|

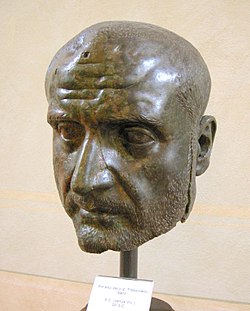

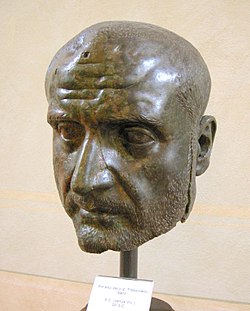

Trebonianus Gallus – Roman Emperor: 251-253 A.D. –

Silver Antoninianus 23mm (3.58 grams) Rome mint: 251-253 A.D.

Reference: RIC 83, C 47

IMPCCVIBTREBGALLVSPFAVG – Radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right.

IVNOMARTIALIS – Juno seated left, holding grain ears and scepter.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

Juno is an

ancient Roman goddess

, the protector and

special counselor of the state. She is a daughter of

Saturn

and sister (but also the wife) of the

chief god

Jupiter

and the mother of

Mars

and

Vulcan

. Juno also looked after the women of

Rome. Her Greek equivalent is

Hera, her Etruscan counterpart is

Uni

. As the

patron goddess

of

Rome and the

Roman Empire

, Juno was called Regina (“queen”)

and, together with Jupiter and

Minerva

, was worshipped as a triad on the

Capitol (Juno Capitolina) in Rome.

Juno’s own warlike aspect among the Romans is apparent in her attire. She

often appeared sitting pictured with a peacock armed and wearing a goatskin

cloak. The traditional depiction of this warlike aspect was assimilated from the

Greek goddess Hera

, whose goatskin was called the ‘aegis’.

Etymology

The name Iuno was also once thought to be connected to Iove

(Jove), originally as Diuno and Diove from *Diovona. At the

beginning of the 20th century, a derivation was proposed from iuven- (as

in Latin iuvenis, “youth”), through a syncopated form iūn- (as in

iūnix, “heifer”, and iūnior, “younger”). This etymology became

widely accepted after it was endorsed by

Georg Wissowa

.

Iuuen- is related to Latin aevum and Greek

aion (αιών) through a common

Indo-European root

referring to a concept of

vital energy or “fertile time”. The iuvenis is he who has the fullness of

vital force. In some inscriptions Jupiter himself is called Iuuntus, and

one of the epithets of Jupiter is Ioviste, a

superlative form

of iuuen- meaning “the

youngest”.

Iuventas

, “Youth”, was one of two deities who

“refused” to leave the

Capitol

when the building of the new

Temple of Capitoline Jove

required the

exauguration

of deities who already occupied

the site.

Ancient etymologies associated Juno’s name with iuvare, “to aid,

benefit”, and iuvenescendo, “rejuvenate”, sometimes connecting it to the

renewal of the new and waxing moon, perhaps implying the idea of a moon goddess.

Roles and epithets

Juno’s theology is one of the most complex and disputed issues in Roman

religion. Even more than other major Roman deities, Juno held a large number of

significant and diverse

epithets

, names and titles representing various

aspects and roles of the goddess. In accordance with her central role as a

goddess of marriage, these included Pronuba and Cinxia (“she who

looses the bride’s girdle”). However, other epithets of Juno have wider

implications and are less thematically linked.

While her connection with the idea of vital force, fulness of vital energy,

eternal youthfulness is now generally acknowledged, the multiplicity and

complexity of her personality have given rise to various and sometimes

irreconcilable interpretations among modern scholars.

Juno is certainly the divine protectress of the community, who shows both a

sovereign and a fertility character, often associated with a military one. She

was present in many towns of ancient Italy: at

Lanuvium

as Sespeis Mater Regina,

Laurentum

,

Tibur

,

Falerii

,

Veii as Regina, at Tibur and Falerii as Regina and Curitis,

Tusculum

and

Norba

as Lucina. She is also attested at

Praeneste

,

Aricia

,

Ardea

,

Gabii

. In five Latin towns a month was named

after Juno (Aricia, Lanuvium, Laurentum, Praeneste, Tibur). Outside Latium in

Campania

at

Teanum

she was Populona (she who increase the

number of the people or, in K. Latte’s understanding of the iuvenes, the

army), in Umbria

at

Pisaurum

Lucina, at Terventum in

Samnium

Regina, at Pisarum Regina Matrona, at

Aesernia

in Samnium Regina Populona. In Rome

she was since the most ancient times named Lucina, Mater and Regina. It is

debated whether she was also known as Curitis before the

evocatio

of the Juno of Falerii: this though

seems probable.

Other epithets of hers that were in use at Rome include Moneta and Caprotina,

Tutula, Fluonia or Fluviona, Februalis, the last ones associated with the rites

of purification and fertility of February.

Her various epithets thus show a complex of mutually interrelated functions

that in the view of

G. Dumezil

and Vsevolod Basanoff (author of

Les dieux Romains) can be traced back to the Indoeuropean trifunctional

ideology: as Regina and Moneta she is a sovereign deity, as Sespeis, Curitis

(spear holder) and Moneta (again) she is an armed protectress, as Mater and

Curitis (again) she is a goddess of the fertility and wealth of the community in

her association with the

curiae

.

The epithet Lucina is particularly revealing since it reflects two

interrelated aspects of the function of Juno: cyclical renewal of time in the

waning and waxing of the moon and protection of delivery and birth (as she who

brings to light the newborn as vigour, vital force). The ancient called her

Covella in her function of helper in the labours of the new moon. The

view that she was also a Moon goddess though is no longer accepted by scholars,

as such a role belongs to

Diana

Lucifera: through her association

with the moon she governed the feminine physiological functions, menstrual cycle

and pregnancy: as a rule all lunar deities are deities of childbirth. These

aspects of Juno mark the heavenly and worldly sides of her function. She is thus

associated to all beginnings and hers are the

kalendae

of every month: at Laurentum she was

known as Kalendaris Iuno (Juno of the

Kalends

). At Rome on the Kalends of every month

the

pontifex

minor invoked her, under the

epithet Covella, when from the curia Calabra announced the date of

the nonae. On the same day the

regina sacrorum

sacrificed to Juno a white

sow or lamb in the Regia

. She is closely associated with

Janus

, the god of passages and beginnings who

after her is often named Iunonius.

Some scholars view this concentration of multiple functions as a typical and

structural feature of the goddess, inherent to her being an expression of the

nature of femininity. Others though prefer to dismiss her aspects of femininity

and fertility and stress only her quality of being the spirit of youthfulness,

liveliness and strength, regardless of sexual connexions, which would then

change according to circumstances: thus in men she incarnates the iuvenes,

word often used to design soldiers, hence resulting in a tutelary deity of the

sovereignty of peoples; in women capable of bearing children, from puberty on

she oversees childbirth and marriage. Thence she would be a poliad

goddess related to politics, power and war. Other think her military and

poliadic qualities arise from her being a fertility goddess who through her

function of increasing the numbers of the community became also associated to

political and military functions.

Juno Sospita and

Lucina

Part of the following sections is based on the article by Geneviève Dury

Moyaers and Marcel Renard “Aperçu critique des travaux relatifs au culte de

Junon” in Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römische Welt 1981 p. 142-202.

The rites of the month of February and the Nonae Caprotinae of July 5

offer a depiction of the interrelated roles of the deity in the spheres of

fertility, war, and regality.

February is a month of passages, of ends and beginnings, and as such the

month of yearly universal purification and renewal. Ovid discusses the etymology

of February at the beginning of book II of the Fasti, connecting it to

februae, i.e. piamina, expiations. As the most important time of

passage of the year it implies risks for the community that have to be averted:

the risk of contamination brought about by the contact with the underworld. Juno

is then present and active at the three most prominent and relevant times of the

month: on the kalendae (the first), with the celebration of the

dies natalis

(“birthday”) of Juno Sospita

on the Palatine

, on 15th as Juno Lucina, inspirator

and patroness of the

Lupercalia

and as Lucina and at its end, on

March 1, as the protectress of the Matronae and of the preservation of

marriages: this day united into one three festivals as it was the kalendae

of the month, the beginning of the new year and the birthday of Romulus (as well

as the date of the commemoration of the appeasing role of women during the war

between Romans and Sabines).

Juno as Sospita (the Saviour) is thus the goddess that defends and protects

the Romans since the first day in this perilous time of passage. On the same day

recurred the celebration at the lucus grove of

Helernus

, which Dumezil thinks was a

god of vegetation

related to the cult of

Carna

/Crane, a nymph who may be an image of

Juno Sospita. The way this period should be dealt with came to a concrete

acme on the 15 in the

Lupercalia

: the rite was directly suggested to

the Roman couples by Juno Lucina in her lucus on the

Esquiline

, and was considered to be a rite of

periodical purification and fertility. It was perhaps also associated to the

renewal of political power, as it may appear in the competition between the two

groups of the

Luperci

, the Fabii and the Quinctii, mythically

associated to Remus and Romulus. This political valence is illustrated by the

episode of

Julius Caesar

who chose this occasion to enact

the scene of his crowning by

Mark Antony

and by the fact that he created a

third group, the Luperci Iulii. This element would perhaps be the reason of the

eulogy of Augustus at the beginning of book II of Ovid’s Fasti: as the

heir of Caesar he had indeed succeeded in his stepfather’s plan. Here is then

the sovereign function of Juno that is highlighted.

After Wissowa many scholars have remarked the similarity between the Juno of

the Lupercalia and the Juno of Lanuvium Seispes Mater Regina as both are

associated with the goat, symbol of fertility. But in essence there is unity

between fertility, regality and purification. This unity is underlined by the

role of Faunus

in the aetiologic story told by Ovid and

the symbolic relevance of the

Lupercal

: asked by the Roman couples at her

lucus how to overcome the sterility that ensued the abduction of the Sabine

women, Juno answered through a murmuring of leaves “Italidas matres sacer

hircus inito” “That a sacred ram cover the Italic mothers”.

February owes its name to the februae, lustrations, and the goat whose

hide is used to make the whips of the

Luperci

is named februum and amiculus

Iunonis. The Juno of this day bears the epithet of Februalis,

Februata, Februa.[30]

Februlis oversees the secundament of the placenta and is strictly

associated to Fluvonia, Fluonia, goddess who retains the blood inside the

body during pregnancy. While the protection of pregnancy is stressed by Duval,

Palmer sees in Fluonia only the Juno of lustration in river water. Ovid devotes

an excursus to the lustrative function of river water in the same place

in which he explains the etymology of February.

A temple (aedes) of Juno Lucina was built in 375 BC in the grove

sacred to the goddess from early times. It stood precisely on the

Cispius

near the sixth shrine of the

Argei

. probably not far west of the church of

S. Prassede, where inscriptions relating to her cult have been found. The grove

should have extended down the slope south of the temple. As

Servius Tullius

ordered the gifts for the

newborn to be placed in the treasury of the temple though it looks that another

shrine stood there before 375 BC. In 190 BC the temple was struck by lightning,

its gable and doors injured. The annual festival of the

Matronalia

was celebrated here on March 1, day

of the dedication of the temple.

A temple to Iuno Sospita was vowed by consul C. Cornelius Cethegus in 197 BC

and dedicated in 194. By 90 BC the temple had fallen into disrepute: in that

year it was stained by episodes of prostitution and a bitch delivered her

puppies right beneath the statue of the goddess. By decree of the senate consul

L. Iulius Caesar

ordered its restoration. In

his poem Fasti Ovid states the temple of Juno Sospita had become

dilapidated to the extent of being no longer discernible “because of the

injuries of time”: this looks hardly possible as the restoration had happened no

longer than a century earlier and relics of the temple exixst to-day. It is

thence plausible that an older temple of Juno Sospita existed in Rome within the

pomerium

, as Ovid says it was located near the

temple of the Phrygian Mother (Cybele),

which stood on the western corner of the

Palatine

. As a rule temples of foreign,

imported gods stood without the pomerium.

Juno Caprotina

The alliance of the three aspects of Juno finds a strictly related parallel

to the Lupercalia in the festival of the Nonae Caprotinae. On that day

the Roman free and slave women picniced and had fun together near the site of

the wild fig (caprificus): the custom implied runs, mock battles with

fists and stones, obscene language and finally the sacrifice of a male goat to

Juno Caprotina under a wildfig tree and with the using of its lymph.

This festival had a legendary aetiology in a particularly delicate episode of

Roman history and also recurs at (or shortly after) a particular time of the

year, that of the so-called caprificatio when branches of wild fig trees

were fastened to cultivated ones to promote insemination. The historical episode

narrated by ancient sources concerns the siege of Rome by the Latin peoples that

ensued the Gallic sack. The dictator of the Latins Livius Postumius from

Fidenae

would have requested the Roman senate

that the matronae and daughters of the most prominent families be

surrendered to the Latins as hostages. While the senate was debating the issue a

slave girl, whose Greek name was

Philotis

and Latin Tutela or Tutula proposed

that she together with other slave girls would render herself up to the enemy

camp pretending to be the wives and daughters of the Roman families. Upon

agreement of the senate, the women dressed up elegantly and wearing golden

jewellery reached the Latin camp. There they seduced the Latins into fooling and

drinking: after they had fallen asleep they stole their swords. Then Tutela gave

the convened signal to the Romans brandishing an ignited branch after climbing

on the wild fig (caprificus) and hiding the fire with her mantle. The

Romans then irrupted into the Latin camp killing the enemies in their sleep. The

women were rewarded with freedom and a dowry at public expenses.

Dumezil in his Archaic Roman Religion had been unable to interpret the

myth underlying this legendary event, later though he accepted the

interpretation given by P. Drossart and published it in his Fêtes romaines

d’été et d’automne, suivi par dix questions romaines in 1975 as Question

IX. In folklore the wild fig tree is universally associated with sex because

of its fertilising power, the shape of its fruits and the white viscous juice of

the tree.

Basanoff has argued that the legend not only alludes to sex and fertility in

its association with wildfig and goat but is in fact a summary of sort of all

the qualities of Juno. As Juno Sespeis of Lanuvium Juno Caprotina is a warrior,

a fertiliser and a sovereign protectress. In fact the legend presents a heroine,

Tutela, who is a slightly disguised representation of the goddess: the request

of the Latin dictator would mask an attempted

evocatio

of the tutelary goddess of Rome.

Tutela indeed shows regal, military and protective traits, apart from the sexual

ones. Moreover according to Basanoff these too (breasts, milky juice,

genitalia, present or symbolised in the fig and the goat) in general, and

here in particular, have an inherently apotropaic value directly related to the

nature of Juno. The occasion of the feria, shortly after the

poplifugia

, i.e. when the community is in its

direst straits, needs the intervention of a divine tutelary goddess, a divine

queen, since the king (divine or human) has failed to appear or has fled. Hence

the customary battles under the wild figs, the scurrile language that bring

together the second and third function. This festival would thus show a ritual

that can prove the trifunctional nature of Juno.

Other scholars limit their interpretation of Caprotina to the sexual

implications of the goat, the caprificus and the obscene words and plays

of the festival.

Juno Curitis

Under this epithet Juno is attested in many places, notably at

Falerii

and

Tibur

. Dumezil remarked that Juno Curitis “is

represented and invoked at Rome under conditions very close to those we know

about for Juno Seispes of

Lanuvium

“. Martianus Capella states she must be

invoked by those who are involved in war. The hunt of the goat by stonethrowing

at Falerii is described in Ovid Amores III 13, 16 ff. In fact the Juno

Curritis of Falerii shows a complex articulated structure closely allied to the

threefold Juno Seispes of Lanuvium.

Ancient etymologies associated the epithet with

Cures

, with the Sabine word for spear curis,

with currus cart, with Quirites, with the curiae, as king

Titus Tatius dedicated a table to Juno in every curia, that Dionysius still saw.

Modern scholars have proposed the town of Currium or Curria,

Quirinus

, *quir(i)s or *quiru,

the Sabine word for spear and

curia

. The *quiru- would design the sacred

spear that gave the name to the primitive curiae. The discovery at

Sulmona

of a sanctuary of

Hercules

Curinus lends support to a

Sabine origin of the epithet and of the cult of Juno in the curiae. The spear

could also be the celibataris hasta (bridal spear) that in the marriage

ceremonies was used to comb the bridegroom’s hair as a good omen. Palmer views

the rituals of the curiae devoted to her as a reminiscence of the origin of the

curiae themselves in rites of evocatio, practise the Romans continued to

use for Juno or her equivalent at later times as for Falerii,

Veii and

Carthage

. Juno Curitis would then be the evoked

deity after her admission into the curiae.

Juno Curitis had a temple on the

Campus Martius

. Excavations in Largo di Torre

Argentina have revealed four temple structures, one of whom (temple D or A)

could be the temple of Juno Curitis. She shared her anniversary day with

Juppiter Fulgur, who had an altar nearby.

Juno Moneta

This Juno is placed by ancient sources in a warring context. Dumezil thinks

the third, military, aspect of Juno is reflected in Juno Curitis and Moneta.

Palmer too sees in her a military aspect

As for the etymology Cicero gives the verb monēre warn, hence the

Warner. Palmer accepts Cicero’s etymology as a possibility while adding

mons mount, hill, verb e-mineo and noun monile referred to the

Capitol, place of her cult. Also perhaps a cultic term or even, as in her temple

were kept the

Libri Lintei

, monere would thence

have the meaning of recording:

Livius Andronicus

identifies her as

Mnemosyne

.

Her dies natalis was on the kalendae of June. Her Temple on the summit

of the Capitol was dedicted only in 348 BC by dictator L. Furius Camillus,

presumably a son of the great Furius. Livy states he vowed the temple during a

war against the Aurunci

. Modern scholars agree that the origins

of the cult and of the temple were much more ancient. M. Guarducci considers her

cult very ancient, identifying her with Mnemosyne as the Warner because

of her presence near the

auguraculum

, her oracular character, her

announcement of perils: she considers her as an introduction into Rome of the

Hera of

Cuma

dating to the 8th century. L. A. Mac Kay

considers the goddess more ancient than her etymology on the testimony of

Valerius Maximus

who states she was the Juno of

Veii. The sacred geese of the Capitol were lodged in her temple: as they are

recorded in the episode of the Gallic siege (ca. 396-390 BC) by Livy, the temple

should have existed before Furius’s dedication. Basanoff considers her to go

back to the regal period: she would be the Sabine Juno who arrived at Rome

through Cures

. At Cures she was the tutelary deity of

the military chief: as such she is never to be found among Latins. This new

quality is apparent in the location of her fanum, her name, her role: 1.

her altar is located in the regia of Titus Tatius; 2. Moneta is, from monere,

the Adviser: like

Egeria

with Numa (Tatius’s son in law) she is

associated to a Sabine king; 3. In

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

the altar-tables of

the curiae are consecrated to Juno Curitis to justify the false etymology of

Curitis from curiae: the tables would assure the presence of the tutelary

numen of the king as an adviser within each curia, as the epithet itself

implies. It can be assumed thence that Juno Moneta intervenes under warlike

circumstances as associated to the sacral power of the king.

Juno Regina

Juno Regina is perhaps the epithet most fraught with questions. While some

scholars maintain she was known as such at Rome since the most ancient times as

paredra of Jupiter in the

Capitoline Triad

[71]

others think she is a new acquisition introduced to Rome after her

evocatio

from Veii.

Palmer thinks she is to be identified with Juno Populona of later

inscriptions, a political and military poliadic deity who had in fact a place in

the Capitoline temple and was intended to represent the Regina of the

king. The date of her introduction, though ancient, would be uncertain; she

should perhaps be identified with

Hera Basilea or as the queen of Jupiter Rex. The actual epithet

Regina could though come from Veii. At Rome this epithet may have been applied

to a Juno other than that of the temple on the Aventine built to lodge the

evocated Veian Juno as the

rex sacrorum

and his wife-queen were to offer a

monthly sacrifice to Juno in the Regia. This might imply that the prerepublican

Juno was royal.

IVNO REGINA (“Queen Juno”) on a coin celebrating

Julia Soaemias

.

J. Gagé dismisses these assumptions as groundless speculations as no Jupiter

Rex is attested and in accord with Roe D’Albret stresses that at Rome no

presence of a Juno Regina is mentioned before

Marcus Furius Camillus

, while she is attested

in many Etruscan and Latin towns. Before that time her Roman equivalent was Juno

Moneta. Marcel Renard for his part considers her an ancient Roman figure since

the title of the Veian Juno expresses a cultic reality that is close to and

indeed presupposes the existence at Rome of an analogous character: as a rule it

is the presence of an original local figure that may allow the introduction of

the new one through evocatio. He agrees with Dumezil that we ignore whether the

translation of the epithet is exhaustive and what Etruscan notion corresponded

to the name Regina which itself is certainly an Italic title. This is the

only instance of evocatio recorded by the annalistic tradition. However Renard

considers Macrobius’s authority reliable in his long list of evocationes

on the grounds of an archaeological find at

Isaura

. Roe D’Albret underlines the role played

by Camillus and sees a personal link between the deity and her magistrate.

Similarly Dumezil has remarked the link of Camillus with

Mater Matuta

. In his relationship to the

goddess he takes the place of the king of Veii. Camillus’s devotion to female

deities Mater Matuta and Fortuna and his contemporary vow of a new temple to

both Matuta and Iuno Regina hint to a degree of identity between them: this

assumption has by chance been supported by the discovery at

Pyrgi

of a bronze lamella which mentions

together

Uni

and

Thesan

, the Etruscan Juno and Aurora, i.e.

Mater Matuta. One can then suppose Camillus’s simultaneous vow of the temples of

the two goddesses should be seen in the light of their intrinsic association.

Octavianus

will repeat the same translation

with the statue of the Juno of

Perusia

in consequence of a dream

The fact that a goddess evoked in war and for political reasons receive the

homage of women and that women continue to have a role in her cult is explained

by Palmer as a foreign cult of feminine sexuality of Etruscan derivation. The

persistence of a female presence in her cult through the centuries down to the

lectisternium

of 217 BC, when the matronae

collected money for the service, and to the times of Augustus during the

ludi saeculares

in the sacrifices to Capitoline

Juno are proof of the resilience of this foreign tradition.

Gagé and D’Albret remark an accentuation of the matronal aspect of Juno

Regina that led her to be the most matronal of the Roman goddesses by the time

of the end of the republic. This fact raises the question of understanding why

she was able of attracting the devotion of the matronae. Gagé traces back

the phenomenon to the nature of the cult rendered to the Juno Regina of the

Aventine in which Camillus played a role in person. The original devotion of the

matronae was directed to

Fortuna

. Camillus was devout to her and to

Matuta, both matronal deities. When he brought Juno Regina from Veii the Roman

women were already acquainted with many Junos, while the ancient rites of

Fortuna were falling off. Camillus would have then have made a political use of

the cult of Juno Regina to subdue the social conflicts of his times by

attributing to her the role of primordial mother.

Juno Regina had two temples (aedes) in Rome. The one dedicated by

Furius Camillus in 392 BC stood on the

Aventine

: it lodged the wooden statue of the

Juno transvected from Veii. It is mentioned several times by Livy in connexion

with sacrifices offered in atonement of prodigia. It was restored by Augustus.

Two inscriptions found near the church of S. Sabina indicate the approximate

site of the temple, which corresponds with its place in the lustral procession

of 207 BC, near the upper end of the Clivus Publicius. The day of the dedication

and of her festival was September 1.

Another temple stood near the

circus Flaminius

, vowed by consul

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

in 187 BC during the

war against the Ligures

and dedicated by himself as censor in

179 on December 23. It was connected by a porch with a temple of Fortuna perhaps

that of Fortuna

Equestris. Its probable site according

to Platner is just south of the

porticus Pompeiana

on the west end of circus

Flaminius.

The Juno Cealestis of Carthage

Tanit

was

evoked

according to Macrobius. She did not

receive a temple in Rome: presumably her image was deposited in another temple

of Juno (Moneta or Regina) and later transferred to the

Colonia Junonia

founded by

Caius Gracchus

. The goddess was once again

transferred to Rome by emperor

Elagabalus

.

Juno in the

Capitoline triad

The first mention of a Capitoline triad refers to the Capitolium Vetus.

The only ancient source who refers to the presence of this divine triad in

Greece is

Pausanias

X 5, 1-2, who mentions its existence

in describing the Φωκικόν in

Phocis

. The Capitoline triad poses difficult

interpretative problems. It looks peculiarly Roman, since there is no sure

document of its existence elsewhere either in Latium or Etruria. A direct Greek

influence is possible but it would be also plausible to consider it a local

creation.Dumézil advanced the hypothesis it could be an ideological construction

of the Tarquins to oppose new Latin nationalism, as it included the three gods

that in the Iliad are enemies of

Troy. It is probable Latins had already accepted the legend of Aeneas

as their ancestor. Among ancient sources indeed Servius states that according to

the

Etrusca Disciplina

towns should have the three

temples of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva at the end of three roads leading to three

gates. Vitruvius

writes that the temples of these

three gods should be located on the most elevated site, isolated from the other.

To his Etruscan founders the meaning of this triad might have been related to

peculiarly Etruscan ideas on the association of the three gods with the birth of

Herakles

and the siege of Troy, in which

Minerva

plays a decisive role as a goddess of

destiny along with the sovereign couple Uni Tinia.

The Junos of Latium

The cults of the Italic Junos reflected remarkable theological complexes:

regality, military protection and fertility.

In Latium are relatively well known the instances of Tibur, Falerii,

Laurentum and Lanuvium.

At Tibur and Falerii their sacerdos was a male, called pontifex

sacrarius, fact that has been seen as a proof of the relevance of the

goddess to the whole society. In both towns she was known as Curitis, the

spearholder, an armed protectress. The martial aspect of these Junos is

conspicuous, quite as that of fecundity and regality: the first two look

strictly interconnected: fertility guaranteed the survival of the community,

peaceful and armed. Iuno Curitis is also the tutelary goddess of the curiae

and of the new brides, whose hair was combed with the spear called

caelibataris hasta as in Rome. In her annaual rites at Falerii youths and

maiden clad in white bore in procession gifts to the goddess whose image was

escorted by her priestesses. The idea of purity and virginity is stressed in

Ovid’s description. A she goat is sacrificed to her after a ritual hunting. She

is then the patroness of the young soldiers and of brides.

At Lanuvium the goddess is known under the epithet Seispes Mater Regina. The

titles themselves are a theological definition: she was a sovereign goddess, a

martial goddess and a fertility goddess. Hence her

flamen

was chosen by the highest local

magistrate, the dictator, and since 388 BC the Roman consuls were required to

offer sacrifices to her. Her sanctuary was famous, rich and powerful.

Her cult included the annual feeding of a sacred snake with barley cakes by

virgin maidens. The snake dwelt in a deep cave within the precinct of the

temple, on the arx of the city: the maidens approached the lair

blindfolded. The snake was supposed to feed only on the cakes offered by chaste

girls. The rite was aimed at ensuring agricultural fertility. The site of the

temple as well as the presence of the snake show she was the tutelary goddess of

the city, as Athena at Athens and Hera at Argos. The motive of the snake of the

palace goddess guardian of the city is shared by Iuno Seispes with Athena, as

well as its periodic feeding. This religious pattern moreover includes armour,

goatskin dress, sacred birds and a concern with virginity in cult. Virginity is

connected to regality: the existence and welfare of the community was protected

by virgin goddesses or the virgin attendants of a goddess. This theme shows a

connexion with the fundamental theological character of Iuno, that of

incarnating vital force: virginity is the condition of unspoilt, unspent vital

energy that can ensure communion with nature and its rhythm, symbolised in the

fire of

Vesta

. It is a decisive factor in ensuring the

safety of the community and the growth of crops. The role of Iuno is at the

crossing point of civil and natural life, expressing their interdependence.

At Laurentum

she was known as Kalendaris Iuno and

was honoured as such ritually at the kalendae of each month from March to

December, i.e. the months of the prenuman ten month year, fact which is a

testimony to the antiquity of the custom.

A Greek influence in their cults looks probable. It is noteworthy though that

Cicero remarked the existence of a stark difference between the Latin Iuno

Seispes and the Argolic Hera (as well the Roman Iuno) in his work

De natura deorum

. Claudius Helianus later wrote

“…she has much new of Hera Argolis” The iconogrphy of Argive Hera, matronal

and regal, looks quite far away from the warlike and savage character of Iuno

Seispes, especially considering that it is uncertain whether the former was an

armed Hera.

After the definitive subjugation of the

Latin League

in 338 BC the Romans required as a

condition of peace the condominium of the Roman people on the sanctuary and the

sacred grove of Juno Seispes in Lanuvium, while bestowing Roman citizenry on the

Lanuvins. Consequently the prodigia (supernatural or unearthly phenomena)

happened in her temple were referred to Rome and accordingly expiated there.

Many occurred during the presence of

Hannibal

in Italy. At the time of

Cicero

Milo

, Lanuvium’s dictator and highest

magistrate, resided in Rome. When he met

Clodius

near

Bovillae

and his slaves murdered the

politician, he was on his way to Lanuvium in order to nominate the flamen of

Juno Seispes. Perhaps the Romans were not completely satisfied of this solution

as in 194 BC consul

C. Cornelius Cethegus

erected a temple to the

Juno Sospita of Lanuvium in the Forum Holitorium (vowed three years

earlier in a war with the

Galli Insubri

): in it the goddess was honoured

in martial effigy.

Theological and comparative remarks

The complexity of the figure of Juno has caused much uncertainty and debate

among modern scholars. Some emphasize one aspect or character of the goddess,

considering it as primary: the other ones would then be the natural and even

necessary development of the first. Palmer and Harmon consider it to be the

natural vital force of youthfulness, Latte women’s fecundity. These original

characters would have led to the formation of the complex theology of Juno as a

sovereign and an armed tutelary deity.

Juno. Silver statuette, 1st–2nd century.

G. Dumezil has on the other hand proposed the theory of the irreducibility

and interdependence of the three aspects (sovereignty, war, fertility) that he

interprets as an original, irreducible structure as hypothesised in his theory

of the trifunctional ideology of the Indoeuropean. While Dumezil’s refusal of

seeing a Greek influence in Italic Junos looks difficult to maintain in the

light of the contributions of archaeology, his comparative analysis of the

divine structure is supported by many scholars, as M. Renard and J. Poucet. His

theory purports that while male gods incarnated one single function, there are

female goddesses who make up a synthesis of the three functions, as a reflection

of the ideal of woman’s role in society. Even though such a deity has a peculiar

affinity for one function, generally fertility, i. e. the third, she is

nevertheless equally competent in each of the three.

As concrete instances Dumezil makes that of Vedic goddess

Sarasvatī

and Avestic

Anāhīta

. Sarasvati as river goddess is first a

goddess of the third function, of vitality and fertility associated to the

deities of the third function as the

Aśvin

and of propagation as

Sinīvalī

. She is the mother and on her

rely all vital forces. But at the same time she belongs to the first function as

a religious sovereign: she is pure, she is the means of purifications and helps

the conceiving and realisation of pious thoughts. Lastly she is also a warrior:

allied with the Maruts

she annihilates the enemies and, sole

among female goddesses, bears the epithet of the warrior god

Indra

,

vṛtraghnỉ

, destroyer of oppositions. She

is the common spouse of all the heroes of the

Mahābhārata

, sons and heirs of the Vedic gods

Dharma

,

Vāyu

,

Indra

and of the Aśvin twins. Though in hymns

and rites her threefold nature is never expressed conjointly (except in Ṛg Veda

VI 61, 12:: triṣadásthā having three seats).

Only in her Avestic equivalent Anahita, the great mythic river, does she bear

the same three valences explicitly: her

Yašt

states she is invoked by warriors, by

clerics and by deliverers. She bestows on females an easy delivery and timely

milking. She bestowed on heroes the vigour by which they defeated their demonic

adversaries. She is the great purifier, “she who puts the worshipper in the

ritual, pure condition” (yaož dā). Her complete name too is threefold:

The Wet (Arədvī), The Strong (Sūrā), The Immaculate (Anāhitā).

Dumezil remarks these titles match perfectly those of Latin Junos, especially

the Juno Seispes Mater Regina of Lanuvium, the only difference being in the

religious orientation of the first function. Compare also the epithet Fluonia,

Fluviona of Roman Juno, discussed by G. Radke.However D. P. Harmon has remarked

that the meaning of Seispes cannot be seen as limited to the warrior aspect, as

it implies a more complex, comprehensive function, i. e. of Saviour.

Among Germanic peoples the homologous goddess was bivalent, as a rule the

military function was subsumed into the sovereign: goddess *Frīy(y)o- was at the

same time sovereign, wife of the great god, and Venus (thence *Friy(y)a-dagaz “Freitag

for Veneris dies). However the internal tension of the character led to a

duplication in Scandinavian religion:

Frigg

resulted into a merely sovereign goddess,

the spouse of wizard god

Óðinn

, while from the name of

Freyr

, typical god of the third function, was

extracted a second character,

Freyja

, confined as a

Vani to the sphere of pleasure and wealth.

Dumezil opines that the theologies of ancient Latium could have preserved a

composite image of the goddess and this fact, notably her feature of being

Regina, would in turn have rendered possible her interpretatio as

Hera.

Associations

with other deities

Juno and Jupiter

Jupiter

and Juno, by

Annibale Carracci

.

The divine couple received from Greece its matrimonial implications, thence

bestowing on Juno the role of tutelary goddess of marriage (Iuno Pronuba).

The couple itself though cannot be reduced to a Greek apport. The association

of Juno and Jupiter is of the most ancient Latin theology.

Praeneste

offers a glimpse into original Latin

mythology: the local goddess

Fortuna

is represented as milking two infants,

one male and one female, namely

Jove

(Jupiter) and Juno. It seems fairly safe

to assume that from the earliest times they were identified by their own proper

names and since they got them they were never changed through the course of

history: they were called Jupiter and Juno. These gods were the most ancient

deities of every Latin town. Praeneste preserved divine filiation and infancy as

the sovereign god and his paredra Juno have a mother who is the primordial

goddess Fortuna Primigenia. Many terracotta statuettes have been discovered

which represent a woman with a child: one of them represents exactly the scene

described by Cicero of a woman with two children of different sex who touch her

breast. Two of the votive inscriptions to Fortuna associate her and Jupiter: ”

Fortunae Iovi puero…” and “Fortunae Iovis puero…”

However in 1882 R. Mowat published an inscription in which Fortuna is called

daughter of Jupiter, raising new questions and opening new perspectives

in the theology of Latin gods. Dumezil has elaborated an interpretative theory

according to which this aporia would be an intrinsic, fundamental feature

of Indoeuropean deities of the primordial and sovereign level, as it finds a

parallel in Vedic religion. The contradiction would put Fortuna both at the

origin of time and into its ensuing diachronic process: it is the comparison

offered by Vedic deity

Aditi

, the Not-Bound or Enemy of

Bondage, that shows that there is no question of choosing one of the two

apparent options: as the mother of the

Aditya

she has the same type of relationship

with one of his sons,

Dakṣa

, the minor sovereign. who represents the

Creative Energy, being at the same time his mother and daughter, as is

true for the whole group of sovereign gods to which she belongs. Moreover Aditi

is thus one of the heirs (along with

Savitr

) of the opening god of the Indoiranians,

as she is represented with her head on her two sides, with the two faces looking

opposite directions. The mother of the sovereign gods has thence two solidal but

distinct modalities of duplicity, i.e. of having two foreheads and a double

position in the genealogy. Angelo Brelich has interpreted this theology as the

basic opposition between the primordial absence of order (chaos) and the

organisation of the cosmos.

Juno and Janus

The relationship of the female sovereign deity with the god of beginnings and

passages is reflected mainly in their association with the kalendae of every

month, which belong to both, and in the festival of the

Sororium Tigillum

(better known as Tigillum

Sororium) of October 1.

Janus as gatekeeper of the gates connecting Heaven and Earth and guardian of

all passages is particularly related to time and motion. He holds the first

place in ritual invocations and prayers, in order to ensure the communication

between the worshipper and the gods. He enjoys the privilege of receiving the

first sacrifice of the new year, which is offered by the rex on the day of the

Agonium

of January as well as at the kalendae

of each month: These rites show he is considered the patron of the cosmic year.

Ovid in his Fasti

has Janus say that he is the original

Chaos and also the first era of the world, which got organised only afterwards.

He preserves a tutelary function on this universe as the gatekeeper of Heaven.

His nature, qualities and role are reflected in the myth of him being the first

to reign in Latium, on the banks of the Tiber, and there receiving god

Saturn

, in the age when the Earth still could

bear the gods. The theology of Janus is also presented in the

carmen Saliare

. According to

Johannes Lydus

the Etruscans called him Heaven.

His epithets are numerous Iunonius is particularly relevant, as the god

of the kalendae who cooperates with and is the source of the youthful vigour of

Juno in the birth of the new lunar month. His other epithet Consivius

hints to his role in the generative function.

The role of the two gods at the kalendae of every month is that of presiding

over the birth of the new moon. Janus and Juno cooperate as the first looks

after the passage from the previous to the ensuing month while the second helps

it through the strength of her vitality. The rites of the kalendae included the

invocations to Juno Covella, giving the number of days to the nonae, a

sacrifice to Janus by the rex sacrorum and the pontifex minor at the curia

Calabra and one to Juno by the regina sacrorum in the Regia: originally when

the month was still lunar the pontifex minor had the task of signalling

the appearance of the new moon. While the meaning of the epithet Covella is

unknown and debated, that of the rituals is clear as the divine couple is

supposed to oversee, protect and help the moon during the particularly dangerous

time of her darkness and her labours: the role of Juno Covella is hence

the same as that of Lucina for women during parturition. The association of the

two gods is reflected on the human level at the difficult time of labours as is

apparent in the custom of putting a key, symbol of Janus, in the hand of the

woman with the aim of ensuring an easy delivery, while she had to invoke Juno

Lucina. At the nonae Caprotinae similarly Juno had the function of aiding and

strengthening the moon as the nocturnal light, at the time when her force was

supposed to be at its lowest, after the Summer solstice.

The Tigillum Sororium was a rite (sacrum) of the gens

Horatia

and later of the State. In it Janus

Curiatius was associated to Juno Sororia: they had their altars on

opposite sides of the alley behind the Tigillum Sororium. Physically this

consisted of a beam spanning the space over two posts. It was kept in good

condition down to the time of Livy at public expenses. According to tradition it

was a rite of purification that served at the expiation of

Publius Horatius

who had murdered his own

sister when he saw her mourning the death of her betrothed Curiatius. Dumézil

has shown in his Les Horaces et les Curiaces that this story is in fact

the historical transcription of rites of reintegration into civil life of the

young warriors, in the myth symbolised by the hero, freed from their furor

(wrath), indispensable at war but dangerous in social life. What is known of the

rites of October 1 shows at Rome the legend has been used as an aetiological

myth for the yearly purification ceremonies which allowed the desacralisation

of soldiers at the end of the warring season, i.e. their cleansing from the

religious pollution contracted at war. The story finds parallels in Irish and

Indian mythologies. These rites took place in October, month that at Rome saw

the celebration of the end of the yearly military activity. Janus would then the

patron of the feria as god of transitions, Juno for her affinities to

Janus, especially on the day of the kalendae. It is also possible though that

she took part as the tutelary goddess of young people, the iuniores,

etymologically identical to her. Modern scholars are divided on the

interpretation of J. Curiatius and J. Sororia. Renard citing Capdeville opines

that the wisest choice is to adhere to tradition and consider the legend itself

as the source of the epithts.

M. Renard advanced the view that Janus and not Juppiter was the original

paredra or consort of Juno, on the grounds of their many common features,

functions and appearance in myth or rites as is shown by their cross coupled

epithets Janus Curiatius and Juno Sororia: Janus shares the epithet of Juno

Curitis and Juno the epithet Janus Geminus, as sororius means paired,

double. Renard’s theory has been rejected by G. Capdeville as not being in

accord with the level of sovereign gods in Dumezil’s trifunctional structure.

The theology of Janus would show features typically belonging to the order of

the gods of the beginning. In Capdeville’s view it is only natural that a god of

beginnings and a sovereign mother deity have common features, as all births can

be seen as beginnings, Juno is invoked by deliverers, who by custom hold a key,

symbol of Janus.

Juno and Hercules

Even though the origins of

Hercules

are undoubetdly Greek his figure

underwent an early assimilation into Italic local religions and might even

preserve traces of an association to Indoiranian deity Trita Apya that in Greece

have not survived. Among other roles that Juno and Hercules share there is the

protection of the newborn. Jean Bayet, author of Les origines de l’Arcadisme

romain, has argued that such a function must be a later development as it

looks to have supersided that of the two original Latin gods

Picumnus

and

Pilumnus

.

The two gods are mentioned together in a dedicatory inscription found in the

ruins of the temple of Hercules at Lanuvium, whose cult was ancient and second

in importance only to that of Juno Sospita. In the cults of this temple just

like in those at the

Ara maxima

in Rome women were not allowed. The

exclusion of one sex is a characteristic practice in the cults of deities of

fertility. Even though no text links the cults of the Ara maxima with Juno

Sospita, her temple, founded in 193 BC, was located in the

Forum Holitorium

near the

Porta Carmentalis

, one of the sites of the

legend of Hercules in Rome. The feria of the goddess coincides with a Natalis

Herculis, birthday of Hercules, which was celebrated with ludi circenses,

games in the circus. In Bayet’s view Juno and Hercules did superside Pilumnus

and Picumnus in the role of tutelary deities of the newborn not only because of

their own features of goddess of the deliverers and of apotropaic tutelary god

of infants but also because of their common quality of gods of fertility. This

was the case in Rome and at

Tusculum

where a cult of Juno Lucina and

Hercules was known. At Lanuvium and perhaps Rome though their most ancient

association rests on their common fertility and military characters. The Latin

Junos certainly possessed a marked warlike character (at Lanuvium, Falerii,

Tibur, Rome). Such character might suggest a comparison with the Greek armed

Heras one finds in the South of Italy at

Cape Lacinion

and at the mouth of river

Sele

, military goddesses close to the Heras of

Elis and Argos

known as Argivae. In the cult this

Hera received at Cape Lacinion she was associated with Heracles, supposed the

founder of the sanctuary. Contacts with Central Italy and similarity would have

favoured a certain assimilation between Latin warlike Junos and Argive Heras and

the association with Heracles of Latin Junos. Some scholars, mostly Italians,

recognize in the Junos of Falerii, Tibur and Lavinium the Greek Hera, rejecting

the theory of an indigenous original cult of a military Juno. Renard thinks

Dumezil’s opposition to such a view is to be upheld: Bayet’s words though did

not deny the existence of local warlike Junos, but only imply that at a certain

time they received the influence of the Heras of Lacinion and Sele, fact that

earned them the epithet of Argive and a Greek connotation. However Bayet

recognized the quality of mother and of fertility deity as being primitive among

the three purported by the epithets of the Juno of Lanuvium (Seispes, Mater,

Regina).

Magna Graecia and Lanuvium mixed their influence in the formation of the

Roman Hercules and perhaps there was a Sabine element too as is testified by

Varro, supported by the find of the sanctuary of Hercules Curinus at Sulmona and

by the existence of a Juno Curitis in Latium.

The mythical theme of the suckling of the adult

Heracles

by

Hera, though being of Greek origin, is considered by scholars as

having received its full acknowledgement and development in Etruria: Heracles

has become a bearded adult on the mirrors of the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. Most

scholars view the fact as an initiation, i.e. the accession of Heracles to the

condition of immortal. Even though the two versions coexisted in Greece and that

of Heracles infant is attested earlier Renard suggests a process more in line

with the evolution of the myth: the suckling of the adult Heracles should be

regarded as more ancient and reflecting its original true meaning.

Juno and Genius

The view that Juno was the feminine counterpart to

Genius

, i.e. that as men possess a tutelary

entity or double named genius, so women have their own one named juno,

has been maintained by many scholars, lastly Kurt Latte. In the past it has also

been argued that goddess Juno herself would be the issue of a process of

abstraction from the individual junos of every woman. According to

Georg Wissowa

and K. Latte Genius (from the

root gen-, whence gigno bear or be born, archaic also geno)

would design the specific virile generative potency, as opposed to feminine

nature, reflected in conception and delivery, under the tutelage of Juno Lucina.

Such an interpretation has been critically reviewed by

Walter F. Otto

While there are some correspondences between the ideas about genius and

juno, especially in the imperial age, the relevant documentation is rather

late (Tibullus

mentions it first). Dumezil also remarks from these passages one could infer

every woman has a Venus too. As evidence of the antiquity of the concept of a

juno of women, homologous to the genius of men, is the

Arval

sacrifice of two sheep to the Juno

Deae Diae

(“the juno of goddesses named Dea

Dia”), in contrast to their sacrifice of two cows sacrificed to Juno (singular).

However both G. Wissowa and K. Latte allow that this ritual could have been

adapted to fit theology of the Augustan restoration. While the concept of a Juno

of goddesses is not attested in the inscriptions of 58 BC from Furfo, that of a

Genius of gods is, and even of a Genius of a goddess,

Victoria

. On this point it looks remarkable

that also in

Martianus Capella

‘s division of Heaven a

Juno Hospitae Genius is mentioned in region IX, and not a Juno: the

sex of this Genius is feminine. See section below for details.

Romans believed the genius of somebody was an entity that embodied his

essential character, personality, and also originally his vital, generative

force and raison d’ être. However the genius had no direct relationship

with sex, at least in classical time conceptions, even though the nuptial bed

was named lectus genialis in honour of the Genius and brides on the day

of marriage invoked the genius of their grooms. This seems to hint to a

significance of the Genius as the propagative spirit of the gens,

of whom every human individual is an incarnation:

Censorinus

states: “Genius is the god under

whose tutelage everyone is born and lives on”, and that “many ancient authors,

among whom

Granius Flaccus

in his De Indigitamentis,

maintain that he is one and the same with the

Lar

“, meaning the Lar Familiaris. Festus calls

him “a god endowed with the power of doing everything”, then citing an Aufustius:

“Genius is the son of the gods and the parent of men, from whom men receive

life. Thence is he named my genius, because he begot me”. Festus’s quotation

goes on saying: “Other think he is the special god of every place”, a notion

that reflect a different idea. In classic age literature and iconography he is

often represented as a snake, that may appear in the conjugal bed, this

conception being perhaps the issue of a Greek influence. It was easy for the

Roman concept of Genius to expand annexing other similar religious figures as

the Lares and the Greek δαίμων αγαθός.

The genius was believed to be associated with the forehead of each man, while

goddess Juno, not the juno of every woman, was supposed to have under her

jurisdiction the eyebrows of women or to be the tutelary goddess of the eyebrows

of everybody, irrespective of one’s sex.

Heries Junonis

Among the female entities that in the pontifical invocations accompanied the

naming of gods, Juno was associated to Heries, which she shared with

Mars

(Heres Martea).

Festivals

Main article:

Matronalia

All festivals of Juno were held on the kalendae of a month except two (or,

perhaps, three): The Nonae Caprotinae on the

nonae

of July, the festival of Juno

Capitolina on September 13, because the date of these two was determined by

preeminence of Jupiter. Perhaps a second festival of Juno Moneta was held

on October 10, possibly the date of the dedication of her temple. This fact

reflects the strict association of the goddess with the beginning of each lunar

month.

Every year, on the first of March, women held a festival in honor of Juno

Lucina called the

Matronalia

.

Lucina

was an epithet for Juno as “she who

brings children into light.” On this day, lambs and cattle were sacrificed in

her honor in the temple of her sacred grove on the

Cispius

.

The second festival was devoted to Juno Moneta on June 1.

Following was the festival of the Nonae Caprotinae (“The Nones of the

Wild Fig”) held on July 7.

The festival of Juno Regina fell on September 1, followed on the 13 of

the same month by that of Juno Regina Capitolina.

October 1 was the date of the Tigillum Sororium in which the goddess

was honoured as Juno Sororia.

Last of her yearly festivals came that of Juno Sospita on February 1.

It was an appropriate date for her celebration since the month of February was

considered a perilous time of passage, the cosmic year coming then to an end and

the limits between the world of the living and the underworld being no longer

safely defined. Hence the community invoked the protection (tutela) of

the warlike Juno Sospita, “The Saviour“.

Juno is the patroness of marriage, and many people believe that the most

favorable time to marry is June, the month named after the goddess.

Etrurian Uni, Hera, Astarte and Iuno

The Etruscans were a people who entertained strict (if often conflicting)

contacts with the other peoples of the Mediterranean: the Greeks, the

Phoenicians and the Carthaginians.

Testimony of intense cultural exchanges with the Greeks have been found in

1969 at the sanctuary of the port of Gravisca near

Tarquinia

. Renard thinks the cult of Hera in

great emporia such as

Croton

, Posidonia, Pyrgi might be a counter to

Aphrodite’s, linked to sacred prostitution in ports, as the sovereign of

legitimate of marriage and family and of their sacrality. Hera’s presence had

already been attested at

Caere

in the sanctuary of Manganello. In the

18th century a dedication to Iuno Historia was discovered at Castrum Novum

(Santa Marinella). The cult of Iuno and Hera is generally attested in Etruria.

The relationship between Uni and the Phoenician goddess

Astarte

has been brought to light by the

discovery of the

Pyrgi Tablets

in 1964. At

Pyrgi

, one of the ports of Caere, excavations

had since 1956 revealed the existence of a sacred area, intensely active from

the last quarter of the 4th century, yielding two documents of a cult of

Uni

. Scholars had long believed Etruscan

goddess Uni was strongly influenced by the Argive Heras and had her Punic

counterpart in Carthaginian goddess

Tanit

, identified by the Romans as Juno

Caelestis. Nonetheless

Augustin

had already stated that Iuno was named

Astarte in the Punic language, notion that the discovery of the Pyrgi lamellae

has proved correct. It is debated whether such an identification was linked to a

transient political stage corresponding with Tefarie Velianas’s Carthagenian-backed

tyranny on Caere as the sanctuary does not show any other trait proper to

Phoenician ones. The mention of the goddess of the sanctuary as being named

locally Eileitheia and Leucothea by different Greek authors narrating its

destruction by the Syracusean fleet in 384 BC, made the picture even more

complex. R. Bloch has proposed a two stage interpretation: the first thonym

Eilethya corresponds to Juno Lucina, the second Leuchothea to Mater Matuta.

However, the local theonym is Uni and one would legitimately expect it to be

translated as Hera. A fragmentary bronze lamella discovered on the same site and

mentioning both theonym Uni and Thesan (i. e. Latin Juno and Aurora-Mater Matuta)

would then allow the inference of the integration of the two deities at Pyrgi:

the local Uni-Thesan matronal and auroral, would have become the Iuno Lucina and

the Mater Matuta of Rome. The Greek assimilation would reflect this process as

not direct but subsequent to a process of distinction. Renard rejects this

hypothesis since he sees in Uni and Thesan two distinct deities, though

associated in cult. However the entire picture should have been familiar in

Italian and Roman religious lore as is shown by the complexity and ambivalence

of the relationship of Juno with the Rome and Romans in Virgil’s Aeneid, who has

Latin, Greek and Punic traits, result of a plurisaecular process of

amalgamation. Also remarkable in this sense is the Fanum Iunonis of Malta

(of the Hellenistic period) which has yielded dedicatory inscriptions to Astarte

and Tanit.

Juno in Martianus Capella’s division of Heaven

Martianus Capella’s collocation of gods into sixteen different regions of

Heaven is supposed to be based on and to reflect Etruscan religious lore, at

least in part. It is thence comparable with the theonyms found in the sixteen

cases of the outer rim of the

Piacenza Liver

. Juno is to be found in region

II, along with Quirinus Mars, Lars militaris, Fons, Lymphae and the dii

Novensiles. This position is reflected on the

Piacenza Liver

by the situation of Uni in case

IV, owing to a threefold location of

Tinia

in the first three cases that determines

an equivalent shift.

An entity named Juno Hospitae Genius is to be found alone in region IX. Since

Grotius

(1599) many editors have proposed the

correction of Hospitae into Sospitae. S. Weinstock has proposed to identify this

entity with one of the spouses of

Neptune

, as the epithet recurs below (I 81)

used in this sense.

In region XIV is located Juno Caelestis along with

Saturn

. This deity is the Punic Astarte_Tanit,

usually associated with Saturn in Africa. Iuno Caelestis is thence in turn

assimilated to Ops

and Greek

Rhea

. Uni is here the Punic goddess, in accord

with the identification of Pyrgi. Her paredra was the Phoenician god

Ba’al

, interpreted as Saturn. Capdeville admits

of being unable to explain the collocation of Juno Caelestis among the

underworld gods, which looks to be determined mainly by her condition of spouse

of Saturn.

Statue at Samos

In the Dutch

city of

Maastricht

, which was founded as Trajectum

ad Mosam about 2000 years ago, the remains of the foundations of a

substantial temple for Juno and Jupiter are to be found in the cellars of Hotel

Derlon. Over part of the Roman remains the first Christian church of the

Netherlands was built in the 4th century AD.

The story behind these remains begins with Juno and Jupiter being born as

twins of

Saturn

and

Opis. Juno was sent to

Samos

when she was a very young child. She was

carefully raised there until

puberty

, when she then married her brother. A

statue was made representing Juno, the bride, as a young girl on her wedding

day. It was carved out of

Parian marble

and placed in front of her temple

at Samos for many centuries. Ultimately this statue of Juno was brought to Rome

and placed in the sanctuary of

Jupiter Optimus Maximus

on the

Capitoline Hill

. For a long time the Romans

honored her with many ceremonies under the name Queen Juno. The remains were

moved then sometime between the 1st century and the 4th century to the

Netherlands.

In literature

Perhaps Juno’s most prominent appearance in

Roman literature

is as the primary antagonistic

force in Virgil

‘s

Aeneid

, where she is depicted as a cruel

and savage goddess intent upon supporting first

Dido

and then

Turnus

and the

Rutulians

against

Aeneas

‘ attempt to found a new

Troy in Italy. There has been some speculation—such as by

Maurus Servius Honoratus

, an ancient

commentator on the Aeneid—that she is perhaps a conflation of

Hera with the

Carthaginian

storm-goddess

Tanit

in some aspects of her portrayal here.

Juno is also mentioned in

The Tempest

in Act IV, Scene I; she appears

in a supernatural masque, portrayed by spirits conjured by Prospero. She relates

to Prospero as they are both leaders in their realm and have spirit like

messengers who are very loyal (Juno has Iris, Prospero has Ariel).

William Shakespeare

repeatedly mentions Juno

throughout the play

Antony and Cleopatra

, often in forms of

exclamation by the characters.

Juno is a major character in the

Heroes of Olympus

series by

Rick Riordan

. Her goal in the series is to

bring the Greek and Roman demigods together against the

Gigantes

. She had earlier been a supporting

character in the

Percy Jackson & the Olympians

series, under

the name Hera

.

Gaius

Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (206 – August, 253), was

Roman

Emperor

from 251 to 253, in a joint rule with his son

Volusianus

.

Gallus was born in Italy, in a family with respected ancestry

of

Etruscan

senatorial

background. He had two children in his marriage with

Afinia Gemina Baebiana

: Gaius Vibius Volusianus, later Emperor, and a

daughter, Vibia Galla. His early career was a typical

cursus honorum

, with several appointments, both political and military.

He was suffect consul

and in 250 was nominated governor of the

Roman province

of

Moesia Superior

,

an appointment that showed the confidence of emperor

Trajan Decius

in him. In Moesia, Gallus was a key figure in repelling the

frequent invasion attacks by the

Gothic

tribes of

the Danube

and

became popular with the army, catered to during his brief Imperial rule by his

official image: military haircut, gladiatorial physique, intimidating stance (illustration,

left).[1]

In June 251, Decius and his co-emperor and son

Herennius Etruscus

died in the

Battle of Abrittus

, at the hands of the Goths they were supposed to punish

for raids into the empire, largely owing to the failure of Gallus to attack

aggressively. When the army heard the news, the soldiers proclaimed Gallus

emperor, despite

Hostilian

,

Decius’ surviving son, ascending the imperial throne in Rome. Gallus did not

back down from his intention to become emperor, but accepted Hostilian as

co-emperor, perhaps to avoid the damage of another civil war. While Gallus

marched on Rome, an outbreak of

plague

struck the city and killed young Hostilian. With absolute power now

in his hands, Gallus nominated his son Volusianus co-emperor.

Eager to show himself competent and gain popularity with the

citizens, Gallus swiftly dealt with the epidemic, providing burial for the

victims. Gallus is often accused of persecuting the

Christians

, but the only solid evidence of this allegation is the

imprisoning of

Pope Cornelius

in 252.

Like his predecessors, Gallus did not have an easy reign. In

the East, Persian Emperor

Shapur I

invaded and conquered the province of

Syria

, without any response from Rome. On the Danube, the Gothic tribes were

once again on the loose, despite the peace treaty signed in 251. The army was

not long pleased with the emperor, and when

Aemilianus

,

governor of Moesia Superior and Pannonia, took the initiative of battle and

defeated the Goths, the soldiers proclaimed him emperor. With a

usurper

threatening the throne, Gallus prepared for a fight. He recalled

several legions

and ordered reinforcements to return to Rome from the

Rhine

frontier.

Despite these dispositions, Aemilianus marched onto Italy ready to fight for his

claim. Gallus did not have the chance to face him in battle: he and

Volusianus

were murdered by their own troops in August 253, in

Interamna (modern

Terni)

.

Bronze of Gallus dating from the time of his reign as

Roman Emperor, the only surviving near-complete full-size 3rd century Roman

bronze (Metropolitan

Museum of Art)[2]

|