or wood, more rarely also from bronze or

precious metals.They are found exclusively in female graves, apparently worn

either as a belt pendant, or as an ear pendant. The amulet type is replaced by

the Viking

Age Thor’s

hammer pendants in the course of

the Christianization

of Scandinavia from the 8th to

9th century.

Medieval mythography

Hercules and the Nemean

lionin the 15th-century Histoires

de Troyes

After the Roman Empire became Christianized,

mythological narratives were often reinterpreted as allegory,

influenced by the philosophy of late

antiquity. In the 4th century, Servius had

described Hercules’ return from the underworld as representing his ability to

overcome earthly desires and vices, or the earth itself as a consumer of bodies. In

medieval mythography, Hercules was one of the heroes seen as a strong role model

who demonstrated both valor and wisdom, with the monsters he battles as moral

obstacles. One glossator noted

that when Hercules

became a constellation, he showed that strength was necessary to gain

entrance to Heaven.

Medieval mythography was written almost entirely in Latin, and original Greek

texts were little used as sources for Hercules’ myths.

Renaissance mythography

The Renaissance and

the invention of the printing

press brought a renewed interest

in and publication of Greek literature. Renaissance mythography drew more

extensively on the Greek tradition of Heracles, typically under the Romanized

name Hercules, or the alternate name Alcides.

In a chapter of his book Mythologiae (1567),

the influential mythographer Natale

Conti collected and summarized an

extensive range of myths concerning the birth, adventures, and death of the hero

under his Roman name Hercules. Conti begins his lengthy chapter on Hercules with

an overview description that continues the moralizing impulse of the Middle

Ages:

Hercules, who subdued and destroyed monsters, bandits, and criminals, was

justly famous and renowned for his great courage. His great and glorious

reputation was worldwide, and so firmly entrenched that he’ll always be

remembered. In fact the ancients honored him with his own temples, altars,

ceremonies, and priests. But it was his wisdom and great soul that earned

those honors; noble blood, physical strength, and political power just

aren’t good enough.

In art

In Roman works of art and in Renaissance and post-Renaissance art, Hercules can

be identified by his attributes, the lion

skin and the gnarled club (his

favorite weapon); in mosaic he

is shown tanned bronze, a virile aspect.

Roman era

-

Hercules of the Forum Boarium (Hellenistic,

2nd century BCE)

-

Hercules and Iolaus (1st

century CE mosaic from the Anzio Nymphaeum, Rome)

-

Hercules (Hatra,

Iraq,Parthian

period, 1st-2nd century CE)

-

Hercules bronze statuette, 2nd century CE (museum of Alanya, Turkey)

-

Hercules and the Nemean

Lion (detail), silver plate,

6th century (Cabinet

des Médailles, Paris)

Modern era

-

The Giant Hercules (1589)

by Hendrik

Goltzius

-

The Drunken Hercules(1612-1614) by Rubens

-

Hercules in the Augean

stable (1842, Honoré

Daumier)

-

Comic book cover

(c.1958)

-

Hercules, Deianira and

the Centaur Nessus, byBartholomäus

Spranger, 1580 – 1582

-

Henry IV of France, as Hercules vanquishing theLernaean

Hydra (i.e. theCatholic

League), byToussaint

Dubreuil, circa 1600. Louvre

Museum

In numismatics

Hercules was among the earliest figures on ancient Roman coinage, and has been

the main motif of many collector coins and medals since. One example is the 20

euro Baroque Silver coin issued

on September 11, 2002. The obverse side of the coin shows the Grand Staircase in

the town palace of Prince

Eugene of Savoy in Vienna,

currently the Austrian Ministry of Finance. Gods and demi-gods hold

its flights, while Hercules stands at the turn of the stairs.

-

Juno, with Hercules fighting a Centaur on

reverse (Roman, 215–15 BCE)

-

Club over his shoulder on a Roman denarius (ca.

100 BCE)

-

Maximinus II and

Hercules with club and lionskin (Roman, 313 CE)

-

Commemorative 5-francpiece

(1996), Hercules in center

Other cultural

references

-

Pillars of Hercules, representing the Strait

of Gibraltar (19th-century

conjecture of the Tabula

Peutingeriana)

-

The Cudgel of Hercules, a tall limestone rock

formation, with Pieskowa

Skała Castle in the

background

-

Hercules as heraldic

supporters in the royal

arms of Greece,

in use 1863–1973. The phrase “Ηρακλείς του στέμματος” (“Defenders of

the Crown”) has pejorative connotations (“chief henchmen”) in Greek.

In films

For a list of films featuring Hercules, see Hercules

in popular culture#Filmography.

A series of nineteen Italian Hercules movies were made in the late 1950s and

early 1960s. The actors who played Hercules in these films were Steve

Reeves, Gordon

Scott, Kirk Morris, Mickey

Hargitay, Mark Forest, Alan Steel, Dan

Vadis, Brad

Harris, Reg

Park, Peter

Lupus (billed as Rock

Stevens) and Michael Lane. A number of English-dubbed Italian films that

featured the name of Hercules in their title were not intended to be movies

about Hercules.

Philip V (Greek:

Φίλιππος Ε΄) (238 BC – 179 BC) was King of

Macedon

from 221 BC to 179 BC. Philip’s reign

was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of

Rome

. Philip was attractive and charismatic as

a young man. A dashing and courageous warrior, he was inevitably compared to

Alexander the Great

and was nicknamed the

darling of Hellas (Greek:

η αγάπη μου για Ελλάδα).

//

Early

life

The son of

Demetrius II

and Chryseis, Philip was nine

years old at his father’s death in 229 BC. He had an elder paternal half sister

called Apame

. His cousin,

Antigonus Doson

, administered the kingdom as

regent until his death in 221 BC when Philip was seventeen years old.

On his ascent to the throne, Philip quickly showed that while he was young,

this did not mean that Macedon was weak. In the first year of his rule, he

pushed back the Dardani

and other tribes in the north of the

country.

The

Social War

In the Social War (220

BC–217

BC), the Hellenic League of Greek states was assembled at Philip V’s

instigation in Corinth

. He then led the Hellenic League in

battles against Aetolia

,

Sparta

and

Elis. At the same time he was able to stamp on his own authority

amongst his own ministers. His leadership during the Social War made him

well-known and respected both within his own kingdom and abroad.

First

Macedonian War

After the Peace of Naupactus in 217 BC, Philip V tried to replace

Roman

influence along the eastern shore of the

Adriatic

, forming alliances or lending

patronage to certain island and coastal provinces such as

Lato on Crete. He first tried to invade

Illyria

from the sea, but with limited success.

His first expedition in 216 BC had to be aborted, while he suffered the loss of

his whole fleet in a second expedition in 214 BC. A later expedition by land met

with greater success when he captured

Lissus

in 212 BC.

In 215 BC he entered into a treaty with

Hannibal

, the

Carthaginian

general then in the middle of an

invasion of Roman Italy. Their treaty defined spheres of operation and interest,

but achieve little of substance or value for either side. Philip became heavily

involved in assisting and protecting his allies from attacks from the

Spartans

, the Romans and their allies.

Rome’s alliance with the

Aetolian League

in 211 BC effectively

neutralised Philip’s advantage on land. The intervention of

Attalus I of Pergamum

on the Roman side further

exposed Philip’s position in Macedonia.

Philip was able to take advantage of the withdrawal of Attalus from the Greek

mainland in 207 BC, along with Roman inactivity and the increasing role of

Philopoemen

, the

strategos

of the

Achaean League

. After sacking Thermum, the

religious and political centre of

Aetolia

, Philip was able to force the Aetolians

to accept his terms in 206 BC. The following year he was able to conclude the

Peace of Phoenice

with Rome and its allies.

Expansion

in the Aegean

Following an agreement with the

Seleucid

king

Antiochus III

to capture Egyptian held

territory from the boy king

Ptolemy V

, Philip was able to gain control of

Egyptian territory in the

Aegean Sea

and in

Anatolia

. This expansion of Macedonian

influence created alarm in a number of neighbouring states, including

Pergamum

and

Rhodes

. Their navies clashed with Philip’s off

Chios

and

Lade (near

Miletus

) in 201 BC. At around the same time,

the Romans were finally the victorious over Carthage.

Second

Macedonian War

Kingdom of Macedon on the eve of the Second Macedonian War, circa

200 BC.

In 200 BC, with Carthage no longer a threat, the Romans declared war on

Macedon arguing that they were intervening to protect the freedom of the Greeks.

After campaigns in

Macedonia

in 199 BC and

Thessaly

in 198 BC, Philip and his Macedonian

forces were decisively defeated at the

Battle of Cynoscephalae

in 197 BC. The war also

proved the superiority of the

Roman legion

over the Greek

phalanx formation

.

Alliance

with Rome

The resulting peace treaty between Philip V and the Romans confined Philip to

Macedonia and required him to pay 1000

talents

indemnity

, surrender most of its fleet and

provide a number of hostages, including his younger son Demetrius. After this,

Philip cooperated with the Romans and sent help to them in their fight against

the Spartans under King

Nabis

in 195 BC. Philip also supported the

Romans against Antiochus III (192 BC-189 BC).

In return for his help when Roman forces under

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus

and his

brother

Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus

moved through

Macedon and Thrace

in 190 BC, the Romans forgave the

remaining indemnity that he had to pay and his son Demetrius was freed. Philip

then focused on consolidating power within Macedon. He reorganised the country’s

internal affairs and finances, mines were reopened and a new currency was

issued.

Final

years

However, Rome continued to be suspicious of Philip’s intentions. Accusations

by Macedon’s neighboring states, particularly

Pergamum

, led to constant interference from

Rome. Feeling the threat growing that Rome would invade Macedon and remove him

as king, he tried to extend his influence in the

Balkans

by force and diplomacy. However, his

efforts were undermined by the pro-Roman policy of his younger son Demetrius,

who was encouraged by Rome to consider the possibility of succession ahead of

his older brother,

Perseus

. This eventually led to a quarrel

between Perseus and Demetrius which forced Philip to reluctantly decide to

execute Demetrius for treason in 180 BC. This decision had a severe impact on

Philip’s health and he died a year later at

Amphipolis

.

He was succeeded by his eldest son

Perseus

, who ruled as the last king of

Macedon

.

Macedonia or Macedon (from

Greek

: Μακεδονία,

Makedonía) was an

ancient kingdom

, centered in the northeastern part of

the

Greek peninsula

,

bordered by

Epirus

to the west,

Paionia

to the north, the region of

Thrace

to the east and

Thessaly

to the south. For a brief period,

after the conquests of

Alexander the Great

, it became the most

powerful state in the world, controlling a territory that included most of

Greece

and

Persia

, stretching as far as the

Indus River

; at that time it inaugurated the

Hellenistic period

of

history

.

Name

The name Macedonia (Greek:

Μακεδονία,

Makedonía) is related to

the ancient Greek word μακεδνός (Makednos).

It is commonly explained as having originally meant ‘a tall one’ or

‘highlander’, possibly descriptive of the

people

. The shorter English name variant

Macedon developed in Middle English, based on a borrowing from the French

form of the name, Macédoine.

History

Early history and

legend

The lands around Aegae, the first Macedonian capital, were home to various

peoples. Macedonia was called Emathia (from king Emathion) and the city of Aiges

was called Edessa, the capital of fabled king Midas. According to legend,

Caranus, accompanied by a multitude of Greeks came to the area in search for a

new homeland

[5]

took Edessa and renamed it to Aegae.

Subsequently, he expelled Midas and other kings off the lands and he formed his

new kingdom. According to Herodot, it was Dorus, the son of Hellen who led his

people to Histaeotis, whence they were driven off by the Cadmeians into Pindus,

where they settled as Macedonians. Later, a branch would migrate further south

to be called Dorians

[6]

.

It seems that the first

Macedonian

state emerged in the

8th

or early

7th century BC

under the

Argead Dynasty

, who, according to legend,

migrated to the region from the

Greek city

of

Argos

in Peloponnesus (thus the name Argead).[7]

It should be mentioned that the Macedonian tribe ruled by the Argeads, was

itself called Argead (which translates as “descended from Argos”).

The kingdom was situated in the fertile alluvial plain, watered by the rivers

Haliacmon

and

Axius

, called Lower Macedonia, north of

the mountain

Olympus

. Around the time of

Alexander I of Macedon

, the Argead Macedonians

started to expand into

Upper Macedonia

, lands inhabited by independent

Macedonian tribes like the Lyncestae and the Elmiotae and to the West, beyond

Axius river, into

Eordaia

,

Bottiaea

,

Mygdonia

, and

Almopia

-, regions settled by, among others,

many Thracian tribes.[8]

Near the modern city of

Veria

,

Perdiccas I

(or, more likely, his son,

Argaeus I

) built his capital, Aigai (modern

Vergina

). After a brief period under

Persian

rule under

Darius Hystaspes

, the state regained its

independence under King

Alexander II

(495–450

BC).

Macedon during the

Peloponnesian Warr

around 431 BC.

In the long

Peloponnesian War

Macedon was a secondary power

that alternated in support between Sparta and Athens.

Involvement in

the Greek world

Prior to the

4th century BC

, the kingdom covered a region

approximately corresponding to the

province of Macedonia

of modern

Greece Amyntas III

(c.

393

–370

BC), though it still retained strong contrasts between the

cattle-rich coastal plain and the fierce isolated tribal hinterland, allied to

the king by marriage ties. They controlled the passes through which barbarian

invasions came from

Illyria

to the north and northwest. It became

increasingly

Atticised

during this period, though prominent

Athenians

appear to have regarded the

Macedonians as uncouth.[10]

Before the establishment of the

League of Corinth

, even though the Macedonians

apparently spoke a dialect of the Greek language and claimed proudly that they

were Greeks, they were not considered to fully share the

classical Greek

culture by many of the

inhabitants of the southern city states, because they did not share the

polis

based style of government of the

southerners.[9]

Herodotus

, being one of the foremost biographer

in antiquity who lived in Greece at the time when the Macedonian king

Alexander I

was in power, mentioned: “I

happen to know, and I will demonstrate in a subsequent chapter of this history,

that these descendants of Perdiccas are, as they themselves claim, of Greek

nationality. This was, moreover, recognized by the managers of the

Olympic games

, on the occasion when

Alexander

wished to compete and his Greek

competitors tried to exclude him on the ground that foreigners were not allowed

to take part. Alexander, however, proved his Argive descent, and so was accepted

as a Greek and allowed to enter for the foot-race. He came in equal first”..[11]

Over the 4th century Macedon became more politically involved with the

south-central city-states of

Ancient GreecePella

, resembling

Mycenaean

culture more than classic

Hellenic

city-states, and other archaic

customs, like Philip’s multiple wives in addition to his Epirote queen

Olympias

, mother of Alexander.

Another archaic remnant was the very persistence of a

hereditary

monarchy

which wielded formidable – sometimes

absolute – power, although this was at times checked by the landed aristocracy,

and often disturbed by power struggles within the royal family itself. This

contrasted sharply with the Greek cultures further south, where the ubiquitous

city-states mostly possessed aristocratic or democratic institutions; the

de facto

monarchy of

tyrants

, in which heredity was usually more of

an ambition rather than the accepted rule; and the limited, predominantly

military and sacerdotal, power of the twin hereditary

Spartan

kings. The same might have held true of

feudal

institutions like

serfdom

, which may have persisted in Macedon

well into historical times. Such institutions were abolished by city-states well

before Macedon’s rise (most notably by the Athenian legislator

Solon

‘s famous

σεισάχθεια

seisachtheia

laws)..

Amyntas had three sons; the first two,

Alexander II

and

Perdiccas III

reigned only briefly. Perdiccas

III’s infant heir was deposed by Amyntas’ third son,

Philip II of Macedon

, who made himself king and

ushered in a period of Macedonian dominance of Greece. Under Philip II, (359–336

BC), Macedon expanded into the territory of the

Paionians

,

Thracians

, and

Illyrians

. Among other conquests, he annexed

the regions of

Pelagonia

and Southern

Paionia

.[12]]

Kingdom of Macedon after Philip’s II death.

Philip redesigned the

army of Macedon

adding a number of variations

to the traditional

hoplite

hetairoi

, a well armoured heavy cavalry, and

more light infantry, both of which added greater flexibility and responsiveness

to the force. He also lengthened the spear and shrank the shield of the main

infantry force, increasing its offensive capabilities.

Philip began to rapidly expand the borders of his kingdom. He first

campaigned in the north against non-Greek peoples such as the

IllyriansAmphipolis

, which controlled the way

into Thracee

and also was near valuable silver

mines. This region had been part of the

Athenian Empire

, and Athens still considered it

as in their sphere. The Athenians attempted to curb the growing power of

Macedonia, but were limited by the outbreak of the

Social War

. They could also do little to halt

Philip when he turned his armies south and took over most of

Thessaly

.

Control of Thessaly meant Philip was now closely involved in the politics of

central Greece. 356 BCE saw the outbreak of the

Third Sacred War

that pitted

Phocis

against

Thebes

and its allies. Thebes recruited the

Macedonians to join them and at the

Battle of Crocus Field

Phillip decisively

defeated Phocis and its Athenian allies. As a result Macedonia became the

leading state in the

Amphictyonic League

and Phillip became head of

the Pythian Games, firmly putting the Macedonian leader at the centre of the

Greek political world.

In the continuing conflict with Athens Philip marched east through Thrace in

an attempt to capture

Byzantium

and the

Bosphorus

, thus cutting off the Black Sea grain

supply that provided Athens with much of its food. The siege of Byzantium

failed, but Athens realized the grave danger the rise of Macedon presented and

under Demosthenes

built a coalition of many of the

major states to oppose the Macedonians. Most importantly Thebes, which had the

strongest ground force of any of the city states, joined the effort. The allies

met the Macedonians at the

Battle of Chaeronea

and were decisively

defeated, leaving Philip and the Macedonians the unquestioned master of Greece.

Empire

Alexander’s empire at the time of its maximum expansion

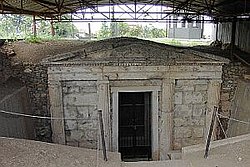

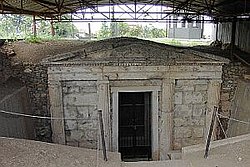

The entrance to one of the royal tombs at Vergina, a UNESCO World

Heritage site.

Philip’s son,

Alexander the Great

(356–323

BC), managed to briefly extend Macedonian power not only over the

central Greek city-states, but also to the

Persian empire

, including

Egypt

and lands as far east as the fringes of

India

. Alexander’s adoption of the styles of

government of the conquered territories was accompanied by the spread of Greek

culture and learning through his vast empire. Although the empire fractured into

multiple Hellenic regimes shortly after his death, his conquests left a lasting

legacy, not least in the new Greek-speaking cities founded across Persia’s

western territories, heralding the

Hellenistic

Diadochi, Macedonia fell to the

Antipatrid dynasty

, which was overthrown by the

Antigonid dynasty

after only a few years, in

294 BC..

Hellenistic era

Antipater

and his son

Cassander

gained control of Macedonia but it

slid into a long period of civil strife following Cassander’s death in

297 BC

. It was ruled for a while by

Demetrius I

(294–288

BC) but fell into civil war.

Demetrius’ son,

Antigonus II

(277–239

BC), defeated a

Galatian

invasion as a

condottiere

, and regained his family’s

position in Macedonia; he successfully restored order and prosperity there,

though he lost control of many of the Greek city-states. He established a stable

monarchy under the

Antigonid dynasty

.

Antigonus III

((239–221

BC) built on these gains by re-establishing Macedonian power across

the region.

What is notable about the Macedonian regime during the Hellenistic times is

that it was the only successor state to the Empire that maintained the old

archaic perception of Kingship, and never adopted the ways of the Hellenistic

Monarchy. Thus the king was never deified in the same way that Ptolemies and

Seleucids were in Egypt and Asia respectively, and never adopted the custom of

Proskynesis

. The ancient Macedonians during the

Hellenistic times were still addressing their kings in a far more casual way

than the subjects of the rest of the Diadochi, and the Kings were still

consulting with their aristocracy (Philoi) in the process of making their

decisions.

Conflict with Rome

Kingdom of Macedon under Philip V.

Under

Philip V of Macedon

(221–179

BC Perseus of Macedon (179–168

BC), the kingdom clashed with the rising power of the

Roman Republic

. During the

2nd

and

1st centuries BC

, Macedon fought a

series of wars

with Rome. Two major losses that

led to their inevitable defeat were in

197 BC

when Rome defeated Philip V, and

168 BC

when Rome defeated Perseus. The overall

losses resulted in the defeat of Macedon, the deposition of the Antigonid

dynasty and the dismantling of the Macedonian kingdom.

Andriscus

‘ brief success at reestablishing the

monarchy in 149 BCC

was quickly followed by his defeat the

following year and the establishment of direct

Roman

rule and the organization of Macedon as

the

Roman province of Macedonia

.

Institutions

éthnē), and between the two, the districts. The study of these different

institutions has been considerably renewed thanks to

epigraphy

, which has given us the possibility

to reread the indications given us by ancient literary sources such as

Livy and

Polybius

. They show that the Macedonian

institutions were near to those of the Greek federal states, like the

Aetolian

and

Achaeann

leagues, whose unity was reinforced by

the presence of the king.

The

Vergina Sun

, the 16-ray star covering

what appears to be the royal burial larnax of Philip II of Macedon,

discovered in Vergina, Greece.

The King

The king

Βασιλεύς,

Basileús) headed the

central administration: he led the kingdom from its capital, Pella, and in his

royal palace was conserved the state’s archive. He was helped in carrying out

his work by the Royal Secretary (βασιλικὸς

γραμματεύς, basilikós

grammateús), whose work was of primary importance, and by the

Council

.

The king was commander of the army, head of the Macedonian religion, and

director of diplomacy. Also, only he could conclude treaties, and, until

Philip V

, mint coins.

The number of civil servants was limited: the king directed his kingdom

mostly in an indirect way, supporting himself principally through the local

magistrates, the epistates, with whom he constantly kept in touch.

Successionon

Royal succession in Macedon was hereditary, male,

patrilineal

and generally respected the

principle of

primogeniture

. There was also an elective

element: when the king died, his designated heir, generally but not always the

eldest son, had first to be accepted by the council and then presented to the

general Assembly to be acclaimed king and obtain the oath of fidelity.

Perdiccas III, slain by the

Illyrians

,

Philip II

assassinated by

Pausanias of Orestis

,

Alexander the Great

, suddenly died of malady,

etc. Succession crises were frequent, especially up to the

4th century BC

, when the magnate families of

Upper Macedonia still cultivated the ambition of overthrowing the Argaead

dynasty and to ascend to the throne.

An atrium with a pebble-mosaic paving, in Pella, Greece

Financesces

The king was the simple guardian and administrator of the treasure of Macedon

and of the king’s incomes (βασιλικά,

basiliká), which belonged

to the Macedonians: and the tributes that came to the kingdom thanks to the

treaties with the defeated people also went to the Macedonian people, and not to

the king. Even if the king was not accountable for his management of the

kingdom’s entries, he may have felt responsible to defend his administration on

certain occasions: Arrian

tells us that during the

mutiny

of Alexander’s soldiers at

Opis in 324 BC BC

, Alexander detailed the possessions

of his father at his death to prove he had not abused his charge.

It is known from Livy and Polybius that the basiliká included the

following sources of income:

- The mines of gold and silver (for example those of the

Pangaeus

), which were the exclusive

possession of the king, and which permitted him to strike currency, as

already said his sole privilege till Philip V, who conceded to cities and

districts the right of coinage for the lesser denominations, like bronze.

- The forests, whose timber was very appreciated by the Greek

cities to build their ships: in particular, it is known that

Athens

made commercial treaties with

Macedon in the

5th century BC

to import the timber

necessary for the construction and the maintenance of its fleet of war.

- The royal landed properties, lands that were annexed to the royal

domain through conquest, and that the king exploited either directly, in

particular through servile workforce made up of prisoners of war, or

indirectly through a leasing system.

- The port duties on commerce (importation and exportation taxes).

The most common way to exploit these different sources of income was by

leasing: the Pseudo-Aristotle

reports in the

Oeconomica

that

Amyntas III

(or maybe Philip II) doubled the

kingdom’s port revenues with the help of

Callistratus

, who had taken refuge in Macedon,

bringing them from 20 to 40

talents

per year. To do this, the exploitation

of the harbour taxes was given every year at the private offering the highest

bidding. It is also known from Livy that the mines and the forests were leased

for a fixed sum under Philip V, and it appears that the same happened under the

Argaead dynasty: from here possibly comes the leasing system that was used in

Ptolemaic Egypt

.

Except for the king’s properties, land in Macedon was free: Macedonians were

free men and did not pay land taxes on private grounds. Even extraordinary taxes

like those paid by the Athenians in times of war did not exist. Even in

conditions of economic peril, like what happened to Alexander in

334 BC< and Perseus in

168 BC

, the monarchy did not tax its subjects

but raised funds through loans, first of all by his Companions, or raised the

cost of the leases.

The king could grant the atelíē (ἀτελίη),

a privilege of tax exemption, as Alexander did with those Macedonian families

which had losses in the

battle of the Granicus

in May

334334

: they were exempted from paying tribute

for leasing royal grounds and commercial taxes.

Extraordinary incomes came from the spoils of war, which were divided between

the king and his men. At the time of Philip II and Alexander, this was a

considerable source of income. A considerable part of the gold and silver

objects taken at the time of the European and Asian campaigns were melted in

ingots and then sent to the monetary foundries of

Pella

Amphipolis, most active of the kingdom at

that time: an estimate judges that during the reign of Alexander only the mint

of Amphipolis struck about 13 million silver

tetradrachms

.

The Assembly

All the kingdom’s citizen-soldiers gather in a popular assembly, which is

held at least twice a year, in spring and in autumn, with the opening and the

closing of the campaigning season.

This assembly (koinê ekklesia

or koinon makedonôn), of

the army in times of war, of the people in times of peace, is called by the king

and plays a significant role through the acclamation of the kings and in capital

trials; it can be consulted (without obligation) for the foreign politics

(declarations of war, treaties) and for the appointment of high state officials.

In the majority of these occasions, the Assembly does nothing but ratify the

proposals of a smaller body, the Council. It is also the Assembly which votes

the honors, sends embassies, during its two annual meetings. It was abolished by

the Romans

at the time of their reorganization of

Macedonia in 167 BC

, to prevent, according to

Livy, that a demagogue could make use of it as a mean to revolt

against their authority.

The Friends (philoi)

or the king’s Companions (basilikoi

hetairoi

) were named for life by the king

among the Macedonian aristocracy.cy.

The most important generals of the army (hégémones

tôn taxéôn), also named by the king.

The king had in reality less power in the choice of the members of the

Council than appearances would warrant; this was because many of the kingdom’s

most important noblemen were members of the Council by birth-right.

The Council primarily exerted a probouleutic function with respect to the

Assembly: it prepared and proposed the decisions which the Assembly would have

discussed and voted, working in many fields such as the designation of kings and

regents, as of that of the high administrators and the declarations of war. It

was also the first and final authority for all the cases which did not involve

capital punishment.

The Council gathered frequently and represented the principal body of

government of the kingdom. Any important decision taken by the king was

subjected before it for deliberation.on.

Inside the Council ruled the democratic principles of iségoria

(equality of word) and of parrhésia (freedom of speech), to which even

the king subjected himself.

After the removal of the

Antigonid dynasty

by the Romans in

167 BC

, it is possible that the synedrion

remained, unlike the Assembly, representing the sole federal authority in

Macedonia after the country’s division in four merides.

Regional

districts (Merides)

The creation of an intermediate territorial administrative level between the

central government and the cities should probably be attributed to Philip II:

this reform corresponded with the need to adapt the kingdom’s institutions to

the great expansion of Macedon under his rule. It was no longer practical to

convene all the Macedonians in a single general assembly, and the answer to this

problem was the creation of four regional districts, each with a regional

assembly. These territorial divisions clearly did not follow any historical or

traditional internal divisions; they were simply artificial administrative

lines.

This said, it should be noted that the existence of

these districts is not attested with certainty (by

numismatics

) before the beginning of the

2nd century BC

.

|