|

Severus II – Roman Emperor : 306-307 A.D.

Severus II as Caesar

Bronze Follis 28mm (8.15 grams) Lugdunum mint: 305-307 A.D.

Reference: RIC 193 (Lugdunum)

FLVALSEVERVSNOBC – Laureate, cuirassed bust right.

GENIOPOPVLIROMANI Exe: PLG – Genius standing left, sacrificing over altar

and holding cornucopia.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Head of a genius worshipped by Roman soldiers (found at

Vindobona

, 2nd century CE)

In

ancient Roman religion

, the genius was

the individual instance of a general divine nature that is present in every

individual person, place, or thing.

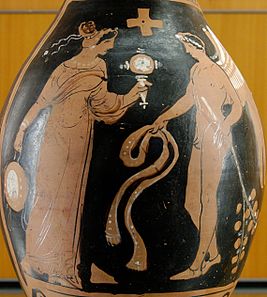

Winged genius facing a woman with a tambourine and mirror, from

southern Italy, about 320 BC.

Nature of the genius

The rational powers and abilities of every human being were attributed to

their soul, which was a genius. Each individual place had a genius

(genius

loci) and so did powerful objects, such as volcanoes. The concept

extended to some specifics: the genius of the theatre, of vineyards, and of

festivals, which made performances successful, grapes grow, and celebrations

succeed, respectively. It was extremely important in the Roman mind to

propitiate the appropriate genii for the major undertakings and events of their

lives.

Specific genii

_01.jpg/170px-Genio_romano_de_Ponte_Puñide_(M.A.N._1928-60-1)_01.jpg)

Bronze genius depicted as

pater familias

(1st century CE)

Although the term genius might apply to any divinity whatsoever, most

of the higher-level and state genii had their own well-established names.

Genius applied most often to individual places or people not generally

known; that is, to the smallest units of society and settlements, families and

their homes. Houses, doors, gates, streets, districts, tribes, each one had its

own genius.The supreme hierarchy of the Roman gods, like that of the

Greeks, was modelled after a human family. It featured a father,

Jupiter

(“father god”), who, in a

patriarchal society

was also the supreme divine

unity, and a mother,

Juno

, queen of the gods. These supreme

unities were subdivided into genii for each individual family; hence, the

genius of each female, representing the female domestic reproductive

power, was a Juno. The male function was a Jupiter.

The juno was worshipped under many titles:

- Iugalis, “of marriage”

- Matronalis, “of married women”

- Pronuba, “of brides”

- Virginalis, “of virginity”

Genii were often viewed as protective spirits, as one would propitiate

them for protection. For example, to protect infants one propitiated a number of

deities concerned with birth and childrearing

:

Cuba (“lying down to sleep”), Cunina (“of the cradle”) and

Rumina (“of breast-feeding”). Certainly, if those genii did not

perform their proper function well, the infant would be in danger.

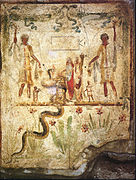

Hundreds of lararia, or family shrines, have been discovered at

Pompeii

, typically off the

atrium

, kitchen or garden, where the smoke

of burnt offerings could vent through the opening in the roof. A lararium

was distinct from the penus (“within”), another shrine where the

penates

, gods associated with the storerooms,

was located. Each lararium features a panel fresco containing the same

theme: two peripheral figures (Lares)

attend on a central figure (family genius) or two figures (genius

and Juno) who may or may not be at an altar. In the foreground is one or

two serpents crawling toward the genius through a meadow motif.

Campania

and

Calabria

preserved an ancient practice of

keeping a propitious house snake, here linked with the genius. In

another, unrelated fresco (House

of the Centenary) the snake-in-meadow appears below a depiction of

Mount Vesuvius

and is labelled Agathodaimon,

“good

daimon

“, where daimon must be regarded

as the Greek equivalent of genius.

History of the concept

Origin

Etymologically

genius

(“household guardian spirit”) has

the same derivation as nature from

gēns

(“tribe”, “people”) from the

Indo-European

root *gen-, “produce.”

It is the indwelling nature of an object or class of objects or

events that act with a perceived or hypothesized unity. Philosophically the

Romans did not find the paradox of the one being many confusing; like all other

prodigies they attributed it to the inexplicable mystery of divinity. Multiple

events could therefore be attributed to the same and different divinities and a

person could be the same as and different from his genius. They were not

distinct, as the later guardian angels, and yet the Genius Augusti was

not exactly the same as Augustus either. As a natural outcome of these

beliefs, the pleasantness of a place, the strength of an oath, an ability of a

person, were regarded as intrinsic to the object, and yet were all attributable

to genius; hence all of the modern meanings of the word. This point of

view is not attributable to any one civilization; its roots are lost in

prehistory. The Etruscans had such beliefs at the beginning of history, but then

so did the Greeks, the native Italics and many other peoples in the near and

middle east.

Genii under the

monarchy

No literature of the monarchy has survived, but later authors in recounting

its legends mention the genius. For example, under

Servius Tullius

the triplets

Horatii

of Rome fought the triplets Curiatii of

Alba Longa

for the decision of the war that had

arisen between the two communities. Horatius was left standing but his sister,

who had been betrothed to one of the Curiatii, began to keen, breast-beat and

berate Horatius. He executed her, was tried for murder, was acquitted by the

Roman people but the king made him expiate the Juno of his sister and the

Genius Curiatii, a family genius.

Republican genii

The genius appears explicitly in Roman literature relatively late as

early as Plautus

, where one character in the play,

Captivi

, jests that the father of another

is so avaricious that he uses cheap Samian ware in sacrifices to his own

genius, so as not to tempt the genius to steal it.In this passage,

the genius is not identical to the person, as to propitiate oneself would

be absurd, and yet the genius also has the avarice of the person; that

is, the same character, the implication being, like person, like genius.

Implied geniuses date to much earlier; for example, when

Horatius Cocles

defends the

Pons Sublicius

against an Etruscan crossing at

the beginning of the

Roman Republic

, after the bridge is cut down he

prays to the Tiber to bear him up as he swims across: Tiberine pater te,

sancte, precor …, “Holy father Tiber, I pray to you ….” The Tiber so

addressed is a genius. Although the word is not used here, in later

literature it is identified as one.

Horace

describes the genius as “the companion which controls the natal star; the god of

human nature, in that he is mortal for each person, with a changing expression,

white or black”.

Imperial genii

Octavius Caesar

on return to Rome after the

final victory of the

Roman Civil War

at the

Battle of Actium

appeared to the Senate to be a

man of great power and success, clearly a mark of divinity. In recognition of

the prodigy they voted that all banquets should include a libation to his

genius. In concession to this sentiment he chose the name

Augustus

, capturing the numinous meaning of

English “august.” This line of thought was probably behind the later vote in 30

BC that he was divine, as the household cult of the Genius Augusti dates

from that time. It was propitiated at every meal along with the other household

numina.The vote began the tradition of the

divine emperors

; however, the divinity went

with the office and not the man. The Roman emperors gave ample evidence that

they personally were neither immortal nor divine.

Inscription on votive altar to the genius of

Legio VII Gemina

by L. Attius Macro

(CIL

II 5083)

If the genius

of the

imperator

, or commander of all troops, was

to be propitiated, so was that of all the units under his command. The

provincial troops expanded the idea of the genii of state; for example,

from Roman Britain have been found altars to the genii of Roma,

Roman aeterna, Britannia, and to every

legion

,

cohors

,

ala

and

centuria

in Britain, as well as to the

praetorium

of every

castra

and even to the

vexillae

. Inscriptional dedications to

genius were not confined to the military. From

Gallia Cisalpina

under the empire are numerous

dedications to the genii of persons of authority and respect; in addition

to the emperor’s genius principis, were the geniuses of patrons of

freedmen, owners of slaves, patrons of guilds, philanthropists, officials,

villages, other divinities, relatives and friends. Sometimes the dedication is

combined with other words, such as “to the genius and honor” or in the case of

couples, “to the genius and Juno.”

Surviving from the time of the empire hundreds of dedicatory, votive and

sepulchral inscriptions ranging over the entire territory testify to a floruit

of genius worship as an official cult. Stock phrases were abbreviated:

GPR, genio populi Romani (“to the genius of the Roman people”); GHL,

genio huius loci (“to the genius of this place”); GDN, genio domini

nostri (“to the genius of our master”), and so on. In 392 AD with the final

victory of Christianity

Theodosius I

declared the worship of the Genii,

Lares

and

Penates

to be treason, ending their official

terms. The concept, however, continued in representation and speech under

different names or with accepted modifications.

Roman iconography

Coins

The genius of a corporate social body is often a

cameo

theme on ancient coins: a

denarius

from Spain, 76-75 BC, featuring a bust

of the GPR (Genius Populi Romani, “Genius of the Roman People”) on

the

obverse

; an

aureus

of

Siscia

in

Croatia

, 270-275 AD, featuring a standing image

of the GENIUS ILLVR (Genius Exercitus Illyriciani, “Genius of the

Illyrian Army”) on the reverse; an

aureus

of Rome, 134-138 AD, with an image of a

youth holding a cornucopia and patera (sacrificial dish) and the inscription

GENIOPR, genio populi Romani, “to the genius of the Roman people,” on the

reverse.

|

|

|

Scene from Lararium, House of Iulius Polybius, Pompeii

|

|

|

|

Agathodaimon

(“good

divinity”), genius of the soil around Vesuvius

|

|

|

|

Unknown Roman genius near Pompeii, 1st century BC

|

|

Modern-era

representations

|

|

|

Genius of love, Meister des Rosenromans, 1420-1430

|

|

|

|

Genius of victory,

Michelangelo

(1475-1564

|

|

|

|

Genius of

Palermo

, Ignazio Marabitti,

c. 1778

|

|

|

|

Genius of liberty,

Augustin Dumont

, 1801-1884

|

|

|

|

Genius of Alexander, Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun,

1814

|

|

|

|

Genius of war, Arturo Melida y Alinara (1849-1902)

|

|

Flavius Valerius Severus (or rarely Severus II)

(died February 307) was a

Western Roman Emperor

from 306 to 307 (1 May

305 – summer 306 (as

Caesar

in the west under

Constantius Chlorus

);

summer 306 – March or April 307 (as

Augustus

in the west, in competition with

Constantine

,

Maxentius

, and

Maximian

).

Severus was of humble birth, born in the

Illyrian

provinces around the middle of the

third century AD. He rose to become a senior officer in the Roman army, and as

an old friend of

Galerius

, that emperor ordered that Severus be

appointed

Caesar

of the

Western Roman Empire

, a post that he succeeded

to on 1 May 305. He thus served as deputy-emperor to

Constantius I

(Constantius

Chlorus),

Augustus

of the western half of empire.

On the death of Constantius I in the summer of 306, Severus

was promoted to Augustus by

Galerius

himself, in opposition to the

acclamation of

Constantine I

(Constantius’ son) by his own

soldiers. When

Maxentius

, the son of the retired emperor

Maximian

, revolted at

Rome, Galerius sent Severus to suppress the rebellion. Severus moved

from his capital,

Mediolanum

, towards Rome, at the head of an

army previously commanded by Maximian. Fearing the arrival of Severus, Maxentius

offered Maximian the co-rule of the empire. Maximian accepted, and when Severus

arrived under the walls of Rome and besieged it, his men deserted him and passed

to Maximian, their old commander. Severus fled to

Ravenna

, an impregnable position: Maximian

offered to spare his life and treat him humanely if the latter surrendered

peaceably, which he did in March or April 307. Despite Maximian’s assurance,

Severus was nonetheless displayed as a captive and later imprisoned at

Tres Tabernae

. When Galerius himself invaded

Italy to suppress Maxentius and Maximian, the former ordered Severus’s death: he

was executed (or forced to commit suicide) on 16 February 307.

|

_01.jpg/170px-Genio_romano_de_Ponte_Puñide_(M.A.N._1928-60-1)_01.jpg)