|

Trajan

–

Roman Emperor

: 98-117 A.D. –

Silver Denarius 19mm (2.79 grams) Struck circa 98-117 A.D.

Reference: RIC 104

IMP TRAIANO AVG GER DAC P M TR P, laureate bust right, aegis on far shoulder

COS V P P SPQR OPTIMO PRINC, Pietas, veiled, standing left by altar,

holding patera

and sceptre, PIET in ex.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Pietas, translated variously as “duty”, “religiosity” or

“religious behavior”,”loyalty”,”devotion”, or “filial

piety” (English “piety” derives from the Latin), was one of the chief

virtues

among the

ancient Romans

. It was the distinguishing

virtue of the

founding

hero

Aeneas

, who is often given the

adjectival

epithet pius throughout

Vergil

‘s epic

Aeneid

. The sacred nature of pietas

was embodied by the divine personification Pietas, a goddess often pictured on

Roman coins. The Greek equivalent is

eusebeia

.

Cicero

defined pietas as the virtue

“which admonishes us to do our duty to our country or our parents or other blood

relations.” The man who possessed pietas “performed all his duties

towards the deity and his fellow human beings fully and in every respect,” as

the 19th-century classical scholar

Georg Wissowa

described it.

Livia

wife of Augustus as Pietas

As virtue

Pietas erga parentes (“pietas toward one’s parents”) was one of

the most important aspects of demonstrating virtue. Pius as a

cognomen

originated as way to mark a person

as especially “pious” in this sense: announcing one’s personal pietas

through official nomenclature seems to have been an innovation of the

late Republic

, when

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius

claimed it for

his efforts to have his father,

Numidicus

, recalled from exile.

Pietas extended also toward “parents” in the sense of

“ancestors,” and was one of the basic principles of

Roman tradition

, as expressed by the care of

the dead.

Pietas as a virtue resided within a person, in contrast

to a virtue or gift such as

Victoria

, which was given by the gods.

Pietas, however, allowed a person to recognize the divine source of benefits

conferred.

The first recorded use of pietas in English occurs in Anselm Bayly’s

The Alliance of Music, Poetry, and Oratory, published in 1789.

Iconography

Denarius of Herennius, depicting Pietas and an act of pietas.

Pietas was represented on coin by cult objects, but also as a woman

conducting a sacrifice by means of fire at an altar. In the imagery of

sacrifice, libation

was the fundamental act that came to

symbolize pietas.

Pietas is first represented on Roman coins on

denarii

issued by

Marcus Herennius

in 108 or 107 BC. Pietas

appears on the obverse as a divine personification, in

bust

form; the quality of pietas is

represented by a son carrying his father on his back.Pietas is among the virtues

that appear frequently on Imperial coins, including those issued under

Hadrian

.

One of the symbols of pietas was the stork, described by

Petronius

as pietaticultrix, “cultivator

of pietas.” The stork represented filial piety in particular, as the

Romans believed that it demonstrated family loyalty by returning to the same

nest every year, and that it took care of its parents in old age. As such, a

stork appears next to Pietas on

a coin issued by Metellus Pius

(on whose

cognomen see above

).

As goddess

Flavia Maximiana Theodora

on the

obverse, on the reverse Pietas holding infant to her breast.

Pietas was the divine presence in everyday life that cautioned humans not to

intrude on the realm of the gods. Violations of pietas required a

piaculum

, expiatory rites.

A temple to Pietas was vowed (votum)

by

Manius Acilius Glabrio

at the

Battle of Thermopylae in 191 BC

.

According to a miraculous legend (miraculum),

a poor woman who was starving in prison was saved when her daughter gave her

breast milk (compare

Roman Charity

). Caught in the act, the daughter

was not punished, but recognized for her pietasas. Mother and daughter were set free, and given public

support for the rest of their lives. The site was regarded as sacred to the

goddess Pietas (consecratus deae)pietas erga parentes

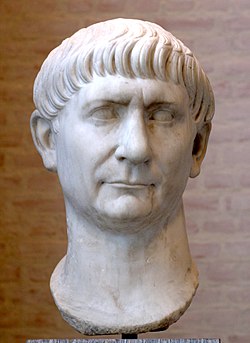

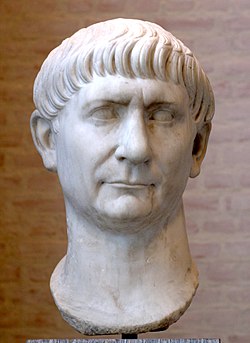

Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus, commonly known as

Trajan (18 September, 53 – 8 August, 117), was a

Roman Roman

Emperor who reigned from AD 98 until his death in AD 117. Born

Marcus Ulpius Traianus into a non-patrician

family in the

Hispania Baetica

province (modern day

Spain

), Trajan rose to prominence during the

reign of emperor

Domitian

, serving as a general in the

Roman army

along the

German frontier

, and successfully crushing the

revolt of

Antonius Saturninus

in 89. On September 18, 96,

Domitian was succeeded by

Marcus Cocceius Nerva

, an old and childless

senator who proved to be unpopular with the army. After a brief and tumultuous

year in power, a revolt by members of the

Praetorian Guard

compelled him to adopt the

more popular Trajan as his heir and successor. Nerva died on January 27, 98, and

was succeeded by his adopted son without incident.

As a civilian administrator, Trajan is best known for his

extensive public building program, which reshaped the city of

Rome and left multiple enduring landmarks such as

Trajan’s Forum

,

Trajan’s Market

and

Trajan’s Column

. It was as a military commander

however that Trajan celebrated his greatest

triumphs

. In 101, he launched a

punitive expedition

into the kingdom of

Dacia

against king

Decebalus

, defeating the Dacian army near

Tapae

in 102, and finally conquering Dacia

completely in 106. In 107, Trajan pushed further east and annexed the

Nabataean kingdom

, establishing the province of

Arabia Petraea

. After a period of relative

peace within the Empire, he launched his final campaign in 113 against

Parthia

, advancing as far as the city of

Susa in 116, and expanding the Roman Empire to its greatest extent.

During this campaign Trajan was struck by illness, and late in 117, while

sailing back to Rome, he died of a

stroke

on

August 9

, in the city of

Selinus

. He was

deified

by the Senate and his ashes were laid

to rest under

Trajan’s Column

. He was succeeded by his

adopted son (not having a biological heir)

Publius Aelius Hadrianus

—commonly known as

Hadrian.

As an emperor, Trajan’s reputation has endured – he is one of

the few rulers whose reputation has survived the scrutiny of nineteen centuries

of history. Every new emperor after him was honoured by the Senate with the

prayer felicior Augusto, melior Traiano, meaning “may he be luckier than

Augustus

and better than Trajan”. Among

medieval

Christian theologians, Trajan was

considered a

virtuous pagan

, while the 18th century

historian

Edward Gibbon

popularized the notion of the

Five Good Emperors

, of which Trajan was the

second.

Early life and rise to power

Trajan was born on September 18, 53 in the Roman province of

Hispania Baetica

(in what is now

Andalusia

in modern Spain), a province that was

thoroughly Romanized and called southern Hispania, in the city of

Italica

, where the

Italian

families were paramount. Of

Italian

stock himself, Trajan is frequently but

misleadingly designated the first provincial emperor.

Trajan was the son of

Marcia

and

Marcus Ulpius Traianus

, a prominent

senator

and general from the famous

Ulpia

gens.

Trajan himself was just one of many well-known Ulpii in a line that continued

long after his own death. His elder sister was

Ulpia Marciana

and his niece was

Salonina Matidia

. The

patria

of the Ulpii was

Italica

, in Spanish Baetica, where their

ancestors had settled late in the third century B.C. This indicates that the

Italian origin was paramount, yet it has recently been cogently argued that the

family’s ancestry was local, with Trajan senior actually a Traius who was

adopted into the family of the Ulpii.

As a young man, he rose through the ranks of the

Roman army

, serving in some of the most

contentious parts of the Empire’s frontier. In 76–77, Trajan’s father was

Governor

of

Syria

(Legatus

pro praetore Syriae), where Trajan himself remained as

Tribunus

legionis. Trajan was nominated as

Consul

and brought

Apollodorus of Damascus

with him to

Rome around 91. Along the

Rhine River

, he took part in the Emperor

Domitian

‘s wars while under Domitian’s

successor, Nerva

, who was unpopular with the army and

needed to do something to gain their support. He accomplished this by naming

Trajan as his adoptive son and successor in the summer of 97. According to the

Augustan History

, it was the future Emperor

Hadrian

who brought word to Trajan of his

adoption. When Nerva died on January 27, 98, the highly respected Trajan

succeeded without incident.

His

reign

The new Roman emperor was greeted by the people of Rome with

great enthusiasm, which he justified by governing well and without the

bloodiness that had marked Domitian’s reign. He freed many people who had been

unjustly imprisoned by Domitian and returned a great deal of private property

that Domitian had confiscated; a process begun by Nerva before his death. His

popularity was such that the

Roman Senate

eventually bestowed upon Trajan

the honorific

of optimus, meaning “the

best”.

Dio Cassius

, sometimes known as Dio, reveals

that Trajan drank heartily and was

involved with boys

. “I know, of course, that he

was devoted to boys and to wine, but if he had ever committed or endured any

base or wicked deed as the result of this, he would have incurred censure; as it

was, however, he drank all the wine he wanted, yet remained sober, and in his

relation with boys he harmed no one.” This sensibility was one that influenced

his governing on at least one occasion, leading him to favour the king of Edessa

out of appreciation for his handsome son: “On this occasion, however,

Abgarus

, induced partly by the persuasions of

his son Arbandes, who was handsome and in the pride of youth and therefore in

favour with Trajan, and partly by his fear of the latter’s presence, he met him

on the road, made his apologies and obtained pardon, for he had a powerful

intercessor in the boy.”

Dacian

Wars

It was as a military commander that Trajan is best known to

history, particularly for his conquests in the

Near East

, but initially for the two wars

against Dacia

— the reduction to client kingdom

(101-102), followed by actual incorporation to the Empire of the trans-Danube

border kingdom of Dacia—an area that had troubled Roman thought for over a

decade with the unfavourable (and to some, shameful) peace negotiated by

Domitian

‘s ministers In the first war c.

March–May 101, he launched a vicious attack into the kingdom of

Dacia

with four legions, crossing to the

northern bank of the

Danube River

on a stone bridge he had built,

and defeating the Dacian army near or in a

mountain pass

called

Tapae

(see

Second Battle of Tapae

). Trajan’s troops were

mauled in the encounter, however and he put off further campaigning for the year

to heal troops, reinforce, and regroup.

During the following winter, King

Decebalus

launched a counter-attack across the

Danube

further downstream, but this was

repulsed. Trajan’s army advanced further into Dacian territory and forced King

Decebalus to submit to him a year later, after Trajan took the Dacian

capital/fortress of

Sarmizegethusa

. The Emperor Domitian had

campaigned against

Dacia from 86 to 87

without securing a decisive

outcome, and Decebalus had brazenly flouted the terms of the peace (89 AD) which

had been agreed on conclusion of this campaign.

Trajan now returned to Rome in triumph and was granted the

title Dacicus Maximus. The victory was celebrated by the

Tropaeum Traiani

. Decebalus though, after being

left to his own devices, in 105 undertook an invasion against Roman territory by

attempting to stir up some of the tribes north of the river against her.

Trajan took to the field again and after building with the

design of

Apollodorus of Damascus

his

massive bridge over the Danube

, he conquered

Dacia completely in 106. Sarmizegethusa was destroyed,

Decebalus

committed

suicide

, and his severed head was exhibited in

Rome on the steps leading up to the

Capitol

. Trajan built a new city, “Colonia

Ulpia Traiana Augusta Dacica Sarmizegetusa”, on another site than the previous

Dacian Capital, although bearing the same full name, Sarmizegetusa. He resettled

Dacia with Romans and annexed it as a province of the Roman Empire. Trajan’s

Dacian campaigns benefited the Empire’s finances through the acquisition of

Dacia’s gold mines. The victory is celebrated by

Trajan’s Column

.

Expansion

in the East

At about the same time

Rabbel II Soter

, one of Rome’s client kings,

died. This event might have prompted the annexation of the

Nabataean kingdom

, although the manner and the

formal reasons for the annexation are unclear. Some epigraphic evidence suggests

a military operation, with forces from

Syria

and

Egypt

. What is clear, however, is that by 107,

Roman legions were stationed in the area around

Petra

and

Bostra

, as is shown by a papyrus found in

Egypt. The empire gained what became the province of

Arabia Petraea

(modern southern

Jordan

and north west

Saudi Arabia

).

Period

of peace

The next seven years, Trajan ruled as a civilian emperor, to

the same acclaim as before. It was during this time that he corresponded with

Pliny the Younger

on the subject of how to deal

with the

Christians

of

Pontus

, telling Pliny to leave them alone

unless they were openly practicing the religion. He built several new buildings,

monuments and roads in

Italia

and his native

Hispania

. His magnificent complex in Rome

raised to commemorate his victories in

Dacia

(and largely financed from that

campaign’s loot)—consisting of a

forum

,

Trajan’s Column

, and Trajan’s Market still

stands in Rome today. He was also

a prolific builder of triumphal arches

, many of

which survive, and rebuilder of roads (Via

Traiana and

Via Traiana Nova

).

One notable act of Trajan was the hosting of a three-month

gladiatorial

festival in the great

Colosseum

in Rome (the precise date of this

festival is unknown). Combining chariot racing, beast fights and close-quarters

gladiatorial bloodshed, this gory spectacle reputedly left 11,000 dead (mostly

slaves and criminals, not to mention the thousands of ferocious beasts killed

alongside them) and attracted a total of five million spectators over the course

of the festival.

Another important act was his formalisation of the

Alimenta, a welfare program that helped orphans and poor children throughout

Italy. It provided general funds, as well as food and subsidized education. The

program was supported initially by funds from the Dacian War, and then later by

a combination of estate taxes and philanthropy.[13].

Although the system is well documented in literary sources and contemporary

epigraphy, its precise aims are controversial and have generated considerable

dispute between modern scholars: usually, it’s assumed that the programme

intended to bolster citzen numbers in Italy. However, the fact that it was

subsidized by means of interest payments on loans made by landowners restricted

it to a small percentage of potential welfare recipients (Paul

Veyne has assumed that, in the city of

Veleia

, only one child out of ten was an actual

beneficiary) – therefore, the idea, advanced by

Moses I. Finley

, that the whole scheme was at

most a form of random charity, a mere imperial benevolence[14].

Maximum

extent of the Empire

The extent of the Roman Empire under Trajan (117)

In 113, he embarked on his last campaign, provoked by

Parthia

‘s decision to put an unacceptable king

on the throne of Armenia

, a kingdom over which the two great

empires had shared

hegemony

since the time of

Nero some fifty years earlier. Some modern historians also attribute

Trajan’s decision to wage war on Parthia to economic motives: to control, after

the annexation of Arabia, Mesopotamia and the coast of the Persian Gulf, and

with it the sole remaining receiving-end of the Indian trade outside Roman

control – an attribution of motive other historians find absurd, as seeing a

commercial motive in a campaign triggered by the lure of territorial annexation

and prestige – by the way, the only motive for Trajan’s actions ascribed by Dio

Cassius in his description of the events. Other modern historians, however,

think that Trajan’s original aim was quite modest: to assure a more defensible

Eastern frontier for the Roman Empire, crossing across Northern Mesopotamia

along the course of the river

Khabur

in order to offer cover to a Roman

Armenia.

Trajan marched first on Armenia, deposed the

Parthian-appointed king (who was afterwards murdered while kept in the custody

of Roman troops in an unclear incident) and annexed it to the Roman Empire as a

province, receiving in passing the acknowledgement of Roman hegemony by various

tribes in the Caucasus and on the Eastern coast of the Black Sea – a process

that kept him busy until the end of 114].

The cronology of subsequent events is uncertain, but it’s generally believed

that early in 115 Trajan turned south into the core Parthian hegemony, taking

the Northern Mesopotamian cities of

Nisibis

and

Batnae

and organizing a province of

Mesopotamia

in the beginning of 116, when coins

were issued announcing that Armenia and Mesopotamia had been put under the

authority of the Roman people.

In early 116, however, Trajan began to toy with the conquest

of the whole of Mesopotamia, an overambitious goal that eventually backfired on

the results of his entire campaign: One Roman division crossed the

Tigris

into

Adiabene

, sweeping South and capturing

Adenystrae

; a second followed the river South,

capturing Babylon

; while Trajan himself sailed down the

Euphrates

, then dragged his fleet overland into

the Tigris, capturing

Seleucia

and finally the Parthian capital of

Ctesiphon

. He continued southward to the

Persian Gulf

, receiving the submission of

Athambelus, the ruler of

Charax

, whence he declared Babylon a new

province of the Empire, sent the Senate a laurelled letter declaring the war to

be at a close and lamented that he was too old to follow in the steps of

Alexander the Great

and reach the distant

India

itself. A province of

Assyria

was also proclaimed, apparently

covering the territory of Adiabene, as well as some measures seem to have been

considered about the fiscal administration of the Indian trade.

However, as Trajan left the Persian Gulf for Babylon – where

he intended to offer sacrifice to Alexander in the house where he had died in

323 B.C.- a sudden outburst of Parthian resistance, led by a nephew of the

Parthian king, Sanatrukes, imperilled Roman positions in Mesopotamia and

Armenia, something Trajan sought to deal with by forsaking direct Roman rule in

Parthia proper, at least partially: later in 116, after defeating a Parthian

army in a battle where Sanatrukes was killed and re-taking Seleucia, he formally

deposed the Parthian king

Osroes I

and put his own puppet ruler

Parthamaspates

on the throne. That done, he

retreated North in order to retain what he could of the new provinces of Armenia

and Mesopotamia.

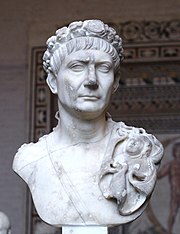

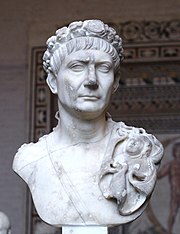

Bust of Trajan,

Glyptothek

,

Munich

.

It was at this point that Trajan’s health started to fail

him. The fortress city of

Hatra

, on the

Tigris

in his rear, continued to hold out

against repeated Roman assaults. He was personally present at the

siege

and it is possible that he suffered a

heat stroke while in the blazing heat. Shortly afterwards, the

Jews inside the Eastern Roman Empire rose up in rebellion once more,

as did the people of Mesopotamia. Trajan was forced to withdraw his army in

order to put down the revolts. Trajan saw it as simply a temporary setback, but

he was destined never to command an army in the field again, turning his Eastern

armies over to the high ranking legate and governor of Judaea,

Lusius Quietus

, who in early 116 had been in

charge of the Roman division who had recovered Nisibis and

Edessa

from the rebels; Quietus was promised

for this a consulate in the following year – when he was actually put to death

by Hadrian

, who had no use for a man so committed

to Trajan’s aggressive policies.

Early in 117, Trajan grew ill and set out to sail back to

Italy. His health declined throughout the spring and summer of 117, something

publicy acknowledged by the fact that a bronze bust displayed at the time in the

public baths of

Ancyra

showed him clearly aged and edemaciated.

By the time he had reached Selinus in

Cilicia

which was afterwards called

Trajanopolis, he suddenly died from

edema

on August 9. Some say that he had adopted

Hadrian

as his successor, but others that it

was his wife

Pompeia Plotina

who hired someone to

impersonate him after he had died.

Hadrian

, upon becoming ruler, recognized the

abandonment of Mesopotamia and restored Armenia – as well as

Osroene

– to the Parthian hegemony under Roman

suzerainty – a telling sign the Roman Empire lacked the means for pursuing

Trajan’s overambitious goals. However, all the other territories conquered by

Trajan were retained. Trajan’s ashes were laid to rest underneath Trajan’s

column, the monument commemorating his success.

The

Alcántara Bridge

, widely hailed as

a masterpiece of

Roman engineering

.

Building

activities

Trajan was a prolific builder in Rome and the provinces, and

many of his buildings were erected by the gifted architect

Apollodorus of Damascus

. Notable structures

include

Trajan’s Column

,

Trajan’s Forum

,

Trajan’s Bridge

,

Alcántara Bridge

, and possibly the

Alconétar Bridge

. In order to build his forum

and the adjacent brick market that also held his name Trajan had vast areas of

the surrounding hillsides leveled.

Trajan’s

legacy

Unlike many lauded rulers in history, Trajan’s reputation has

survived undiminished for nearly nineteen centuries.

Ancient sources on Trajan’s personality and accomplishments

are unanimously positive. Pliny the younger, for example, celebrates Trajan in

his panegyric as a wise and just emperor and a moral man.

Dio Cassius

admits Trajan had vices like heavy

drinking and sexual involvement with boys, but added that he always remained

dignified and fair. The

Christianisation

of Rome resulted in further

embellishment of his legend: it was commonly said in

medieval

times that

Pope Gregory I

, through divine intercession,

resurrected Trajan from the dead and baptized him into the Christian faith. An

account of this features in the

Golden Legend

.

Theologians, such as

Thomas Aquinas

, discussed Trajan as an example

of a virtuous pagan. In

the Divine Comedy

,

Dante

, following this legend, sees the spirit

of Trajan in the Heaven of

Jupiter

with other historical and mythological

persons noted for their justice.

He also features in

Piers Plowman

. An episode, referred to as

the

justice of Trajan

was reflected in several art

works.

In the 18th Century King

Charles III of Spain

comminsioned

Anton Raphael Mengs

to paint The Triumph of

Trajan on the ceiling of the banqueting-hall of the

Royal Palace of Madrid

– considered among the

best work of this artist.

“Traian” is used as a male first name in present-day

Romania

– among others, that of the country’s

incumbent president,

Traian Băsescu

.

The sestertius, or sesterce, (pl. sestertii) was an

ancient Roman

coin. During the

Roman Republic

it was a small,

silver

coin issued only on rare occasions.

During the

Roman Empire

it was a large

brass

coin.

Helmed Roma head right, IIS behind

Dioscuri

riding right, ROMA in linear frame

below. RSC4, C44/7, BMC13.

The name sestertius (originally semis-tertius) means “2 ½”, the

coin’s original value in

asses

, and is a combination of semis

“half” and tertius “third”, that is, “the third half” (0 ½ being the

first half and 1 ½ the second half) or “half the third” (two units

plus half the third unit, or halfway between the second unit and

the third). Parallel constructions exist in

Danish

with halvanden (1 ½),

halvtredje (2 ½) and halvfjerde (3 ½). The form sesterce,

derived from

French

, was once used in preference to the

Latin form, but is now considered old-fashioned.

It is abbreviated as (originally IIS).

Example of a detailed portrait of

Hadrian

117 to 138

History

The sestertius was introduced c. 211 BC as a small

silver

coin valued at one-quarter of a

denarius

(and thus one hundredth of an

aureus

). A silver denarius was supposed to

weigh about 4.5 grams, valued at ten grams, with the silver sestertius valued at

two and one-half grams. In practice, the coins were usually underweight.

When the denarius was retariffed to sixteen asses (due to the gradual

reduction in the size of bronze denominations), the sestertius was accordingly

revalued to four asses, still equal to one quarter of a denarius. It was

produced sporadically, far less often than the denarius, through 44 BC.

Hostilian

under

Trajan Decius

250 AD

In or about 23 BC, with the coinage reform of

Augustus

, the denomination of sestertius was

introduced as the large brass denomination. Augustus tariffed the value of the

sestertius as 1/100 Aureus

. The sestertius was produced as the

largest brass

denomination until the late 3rd century

AD. Most were struck in the mint of

Rome but from AD 64 during the reign of

Nero (AD 54–68) and

Vespasian

(AD 69–79), the mint of

Lyon (Lugdunum), supplemented production. Lyon sestertii can

be recognised by a small globe, or legend stop), beneath the bust.[citation

needed]

The brass sestertius typically weighs in the region of 25 to 28 grammes, is

around 32–34 mm in diameter and about 4 mm thick. The distinction between

bronze

and brass was important to the Romans.

Their name for brass

was

orichalcum

, a word sometimes also spelled

aurichalcum (echoing the word for a gold coin, aureus), meaning

‘gold-copper’, because of its shiny, gold-like appearance when the coins were

newly struck (see, for example

Pliny the Elder

in his Natural History

Book 34.4).

Orichalcum

was considered, by weight, to be

worth about double that of bronze. This is why the half-sestertius, the

dupondius

, was around the same size and weight

as the bronze as, but was worth two asses.

Sestertii continued to be struck until the late 3rd century, although there

was a marked deterioration in the quality of the metal used and the striking

even though portraiture remained strong. Later emperors increasingly relied on

melting down older sestertii, a process which led to the zinc component being

gradually lost as it burned off in the high temperatures needed to melt copper (Zinc

melts at 419 °C, Copper

at 1085 °C). The shortfall was made up

with bronze and even lead. Later sestertii tend to be darker in appearance as a

result and are made from more crudely prepared blanks (see the

Hostilian

coin on this page).

The gradual impact of

inflation

caused by

debasement

of the silver currency meant that

the purchasing power of the sestertius and smaller denominations like the

dupondius and as was steadily reduced. In the 1st century AD, everyday small

change was dominated by the dupondius and as, but in the 2nd century, as

inflation bit, the sestertius became the dominant small change. In the 3rd

century silver coinage contained less and less silver, and more and more copper

or bronze. By the 260s and 270s the main unit was the double-denarius, the

antoninianus

, but by then these small coins

were almost all bronze. Although these coins were theoretically worth eight

sestertii, the average sestertius was worth far more in plain terms of the metal

they contained.

Some of the last sestertii were struck by

Aurelian

(270–275 AD). During the end of its

issue, when sestertii were reduced in size and quality, the

double sestertius

was issued first by

Trajan Decius

(249–251 AD) and later in large

quantity by the ruler of a breakaway regime in the West called

Postumus

(259–268 AD), who often used worn old

sestertii to

overstrike

his image and legends on. The double

sestertius was distinguished from the sestertius by the

radiate crown

worn by the emperor, a device

used to distinguish the dupondius from the as and the antoninianus from the

denarius.

Eventually, the inevitable happened. Many sestertii were withdrawn by the

state and by forgers, to melt down to make the debased antoninianus, which made

inflation worse. In the coinage reforms of the 4th century, the sestertius

played no part and passed into history.

Sestertius of

Hadrian

, dupondius of

Antoninus Pius

, and as of

Marcus Aurelius

As a unit of account

The sestertius was also used as a standard unit of account, represented on

inscriptions with the monogram HS. Large values were recorded in terms of

sestertium milia, thousands of sestertii, with the milia often

omitted and implied. The hyper-wealthy general and politician of the late Roman

Republic,

Crassus

(who fought in the war to defeat

Spartacus

), was said by Pliny the Elder to have

had ‘estates worth 200 million sesterces’.

A loaf of bread cost roughly half a sestertius, and a

sextarius

(~0.5 liter) of

wine anywhere from less than half to more than 1 sestertius. One

modius

(6.67 kg) of

wheat

in 79 AD

Pompeii

cost 7 sestertii, of

rye

3 sestertii, a bucket 2 sestertii, a tunic 15 sestertii, a donkey 500 sestertii.

Records from Pompeii

show a

slave

being sold at auction for 6,252

sestertii. A writing tablet from

Londinium

(Roman

London

), dated to c. 75–125 AD, records the

sale of a Gallic

slave girl called Fortunata for 600

denarii, equal to 2,400 sestertii, to a man called Vegetus. It is difficult to

make any comparisons with modern coinage or prices, but for most of the 1st

century AD the ordinary

legionary

was paid 900 sestertii per annum,

rising to 1,200 under

Domitian

(81-96 AD), the equivalent of 3.3

sestertii per day. Half of this was deducted for living costs, leaving the

soldier (if he was lucky enough actually to get paid) with about 1.65 sestertii

per day.

Perhaps a more useful comparison is a modern salary: in 2010 a private

soldier in the US Army (grade E-2) earned about $20,000 a year.

Numismatic value

A sestertius of

Nero

, struck at

Rome

in 64 AD. The reverse depicts

the emperor on horseback with a companion. The legend reads DECVRSIO,

‘a military exercise’. Diameter 35mm

Sestertii are highly valued by

numismatists

, since their large size gave

caelatores (engravers) a large area in which to produce detailed portraits

and reverse types. The most celebrated are those produced for

Nero (54-68 AD) between the years 64 and 68 AD, created by some of

the most accomplished coin engravers in history. The brutally realistic

portraits of this emperor, and the elegant reverse designs, greatly impressed

and influenced the artists of the

Renaissance

. The series issued by

Hadrian

(117-138 AD), recording his travels

around the Roman Empire, brilliantly depicts the Empire at its height, and

included the first representation on a coin of the figure of

Britannia

; it was revived by

Charles II

, and was a feature of

United Kingdom

coinage until the

2008 redesign

.

Very high quality examples can sell for over a million

dollars

at auction as of 2008, but the coins

were produced in such colossal abundance that millions survive.

|

Roman

Roman