|

Jewish Coin of

Salome Alexandra – Shlomozion (Queen of Israel: 76-67 BC)

Regent for John Hyrcanus II (67 and 63-40 BC) or Aristobulus II (67-63 BC)

Bronze ‘Prutah’ 14mm (2.11 grams) Jerusalem mint, struck circa 76-40 B.C.

Reference: Hendin 1159 (5th Edition); Hendin 6186 (6th Edition)

Paleo-Hebrew inscription (Yehohanan the High Priest …) within wreath.

Double cornucopia adorned with ribbons, pomegranate between horns.

Coin Notes:

This coin is a recent discovery. Possibly a coincidental overstrike of 1149, due to abbreviated spelling of the King’s name as on 1149. Queen Salome Alexandra could have minted coins on behalf of her son Hyrcanus II the high priest and it is possible they continued being struck afterwards for years, even under Aristobolus II.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

Starting with the Jewish Kings, most coins were minted at the Jerusalem mint. The Hosmoneon Dynasty coinage begins with John Hyrcanus I (135-104 B.C.) followed by Judah Aristobulus (104 B.C.), then Alexander Jannaeus (104-76 B.C.). The Herodian Dynasty came next with Herod I (the Great) (40-4 B.C.), followed by Herod Archelaus (4 B.C. – 6 A.D.), Herod Antipas (4 B.C. – 39 A.D.), Herod Philip and Herod Agrippa I (41-44 A.D.).

Roman Procurator coinage was issued under procurators and prefects of the province of Judaea which minted coins with names of contemporary emperors between circa 6 – 66 A.D. They minted only one denomination and size, the bronze Prutah. Not all of the procurators and prefects issued coinage in the province of Judaea under the Romans. Those that did issue coins were Coponius (6-9 A.D.) (under the Roman emperor Augustus, 27 B.C.-14A.D.), Marcus Ambibulus (9-12 A.D.), Valerius Gratus (15-18/26 A.D.) (time of Roman emperor Tiberius 14-37 A.D.), Pontius Pilate (26-36 A.D.), Antonius Felix (52-60 A.D.) (under Roman emperor Claudius 41-54 A.D.), and Porcius Festus (59-62 A.D.) (under emperor Nero 54-68 A.D.). The last three procurators were Lucceius Albinus, Gessius Florus and Marcus Antonius Julianus. They did not issue any coins since the First Jewish-Roman War was brewing during emperor Nero’s reign and the leaders of the revolt started issuing their own coins for the period known as the Jewish War (67-70 A.D.).

After the conquest of Jerusalem under Vespasian and Titus, this period of coinage ended and Romans commemorated the victories over Jerusalem and the surrounding area with Judaea Capta coinage.

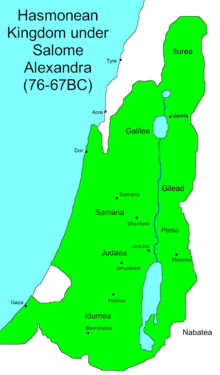

Salome Alexandra, or Shlomtzion (Greek: Σαλώμη Ἀλεξάνδρα; Hebrew: שְׁלוֹמְצִיּוֹן, Šəlōmṣīyyōn; 141–67 BCE), was one of only two women to rule over Judea (the other being Athaliah). The wife of Aristobulus I, and afterward of Alexander Jannaeus, she was the last regnant queen of Judea, and the last ruler of Judea to die as the sovereign of an independent kingdom.

Salome Alexandra’s personal genealogy is not given by Josephus, nor does it appear in any of the books of Maccabees. Rabbinical sources designate the rabbi, Simeon ben Shetah, as her brother, making her the daughter of Shetah as well. Salome Alexandra’s oldest son by Alexander Jannaeus was Hyrcanus II who fought his younger brother Aristobulus II in 73 BCE over the Jewish High Priesthood. Hyrcanus II was eventually successful after enlisting the help of the Nabataean king, Aretas III; bribing Roman officials, including Scaurus; and gaining the favour of Pompey the Great, who defeated his brother and took him away to Rome. Salome Alexandra’s personal genealogy is not given by Josephus, nor does it appear in any of the books of Maccabees. Rabbinical sources designate the rabbi, Simeon ben Shetah, as her brother, making her the daughter of Shetah as well. Salome Alexandra’s oldest son by Alexander Jannaeus was Hyrcanus II who fought his younger brother Aristobulus II in 73 BCE over the Jewish High Priesthood. Hyrcanus II was eventually successful after enlisting the help of the Nabataean king, Aretas III; bribing Roman officials, including Scaurus; and gaining the favour of Pompey the Great, who defeated his brother and took him away to Rome.

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, Salome Alexandra was instrumental in arranging the assassination of her brother-in-law, Antigonus, by convincing her husband that his brother was plotting against him. Upon the death of Aristobulus in 103 BCE, Aristobulus’ widow freed his half-brother, Alexander Jannaeus, who had been held in prison.

During the reign of Alexander, who (according to the historian Josephus) apparently married her shortly after his accession, Alexandra seemed to have wielded only slight political influence, as evidenced by the hostile attitude of the king to the Pharisees.

The frequent visits to the palace of the chief of the Pharisaic party, Simeon ben Shetach, who was said to be the queen’s brother, must have occurred in the early years of Alexander’s reign, before Alexander had openly broken with the Pharisees. Alexandra does not seem to have been able to prevent the persecution of that sect by her husband.

According to archaeologist Kenneth Atkinson, “There are also some passages in the Talmud that say, during her husband’s reign, that she protected Pharisees and hid Pharisees from his wrath.” Nevertheless, the married life of the royal pair seems to have ended cordially; on his deathbed Alexander entrusted the government, not to his sons, but to his wife, with the advice to make peace with the Pharisees.

Salome Alexandra’s next concern was to open negotiations with the leaders of the Pharisees, whose places of concealment she knew. Having been given assurances as to her future policy, they declared themselves ready to give Alexander’s remains the obsequies due to a monarch. By this step she avoided any public affront to the dead king, which, owing to the embitterment of the people, would certainly have found expression at the interment. This might have been attended with dangerous results for the Hasmonean dynasty.

Salome Alexandra received the reins of government (76 or 75 BCE) at Jannaeus’ camp before Ragaba, and concealed the king’s death until the fortress had fallen, in order that the rigour of the siege might be maintained. She succeeded for a time in quietening the vexatious internal dissensions of the kingdom that existed at the time of Alexander’s death; and she did this peacefully and without detriment to the political relations of the Jewish state to the outside world. Alexandra managed to secure assent to a Hasmonean monarchy from the Pharisees, who had suffered under Alexander.

The Pharisees now became not only a tolerated section of the community, but actually the ruling class. Salome Alexandra installed as high priest her eldest son, Hyrcanus II, a man who was wholly supportive of the Pharisees and the Sanhedrin was reorganized according to their wishes and became a supreme court for the administration of justice and religious matters, the guidance of which was placed in the hands of the Pharisees.

The Sadducees were moved to petition the queen for protection against the ruling party. Salome Alexandra, who desired to avoid all party conflict, removed the Sadducees from Jerusalem, assigning certain fortified towns for their residence.

Salome Alexandra increased the size of the army and carefully provisioned the numerous fortified places so that neighbouring monarchs were duly impressed by the number of protected towns and castles which bordered the Judean frontier. As well, she did not abstain from actual warfare; she sent her son Aristobulus with an army to besiege Damascus, then beleaguered by Ptolemy Menneus. The expedition reportedly achieved little.

The last days of Salome Alexandra’s reign were tumultuous. Her son, Aristobulus, endeavoured to seize the government, and succeeded her after her death.

Rabbinical sources refer in glowing terms to the prosperity which Judea enjoyed under Salome Alexandra. The Haggadah (Ta’anit, 23a; Sifra, ḤuḲḲat, i. 110) relates that during her rule, as a reward for her piety, rain fell only on Sabbath (Friday) nights; so that the working class suffered no loss of pay through the rain falling during their work-time. The fertility of the soil was so great that the grains of wheat grew as large as kidney beans; oats as large as olives; and lentils as large as gold denarii. The sages collected specimens of these grains and preserved them to show future generations the rewards of obedience to the Law, and what piety could achieve.

“Shlomtzion” (Hebrew: שלומציון), derived from the queen’s name, is sometimes used as a female first name in contemporary Israel. Among others, the well-known Israeli writer Amos Kenan bestowed that name on his daughter.

During the British Mandate of Palestine, a major street in Jerusalem was called ” Princess Mary Street”. After the creation of Israel, this name of a British Royal was changed to “Queen Shlomzion Street”, to commemorate the Jewish Queen. Such street names exist also in Tel Aviv and Ramat Gan.

In the 1977 Knesset elections Ariel Sharon accepted the advice of Kenan to give the name “Shlomtzion” to a new political party which Sharon was forming at the time (it later merged with the Likud).

Israeli zoologists carefully observing the Leopards of the Judean Desert have bestowed the name “Shlomtzion” on a female whose life, mating and offspring were the subject of intensive, years-long study.

Prutah (Hebrew: פרוטה) is a word borrowed from the Mishnah and the Talmud, in which it means “a coin of smaller value”. The word was probably derived originally from an Aramaic word with the same meaning.

The prutah was an ancient copper Jewish coin with low value. A loaf of bread in ancient times was worth about 10 prutot (plural of prutah). One prutah was also worth two lepta (singular lepton), which was the smallest denomination minted by the Hasmonean and Herodian Dynasty kings.

Prutot were also minted by the Roman Procurators of the Province of Judea, and later were minted by the Jews during the First Jewish Revolt (sometimes called ‘Masada coins’).

The Lesson of the widow’s mite is presented in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 12:41-44, Luke 21:1-4), in which Jesus is teaching at the Temple in Jerusalem. The Gospel of Mark specifies that two mites (Greek lepta) are together worth a quadrans, the smallest Roman coin. A lepton was the smallest and least valuable coin in circulation in Judea, worth about six minutes of an average daily wage.

In the story, a widow donates two small coins, while wealthy people donate much more. Jesus explains to his disciples that the small sacrifices of the poor mean more to God than the extravagant, but proportionately lesser, donations of the rich.

“He sat down opposite the treasury and observed how the crowd put money into the treasury. Many rich people put in large sums. A poor widow also came and put in two small coins worth a few cents. Calling his disciples to himself, he said to them, ‘Amen, I say to you, this poor widow put in more than all the other contributors to the treasury. For they have all contributed from their surplus wealth, but she, from her poverty, has contributed all she had, her whole livelihood.’

|

Salome Alexandra’s personal genealogy is not given by Josephus, nor does it appear in any of the books of Maccabees. Rabbinical sources designate the rabbi, Simeon ben Shetah, as her brother, making her the daughter of Shetah as well. Salome Alexandra’s oldest son by Alexander Jannaeus was Hyrcanus II who fought his younger brother Aristobulus II in 73 BCE over the Jewish High Priesthood. Hyrcanus II was eventually successful after enlisting the help of the Nabataean king, Aretas III; bribing Roman officials, including Scaurus; and gaining the favour of Pompey the Great, who defeated his brother and took him away to Rome.

Salome Alexandra’s personal genealogy is not given by Josephus, nor does it appear in any of the books of Maccabees. Rabbinical sources designate the rabbi, Simeon ben Shetah, as her brother, making her the daughter of Shetah as well. Salome Alexandra’s oldest son by Alexander Jannaeus was Hyrcanus II who fought his younger brother Aristobulus II in 73 BCE over the Jewish High Priesthood. Hyrcanus II was eventually successful after enlisting the help of the Nabataean king, Aretas III; bribing Roman officials, including Scaurus; and gaining the favour of Pompey the Great, who defeated his brother and took him away to Rome.