|

The

Seleucid

Kingdom

Antiochos

VII, Euergetes (Sidetes) –

Seleucid King: 138-129 B.C.

Bronze 18mm (5.67 grams) Struck 138-129 B.C.

Reference: Sear 7098

Winged bust of

Eros

(Cupid) right wreathed with myrtle.

Head-dress of

Isis

; on right, ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ / ANTIOXOY; on left, EYEPΓETOY;

MH

monogram in left field, beneath, crescent and Seleucid date ΔOP (=174=138 B.C.)

—

Almost alone amongst the later Seleukid monarchs, ANtiochos

VII ruled with competence and integrity. He was the younger borther of Demetrios

II, and following the latter’s capture by the Parthians he seized power and

quickly disposed of the usurper Tryphon. He campaiged with success in Palestine

and Babylonia, but in 129 B.C. he was killed in battle against the Parthians.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured,

provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of

Authenticity.

In

Roman mythology

,

Cupid (Latin cupido,

meaning “desire”) is the god of desire, affection and

erotic

love. He is often portrayed as the son of the goddess

Venus

, with a father rarely mentioned. His

Greek counterpart

is

Eros. Cupid is also known in Latin as Amor (“Love”). The

Amores (plural) or amorini in the later terminology of

art history

are the equivalent of the Greek

Erotes

.

Although Eros appears in

Classical

Greek art

as a slender winged youth, during the

Hellenistic period

he was increasingly

portrayed as a chubby boy. During this time, his iconography acquired the bow

and arrow that remain a distinguishing attribute; a person, or even a deity, who

is shot by Cupid’s arrow is filled with uncontrollable desire. The Roman Cupid

retains these characteristics, which continue in the depiction of multiple

cupids in both

Roman art

and the later

classical tradition

of

Western art

.

Cupid’s ability to compel love and desire plays an instigating role in

several myths or literary scenarios. In

Vergil

‘s

Aeneid

, Cupid prompts

Dido

to fall in love with

Aeneas

, with tragic results.

Ovid makes Cupid the patron of love poets. Cupid is a central

character, however, in only the traditional tale of

Cupid and Psyche

, as told by

Apuleius

.

Cupid was a continuously popular figure in the

Middle Ages

, when under Christian influence he

often had a dual nature as Heavenly and Earthly love, and in the

Renaissance

, when a renewed interest in

classical philosophy endowed him with complex allegorical meanings. In

contemporary popular culture, Cupid is shown shooting his bow to inspire

romantic love, often as an icon of

Valentine’s Day

.

Legend

In the Roman version, Cupid was the son of Venus (goddess of hope) and Mars

(god of war).[2][3]

In the Greek version he was named

Eros and seen as one of the

primordial gods

(though other myths exist as

well). Cupid was often depicted with wings, a bow, and a quiver of arrows. The

following story of

Cupid and Psyche

is almost identical in both

cultures; the most familiar version is found in the

Metamorphoses

of

Apuleius

. When Cupid’s mother Venus became

jealous of the princess

Psyche

, who was so beloved by her subjects that

they forgot to worship Venus, she ordered Cupid to make Psyche fall in love with

the vilest thing in the world. While Cupid was sneaking into her room to shoot

Psyche with a golden arrow, he accidentally scratched himself with his own arrow

and fell deeply in love with her.

Following that, Cupid visited Psyche every night while she slept. Speaking to

her so that she could not see him, he told her to never try to see him. Psyche,

though, incited by her two older sisters who told her Cupid was sparcker [a

monster], tried to look at him and angered Cupid. When he left, she looked all

over the known world for him until at last Venus told her that she would help

her find Cupid if she did the tasks presented to her by Venus. Psyche agreed.

Psyche completed every task presented to her, each one harder than the last.

Finally, Venus had one task left – Psyche had to give Pluto a box containing

something Psyche was not to look at. Psyche’s curiosity got the best of her and

she looked in the box. Hidden within it was eternal sleep placed there by Venus.

Cupid was no longer angered by Psyche and brought her from her sleep. Jupiter,

the leader of the gods, gave Psyche the gift of immortality so that she could be

with him. Together they had a daughter,

Voluptas

, or

Hedone

, (meaning pleasure) and Psyche became a

goddess. Her name “Psyche” means “soul.”

Portrayal

Caravaggio

‘s

Amor Vincit Omnia

In painting and sculpture, Cupid is often portrayed as a

nude

(or sometimes

diapered

) winged boy or baby (a

putto

) armed with a bow and a quiver of arrows.

On gems and other surviving pieces, Cupid is usually shown amusing himself

with adult play, sometimes driving a hoop, throwing darts, catching a butterfly,

or flirting with a nymph

. He is often depicted with his mother (in

graphic arts, this is nearly always Venus), playing a horn. In other images, his

mother is depicted scolding or even spanking him due to his mischievous nature.

He is also shown wearing a helmet and carrying a buckler, perhaps in reference

to Virgil

‘s Omnia vincit amor or as

political satire

on wars for love or love as

war.

Cupid figures prominently in

ariel poetry

, lyrics and, of course,

elegiac

love and

metamorphic poetry

. In epic poetry, he is less

often invoked, but he does appear in

Virgil

‘s

Aeneid

changed into the shape of

Ascanius

inspiring

Dido’s

love. In later literature, Cupid is

frequently invoked as fickle, playful, and perverse. He is often depicted as

carrying two sets of arrows: one set gold, which inspire true love; and the

other lead-headed, which inspire erotic love.

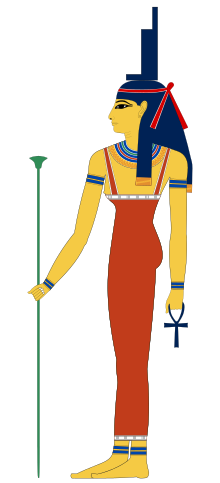

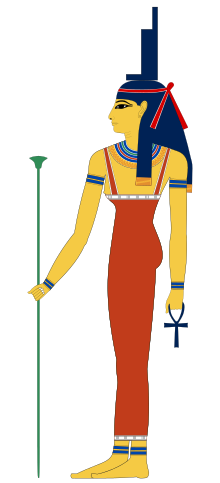

The goddess Isis portrayed as a woman, wearing a headdress shaped

like a throne and with an Ankh in her hand

Isis (Ancient

Greek: Ἶσις, original

Egyptian

pronunciation more likely Aset)

is a goddess in

Ancient Egyptian

religious beliefs

, whose worship spread

throughout the

Greco-Roman world

. She was worshipped as the

ideal mother and wife as well as the patroness of nature and magic. She was the

friend of

slaves

,

sinners,

artisans

, and the downtrodden, and she listened

to the prayers of the wealthy, maidens, aristocrats, and rulers.Isis is often

depicted as the mother of

Horus

, the hawk-headed god of war and

protection (although in some traditions Horus’s mother was

Hathor

). Isis is also known as protector of the

dead and goddess of children.

The name Isis means “Throne”.Her headdress is a throne. As the

personification of the throne, she was an important representation of the

pharaoh’s power. The pharaoh was depicted as her child, who sat on the throne

she provided. Her

cult

was popular throughout Egypt, but her most

important

temples

were at Behbeit El-Hagar in the

Nile delta

, and, beginning in the reign with

Nectanebo I (380–362 BCE), on the island of

Philae

in Upper Egypt.

In the typical form of her myth, Isis was the first daughter of

Geb,

god of the Earth, and

Nut

, goddess of the Sky, and she was born on

the fourth

intercalary day

. She married her brother,

Osiris

, and she conceived Horus with him. Isis

was instrumental in the resurrection of Osiris when he was murdered by

Set

. Using her magical skills, she restored his

body to life after having gathered the body parts that had been strewn about the

earth by Set.

This myth became very important during the Greco-Roman period. For example it

was believed that the

Nile River

flooded every year because of the

tears of sorrow which Isis wept for Osiris. Osiris’s death and rebirth was

relived each year through rituals. The worship of Isis eventually spread

throughout the Greco-Roman world, continuing until the suppression of

paganism

in the Christian era.The popular motif

of Isis suckling her son Horus, however, lived on in a Christianized context as

the popular image of Mary suckling the infant son Jesus from the fifth century

onward.

Etymology

The name Isis is the Greek version of her name, with a final -s

added to the original Egyptian form because of the grammatical requirements of

the Greek language (-s often being a marker of the

nominative case

in ancient Greek).

The Egyptian name was recorded as ỉs.t or

ȝs.t and meant “(She of the Throne”). The

true Egyptian pronunciation remains uncertain, however, because

hieroglyphs

do not indicate

vowels

. Based on recent studies which present

us with approximations based on contemporary languages (specifically, Greek) and

Coptic

evidence, the reconstructed

pronunciation of her name is *Usat

[*ˈʔyːsəʔ]

. Osiris’s name, *Usir

also starts with the throne glyph ʔs.[7]

For convenience,

Egyptologists

arbitrarily choose to pronounce

her name as “ee-set”. Sometimes they may also say “ee-sa” because the final “t”

in her name was a feminine

suffix

, which is known to have been dropped in

speech

during the last stages of the Egyptian

and Greek languages.

Principal

features of the cult

Origins

Isis depicted with outstretched wings (wall painting, c. 1360 BCE)

Most Egyptian deities were first worshipped by very local cults, and they

retained those local centres of worship even as their popularity spread, so that

most major cities and towns in Egypt were known as the home of a particular

deity. The origins of the cult of Isis are uncertain, but it is believed that

she was originally an independent and popular deity in

predynastic

times, prior to 3100 BCE, at

Sebennytos

in the Nile delta.[3]

The first written references to Isis date back to the

Fifth dynasty of Egypt

. Based on the

association of her name with the throne, some early Egyptologists believed that

Isis’s original function was that of throne-mother.[citation

needed] However, more recent scholarship suggests

that aspects of that role came later by association. In many African tribes, the

throne is known as the mother of the king, and that concept fits well

with either theory, possibly giving insight into the thinking of ancient

Egyptians.

Classical Egyptian

period

During the

Old Kingdom

period, Isis was represented as the

wife or assistant to the deceased pharaoh. Thus she had a funerary association,

her name appearing over eighty times in the pharaoh’s funeral texts (the

Pyramid Texts

). This association with the

pharaoh’s wife is consistent with the role of Isis as the spouse of Horus, the

god associated with the pharaoh as his protector, and then later as the

deification of the pharaoh himself.

But in addition, Isis was also represented as the mother of the “four suns of

Horus”, the four deities who protected the

canopic jars

containing the pharaoh’s internal

organs. More specifically, Isis was viewed as the protector of the

liver

-jar-deity,

Imsety

.[8]

By the

Middle Kingdom

period, as the funeral texts

began to be used by members of Egyptian society other than the royal family, the

role of Isis as protector also grew, to include the protection of nobles and

even commoners.[citation

needed]

Isis nursing Horus (Louvre)

By the

New Kingdom

period, the role of Isis as a

mother deity had displaced that of the spouse. She was seen as the mother of the

pharaoh, and was often depicted breastfeeding the pharaoh. It is theorized that

this displacement happened through the merging of cults from the various cult

centers as Egyptian religion became more standardized.[citation

needed] When the cult of

Ra

rose to prominence, with its cult center at

Heliopolis

, Ra was identified with the similar

deity, Horus. But Hathor had been paired with Ra in some regions, as the mother

of the god. Since Isis was paired with Horus, and Horus was identified with Ra,

Isis began to be merged with Hathor as Isis-Hathor. By merging with

Hathor, Isis became the mother of Horus, as well as his wife. Eventually the

mother role displaced the role of spouse. Thus, the role of spouse to Isis was

open and in the Heliopolis pantheon, Isis became the wife of Osiris and the

mother of Horus/Ra. This reconciliation of themes led to the evolution of the

myth of Isis and Osiris

.[8]

Temples and priesthood

Little information on Egyptian rituals for Isis survives; however, it is

clear there were both priests and priestesses officiating at her cult throughout

its history. By the Greco-Roman era, many of them were considered

healers

, and were said to have other special

powers, including dream interpretation and the ability to control the

weather

, which they did by braiding or not

combing their hair.[citation

needed] The latter was believed because the

Egyptians considered knots

to have magical powers.

The cult of Isis and Osiris continued up until the 6th century CE on the

island of Philae in Upper Nile. The

Theodosian decree

(in about 380 CE) to destroy

all pagan temples was not enforced there until the time of

Justinian

. This toleration was due to an old

treaty made between the Blemyes-Nobadae and the emperor

Diocletian

. Every year they visited Elephantine

and at certain intervals took the image of Isis up river to the land of the

Blemyes for

oracular

purposes before returning it.

Justinian sent Narses

to destroy the sanctuaries, with the

priests being arrested and the divine images taken to Constantinople.[9]

Philae

was the last of the ancient Egyptian

temples to be closed.

Iconography

Associations

Due to the association between knots and magical power, a symbol of Isis was

the tiet or tyet

(meaning welfare/life),

also called the Knot of Isis, Buckle of Isis, or the

Blood

of Isis, which is shown to the right.

In many respects the tyet resembles an

ankh, except that its arms point downward, and when used as such,

seems to represent the idea of

eternal life

or

resurrection

. The meaning of Blood of Isis

is more obscure, but the tyet often was used as a funerary

amulet

made of red

wood,

stone

, or

glass

, so this may simply have been a

description of the appearance of the materials used.

The star Sopdet

(Sirius)

is associated with Isis. The appearance of the star signified the advent of a

new year and Isis was likewise considered the goddess of rebirth and

reincarnation, and as a protector of the dead. The Book of the Dead outlines a

particular ritual that would protect the dead, enabling travel anywhere in the

underworld, and most of the titles Isis holds signify her as the goddess of

protection of the dead.

Probably due to assimilation with the goddess Aphrodite (Venus),

during the Roman period, the

rose was used in her worship. The demand for roses throughout the

empire turned rose production into an important industry.

Depictions

Isis nursing

Horus

, wearing the headdress of

Hathor

.

In art, originally Isis was pictured as a woman wearing a long sheath dress

and crowned with the

hieroglyphic

sign for a throne.

Sometimes she is depicted as holding a

lotus

, or, as a

sycamore

tree. One pharaoh,

Thutmose III

, is depicted in his tomb as

nursing from a sycamore tree that had a breast.

After she assimilated many of the roles of Hathor, Isis’s headdress is

replaced with that of Hathor: the horns of a cow on her head, with the solar

disk between them. Sometimes she also is represented as a cow, or a cow’s head.

Usually, however, she is depicted with her young child, Horus (the pharaoh),

with a

crown

, and a

vulture

. Occasionally she is represented as a

kite

flying above the body of Osiris or with

the dead Osiris across her lap as she worked her magic to bring him back to

life.

Most often Isis is seen holding only the generic

ankh sign and a simple staff, but in late images she is seen

sometimes with items usually associated only with Hathor, the sacred

sistrum

rattle and the fertility-bearing

menat

necklace

. In

The Book of Coming Forth By Day

Isis is

depicted standing on the prow of the

Solar Barque

with her arms outstretched.[1]

Mythology

Sister-wife to Osiris

During the

Old Kingdom

period, the pantheons of individual

Egyptian cities varied by region. During the

5th dynasty

, Isis entered the pantheon of the

city of

Heliopolis

. She was represented as a daughter

of Nut and Geb, and sister to Osiris,

Nephthys

, and Set. The two sisters, Isis and

Nephthys, often were depicted on coffins, with wings outstretched, as protectors

against evil. As a funerary deity, she was associated with Osiris, lord of the

underworld, and was considered his wife.

Rare

terracotta

image of Isis lamenting

the loss of Osiris (eighteenth dynasty)

Musée du Louvre

,

Paris

.

A later myth, when the cult of Osiris gained more authority, tells the story

of Anubis

, the god of the underworld. The tale

describes how Nephthys was denied a child by Set and disguised herself as the

much more attractive Isis to seduce him. The plot failed, but Osiris now found

Nephthys very attractive, as he thought she was Isis. They

had sex

, resulting in the birth of Anubis.

Alternatively, Nephthys intentionally assumed the form of Isis in order to trick

Osiris into fathering her son.

In fear of Set’s retribution, Nephthys persuaded Isis to adopt Anubis, so

that Set would not find out and kill the child. The tale describes both why

Anubis is seen as an underworld deity (he becomes a son of Osiris), and why he

could not inherit Osiris’s position (he was not a legitimate heir in this new

birth scenario), neatly preserving Osiris’s position as lord of the underworld.

It should be remembered, however, that this new myth was only a later creation

of the Osirian cult who wanted to depict Set in an evil position, as the enemy

of Osiris.

The most extensive account of the Isis-Osiris story known today is Plutarch’s

Greek description written in the 1st century CE, usually known under its Latin

title De Iside et Osiride.[11]

In that version, Set held a banquet for Osiris in which he brought in a

beautiful box and said that whoever could fit in the box perfectly would get to

keep it. Set had measured Osiris in his sleep and made sure that he was the only

one who could fit the box. Several tried to see whether they fit. Once it was

Osiris’s turn to see if he could fit in the box, Set closed the lid on him so

that the box was now a coffin for Osiris. Set flung the box in the Nile so that

it would drift far away. Isis went looking for the box so that Osiris could have

a proper burial. She found the box in a tree in

Byblos

, a city along the Phoenician coast, and

brought it back to Egypt, hiding it in a swamp. But Set went hunting that night

and found the box. Enraged, Set chopped Osiris’s body into fourteen pieces and

scattered them all over Egypt to ensure that Isis could never find Osiris again

for a proper burial.[12][13]

Isis and her sister Nephthys went looking for these pieces, but could only

find thirteen of the fourteen. Fish had swallowed the last piece, his

phallus

, so Isis made him a new one with magic,

putting his body back together after which they conceived Horus. The number of

pieces is described on temple walls variously as fourteen and sixteen, and

occasionally

forty-two

, one for each

nome

or district.[13]

Mother of Horus

Yet another set of late myths detail the adventures of Isis after the birth

of Osiris’s posthumous son,

Horus

. Isis was said to have given birth to

Horus at Khemmis, thought to be located on the Nile Delta.[14]

Many dangers faced Horus after birth, and Isis fled with the newborn to escape

the wrath of

Set

, the murderer of her husband. In one

instance, Isis heals Horus from a lethal scorpion sting; she also performs other

miracles in relation to the

cippi

, or the plaques of Horus. Isis

protected and raised Horus until he was old enough to face Set, and

subsequently, became the pharaoh of Egypt.

Magic

It was said that Isis tricked

Ra

(i.e. Amun-Ra/Atum-Ra) into telling her his “secret name,” by

causing a

snake

to bite him, for which only Isis had the

cure. Knowing the secret name of a deity enabled one to have power of the deity.

The use of secret names became central in late Egyptian magic spells, and Isis

often is implored to “use the true name of Ra” in the performance of rituals. By

the late Egyptian historical period, after the occupations by the Greeks and the

Romans, Isis became the most important and most powerful deity of the Egyptian

pantheon because of her magical skills.

Magic

is central to the entire mythology of

Isis, arguably more so than any other Egyptian deity.

Isis had a central role in Egyptian magic spells and ritual, especially those

of protection and healing. In many spells, she also is completely merged even

with Horus, where invocations of Isis are supposed to involve Horus’s powers

automatically as well. In Egyptian history the image of a wounded Horus became a

standard feature of Isis’s healing spells, which typically invoked the curative

powers of the milk of Isis.

Greco-Roman world

Interpretatio graeca

Isis (seated right) welcoming the

Greek heroine

Io

as she is borne into Egypt on

the shoulders of the personified Nile, as depicted in a Roman wall

painting from

Pompeii

Using the comparative methodology known as

interpretatio graeca

, the Greek historian

Herodotus

(5th century BCE) described Isis by

comparison with the Greek goddess

Demeter

, whose

mysteries

at

Eleusis

offered initiates guidance in the

afterlife and a vision of rebirth. Herodotus says that Isis was the only goddess

worshiped by all Egyptians alike.[16]

Terracotta figure of Isis-Aphrodite from

Ptolemaic Egypt

After the conquest of Egypt by

Alexander the Great

and the

Hellenization

of the Egyptian culture initiated

by

Ptolemy I Soter

, Isis became known as

Queen of Heaven

.[17]

Other Mediterranean goddesses, such as Demeter,

Astarte

, and

Aphrodite

, became identified with Isis, as was

the Arabian goddess Al-Ozza or Al-Uzza through a similarity of name, since

etymology was thought to reveal the essential or primordial nature of the thing

named.[18]

An alabaster statue of Isis from the 3rd century BCE, found in

Ohrid

, in the

Republic of Macedonia

, is depicted on the

obverse

of the Macedonian 10

denars

banknote, issued in 1996.[19]

Isis in the Roman

Empire

Roman Isis holding a sistrum and

oinochoe

and wearing a garment tied

with a characteristic knot, from the time of

Hadrian

(117–138 CE)

Tacitus

writes that after the

assassination of Julius Caesar

, a temple in

honour of Isis had been decreed, but was suspended by Augustus as part of his

program to restore

traditional Roman religion

. The emperor

Caligula

, however, was open to Eastern

religions, and the

Navigium Isidis

, a procession in honor of

Isis, was established in Rome during his reign.[20]

According to the Jewish historian

Josephus

, Caligula donned female garb and took

part in the mysteries he instituted.

Vespasian

, along with

Titus

, practised

incubation

in the Roman

Iseum

.

Domitian

built another Iseum along with a

Serapeum

. In a

relief

on the

Arch of Trajan

, the emperor appears before Isis

and Horus, presenting them with votive offerings of wine.[20]

Hadrian

decorated his villa at

Tibur

with Isiac scenes.

Galerius

regarded Isis as his protector.[21]

The religion of Isis thus spread throughout the

Roman Empire

during the formative centuries of

Christianity. Wall paintings and objects reveal her pervasive presence at

Pompeii

, preserved by the

eruption of Vesuvius

in 79 CE. In Rome, temples

were built and obelisks erected in her honour. In Greece, the cult of Isis was

introduced to traditional centres of worship in

Delos

,

Delphi

,

Eleusis

and

Athens

, as well as in northern Greece. Harbours

of Isis were to be found on the Arabian Sea and the Black Sea. Inscriptions show

followers in Gaul, Spain, Pannonia, Germany, Arabia, Asia Minor, Portugal and

many shrines even in Britain.[22]

Tacitus interprets a goddess among the Germanic

Suebi

as

a form of Isis

whose symbol (signum) was

a ship.[23]

Bruce Lincoln

regards the identity of this

Germanic goddess as “elusive.”[24]

The Greek antiquarian

Plutarch

wrote a treatise on Isis and Osiris,[25]

a major source for Imperial theology concerning Isis.[11]

Plutarch describes Isis as “a goddess exceptionally wise and a lover of wisdom,

to whom, as her name at least seems to indicate, knowledge and understanding are

in the highest degree appropriate… .” The statue of Athena in

Sais

was identified with Isis, and according to

Plutarch was inscribed “I am all that has been, and is, and shall be, and my

robe no mortal has yet uncovered.”[26]

At Sais, however, the patron goddess of the ancient cult was

Neith

, many of whose traits had begun to be

attributed to Isis during the Greek occupation.

The Roman writer

Apuleius

recorded aspects of the cult of Isis

in the 2nd century CE, including the Navigium Isidis, in his novel

The Golden Ass

. The protagonist Lucius

prays to Isis as Regina Caeli, “Queen of Heaven”:

You see me here, Lucius, in answer to your prayer. I am nature, the

universal Mother, mistress of all the elements, primordial child of

time, sovereign of all things spiritual, queen of the dead, queen of the

ocean, queen also of the immortals, the single manifestation of all gods

and goddesses that are, my nod governs the shining heights of Heavens,

the wholesome sea breezes. Though I am worshipped in many aspects, known

by countless names … the Egyptians who excel in ancient learning and

worship call me by my true name…Queen Isis.[27]

Ruins of the Temple of Isis in Delos

According to Apuleius, these other names include manifestations of the

goddess as

Ceres

, “the original nurturing parent”;

Heavenly Venus (Venus Caelestis); the “sister of

Phoebus

“, that is, Diana or

Artemis

as she is

worshipped at Ephesus

; or

Proserpina

(Greek

Persephone

) as the triple goddess of the

underworld.[28]

From the middle Imperial period, the title Caelestis, “Heavenly” or

“Celestial”, is attached to several goddesses embodying aspects of a single,

supreme Heavenly Goddess. The Dea Caelestis was identified with the

constellation Virgo (the Virgin)

, who holds the

divine balance of justice

.

Greco-Roman temples

On the Greek island of

Delos

a

Doric

Temple of Isis was built on a high

over-looking hill at the beginning of the Roman period to venerate the familiar

trinity of Isis, the Alexandrian

Serapis

and

Harpocrates

. The creation of this temple is

significant as Delos is particularly known as the birthplace of the Greek gods

Artemis

and

Apollo

who had temples of their own on the

island long before the temple to Isis was built.

In the Roman Empire, a well-preserved example was discovered in

Pompeii

.The only sanctuary of Isis (fanum

Isidis) identified with certainty in

Roman Britain

is located in

Londinium

(present-day London).[29]

Isis in black and white marble (Roman, 2nd century CE)

Late antiquity

The cult of Isis was part of the

syncretic

tendencies of religion in the

Greco-Roman world of

late antiquity

. The male first name “Isidore”

in Greek means “gift of Isis” (similar to “Theodore“,

“God’s gift”).

The Isis cult in Rome was a template for the Christian

Madonna

cult.

Eros, in

Greek mythology

, was the

primordial god

of sexual love and beauty. He

was also worshipped as a fertility deity. His

Roman

counterpart was

Cupid

(“desire”), also known as Amor (“love”).

In some myths, he was the son of the deities

Aphrodite

and Ares

, but according to Plato’s

Symposium

, he was conceived by Poros (Plenty)

and Penia (Poverty) at Aphrodite’s birthday. Like

Dionysus

, he was sometimes referred to as

Eleut![Eros1st c. BCE marble from Pompeii. This statue is also known as Eros Centocelle, and is thought to be a copy of the colossal Eros of Thespiae, a work by Praxiteles.[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Eros_Farnese_MAN_Napoli_6353.jpg/150px-Eros_Farnese_MAN_Napoli_6353.jpg) herios, herios,

“the liberator”.

Antiochus VII Euergetes, nicknamed Sidetes

(from Side

), ruler

of the

Hellenistic

Seleucid Empire

, reigned from 138 to 129 BC. He was the last Seleucid king

of any stature.

The brother of

Demetrius II

, Antiochus was elevated after Demetrius’ capture by the

Parthians

. He

married

Cleopatra Thea

, who had been the wife of Demetrius. Their offspring was

Antiochus IX

, who thus became both half-brother and cousin to

Seleucus V

and

Antiochus VIII

.

Sidetes defeated the usurper

Tryphon

at

Dora

[1]

and laid siege to

Jerusalem

in 134. According to

Josephus

the Hasmonean

king John Hyrcanus

opened King

David

‘s sepulchre

and removed three thousand talents, which he then paid Antiochus to spare the

city. Sidetes then attacked the Parthians, supported by a body of Jews under

Hyrcanus, and briefly took back

Mesopotamia

,

Babylonia

and Media

before

being ambushed and killed by

Phraates II

. His brother

Demetrius II

had by then been released, but the Seleucid realm was now

restricted to Syria

.

The

Seleucid Empire (//;

from

Greek

: Σελεύκεια,

Seleúkeia) was a

Hellenistic

state ruled by the Seleucid dynasty

founded by

Seleucus I Nicator

following the division of

the empire created by

Alexander the Great

. Seleucus received

Babylonia

and, from there, expanded his

dominions to include much of Alexander’s

near eastern

territories. At the height of its

power, it included central

Anatolia

, the

Levant

,

Mesopotamia

,

Kuwait

,

Persia

,

Afghanistan

,

Turkmenistan

, and northwest parts of

India

.

The Seleucid Empire was a major center of

Hellenistic

culture that maintained the

preeminence of

Greek

customs where a Greek-Macedonian

political elite dominated, mostly in the urban areas. The Greek population of

the cities who formed the dominant elite were reinforced by emigration from

Greece

. Seleucid expansion into

Anatolia

and Greece was abruptly halted after

decisive defeats

at the hands of the

Roman army

. Their attempts to defeat their old

enemy

Ptolemaic Egypt

were frustrated by Roman

demands. Much of the eastern part of the empire was conquered by the

Parthians

under

Mithridates I of Parthia

in the mid-2nd century

BC, yet the Seleucid kings continued to rule a

rump state

from

Syria

until the invasion by

Armenian

king

Tigranes the Great

and their ultimate overthrow

by the Roman

general

Pompey

.

History

Partition

of Alexander’s empire

Alexander

conquered the

Persian Empire

under its last Achaemenid

dynast, Darius III

, within a short time frame and died

young, leaving an expansive empire of partly Hellenised culture without an adult

heir. The empire was put under the authority of a regent in the person of

Perdiccas

in 323 BC, and the territories were

divided between Alexander’s generals, who thereby became

satraps

, at the

Partition of Babylon

in 323 BC.

Rise of Seleucus

Coin of

Seleucus I Nicator

The Kingdoms of the

Diadochi

circa 303 BC

Alexander’s generals (the

Diadochi

) jostled for supremacy over parts of

his empire.

Ptolemy

, a former general and the satrap of

Egypt

, was the first to challenge the new

system; this led to the demise of Perdiccas. Ptolemy’s revolt led to a new

subdivision of the empire with the

Partition of Triparadisus

in 320 BC.

Seleucus

, who had been “Commander-in-Chief of

the camp” under Perdiccas since 323 BC but helped to assassinate him later,

received Babylonia

and, from that point, continued to

expand his dominions ruthlessly. Seleucus established himself in

Babylon

in 312 BC, the year used as the

foundation date of the Seleucid Empire. He ruled not only Babylonia, but the

entire enormous eastern part of Alexander’s empire:

“Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and

persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia,

‘Seleucid’ Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia,

Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by

Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire

were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region

from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.”

— Appian

, The Syrian Wars

Seleucus

went as far as

India

, where, after

two years of war

, he reached an agreement with

Chandragupta Maurya

, in which he exchanged his

eastern territories for a considerable force of 500

war elephants

, which would play a decisive role

at

Ipsus

(301 BC).

“The Indians occupy [in part] some of the countries situated along the

Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the

Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But

Seleucus Nicator

gave them to

Sandrocottus

in consequence of a marriage

contract, and received in return five hundred elephants.”

—Strabo, Geographica

Westward expansion

Following his and

Lysimachus

‘ victory over

Antigonus Monophthalmus

at the decisive

Battle of Ipsus

in 301 BC, Seleucus took

control over eastern

Anatolia

and northern

Syria

.

In the latter area, he founded a new capital at

Antioch on the Orontes

, a city he named after

his father. An alternative capital was established at

Seleucia on the Tigris

, north of Babylon.

Seleucus’s empire reached its greatest extent following his defeat of his

erstwhile ally, Lysimachus, at

Corupedion

in 281 BC, after which Seleucus

expanded his control to encompass western Anatolia. He hoped further to take

control of Lysimachus’s lands in Europe – primarily

Thrace

and even

Macedonia

itself, but was assassinated by

Ptolemy Ceraunus

on landing in Europe.

His son and successor,

Antiochus I Soter

, was left with an enormous

realm consisting of nearly all of the Asian portions of the Empire, but faced

with

Antigonus II Gonatas

in Macedonia and

Ptolemy II Philadelphus

in

Egypt

, he proved unable to pick up where his

father had left off in conquering the European portions of Alexander’s empire.

An overextended domain

Nevertheless, even before Seleucus’ death, it was difficult to assert control

over the vast eastern domains of the Seleucids. Seleucus invaded

Punjab region

region of

India

in 305 BC,

confronting

Chandragupta Maurya

(Sandrokottos),

founder of the

Maurya empire

. It is said that Chandragupta

fielded an army of 600,000 men and 9,000 war elephants (Pliny, Natural

History VI, 22.4).

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory,

sealed in a treaty, west of the Indus, including the

Hindu Kush

, modern day

Afghanistan

, and the

Balochistan

province of

Pakistan

. Archaeologically, concrete

indications of Mauryan rule, such as the inscriptions of the

Edicts of Ashoka

, are known as far as

Kandahar

in southern Afghanistan.

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married

Seleucus’s

daughter, or a

Macedonian

princess

, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an

alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500

war–elephants,

a military asset which would play a decisive role at the

Battle of Ipsus

in 301 BC. In addition to this

treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador,

Megasthenes

, to Chandragupta, and later

Deimakos

to his son

Bindusara

, at the Mauryan court at

Pataliputra

(modern

Patna

in

Bihar state

). Megasthenes wrote detailed

descriptions of India and Chandragupta’s reign, which have been partly preserved

to us through

Diodorus Siculus

. Later

Ptolemy II Philadelphus

, the ruler of

Ptolemaic Egypt

and contemporary of

Ashoka the Great

, is also recorded by

Pliny the Elder

as having sent an ambassador

named

Dionysius

to the Mauryan court.

Other territories lost before Seleucus’ death were

Gedrosia

in the south-east of the Iranian

plateau, and, to the north of this,

Arachosia

on the west bank of the

Indus River

.

Antiochus I (reigned 281–261 BC) and his son and successor

Antiochus II Theos

(reigned 261–246 BC) were

faced with challenges in the west, including repeated wars with

Ptolemy II

and a

Celtic

invasion of Asia Minor — distracting

attention from holding the eastern portions of the Empire together. Towards the

end of Antiochus II’s reign, various provinces simultaneously asserted their

independence, such as

Bactria

under

Diodotus

,

Parthia

under

Arsaces

, and

Cappadocia

under

Ariarathes III

.

In Bactria

, the satrap

Diodotus

asserted independence to

form the

Greco-Bactrian kingdom

c.245 BC.

Diodotus

, governor for the

Bactrian

territory, asserted independence in

around 245 BC, although the exact date is far from certain, to form the

Greco-Bactrian

kingdom. This kingdom was

characterized by a rich

Hellenistic

culture, and was to continue its

domination of Bactria until around 125 BC, when it was overrun by the invasion

of northern nomads. One of the Greco-Bactrian kings,

Demetrius I of Bactria

, invaded India around

180 BC to form the

Greco-Indian

kingdom, lasting until around AD

20.

The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, named

Andragoras

, first claimed independence, in a

parallel to the secession of his Bactrian neighbour. Soon after however, a

Parthian tribal chief called

Arsaces

invaded the Parthian

territory around 238 BC to

form the

Arsacid Dynasty

— the starting point of the

powerful

Parthian Empire

.

By the time Antiochus II’s son

Seleucus II Callinicus

came to the throne

around 246 BC, the Seleucids seemed to be at a low ebb indeed. Seleucus II was

soon dramatically defeated in the

Third Syrian War

against

Ptolemy III of Egypt

and then had to fight a

civil war against his own brother

Antiochus Hierax

. Taking advantage of this

distraction, Bactria and Parthia seceded from the empire. In Asia Minor too, the

Seleucid dynasty seemed to be losing control — Gauls had fully established

themselves in Galatia

, semi-independent semi-Hellenized

kingdoms had sprung up in

Bithynia

,

Pontus

, and

Cappadocia

, and the city of

Pergamum

in the west was asserting its

independence under the

Attalid Dynasty

.

Revival

(223–191 BC)

Silver coin of

Antiochus III the Great

.

The Seleucid Empire in 200 BC (before expansion into

Anatolia

and

Greece

).

A revival would begin when Seleucus II’s younger son,

Antiochus III the Great

, took the throne in 223

BC. Although initially unsuccessful in the

Fourth Syrian War

against Egypt, which led to a

defeat at the

Battle of Raphia

(217 BC), Antiochus would

prove himself to be the greatest of the Seleucid rulers after Seleucus I

himself. He spent the next ten years on his

anabasis

through the eastern parts of his

domain and restoring rebellious vassals like Parthia and

Greco-Bactria

to at least nominal obedience. He

won the

Battle of the Arius

and

besieged the Bactrian capital

, and even

emulated Alexander with an expedition into India where he met with king

Sophagasenus

receiving war elephants:

“He (Antiochus) crossed the Caucasus and descended into India; renewed

his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more

elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more

provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving

Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king

had agreed to hand over to him”. Polybius 11.39

When he returned to the west in 205 BC, Antiochus found that with the death

of

Ptolemy IV

, the situation now looked propitious

for another western campaign. Antiochus and

Philip V of Macedon

then made a pact to divide

the Ptolemaic possessions outside of Egypt, and in the

Fifth Syrian War

, the Seleucids ousted

Ptolemy V

from control of

Coele-Syria

. The

Battle of Panium

(198 BC) definitively

transferred these holdings from the Ptolemies to the Seleucids. Antiochus

appeared, at the least, to have restored the Seleucid Kingdom to glory.

Expansion into Greece and War with Rome

Following his erstwhile ally

Philip’s

defeat by Rome in 197 BC, Antiochus

saw the opportunity for expansion into Greece itself. Encouraged by the exiled

Carthaginian

general

Hannibal

, and making an alliance with the

disgruntled

Aetolian League

, Antiochus launched an invasion

across the

Hellespont

. With his huge army he was intent

upon establishing the Seleucid empire as the foremost power in the Hellenic

world but these plans put the empire on a collision course with the new

superpower of the Mediterranean, the

Roman Republic

. At the battles of

Thermopylae

and

Magnesia

, Antiochus’s forces were resoundingly

defeated and he was compelled to make peace and sign the

Treaty of Apamea

in (188 BC), the main clause

of which saw the Seleucids agree to pay a large indemnity, retreat from

Anatolia

and to never again attempt to expand

Seleucid territory west of the

Taurus Mountains

. The

Kingdom of Pergamum

and the

Republic of Rhodes

, Rome’s allies in the war,

were given the former Seleucid lands in Anatolia. Antiochus died in 187 BC on

another expedition to the east, where he sought to extract money to pay the

indemnity.

Roman power,

Parthia and Judea

The reign of his son and successor

Seleucus IV Philopator

(187-175 BC) was largely

spent in attempts to pay the large indemnity, and Seleucus was ultimately

assassinated by his minister

Heliodorus

.

Seleucus’ younger brother,

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

, now seized the throne.

He attempted to restore Seleucid power and prestige with a successful war

against the old enemy,

Ptolemaic Egypt

, which met with initial success

as the Seleucids defeated and drove the Egyptian army back to

Alexandria

itself. As the king planned on how

to conclude the war, he was informed that Roman commissioners, led by the

Proconsul

Gaius Popillius Laenas

, were near and

requesting a meeting with the Seleucid king. Antiochus agreed, but when they met

and Antiochus held out his hand in friendship, Popilius placed in his hand the

tablets on which was written the decree of the senate and telling him to read

it. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider

what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king’s feet

with the stick he was carrying and said, “Before you step out of that circle

give me a reply to lay before the senate.” For a few moments he hesitated,

astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, “I will do what the

senate thinks right.” He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to

war with Rome again.

The latter part of his reign saw a further disintegration of the Empire

despite his best efforts. Weakened economically, militarily and by loss of

prestige, the Empire became vulnerable to rebels in the eastern areas of the

empire, who began to further undermine the empire while the Parthians moved into

the power vacuum to take over the old Persian lands. Antiochus’ aggressive

Hellenizing (or de-Judaizing) activities provoked a full scale armed rebellion

in Judea

—the

Maccabean Revolt

. Efforts to deal with both the

Parthians and the Jews as well as retain control of the provinces at the same

time proved beyond the weakened empire’s power. Antiochus died during a military

expedition against the Parthians in 164 BC.

Civil war and

further decay

Coin of

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

.

Silver coin of

Alexander Balas

.

After the death of

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

, the Seleucid Empire

became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous

at best. Epiphanes’ young son,

Antiochus V Eupator

, was first overthrown by

Seleucus IV’s son,

Demetrius I Soter

in 161 BC. Demetrius I

attempted to restore Seleucid power in

Judea

particularly, but was overthrown in 150

BC by

Alexander Balas

— an impostor who (with

Egyptian backing) claimed to be the son of Epiphanes. Alexander Balas reigned

until 145 BC, when he was overthrown by Demetrius I’s son,

Demetrius II Nicator

. Demetrius II proved

unable to control the whole of the kingdom, however. While he ruled

Babylonia

and eastern

Syria

from

Damascus

, the remnants of Balas’ supporters —

first supporting Balas’ son

Antiochus VI

, then the usurping general

Diodotus Tryphon

— held out in

Antioch

.

Meanwhile, the decay of the Empire’s territorial possessions continued apace.

By 143 BC, the

Jews

in form of the

Maccabees

had fully established their

independence.

Parthian

expansion continued as well. In 139

BC, Demetrius II was defeated in battle by the Parthians and was captured. By

this time, the entire Iranian Plateau had been lost to Parthian control.

Demetrius Nicator’s brother,

Antiochus VII Sidetes

, took the throne after

his brother’s capture. He faced the enormous task of restoring a rapidly

crumbling empire; one facing threats on multiple fronts. Hard-won control of

Coele-Syria

was threatened by the Jewish

Maccabee rebels. Once-vassal dynasties in Armenia, Cappadocia, and Pontus were

threatening Syria and northern

Mesopotamia

; the nomadic Parthians, brilliantly

led by

Mithridates I of Parthia

had overrun uppland

Media (home of the famed

Nisean horse

herd); and Roman intervention was

an ever-present threat. Sidetes managed to bring the Maccabees to heel; frighten

the Anatolian dynasts into a temporary submission; and then, in 133, turned east

with the full might of the Royal Army (supported by a body of Jews under the

Maccabee prince, John Hyrcanus) to drive back the Parthians.

Sidetes’ campaign initially met with spectacular success, recapturing

Mesopotamia, Babylonia and Media; defeating and slaying the Parthian Satrap of

Seleucia-on-Tigris

in personal combat. In the

winter of 130/129 BC, his army was scattered in winter quarters throughout Media

and Persis when the Parthian king,

Phraates II

, counter-attacked. Moving to

intercept the Parthians with only the troops at his immediate disposal, he was

ambushed and killed. Antiochus Sidetes is sometimes called the last great

Seleucid king.

After the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes, all of the recovered eastern

territories were recaptured by the Parthians. The Maccabees again rebelled,

civil war soon tore the empire to pieces, and the Armenians began to encroach on

Syria from the north.

Collapse

(100–63 BC)

By 100 BC, the once formidable Seleucid Empire encompassed little more than

Antioch

and some Syrian cities. Despite the

clear collapse of their power, and the decline of their kingdom around them,

nobles continued to play kingmakers on a regular basis, with occasional

intervention from

Ptolemaic Egypt

and other outside powers. The

Seleucids existed solely because no other nation wished to absorb them — seeing

as they constituted a useful buffer between their other neighbours. In the wars

in Anatolia between

Mithridates VI

of

Pontus

and

Sulla

of Rome, the Seleucids were largely left

alone by both major combatants.

Mithridates’ ambitious son-in-law,

Tigranes the Great

, king of

Armenia

, however, saw opportunity for expansion

in the constant civil strife to the south. In 83 BC, at the invitation of one of

the factions in the interminable civil wars, he invaded Syria, and soon

established himself as ruler of Syria, putting the Seleucid Empire virtually at

an end.

Seleucid rule was not entirely over, however. Following the Roman general

Lucullus

‘ defeat of both Mithridates and

Tigranes in 69 BC, a rump Seleucid kingdom was restored under

Antiochus XIII

. Even so, civil wars could not

be prevented, as another Seleucid,

Philip II

, contested rule with Antiochus. After

the Roman conquest of Pontus, the Romans became increasingly alarmed at the

constant source of instability in Syria under the Seleucids. Once Mithridates

was defeated by Pompey

in 63 BC, Pompey set about the task of

remaking the Hellenistic East, by creating new client kingdoms and establishing

provinces. While client nations like

Armenia

and

Judea

were allowed to continue with some degree

of autonomy under local kings, Pompey saw the Seleucids as too troublesome to

continue; and doing away with both rival Seleucid princes, he made Syria into a

Roman province.

Culture

Bagadates I

(Minted 290–280 BC) was

the first indigenous Seleucid satrap to be appointed.

The Seleucid empire’s geographic span, from the

Aegean Sea

to what is now

Afghanistan

and

Pakistan

, created a melting pot of various

peoples, such as Greeks

,

Armenians

,

Persians

,

Medes

,

Assyrians

, and

Jews

. The immense size of the empire, followed

by its encompassing nature, made the Seleucid rulers have a governing interest

in implementing a policy of racial unity initiated by Alexander.

The

Hellenization

of the Seleucid empire was

achieved by the establishment of Greek cities throughout the empire.

Historically significant towns and cities, such as

Antioch

, were created or renamed with more

appropriate

Greek

names. The creation of new

Greek

cities and towns was aided by the fact

that the Greek mainland was overpopulated and therefore made the vast Seleucid

empire ripe for colonization. Colonization was used to further Greek interest

while facilitating the assimilation of many native groups. Socially, this led to

the adoption of Greek practices and customs by the educated native classes in

order to further themselves in public life and the ruling

Macedonian

class gradually adopted some of the

local traditions. By 313 BC, Hellenic ideas had begun their almost 250-year

expansion into the Near East, Middle East, and Central Asian cultures. It was

the empire’s governmental framework to rule by establishing hundreds of cities

for trade and occupational purposes. Many of the existing cities began — or were

compelled by force — to adopt Hellenized philosophic thought, religious

sentiments, and politics.

Synthesizing Hellenic and indigenous cultural, religious, and philosophical

ideas met with varying degrees of success — resulting in times of simultaneous

peace and rebellion in various parts of the empire. Such was the case with the

Jewish population of the Seleucid empire because the Jews posed a significant

problem which eventually led to war. Contrary to the accepting nature of the

Ptolemaic

empire towards native religions and

customs, the Seleucids gradually tried to force Hellenization upon the Jewish

people in their territory by outlawing Judaism. This eventually led to the

revolt of the Jews

under Seleucid control,

which would later lead to the Jews achieving independence.

Seleucid rulers

Seleucus I Nicator

, the founder of

the Seleucid Empire.

The Seleucid dynasty or the Seleucidae (from

Greek

: Σελευκίδαι,

Seleukídai) was a

Greek

Macedonian

descendants of

Seleucus I Nicator

(“the Victor”), who ruled

the

Seleucid Kingdom

centered in the

Near East

and regions of the

Asian part of the earlier

Achaemenid

Persian Empire

during the

Hellenistic period

.

List

Seleucid Rulers

| King |

Reign (BCE) |

Consort(s) |

Comments |

|

Seleucus I Nicator

|

Satrap

311-305

King 305-281 |

Apama

|

|

|

Antiochus I Soter

|

co-ruler from 291, ruled 281-261 |

Stratonice of Syria

|

Co-ruler with his father for 10 years |

|

Antiochus II Theos

|

261-246 |

Laodice I

Berenice

|

Berenice was a daughter of

Ptolemy II

of Egypt. Laodice I had her

and her son murdered. |

|

Seleucus II Callinicus

|

246-225 |

Laodice II

|

|

Seleucus III Ceraunus

(or Soter) |

225-223 |

|

Seleucus III was assassinated by members of his army. |

|

Antiochus III the Great

|

223-187 |

Laodice III

Euboea of Chalcis |

Antiochus III was a brother of Seleucus III |

|

Seleucus IV Philopator

|

187-175 |

Laodice IV

|

This was a brother-sister marriage. |

|

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

|

175-163 |

Laodice IV

|

|

|

Antiochus V Eupator

|

163-161 |

|

|

|

Demetrius I Soter

|

161-150 |

Apama ?

Laodice V

? |

Son of Seleucus IV Philopator and Laodice IV |

|

Alexander I Balas

|

150-145 |

Cleopatra Thea

|

Son of Antiochus IV and

Laodice IV

|

|

Demetrius II Nicator

|

first reign, 145-138 |

Cleopatra Thea

|

Son of Demetrius I |

Antiochus VI Dionysus

(or Epiphanes) |

145-140? |

|

Son of Alexander Balas and Cleopatra Thea |

|

Diodotus Tryphon

|

140-138 |

|

General who was a regent for Antiochus VI Dionysus. Took the throne

after murdering his charge. |

Antiochus VII Sidetes

(or Euergetes) |

138-129 |

Cleopatra Thea

|

Son of Demetrius I |

|

Demetrius II Nicator

|

second reign, 129-126 |

Cleopatra Thea

|

Demetrius was murdered at the instigation of his wife Cleopatra

Thea. |

|

Alexander II Zabinas

|

129-123 |

|

Counter-king who claimed to be an adoptive son of Antiochus VII

Sidetes |

|

Cleopatra Thea

|

126-123 |

|

Daughter of Ptolemy VI of Egypt. Married to three kings: Alexander

Balas, Demetrius II Nicator, and Antiochus VII Sidetes. Mother of

Antiochus VI, Seleucus V, Antiochus VIII Grypus, and Antiochus IX

Cyzicenus. Coregent with her son Antiochus VIII Grypus. |

|

Seleucus V Philometor

|

126/125 |

|

Murdered by his mother Cleopatra Thea |

|

Antiochus VIII Grypus

|

125-96 |

Tryphaena

of Egypt

Cleopatra Selene I

of Egypt |

|

|

Antiochus IX Cyzicenus

|

114-96 |

Cleopatra IV of Egypt

Cleopatra Selene I

of Egypt |

|

Seleucus VI Epiphanes

Nicator |

96-95 |

|

|

Antiochus X Eusebes

Philopator |

95-92 or 83 |

Cleopatra Selene I

|

|

Demetrius III Eucaerus

(or Philopator) |

95-87 |

|

|

Antiochus XI Epiphanes

Philadelphus |

95-92 |

|

|

|

Philip I Philadelphus

|

95-84/83 |

|

|

|

Antiochus XII Dionysus

|

87-84 |

|

|

(Tigranes

I of Armenia) |

83-69 |

|

|

Seleucus VII Kybiosaktes

or Philometor |

83-69 |

|

|

|

Antiochus XIII Asiaticus

|

69-64 |

|

|

|

Philip II Philoromaeus

|

65-63 |

|

|

Family tree

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Antiochus |

|

Laodice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seleucus I Nicator

Kg. 305–281 |

|

Apama

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Achaeus |

|

|

Stratonice

|

|

Antiochus I Soter

Kg. 281–261 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Andromachus

|

|

|

|

|

Antiochus II Theos

Kg. 261–246 |

|

Laodice I

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Achaeus

Kg. 220–213 |

|

|

Laodice II

|

|

Seleucus II Callinicus

Kg. 246–226 |

|

Antiochus Hierax

Kg. 240–228 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seleucus III Ceraunus

Kg. 226–223 |

|

Antiochus III the Great

Kg. 223–187 |

|

Laodice III

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seleucus IV Philopator

Kg. 187–175 |

|

Laodice |

|

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Kg. 175–163 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Apama |

|

Demetrius I Soter

Kg. 161–150 |

|

Antiochus V Eupator

Kg. 163–161 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexander I Balas

Kg. 150–146 |

|

Cleopatra Thea

|

|

Demetrius II Nicator

Kg. 145–125 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Antiochus VII Sidetes

Kg. 138–129 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Antiochus VI Dionysus

Kg. 144–142 |

|

Seleucus V Philometor

Kg. 126–125 |

|

Antiochus VIII Grypus

Kg. 125–96 |

|

Cleopatra |

|

|

|

Antiochus IX Cyzicenus

Kg. 116–96 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seleucus VI Epiphanes

Kg. 96–95 |

|

Antiochus XI Epiphanes

Kg. 95–92 |

|

Philip I Philadelphus

Kg. 95–83 |

|

Demetrius III Eucaerus

Kg. 95–88 |

|

Antiochus XII Dionysus

Kg. 87–84 |

|

Antiochus X Eusebes

Kg. 95–83 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philip II Philoromaeus

Kg. 69–63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Antiochus XIII Asiaticus

Kg. 69–64 |

|

![Q1 [st] st](https://i0.wp.com/bits.wikimedia.org/static-1.22wmf3/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_Q1.png?w=1200&ssl=1)

![X1 [t] t](https://i0.wp.com/bits.wikimedia.org/static-1.22wmf3/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png?w=1200&ssl=1)

![Z4 [y] y](https://i0.wp.com/bits.wikimedia.org/static-1.22wmf3/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_Z4.png?w=1200&ssl=1)

![Eros1st c. BCE marble from Pompeii. This statue is also known as Eros Centocelle, and is thought to be a copy of the colossal Eros of Thespiae, a work by Praxiteles.[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/Eros_Farnese_MAN_Napoli_6353.jpg/150px-Eros_Farnese_MAN_Napoli_6353.jpg) herios,

herios,