|

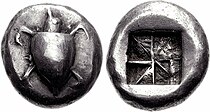

Greek City of Selge in Psidia

Bronze 14mm (2.24 grams) Struck circa 150-50 B.C.

Reference: Sear 5489; B.M.C. 19.261,38-9

Head of bearded Hercules three-quarter face to right, wreathed with styrax; club

in in field to left.

Forepart of stag right, looking back; ΣE-Λ in

field.

The principal city of Pisidia, Selge was situated on the

Eurymedon river about 25 miles north of Aspendos. Its wealth derived from the

fertility of the surrounding country, and its inhabitants who claimed descent

from the Lakedaimonians, were the most warlike in Pisidia.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

HERCULES – This celebrated

of mythological romance was at first called Alcides, but received the name of

Hercules, or Heracles, from the Pythia of Delphos. Feigned by the poets of

antiquity to have been a son of “the Thunderer,” but born of an earthly mother,

he was exposed, through Juno’s implacable hatred to him as the offspring of

Alemena, to a course of perils, which commenced whilst he was yet in his cradle,

and under each of which he seemed to perish, but as constantly proved

victorious.

At

length finishing his allotted career with native valor and generosity, though

too frequently the submissive agent of the meanness and injustice of others, he

perished self-devotedly on the funeral pile, which was lighted on Mount Oeta.

Jupiter raised his heroic progeny to the skies; and Hercules was honored by the

pagan world, as the most illustrious of deified mortals. The extraordinary

enterprises cruelly imposed upon, but gloriously achieved, by this famous

demigod, are to be found depicted, not only on Greek coins, but also on the

Roman series both consular and imperial. The first, and one of the most

dangerous, of undertakings, well-known under the name of the twelve labors of

Hercules, was that of killing the huge lion of Nemea; on which account the

intrepid warrior is represented, clothes in the skin of that forest monarch; he

also bears uniformly a massive club, sometimes without any other arms, but at

others with a bow and quiver of arrows. On a denarius of the Antia gens he is

represented walking with trophy and club.

When his head alone is typified, as in Mucia gens, it is covered with the lion’s

spoils, in which distinctive decoration he was imitated by many princes, and

especially by those who claimed descent from him – as for example, the kings of

Macedonia, and the successors of Alexander the Great. Among the Roman emperors

Trajan is the first whose coins exhibit the figure and attributes of Hercules.

Selge (in

Greek/font>

Σελγη) was an important city in

Pisidia

, on

the southern slope of

Mount Taurus

, at the part where the river

Eurymedon River

forces its way through the mountains towards the south.

The town was believed to be a

Greek colony

, for

Strabo

states that it was founded by

Spartans

, but

adds the somewhat unintelligible remark that previously it had been founded by

Calchas

. The

acropolis

of Selge bore the name of Kesbedion.

The district in which the town was situated was extremely fertile, producing

abundance of oil and wine, but the town itself was difficult of access, being

surrounded by precipices and beds of torrents flowing towards the Eurymedon and

Cestrus (today Aksu)

, and requiring bridges to make them passable. In

consequence of its excellent laws and political constitution, Selge rose to the

rank of the most powerful and populous city of Pisidia, and at one time was able

to send an army of 20,000 men into the field. Owing to these circumstances, and

the valour of its inhabitants, for which they were regarded as worthy kinsmen of

the Spartans, the Selgians were never subject to any foreign power, but remained

in the enjoyment of their own freedom and independence. When

Alexander the Great

passed through Pisidia (333 BC), Selge sent an embassy

to him and gained his favour and friendship.

At that time they were at war with

Termessos

.

At the period when

Achaeus

had made himself master of Western Asia, Selge were at war with

Pednelissus

, which was besieged by them; and Achaeus, on the invitation of

Pednelissus, sent a large force against Selge (218 BC). After a long and

vigorous siege, the Selgians, being betrayed and despairing of resisting Achaeus

any longer, sent deputies to sue for peace, which was granted to them on the

following terms: they agreed to pay immediately 400

talents

, to restore the prisoners of Pednelissus, and after a time to pay

300 talents in addition.

We now have for a long time no particulars about the history of Selge; in the

5th century AD Zosimus

calls it indeed a little town, but it was still strong enough to repel a body of

Goths

. It is

strange that

Pliny

does not notice Selge, for we know from its coins that it was still a

flourishing town in the time of

Hadrian

; and

it is also mentioned in

Ptolemy

and

Hierocles

. Independently of wine and oil, the country about Selge was rich

in timber, and a variety of trees, among which the

storax

was much

valued from its yielding a strong perfume. Selge was also celebrated for an

ointment prepared from the iris root.

The remains of the city consist mainly of parts of the encircling wall and of

the acropolis. A few traces have survived of the

gymnasium

, the stoa

,

the stadium

and the basilica

. There are also the outlines of two temples, but the best conserved

monument is the

theater

, restored in the 3rd century AD.

Halfway on the road to Selge from the

Pamphylian

coastal plain,

a well-preserved Roman Bridge

crosses the deep

Eurymedon

valley.

The history of

Ancient Greek

coinage can be divided (along

with most other Greek art forms) into four periods, the

Archaic

, the

Classical

, the

Hellenistic

and the

Roman

. The Archaic period extends from the

introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the

7th century BC

until the

Persian Wars

in about 480 BC. The Classical

period then began, and lasted until the conquests of

Alexander the Great

in about 330 BC, which

began the Hellenistic period, extending until the

Roman

absorption of the Greek world in the 1st

century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several

more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are

called

Roman provincial coins

or Greek Imperial Coins.

Ancient Greek coins of all four periods span over a period of more than ten

centuries.

Weight

standards and denominations

Above: Six rod-shaped obeloi (oboloi) displayed at the

Numismatic Museum of Athens

,

discovered at

Heraion of Argos

. Below: grasp[1]

of six oboloi forming one drachma

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC, known as

Phanes’ coin

. Obverse:

Stag

grazing, ΦΑΝΕΩΣ (retrograde).

Reverse: Two incuse punches.

The basic standards of the Ancient Greek monetary system were the

Attic

standard, based on the Athenian

drachma

of 4.3 grams of silver and the

Corinthian

standard based on the

stater

of 8.6 grams of silver, that was

subdivided into three silver drachmas of 2.9 grams. The word

drachm

(a) means “a handful”, literally “a

grasp”. Drachmae were divided into six

obols

(from the Greek word for a

spit

), and six spits made a “handful”. This

suggests that before coinage came to be used in Greece, spits in

prehistoric times

were used as measures of

daily transaction. In archaic/pre-numismatic times iron was valued for making

durable tools and weapons, and its casting in spit form may have actually

represented a form of transportable

bullion

, which eventually became bulky and

inconvenient after the adoption of precious metals. Because of this very aspect,

Spartan

legislation famously forbade issuance

of Spartan coin, and enforced the continued use of iron spits so as to

discourage avarice and the hoarding of wealth. In addition to its original

meaning (which also gave the

euphemistic

diminutive

“obelisk“,

“little spit”), the word obol (ὀβολός, obolós, or ὀβελός,

obelós) was retained as a Greek word for coins of small value, still used as

such in Modern Greek

slang (όβολα, óvola,

“monies”).

The obol was further subdivided into tetartemorioi (singular

tetartemorion) which represented 1/4 of an obol, or 1/24 of a drachm. This

coin (which was known to have been struck in

Athens

,

Colophon

, and several other cities) is

mentioned by Aristotle

as the smallest silver coin.:237

Various multiples of this denomination were also struck, including the

trihemitetartemorion (literally three half-tetartemorioi) valued at 3/8 of

an obol.:

| Denominations of silver drachma |

| Image |

Denomination |

Value |

Weight |

|

|

Dekadrachm |

10 drachmas |

43 grams |

|

|

Tetradrachm |

4 drachmas |

17.2 grams |

|

|

Didrachm |

2 drachmas |

8.6 grams |

|

|

Drachma |

6 obols |

4.3 grams |

|

|

Tetrobol |

4 obols |

2.85 grams |

|

|

Triobol (hemidrachm) |

3 obols |

2.15 grams |

|

|

Diobol |

2 obols |

1.43 grams |

|

|

Obol |

4 tetartemorions |

0.72 grams |

|

|

Tritartemorion |

3 tetartemorions |

0.54 grams |

|

|

Hemiobol |

2 tetartemorions |

0.36 grams |

|

|

Trihemitartemorion |

3/2 tetartemorions |

0.27 grams |

|

|

Tetartemorion |

|

0.18 grams |

|

|

Hemitartemorion |

½ tetartemorion |

0.09 grams |

Archaic period

Archaic coinage

Uninscribed

electrum

coin from

Lydia

, 6th century BCE.

Obverse: lion head and sunburst Reverse: plain square

imprints, probably used to standardise weight

Electrum

coin from

Ephesus

, 620-600 BC. Obverse:

Forepart of stag. Reverse: Square incuse punch.

The first coins were issued in either Lydia or Ionia in Asia Minor at some

time before 600 BC, either by the non-Greek Lydians for their own use or perhaps

because Greek mercenaries wanted to be paid in precious metal at the conclusion

of their time of service, and wanted to have their payments marked in a way that

would authenticate them. These coins were made of

electrum

, an alloy of gold and silver that was

highly prized and abundant in that area. By the middle of the 6th century BC,

technology had advanced, making the production of pure gold and silver coins

simpler. Accordingly, King

Croesus

introduced a bi-metallic standard that

allowed for coins of pure gold and pure silver to be struck and traded in the

marketplace.

Coins of Aegina

Silver

stater

of Aegina, 550-530 BC.

Obv.

Sea turtle

with large pellets

down center. Rev. incuse square with eight sections. After the

end of the

Peloponnesian War

, 404 BC, Sea

turtle was replaced by the land

tortoise

.

Silver

drachma

of Aegina, 404-340 BC.

Obverse: Land

tortoise

. Reverse: inscription

AΙΓ[INAΤΟΝ] ([of the] Aeg[inetans]) “Aegina” and dolphin.

The Greek world was divided into more than two thousand self-governing

city-states (in

Greek

, poleis), and more than half of

them issued their own coins. Some coins circulated widely beyond their polis,

indicating that they were being used in inter-city trade; the first example

appears to have been the silver stater or didrachm of

Aegina

that regularly turns up in hoards in

Egypt

and the

Levant

, places which were deficient in silver

supply. As such coins circulated more widely, other cities began to mint coins

to this “Aeginetan” weight standard of (6.1 grams to the drachm), other cities

included their own symbols on the coins. This is not unlike present day

Euro coins, which are recognisably from a particular country, but

usable all over the

Euro zone

.

Athenian coins, however, were struck on the “Attic” standard, with a drachm

equaling 4.3 grams of silver. Over time, Athens’ plentiful supply of silver from

the mines at

Laurion

and its increasing dominance in trade

made this the pre-eminent standard. These coins, known as “owls” because of

their central design feature, were also minted to an extremely tight standard of

purity and weight. This contributed to their success as the premier trade coin

of their era. Tetradrachms on this weight standard continued to be a widely used

coin (often the most widely used) through the classical period. By the time of

Alexander the Great

and his

Hellenistic successors

, this large denomination

was being regularly used to make large payments, or was often saved for

hoarding.

Classical period

A

Syracusan

tetradrachm

(c. 415–405

BC)

Obverse: head of the

nymph

Arethusa

, surrounded by

four swimming

dolphins

and a

rudder

Reverse: a racing

quadriga

, its

charioteer

crowned by the

goddess

Victory

in flight.

Tetradrachm of Athens, (5th century BC)

Obverse: a portrait of

Athena

, patron goddess of

the city, in

helmet

Reverse: the owl of Athens, with an

olive

sprig and the

inscription “ΑΘΕ”, short for ΑΘΕΝΑΙΟΝ, “of the

Athenians

“

The

Classical period

saw Greek coinage reach a high

level of technical and aesthetic quality. Larger cities now produced a range of

fine silver and gold coins, most bearing a portrait of their patron god or

goddess or a legendary hero on one side, and a symbol of the city on the other.

Some coins employed a visual pun: some coins from

Rhodes

featured a

rose, since the Greek word for rose is rhodon. The use of

inscriptions on coins also began, usually the name of the issuing city.

The wealthy cities of Sicily produced some especially fine coins. The large

silver decadrachm (10-drachm) coin from

Syracuse

is regarded by many collectors as the

finest coin produced in the ancient world, perhaps ever. Syracusan issues were

rather standard in their imprints, one side bearing the head of the nymph

Arethusa

and the other usually a victorious

quadriga

. The

tyrants of Syracuse

were fabulously rich, and

part of their

public relations

policy was to fund

quadrigas

for the

Olympic chariot race

, a very expensive

undertaking. As they were often able to finance more than one quadriga at a

time, they were frequent victors in this highly prestigious event.

Syracuse was one of the epicenters of numismatic art during the classical

period. Led by the engravers Kimon and Euainetos, Syracuse produced some of the

finest coin designs of antiquity.

Hellenistic period

Gold 20-stater

of

Eucratides I

, the largest gold coin

ever minted in Antiquity.

Drachma of

Alexandria

, 222-235 AD. Obverse:

Laureate head of

Alexander Severus

, KAI(ΣΑΡ)

MAP(ΚΟΣ) AYP(ΗΛΙΟΣ) ΣЄY(ΑΣΤΟΣ) AΛЄΞANΔPOΣ ЄYΣЄ(ΒΗΣ). Reverse: Bust

of

Asclepius

.

The Hellenistic period was characterized by the spread of Greek

culture across a large part of the known world. Greek-speaking kingdoms were

established in Egypt

and

Syria

, and for a time also in

Iran and as far east as what is now

Afghanistan

and northwestern

India

. Greek traders spread Greek coins across

this vast area, and the new kingdoms soon began to produce their own coins.

Because these kingdoms were much larger and wealthier than the Greek city states

of the classical period, their coins tended to be more mass-produced, as well as

larger, and more frequently in gold. They often lacked the aesthetic delicacy of

coins of the earlier period.

Still, some of the

Greco-Bactrian

coins, and those of their

successors in India, the

Indo-Greeks

, are considered the finest examples

of

Greek numismatic art

with “a nice blend of

realism and idealization”, including the largest coins to be minted in the

Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by

Eucratides

(reigned 171–145 BC), the largest

silver coin by the Indo-Greek king

Amyntas Nikator

(reigned c. 95–90 BC). The

portraits “show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland

depictions of their royal contemporaries further West” (Roger Ling, “Greece and

the Hellenistic World”).

The most striking new feature of Hellenistic coins was the use of portraits

of living people, namely of the kings themselves. This practice had begun in

Sicily, but was disapproved of by other Greeks as showing

hubris

(arrogance). But the kings of

Ptolemaic Egypt

and

Seleucid Syria

had no such scruples: having

already awarded themselves with “divine” status, they issued magnificent gold

coins adorned with their own portraits, with the symbols of their state on the

reverse. The names of the kings were frequently inscribed on the coin as well.

This established a pattern for coins which has persisted ever since: a portrait

of the king, usually in profile and striking a heroic pose, on the obverse, with

his name beside him, and a coat of arms or other symbol of state on the reverse.

Minting

All Greek coins were

handmade

, rather than machined as modern coins

are. The design for the obverse was carved (in

incuso

) into a block of bronze or possibly

iron, called a

die

. The design of the reverse was carved into

a similar punch. A blank disk of gold, silver, or electrum was cast in a mold

and then, placed between these two and the punch struck hard with a hammer,

raising the design on both sides of the coin.

Coins as

a symbol of the city-state

Coins of Greek city-states depicted a unique

symbol

or feature, an early form of

emblem

, also known as

badge

in numismatics, that represented their

city and promoted the prestige of their state. Corinthian stater for example

depicted pegasus

the mythological winged stallion, tamed

by their hero

Bellerophon

. Coins of

Ephesus

depicted the

bee

sacred to

Artemis

. Drachmas of Athens depicted the

owl of Athena

. Drachmas of

Aegina

depicted a

chelone

. Coins of

Selinunte

depicted a “selinon” (σέλινον

– celery

). Coins of

Heraclea

depicted

Heracles

. Coins of

Gela depicted a man-headed bull, the personification of the river

Gela

. Coins of

Rhodes

depicted a “rhodon” (ῥόδον[8]

– rose

). Coins of

Knossos

depicted the

labyrinth

or the mythical creature

minotaur

, a symbol of the

Minoan Crete

. Coins of

Melos

depicted a “mēlon” (μήλον –

apple

). Coins of

Thebes

depicted a Boeotian shield.

Corinthian stater with

pegasus

Coin of

Rhodes

with a

rose

Didrachm of

Selinunte

with a

celery

Coin of

Ephesus

with a

bee

Stater of

Olympia

depicting

Nike

Coin of

Melos

with an

apple

Obolus from

Stymphalia

with a

Stymphalian bird

Coin of

Thebes

with a Boeotian shield

Coin of Gela

with a man-headed bull,

the personification of the river

Gela

Didrachm of

Knossos

depicting the

Minotaur

Commemorative coins

Dekadrachm

of

Syracuse

[disambiguation

needed]. Head of Arethusa or queen

Demarete. ΣΥΡΑΚΟΣΙΟΝ (of the Syracusians), around four dolphins

The use of

commemorative coins

to celebrate a victory or

an achievement of the state was a Greek invention. Coins are valuable, durable

and pass through many hands. In an age without newspapers or other mass media,

they were an ideal way of disseminating a political message. The first such coin

was a commemorative decadrachm issued by

Athens

following the Greek victory in the

Persian Wars

. On these coins that were struck

around 480 BC, the owl

of Athens, the goddess

Athena

‘s sacred bird, was depicted facing the

viewer with wings outstretched, holding a spray of olive leaves, the

olive tree

being Athena’s sacred plant and also

a symbol of peace and prosperity. The message was that Athens was powerful and

victorious, but also peace-loving. Another commemorative coin, a silver

dekadrachm known as ” Demareteion”, was minted at

Syracuse

at approximately the same time to

celebrate the defeat of the

Carthaginians

. On the obverse it bears a

portrait of

Arethusa

or queen Demarete.

Ancient Greek coins

today

Collections of Ancient Greek coins are held by museums around the world, of

which the collections of the

British Museum

, the

American Numismatic Society

, and the

Danish National Museum

are considered to be the

finest. The American Numismatic Society collection comprises some 100,000

ancient Greek coins from many regions and mints, from Spain and North Africa to

Afghanistan. To varying degrees, these coins are available for study by

academics and researchers.

There is also an active collector market for Greek coins. Several auction

houses in Europe and the United States specialize in ancient coins (including

Greek) and there is also a large on-line market for such coins.

Hoards of Greek coins are still being found in Europe, Middle East, and North

Africa, and some of the coins in these hoards find their way onto the market.

Coins are the only art form from the Ancient world which is common enough and

durable enough to be within the reach of ordinary collectors.

|