|

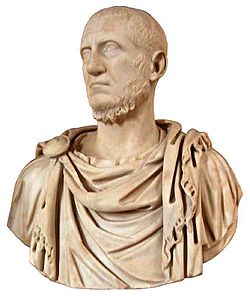

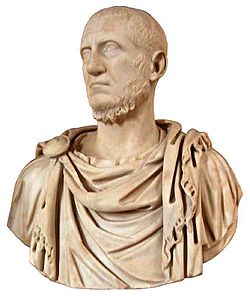

Tacitus – Roman Emperor: 275-276 A.D. –

Bronze Antoninianus 23mm (2.59 grams) Strcuk at the mint of Ticinum circa

275-276 A.D.

Reference: RIC 138

IMP CM CLA TACITVS AVG – Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right.

FELICITAS SAECVLI – Felicitas standing left, sacrificing over altar and holding

caduceus, II in exergue.

You are bidding on the exact

item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime

Guarantee of Authenticity.

In

ancient Roman culture

, felicitas

(from the Latin

adjective

felix, “fruitful, blessed,

happy, lucky”) is a condition of divinely inspired productivity, blessedness, or

happiness

. Felicitas could encompass

both a woman’s fertility, and a general’s luck or good fortune. The divine

personification of Felicitas was

cultivated

as a goddess. Although felicitas

may be translated as “good luck,” and the goddess Felicitas shares some

characteristics and attributes with

Fortuna

, the two were distinguished in

Roman religion

.Fortuna was unpredictable and

her effects could be negative, as the existence of an altar to Mala Fortuna

(“Bad Luck”) acknowledges.Felicitas, however, always had a positive

significance. She appears with

several epithets that focus on aspects of her divine power.

Felicitas had a temple in Rome as early as the mid-2nd century BC, and during

the Republican era

was honored at two

official festivals

of

Roman state religion

, on July 1 in conjunction

with

Juno

and October 9 as Fausta Felicitas.

Felicitas continued to play an important role in

Imperial cult

, and was frequently portrayed on

coins

as a symbol of the wealth and prosperity

of the Roman Empire

. Her primary attributes are the

caduceus

and

cornucopia

.The English word “felicity” derives

from felicitas.

As virtue or quality

Phallic

relief

with the inscription “Felicitas

dwells here”

In its religious sense, felix means “blessed, under the protection or

favour of the gods; happy.” That which is felix has achieved the

pax divom

, a state of harmony or peace with

the divine world.[5]

The word derives from

Indo-European

*dhe(i)l, meaning “happy,

fruitful, productive, full of nourishment.” Related Latin words include

femina, “woman” (a person who provides nourishment or suckles); felo,

“to suckle” in regard to an infant; filius, “son” (a person suckled);[6]

and probably fello, fellare, “to perform

fellatio

“, with an originally non-sexual

meaning of “to suck”.[7]

The continued magical association of sexual potency, increase, and general good

fortune in productivity is indicated by the inscription Hic habitat Felicitas

(“Felicitas dwells here”)[8]

on an

apotropaic

relief of a

phallus

at a bakery in

Pompeii

.[9]

In archaic Roman culture, felicitas was a quality expressing the close

bonds between

religion and agriculture

. Felicitas was

at issue when the

suovetaurilia

sacrifice conducted by

Cato the Elder

as

censor

in 184 BC was challenged as having been

unproductive, perhaps for

vitium

, ritual error.[10]

In the following three years Rome had been plagued by a number of ill omens and

prodigies (prodigia),

such as severe storms, pestilence, and “showers of blood,” which had required a

series of expiations (supplicationes).[11]

The speech Cato gave to justify himself is known as the Oratio de lustri sui

felicitate, “Speech on the Felicitas of his

Lustrum

“, and survives only as a possible

quotation by a later source.[12]

Cato says that a lustrum should be found to have produced felicitas

“if the crops had filled up the storehouses, if the vintage had been abundant,

if the olive oil had flowed deliberately from the groves”,[13]

regardless of whatever else might have occurred. The efficacy of a ritual might

be thus expressed as its felicitas.[14]

The ability to promote felicitas became proof of one’s excellence and

divine favor. Felicitas was simultaneously a divine gift, a quality that

resided within an individual, and a contagious capacity for generating

productive conditions outside oneself:[15]

it was a form of “charismatic

authority”.[16]

Cicero

lists felicitas as one of the

four virtues of the exemplary general, along with knowledge of

military science

(scientia rei militaris),

virtus

(both “valor” and “virtue”), and

auctoritas

, “authority.” Virtus was

a regular complement to felicitas, which was not thought to attach to

those who were unworthy.[17]

Cicero attributed felicitas particularly to

Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”)

,[18]

and distinguished this felicitas even from the divine good luck enjoyed

by successful generals such as

Fabius Maximus

,

Marcellus

,

Scipio the Younger

and

Marius

.[19]

The sayings (sententiae) of

Publilius Syrus

are often attached to divine

qualities, including Felicitas: “The people’s Felicitas is powerful when she is

merciful” (potens misericors publica est Felicitas).[20]

Epithets

Epithets

of Felicitas include:

Augusta

, the goddess in her association

with the emperor and

Imperial cult

.- Fausta (“Favored, Fortunate”), a state divinity

cultivated

on October 9 in conjunction with

Venus Victrix

and the Genius Populi

Romani (“Genius”

of the Roman People, also known as the Genius Publicus).

- Publica, the “public” Felicitas; that is, the aspect of the

divine force that was concerned with the res publica or commonwealth,

or with the Roman People (Populus Romanus).

- Temporum, the Felicitas “of the times”, a title which emphasize

the felicitas being experienced in current circumstances.

Republic

The

cult

of Felicitas is first recorded in the

mid-2nd century BC, when a

temple

was dedicated to her by

Lucius Licinius Lucullus

, grandfather of the

famous Lucullus

, using booty from his military

campaigns in

Spain

in 151–150 BC.[21]

Predecessor to a noted connoisseur of art, Lucullus obtained and dedicated

several statues looted by

Mummius

from

Greece

, including works by

Praxiteles

: the Thespiades, a statue

group of the

Muses

brought from

Thespiae

, and a

Venus

.[22]

This Temple of Felicitas was among several that had a secondary function as art

museums, and was recommended by

Cicero

along with the

Fortuna Huiusce

DieiTemple of

for those who enjoyed viewing art but lacked the means to

amass private collections.[23]

The temple was located in the

Velabrum

in the

Vicus Tuscus

of the

Campus Martius

, along a route associated with

triumphs

: the axle of

Julius Caesar

‘s triumphal

chariot

in 46 BC is supposed to have broken in

front of it.[24]

The temple was destroyed by a fire during the reign of

Claudius

, though the Muses were rescued.[25]

It was not rebuilt at this site.[26]

Sulla identified himself so closely with the quality of felicitcas

that he adopted the

agnomen

(nickname) Felix. His

domination as

dictator

resulted from civil war and

unprecedented military violence within the city of Rome itself, but he

legitimated his authority by claiming that the mere fact of his victory was

proof he was felix and enjoyed the divine favor of the gods. Republican

precedent was to regard a victory as belonging to the Roman people as a whole,

as represented by the

triumphal procession

at which the honored

general submitted public offerings at the

Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

at the

Capitol

, and Sulla thus established an

important theological element for the later authority of the emperor.[27]

Although he established no new temple for Felicitas,[28]

he celebrated games (ludi

circenses) in her honor.[29]

On July 1 and October 9, Felicitas received a sacrifice in Capitolio,

on the

Capitoline Hill

, on the latter date as

Fausta Felicitas in conjunction with the

Genius Publicus

(“Public

Genius

“) and

Venus Victrix

. These observances probably took

place at an altar or small shrine (aedicula),

not a separate

temple precinct

.[30]

The

Acts of the Arval Brothers

(1st century AD)

prescribe a cow as the sacrifice for Felicitas.[31]

Pompey established a shrine for Felicitas at

his new theater and temple complex

, which used

the steps to the Temple of Venus Victrix as seating. Felicitas was cultivated

with Honor

and Virtue, and she may have shared her

shrine there with

Victory

, as she did in the Imperial era as

Felicitas Caesaris (Caesar’s Felicitas) at

Ameria

.[32]

Pompey’s collocation of deities may have been intended to parallel the

Capitoline grouping.[33]

A fourth cult site for Felicitas in Rome had been planned by Caesar, and

possibly begun before his death. Work on the temple was finished by

Lepidus

on the site of the

Curia Hostilia

, which had been restored by

Sulla, destroyed by fire in 52 BC,[34]

and demolished by Caesar in 44 BC.[35]

This temple seems not to have existed by the time of

Hadrian

. Its site probably lies under the

church of

Santi Luca e Martina

.[36]

It has been suggested that an

Ionic capital

and a

tufa wall uncovered at the site are the only known remains of the

temple.[37]

Felicitas was a

watchword

used by Julius Caesar’s troops at the

Battle of Thapsus

,[38]

the names of deities and divine personifications being often recorded for this

purpose in the late Republic.[39]

Felicitas Iulia

(“Julian Felicitas”) was

the name of a

colony

in

Roman Spain

that was refounded under Caesar and

known also as Olisipo

, present-day

Lisbon

, Portugal.[40]

During the Republic, only divine personifications known to have had a temple

or public altar were featured on coins, among them Felicitas.[41]

On the only extant Republican coin type, Felicitas appears as a bust and wearing

a diadem

.[42]

Empire

Felicitas Temporum represented by a pair of cornucopiae on a

denarius

(193-194 AD) issued under

Pescennius Niger

A calendar from Cumae

records that a

supplicatio

was celebrated on April 16 for

the Felicitas of the Empire, in honor of the day

Augustus

was first acclaimed

imperator

.[43]

In extant Roman coinage, Felicitas appears with a

caduceus

only during the Imperial period.[44]

The earliest known example is Felicitas Publica on a

dupondius

issued under

Galba

.[45]

Felicitas Temporum (“Prosperity of the Times”), reflecting a

Golden Age

ideology, was among the innovative

virtues that began to appear during the reigns of

Trajan

and

Antoninus Pius

.[46]

Septimius Severus

, whose reign followed the

exceedingly brief tenure of

Pertinax

and unsatisfactory conditions under

Commodus

, used coinage to express his efforts

toward restoring the

Pax Romana

, with themes such as Felicitas

Temporum and Felicitas Saeculi, “Prosperity of the Age” (saeculum),

prevalent in the years 200 to 202.[47]

Some Imperial coins use these phrases with images of women and children in the

emperor’s family.[48]

When the Empire came under Christian rule, the personified virtues that had

been cultivated as deities could be treated as abstract concepts. Felicitas

Perpetua Saeculi (“Perpetual Blessedness of the Age”) appears on a coin

issued under

Constantine

, the first emperor to convert to

Christianity.[

The caduceus from

Greek

“herald’s staff” is the staff carried by

Hermes

in

Greek mythology

. The same staff was also borne

by heralds in general, for example by

Iris

, the messenger of

Hera. It is a short staff entwined by two

serpents

, sometimes surmounted by wings. In

Roman iconography it was often depicted being carried in the left hand of

Mercury

, the messenger of the gods, guide of

the dead and protector of merchants, shepherds, gamblers, liars, and thieves.

As a symbolic object it represents Hermes (or the Roman Mercury), and by

extension trades, occupations or undertakings associated with the god. In later

Antiquity

the caduceus provided the basis for

the

astrological symbol

representing the

planet Mercury

. Thus, through its use in

astrology

and

alchemy

, it has come to denote the

elemental metal

of the same name.

By extension of its association with Mercury/Hermes, the caduceus is also a

recognized symbol of commerce and negotiation, two realms in which balanced

exchange and reciprocity are recognized as ideals.[4][5]

This association is ancient, and consistent from the Classical period to modern

times. The caduceus is also used as a symbol representing printing, again by

extension of the attributes of Mercury (in this case associated with writing and

eloquence).

The caduceus is sometimes mistakenly used

as a symbol of medicine and/or medical practice

,

especially in

North America

, because of widespread confusion

with the traditional medical symbol, the

rod of Asclepius

, which has only a single snake

and no wings.

The term kerukeion denoted any herald’s staff, not necessarily

associated with Hermes in particular.[7]

Lewis Richard Farnell

(1909) in his study of

the cult of Hermes assumed that the two snakes had simply developed out of

ornaments of the shepherd’s crook used by heralds as their staff.[8]

This view has been rejected by later authors pointing to parallel iconography in

the Ancient Near East. It has been argued that the staff or wand entwined by two

snakes was itself representing a god in the pre-anthropomorphic era. Like the

herm

or

priapus

, it would thus be a predecessor of the

anthropomorphic Hermes of the classical era.

Ancient Near East

William Hayes Ward

(1910) discovered that

symbols similar to the classical caduceus sometimes appeared on

Mesopotamian cylinder seals

. He suggested the

symbol originated some time between 3000 and 4000 BCE, and that it might have

been the source of the Greek caduceus.[10]

A.L. Frothingham incorporated Dr. Ward’s research into his own work, published

in 1916, in which he suggested that the prototype of Hermes was an “Oriental

deity of Babylonian extraction” represented in his earliest form as a snake god.

From this perspective, the caduceus was originally representative of Hermes

himself, in his early form as the Underworld god

Ningishzida

, “messenger” of the “Earth Mother”.[11]

The caduceus is mentioned in passing by

Walter Burkert

[12]

as “really the image of copulating snakes taken over from Ancient Near Eastern

tradition”.

In Egyptian iconography, the

Djed pillar is depicted as containing a snake in a frieze of the

Dendera Temple complex

.

The rod of Moses

and the

brazen serpent

are frequently compared to the

caduceus, especially as Moses is acting as a messenger of God to the

Pharaoh

at the point in the narrative where he

changes his staff into a serpent.[13]

Classical antiquity

Mythology

The

Homeric hymn

to Hermes relates how Hermes

offered his lyre fashioned from a tortoise shell as compensation for the

cattle he stole

from his half brother

Apollo

. Apollo in return gave Hermes the

caduceus as a gesture of friendship.[14]

The association with the serpent thus connects Hermes to

Apollo

, as later the serpent was associated

with Asclepius

, the “son of Apollo”.[15]

The association of Apollo with the serpent is a continuation of the older

Indo-European

dragon

-slayer motif.

Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher

(1913) pointed out

that the serpent as an attribute of both Hermes and Asclepius is a variant of

the “pre-historic semi-chthonic serpent hero known at Delphi as

Python

“, who in classical mythology is slain by

Apollo.[16]

One Greek myth of origin

of the caduceus is part of the

story of Tiresias

,[17]

who found two snakes copulating and killed the female with his staff. Tiresias

was immediately turned into a woman, and so remained until he was able to repeat

the act with the male snake seven years later. This staff later came into the

possession of the god Hermes, along with its transformative powers.

Another myth suggests that Hermes (or Mercury) saw two serpents entwined in

mortal combat. Separating them with his wand he brought about peace between

them, and as a result the wand with two serpents came to be seen as a sign of

peace.[18]

In Rome, Livy

refers to the caduceator who

negotiated peace arrangements under the diplomatic protection of the caduceus he

carried.

Iconography

In some vase paintings ancient depictions of the Greek kerukeion are

somewhat different from the commonly seen modern representation. These

representations feature the two snakes atop the staff (or rod), crossed to

create a circle with the heads of the snakes resembling horns. This old graphic

form, with an additional crossbar to the staff, seems to have provided the basis

for the graphical

sign of Mercury

(☿) used in

Greek astrology

from Late Antiquity.[19]

Use in alchemy

and occultism

As the symbol of both the

planet

and the

metal

named for Mercury, the caduceus became an

important symbol in

alchemy

.

The

crucified serpent

was also revived as an

alchemical symbol for

fixatio

, and

John Donne

(Sermons 10:190) uses

“crucified Serpent” as a title of

Jesus Christ

.

Symbol of commerce

A simplified variant of the caduceus is to be found in dictionaries,

indicating a “commercial term” entirely in keeping with the association of

Hermes with commerce. In this form the staff is often depicted with two winglets

attached and the snakes are omitted (or reduced to a small ring in the middle).[20]

The Customs Service of the former

German Democratic Republic

employed the

caduceus, bringing its implied associations with thresholds, translators, and

commerce, in the service medals they issued their staff.

Misuse as symbol

of medicine

It is relatively common, especially in the United States, to find the

caduceus, with its two snakes and wings, used as a symbol of medicine instead of

the correct rod of Asclepius, with only a single snake. This usage is erroneous,

popularised largely as a result of the adoption of the caduceus as its insignia

by the

US Army medical corps

in 1902 at the insistence

of a single officer (though there are conflicting claims as to whether this was

Capt. Frederick P. Reynolds or Col. John R. van Hoff).[21][22]

The rod of Asclepius is the dominant symbol for professional healthcare

associations in the United States. One survey found that 62% of professional

healthcare associations used the rod of Asclepius as their symbol.[23]

The same survey found that 76% of commercial healthcare organizations used the

Caduceus symbol. The author of the study suggests the difference exists because

professional associations are more likely to have a real understanding of the

two symbols, whereas commercial organizations are more likely to be concerned

with the visual impact a symbol will have in selling their products.

The initial errors leading to its adoption and the continuing confusion it

generates are well known to medical historians. The long-standing and abundantly

attested historical associations of the caduceus with commerce, theft,

deception, and death are considered by many to be inappropriate in a symbol used

by those engaged in the healing arts.[22]

This has occasioned significant criticism of the use of the caduceus in a

medical context.

Marcus Claudius Tacitus (ca. 200 – June 276) was a

Roman Emperor

from September 25 275, to June 276.

Biography

He was born in Interamna

(Terni), in

Italia

. He circulated copies of the historian

Gaius Cornelius Tacitus

‘ work, which was barely read at the time, and so we

perhaps have him to thank for the partial survival of Tacitus’ work; however,

modern historiography

rejects his claimed descent from the historian as forgery. In the course of his

long life he discharged the duties of various civil offices, including that of

consul

in 273,

with universal respect.

After the assassination of

Aurelian

,

he was chosen by the

Senate

to succeed him, and the choice was cordially ratified by the army. His first

action was to move against the barbarian tribes that had been gathered by

Aurelian for his Eastern campaign, and which had plundered the Eastern Roman

provinces after Aurelian had been murdered and the campaign cancelled. His

half-brother, the Praetorian Prefect

Florianus

,

and Tacitus himself won a victory against these tribes, among which

Heruli

, which

granted the emperor the title Gothicus Maximus.

Tacitus probably died of fever (according to

Aurelius Victor

,

Eutropius

and the

Historia Augusta

) – though

Zosimus

claims he was assassinated – at

Tyana

in

Cappadocia

in June 276.

|