|

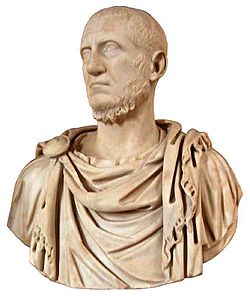

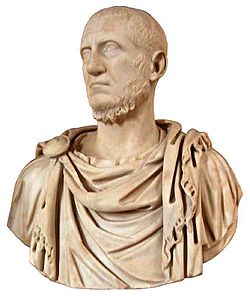

Tacitus – Roman Emperor: 275-276 A.D.

Silvered Bronze Antoninianus 22mm (3.65 grams) Struck circa 275-276 A.D.

Reference: RIC 140, rad,dr,cuir; Sear5 11775.

IMP CM CL TACITVS AVG, radiate, draped cuirassed bust right

FELICIT TEMP or variant, Felicitas standing left with caduceus and scepter.

Officina letter V in ex. .

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The caduceus (“herald’s wand, or staff”) is the staff carried by Hermes in Greek mythology and consequently by Hermes Trismegistus in Greco-Egyptian mythology. The same staff was also borne by heralds in general, for example by Iris, the messenger of Hera. It is a short staff entwined by two serpents, sometimes surmounted by wings. In Roman iconography, it was often depicted being carried in the left hand of Mercury, the messenger of the gods, guide of the dead and protector of merchants, shepherds, gamblers, liars, and thieves. The caduceus (“herald’s wand, or staff”) is the staff carried by Hermes in Greek mythology and consequently by Hermes Trismegistus in Greco-Egyptian mythology. The same staff was also borne by heralds in general, for example by Iris, the messenger of Hera. It is a short staff entwined by two serpents, sometimes surmounted by wings. In Roman iconography, it was often depicted being carried in the left hand of Mercury, the messenger of the gods, guide of the dead and protector of merchants, shepherds, gamblers, liars, and thieves.

Some accounts suggest that the oldest known imagery of the caduceus have their roots in a Mesopotamian origin with the Sumerian god Ningishzida whose symbol, a staff with two snakes intertwined around it, dates back to 4000 B.C. to 3000 B.C.

As a symbolic object, it represents Hermes (or the Roman Mercury), and by extension trades, occupations, or undertakings associated with the god. In later Antiquity, the caduceus provided the basis for the astrological symbol representing the planet Mercury. Thus, through its use in astrology and alchemy, it has come to denote the elemental metal of the same name. It is said the wand would wake the sleeping and send the awake to sleep. If applied to the dying, their death was gentle; if applied to the dead, they returned to life.

By extension of its association with Mercury and Hermes, the caduceus is also a recognized symbol of commerce and negotiation, two realms in which balanced exchange and reciprocity are recognized as ideals. This association is ancient, and consistent from the Classical period to modern times. The caduceus is also used as a symbol representing printing, again by extension of the attributes of Mercury (in this case associated with writing and eloquence).

The caduceus is often incorrectly used, particularly in North America, as a symbol of healthcare organizations and medical practice, due to confusion with the traditional medical symbol, the rod of Asclepius, which has only one snake and is never depicted with wings.

In ancient Roman culture, felicitas (from the Latin adjective felix, “fruitful, blessed, happy, lucky”) is a condition of divinely inspired productivity, blessedness, or happiness. Felicitas could encompass both a woman’s fertility, and a general’s luck or good fortune. The divine personification of Felicitas was cultivated as a goddess. Although felicitas may be translated as “good luck,” and the goddess Felicitas shares some characteristics and attributes with Fortuna, the two were distinguished in Roman religion. Fortuna was unpredictable and her effects could be negative, as the existence of an altar to Mala Fortuna (“Bad Luck”) acknowledges. Felicitas, however, always had a positive significance. She appears with several epithets that focus on aspects of her divine power.

Felicitas had a temple in Rome as early as the mid-2nd century BC, and during the Republican era was honored at two official festivals of Roman state religion, on July 1 in conjunction with Juno and October 9 as Fausta Felicitas. Felicitas continued to play an important role in Imperial cult, and was frequently portrayed on coins as a symbol of the wealth and prosperity of the Roman Empire. Her primary attributes are the caduceus and cornucopia. The English word “felicity” derives from felicitas.

As virtue or quality

In its religious sense, felix means “blessed, under the protection or favour of the gods; happy.” That which is felix has achieved the pax divom, a state of harmony or peace with the divine world. The word derives from Indo-European *dhe(i)l, meaning “happy, fruitful, productive, full of nourishment.” Related Latin words include femina, “woman” (a person who provides nourishment or suckles); felo, “to suckle” in regard to an infant; filius, “son” (a person suckled); and probably fello, fellare, “to perform fellatio”, with an originally non-sexual meaning of “to suck”. The continued magical association of sexual potency, increase, and general good fortune in productivity is indicated by the inscription Hic habitat Felicitas (“Felicitas dwells here”) on an apotropaic relief of a phallus at a bakery in Pompeii.

In archaic Roman culture, felicitas was a quality expressing the close bonds between religion and agriculture. Felicitas was at issue when the suovetaurilia sacrifice conducted by Cato the Elder as censor in 184 BC was challenged as having been unproductive, perhaps for vitium, ritual error. In the following three years Rome had been plagued by a number of ill omens and prodigies (prodigia), such as severe storms, pestilence, and “showers of blood,” which had required a series of expiations (supplicationes). The speech Cato gave to justify himself is known as the Oratio de lustri sui felicitate, “Speech on the Felicitas of his Lustrum”, and survives only as a possible quotation by a later source. Cato says that a lustrum should be found to have produced felicitas “if the crops had filled up the storehouses, if the vintage had been abundant, if the olive oil had flowed deliberately from the groves”, regardless of whatever else might have occurred. The efficacy of a ritual might be thus expressed as its felicitas.

The ability to promote felicitas became proof of one’s excellence and divine favor. Felicitas was simultaneously a divine gift, a quality that resided within an individual, and a contagious capacity for generating productive conditions outside oneself: it was a form of “charismatic authority”. Cicero lists felicitas as one of the four virtues of the exemplary general, along with knowledge of military science (scientia rei militaris), virtus (both “valor” and “virtue”), and auctoritas, “authority.” Virtus was a regular complement to felicitas, which was not thought to attach to those who were unworthy. Cicero attributed felicitas particularly to Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”), and distinguished this felicitas even from the divine good luck enjoyed by successful generals such as Fabius Maximus, Marcellus, Scipio the Younger and Marius.

The sayings (sententiae) of Publilius Syrus are often attached to divine qualities, including Felicitas: “The people’s Felicitas is powerful when she is merciful” (potens misericors publica est Felicitas).

Epithets

Epithets of Felicitas include:

- Augusta, the goddess in her association with the emperor and Imperial cult.

- Fausta (“Favored, Fortunate”), a state divinity cultivated on October 9 in conjunction with Venus Victrix and the Genius Populi Romani (“Genius” of the Roman People, also known as the Genius Publicus).

- Publica, the “public” Felicitas; that is, the aspect of the divine force that was concerned with the res publica or commonwealth, or with the Roman People (Populus Romanus).

- Temporum, the Felicitas “of the times”, a title which emphasize the felicitas being experienced in current circumstances.

Marcus Claudius Tacitus (ca. 200 – June 276) was a Roman Emperor from September 25 275, to June 276. Marcus Claudius Tacitus (ca. 200 – June 276) was a Roman Emperor from September 25 275, to June 276.

He was born in Interamna (Terni), in Italia. He circulated copies of the historian Gaius Cornelius Tacitus’ work, which was barely read at the time, and so we perhaps have him to thank for the partial survival of Tacitus’ work; however, modern historiography rejects his claimed descent from the historian as forgery. In the course of his long life he discharged the duties of various civil offices, including that of consul in 273, with universal respect.

After the assassination of Aurelian, he was chosen by the Senate to succeed him, and the choice was cordially ratified by the army. His first action was to move against the barbarian tribes that had been gathered by Aurelian for his Eastern campaign, and which had plundered the Eastern Roman provinces after Aurelian had been murdered and the campaign cancelled. His half-brother, the Praetorian Prefect Florianus, and Tacitus himself won a victory against these tribes, among which Heruli, which granted the emperor the title Gothicus Maximus.

Tacitus probably died of fever (according to Aurelius Victor, Eutropius and the Historia Augusta) – though Zosimus claims he was assassinated – at Tyana in Cappadocia in June 276.

|

The caduceus (“herald’s wand, or staff”) is the staff carried by Hermes in Greek mythology and consequently by Hermes Trismegistus in Greco-Egyptian mythology. The same staff was also borne by heralds in general, for example by Iris, the messenger of Hera. It is a short staff entwined by two serpents, sometimes surmounted by wings. In Roman iconography, it was often depicted being carried in the left hand of Mercury, the messenger of the gods, guide of the dead and protector of merchants, shepherds, gamblers, liars, and thieves.

The caduceus (“herald’s wand, or staff”) is the staff carried by Hermes in Greek mythology and consequently by Hermes Trismegistus in Greco-Egyptian mythology. The same staff was also borne by heralds in general, for example by Iris, the messenger of Hera. It is a short staff entwined by two serpents, sometimes surmounted by wings. In Roman iconography, it was often depicted being carried in the left hand of Mercury, the messenger of the gods, guide of the dead and protector of merchants, shepherds, gamblers, liars, and thieves. Marcus Claudius Tacitus (ca. 200 – June 276) was a Roman Emperor from September 25 275, to June 276.

Marcus Claudius Tacitus (ca. 200 – June 276) was a Roman Emperor from September 25 275, to June 276.