|

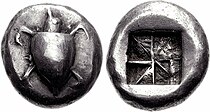

Greek City of Sardes in Asia Minor

Bronze 15mm (4.13 grams) Struck 133-80 B.C.

Reference: Sear 4736; B.M.C. 22.239,18

Laureate head of Apollo right.

ΣΑΡΔΙ /ΑΝΩΝ either side of club, monogram to right; all within oak-wreath.

The ancient capital of the Lydian Kings, Sardeis lay under a

fortified hill in the Hermos valley, at the important road junction. In the

pre-Alexandrian age it was the center of the principal Persian satrapy, ad in

all probability the mint-place of much of the Persian imperial coinage of darics

and sigloi. In 189 B.C. it came under the rule of the Attalids of Pergamon, and

fifty-six years later it passes to the Romans.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Apollo Belvedere

,

ca. 120–140 CE

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the

Olympian deities

in

ancient Greek

and

Roman religion

,

Greek

and

Roman mythology

, and

Greco

–Roman

Neopaganism

. The ideal of the

kouros

(a beardless, athletic youth),

Apollo has been variously recognized as a god of light and the sun, truth and

prophecy, healing, plague, music, poetry, and more. Apollo is the son of

Zeus and Leto

, and has a twin sister, the chaste

huntress Artemis

. Apollo is known in Greek-influenced

Etruscan mythology

as Apulu.

As the patron of Delphi

(Pythian Apollo), Apollo was an

oracular

god—the prophetic deity of the

Delphic Oracle

. Medicine and healing are

associated with Apollo, whether through the god himself or mediated through his

son Asclepius

, yet Apollo was also seen as a god

who could bring ill-health and deadly

plague

. Amongst the god’s custodial charges,

Apollo became associated with dominion over

colonists

, and as the patron defender of herds

and flocks. As the leader of the

Muses (Apollon Musegetes) and director of their choir, Apollo

functioned as the patron god of music and poetry.

Hermes

created the

lyre for him, and the instrument became a common

attribute of Apollo

. Hymns sung to Apollo were

called paeans

.

Apollo (left) and

Artemis

.

Brygos

(potter signed), Tondo of an

Attic red-figure cup c. 470 BC,

Musée du Louvre

.

In Hellenistic times, especially during the 3rd century BCE, as Apollo

Helios he became identified among Greeks with

Helios

,

Titan

god of the sun

, and his sister Artemis

similarly equated with

Selene

, Titan

goddess of the moon

In Latin texts, on the

other hand,

Joseph Fontenrose

declared himself unable to

find any conflation of Apollo with

Sol

among the

Augustan poets

of the 1st century, not even in

the conjurations of Aeneas

and

Latinus

in

Aeneid

XII (161–215). Apollo and Helios/Sol

remained separate beings in literary and mythological texts until the 3rd

century CE.

Origins

The Omphalos

in the Museum of

Delphi

.

The cult centers of Apollo in Greece,

Delphi

and

Delos

, date from the 8th century BCE. The Delos

sanctuary was primarily dedicated to

Artemis

, Apollo’s twin sister. At Delphi,

Apollo was venerated as the slayer of

Pytho

. For the Greeks, Apollo was all the Gods

in one and through the centuries he acquired different functions which could

originate from different gods. In

archaic Greece

he was the

prophet

, the oracular god who in older times

was connected with “healing”. In

classical Greece

he was the god of light and of

music, but in popular religion he had a strong function to keep away evil.

From his eastern-origin Apollo brought the art of inspection from “symbols

and omina

” (σημεία και τέρατα : semeia kai

terata), and of the observation of the

omens of the days. The inspiration oracular-cult was probably

introduced from Anatolia

. The

ritualism

belonged to Apollo from the

beginning. The Greeks created the

legalism

, the supervision of the orders of the

gods, and the demand for moderation and harmony. Apollo became the god of

shining youth, the protector of music, spiritual-life, moderation and

perceptible order. The improvement of the old

Anatolian

god, and his elevation to an

intellectual sphere, may be considered an achievement of the

Greek

people.

Healer and

god-protector from evil

The function of Apollo as a “healer” is connected with

Paean

, the physician of the Gods in the

Iliad

, who seems to come from a more

primitive religion. Paeοn is probably connected with the

Mycenean

Pa-ja-wo, but the etymology is the

only evidence. He did not have a separate cult, but he was the personification

of the holy magic-song sung by the magicians that was supposed to cure disease.

Later the Greeks knew the original meaning of the relevant song “paean”. The

magicians were also called “seer-doctors”, and they used an ecstatic prophetic

art which was used exactly by the god Apollo at the oracles.

In the Iliad, Apollo is the healer under the gods, but he is also the

bringer of disease and death with his arrows, similar to the function of the

terrible

Vedic

god of disease

Rudra

.He sends a terrible plague to the

Achaeans

. The god who sends a disease can also

prevent from it, therefore when it stops they make a purifying ceremony and

offer him an “hecatomb” to ward off evil. When the oath of his priest appeases,

they pray and with a song they call their own god, the beautiful Paean.

Some common epithets of Apollo as a healer are “paion” , “epikourios”,

“oulios”, and “loimios” . In classical times, his strong function in popular

religion was to keep away evil, and was therefore called “apotropaios” and

“alexikakos” , throw away the evil).

In later writers, the word, usually spelled “Paean”, becomes a

mere epithet of Apollo in his capacity as a god of

healing

.

Homer illustrated Paeon the god, and the song both of

apotropaic

thanksgiving or triumph. Such songs

were originally addressed to Apollo, and afterwards to other gods: to

Dionysus

, to Apollo

Helios

, to Apollo’s son

Asclepius

the healer. About the 4th century

BCE, the paean became merely a formula of adulation; its object was either to

implore protection against disease and misfortune, or to offer thanks after such

protection had been rendered. It was in this way that Apollo had become

recognised as the god of music. Apollo’s role as the slayer of the

Python

led to his association with battle and

victory; hence it became the

Roman

custom for a paean to be sung by an army

on the march and before entering into battle, when a fleet left the harbour, and

also after a victory had been won.

Oracular cult

Columns of the

Temple of Apollo

at Delphi, Greece.

Unusually among the Olympic deities, Apollo had two cult sites that had

widespread influence: Delos

and

Delphi

. In cult practice,

Delian Apollo

and

Pythian Apollo

(the Apollo of Delphi) were so

distinct that they might both have shrines in the same locality.Apollo’s

cult

was already fully established when written

sources commenced, about 650 BCE. Apollo became extremely important to the Greek

world as an oracular deity in the

archaic period

, and the frequency of

theophoric names

such as Apollodorus or

Apollonios and cities named Apollonia testify to his popularity.

Oracular sanctuaries to Apollo were established in other sites. In the 2nd and

3rd century CE, those at

Didyma

and

Clarus

pronounced the so-called “theological

oracles”, in which Apollo confirms that all deities are aspects or servants of

an

all-encompassing, highest deity

. “In the 3rd

century, Apollo fell silent.

Julian the Apostate

(359 – 61) tried to revive

the Delphic oracle, but failed

Sardis, also Sardes (Lydian:

Sfard,

Greek

: Σάρδεις,

Persian

: Sparda), modern Sart in the

Manisa

province

of Turkey

, was

the capital of the ancient kingdom of

Lydia

, one of the

important cities of the

Persian Empire

, the seat of a

proconsul

under the

Roman

Empire

, and the metropolis of the province Lydia in later Roman and

Byzantine

times. As one of the

Seven churches of Asia

, it was addressed by the author of the

Book of Revelation

in terms which seem to imply that its population was

notoriously soft and fainthearted. Its importance was due, first to its military

strength, secondly to its situation on an important highway leading from the

interior to the

Aegean

coast, and thirdly to its commanding the wide and fertile plain of the Hermus.

//

Geography

Map of Sardis and Other Cities within the Lydian Empire

Sardis was situated in the middle of

Hermus

valley, at the foot of

Mount Tmolus

, a steep and lofty spur which formed the citadel. It was about

4 kilometres (2.5 mi) south of the Hermus. Today, the site is located by the

present day village of Sart, near

Salihli

in

the Manisa province of Turkey, close to the

Ankara

–

İzmir

highway

(approximately 72 kilometres (45 mi) from

İzmir

). The part

of remains including the bath-gymnasium complex, synagogue and Byzantine shops

is open to visitors year-round.

History

The earliest reference to Sardis is in the

The

Persians

of

Aeschylus

(472 BC); in the Iliad

the name Hyde seems to be given to the city of the

Maeonian

(i.e. Lydian) chiefs, and in later times Hyde was said to be the

older name of Sardis, or the name of its citadel. It is, however, more probable

that Sardis was not the original capital of the Maeonians, but that it became so

amid the changes which produced the powerful Lydian empire of the 8th century

BC.

The city was captured by the

Cimmerians

in the 7th century, by the

Persians

and by the

Athenians

in

the 6th, and by

Antiochus III the Great

at the end of the 3rd century. In the Persian era

Sardis was conquered by

Cyrus the Great

and formed the end station for the Persian

Royal Road

which began in

Persepolis

,

capital of

Persia

. During the

Ionian Revolt

, the

Athenians

burnt down the city. Sardis remained under Persian domination

until it surrendered to

Alexander the Great

in 334 B.C..

Once at least, under the emperor

Tiberius

,

in 17 AD, it was destroyed by an earthquake; but it was always rebuilt. It was

one of the great cities of western

Asia Minor

until the later Byzantine period.

The early Lydian kingdom was far advanced in the industrial arts and Sardis

was the chief seat of its manufactures. The most important of these trades was

the manufacture and dyeing of delicate woolen stuffs and carpets. The stream

Pactolus

which flowed through the market-place “carried golden sands” in early antiquity,

in reality gold dust out of Mt. Tmolus; later, trade and the organization of

commerce continued to be sources of great wealth. After

Constantinople

became the capital of the East, a new road system grew up

connecting the provinces with the capital. Sardis then lay rather apart from the

great lines of communication and lost some of its importance. It still, however,

retained its titular supremacy and continued to be the seat of the

metropolitan bishop

of the province of Lydia, formed in 295 AD. It is

enumerated as third, after

Ephesus

and

Smyrna

, in the

list of cities of the

Thracesion

thema

given by

Constantine Porphyrogenitus

in the 10th century; but over the next four

centuries it is in the shadow of the provinces of Magnesia-upon-Sipylum and

Philadelphia, which retained their importance in the region.

After 1071 the Hermus valley began to suffer from the inroads of the

Seljuk Turks

but the successes of the general

Philokales

in 1118 relieved the district and the ability of the

Comneni

dynasty together with the gradual decay of the

Seljuk Sultanate of Rum

retained it under Byzantine dominion. When

Constantinople

was taken by the

Venetians

and Franks

in 1204 Sardis came under the rule of the Byzantine

Empire of Nicea

. However once the Byzantines retook Constantinople in 1261,

Sardis with the entire

Asia Minor

was neglected and the region eventually fell under the control of

Ghazi (Ghazw)

emirs, the

Cayster

valleys and a fort on the citadel of Sardis was handed over to them

by treaty in 1306. The city continued its decline until its capture (and

probable destruction) by the

Mongol

warlord Timur

in 1402.

Archaeological

expeditions

By the nineteenth century, Sardis was in ruins, showing construction chiefly

of the Roman period. The first large scale archaeological expedition in Sardis

was directed by a

Princeton University

team between years 1910 – 1914, unearthing the Temple

of Artemis, and more than a thousand Lydian tombs. The excavation campaign was

halted by World War I

, followed by the

Turkish War of Independence

. Some surviving artifacts from the Butler

excavation were added to the collection of the

Metropolitan Museum of Art

in

New York

.

The excavation is currently under the directorship of Nick Cahill, professor

at the

University of Wisconsin–Madison

. 4[citation

needed]The laws governing archaeological expeditions in Turkey

ensure that all archaeological artifacts remain in Turkey. Some of the important

finds from the site of Sardis are housed in the

Archaeological Museum of Manisa

, including Late Roman mosaics and sculpture,

a helmet from the mid-6th century BC, and pottery from various periods.

Sardis

synagogue

Since 1958, both

Harvard

and

Cornell Universities

have sponsored annual archeological expeditions to

Sardis. These excavations unearthed perhaps the most impressive synagogue in the

western diaspora yet discovered from antiquity, yielding over eighty Greek and

seven Hebrew inscriptions as well as numerous mosaic floors. (For evidence in

the east, see

Dura Europos

in Syria

.) The discovery of the Sardis synagogue has reversed previous

assumptions about Judaism in the later Roman empire. Along with the discovery of

the godfearers

/theosebeis inscription from the

Aphrodisias

, it provides indisputable evidence for the continued vitality of

Jewish communities in Asia Minor, their integration into general Roman imperial

civic life, and their size and importance at a time when many scholars

previously assumed that Christianity had eclipsed Judaism.[

neededcitation]

The synagogue was a section of a large bath-gymnasium complex, that was in

use for about 450 – 500 years. In the beginning, middle of the second century

AD, the rooms the synagogue is situated in were used as changing rooms or

resting rooms. The complex was destroyed in 616 AD by the Sassanian-Persians.

The history of

Ancient Greek

coinage can be divided (along

with most other Greek art forms) into four periods, the

Archaic

, the

Classical

, the

Hellenistic

and the

Roman

. The Archaic period extends from the

introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the

7th century BC

until the

Persian Wars

in about 480 BC. The Classical

period then began, and lasted until the conquests of

Alexander the Great

in about 330 BC, which

began the Hellenistic period, extending until the

Roman

absorption of the Greek world in the 1st

century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several

more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are

called

Roman provincial coins

or Greek Imperial Coins.

Ancient Greek coins of all four periods span over a period of more than ten

centuries.

Weight

standards and denominations

Above: Six rod-shaped obeloi (oboloi) displayed at the

Numismatic Museum of Athens

,

discovered at

Heraion of Argos

. Below: grasp[1]

of six oboloi forming one drachma

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC, known as

Phanes’ coin

. Obverse:

Stag

grazing, ΦΑΝΕΩΣ (retrograde).

Reverse: Two incuse punches.

The basic standards of the Ancient Greek monetary system were the

Attic

standard, based on the Athenian

drachma

of 4.3 grams of silver and the

Corinthian

standard based on the

stater

of 8.6 grams of silver, that was

subdivided into three silver drachmas of 2.9 grams. The word

drachm

(a) means “a handful”, literally “a

grasp”. Drachmae were divided into six

obols

(from the Greek word for a

spit

), and six spits made a “handful”. This

suggests that before coinage came to be used in Greece, spits in

prehistoric times

were used as measures of

daily transaction. In archaic/pre-numismatic times iron was valued for making

durable tools and weapons, and its casting in spit form may have actually

represented a form of transportable

bullion

, which eventually became bulky and

inconvenient after the adoption of precious metals. Because of this very aspect,

Spartan

legislation famously forbade issuance

of Spartan coin, and enforced the continued use of iron spits so as to

discourage avarice and the hoarding of wealth. In addition to its original

meaning (which also gave the

euphemistic

diminutive

“obelisk“,

“little spit”), the word obol (ὀβολός, obolós, or ὀβελός,

obelós) was retained as a Greek word for coins of small value, still used as

such in Modern Greek

slang (όβολα, óvola,

“monies”).

The obol was further subdivided into tetartemorioi (singular

tetartemorion) which represented 1/4 of an obol, or 1/24 of a drachm. This

coin (which was known to have been struck in

Athens

,

Colophon

, and several other cities) is

mentioned by Aristotle

as the smallest silver coin.:237

Various multiples of this denomination were also struck, including the

trihemitetartemorion (literally three half-tetartemorioi) valued at 3/8 of

an obol.:

| Denominations of silver drachma |

| Image |

Denomination |

Value |

Weight |

|

|

Dekadrachm |

10 drachmas |

43 grams |

|

|

Tetradrachm |

4 drachmas |

17.2 grams |

|

|

Didrachm |

2 drachmas |

8.6 grams |

|

|

Drachma |

6 obols |

4.3 grams |

|

|

Tetrobol |

4 obols |

2.85 grams |

|

|

Triobol (hemidrachm) |

3 obols |

2.15 grams |

|

|

Diobol |

2 obols |

1.43 grams |

|

|

Obol |

4 tetartemorions |

0.72 grams |

|

|

Tritartemorion |

3 tetartemorions |

0.54 grams |

|

|

Hemiobol |

2 tetartemorions |

0.36 grams |

|

|

Trihemitartemorion |

3/2 tetartemorions |

0.27 grams |

|

|

Tetartemorion |

|

0.18 grams |

|

|

Hemitartemorion |

½ tetartemorion |

0.09 grams |

Archaic period

Archaic coinage

Uninscribed

electrum

coin from

Lydia

, 6th century BCE.

Obverse: lion head and sunburst Reverse: plain square

imprints, probably used to standardise weight

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC. Obverse:

Forepart of stag. Reverse: Square incuse punch.

The first coins were issued in either Lydia or Ionia in Asia Minor at some

time before 600 BC, either by the non-Greek Lydians for their own use or perhaps

because Greek mercenaries wanted to be paid in precious metal at the conclusion

of their time of service, and wanted to have their payments marked in a way that

would authenticate them. These coins were made of

electrum

, an alloy of gold and silver that was

highly prized and abundant in that area. By the middle of the 6th century BC,

technology had advanced, making the production of pure gold and silver coins

simpler. Accordingly, King

Croesus

introduced a bi-metallic standard that

allowed for coins of pure gold and pure silver to be struck and traded in the

marketplace.

Coins of Aegina

Silver

stater

of Aegina, 550-530 BC.

Obv.

Sea turtle

with large pellets

down center. Rev. incuse square with eight sections. After the

end of the

Peloponnesian War

, 404 BC, Sea

turtle was replaced by the land

tortoise

.

Silver

drachma

of Aegina, 404-340 BC.

Obverse: Land

tortoise

. Reverse: inscription

AΙΓ[INAΤΟΝ] ([of the] Aeg[inetans]) “Aegina” and dolphin.

The Greek world was divided into more than two thousand self-governing

city-states (in

Greek

, poleis), and more than half of

them issued their own coins. Some coins circulated widely beyond their polis,

indicating that they were being used in inter-city trade; the first example

appears to have been the silver stater or didrachm of

Aegina

that regularly turns up in hoards in

Egypt

and the

Levant

, places which were deficient in silver

supply. As such coins circulated more widely, other cities began to mint coins

to this “Aeginetan” weight standard of (6.1 grams to the drachm), other cities

included their own symbols on the coins. This is not unlike present day

Euro coins, which are recognisably from a particular country, but

usable all over the

Euro zone

.

Athenian coins, however, were struck on the “Attic” standard, with a drachm

equaling 4.3 grams of silver. Over time, Athens’ plentiful supply of silver from

the mines at

Laurion

and its increasing dominance in trade

made this the pre-eminent standard. These coins, known as “owls” because of

their central design feature, were also minted to an extremely tight standard of

purity and weight. This contributed to their success as the premier trade coin

of their era. Tetradrachms on this weight standard continued to be a widely used

coin (often the most widely used) through the classical period. By the time of

Alexander the Great

and his

Hellenistic successors

, this large denomination

was being regularly used to make large payments, or was often saved for

hoarding.

Classical period

A

Syracusan

tetradrachm

(c. 415–405

BC)

Obverse: head of the

nymph

Arethusa

, surrounded by

four swimming

dolphins

and a

rudder

Reverse: a racing

quadriga

, its

charioteer

crowned by the

goddess

Victory

in flight.

Tetradrachm of Athens, (5th century BC)

Obverse: a portrait of

Athena

, patron goddess of

the city, in

helmet

Reverse: the owl of Athens, with an

olive

sprig and the

inscription “ΑΘΕ”, short for ΑΘΕΝΑΙΟΝ, “of the

Athenians

“

The

Classical period

saw Greek coinage reach a high

level of technical and aesthetic quality. Larger cities now produced a range of

fine silver and gold coins, most bearing a portrait of their patron god or

goddess or a legendary hero on one side, and a symbol of the city on the other.

Some coins employed a visual pun: some coins from

Rhodes

featured a

rose, since the Greek word for rose is rhodon. The use of

inscriptions on coins also began, usually the name of the issuing city.

The wealthy cities of Sicily produced some especially fine coins. The large

silver decadrachm (10-drachm) coin from

Syracuse

is regarded by many collectors as the

finest coin produced in the ancient world, perhaps ever. Syracusan issues were

rather standard in their imprints, one side bearing the head of the nymph

Arethusa

and the other usually a victorious

quadriga

. The

tyrants of Syracuse

were fabulously rich, and

part of their

public relations

policy was to fund

quadrigas

for the

Olympic chariot race

, a very expensive

undertaking. As they were often able to finance more than one quadriga at a

time, they were frequent victors in this highly prestigious event.

Syracuse was one of the epicenters of numismatic art during the classical

period. Led by the engravers Kimon and Euainetos, Syracuse produced some of the

finest coin designs of antiquity.

Hellenistic period

Gold 20-stater

of

Eucratides I

, the largest gold coin

ever minted in Antiquity.

Drachma of

Alexandria

, 222-235 AD. Obverse:

Laureate head of

Alexander Severus

, KAI(ΣΑΡ)

MAP(ΚΟΣ) AYP(ΗΛΙΟΣ) ΣЄY(ΑΣΤΟΣ) AΛЄΞANΔPOΣ ЄYΣЄ(ΒΗΣ). Reverse: Bust

of

Asclepius

.

The Hellenistic period was characterized by the spread of Greek

culture across a large part of the known world. Greek-speaking kingdoms were

established in Egypt

and

Syria

, and for a time also in

Iran and as far east as what is now

Afghanistan

and northwestern

India

. Greek traders spread Greek coins across

this vast area, and the new kingdoms soon began to produce their own coins.

Because these kingdoms were much larger and wealthier than the Greek city states

of the classical period, their coins tended to be more mass-produced, as well as

larger, and more frequently in gold. They often lacked the aesthetic delicacy of

coins of the earlier period.

Still, some of the

Greco-Bactrian

coins, and those of their

successors in India, the

Indo-Greeks

, are considered the finest examples

of

Greek numismatic art

with “a nice blend of

realism and idealization”, including the largest coins to be minted in the

Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by

Eucratides

(reigned 171–145 BC), the largest

silver coin by the Indo-Greek king

Amyntas Nikator

(reigned c. 95–90 BC). The

portraits “show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland

depictions of their royal contemporaries further West” (Roger Ling, “Greece and

the Hellenistic World”).

The most striking new feature of Hellenistic coins was the use of portraits

of living people, namely of the kings themselves. This practice had begun in

Sicily, but was disapproved of by other Greeks as showing

hubris

(arrogance). But the kings of

Ptolemaic Egypt

and

Seleucid Syria

had no such scruples: having

already awarded themselves with “divine” status, they issued magnificent gold

coins adorned with their own portraits, with the symbols of their state on the

reverse. The names of the kings were frequently inscribed on the coin as well.

This established a pattern for coins which has persisted ever since: a portrait

of the king, usually in profile and striking a heroic pose, on the obverse, with

his name beside him, and a coat of arms or other symbol of state on the reverse.

Minting

All Greek coins were

handmade

, rather than machined as modern coins

are. The design for the obverse was carved (in

incuso

) into a block of bronze or possibly

iron, called a

die

. The design of the reverse was carved into

a similar punch. A blank disk of gold, silver, or electrum was cast in a mold

and then, placed between these two and the punch struck hard with a hammer,

raising the design on both sides of the coin.

Coins as

a symbol of the city-state

Coins of Greek city-states depicted a unique

symbol

or feature, an early form of

emblem

, also known as

badge

in numismatics, that represented their

city and promoted the prestige of their state. Corinthian stater for example

depicted pegasus

the mythological winged stallion, tamed

by their hero

Bellerophon

. Coins of

Ephesus

depicted the

bee

sacred to

Artemis

. Drachmas of Athens depicted the

owl of Athena

. Drachmas of

Aegina

depicted a

chelone

. Coins of

Selinunte

depicted a “selinon” (σέλινον

– celery

). Coins of

Heraclea

depicted

Heracles

. Coins of

Gela depicted a man-headed bull, the personification of the river

Gela

. Coins of

Rhodes

depicted a “rhodon” (ῥόδον[8]

– rose

). Coins of

Knossos

depicted the

labyrinth

or the mythical creature

minotaur

, a symbol of the

Minoan Crete

. Coins of

Melos

depicted a “mēlon” (μήλον –

apple

). Coins of

Thebes

depicted a Boeotian shield.

Corinthian stater with

pegasus

Coin of

Rhodes

with a

rose

Didrachm of

Selinunte

with a

celery

Coin of

Ephesus

with a

bee

Stater of

Olympia

depicting

Nike

Coin of

Melos

with an

apple

Obolus from

Stymphalia

with a

Stymphalian bird

Coin of

Thebes

with a Boeotian shield

Coin of Gela

with a man-headed bull,

the personification of the river

Gela

Didrachm of

Knossos

depicting the

Minotaur

Commemorative coins

Dekadrachm

of

Syracuse

[disambiguation

needed]. Head of Arethusa or queen

Demarete. ΣΥΡΑΚΟΣΙΟΝ (of the Syracusians), around four dolphins

The use of

commemorative coins

to celebrate a victory or

an achievement of the state was a Greek invention. Coins are valuable, durable

and pass through many hands. In an age without newspapers or other mass media,

they were an ideal way of disseminating a political message. The first such coin

was a commemorative decadrachm issued by

Athens

following the Greek victory in the

Persian Wars

. On these coins that were struck

around 480 BC, the owl

of Athens, the goddess

Athena

‘s sacred bird, was depicted facing the

viewer with wings outstretched, holding a spray of olive leaves, the

olive tree

being Athena’s sacred plant and also

a symbol of peace and prosperity. The message was that Athens was powerful and

victorious, but also peace-loving. Another commemorative coin, a silver

dekadrachm known as ” Demareteion”, was minted at

Syracuse

at approximately the same time to

celebrate the defeat of the

Carthaginians

. On the obverse it bears a

portrait of

Arethusa

or queen Demarete.

Ancient Greek coins

today

Collections of Ancient Greek coins are held by museums around the world, of

which the collections of the

British Museum

, the

American Numismatic Society

, and the

Danish National Museum

are considered to be the

finest. The American Numismatic Society collection comprises some 100,000

ancient Greek coins from many regions and mints, from Spain and North Africa to

Afghanistan. To varying degrees, these coins are available for study by

academics and researchers.

There is also an active collector market for Greek coins. Several auction

houses in Europe and the United States specialize in ancient coins (including

Greek) and there is also a large on-line market for such coins.

Hoards of Greek coins are still being found in Europe, Middle East, and North

Africa, and some of the coins in these hoards find their way onto the market.

Coins are the only art form from the Ancient world which is common enough and

durable enough to be within the reach of ordinary collectors.

|