|

Trajan

–

Roman Emperor

: 98-117 A.D. –

Bronze Quadrans 15mm (1.06 grams) Rome mint: 98-117 A.D.

Reference: RIC 702; sear5 #3248; RIC 702; Cohen 341

IMP CAES TRAIAN AVG GERM, diademed bust of Hercules right with lion-skin

on neck.

Boar walking right, SC in exergue.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

The Calydonian Boar is one of the monsters of

Greek mythology

that had to be overcome by

heroes of the Olympian age. Sent by

Artemis

to ravage the region of

Calydon

in

Aetolia

because its king failed to honor her in

his rites to the gods, it was killed in the Calydonian Hunt, in which

many male heroes took part, but also a powerful woman,

Atalanta

, who won its hide by first wounding it

with an arrow. This outraged some of the men, with tragic results.

Strabo

was under the impression that the

Calydonian Boar was an offspring of the

Crommyonian Sow

vanquished by

Theseus

.

The Calydonian Hunt shown on a Roman frieze (Ashmolean

Museum,

Oxford

)

Importance in Greek mythology and art

The Calydonian Boar is one of the

chthonic

monsters in Greek mythology, each set

in a specific locale. Sent by Artemis to ravage the region of Calydon in

Aetolia

, it met its end in the Calydonian

Hunt, in which all the heroes of the new age pressed to take part, with the

exception of Heracles

, who vanquished his own Goddess-sent

Erymanthian Boar

separately. Since the mythic

event drew together numerous heroes—among whom were many who were venerated as

progenitors of their local ruling houses among tribal groups of

Hellenes

into Classical times—the Calydonian

Boar hunt offered a natural subject in classical art, for it was redolent with

the web of myth that gathered around its protagonists on other occasions, around

their half-divine descent and their offspring. Like the quest for the

Golden Fleece

(Argonautica)

or the Trojan War

that took place the following

generation, the Calydonian Hunt is one of the nodes in which much Greek myth

comes together.

Tondo of a

Laconian

black-figure cup

by the

Naucratis Painter

, ca. 555 BCE (Louvre)

Both Homer

and

Hesiod

and their listeners were aware of the

details of this myth, but no surviving complete account exists: some

papyrus

fragments found at

Oxyrhynchus

are all that survive of

Stesichorus

‘ telling; the myth repertory called

Bibliotheke

(“The Library”) contains the

gist of the tale, and before that was compiled the Roman poet Ovid told the

story in some colorful detail in his

Metamorphoses

.

Hunt

King Oeneus

(“wine man”) of

Calydon

, an ancient city of west-central

Greece

north of the

Gulf of Patras

, held annual harvest sacrifices

to the gods on the sacred hill. One year the king forgot to include Great “Artemis

of the Golden Throne” in his offerings Insulted, Artemis, the “Lady of the Bow”,

loosed the biggest, most ferocious boar imaginable on the countryside of

Calydon. It rampaged throughout the countryside, destroying vineyards and crops,

forcing people to take refuge inside the city walls (Ovid), where they began to

starve.

Oeneus sent messengers out to look for the best hunters in Greece, offering

them the boar’s pelt and tusks as a prize.

Roman marble sarcophagus from

Vicovaro

, carved with the Calydonian Hunt (Palazzo

dei Conservatori, Rome)

Meleager et Atalanta, after

Giulio Romano

..

Among those who responded were some of the

Meleager

Argonauts

, and, remarkably for the Hunt’s

eventual success, one woman— the huntress

Atalanta

, the “indomitable”, who had been

suckled by Artemis as a she-bear and raised as a huntress, a proxy for Artemis

herself (Kerenyi; Ruck and Staples). Artemis appears to have been divided in her

motives, for it was also said that she had sent the young huntress because she

knew her presence would be a source of division, and so it was: many of the men,

led by Kepheus and Ankaios, refused to hunt alongside a woman. It was the

smitten Meleager who convinced them. Nonetheless it was Atalanta who first

succeeded in wounding the boar with an arrow, although Meleager finished it off,

and offered the prize to Atalanta, who had drawn first blood. But the sons of

Thestios, who considered it disgraceful that a woman should get the trophy where

men were involved, took the skin from her, saying that it was properly theirs by

right of birth, if Meleagros chose not to accept it. Outraged by this, Meleagros

slew the sons of Thestios and again gave the skin to Atalanta (Bibliotheke).

Meleager’s mother, sister of Meleager’s slain uncles, took the fatal brand from

the chest where she had kept it (see

Meleager

) and threw it once more on the fire;

as it was consumed, Meleager died on the spot, as the Fates had foretold. Thus

Artemis achieved her revenge against King Oeneus.

Woodcut illustration for

Raphael Regius

‘s edition of

Metamorphoses

,

Venice

, ca. 1518

During the hunt, Peleus

accidentally killed his host Eurytion.

In the course of the hunt and its aftermath, many of the hunters turned upon one

another, contesting the spoils, and so the Goddess continued to be revenged (Kerenyi,

114): “But the goddess again made a great stir of anger and crying battle, over

the head of the boar and the bristling boar’s hide, between

Kouretes

and the high-hearted

Aitolians

” ((Homer,

Iliad

, ix.543).

Athena Alae at

Tegea

in

Laconia

was reputedly that of the Calydonian

Boar, “rotted by age and by now altogether without bristles” by the time

Pausanias

saw it in the second century CE. He

noted that the tusks had been taken to Rome as booty from the defeated allies of

Mark Anthony

by

Augustus

; “one of the tusks of the Calydonian

boar has been broken”, Pausanias reports, “but the remaining one, having a

circumference of about half a fathom, was dedicated in the Emperor’s gardens, in

a shrine of Dionysos”. The Calydonian Hunt was the theme of the temple’s main

pediment.

Herculess is the Roman name for the Greek

divine

hero Heracles

, who was the son of

Zeus (Roman equivalent

Jupiter

) and the mortal

Alcmene

. In

classical mythology

, Hercules is famous for his

strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Greek hero’s iconography and myths for their

literature and art under the name Hercules. In later

Western art

and literature and in

popular culture

, Hercules is more

commonly used than Heracles as the name of the hero. Hercules was a

multifaceted figure with contradictory characteristics, which enabled later

artists and writers to pick and choose how to represent him. This article

provides an introduction to representations of Hercules in the

later tradition

.

Labours

Hercules is known for his many adventures, which took him to the far reaches

of the

Greco-Roman world

. One cycle of these

adventures became

canonical

as the “Twelve Labours,” but the list

has variations. One traditional order of the labours is found in the

Bibliotheca

as follows:

- Slay the

Nemean Lion

.

- Slay the nine-headed

Lernaean Hydra

.

- Capture the

Golden Hind of Artemis

.

- Capture the

Erymanthian Boar

.

- Clean the Augean

stables in a single day.

- Slay the

Stymphalian Birds

.

- Capture the

Cretan Bull

.

- Steal the

Mares of Diomedes

.

- Obtain the girdle of

Hippolyta

, Queen of the

Amazons

.

- Obtain the cattle of the monster

Geryon

.

- Steal the apples of the

Hesperides

.

- Capture and bring back

Cerberus

.

The Latin

name Hercules was borrowed through

Etruscan

, where it is represented variously as

Heracle

, Hercle, and other forms. Hercules was

a favorite subject for

Etruscan art

, and appears often on

bronze mirrors

. The Etruscan form Herceler

derives from the Greek Heracles via

syncope

. A mild oath invoking Hercules (Hercule!

or Mehercle!) was a common

interjection

in

Classical Latin

.

Baby Hercules strangling a

snake

sent to

kill him in his

cradle

(Roman marble, 2nd century CE)

Hercules had a number of

myths

that were distinctly Roman. One of these

is Hercules’ defeat of

Cacus

, who was terrorizing the countryside of

Rome. The hero was associated with the

Aventine Hill

through his son

Aventinus

.

Mark Antony

considered him a personal patron

god, as did the emperor

Commodus

. Hercules received various forms of

religious veneration

, including as a

deity concerned with children and childbirth

,

in part because of myths about his precocious infancy, and in part because he

fathered countless children. Roman brides wore a special belt tied with the “knot

of Hercules“, which was supposed to be hard to untie.[4]

The comic playwright

Plautus

presents the myth of Hercules’

conception as a sex comedy in his play

Amphitryon

;

Seneca

wrote the tragedy Hercules Furens

about his bout with madness. During the

Roman Imperial era

, Hercules was worshipped

locally from Hispania

through

Gaul.

Medieval mythography

After the Roman Empire became

Christianized

, mythological narratives were

often reinterpreted as

allegory

, influenced by the philosophy of

late antiquity

. In the 4th century,

Servius

had described Hercules’ return from the

underworld as representing his ability to overcome earthly desires and vices, or

the earth itself as a consumer of bodies. In medieval mythography, Hercules was

one of the heroes seen as a strong role model who demonstrated both valor and

wisdom, with the monsters he battles as moral obstacles. One

glossator

noted that when

Hercules became a constellation

, he showed that

strength was necessary to gain entrance to Heaven.

Medieval mythography was written almost entirely in Latin, and original Greek

texts were little used as sources for Hercules’ myths.

Renaissance

mythography

The Renaissance

and the invention of the

printing press

brought a renewed interest in

and publication of Greek literature. Renaissance mythography drew more

extensively on the Greek tradition of Heracles, typically under the Romanized

name Hercules, or the alternate name

Alcides

. In a chapter of his book

Mythologiae (1567), the influential mythographer

Natale Conti

collected and summarized an

extensive range of myths concerning the birth, adventures, and death of the hero

under his Roman name Hercules. Conti begins his lengthy chapter on Hercules with

an overview description that continues the moralizing impulse of the Middle

Ages:

Hercules, who subdued and destroyed monsters, bandits, and criminals, was

justly famous and renowned for his great courage. His great and glorious

reputation was worldwide, and so firmly entrenched that he’ll always be

remembered. In fact the ancients honored him with his own temples, altars,

ceremonies, and priests. But it was his wisdom and great soul that earned

those honors; noble blood, physical strength, and political power just

aren’t good enough.

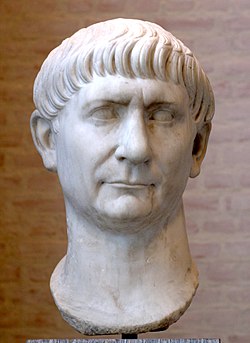

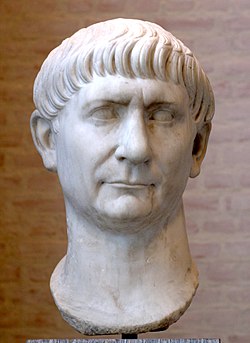

Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus, commonly known as Trajan (18

September, 53 – 8 August, 117), was a

Roman Roman

Emperor who reigned from AD 98 until his death in AD 117. Born Marcus Ulpius Traianus into a non-patrician

family

in the

Hispania Baetica

province (modern day

Spain

), Trajan

rose to prominence during the reign of emperor

Domitian

,

serving as a general in the

Roman army

along the

German frontier

, and successfully crushing the revolt of

Antonius Saturninus

in 89. On September 18, 96, Domitian was succeeded by

Marcus Cocceius Nerva

,

an old and childless senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a

brief and tumultuous year in power, a revolt by members of the

Praetorian Guard

compelled him to adopt the more popular Trajan as his heir

and successor. Nerva died on January 27, 98, and was succeeded by his adopted

son without incident.

As a civilian administrator, Trajan is best known for his extensive public

building program, which reshaped the city of

Rome and left

multiple enduring landmarks such as

Trajan’s Forum

,

Trajan’s Market

and

Trajan’s Column

. It was as a military commander however that Trajan

celebrated his greatest

triumphs

. In 101, he launched a

punitive expedition

into the kingdom of

Dacia

against

king Decebalus

, defeating the Dacian army near

Tapae

in 102, and finally conquering Dacia completely in 106. In 107, Trajan

pushed further east and annexed the

Nabataean kingdom

, establishing the province of

Arabia Petraea

. After a period of relative peace within the Empire, he

launched his final campaign in 113 against

Parthia

,

advancing as far as the city of

Susa in 116, and

expanding the Roman Empire to its greatest extent. During this campaign Trajan

was struck by illness, and late in 117, while sailing back to Rome, he died of a

stroke

on

August 9

,

in the city of

Selinus

. He was

deified

by the Senate and his ashes were laid to rest under

Trajan’s Column

. He was succeeded by his adopted son (not having a

biological heir) Publius Aelius Hadrianus

—commonly known as Hadrian.

As an emperor, Trajan’s reputation has endured – he is one of the few rulers

whose reputation has survived the scrutiny of nineteen centuries of history.

Every new emperor after him was honoured by the Senate with the prayer

felicior Augusto, melior Traiano, meaning “may he be luckier than

Augustus

and better than Trajan”. Among

medieval

Christian theologians, Trajan was considered a

virtuous pagan

, while the 18th century historian

Edward Gibbon

popularized the notion of the

Five Good Emperors

, of which Trajan was the second.

Early life and

rise to power

Trajan was born on September 18, 53 in the Roman province of

Hispania Baetica

(in what is now

Andalusia

in modern Spain), a province that was thoroughly Romanized and called southern

Hispania, in the city of

Italica

,

where the

Italian

families were paramount. Of

Italian

stock himself, Trajan is frequently but misleadingly designated the

first provincial emperor.

Trajan was the son of

Marcia

and

Marcus Ulpius Traianus

, a prominent

senator

and general from the famous

Ulpia

gens.

Trajan himself was just one of many well-known Ulpii in a line that continued

long after his own death. His elder sister was

Ulpia Marciana

and his niece was

Salonina Matidia

. The

patria

of

the Ulpii was Italica

, in Spanish Baetica,

where their ancestors had settled late in the third century B.C. This indicates

that the Italian origin was paramount, yet it has recently been cogently argued

that the family’s ancestry was local, with Trajan senior actually a Traius who

was adopted into the family of the Ulpii.

As a young man, he rose through the ranks of the

Roman army

,

serving in some of the most contentious parts of the Empire’s frontier. In

76–77, Trajan’s father was

Governor

of

Syria

(Legatus

pro praetore Syriae), where Trajan himself remained as

Tribunus

legionis. Trajan was nominated as

Consul

and

brought

Apollodorus of Damascus

with him to

Rome around 91.

Along the

Rhine River

, he took part in the Emperor

Domitian

‘s

wars while under Domitian’s successor,

Nerva

, who was

unpopular with the army and needed to do something to gain their support. He

accomplished this by naming Trajan as his adoptive son and successor in the

summer of 97. According to the

Augustan History

, it was the future Emperor

Hadrian

who

brought word to Trajan of his adoption.

When Nerva died on January 27, 98, the highly respected Trajan succeeded without

incident.

His

reign

The new Roman emperor was greeted by the people of Rome with great

enthusiasm, which he justified by governing well and without the bloodiness that

had marked Domitian’s reign. He freed many people who had been unjustly

imprisoned by Domitian and returned a great deal of private property that

Domitian had confiscated; a process begun by Nerva before his death. His

popularity was such that the

Roman

Senate eventually bestowed upon Trajan the

honorific

of optimus, meaning “the best”.

Dio Cassius, sometimes known as Dio, reveals that Trajan drank heartily and

was involved

with boys. “I know, of course, that he was devoted to boys and to wine, but

if he had ever committed or endured any base or wicked deed as the result of

this, he would have incurred censure; as it was, however, he drank all the wine

he wanted, yet remained sober, and in his relation with boys he harmed no one.”

This sensibility was one that influenced his governing on at least one occasion,

leading him to favour the king of Edessa out of appreciation for his handsome

son: “On this occasion, however,

Abgarus, induced partly by the persuasions of his son Arbandes, who was

handsome and in the pride of youth and therefore in favour with Trajan, and

partly by his fear of the latter’s presence, he met him on the road, made his

apologies and obtained pardon, for he had a powerful intercessor in the boy.”

Dacian

Wars

Main article:

Trajan’s Dacian Wars

It was as a military commander that Trajan is best known to history,

particularly for his conquests in the

Near East,

but initially for the two wars against

Dacia — the

reduction to client kingdom (101-102), followed by actual incorporation to the

Empire of the trans-Danube border kingdom of Dacia—an area that had troubled

Roman thought for over a decade with the unfavourable (and to some, shameful)

peace negotiated by

Domitian’s

ministers

In the first war c. March–May 101, he launched a vicious attack into the kingdom

of Dacia with

four legions,

crossing to the northern bank of the

Danube River on a stone bridge he had built, and defeating the Dacian army

near or in a

mountain pass called

Tapae (see

Second Battle of Tapae). Trajan’s troops were mauled in the encounter,

however and he put off further campaigning for the year to heal troops,

reinforce, and regroup.

During the following winter, King

Decebalus

launched a counter-attack across the

Danube further

downstream, but this was repulsed. Trajan’s army advanced further into Dacian

territory and forced King Decebalus to submit to him a year later, after Trajan

took the Dacian capital/fortress of

Sarmizegethusa. The Emperor Domitian had campaigned against

Dacia from 86 to 87 without securing a decisive outcome, and Decebalus had

brazenly flouted the terms of the peace (89 AD) which had been agreed on

conclusion of this campaign.

Trajan now returned to Rome in triumph and was granted the title Dacicus

Maximus. The victory was celebrated by the

Tropaeum Traiani. Decebalus though, after being left to his own devices, in

105 undertook an invasion against Roman territory by attempting to stir up some

of the tribes north of the river against her.

Trajan took to the field again and after building with the design of

Apollodorus of Damascus his

massive bridge over the Danube, he conquered Dacia completely in 106.

Sarmizegethusa was destroyed,

Decebalus

committed suicide,

and his severed head was exhibited in Rome on the steps leading up to the

Capitol. Trajan built a new city, “Colonia Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica

Sarmizegetusa”, on another site than the previous Dacian Capital, although

bearing the same full name, Sarmizegetusa. He resettled Dacia with Romans and

annexed it as a province of the Roman Empire. Trajan’s Dacian campaigns

benefited the Empire’s finances through the acquisition of Dacia’s gold mines.

The victory is celebrated by

Trajan’s Column.

Expansion

in the East

At about the same time

Rabbel II Soter, one of Rome’s client kings, died. This event might have

prompted the annexation of the

Nabataean kingdom, although the manner and the formal reasons for the

annexation are unclear. Some epigraphic evidence suggests a military operation,

with forces from

Syria and

Egypt. What is clear, however, is that by 107, Roman legions were stationed

in the area around

Petra and

Bostra, as is shown by a papyrus found in Egypt. The empire gained what

became the province of

Arabia Petraea (modern southern

Jordan and

north west

Saudi

Arabia).

Period

of peace

The next seven years, Trajan ruled as a civilian emperor, to the same acclaim

as before. It was during this time that he corresponded with

Pliny the Younger on the subject of how to deal with the

Christians of

Pontus, telling Pliny to leave them alone unless they were openly practicing

the religion. He built several new buildings, monuments and roads in

Italia and his native

Hispania.

His magnificent complex in Rome raised to commemorate his victories in

Dacia (and

largely financed from that campaign’s loot)—consisting of a

forum,

Trajan’s Column, and Trajan’s Market still stands in Rome today. He was also

a prolific builder of triumphal arches, many of which survive, and rebuilder

of roads (Via

Traiana and

Via Traiana Nova).

One notable act of Trajan was the hosting of a three-month

gladiatorial

festival in the great

Colosseum

in Rome (the precise date of this festival is unknown). Combining chariot

racing, beast fights and close-quarters gladiatorial bloodshed, this gory

spectacle reputedly left 11,000 dead (mostly slaves and criminals, not to

mention the thousands of ferocious beasts killed alongside them) and attracted a

total of five million spectators over the course of the festival.

Another important act was his formalisation of the Alimenta, a welfare

program that helped orphans and poor children throughout Italy. It provided

general funds, as well as food and subsidized education. The program was

supported initially by funds from the Dacian War, and then later by a

combination of estate taxes and philanthropy.[13].

Although the system is well documented in literary sources and contemporary

epigraphy, its precise aims are controversial and have generated considerable

dispute between modern scholars: usually, it’s assumed that the programme

intended to bolster citzen numbers in Italy. However, the fact that it was

subsidized by means of interest payments on loans made by landowners restricted

it to a small percentage of potential welfare recipients (Paul

Veyne has assumed that, in the city of

Veleia, only one child out of ten was an actual beneficiary) – therefore,

the idea, advanced by

Moses I. Finley, that the whole scheme was at most a form of random charity,

a mere imperial benevolence[14].

Maximum

extent of the Empire

The extent of the Roman Empire under Trajan (117)

In 113, he embarked on his last campaign, provoked by

Parthia’s

decision to put an unacceptable king on the throne of

Armenia, a

kingdom over which the two great empires had shared

hegemony

since the time of Nero

some fifty years earlier. Some modern historians also attribute Trajan’s

decision to wage war on Parthia to economic motives: to control, after the

annexation of Arabia, Mesopotamia and the coast of the Persian Gulf, and with it

the sole remaining receiving-end of the Indian trade outside Roman control

– an attribution of motive other historians find absurd, as seeing a commercial

motive in a campaign triggered by the lure of territorial annexation and

prestige

– by the way, the only motive for Trajan’s actions ascribed by Dio Cassius in

his description of the events.

Other modern historians, however, think that Trajan’s original aim was quite

modest: to assure a more defensible Eastern frontier for the Roman Empire,

crossing across Northern Mesopotamia along the course of the river

Khabur in order to offer cover to a Roman Armenia.

Trajan marched first on Armenia, deposed the Parthian-appointed king (who was

afterwards murdered while kept in the custody of Roman troops in an unclear

incident) and annexed it to the Roman Empire as a province, receiving in passing

the acknowledgement of Roman hegemony by various tribes in the Caucasus and on

the Eastern coast of the Black Sea – a process that kept him busy until the end

of 114].

The cronology of subsequent events is uncertain, but it’s generally believed

that early in 115 Trajan turned south into the core Parthian hegemony, taking

the Northern Mesopotamian cities of

Nisibis and

Batnae and organizing a province of

Mesopotamia in the beginning of 116, when coins were issued announcing that

Armenia and Mesopotamia had been put under the authority of the Roman people.

In early 116, however, Trajan began to toy with the conquest of the whole of

Mesopotamia, an overambitious goal that eventually backfired on the results of

his entire campaign: One Roman division crossed the

Tigris into

Adiabene, sweeping South and capturing

Adenystrae; a second followed the river South, capturing

Babylon;

while Trajan himself sailed down the

Euphrates, then dragged his fleet overland into the Tigris, capturing

Seleucia and finally the Parthian capital of

Ctesiphon.

He continued southward to the

Persian

Gulf, receiving the submission of Athambelus, the ruler of

Charax, whence he declared Babylon a new province of the Empire, sent the

Senate a laurelled letter declaring the war to be at a close and lamented that

he was too old to follow in the steps of

Alexander the Great and reach the distant

India

itself.

A province of

Assyria was also proclaimed, apparently covering the territory of Adiabene,

as well as some measures seem to have been considered about the fiscal

administration of the Indian trade.

However, as Trajan left the Persian Gulf for Babylon – where he intended to

offer sacrifice to Alexander in the house where he had died in 323 B.C.-

a sudden outburst of Parthian resistance, led by a nephew of the Parthian king,

Sanatrukes, imperilled Roman positions in Mesopotamia and Armenia, something

Trajan sought to deal with by forsaking direct Roman rule in Parthia proper, at

least partially: later in 116, after defeating a Parthian army in a battle where

Sanatrukes was killed and re-taking Seleucia, he formally deposed the Parthian

king

Osroes I and put his own puppet ruler

Parthamaspates on the throne. That done, he retreated North in order to

retain what he could of the new provinces of Armenia and Mesopotamia.

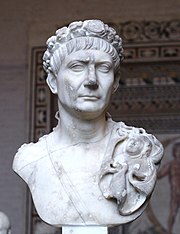

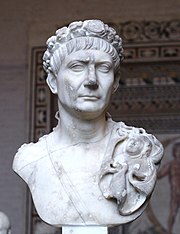

Bust of Trajan,

Glyptothek,

Munich.

It was at this point that Trajan’s health started to fail him. The fortress

city of Hatra, on

the Tigris in

his rear, continued to hold out against repeated Roman assaults. He was

personally present at the

siege and it is

possible that he suffered a heat stroke while in the blazing heat. Shortly

afterwards, the Jews

inside the Eastern Roman Empire rose up in rebellion once more, as did the

people of Mesopotamia. Trajan was forced to withdraw his army in order to put

down the revolts. Trajan saw it as simply a temporary setback, but he was

destined never to command an army in the field again, turning his Eastern armies

over to the high ranking legate and governor of Judaea,

Lusius Quietus, who in early 116 had been in charge of the Roman division

who had recovered Nisibis and

Edessa from the

rebels;

Quietus was promised for this a consulate in the following year – when he was

actually put to death by

Hadrian , who

had no use for a man so committed to Trajan’s aggressive policies.

Early in 117, Trajan grew ill and set out to sail back to Italy. His health

declined throughout the spring and summer of 117, something publicy acknowledged

by the fact that a bronze bust displayed at the time in the public baths of

Ancyra showed him clearly aged and edemaciated.

By the time he had reached Selinus in

Cilicia which

was afterwards called Trajanopolis, he suddenly died from

edema on August

9. Some say that he had adopted

Hadrian as

his successor, but others that it was his wife

Pompeia Plotina who hired someone to impersonate him after he had died.

Hadrian,

upon becoming ruler, recognized the abandonment of Mesopotamia and restored

Armenia – as well as

Osroene – to

the Parthian hegemony under Roman suzerainty

– a telling sign the Roman Empire lacked the means for pursuing Trajan’s

overambitious goals.

However, all the other territories conquered by Trajan were retained. Trajan’s

ashes were laid to rest underneath Trajan’s column, the monument commemorating

his success.

The

Alcántara Bridge, widely hailed as a masterpiece of

Roman engineering.

Eugène Delacroix. The Justice of Trajan (fragment).

Building

activities

Trajan was a prolific builder in Rome and the provinces, and many of his

buildings were erected by the gifted architect

Apollodorus of Damascus. Notable structures include

Trajan’s Column,

Trajan’s Forum,

Trajan’s Bridge,

Alcántara Bridge, and possibly the

Alconétar Bridge. In order to build his forum and the adjacent brick market

that also held his name Trajan had vast areas of the surrounding hillsides

leveled.

Trajan’s

legacy

Unlike many lauded rulers in history, Trajan’s reputation has survived

undiminished for nearly nineteen centuries.

Ancient sources on Trajan’s personality and accomplishments are unanimously

positive. Pliny the younger, for example, celebrates Trajan in his panegyric as

a wise and just emperor and a moral man.

Dio Cassius admits Trajan had vices like heavy drinking and sexual

involvement with boys, but added that he always remained dignified and fair.

The

Christianisation of Rome resulted in further embellishment of his legend: it

was commonly said in

medieval times that

Pope Gregory I, through divine intercession, resurrected Trajan from the

dead and baptized him into the Christian faith. An account of this features in

the

Golden Legend.

Theologians, such as

Thomas Aquinas, discussed Trajan as an example of a virtuous pagan. In

the Divine Comedy,

Dante, following this legend, sees the spirit of Trajan in the Heaven of

Jupiter with other historical and mythological persons noted for their

justice.

He also features in

Piers

Plowman. An episode, referred to as the

justice of Trajan was reflected in several art works.

In the 18th Century King

Charles III of Spain comminsioned

Anton Raphael Mengs to paint The Triumph of Trajan on the ceiling of

the banqueting-hall of the

Royal Palace of Madrid – considered among the best work of this artist.

“Traian” is used as a male first name in present-day

Romania –

among others, that of the country’s incumbent president,

Traian Băsescu.

|

Roman

Roman